Preprint

Article

Cape Verde: Islands of Vulnerability or Resilience? A Transition from a MIRAB Model into a TOURAB One?

Altmetrics

Downloads

78

Views

35

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

11 December 2023

Posted:

12 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Small island developing states (SIDS) traditionally face a set of challenges like the narrow economic structure, environmental issues, and dependence on a few ranges of economic activities forcing them to open the economy to the exterior. Therefore, their development model, like in Cape Verde depends on migration, remittances, dependence on aid, tourism, and state employment. The current research offers an insight about the nature of Cape Verde’s economy as a SIDS and the degree to which its economy depends on tourism and government services, both of which are supported through aid programs. Understanding Cape Verde’s development model is important to clarify the challenges the country faces, and its development needs to gather a long-term resilience and to understand if it is changing from a MIRAB (Migrations, Remittances, Aid and Bureaucracy) model into another one.

Keywords:

Subject: Business, Economics and Management - Economics

Introduction

Nowadays we find everywhere some widely recognised low-lying, islandness, undiversified island countries, traditionally named as SIDS (small island developing states) [1,2,3].

These countries not only face the above vulnerabilities but have also been forced rely on both international aid and financial remittances from citizens working abroad, tourism flows. Within this context, several countries have been diversifying their development strategies and development models as we will see later in literature review section [1,4,5,6].

The small Atlantic Island State of Cape Verde is the focus of this research. Cape Verde, like many several other SIDS has long been reliant on both international aid, foreign direct investment, remittances, and tourism to broaden its economic basis and to its economic well-being [4,7]. In light of this, this research will analyse which flows have been growing and if it can be characterized on the MIRAB or TOURAB (tourism, aid and bureaucracy) states [1,8].

There has been a lack of basic research in the SIDS context, particularly when it creates specific bridge design standards for most SIDS countries. This situation may cause the application of multiple interpretations from different funders and consultants. This is not a desirable situation for these countries.

This research tries to analyse Cape Verde and its potential change of classification from a MIRAB model to a TOURAB (tourism, aid and bureaucracy) or SITE (small island tourism economy) model reflecting the changing nature of national economy and its taxonomy. This raises the question, how long is Cape Verde going to stay in a MIRAB model or change into a different model and also which have been the major development determinants in these last years?

Cape Verde has consistently relied upon migrations, aid and bureaucracy, but in the last years tourism has been gaining some predominance and contributed to the economic growth and consistent job opportunities. Compared to other SIDS, tourism is a new born activity. Although, it is becoming very significant.

As a microstate Cape Verde may be understood as a SITE country since it meets some of the characteristics outlined by McElroy and Parry [9]. Cape Verde has already experienced some of the SITE’s challenges such as tourism repatriation of profits, increased crime and land degradation.

The paper is structured as follows. First, a brief synopsis of the existing literature about the specific nature, dynamics and vulnerabilities of SIDS is examined. Next, the methodology is explained. Third, this section examines the importance of the various variables of the MIRAB model in Cape Verde. Finally, the conclusion highlights the major challenges of this country.

Literature Review

Several small island states, like Cape Verde have long been adopted a MIRAB (Migrations, Remittances, Aid and Bureaucracy) model that allows them to be resilient in the use of the scarce resources, showing a strong capacity to reinvent themselves according to their market opportunities [10].

In order to better understand the development challenges and opportunities which SIDS face, it is important to reflect how development strategies in island states have been understood.

Small island developing states have many similarities like social, economic and environmental challenges and vulnerabilities [8].

Some main aspects of island geographies have been presented by Baldacchino [11], Kelman [12], Grydehøj and Lewis [14]: (i) being bordered or bounded with clearly demarcated land-based spatial limits; (ii) being small in terms of land area, population, resources and livelihood opportunities; (iii) distance, marginalisation, isolation or separation from other land areas, peoples and communities; (iv) littorality, as a consequence of land–water interactions, coastal zones and intersections of archipelagos. It brings additional opportunities through resources for fishing, tourism and trade [15].

The MIRAB model was firstly created to conceptualise the economies of SIDS that were dependent on international support and remittances from emigrated family members [4,16,17].

This “multiple migration process” (p. 68) create remittances that have long been used to support family members, a way to save for their future on the island and to invest. These remittances help to build a “life-long commitment” while foreign aid supports bureaucracy, creates local employment in the public sector, infrastructure development, education, health [16]. All these flows may improve the quality of life and human capital of MIRAB states.

However, this model has several aspects that need to be taken care.

Those SIDS whose receipts depend on the service sector (travel and tourism) are often dominated by multi-national corporations (MNCs) that redirect most of their profits away from the destination [8,20].

It is important to notice that if skills are not enough developed or if diversity is not fully supported, dependence on a single industry, or investment into infrastructure without local returns may cause vulnerability as it has been demonstrated for the island tourism industry alongside solutions for using a tourism focus to overcome island vulnerability [21].

SIDS tend to have low diversification in exported goods and in trade commodities or raw materials being particularly susceptible to changes in demand and prices [2]. Another vector is the high outward migration that creates an important diasporic economy of SIDS [8,16].

The migration, remittances, aid and bureaucracy model (MIRAB) has been a focus from researchers [4,16,22,23].

Most SIDS also face vulnerabilities or challenges as a consequence of poor road systems that limits the transport network [24], international transport limitations [25], exposure to the effects of adverse climate events [26], climate effects in coastal infrastructure and even the lack of economic diversification associated to the COVID-19 post-pandemic that may conduct to extreme poverty almost 169 million people in these countries [28].

All the above vulnerabilities exacerbate the path of development within Small Island States due to their geographical and socio-economic constraints even though they are often considered as some of the most beautiful places in the world [28]. However, these economies also share an opportunity for innovation providing a leverage on digital technologies and other assets such as data [28].

International literature has long focused on the impact of good governance on national economies believing that if properly managed, this can promote new development paths (e.g., [30,31,32]. Saha et al. associated institutional development with mature democracy. Fosu concluded that long-run growth is reduced by political instability. Alesina and Perotti concluded that weak institutions reduced growth through their negative impact on investment.

Congdon Fors stated that country size is negatively related to institutional quality.

Regardless all the above approaches, historical discussion about development issues of SIDS, have stated that the core of the hardships of these countries are a consequence of their weak economic potential dictated by narrow resource base and small populations [38].

The vulnerability to forces outside their control which sometimes threatens their economic viability is another issue [39].

Alesina and Wacziarg stated that smaller countries have larger public sectors and are more open to trade increasing their exposure and making them more susceptible to external shocks.

Bertram states that the combination of a large government sector and a limited productive base, in many cases a consequence of their former post-colonial small state situation may turn them reliant upon state employment and aid funding.

Armstrong et al. demonstrated that the most successful microstates were associated with a rich exportable resource base as well as a successful tourism and business/financial services.

All the prior findings confirm that exports, international flows and governance are extremely important SIDS economic performance and growth. Besides, physical and human capital, FDI, private investment, and policy environment are also important sources of growth [38].

Several models have appeared to analyse the economic issues of SIDS. Another model that encompasses tourism, aid and bureaucracy was proposed by Guthunz and von Krosigk (in Tisdell [42]; and Apostolopoulos and Gayle (p. 10). They have explored the ‘transformation of MIRAB societies to TOURAB (tourism, aid, bureaucracy) economies. The TOURAB model, that is not in widespread use suggests that these economies are primarily dependent on tourism and aid distribution through the bureaucracy [42]. Although the TOURAB model is less established than the MIRAB or SITE model, it is believed that this model is the precursor of the SITE (small island tourism economy) model also used to describe many SIDS whose economies experienced a significant growth of tourism flows and receipts.

Niue is an example of a transition from a MIRAB model to a TOURAB model reflecting the major changes of the national economy and its taxonomy [44].

SITEs are usually more affluent than MIRAB states [45], even though affiliated MIRAB states may use migration process to support their tourism industry [8,45,46].

The most economically advanced SITEs (most of which are Caribbean islands such as Aruba, Bermuda and the US Virgin Islands) are wealthier and depend on a larger immigrant society in urban areas to meet the tourism labour demands [9].

However, McElroy and Parry highlighted the challenge of an adequate infrastructure for some SITEs in order to fully take advantage of this activity. To achieve this, it is important to deal with the negative externalities of those economies dominated by tourism such as pollution, environmental degradation on land and on reefs, impacts on local culture, increased crime rates and price hikes in property [9].

Overview of Cape Verde

Cape Verde islands were discovered by Portuguese seafarers in the 15th century. Santiago was the first island to be settled, and São Vicente was the last. Due to its climate conditions, this country has long suffered from the Sahelian aridity and extremely unfavourable climate, making food production a perennial humanitarian and administrative challenge [19,47]. Initially, the most significant economic activity of Cape Verde was providing an entrepôt for transcontinental slave trade which brought the miscegenation process between white Europeans and black Africans, the historical basis of the formation of a creole population [19]. Through its history, Cape Verde faced numerous droughts and famines and witnessed the emigration as a way to avoid being poor. This has long created a globalised and diasporic nation.

This has provided Cape Verdean population with a flexible culture and identity, located between various worlds and between various civilizations [48].

Cape Verde is a small archipelago of ten islands located in the North Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Africa. Due to its climate conditions, this country has long suffered from the Sahelian aridity and extremely unfavorable climate, making food production a perennial humanitarian and administrative challenge [19].

Cabo Verde has been highly susceptible to the effects of climate change, as evidenced by the recent four-year drought. The government is rightly focusing on implementation of climate adaptation and mitigation measures in their most recent 5-year development strategy (PEDS II) [49].

Only 10 percent of the land is arable, and the country is heavily dependent on food imports – over 80 percent of the food must be imported. Cape Verde’s economy become service oriented mainly due to tourism, which accounts for over 65 percent of GDP [19].

Although nearly 70 percent of the population lives in rural areas, agriculture and fishing account for only about 10 percent of GDP, and light manufacturing accounts for about 20 percent of GDP, including food and fish processing, shoes and garments, salt mining, and ship repair. Cape Verde’s economic and policy performance has strengthened significantly in recent years, supported by reforms pursued under the International Monetary Fund-sponsored PRGF (Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility) arrangement, and more recently the PSI (Policy Support Instrument) program [50].

It is also important to refer one other particularity of Cape Verde. The sea associated with the condition of insularity has always been seen as a constitutive part of the identity of Cape Verdeans. As a matter of a fact, this identity has been described and analysed first and foremost through its islandness (Giufrrè, 2021). The difficulties of survival in a country with limited natural resources have historically induced many Cape Verdeans to emigrate. Nowadays, we find more than one million people of Cape Verdean ancestry in the world. Some 500,000 people of Cape Verdean ancestry live in the United States, mainly in New England. Portugal, Netherlands, Italy, France and Senegal also have large communities. This diaspora has significantly influenced the culture and the economy of Cape Verde [50].

Cape Verde's experience shows that the effectiveness of aid, together with foreign investment, remittances from emigrants and, more recently, tourism revenues, together with good governance [51], have contributed to the strong capitalization and growth of the Cape Verdean economy.

Good governance can be understood in three ways: (i) good governance is identified with democratic quality, i.e. fundamental civil rights, legal certainty and the protection of basic socio-economic rights; (ii) the second translates mainly into the adoption of good policies, i.e. fiscal balance, monetary restraint, trade liberalization and free flow of capital, investment incentives, etc. and (iii) good governance is associated with strong institutions [52].

Cape Verde has experienced a strong, balanced, sustainable, and inclusive economic growth over the last twenty-five years, with the exception of the severe contraction in 2020 as a result of COVID-19. This period, which began in the 1990s with the transition to a parliamentary democracy and the deepening of the market economy, is the result of decisions taken two decades before independence began in 1975, with the creation of a basic consensus among the ruling elite, based on the promotion of a market economy and the creation of a cohesive and inclusive society and a strong commitment to the fight against poverty.

Cape Verde enjoys one of sub-Saharan Africa's most consolidated democratic systems and over time political parties have been acting as institutions vying for power as opposed to mechanism for the propagation of political patronage or self-serving elites. In the last decades, it has become clear that economic challenges will continue to be the greatest political issue for years to come This situation is reflected in two different situations: (i) the Political Risk Index that measures the level of risk posed to governments, corporations, and investors, whose scores assigned from 0-10 (a score of 0 marks the highest political risk, while a score of 10 marks the lowest political risk) Cape Verde achieved a 6 and (ii) the Political Stability Index measuring a country's level of stability, standard of good governance, record of constitutional order, respect for human rights, and overall strength of democracy. The Political Stability Index is based on a given country's record of peaceful transitions of power, ability of a government to stay in office and carry out its policies vis a vis risk credible risks of government collapse. In other words, this index measures the dynamic between the quality of a country's government and the threats that can compromise and undermine stability. Final score was a 6 where a score of 0 marks the lowest level of political stability and an ultimate nadir, while a score of 10 marks the highest level of political stability possible [53].

The GDP of the Cape Verdean economy has been growing at a remarkable average annual rate of 6.9% in the period 1991-2015, which represents a growth rate of 1,5%. Cabo Verde was hit hard by the effects of COVID-19 and the impact of the war in Ukraine and this situation was reflected in GDP’s drop by 14,8% in 2020. However, the economy rebounded strongly in 2022 growing 17,7 percent, mainly supported by the recovery of tourism sector. The 2023 budget appears on track and is aligned with the ECF-supported program. The Banco de Cabo Verde (BCV) has started to tighten monetary policy settings to narrow the interest rate differential with the European Central Bank (ECB) and protect the peg [49].

Real GDP is projected to grow by 5,7 percent in 2023 and 6,2 percent in 2024, mainly supported by agriculture, energy, the digital economy, and tourism. However, the country is much open to external events such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rising global interest rates, climate change, and potential recession in Europe, which accounts for 80% of imports. Inflation rate is projected to remain high, at 7,8 percent in 2023 and 6,5 percent in 2024, driven by imported food and energy prices. The fiscal deficit is projected to narrow from 4,5 percent of GDP in 2023 to 3,5 percent in 2024, as a result of the improved tax collection. The current account deficit is projected to shrink to 5,4 percent of GDP in 2024 from 7,0 percent in 2023, as a consequence of the recovery in tourism and remittances. Altogether, both may contribute to preserve international reserves at 5,5 months of import cover. The poverty rate is projected to fall to 34 percent in 2023 with the progressive resumption of economic growth [54].

The most remarkable thing about this situation is that its growth has always occurred in a context of serious scarcity of conventional natural resources (water, land, hydrocarbons and other minerals). In this context, it is worth highlighting the efforts of successive governments to implement relatively advanced policies in areas such as the use of renewable energy sources, desalination of seawater to supply the local population and tourists. Naturally, there are also challenges linked to the proper treatment of wastewater and the recycling of urban waste, which makes up the vast majority of the country's solid waste.

In any case, we can point out that Cape Verde's inclusive economic growth has been driven by intense investment efforts to increase physical, human, environmental, social and technological capital. This effort stems from the main sources of external funding, namely foreign direct investment, emigrants' remittances, development aid and, more recently, tourism revenues [50].

This management of budget support has led to the creation of a framework for collaboration between the national government and experts from donor countries, which has improved the country's strategic planning, making it more effective and reliable.

This budget support has enabled the modernization of the tax system and budget management, making it more effective and accountable.

Finally, it should be noted that the targeting of the various aid flows has been crucial to sustaining the social inclusion and poverty alleviation policies that are fundamental to the legitimacy and social stability achieved by the country over the years [53].

Methodology

Here is intended to analyse, according to the presented models, how, Remittances of Emigrants (RE), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Public development Aid (PDA) and Tourism receipts (TR) have the potential to contribute to Gross domestic product (GDP) development. These were the most important variables towards a development path.

Variable data were taken from several sources, such as the World Bank (WB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the National Institute of Statistics of Cape Verde (NIS), and the variables were observed from 2000 to 2021.

This research is based on a quantitative approach based on a time series statistics that were produced over time and is restricted to what can be observed and measured. Quantitatively, the research aims to determine the most important factors influencing GDP flows to Cape Verde and test formulated hypotheses based on prior theoretical and empirical studies.

Descriptive Statistics and Graphical analysis

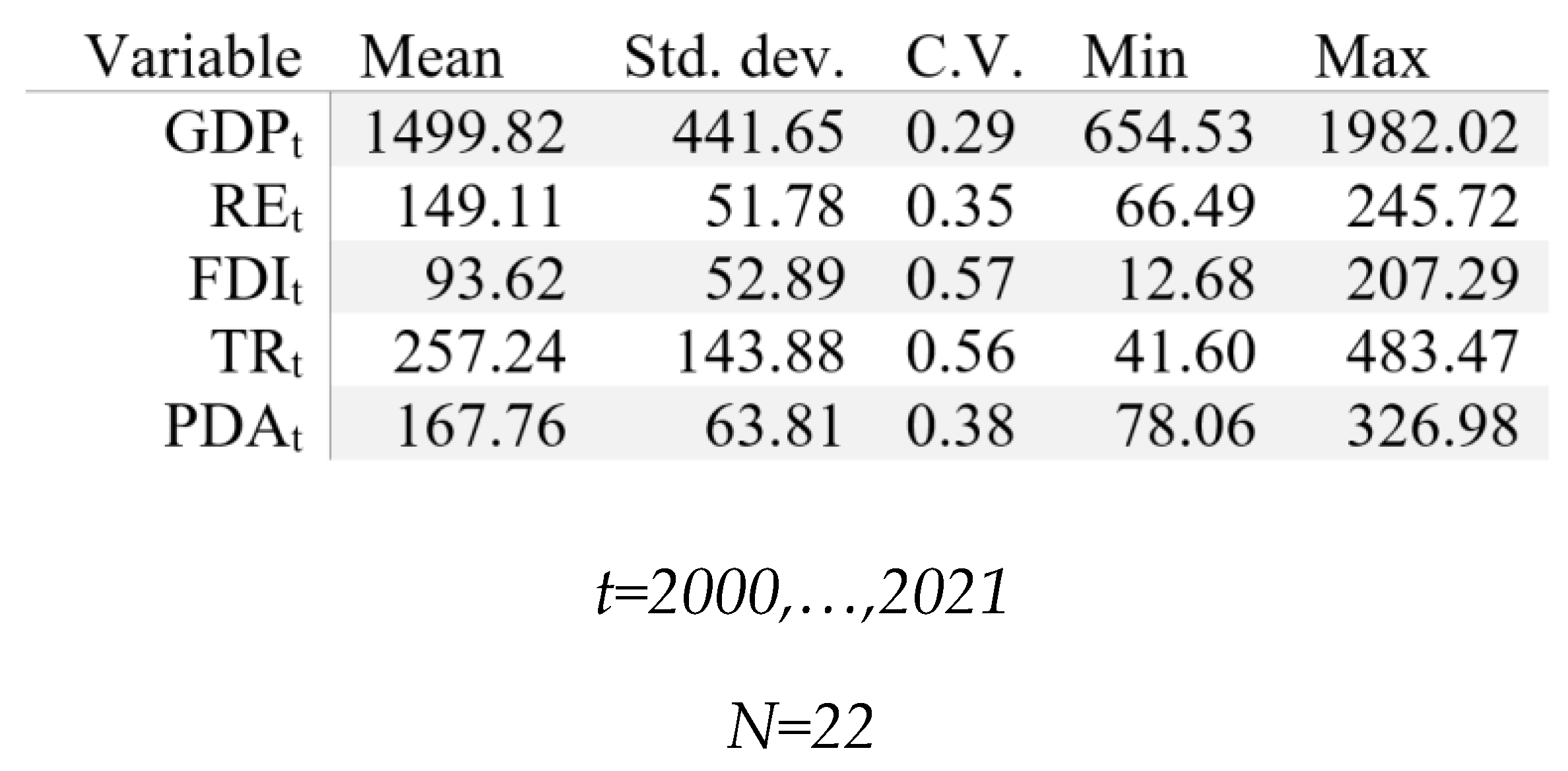

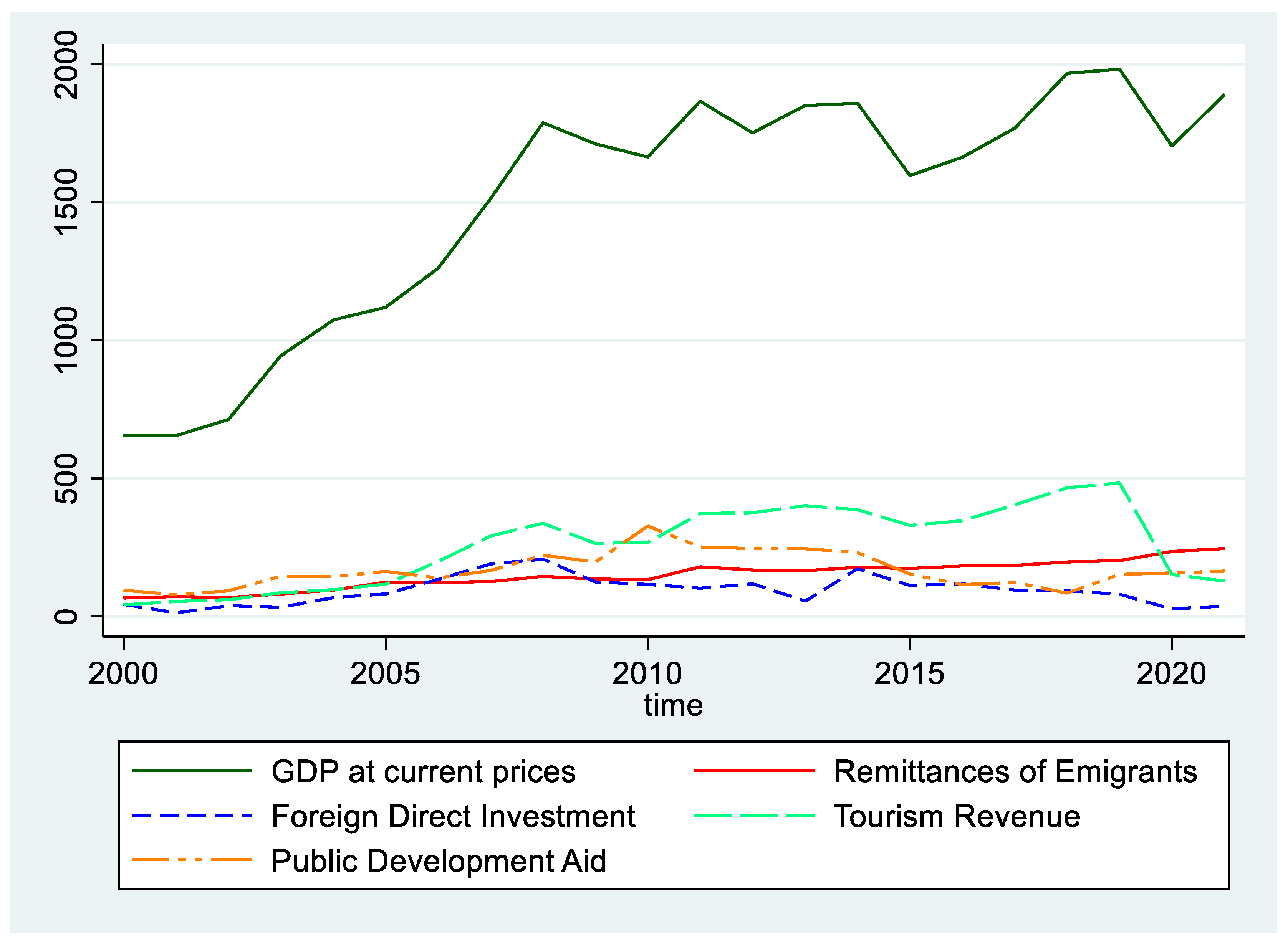

Figure 1.

Descriptive Statistics. Source: The authors.

It can be observed that the variables with higher variation across the years are FDI and Tourism receipts, but also Remittance of Emigrants and Public development Aid, have values of variation coefficient greater than 0.3 (30%) [17].

Figure 2.

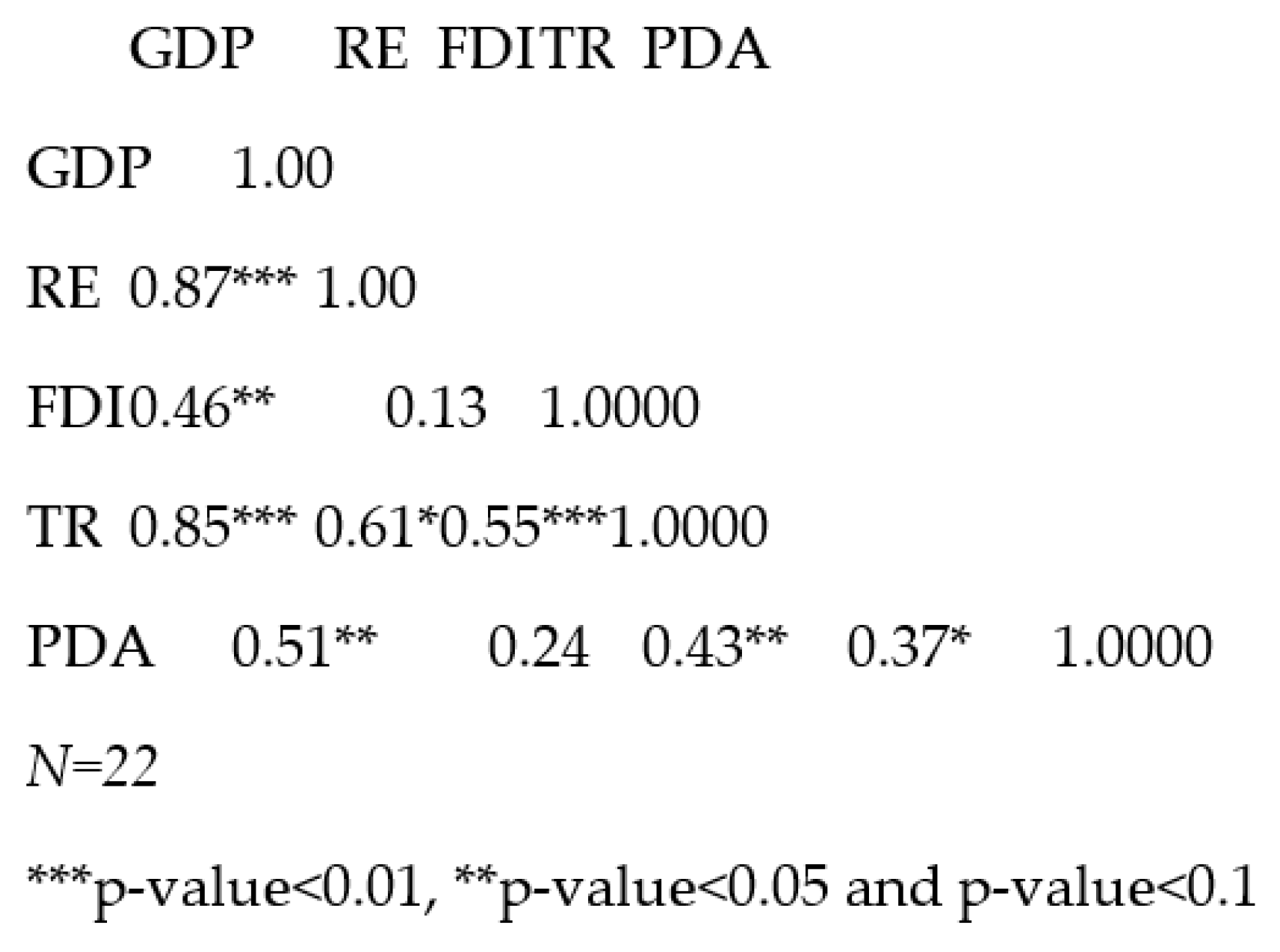

Correlation Matrix between the indicators in study. Source: The authors.

The correlations are not statically significant between RE and FDI and between RE and PDA, the higher correlation is between GDP and RE, also, one can observe, in decreasing order of correlation, with GDP are respectively RE, TR, PDA and FDI.

At Figure 3 it can be observed the tourism revenue has increased until 2019 and decreased in 2020 (the pandemic year), also it can be observed a decrease on FDI and GDP in the same year and slight increase in 2021.

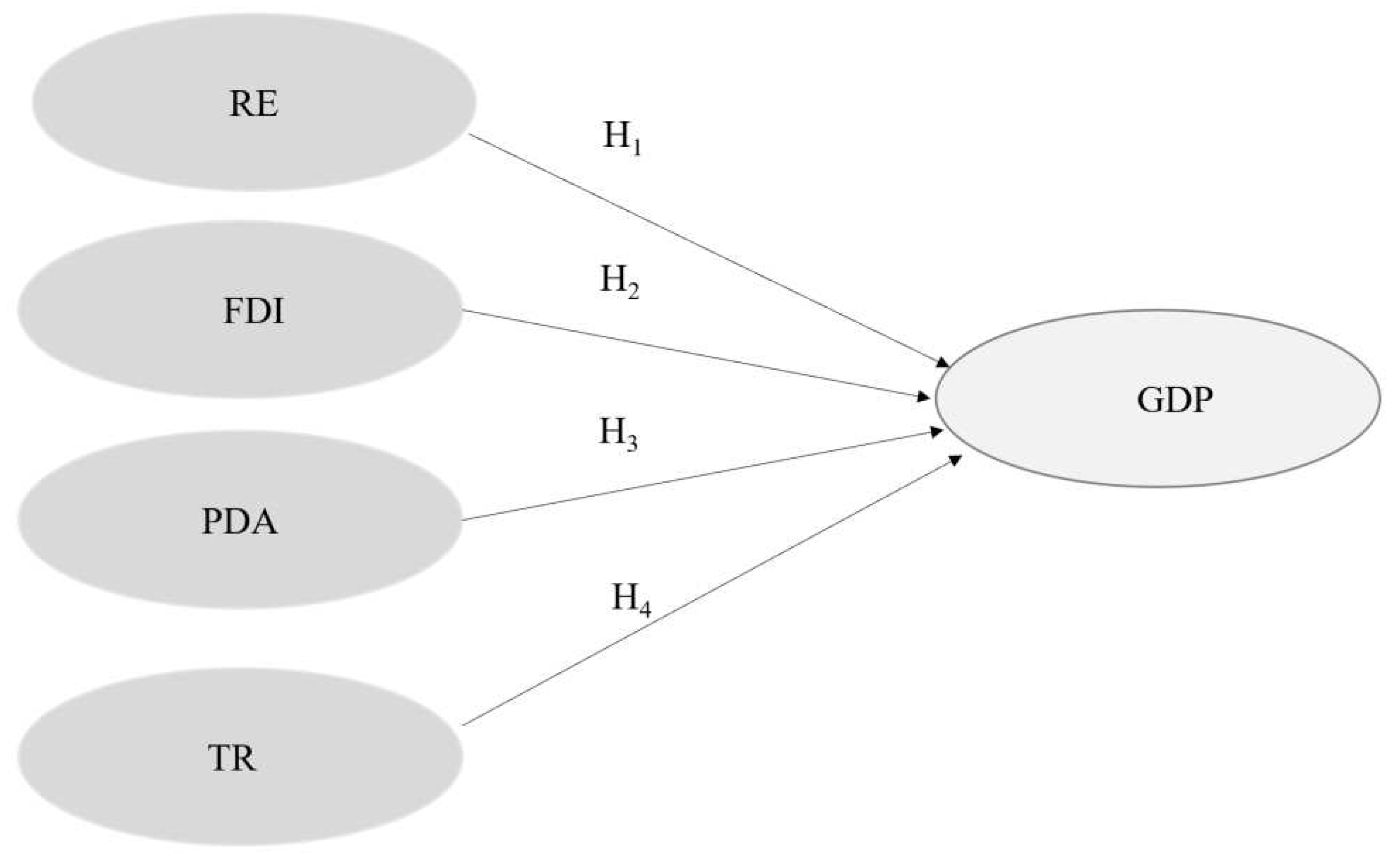

From the above discussion and theoretical we can present the following hypothesis:

H1: Remittances have the potential to contribute to GDP development.

H2: Foreign Direct Investment has the potential to contribute to GDP development.

H3: Public Development aid has the potential to contribute to GDP development.

H4: Tourism receipts have the potential to contribute to GDP development.

To contribute to the analyses of those hypothesis, models of linear regression were estimated, based on Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method, considering robust standard errors (none of the Gauss-Markov assumptions was violated), according to Wooldridge [55].

The dependent variable according to the hypothesis is GDP, and the explanatory ones are RE, FDI, PDA and TR according to Figure 4.

The estimated model is presented below.

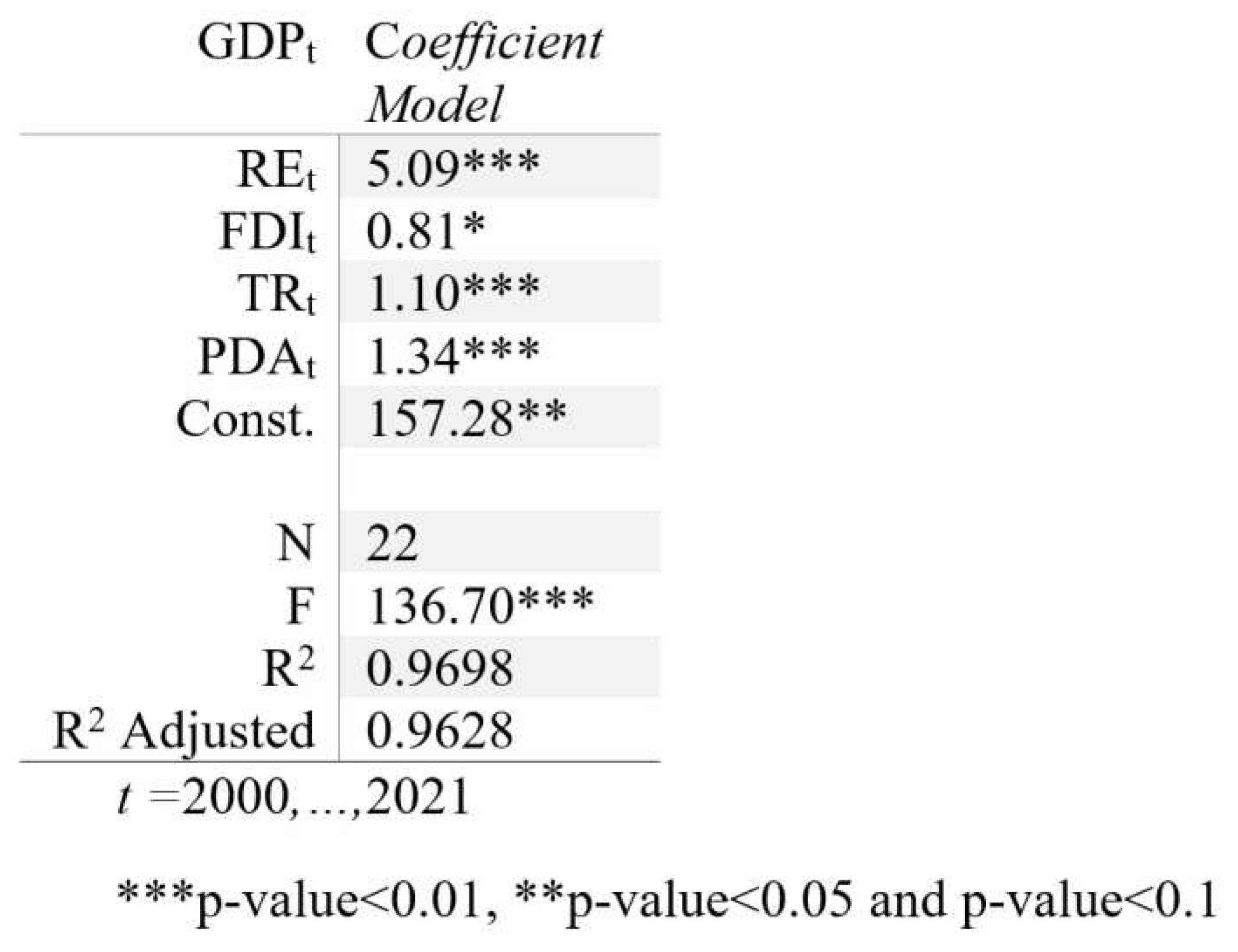

Figure 5.

Regression model estimated by Ordinary Least Square (OLS) with robust standard errors. Source: The authors.

Figure 5.

Regression model estimated by Ordinary Least Square (OLS) with robust standard errors. Source: The authors.

It can be observed that all the independent (explanatory) variables contributed positively to GDP and the coefficients associated to the independent variables are significant.

The four formulated hypothesis are validated, concluding that ceteris paribus, Remittances have the potential to contribute positively to GDP development, Foreign Direct Investment has the potential to contribute positively to GDP development, Public Development aid has the potential to contribute positively to GDP development and also

Tourism receipts have the potential to contribute positively to GDP development.

This opens new opportunities for government’s strategies in order to full maximize the various limited opportunities that several SIDS face on a daily basis.

Conclusion

Cape Verde as many other SIDS countries has suffered strongly during the pandemics. After some economic stagnation, in 2022, the country has witnessed a strong economic growth, due mainly due to the sectors of tourism, transport, and commerce. This surge in economic activity boosted the country's GDP and allowed to contribute to poverty reduction [49]. However, the country still faces several constraints as a result of its need for economic diversification and better resilience to external shocks, particularly climate related.

Regardless these aspects, there is no doubt that Cabo Verde has achieved impressive social and economic progress since its independence in 1975, despite its various geographical challenges and scarce resources.

The 2023 Economic Update is a comprehensive overview of Cabo Verde's economy in 2022. The report provides a clear understanding of the economic context and challenges faced by the country in the short term, facilitating the implementation of necessary reforms moving forward.

This paper has drawn upon Cape Verdean islander economic time series and has demonstrated that this SIDS, is a resilient country who has been using all the available opportunities. This paper contributes to the small body of literature on the island of Cape Verde and provides a snapshot, a case study over time. The 20 years of time series used in this paper demonstrates how islanders retain their commitments to their country.

Several small islands around the world have been noted for their resilience, flexibility, and chance-taking [3,10] as it happens in this economy.

Over time, national government has used multiple sources of incoming as a MIRAB model (migrations, remittances, aid and bureaucracy) but the main question is that this country may be on the edge of becoming a TOURAB economy due to the growing importance of tourism receipts and in some cases the loss of importance of other income sources.

So, we can stress the “dynamic flexibility,” p, 243 strategies that Cape Verde is adopting.

This paper made several contributions to the literature. It allowed to demonstrate that islandness is composed of shifts and rupture and the survival strategies, demonstrate their resilience since they have the capacity to adapt and change to the new international challenges.

Tourism on small remote islands has been adopted by many societies with good results in many economic development strategies.

The critical element of aid and bureaucracy is still an essential part of the economy in Cape Verde. Tourism has been reinforcing its importance. However, the tourism industry has been heavily supported by aid and bureaucracy and it doesn’t have yet the capacity to become a self-sustaining activity in the near future. The collected evidences of this research suggests that the TOURAB model may become the best model to describe the Cape Verdean economy transition.

While the MIRAB model may be considered an outdated model, the TOURAB model has not yet become the most reflective taxonomy for Cape Verde’s economic development. TOURAB still encompasses the aid and bureaucracy that are still very significative to Cape Verde.

The growing tourism industry is starting to provide a degree of economic diversification and if it keeps the same path as for now, tourism may become the most important economic activity. Thus, aid, bureaucracy and tourism in Cape Verde must be understood together, and to this end, the TOURAB model helps to reflect this changing.

Managerial impact

This research clearly shows the example a small island with several historical limitations that has impacted the economic growth. As seen over the text, politicians and managers must be aware of some challenges and vulnerabilities that have aroused over time because if they are well managed, they may become an opportunity to both diversify the economy and consequently contribute to reduce some of the unemployment rate, reduce poverty levels. If the Government is successful in this, then the country can provide better opportunities for investors and the creation of local companies along with international ones.

It is important to accept that tourism may be a push activity that must be wisely used in order to maximize its local impacts.

As stated before, the country still faces diverse challenges that need to be carefully addressed to ensure a sustainable and inclusive long-term economic growth. We can stress three priorities proposed by the World Bank (2023) (i) the importance of increasing firm-level productivity to generate more and better jobs; (ii) the need to reduce economic fragmentation by reduction transportation costs among islands; and (iii) the significance of building economic resilience to climate shocks.

If the country is successful, national authorities may gradually diversify its economy basis, improve firm-level productivity, prepare better for the impacts of climate shocks so that the country can foster a sustainable and inclusive growth, reduce poverty levels, and promote a shared prosperity for the country and its people. All these aspects play a significant role in any of these countries.

References

- Parker, C. ‘St Helena, an island between’: Multiple migrations, small island resilience, and survival. Island Studies Journal 2021, 16(1), 2021, 173-189. [CrossRef]

- Nurse, K. Dynamic trade policy for small island developing states: Lessons for the Pacific from the Caribbean. International Trade 2016 Working Paper, No. 2016/18.

- Baldacchino, G. Surfers of the ocean waves: Change management, intersectional migration and the economic development of small island states. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 2011 52(3), 236-246. [CrossRef]

- Bertram, G., & Watters, R. The MIRAB economy in South Pacific microstates. Pacific Viewpoint 1985 26, 497–519. [CrossRef]

- Guthunz, U. & von Krosigk, F. Tourism development in small Island states: From ‘MIRAB’ to ‘TOURAB’, in L. Briguglio, B. Archer, J. Jafari and G. Wall (eds.), Sustainable Tourism in Islands and Small States: Issues and Policies. Printer Press: New York, 1996.

- McElroy, J.L., & Morris, L. African Island development experiences: A cluster of models. Bank of Valletta Review 2002 26, 38–57.

- Connell, J. Niue: Embracing a culture of migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 2008 34(6), 1021–1040. [CrossRef]

- Nel, R. Applying development models to small island states: Is Niue a TOURAB country?. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 2020 61(3), 551-565. ISSN 1360-7456,. [CrossRef]

- McElroy, J.L., & Parry, C. The characteristics of small Island tourist economies. Tourism and Hospitality Research 2010, 10(4), 315–328.

- Baldacchino, G. Small Island States: vulnerable, resilient, doggedly perseverant or cleverly opportunistic? Etudes Caribeenes 2014 27-28. [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, G. The Routledge international handbook of island studies; Routledge: Abingdon, 2018.

- Kelman, Ila Islands of vulnerability and resilience: Manufactured stereotypes? Area. 52 2018 6–13. [CrossRef]

- Grydehøj, A. A future of island studies. Island Studies Journal 2017 12, 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. An island characteristic: Derivative vulnerabilities to indigenous and exogenous hazards. Shima 2009 3, 3–15.

- Silver, J. J., Gray, N. J., Campbell, L. M., Fairbanks, L. W., & Gruby, R. L. Blue economy and competing discourses in international oceans governance. The Journal of Environment & Development 2015 24, 135–160. [CrossRef]

- Bertram, G. Introduction: The MIRAB model in the twenty-first century, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 2006 47(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.E. Coefficient of Variation. In: Applied Multivariate Statistics in Geohydrology and Related Sciences; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1998. [CrossRef]

- King, R. Geography, islands and migration in an era of global mobility. Island Studies Journal 2009 4(1), 53-84. [CrossRef]

- Lam, K. (2020). Cape Verde: Society, Island identity and worldviews. Visual Ethnography 2020 9(1), 170-185.

- Scheyvens, R., & Biddulph, R. Inclusive Tourism Development. Tourism Geographies 2017 20, 589–609. [CrossRef]

- Su, M. M., Wall, G., & Wang, S. Yujiale fishing tourism and island development in Changshan Archipelago, Changdao, China. Island Studies Journal 2017 12, 127–142. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, K.D. Political economy and international labour migration: The case of Polynesians in New Zealand, New Zealand Geographer 1983 39(1), 29–42. [CrossRef]

- Opeskin, B., & MacDermott, T. Resources, population and migration in the Pacific: Connecting islands and rim. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 2009 50(3), 353–373. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Resilient transport in small island developing states: from a call for action to action; World Bank: USA, 2022.

- Monioudi, L., Asariotis, R., Becker, A., Bhat, C., Dowding-Gooden, D., Esteban, M., Feyen, L., Mentashi, L., Nikolau, A. & Nurse, L. Climate change impacts on critical international transportation assets of Caribbean Small Island Developing States (SIDS): the case of Jamaica and Saint Lucia. Regional Environmental Change 2018 18(8), 2211-2225. [CrossRef]

- Portner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Adams, H., Adler, C., Aldunce, P., Ali, E., Begum, R.A., Betts, R., Kerr, R.B., Biesbroek, R. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report 2022.

- Banerjee, O., Boyle, K., Rogers, C.T., Cumberbatch, J., Kanninen, B., Lemay, M., Schling, M. Estimating benefits of investing in resilience of coastal infrastructure in small island developing states: An application to Barbados. Marine Policy 2018 90, 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Meddeb, R. How innovation can shape a new type of development in small island developing states, Journal of International Affairs 2022 74(2), 97-108.

- Barclay, J., Wilkinson, E., White, C.S., Shelton, C., Forster, J., Few, R., Lorenzoni, I., Woolhouse, G., Jowitt, C., Stone, H. Historical trajectories of disaster risk in Dominica. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2019 10(2),149–165. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido-Lobaton, P. Aggregating governance indicators; World Bank: USA, 1999a.

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido-Lobaton, P. Governance matters; World Bank: USA, 1999b.

- Chauvet, L., & Collier, P. Development effectiveness in fragile states: Spill overs and turnarounds. Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics: Oxford University, 2004.

- Emara, N., & Chiu, I. The impact of governance on economic growth: The case of Middle Eastern and North African Countries. MPRA Paper 68603. 2015.

- Saha, S., Gounder, R., Campbell, N., & Su, J. J. Democracy and corruption: A complex relationship. Crime, Law, and Social Change 2014 61(3), 287–308. [CrossRef]

- Fosu, A. Political instability and economic growth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Development and Cultural Change 1992 40(4), 829–841. [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., & Perotti, R. The political economy of growth: A critical survey of the literature. The World Bank Economic Review 1994 8(3), 351–371. [CrossRef]

- Congdon Fors, H. Do island states have better institution? Journal of Comparative Economics 2014 42(1), 34–60. [CrossRef]

- Chand, R., Singh, R., Patel, A. & Jain, D. Export performance, governance, and economic growth: evidence from Fiji - a small and vulnerable economy. Cogent Economics & Finance 2020 8: 1802808. [CrossRef]

- Briguglio, L. Small Island developing states and their economic vulnerabilities, World Development 1995 23(9), 1615–1632. [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., & Wacziarg, R. Openness, country size and government. Journal of Public Economics 1998 9(3), 305–321. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, H., Kervenoael, D., Li, X., & Read, R. A comparison of the economic performance of different micro-states, and between micro-states and larger countries. World Development, 1998 26(4), 639–656. [CrossRef]

- Tisdell, C. A. The MIRAB Model of Small Island Economies in the Pacific and their Security Issues, Revised Version. Working Paper No. 58, 2014.

- Apostolopoulos, Y. & Gayle, D. Island tourism and sustainable development: Caribbean, Pacific, and Mediterranean experiences, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002.

- Watson, R. H. Tourism development in Niue and the impact of New Zealand’s aid. Unpublished Masters of Arts Thesis, Geography Department, University of Otago, 2019.

- McElroy, J.L., & Parry, C. The long-term propensity for political affiliation in Island microstates. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 2012 50(4), 403–421. [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, G. Managing the hinterland beyond: Two ideal-type strategies of economic development for small Island territories, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 2006 47(1), 45–46. [CrossRef]

- Keese, A. Managing the Prospect of Famine: Cape Verdean Officials, Subsistence Emergencies, and the Change of Elite Attitudes During Portugal’s Late Colonial Phase, 1939–1961. Itinerario 2012 36 (1), 49–70. [CrossRef]

- Santos, D. A Imagem do Cabo-verdianos nos Textos Portugueses 1784-1844; Livraria Pedro Cardoso: Cabo Verde, 2017.

- International Monetary Fund [IMF] IMF Staff Completes 2023 Article IV Consultation and Second Review under the Extended Credit Facility Arrangement with Cabo Verde; IMF: USA, 2003.

- Central Intelligence Agency. World Factbook. CIA: USA, 2023.

- Boza-Chirino, J., González-Hernández, M., De León-Ledesma, J. Aid management and public policies for development. A case study of Cape Verde. Iberoamerican Journal of Development Studies 2019 8(2), 6-27. [CrossRef]

- Park, R. An Analysis of Aid Information Management Systems (AIMS) in Developing Countries: Explaining the Last Two Decades. Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawái, 2017.

- Evolução das economias dos PALOPS e Timor-Leste.

- African Development Bank Group Cabo Verde Economic Outlook; ADBG: Africa, 2023.

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. Mason: Ohio, 2019.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the indicated indicators of Cape Verde, from 2000 to 2021. Source: The authors.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the indicated indicators of Cape Verde, from 2000 to 2021. Source: The authors.

Figure 4.

Hypothesis concerning the contribute to Cape Verde’s GDP. Source: The authors

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Cape Verde: Islands of Vulnerability or Resilience? A Transition from a MIRAB Model into a TOURAB One?

Eduardo Moraes Sarmento

et al.

,

2023

Climate Change Adaptation on Small Island States: An Assessment of Limits and Constraints

Walter Leal Filho

et al.

,

2021

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated