Submitted:

12 December 2023

Posted:

12 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Description of measles vaccination in the national immunization program

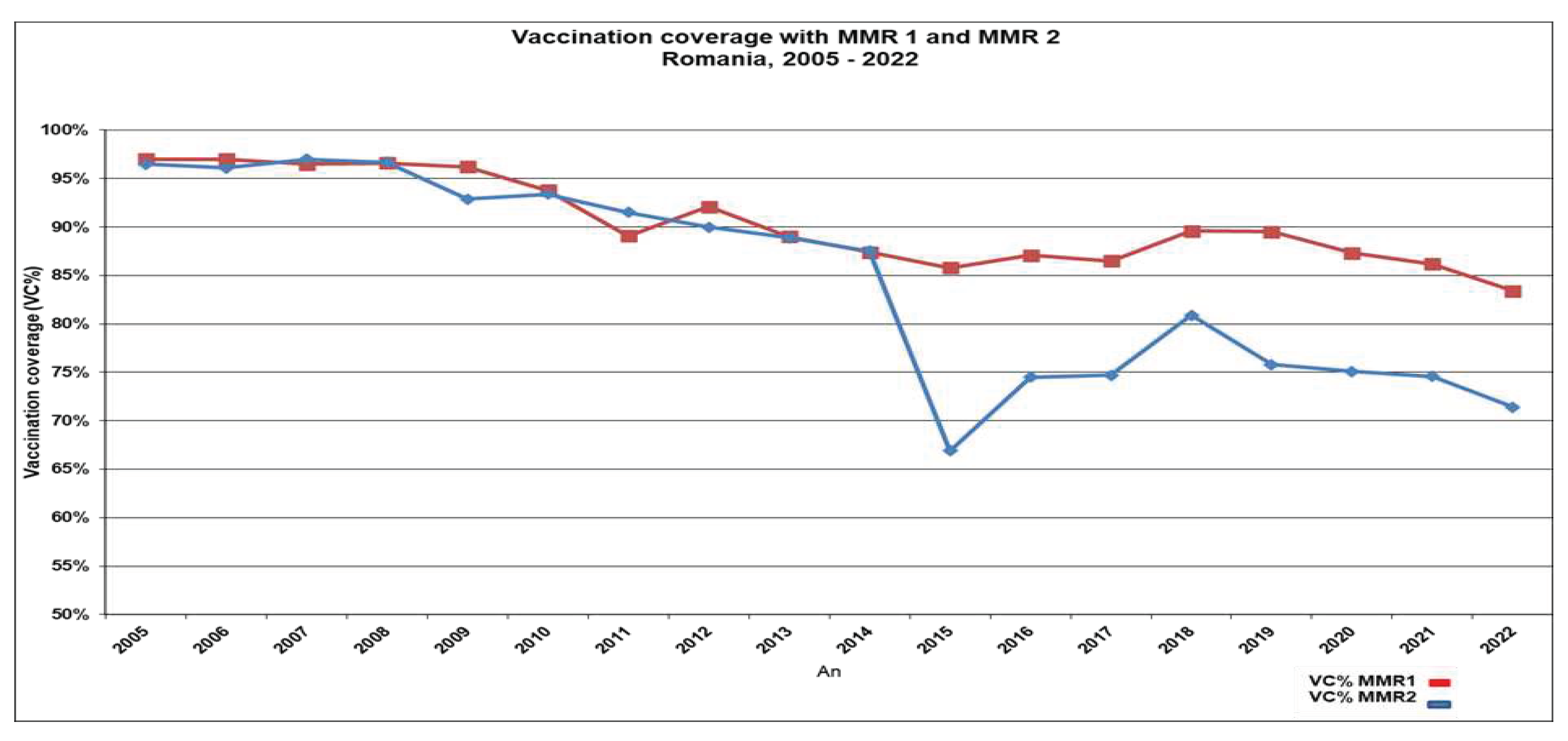

3.2. Evolution of vaccine coverage rates

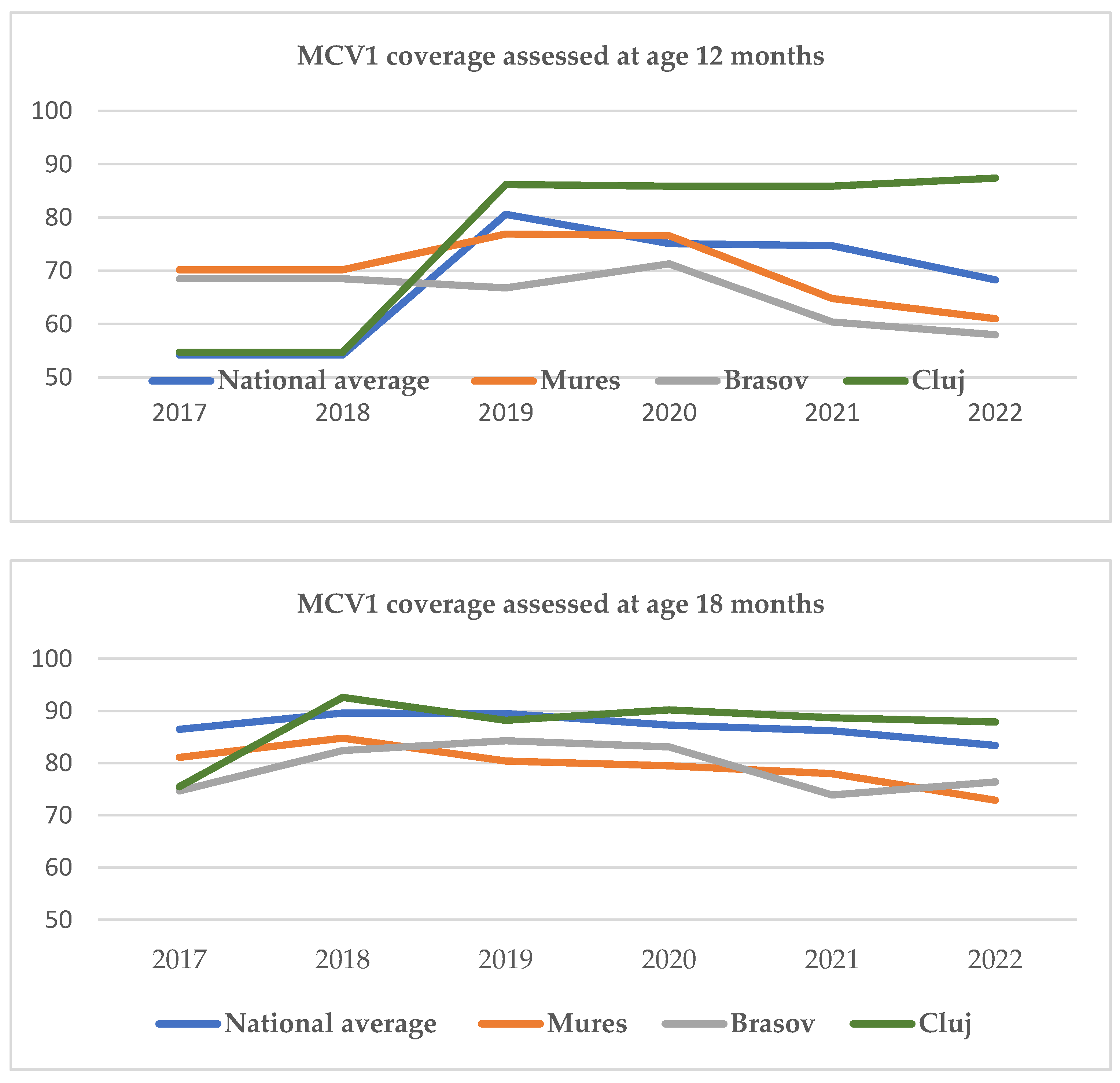

3.3. Sub-national vaccination coverage rates

3.4. Reasons for non-vaccination

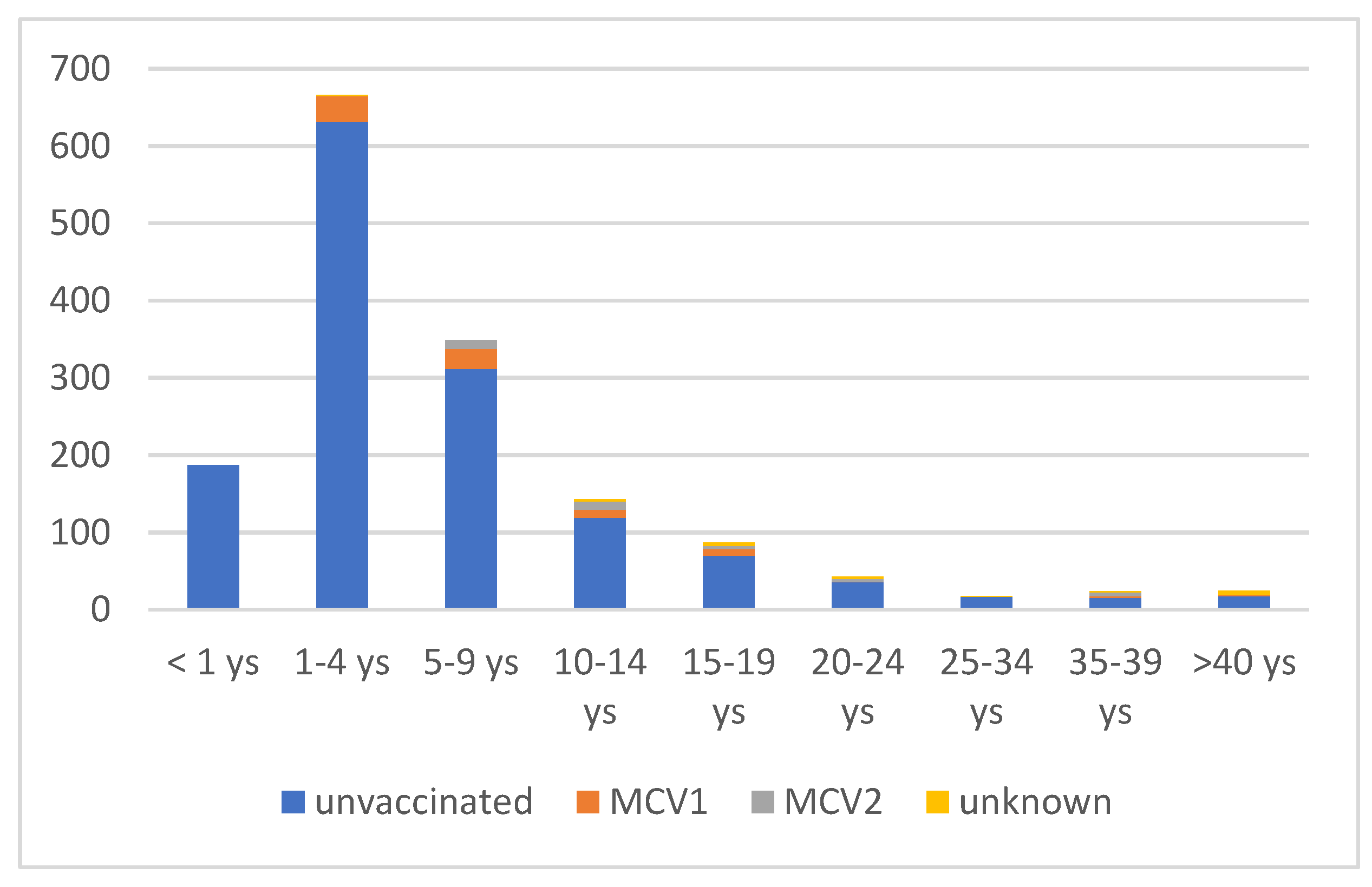

3.5. Measles incidence 2020-2023

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, Heffernan J, Deeks SL, Li Y, Crowcroft NS. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017, 17, e420–e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Measles and rubella strategic framework 2021–2030. Geneva:; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. ISBN 978-92-4-001562-3. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/339801/9789240015616-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- European Immunization Agenda 2030. Copenhagen:WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. ISBN: 978-92-890-5605-2.

- World Health Organization. WHO-UNICEF estimates of MCV1 coverage. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/timeseries/tswucoveragemcv1.html (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Sbarra AN, Mosser JF, Jit M, et al. Estimating national-level measles case-fatality ratios in low-income and middle-income countries: an updated systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2023, 11, e516–24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minta AA, Ferrari M, Antoni S, et al. Progress toward regional measles elimination—worldwide, 2000–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022, 71, 1489–95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minta AA, Ferrari M, Antoni S, et al. Progress Toward Measles Elimination — Worldwide, 2000–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:1262–1268. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Measles. In: ECDC. Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023.

- National Institute of Statistics. Statistical data (population by county). Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table.

- National Center for Disease Control. Evolution analysis of communicable diseases under surveillance, Annual reports. https://insp.gov.ro/centrul-national-de-supraveghere-si-control-al-bolilor-transmisibile-cnscbt/rapoarte-anuale/Romanian accessed January 2023.

- Ion-Nedelcu N, Craciun D, Pitigoi D, Popa M, Hennessey K, Roure C, Aston R, Zimmermann G, Pelly M, Gay N, Strebel P. Measles elimination: a mass immunization campaign in Romania. Am J Public Health 2001, 91, 1042-5. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Disease Control. Analysis of transmissible diseases evolution for 2010, available at https://www.cnscbt.ro/index.php/rapoarte-anuale/544-analiza-evolutiei-bolilor-transmisibile-aflate-in-supraveghere-raport-pentru-anul-2010. accessed June 2023.

- Stanescu A, Janta D, Lupulescu E, Necula G, Lazar M, Molnar G, Pistol A. Ongoing measles outbreak in Romania, 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011, 16, pii=19932.

- Lazar M, Abernathy E, Chen MH, Icenogle J, Janta D, Stanescu A, Pistol A, Santibanez S, Mankertz A, Hübschen JM, Mihaescu G, Necula G, Lupulescu E. Epidemiological and molecular investigation of a rubella outbreak, Romania, 2011 to 2012. Euro Surveill. 2016, 21, 30345. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health. National Centre for Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Control, Weekly reports. Romanian. Available from: https://insp.gov.ro/centrul-national-de-supraveghere-si-control-al-bolilor-transmisibile-cnscbt/informari-saptamanale/Accessed June 2023.

- Lazar M, Stănescu A, Penedos AR, Pistol A. Characterisation of measles after the introduction of the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 2004 with focus on the laboratory data, 2016 to 2019 outbreak. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24, 1900041. [CrossRef]

- Commission decision of 19 March 2002 laying down case definitions for reporting communicable diseases to the Community network under Decision No 2119/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (2002/253/EC), Official Journal of the European Communities 03.04.2002. Available online: http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2002:086:0044:0062:EN:PDF.

- Larson HJ, Gakidou E, Murray CJL. The Vaccine-Hesitant Moment. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jul 7;387(1):58-65. [CrossRef]

- Habersaat KB, Pistol A, Stanescu A, Hewitt C, Grbic M, Butu C, Jackson C. Measles outbreak in Romania: understanding factors related to suboptimal vaccination uptake. Eur J Public Health. 2020, 30, 986–992. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECDC. COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker, available at: https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#uptake-tab, accessed May 2023.

- Gastañaduy PA, Banerjee E, DeBolt C, Bravo-Alcántara P, Samad SA, Pastor D, Rota PA, Patel M, Crowcroft NS, Durrheim DN. Public health responses during measles outbreaks in elimination settings: Strategies and challenges. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018, 14, 2222–2238. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube E, Pistol A, Stanescu A, Butu C, Guirguis S, Motea O, Popescu AE, Voivozeanu A, Grbic M, Trottier MÈ, Brewer NT, Leask J, Gellin B, Habersaat KB. Vaccination barriers and drivers in Romania: a focused ethnographic study. Eur J Public Health. 2023, 33, 222–227. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics. The heath network activity in 2020, 2021, Romanian, available at https://insse.ro/cms/files/publicatii/publicatii%20statistice%20operative/activitatea_retelei_sanitare_in_anul_2020.pdf.

- Ministry of Health Romania. Annex to the Order of the Minister of Health nr. 2.931/2021 regarding the approval of the Manual of integrated community centers published in the Official Gazette of Romania No. 1240 bis, Romanian, available at https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/250002.

- Kriss JL, Stanescu A, Pistol A, Butu C, Goodson JL. The World Health Organization Measles Programmatic Risk Assessment Tool-Romania, 2015. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 1096–1107. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodyna R, Measles situation in Ukraine during the period 2017-2019. European Journal of Public Health 2019, 29 (Suppl 4), ckz186.496. [CrossRef]

- Lazar M, Pascu C, Roșca M, Stănescu A. Ongoing measles outbreaks in Romania, March 2023 to August 2023. Euro Surveill. 2023, 28, pii=2300423. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidance for host countries in the context of mass population movement from Ukraine WHO/EURO:2022-5135-44898-63834. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352373/WHO-EURO-2022-5135-44898-63834-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Ministry of Health. Romania Emergency ordinance No. 15/2022 on the provision of support and humanitarian assistance by the Romanian state to foreign citizens or stateless persons in special situations, coming from the area of the armed conflict in Ukraine.

- National Institute of Public Health. National Centre for Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Control, Weekly reports. Romanian. Vaccine coverage Romania, 2022. Available online: https://www.cnscbt.ro/index.php/analiza-date-supraveghere/evaluarea-acoperirii-vaccinale/3514-analiza-rezultatelor-estimarii-acoperirii-vaccinale-la-varsta-de-18-luni-februarie-2023/file (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s children. Regional Brief. European and Central Asia 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/reports/sowc2023-eca (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Communicable Disease Threats Report, week 5-11 November, 2023, available at file:///Users/simonaruta/Desktop/Aurora%20stanescu%20MMR/communicable-disease-threats-report-week-45-2023.pdf, accessed November 22, 2023.

- Ministry of Health, Romania. Order 3494/2023 for the approval of the Action Plan for the elimination of measles, rubella and prevention of congenital rubella infection/congenital rubella syndrome, Romanian, available at https://www.lege-online.ro/lr-PLAN-din%20-2022-(261696)-(9).html.

| Counties with VCR < 75% n, (%) |

Counties with VCR >90 % n, (%) |

Counties with VCR >95 % n, (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 12 mo | 18 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo |

| 2019 | 8 (19%) | 1 (2.3%) | 7 (16.6%) | 24 (57.1%) | 2 (52.3%) | 3(7.1%) |

| 2020 | 13 (30%) | 1 (2.3%) | 4 (9.5%) | 22 (52.3%) | 0 | 7(16.6%) |

| 2021 | 16 (38%) | 2 (4.6%) | 3 (7,1%) | 15 (35.7%) | 0 | 3 (7.1%) |

| 2022 | 31(73%) | 9 (21,4%) | 3 (7.1%) | 9 (21.4%) | 0 | 4 (9.5%) |

| County | MCV1 (%) 2022 | Number of eligible children aged 12 mo |

MCV2 (%) 2022 | Number of eligible children aged 5 ys |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National average | 83.4 | 71.4 | ||

| Mures | 72.9 | 4 665 | 68.7 | 6223 |

| Brasov | 76.4 | 5 175 | 59.4 | 6736 |

| Cluj | 87.9 | 6 399 | 73.4 | 7524 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).