Introduction

Characterization of farm animal include all activities related to the identification, quantitative and qualitative description, and recording of breed populations and the natural habitats and studying production systems, moreover, phenotypic characterization is used to rank animal population according to their levels of phylogenetic distinction (FAO 1984) (FAO 2012).

During early colonization of the South American continent, domestic livestock from Europe slowly spread out through in a remarkable scenario of climate and cultural diversification. This phenomenon began in the sixteenth century, where several European livestock breeds were challenged to adapt and breed for the purpose of land use and food supply (Chirinos et al. 2011). Such scenario configures the context in which today several bovine breeds roam along the Central American landscape. Some groups were formed mainly by natural selection, thus being logical to suppose they formed geographically differentiated groups.

Guatemala livestock production is at present yet constituted by smallholder farmers in traditional agropastoral production systems, dealing primarily with animals of local origin and not characterized as belonging to “improved” breeds. In recent years, some livestock projects aimed at increasing the knowledge of indigenous breeds have been undertaken in Guatemala and some local populations have been characterized based on their phenotypic constitution, for instance, “Barroso-Salmeco” (Jáuregui et al. 2014). But the mere description is not enough for the rational utilization of the local animal genetic resources available, or for conservation purposes.

Ecotypes must be understood as different phenotypes due to adaptation to different ecological conditions, e.g. “ecotypes” (FAO 2010) (Phanor Manrique 1997), such among “Rubia Gallega” (Galician Blond), from N Spain (“Mountain” and “Valley” ecotypes) (Legide and Ceular 1994). Multivariate discriminant analyses of morphological traits can be effective for a precise and objective discrimination of ecotypes if geographically separated populations do exist. This triggered our interest to conduct this research work to characterize possible morphological differences of “Paisanita” cattle depending on description of morphometric measurements.

Material and methods

Area of Study

The present work was conducted in the natural origin area of this population in Ch’ortí area, Chiquimula Department, NE Guatemala. Sampling was performed in 4 different municipalities: Jocotán (14°49′00″-89°23′00), Camotán (14°49´13”-89°22´24”), San Juan Ermita (14°45´37”- 89°25´50”) and Olopa (14°41´25”-89°21´00”), which represented two thermal or climatic floors. For Jocotán and Camotán altitude is 400 to 1200 mt above mean sea level (mamsl), with a mean annual temperature and rainfall range from 19 to 24º C, and from 500 mm to 1000 mm, respectively. They are covered by subtropical temperate rainforest and dry forest, and thorn bush. For San Juan de la Ermita and Olopa, altitude is 650 to 1700 mamsl, and a mean annual temperature and rainfall from 20 to 26º C, and from 1000 mm to 1349 mm, respectively. They are covered by subtropical dry and subtropical temperate rain forests.

Farm Sampling

The sampling frame was established following previous surveys to the region aimed to identify villages where pure animals can be found and where were it was not used other cattle breeds. In these sites, animals were raised on fenced natural pastures, grazing day and night or herded by day and kept in pens at night.

Data collection

A total of 47 adult females was measured and included in this study, distributed among fours studied areas [Jocotán (n=4), Camotán (n=9), San Juan Ermita (n=14) and Olopa (n=20)]. They age maturity was ascertained by the visual examination of their dentition (possession of at least three pairs of permanent teeth). Body measurements were carried out using a measuring stick and a measuring tape on animals standing on a level surface and maintained in upright posture in an unforced position. Body measurements were determined as reported by literature (Lomillos and Alonso 2020):

Withers height (ALC): the vertical distance from the floor beneath the animal to the point of the withers (Regio interscpaularis).

Hip heigth (ALG): the distance down to the hips (Tuber coxae) from the distance down to the floor.

Skull length (LCR): the distance from the nucha (Protuberantia intercornualis) to the virtual fronto-nasal point.

Head length (LCB): the distance from between the nucha (Protuberantia intercornualis) to the distal end of the muzzle (Regio naris).

Face length (LCN): the distance from the virtual frontal bone to the distal end of the muzzle (Regio naris).

Skull width (ACR): measured as the widest part of frontal bone (Os frontale).

Head width (ACB): the distance between facial tuberosities (Tuber faciale).

Face width (ACN): the widest part of the infraorbital region (Regio infraorbitalis).

Horn length (LA): the distance from the tip to the base of the horn.

Chest perimeter (PT): the narrowest circumference immediately posterior to the forelegs.

Chest depth (DD): the distance between the top behind the scapular and the flow of the sternum (taken to be the depth of brisket) immediately behind forelegs.

Chest width (DB): the widest part of the thorax (Regio costalis).

Abdominal perimeter (LA): the belly circumference at the level of navel (Regio abdominis lateralis).

Body perimeter (DL): the distance from shoulder joint (Regio articulationis humeri) to hip joint (Regio articulationis coxae).

Body length (LC): the distance on the dorsal midline from the top of the head to pin bones (Tuber ischii).

Forelimb length (LMA): the distance from most dorsal point of scapulas to shoulder joint, from shoulder joint to elbow joint, and from elbow joint to hoof.

Hindlimb length (LMP): the distance from hip joint to knee, from knee to hock, and from hock to hoof.

Forelimb cannon circumference (PCA): the narrowest circumference of the fore-cannon bone (Regio metacarpi).

Hindlimb cannon circumference (PCP): the narrowest circumference of the hind-cannon bone (Regio metatarsi).

Rump length (LG): the distance from hips (Tuber coxae) to pins (Tuber ischii).

Rump width (AG): the distance between hips (Tuber coxae).

Inter-iliach width (AII): the distance between pin bones (Tuber ischii).

Hair length (LPl): length of hair on the back.

Body weight (PV).

Ethical statement

The study involved taking body measurements from cattle with the consent and in the presence of owners who agreed to be involved in the project.

Statistical analysis

First, a Non-Parametric Multivariate Analysis of Variance (NPMANOVA) using correlation distances was used to assess differences between areas. The most discriminant variables were then selected through a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) from correlation matrix. PCA allowed the reduction of the dimensionality of a dataset, while preserving as much “variability” (i.e. statistical information) as possible (Jollife and Cadima 2016). Canonical Correspondence (CC) distributed individual animals in a two-axis plot. Collected data was analysed using PAST v. 2.17c (Hammer, Harper, and Ryan 2001), with a 95% confidence level.

Results

Main descriptive statistics are shown in

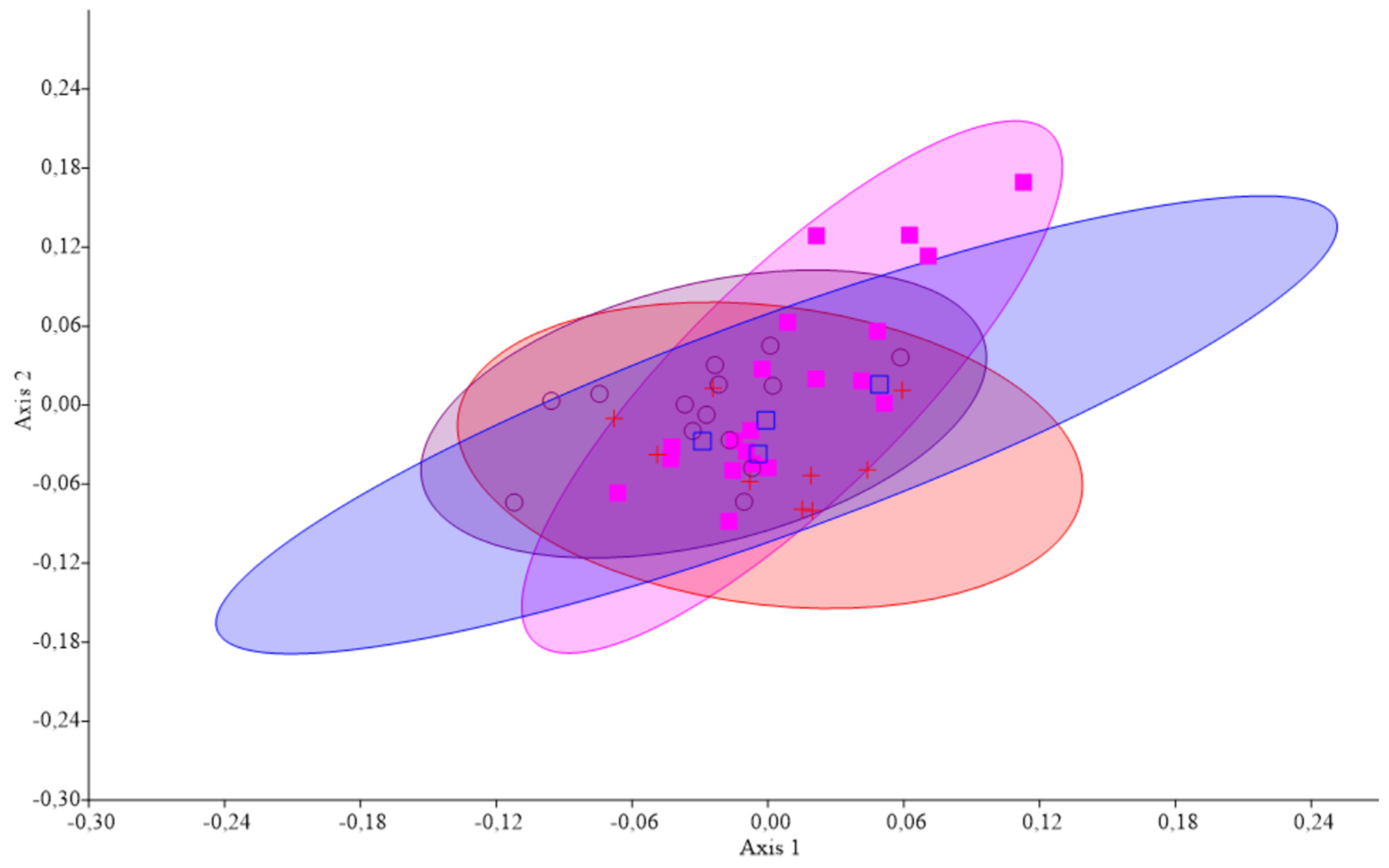

Table 1. CV ranged from 6.9% to 27.4%, with only PV, LPl and LA with values >20%. NPMANOVA reflected no statistical differences between areas. In PCA, three first Principal Components (PC) summarized the total observed variance (PCA+PC2+PC3 = 64.75%+23.61%+11.62%). In CC plot, individual animals (as seen in

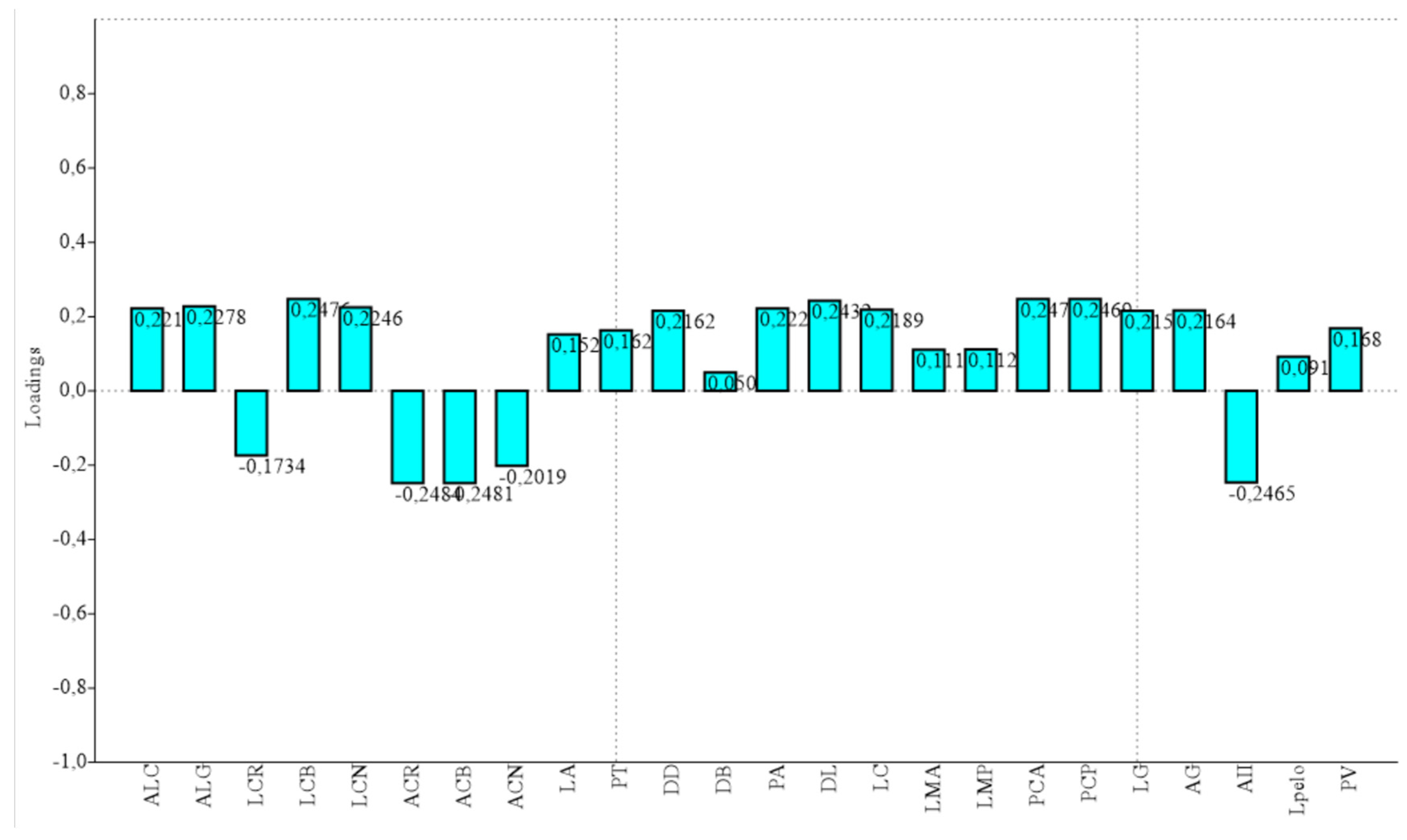

Figure 1) showed that no group were clustered together. Variables presented similar loadings (

Figure 2), although some positive and other negative, thus not being representative of general size (Jollife and Cadima 2016).

Discussion

Since recent years, there has been a consistent increase in the interest on Guatemala livestock breeds. However, for some specific and isolated populations, such as “Paisanita” cattle, little or no conservation initiatives have been proposed. Consequently, this research can be interpreted as a proposal aimed at the conservation of this naturally selected breed in Guatemala. First conclusion is that values dispersions (CV) was relatively low, thus indicating a rather uniform population or, in other words, a true “breed”. "Ecotype" refers to a locally adapted population assumed to be a result of the action of natural selection. Ecotypes are not genetically distinct from the rest of the breed, only morphologically for adaptative traits. Our data do not reflect differentiated populations -e.g. no different morphostructures among different geographical groups-, which could be interpreted as possible ecotypes due to ecological differences among sampled areas.

Rational selection criteria/breeding goal traits, development objectives and strategies should be developed for each subpopulation for their sustainable breeding, utilization and conservation. Appropriate choices can be made for the conservation of genetic material if ecotypes are not detected. Results found in this work are of great interest to the breed, because despite its reduced census, we observe that the existing nuclei do not exhibit great morphological variation between individuals and therefore remain within a possible racial pattern. New researches may be centred to evaluate the level of divergence among neighbour local breeds. In any case, the authors strongly recommend the formulation of policies to promote the use of these indigenous animals in breeding programmes rather than the usual practice of cross-breeding with exotic genotypes.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their deep gratitude to “Paisanita” cattle owners. We also want to acknowledge the anonymous.

Conflict of interests

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Chirinos, Z. et al. 2011. “Caracterizacion Del Dimorfismo Sexual En Ganado Criollo Limonero Mediante Medidas Corporales.” Rev. Fac. Agron. (UCV) 28(1): 554–64.

- FAO. 1984. Animal genetic resources conservation by management, data banks and training Animal Genetic Resources Conservation by Management, Data Banks and Training. Rome: FAO and UNEP.

- ———. 2010. “Parte 4. Estado de La Cuestión En La Gestión de Los Recursos Zoogenéticos.” In LA SITUACIÓN DE LOS RECURSOS ZOOGENÉTICOS MUNDIALES PARA LA ALIMENTACIÓN Y LA AGRICULTURA, ed. FAO. Roma, 369–77.

- ———. 2012. 11 FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines Phenotypic Characterization of Animal Genetic Resources. Rome.

- Hammer, Ø., D.A.T. Harper, and P.D. Ryan. 2001. “PAST v. 2.17c.” Palaeontologia Electronica 4(1): 1–229.

- Jáuregui, J., C. Gutiérrez, C. Cordón, and L. Vásquez. 2014. “Determinación Morfoestructural Del Bovino Criollo Barroso Salmeco En Guatemala.” Actas Iberoamericanas de Conservación Animal 4: 6–8.

- Jollife, I.T., and J. Cadima. 2016. “Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 374(2065): 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Legide, M., and A. Ceular. 1994. “La Raza Rubia Gallega Ecotipo de Montaña.” Animal Genetic Resources 14: 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Lomillos, J.M., and M.E. Alonso. 2020. “Morphometric Characterization of the Lidia Cattle Breed.” Animals 10(1180): 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Phanor Manrique, L. 1997. “El Ecotipo, Criterio Para Medir Adaptabilidad Bovina En Condiciones Climáticas Tropicales: Comportamiento Productivo En Una Raza Lechera.” Acta Agronómica 47(1): 45–48.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).