Submitted:

11 December 2023

Posted:

12 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

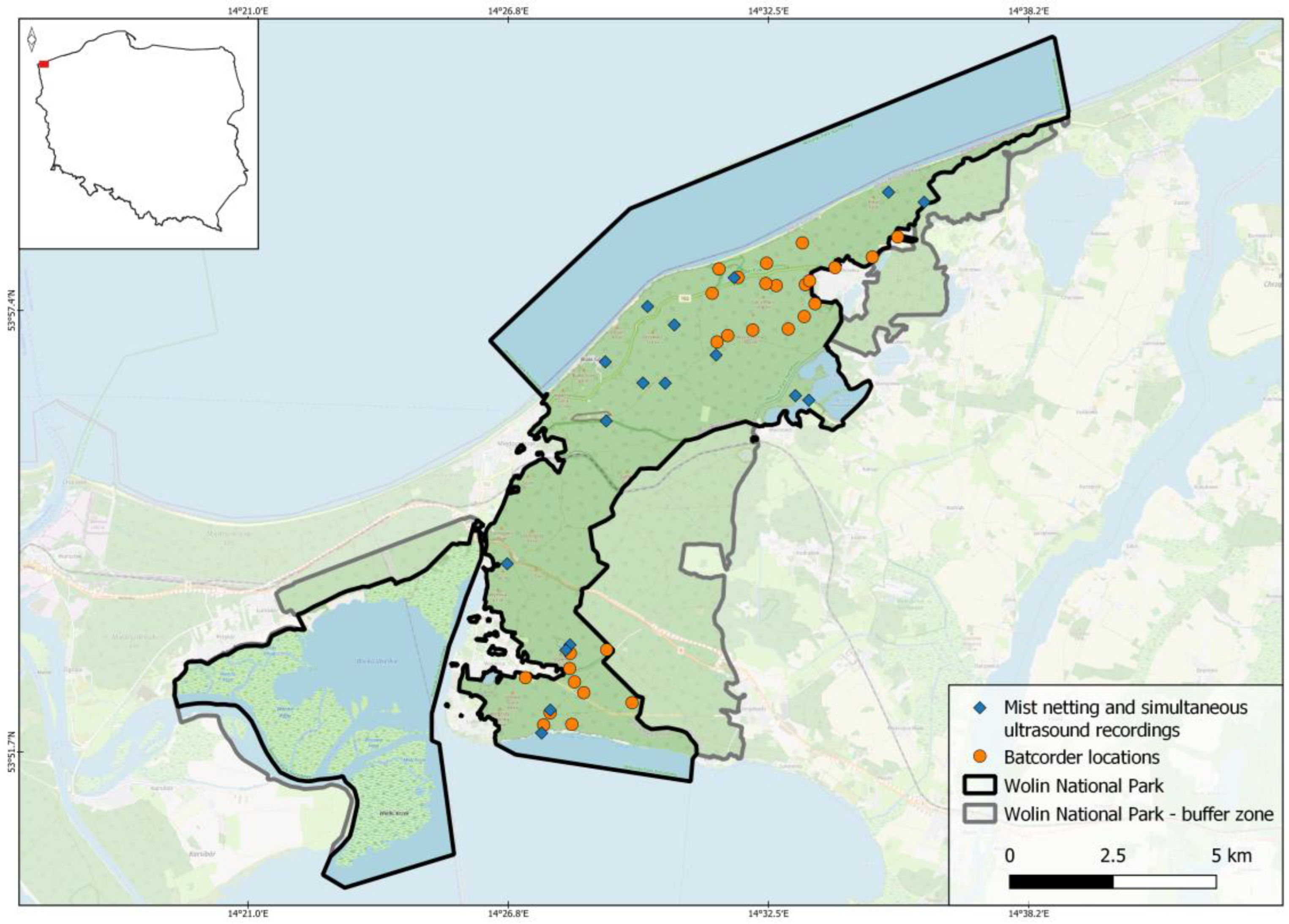

2.1. Study area

2.2. Data collection

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. General composition of bat fauna

3.2. Species composition revealed by different methods

| Species | mist-netting | D-1000X, MB and EMT detectors | Batcorder detectors | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw | adjusted | NL | raw | adjusted | NL | ||||||||

| n | % | NL | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| M. myotis | 1 | 0,2 | 1 | 4 | 0,06 | 5 | 0,09 | 3 | 1 | 0,01 | 1 | 0,01 | 1 |

| M. nattereri | 23 | 5,1 | 13 | 3 | 0,04 | 5 | 0,09 | 2 | 19 | 0,20 | 32 | 0,33 | 5 |

| M. daubentonii | 51 | 11,2 | 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Myotis sp. | - | - | - | 952 | 14,04 | 1590 | 27,46 | 9 | 762 | 8,04 | 1272 | 13,14 | 17 |

| E. serotinus | 5 | 1,1 | 4 | 156 | 2,30 | 98 | 1,70 | 10 | 76 | 0,80 | 48 | 0,49 | 12 |

| P. pipistrellus | 5 | 1,1 | 3 | 554 | 8,17 | 554 | 9,57 | 13 | 664 | 7,01 | 664 | 6,86 | 15 |

| P. pygmaeus | 273 | 60,0 | 14 | 2501 | 36,89 | 2501 | 43,19 | 16 | 5532 | 58,38 | 5532 | 56,99 | 20 |

| P. nathusii | 12 | 2,6 | 9 | 460 | 6,78 | 460 | 7,94 | 15 | 666 | 7,03 | 666 | 6,88 | 18 |

| Pipistrellus sp. | 2 | 0,4 | 1 | 38 | 0,56 | 38 | 0,66 | 6 | 1367 | 14,43 | 1367 | 14,11 | 20 |

| N. noctula | 59 | 13,0 | 5 | 1988 | 29,32 | 497 | 8,58 | 12 | 373 | 3,94 | 93 | 0,96 | 14 |

| N. leisleri | 6 | 1,3 | 1 | 120 | 1,77 | 37 | 0,64 | 8 | 10 | 0,11 | 3 | 0,03 | 4 |

| P. auritus | 18 | 4,0 | 4 | 4 | 0,06 | 5 | 0,09 | 3 | 6 | 0,06 | 7 | 0,08 | 5 |

| total | 455 | 100,0 | 17 | 6780 | 100,00 | 5790 | 100,00 | 16 | 9476 | 100,00 | 9706 | 100,00 | 20 |

| NEV | - | - | - | 18 | - | - | - | - | 325 | - | - | - | - |

| indet. | - | - | - | 30 | - | - | - | - | 1149 | - | - | - | - |

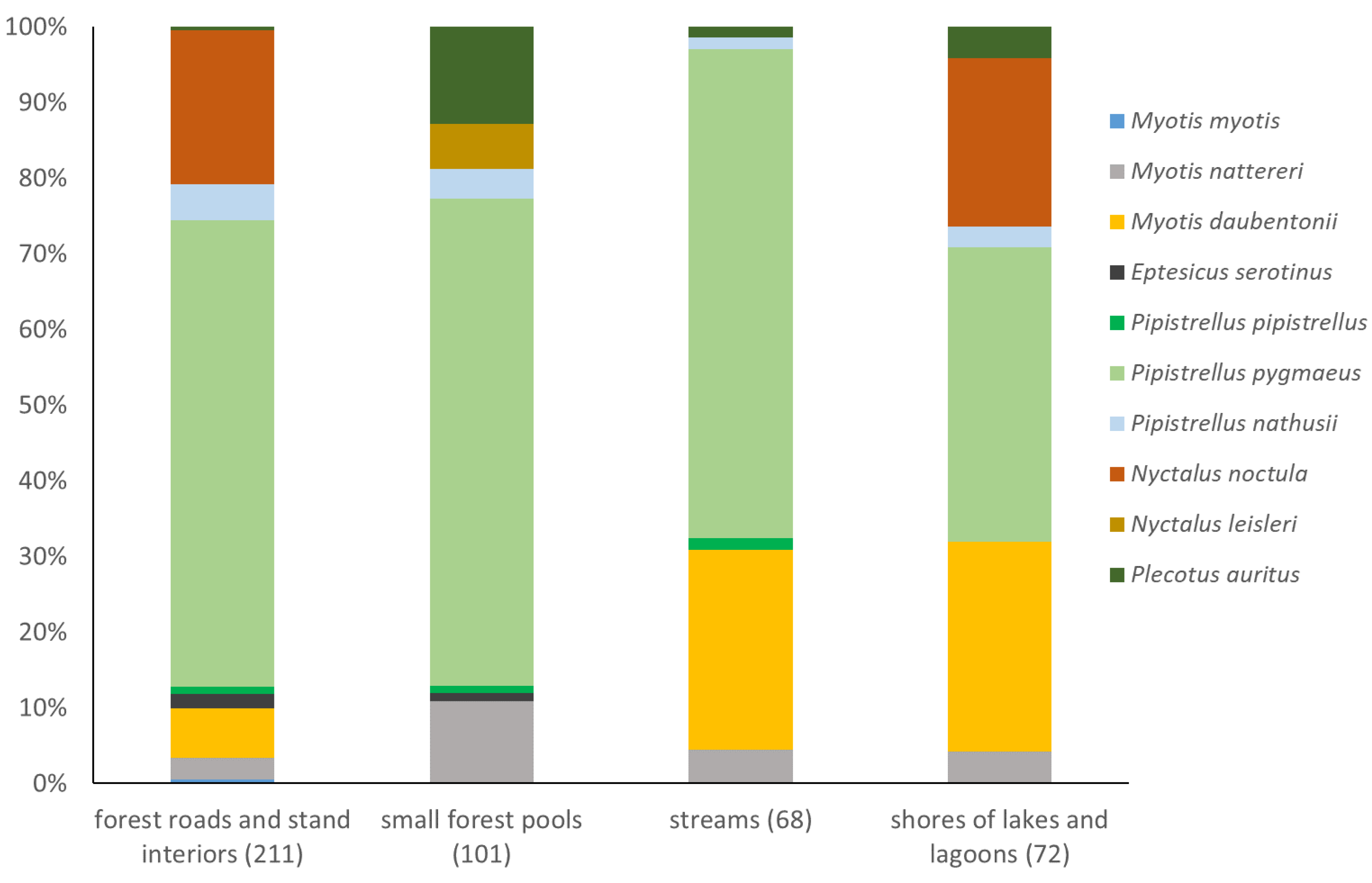

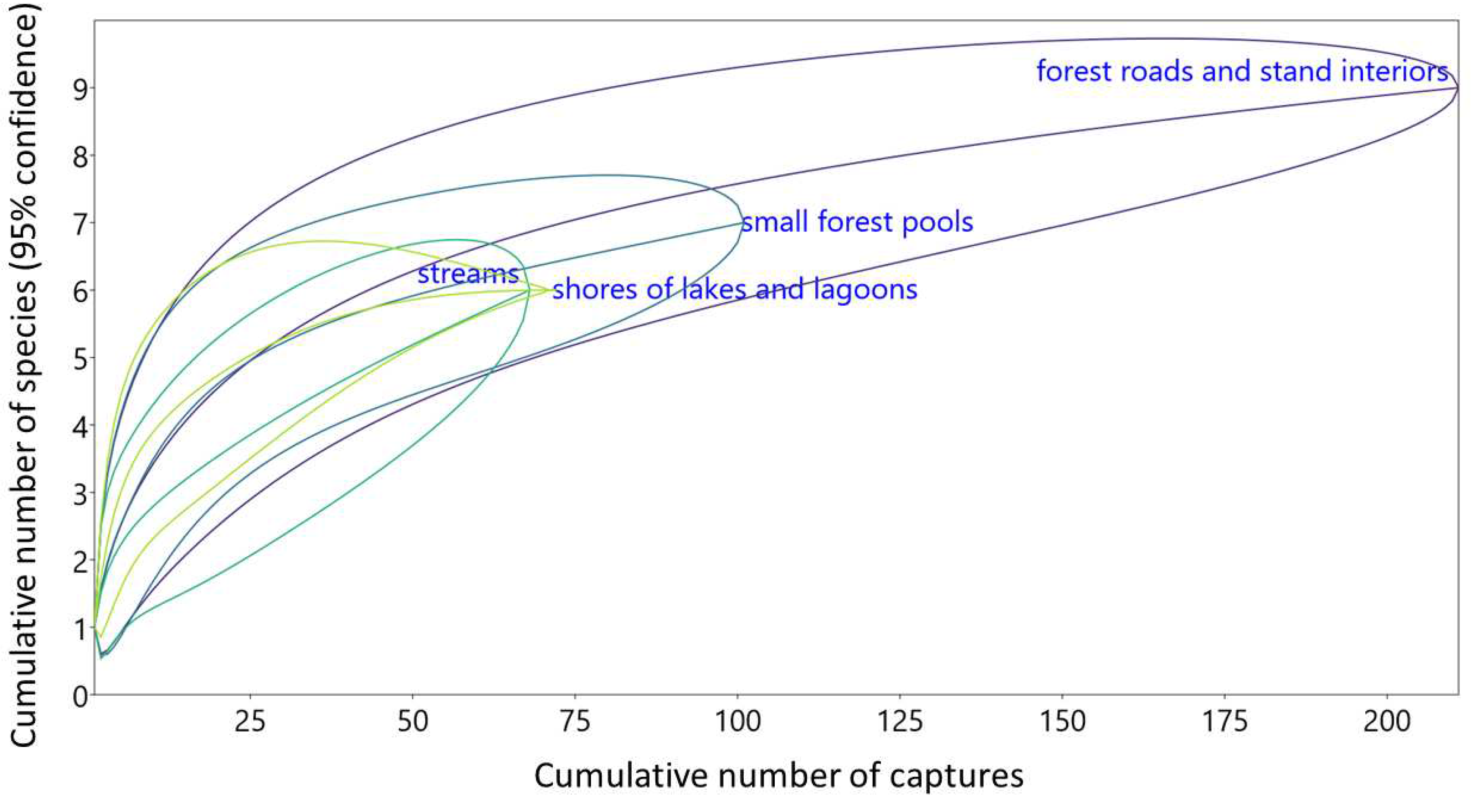

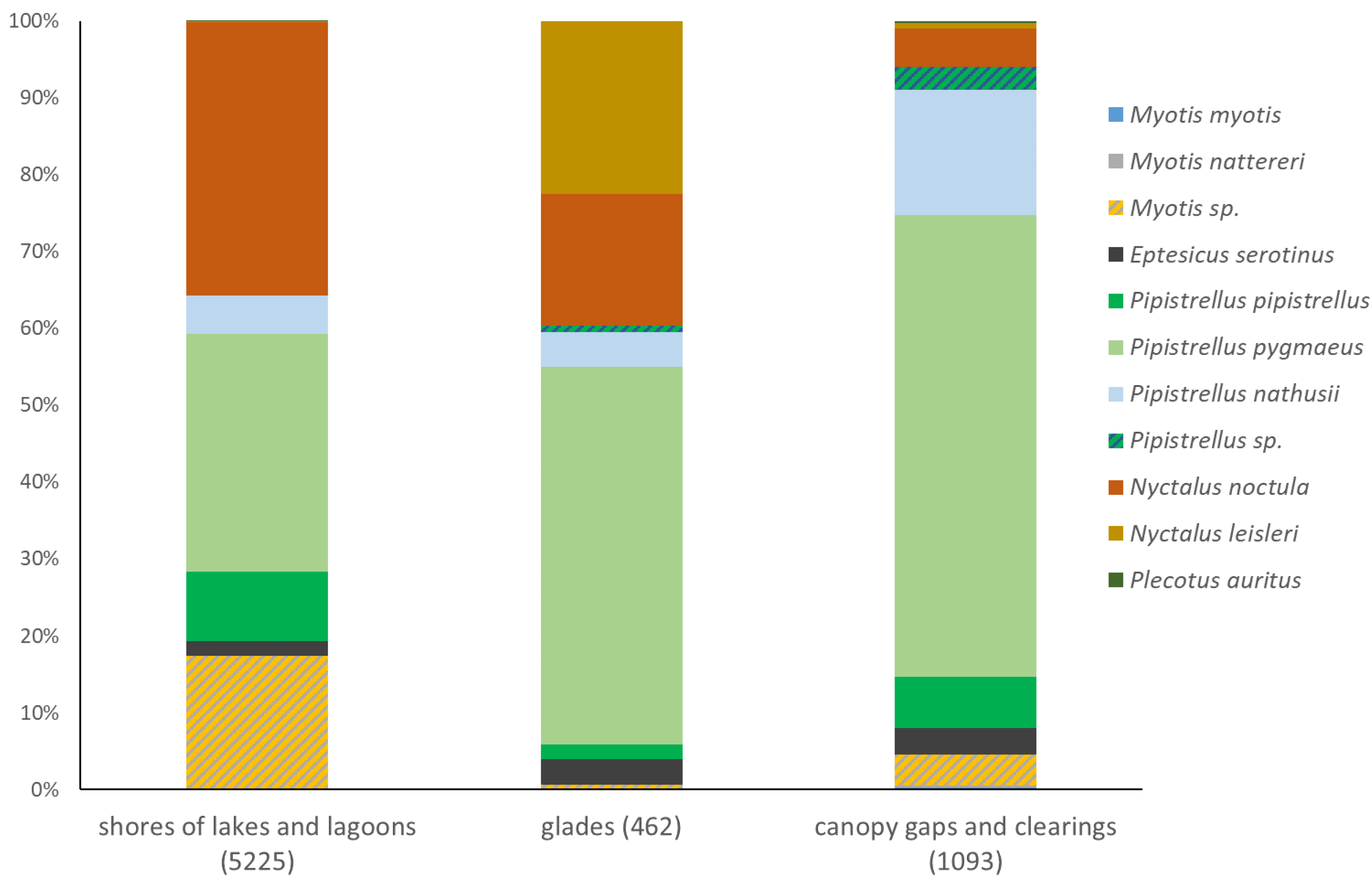

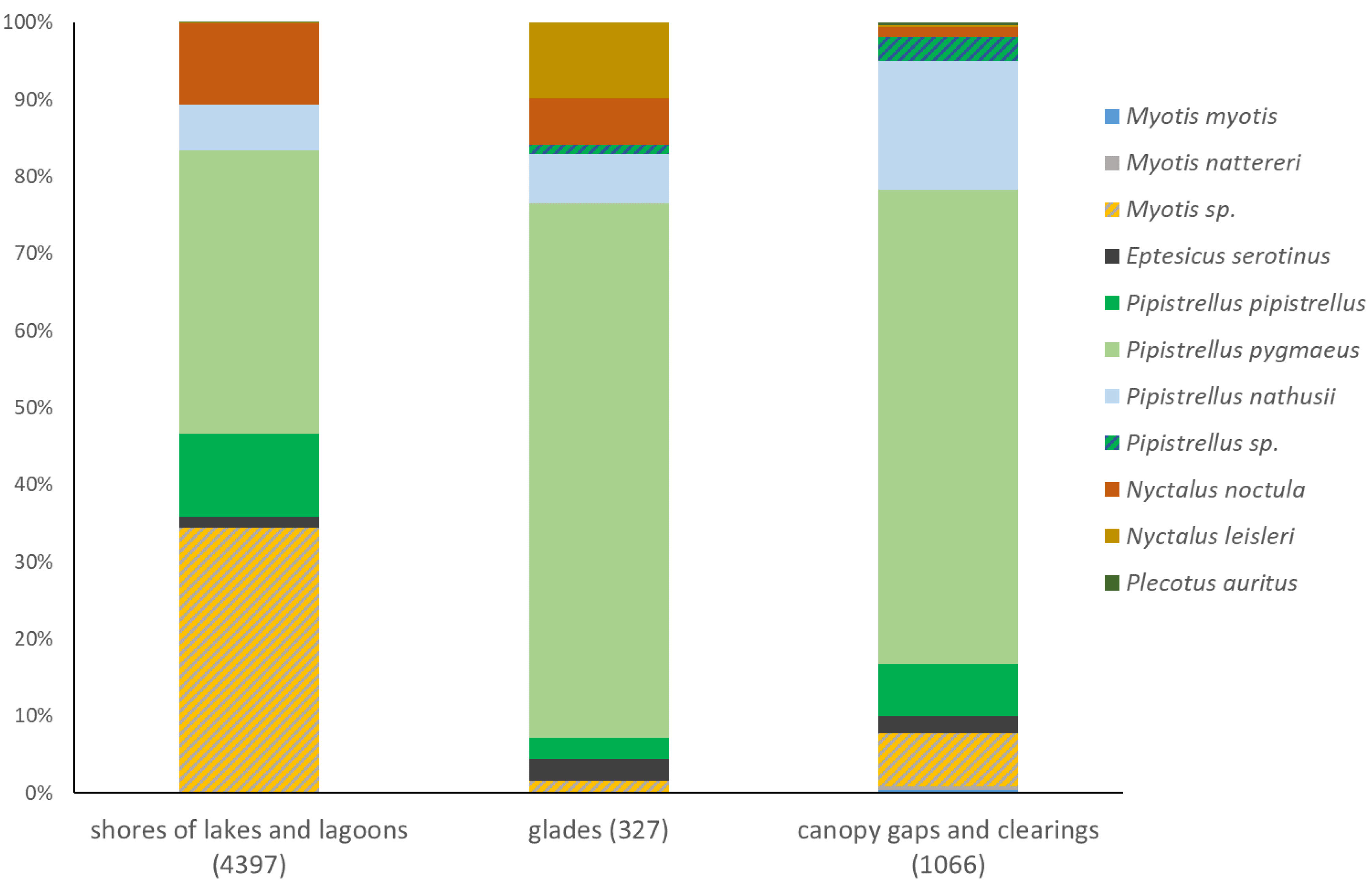

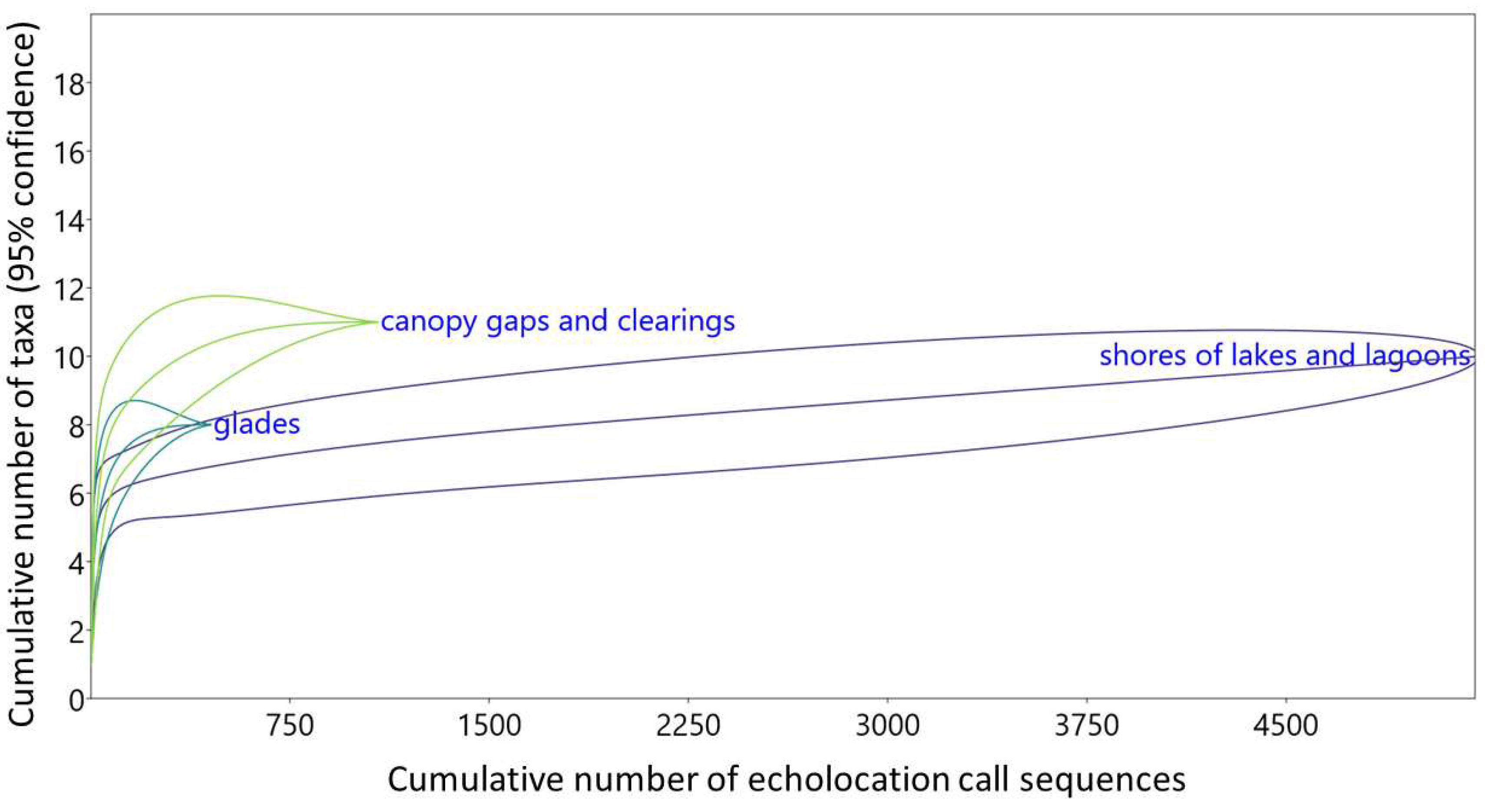

3.3. Structure of bat assemblages in different habitats

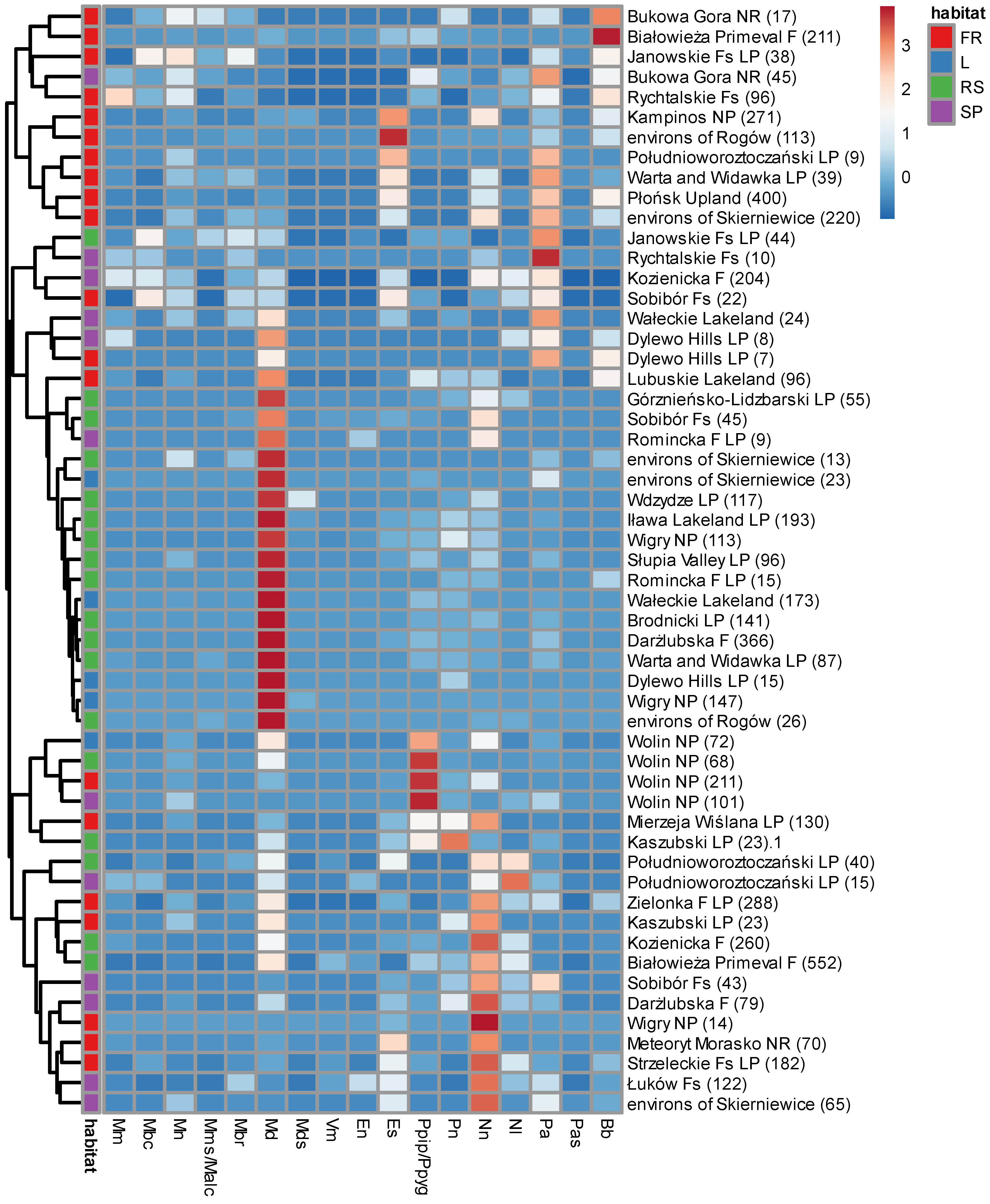

3.4. Comparison with the other Polish lowland forests

4. Discussion

4.1. General composition of bat fauna

4.2. Species composition revealed by different methods

4.2. Uniformization of bat assemblages accros habitats – unique feature of the Wolin National Park?

4.3. Factors behind hyperabundance of Pipistrellus pygmaeus and scarcity of forest specialists

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Law, B.; Park, K.J.; Lacki, M.J. Insectivorous Bats and Silviculture: Balancing Timber Production and Bat Conservation. In Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of Bats in a Changing World; Voigt, C., Kingston, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2016; pp. 105-150. [CrossRef]

- Böhm, S.M.; Wells, K.; Kalko E.K.V. Top-Down Control of Herbivory by Birds and Bats in the Canopy of Temperate Broad-Leaved Oaks (Quercus robur). PLoS ONE 2011, Volume 6(4): e17ila857. [CrossRef]

- Beilke, E.A.; O'Keefe, J.M. Bats Reduce Insect Density and Defoliation in Temperate Forests: An Exclusion Experiment. Ecology 2023, Volume 104(2): e3903. [CrossRef]

- Charbonnier, Y.; Barbaro, L.; Theillout, A.; Jactel, H. Numerical and Functional Responses of Forest Bats to a Major Insect Pest in Pine Plantations. PLoS ONE 2014, Volume 9(10): e109488. [CrossRef]

- Ancillotto, L.; Rummo, R.; Agostinetto, G.; Tommasi, N.; Garonna A.P.; Benedetta, F.; Bernardo, U.; Galimberti, A.; Russo, D. Bats as suppressors of agroforestry pests in beech forests. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, Volume 522, 120467. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, N. The diets of British bats (Chiroptera). Mammal Review 1997, Volume 27, pp. 77–94. [CrossRef]

- Vesterinen, E.; Puisto, A.; Blomberg, A.; Lilley, T. Table for five, please: Dietary partitioning in boreal bats. Ecology and Evolution 2018, Volume 8(3). [CrossRef]

- Findley, J. Bats. A community perspective. Cambridge Studies in Ecology; Cambridge University Press: New York, 1995; 167 pp.

- Jung, K.; Kaiser, S.; Böhm, S.; Nieschulze, J.; Kalko, E.K.V. Moving in three dimensions: effects of structural complexity on occurrence and activity of insectivorous bats in managed forest stands. Journal of Applied Ecology 2012, Volume 49, pp. 523–531. [CrossRef]

- Allegrini, C.; Korine, C.; Krasnov, B.R. Insectivorous Bats in Eastern Mediterranean Planted Pine Forests—Effects of Forest Structure on Foraging Activity, Diversity, and Implications for Management Practices. Forests 2022, Volume 13, no. 9: 1411. [CrossRef]

- Baagøe, H. J. The Scandinavian bat fauna: adaptive wing morphology, and free flight in the field. In Recent advances in the study of bats; Fenton M.B, Racey, P.A., Rayner J.M.V; Cambridge University Press: New York, 1987; pp. 57-74.

- Neuweiler, G. Foraging Ecology and Audition in Echolocating Bats. TREE 1989, Volume 6, pp. 160-166. [CrossRef]

- Węgiel, A.; Grzywiński, W.; Ciechanowski, M. The foraging activity of bats in managed pine forests of different ages. European Journal of Forest Research 2019, Volume 138, pp. 383–396. [CrossRef]

- Vlaschenko, A.; Kravchenko, K.; Yatsiuk, Y.; Hukov, V.; Kramer-Schadt, S.; Radchuk, V. Bat Assemblages Are Shaped by Land Cover Types and Forest Age: A Case Study from Eastern Ukraine. Forests 2022, Volume 13, no. 10: 1732. [CrossRef]

- Piksa, K.; Brzuskowski, T.; Zwijacz-Kozica, T. Distribution, Dominance Structure, Species Richness, and Diversity of Bats in Disturbed and Undisturbed Temperate Mountain Forests. Forests 2022, Volume 13, no. 1: 56. [CrossRef]

- Kaňuch, P.; Danko, Š.; Celuch, M.; Krištín, A.; Pjenčák, P.; Matis, Š.; Šmídt, J. Relating bat species presence to habitat features in natural forests of Slovakia (Central Europe), Mammalian Biology 2008, Volume 73, Issue 2, pp. 147-155. [CrossRef]

- Węgiel, A.; Grzywiński, W.; Jaros, R.; Łacka, A.; Węgiel, J. Comparison of the Foraging Activity of Bats in Coniferous, Mixed, and Deciduous Managed Forests. Forests 2023, Volume 14, no. 3: 481. [CrossRef]

- Tillon, L.; Bouget, C.; Paillet, Y.; Aulagnier, S. How does deadwood structure temperate forest bat assemblages? European Journal of Forest Research 2016, Volume 135, pp. 433–449. [CrossRef]

- Lesinski, G.; Kowalski, M.; Wojtowicz, B.; Gulatowska, J.; Lisowska, A. Bats on forest islands of different size in an agricultural landscape. Folia Zoologica 2007, Volume 56(2), pp. 153–161.

- Ceľuch, M.; Kropil, R. Bats in a Carpathian beech-oak forest (Central Europe): Habitat use, foraging assemblages and activity patterns. Folia Zoologica 2008, Volume 57(4), pp. 358–372.

- Humphrey, S.R. Nursery Roosts and Community Diversity of Nearctic Bats. Journal of Mammalogy 1975, Volume 56, Issue 2, pp. 321–346. [CrossRef]

- Ruczyński, I.; Bogdanowicz, W. Roost Cavity Selection by Nyctalus noctula and N. leisleri (Vespertilionidae, Chiroptera) in Białowieża Primeval Forest, Eastern Poland. Journal of Mammalogy 2005, Volume 86, Issue 5, pp. 921–930. [CrossRef]

- Lučan, R.K.; Andreas, M.; Benda, P.; Bartonička, T.; Březinová, T.; Hoffmannová, A.; Hulová, Š.; Hulva, P.; Neckářová, J.; Reiter, A.; Svačina, T.; Šálek, M.; Horáček, I. Alcathoe Bat (Myotis alcathoe) in the Czech Republic: Distributional Status, Roosting and Feeding Ecology. Acta Chiropterologica 2009, Volume 11(1), pp. 61-69. [CrossRef]

- Lesiński, G.; Olszewski, A.; Popczyk, B. Forest roads used by commuting and foraging bats in edge and interior zones. Polish Journal of Ecology 2011, Volume 59, pp. 611-616.

- Seibold, S.; Buchner, J.; Bässler, C.; Müller, J. Ponds in acidic mountains are more important for bats in providing drinking water than insect prey. Journal of Zoology 2013, Volume 290, pp. 302-308. [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.; Ancillotto, L.; Cistrone, L.; Libralato, N.; Domer, A.; Cohen, S.; Korine, C. (2019), Effects of artificial illumination on drinking bats: a field test in forest and desert habitats. Animal Conservation 2019, Volume 22, pp. 124-133. [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M.; Krasnodębski, I.; Sachanowicz, K.; Dróżdż, R.; Wojtowicz, B. Skład gatunkowy, wybiórczość kryjówek i miejsc żerowania nietoperzy w Puszczy Kozienickiej. Kulon 1996, Volume 1 (1-2), pp. 25-41.

- Ciechanowski M. Community structure and activity of bats (Chiroptera) over different water bodies. Mammalian Biology 2002, Volume 67, pp. 276-285. [CrossRef]

- Woliński Park Narodowy 2022. O parku. Ogólnie – położenie, powierzchnia, historia. Available online: https://wolinpn.pl/o-parku/ogolnie-polozenie-powierzchnia-historia/ (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Woliński Park Narodowy 2022. Ekosystemy leśne Wolińskiego Parku Narodowego. Statystyka. Available online: https://wolinpn.pl/przyroda-parku/statystyka/ (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Dietz, C.; Kiefer, A. Bats of Britain and Europe; Bloomsbury Natural History: London, 2016; 398 pp.

- Coleman, L.S.; Ford W.M.; Dobony, C.A.; Britzke, E.R. A comparison of passive and active acoustic sampling for a bat community impacted by white-nose syndrome. Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management 2014, Volume 5, pp. 217-226. [CrossRef]

- Barataud, M. Acoustic Ecology of European Bats. Species Identification, Study of Their Habitats and Foraging Behaviour; Biotope – Muséum national d’Historie naturelle: Paris, 2014; 352 pp.

- Brabant, R.; Laurent, Y.; Dolap, U.; Degraer, S.; Poerink, B.J. Comparing the results of four widely used automated bat identification software programs to identify nine bat species in coastal Western Europe. Belgian Journal of Zoology 2018, Volume 148(2), pp. 119–128. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.N.; Jones, G. Acoustic identification of twelve species of echolocating bat by discriminant function analysis and artificial neural networks. Journal of Experimental Biology 2000, Volume 203(Pt 17), pp. 2641-2656. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, R.; Harper, D.A.T.; RYAN P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 2001, Volume 4, pp. 1-9.

- Häussler, U.; Nagel, A.; Braun, M.; Arnold, A. External characters discriminating sibling species of European pipistrelles, Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Schreber, 1774) and P. pygmaeus (Leach, 1825). Myotis 1999, Volume 37, pp. 27-40.

- Helversen, O.V.; Holderied, M. 2003. Zur Unterscheidung von Zwergfledermaus (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) und Mückenfledermaus (Pipistrellus mediterraneus/pygmaeus) im Feld. Nyctalus (N.F.) 2003, Volume 8(5), pp. 420-426.

- Metsalu, T.; Vilo, J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, Volume 43(W1), pp. 566-570. [CrossRef]

- ClustVis. Available online: https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/ (accessed on 23.10.2023).

- Sachanowicz, K.; Ciechanowski, M.; Piksa, K. 2006. Distribution patterns, species richness and status of bats in Poland. Vespertilio 2006, Volume 9-10, pp. 151-173.

- Bidziński, K.; Ciechanowski, M.; Jankowska-Jarek, M.; Wikar, Z. (Department of Vertebrate Ecology and Zoology, University of Gdańsk, Poland). Unpublished data, 2023.

- Gaisler, J.; Hanák, V.; Hanzal, V.; Jarský, V. Results of bat banding in the Czech and Slovak Republics, 1948-2000. Vespertilio 2003, Volume 7, pp. 3-61.

- Hutterer, R.; Ivanova, T.; Meyer-Cords, C.H.; Rodrigues, L. Bat migration in Europe. A review of banding data and literature. Federal Agency for Nature Conservation in Germany 2005, Volume 28.

- Zyska, W.; Dylawerski, M.; Mackiewicz, R.; Skórkowski, R.; Szwarc, M.; Walczak, M.; Zyska, M.; Zyska, W. Występowanie nietoperzy w siedliskach leśnych Wolińskiego Parku Narodowego w latach 2018-2019 w tle wyników ocen prowadzonych w ostatnich 30 latach. Przegląd Przyrodniczy 2020, Volume 31, pp. 64-81.

- Ruprecht, A.L. Bats (Chiroptera). In: Atlas of Polish mammals; Pucek, Z., Raczyński, J.; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1983; pp. 62–82, maps 27–67.

- Schaub, A.; Schnitzler, H.U. Echolocation behavior of the bat Vespertilio murinus reveals the border between the habitat types “edge” and “open space”. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2007, Volume 61, pp. 513–523. [CrossRef]

- Zingg, P.E. (1990). Akustische Artidentifikation von Fledermäusen (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in der Schweiz. Revue Suisse de Zoologie 1990, Volume 97, pp. 263-294. [CrossRef]

- Baagøe, H. J. 2001. Danish bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera): Atlas and analysis of distribution, occurrence and abundance. Steenstrupia; Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001, 26, pp. 1–117.

- Ciechanowski, M.; Jakusz-Gostomska, A.; Żmihorski, M. Empty in summer, crowded during migration? Structure of assemblage, distribution pattern and habitat use by bats (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in a narrow, marine peninsula. Mammal Research 2016, Volume 61(1), pp. 45-55. [CrossRef]

- Keišs, O.; Spalis, D.; Pētersons, G. Funnel trap as a method for capture migrating bats in Pape, Latvia. Environmental and Experimental Biology 2021, Volume 19(1), 7–10. [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowski, M.; Szkudlarek, R. Pierwsze stwierdzenie mroczka pozłocistego Eptesicus nilssonii (Keyserling & Blasius, 1839) na Pomorzu. Nietoperze 2003, Volume 4, pp. 105–107.

- Ciechanowski, M.; Sachanowicz, K.; Kokurewicz, T. Rare or underestimated? – The distribution and abundance of the pond bat (Myotis dasycneme) in Poland. Lutra 2007, Volume 50, pp. 107-134.

- Ciechanowski, M. 2021. Myotis bechsteinii (Kuhl, 1817). Atlas ssaków Polski. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN, Kraków, Poland. Available online: https://www.iop.krakow.pl/Ssaki/gatunek/160 (accessed on 6th November 2023).

- Murray, K.; Britzke, E.; Hadley, B.; Robbins, L. Surveying bat communities: A comparison between mist nets and the Anabat II bat detector system. Acta Chiropterologica 1999, Volume 1, pp. 105-112.

- Flaquer, C.; Torre, I.; Arrizabalaga, A. Comparison of Sampling Methods for Inventory of Bat Communities, Journal of Mammalogy 2007, Volume 88, Issue 2, pp. 526–533. [CrossRef]

- MacSwiney G., M.C.; Clarke, F.M.; Racey, P.A. What you see is not what you get: the role of ultrasonic detectors in increasing inventory completeness in Neotropical bat assemblages. Journal of Applied Ecology 2008, Volume 45, pp. 1364-1371. [CrossRef]

- Rachwald, A.; Boratyński, P.; Nowakowski, W.K. 2001. Species composition and night-time activity of bats flying over rivers in Białowieża Primeval Forest (Eastern Poland). Acta Theriologica 2001, Volume 46(3), pp. 235-242. [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowski, M.; Zając, T.; Biłas, A.; Dunajski, R. Spatiotemporal variation in activity of bat species differing in hunting tactics: effects of weather, moonlight, food abundance, and structural clutter. Canadian Journal of Zoology 2007, Volume 85(12), pp. 1249-1263. [CrossRef]

- Chaves-Ramírez, S.; Castillo-Salazar, C.; Sánchez-Chavarría, M.; Solís-Hernández, H.; Chaverri, G. Comparing the efficiency of monofilament and regular nets for capturing bats. Royal Society Open Science 2021, Volume 8:211404. [CrossRef]

- Siemers, B.; Schnitzler, HU. Echolocation signals reflect niche differentiation in five sympatric congeneric bat species. Nature 2004, Volume 429, pp. 657–661. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, N.; Jones, G.; Harris, S. Identification of British bat species by multivariate analysis of echolocation call parameters. Bioacoustics 1997a, Volume 7(3), pp. 189 - 207. [CrossRef]

- Walters, C.L.; Freeman, R.; Collen, A.; Dietz, C.; Brock Fenton, M.; Jones, G.; Obrist, M.K.; Puechmaille, S.J.; Sattler T.; Siemers, B.M.; Parsons, S.; Jones, K.E. A continental-scale tool for acoustic identification of European bats. Journal of Applied Ecology 2012, Volume 49, Issue 5, pp. 1064-1074. [CrossRef]

- Fenton, M.B. Choosing the 'correct' bat detector. Acta Chiropterologica 2000, Volume 2, pp. 215-224.

- Adams, A.M.; Jantzen, M.K.; Hamilton, R.M; Fenton, M.B. Do you hear what I hear? Implications of detector selection for acoustic monitoring of bats. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2012, Volume 3, pp. 992-998. [CrossRef]

- Rachwald, A.; Wodecka, K.; Malzahn, E; Kluziński, L. Bat activity in coniferous forest areas and the impact of air pollution. Mammalia 2004, Volume 68, no. 4, pp. 445-453. [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowski, M. Habitat preferences of bats in anthropogenically altered, mosaic landscapes of northern Poland. European Journal of Wildlife Research 2015, 61, pp. 415–428. [CrossRef]

- Rachwald, A.; Boratyński, J.S.; Krawczyk, J.; Szurlej, M.; Nowakowski, W.K. Natural and anthropogenic factors influencing the bat community in commercial tree stands in a temperate lowland forest of natural origin (Białowieża Forest). Forest Ecology and Management 2021, Volume 479, 118544. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, M.; Encarnação, J.A.; Kalko, E.K.V. Small scale distribution patterns of female and male Daubenton's bats (Myotis daubentonii), Acta Chiropterologica 2006, Volume 8(2), pp. 403-415. [CrossRef]

- Kurek, K.; Tołkacz, K.; Mysłajek, R. Low abundance of the whiskered bat Myotis mystacinus (Kuhl, 1817) in Poland — consequence of competition with pipistrelle bats? Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 2017, Volume 15, pp. 241–248. [CrossRef]

- Rachwald, A.; Bradford, T.; Borowski, Z.; Racey, PA. Habitat Preferences of Soprano Pipistrelle Pipistrellus pygmaeus (Leach, 1825) and Common Pipistrelle Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Schreber, 1774) in Two Different Woodlands in North East Scotland. Zoological Studies 2016, Volume 55:e22. [CrossRef]

- Rachwald, A. Występowanie mopka zachodniego Barbastella barbastellus (Schreber, 1744) w Puszczy Białowieskiej na tle innych gatunków nietoperz. In Inwentaryzacja wybranych elementów przyrodniczych i kulturowych Puszczy Białowieskiej; Matuszkiewicz, J.M, Tabor, J., Eds.; Instytut Badawczy Leśnictwa, Sękocin Stary, Poland, 2022; pp. 713–737. [CrossRef]

- Gaisler J. 1989. The r-K selection model and life history strategies in bats. In European bat research; Hanak V. Horácek I. Gaisler J., Eds.; Charles University Press, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1989; pp. 117–124.

- Arlettaz, R.; Godat, S.; Meyer, H. Competition for food by expanding pipistrelle bat populations (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) might contribute to the decline of lesser horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposideros). Biological Conservation 2000, Volume 93, Issue 1, pp. 55-60. [CrossRef]

- Mickleburgh, S. Distribution and status of bats in the London area. In European bat research; Hanak, V., Horácek, I., Gaisler, J., Eds.; Charles University Press, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 2989, pp. 327–329.

- Glendell, M.; Vaughan, N. Foraging activity of bats in historic landscape parks in relation to habitat composition and park management. Animal Conservation 2002, Volume 5, pp. 309-316. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, N.; Jones, G.; Harris, S. Habitat Use by Bats (Chiroptera) Assessed by Means of a Broad-Band Acoustic Method. Journal of Applied Ecology 1997b, Volume 34(3), pp. 716–730. [CrossRef]

- Russ, J.M.; Montgomery, W.I. Habitat associations of bats in Northern Ireland: implications for conservation. Biological Conservation 2002, Volume 108, Issue 1, pp. 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Sattler, T.; Bontadina, F.; Hirzel, A.H.; Arlettaz, R. Ecological niche modelling of two cryptic bat species calls for a reassessment of their conservation status. Journal of Applied Ecology 2007, Volume 44, pp. 1188-1199. [CrossRef]

- Stone, E.L.; Zeale, M.R.K.; Newson, S.E.; Browne, W.J.; Harris, S.; Jones, G. (2015). Managing conflict between bats and humans: The response of soprano pipistrelles (Pipistrellus pygmaeus) to exclusion from roosts in houses. PLoS ONE 2015, Volume 10(8), [e0131825]. [CrossRef]

- Michaelsen, T.C.; Jensen, K.H.; Högstedt, G. Roost Site Selection in Pregnant and Lactating Soprano Pipistrelles (Pipistrellus pygmaeus Leach, 1825) at the Species Northern Extreme: The Importance of Warm and Safe Roosts. Acta Chiropterologica 2014, Volume 16(2), pp. 349-357. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, M.; Brombacher, M.; Erasmy, M.; Fenchuk, V.; Simon, O. Bat Community and Roost Site Selection of Tree-Dwelling Bats in a Well-Preserved European Lowland Forest. Acta Chiropterologica 2018, Volume 20(1), pp. 117-127. [CrossRef]

- Bashta, A.-T. Bridge structures and habitats of bats (Chiroptera): species and spatial diversity. Theriologia Ukrainica 2022, Volume 24, pp. 86-103.

- Jenkins, E.V.; Laine, T.; Morgan, S.E.; Cole, K.R.; Speakman, J.R. Roost selection in the pipistrelle bat, Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae), in northeast Scotland. Animal Behaviour 1998, Volume 56(4), pp. 909-917. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, K.E.; Jones, G. Roosts, echolocation calls and wing morphology of two phonic types of Pipistrellus pipistrellus. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 1999, Volume 64, pp. 257–268.

- Kirkpatrick, L.; Graham, J.; McGregor, S.; Munro, L.; Scoarize, M. Flexible foraging strategies in Pipistrellus pygmaeus in response to abundant but ephemeral prey. PLOS ONE 2018, Volume 13(10): e0204511. [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.F.; Hiltunen, J.K. CHANGES IN THE BOTTOM FAUNA OF WESTERN LAKE ERIE FROM 1930 TO 1961. Limnology and Oceanography 2003, Volume 10, pp. 551-569. [CrossRef]

- Rachwald, A.; Ciesielski, M.; Szurlej, M.; Żmihorski, M. Following the damage: Increasing western barbastelle bat activity in bark beetle infested stands in Białowieża Primeval forest. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, Volume 503, 119803. [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.; Cistrone, L.; Jones, G.; Mazzoleni, S. Roost selection by barbastelle bats (Barbastella barbastellus, Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in beech woodlands of central Italy: consequences for conservation. Biological Conservation 2004, Volume 117, Issue 1, pp. 73-81. [CrossRef]

- Cel’uch, M.; Danko. S.; Kaňuch P. On urbanisation of Nyctalus noctula and Pipistrellus pygmaeus in Slovakia. Vespertilio 2006, 9-10, pp. 219-221.

- Friedland, R.; Schernewski, G.; Gräwe ,U.; Greipsland, I.; Palazzo, D.; Pastuszak, M. Managing Eutrophication in the Szczecin (Oder) Lagoon-Development, Present State and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in Marine Science 2019, Volume 5. [CrossRef]

- Andreas, M.; Reiter, A.; Benda, P. Prey Selection and Seasonal Diet Changes in the Western Barbastelle Bat (Barbastella barbastellus). Acta Chiropterologica 2012, Volume 14(1), pp. 81-92. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.H.; Gibson, L.; Amir, Z.; Chanthorn, W.; Ahmad, A.H.; Jansen, P.A.; Mendes, C.P.; Onuma, M.; Peres, C.A.; Luskin, M.S. The rise of hyperabundant native generalists threatens both humans and nature. Biological Reviews 2023, Volume 98, Issue 5, pp. 1829-1844. [CrossRef]

- Szyp, E. Nietoperze Brodnickiego Parku Krajobrazowego. MSc Thesis.. Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Institute of Biology, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń, Poland, 1996.

- Ciechanowski, M.; Koziróg, L.; Dariusz, J.; Przesmycka, A.; Świątkowska, A.; Kisicka, I.; Kasprzyk, K. Bat fauna of the Iława Lakeland Landscape Park (northern Poland. Myotis 2002, Volume 40, pp. 33-45.

- Bugajna B. Wstępne badania nad nietoperzami (Chiroptera) rezerwatu „Meteoryt Morasko”. Rocznik Naukowy Polskiego Towarzystwa Ochrony Przyrody Salamandra 1996, Volume 1, pp. 217-218.

- Ciechanowski, M.; Czablewska, A.; Mączyńska, M.; Narczyński, T.; Przesmycka, A.; Zapart, A.; Jarzembowski, T.; Rachwald, A. Nietoperze (Chiroptera) Parku Krajobrazowego „Mierzeja Wiślana”. Nietoperze 2008, Volume 9(2), pp. 203-224.

- Piskorski, M.; Urban, P. Nietoperze Południoworoztoczańskiego Parku Krajobrazowego. Nietoperze 2003, Volume 4(1), pp. 21-25.

- Sachanowicz, K.; Krasnodębski, I. Skład gatunkowy i antropogeniczne kryjówki nietoperzy w Lasach Łukowskich. Nietoperze 2003, Volume 4(1), pp. 27-38.

- Ciechanowski, M. Chiropterofauna Puszczy Darżlubskiej. Nietoperze 2003, Volume 4(1), pp. 45 – 59.

- Ciechanowski, M. Struktura przestrzenna zespołu i dynamika aktywności nietoperzy (Chiroptera) w krajobrazie leśno-rolniczym północnej Polski. PhD Thesis, Department of Vertebrate Ecology and Zoology, University of Gdańsk, Poland, 2005.

- Ignaczak M. Nietoperze rezerwatu „Bukowa Góra”. Nietoperze 2003, Volume 4(1), pp. 101 – 102.

- Ciechanowski, M.; Duriasz, J. Nietoperze (Chiroptera) Parku Krajobrazowego Wzgórz Dylewskich Nietoperze 2005, Volume 6(1-2), pp. 25-36.

- Ciechanowski, M.; Anikowska, U.; Nalewaja, A.; Przesmycka, A.; Biała, A. Nietoperze (Chiroptera) Parku Krajobrazowego „Dolina Słupi”. Nietoperze 2006, Volume 7(1 – 2), pp. 19 – 37.

- Lesiński, G.; Gulatowska, J.; Kowalski, M.; Fuszara, E.; Fuszara, M.; Wojtowicz, B. Nietoperze Wysoczyzny Płońskiej. Nietoperze 2006, Volume 7(1 – 2), pp. 39 – 55.

- Piskorski, M. Fauna nietoperzy Parku Krajobrazowego Lasy Janowskie. Nietoperze 2007, Volume 8(1 – 2), pp. 3 – 11.

- Piskorski, M.; Gwardjan, M.; Kowalski, M.; Wojtowicz, B.; Urban, M.; Bochen, R. Fauna nietoperzy Parku Krajobrazowego Lasy Strzeleckie. Nietoperze 2009, Volume 10(1 – 2), pp. 15 – 22.

- Łochyński, M.; Grzywiński, W. Nietoperze Parku Krajobrazowego Puszcza Zielonka. Nietoperze 2009, Volume 10(1 – 2), pp. 23 – 35.

- Piskorski M. Fauna nietoperzy Lasów Sobiborskich. Nietoperze 2008, Volume 9(1), pp. 3 – 17.

- Kmiecik, A.; Kmiecik, P.; Grzywiński, W. 2010. Chiropterofauna Wigierskiego Parku Narodowego. Nietoperze 2010, Volume 11(1 – 2), pp. 11 – 29.

- Postawa, T.; Gas, A. Fauna nietoperzy Wigierskiego Parku Narodowego (północno-wschodnia Polska). Studia Chiropterologica 2003, Volume 3–4, pp. 31–42.

- Sachanowicz, K.; Marzec, M.; Ciechanowski, M.; Rachwald, A.; Nietoperze Puszczy Rominckiej. Nietoperze 2001, Volume 2(1), pp. 109-115.

- Kowalski, M.; Ostrach-Kowalska, A.; Krasnodębski, I.; Sachanowicz, K.; Ignaczak, M.; Rusin, A. Nietoperze Parków Krajobrazowych: Górznieńsko-Lidzbarskiego i Welskiego. Nietoperze 2001, Volume 2, pp. 117-124.

- Ignaczak, M.; Radzicki, G.; Domański, J. Nietoperze Parku Krajobrazowego Międzyrzecza Warty i Widawki. Nietoperze 2001, Volume 2, pp. 125-134.

- Wikar, Z.; Ciechanowski, M. Ssaki rezerwatu przyrody „Studnica” i jego otoczenia. Chrońmy Przyrodę Ojczystą 2019, Volume 75(5), pp. 374 – 387.

- Ciechanowski, M.; Przesmycka, A.; Sachanowicz, K. 2006. Nietoperze (Chiroptera) Wdzydzkiego Parku Krajobrazowego. Parki Narodowe i Rezerwaty Przyrody 2006, Volume 25(4), pp. 85 – 100.

- Apoznański, G.; Kokurewicz, T.; Błesznowska, J.; Kwasiborska, E.; Marszałek, T.; Górska, M. Use of Coniferous Plantations by Bats in Western Poland During Summer Months”. Baltic Forestry 2020, Volume 26, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowski, M. Ssaki (Mammalia). In Przyroda rezerwatów Kurze Grzędy i Staniszewskie Błoto na Pojezierzu Kaszubskim; Herbich, J., Ciechanowski, M., Eds.; Fundacja Rozwoju Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego, Gdańsk, Poland, 2009; pp. 256-264.

- Jarzembowski, T.; Ostrach-Kowalska, A.; Rymarzak, G. Chiropterofauna Kaszubskiego Parku Krajobrazowego. Przegląd przyrodniczy 1997, Volume 8(3), pp. 123-127.

- Ciechanowski, M. Ssaki (Mammalia). In Przyroda projektowanego rezerwatu "Dolina Mirachowskiej Strugi" na Pojezierzu Kaszubskim; Ciechanowski, M., Fałtynowicz, W., Zieliński S.; Eds.; Acta Botanica Cassubica; Gdańsk, Poland, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 110-121.

- Wojtaszyn, G. Nietoperze Pojezierza Wałeckiego. Przegląd przyrodniczy 2002, Volume 13(1-2), pp. 199-211.

- Lesiński, G.; Gryz, J.; Rachwald, A.; Krauze-Gryz, D. Bat assemblages in fragmented forest complexes near Rogów (central Poland). Forest Research Papers 2019, Volume 79, pp. 253-260. [CrossRef]

- Górecki, M.T. Nietoperze Chiroptera okolic Skierniewic. Przegląd przyrodniczy 1998, Volume IX(3), pp. 101 – 108.

- Lesiński, G.; Hejduk, J.; Gajęcka, K.; Górecki, M.; Janus, K.; Zieleniak, A. Nietoperze Bolimowskiego Parku Krajobrazowego i terenów otaczających. Parki Narodowe i Rezerwaty Przyrody 2018, Volume 37, pp. 65-80.

| Taxon | Detectability coefficient |

|---|---|

| Myotis myotis | 1.25 |

| Small Myotis1 | 1.67 |

| Eptesicus serotinus | 0.63 |

| Pipistrellus spp. | 1.00 |

| Nyctalus noctula | 0.25 |

| Nyctalus leisleri | 0.31 |

| Plecotus auritus | 1.25 |

| Data | Habitat pair | Χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Lakes - glades | 1224.619 | <0.0001 |

| Lakes - gaps | 799.968 | <0.0001 | |

| Glades - gaps | 336.433 | <0.0001 | |

| Adjusted for detectability | Lakes - glades | 621.029 | <0.0001 |

| Lakes - gaps | 574.69 | <0.0001 | |

| Glades - gaps | 159.295 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).