1. Introduction

Addressing hearing loss and effectively managing it with hearing aids are vital for improving the quality of life for individuals with hearing impairments. This is especially crucial in cases of severe hearing loss, where the impact on speech comprehension is significantly heightened. A particularly interesting aspect within this field is the variation in speech comprehension among a specific subgroup of individuals characterised by four-frequency pure-tone average (4FPTA) values ranging from 60 to 80 dB HL, as recent studies have shown [

1,

2,

3,

4]. It is important to note that this variability in speech comprehension persists even in the presence of adequate hearing aid (HA) intervention. The variability was found with respect to two measures: (i) the 4FPTA and (ii) the difference between the maximum word-recognition score, WRS

max, and the aided score, WRS

65(HA), at conversational level [

3,

5,

6,

7]. First concepts to address the discrepancy between WRS and pure-tone thresholds were introduced by Carhart [

8]: for word recognition in quiet this was referred to as “loss of acuity”, and a second component caused by impaired processing of the audible speech signal was referred to as “loss of clarity”. Plomp [

9] named these components of hearing loss “attenuation” (class A) and “distortion” (class D). Attenuation can be quantified by pure-tone audiometry. The distortion component characterises the negative impact of reduced temporal and frequency resolution. Furthermore, Plomp [

9] stated, that the distortion component has a detrimental effect on WRS in quiet as well. Consequently, the distortion component explains the deterioration in speech comprehension that is not expressed by attenuation (4FPTA).

The term “distortion” can be applied to denote individuals who exhibit deficient speech comprehension within the above-mentioned subgroup (persons with 60–80 dB HL 4FPTA). These deficits are thought to have their root causes in disturbed temporal processing and limited frequency resolution of the auditory periphery. A plausible explanatory framework for this phenomenon involves the notion of perceptual decay. In such instances, the perception of loudness diminishes over a brief period, despite consistent sound-level presentation. The tone decay test (TDT), introduced by Carhart [

10], entails the presentation of a continuous tone at 5 dB SL (sensation level), with successive increments in intensity until a stable perceptual threshold is achieved. The cumulative increase in intensity resulting from this procedure is termed tone decay (TD).

Abnormal TD may be inferred when attenuation exceeds the threshold of 15 dB. Huss

et al. [

11] found that abnormal TD becomes more prevalent when hearing loss exceeds 50 dB HL. Importantly, TD is not manifested uniformly across all frequencies and intensities; rather, it is particularly pronounced at higher frequencies compared with lower ones. A decline in loudness perception, known as loudness adaptation, can also occur at higher sound levels, although with less prominence in comparison with stimuli near the perceptual threshold.

The underlying physiological cause of TD has yet to be definitively elucidated. However, the initial observation that low levels and high frequencies are more susceptible to TD led to the formulation of the “restricted pattern” hypothesis [

12,

13]. This hypothesis suggests that for tones with minimal sensation levels or frequencies that stimulate the basal end of the cochlea, the spatial excitation pattern on the basilar membrane evoked by continuous tones is highly confined. Nonetheless, Wynne

et al. [

14] posit that TD can be attributed either to direct damage to inner hair cells or to the auditory nerve. Their findings suggest that TD at low frequencies arises from disruptions in ribbon synapses, while high-frequency TD is more likely to be associated with auditory nerve disruptions. Nevertheless, a consensus seems to be forming that either inner hair cells or retrocochlear structures are involved in the TD phenomenon.

As TD increases, a corresponding decline in both unaided and aided speech recognition can be expected. However, it remains unclear to what extent this decrease can be solely attributed to perceptual decay. Furthermore, it is unclear whether this effect persists even after the provision of an HA and, if so, which frequency range is particularly susceptible to heightened challenges in speech comprehension.

To our knowledge, up to now, there has been no investigation of TD in order to explain the variability of WRSmax and WRS65(HA) beyond the impact of 4FPTA. This study was therefore undertaken to investigate a patient cohort characterised by hearing loss (4FPTA) ranging from 50 to 80 dB HL, and, after completion of measurements and discharge of the patient, to compare TD with unaided and aided word-recognition scores.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Characteristics

Twenty-two patients were included in this prospective study: 10 males, 12 females. Their mean age was 67.6 years, ranging from 37 to 88 years. Five subjects had both ears included in this study resulting in a total of 12 left ears and 15 right ears. The patients visited the clinic for one of two reasons: They were recruited in one of the local hearing-aid shops, or they visited our clinic for HA evaluation between November 2021 and June 2023.

2.2. Audiological Parameters

All participants underwent audiometric tests in both ears using a clinically calibrated audiometer (AT900, Auritec GmbH Hamburg, Germany). Pure tones were presented at frequencies of 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz through a headphone (DT48; Beyer, Heilbronn, Germany). Subsequently, speech recognition was evaluated by measuring the word-recognition score (WRS). In the unaided condition, different sound levels were presented, also through the headphone, to find the highest word-recognition score (WRSmax). The aided word-recognition score, WRS65(HA), was measured in quiet unilaterally at a presentation level of 65 dB sound pressure level (SPL) in free field. The contralateral ear was masked appropriately. The speech-test signal (Freiburg Monosyllable Test) was presented frontally in a soundproof room (1×2×44 m).

2.3. Tone Decay Test

For the tone decay test (TDT) [

10] the AT900 audiometer was used according to routine procedures, as follows. Before TD testing, an audiogram is obtained. The patient is then familiarised with the TDT measurement procedure: “You will hear a very soft sound. Press the button as soon as the sound is no longer audible.” [

16].

The TDT is then performed for the frequencies 1, 1.5, 2, 3 and 4 kHz, if possible. At each frequency, a starting level is chosen, set to 5 dB above the threshold found in the audiogram. The test begins with the presentation of a continuous tone at the start level, and the patient confirms briefly that this level is audible. When the patient presses the button to indicate that the tone is no longer audible, the procedure is repeated, with the start level increased by 5 dB. The test ends when the patient continues to report audibility for at least 60 seconds, or when the maximum permissible volume of 110 dB has been reached. The difference between the starting level and the resulting level at the end of this procedure is referenced as TD.

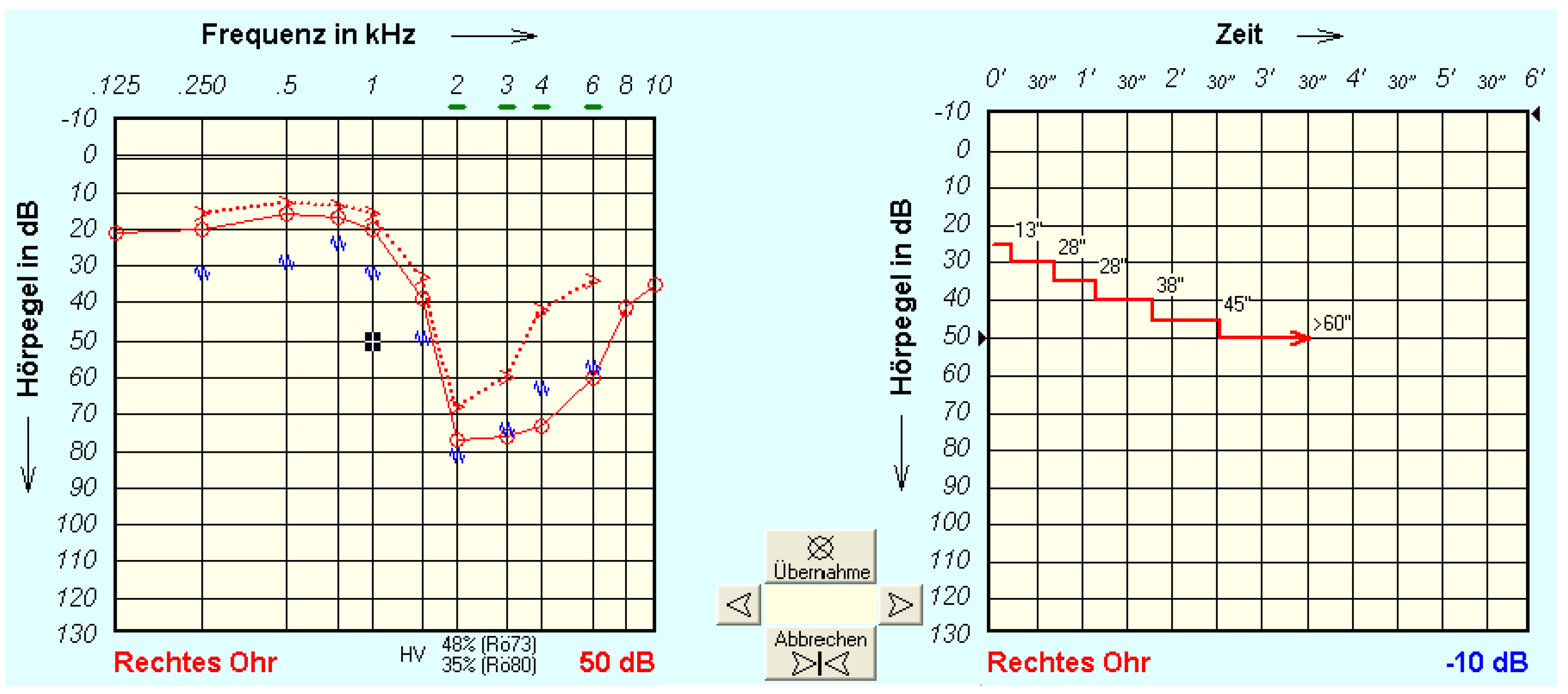

Figure 1 shows an example of measurement in a study participant (right ear) with a very strong tone decay. The left-hand panel (A) shows the pure-tone hearing loss (air and bone conduction together with the contralateral masking noise). The right-hand panel (B) shows the tone decay, here for 1 kHz, over time. In this example the last presentation level heard for at least 60 s was 50 dB, and the TD at 1 kHz was 25 dB.

The performance of the test is limited by the degree of hearing loss due to the 110 dB level limitation and, in the case of asymmetrical hearing loss, by the side-difference of the threshold as determined by the audiometry conducted before the test (>40 dB was considered excessive). This is because the test involving active masking of the contralateral ear is likely to be less reliable. In addition, with high hearing loss, the auditory fatigue is not always maximally detectable due to the level limitation. This sealing effect must be taken into account when interpreting the results. If tinnitus is present, the test cannot be performed for the frequencies affected.

The single exclusion criterion was single-sided deafness according to the definition given by Arndt

et al. [

17].

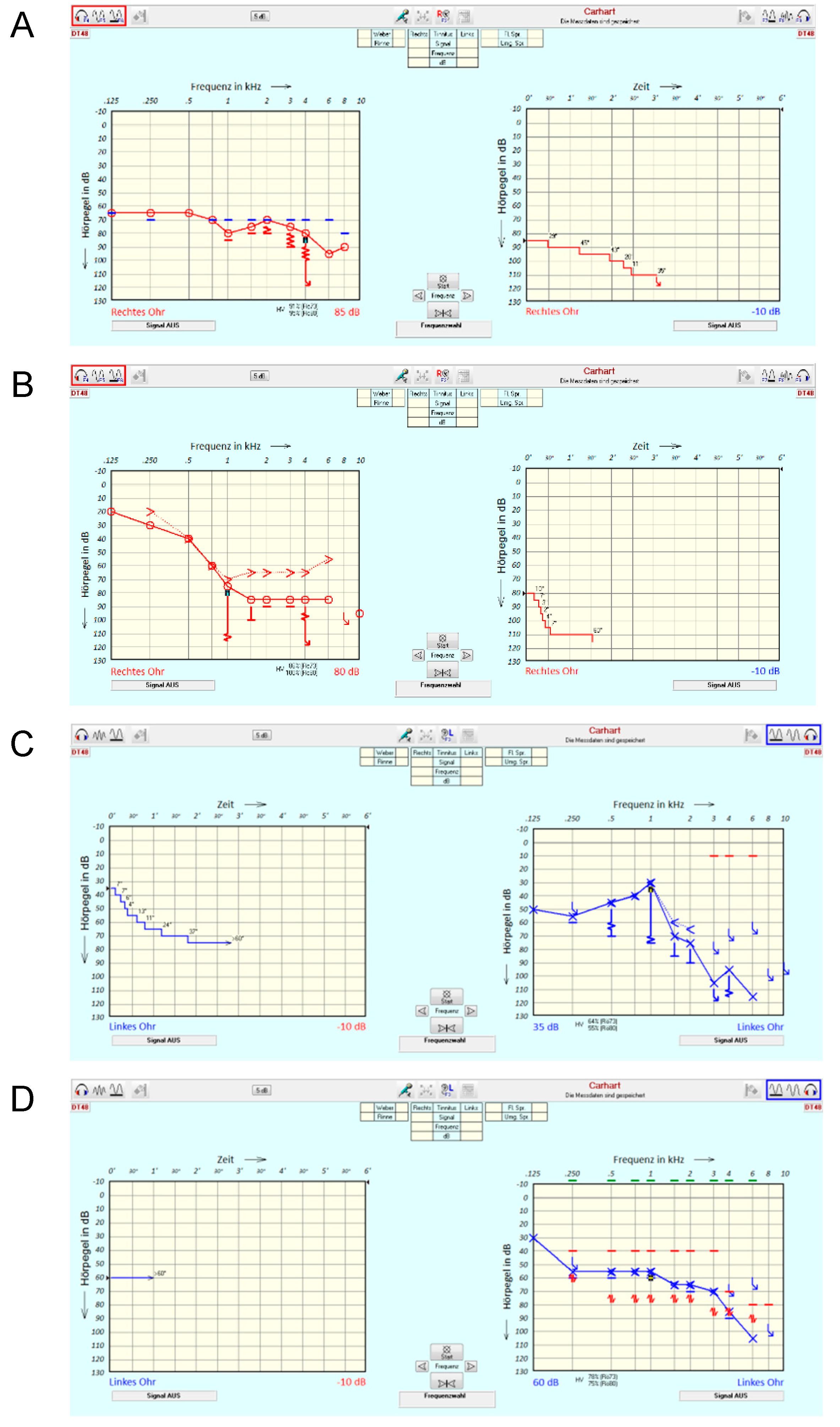

2.4. Possible Characteristics of Tone Decay Measurements

Figure 2 illustrates a selection of possible characteristics of TD measurements. It underlines the degree to which all the information contained in the TDT is reduced in this first feasibility study, where only the final extent of TD [dB] is evaluated. In case example A, a patient (right ear) with pantonal hearing loss of 4FPTA = 74 dB is presented. The TD at 4 kHz is apparently larger than the audiometer limits allow for measurement. In this case, the TDT yields 25 dB, thereby underestimating the impact of disturbed processing on tone perception. Case example B shows a patient (right ear) with a steep sloping audiogram and a TD of 30 dB. A special characteristic of this case is the rapid speed of threshold deterioration. Case example C (left ear) shows that this kind of rapid decline is not necessarily connected to a threshold of 75 dB as in case example B but may already be apparent at a threshold of 30 dB. Finally, case example D shows a patient (left ear) with a moderate sloping audiogram without any TD.

3. Results

Demographic and audiometric data for the study patients are displayed in

Table 1.

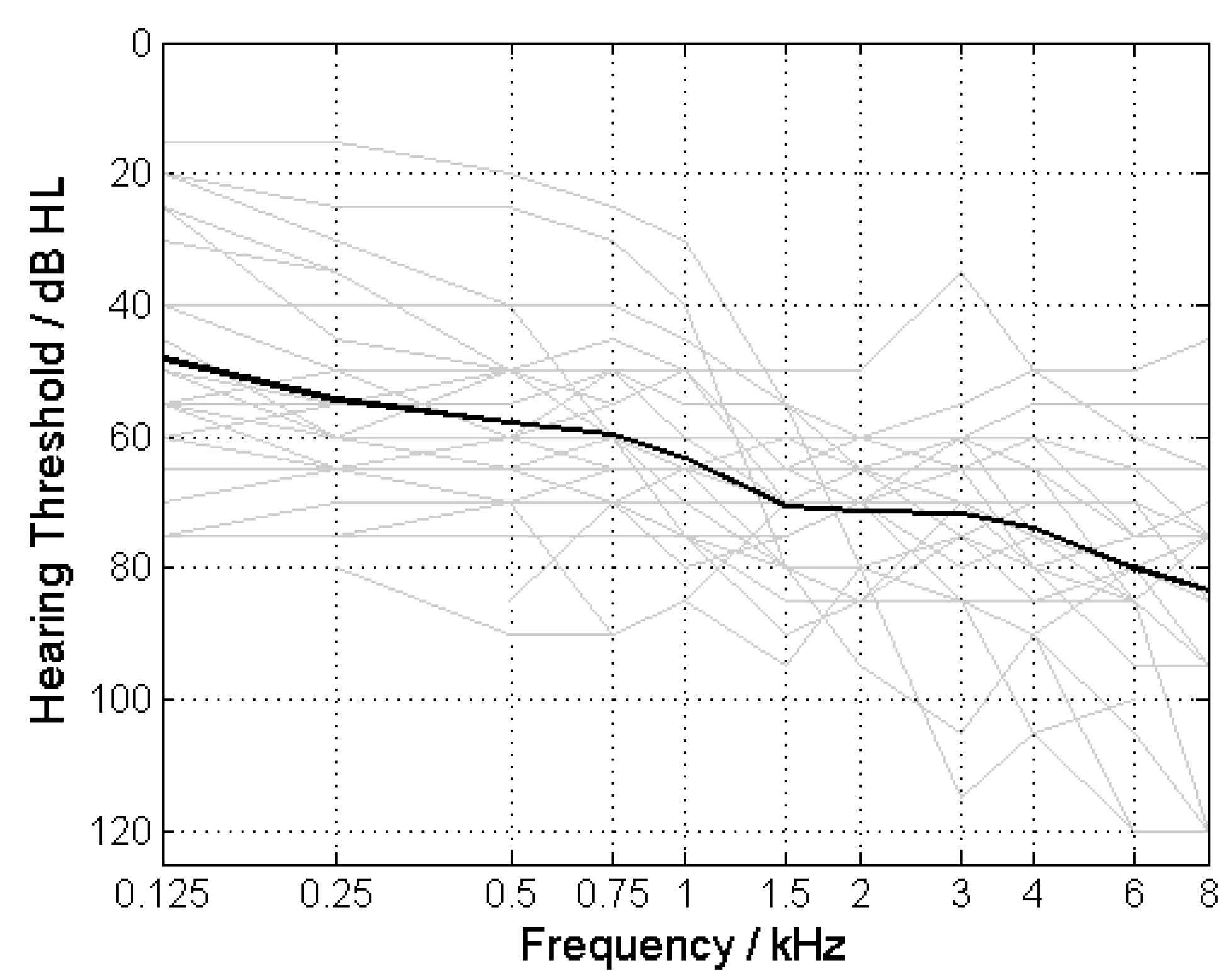

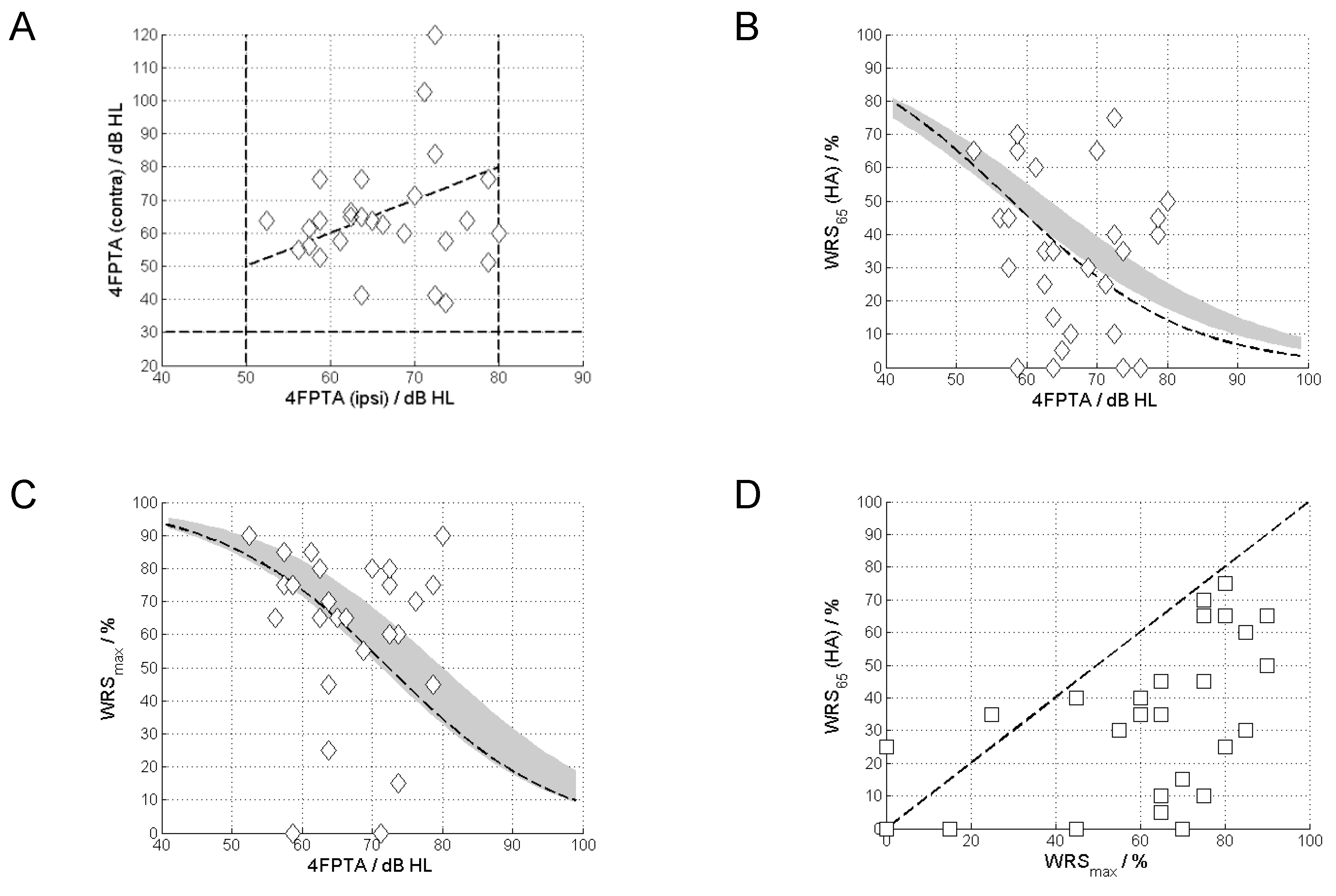

3.1. Pure-Tone and Speech Audiometry

All ears had a 4FPTA between 50 and 80 dB HL with an average 4FPTA of 66.6 ± 7.7 dB HL (mean ± standard deviation;

Figure 1). A 4FPTA of at least 30 dB HL was present in the contralateral ear, with an average of 65 ± 17.2 dB HL (

Figure 2a). The word-recognition score at 65 dB with an HA (WRS

65(HA)) was 34.1% ± 23.5% (

Figure 2b), whereas the maximum word-recognition score (WRS

max) was 61.9% ± 25.2% (

Figure 2c). In almost all cases the WRS

65(HA) was below the WRS

max (

Figure 2d).

Figure 3 shows the pure-tone thresholds for the ears included in the study. According to the inclusion criteria the 4FPTA ranged from 50 to 80 dB.

Figure 4A shows the relationship between the 4FPTAs of the ipsilateral (included case) and contralateral ears. The vast majority (XX/YY) of cases shows asymmetric 4FPTAs of up to 70 dB.

Figure 4B shows the WRS

65(HA) vs the 4FPTA. The majority (24) of cases exhibits a WRS

65(HA) below the WRS

max. Despite the narrow inclusion 4PTFA inclusion band (50 to 80 dB HL) we see a highly variable WRS

max, from 0 to 90%, with a variability of the aided scores from 0 to 75% (

Figure 4C).

Figure 4D shows the relationship between WRS

65(HA) and WRS

max. For the majority of cases (24/27) the WRS

65(HA) did not reach the WRS

max.

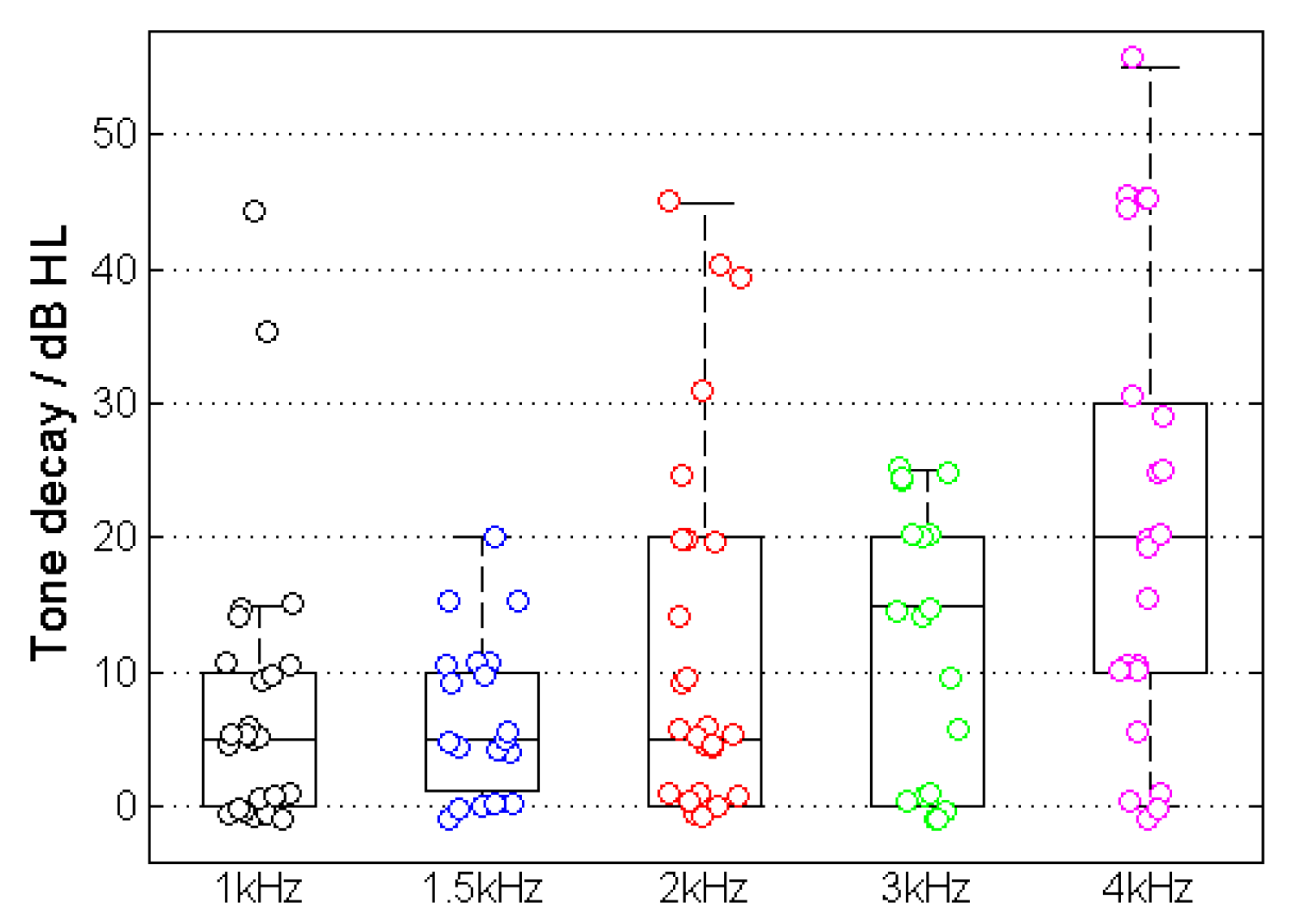

3.2. Tone Decay

Figure 5 shows the results of the TD measurement for the example in

Figure 1. The majority of cases showed a TD with higher incidence and amplitude at higher frequencies. The measured TD increased at higher frequencies and resulted in TD

1kHz = 8.0 ± 10.6 dB, TD

1.5kHz = 6.8 ± 5.8 dB, TD

2kHz = 12.4 ± 14.0 dB, TD

3kHz = 12.2 ± 10.3 dB and TD

4kHz = 21.1 ± 17.2 dB.

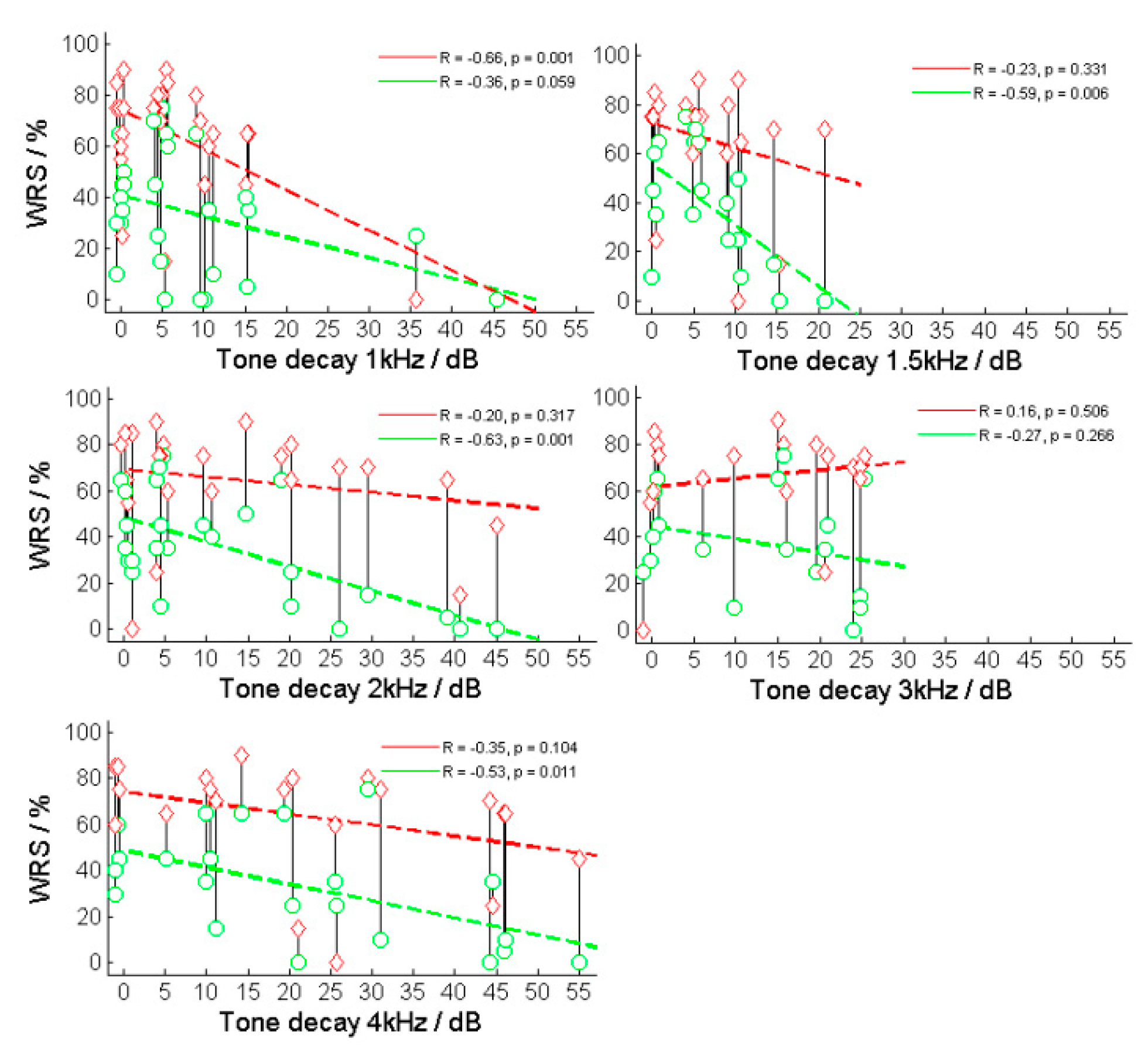

The correlations between the TDs for each frequency and the speech recognition for both WRS

65 (HA) and WRS

max were investigated. Significant correlations were found at WRS

65 (HA) and TD

1.5kHz (R = –0.60, p < 0.01) and

TD2kHz (R = –0.63, p < 0.001) (

Figure 5) as well as WRS

max and TD

1kHz (R = –0.66, p < 0.001). The same result was obtained from the frequency-specific comparison after the subjects had been grouped into normal and abnormal TD, resulting in WRS

65 (HA) and

TD1.5kHz (p = 0.005) and

TD2kHz (p = 0.006) as well as WRS

max and

TD1kHz (p = 0.006).

Figure 5.

Relation between maximum and aided word-recognition scores (WRSmax and WRS65(HA)) and tone decay (TD) at different frequencies. The red symbols and lines correspond to the relationship between TD and WRSmax, while the green line corresponds to the relationship between TD and WRS65(HA).

Figure 5.

Relation between maximum and aided word-recognition scores (WRSmax and WRS65(HA)) and tone decay (TD) at different frequencies. The red symbols and lines correspond to the relationship between TD and WRSmax, while the green line corresponds to the relationship between TD and WRS65(HA).

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the two WRS (WRS

max and WRS

65(HA)) and the TD for various test frequencies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Tone Decay and Speech Comprehension

In this study, we explored the relationship between speech comprehension in individuals with moderately severe to severe hearing loss (4FPTA = 50–80 dB HL) and tone decay within the frequency range 1–4 kHz. Our hypothesis posits that a portion of the considerable variability in speech comprehension within this threshold range for hearing loss could be elucidated by factors such as tone decay (TD). The large variability, 90 percentage points for WRS

max and 75 percentage points for WRS

65(HA) in the inclusion range for this study (50–80 dB HL), correspond to previously reported WRSs in larger population of HA users [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

18,

19]. This applies also to the difference between maximum and aided WRSs. We conclude that the results of our study are applicable to the population of hearing-aid users typical for an ENT department of a maximum-care hospital with a cochlear implant program.

The key finding of this study is the negative correlation between TD and speech comprehension. A consistent trend is evident across all frequencies, with the 1–2 kHz range demonstrating the most clearly significant correlation. This finding aligns with expectations, considering the critical importance of this frequency range for speech comprehension. Moreover, our investigation may indicate that the impact of TD on speech comprehension is more pronounced when using HAs compared with situations without them in the frequency range between 1.5 and 3 kHz. Notably, during the unaided speech comprehension test, we examined WRSmax, at levels typically reaching the discomfort level, whereas in the aided test, speech was assessed at 65 dB SPL in free field. In cases with unstable thresholds or tone decay, the fitting of the HA to the threshold becomes imprecise, resulting in inaccurate assumptions for frequency-specific amplification in the presence of TD. Additionally, TD occurs more rapidly with an active HA, as it consistently stimulates close to the threshold. In contrast, WRSmax appears more resilient against TD, possibly owing to the consideration of several levels within the measurement paradigm.

This outcome highlights the constraints of traditional approaches to HA programming when confronted with TD, shedding light on why this particular patient group may no longer be deemed suitable for HA fitting and might be more inclined toward consideration for cochlear implant (CI) fitting. Nevertheless, exploring alternative fitting strategies that take TD into account is a plausible avenue. Such strategies would require the recalibration of thresholds and corresponding amplification, tailored to the frequency-specific challenges posed by TD. To achieve this, the frequency- and level-specific temporal trajectory of TD would need to be recorded individually, coupled with an understanding of possible threshold recovery processes.

4.2. Application of Tone Decay Assessment in a Changing Patient Population

One important aspect of HA evaluation in our clinic is the assessment of cochlear implant (CI) candidacy. The most recent German CI guidelines [

20] support CI implantation up to WRS

65(HA) ≤ 60% regardless of pure-tone thresholds. This has led in the past decade to a growing number of CI candidates among cases with considerable aided WRS [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Together with a higher preoperative WRS

65(HA) this also extends CI provisions also to some patients with 4FPTA of 50 dB HL [

21,

22,

23,

24]. These patient characteristics would allow improved differential preoperative diagnosis in CI candidates with good 4FPTA and poor WRS. Since some of these diagnostic tests for CI (of which TDT is one example) require a sufficient amount of residual hearing, TDT may offer a chance – and may meet the clinical need – to explain the variability of WRS

65(HA). Additionally, the nature of poor performance in a CI-fitted population is not yet understood [

25]. For example, recent studies [

26,

27,

28] has have devoted considerable effort to showing that various factors – including genetic disposition, aetiology, and comorbidities – have an effect on CI outcome. Furthermore, the preoperative audiometric assessment in clinical routine [

20] potentially provides prognostic value [

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, we see still an urgent need for further improvement of the preoperative audiometric assessment. Supra-threshold diagnostic tests, such as TDT and other measurements, as earlier applied for topodiagnostics [

29,

30] in the presence of less sophisticated imaging resources could experience a renaissance in the preoperative assessment of CI candidates. Retrocochlear lesions can be ruled out by modern imaging, which is superior to audiometry for this purpose [

31]. Other retrocochlear deficits can be quantified by re-application of established supra-threshold tests and available objective measures [

25,

32,

33]. In the long term it might be possible to determine a correlation between these additional preoperative diagnostic results and speech recognition with a CI. A clustering according to the different patient characteristics may help to solve the enigma of poor performance [

25]. If the preoperative TD also partially explains the variability in word recognition with CI, then it should be included in future studies. In the past, TDTs have already been performed in CI recipients [

34,

35]. Wable

et al. [

34] concluded that TD might facilitate further study of condition of the auditory system in CI recipients, to follow up possible retrocochlear damage and to link TD to neural survival. Wasman

et al. [

35] highlighted the potential use of TDT to explain the spread of outcome in CI recipients but, because of the small number of study participants, they did not draw clear conclusions. It appears that, together with TD in CI recipients, the preoperative assessment of TD can contribute to a better understanding of the above relationships.

4.3. Limits of the Study and Feasibility

The assessment of TD was basically feasible in our study population. However, the TD assessment took up to 1.5 hours. The procedure was perceived as demanding by some of the more elderly study participants. In our experience, some patients may require a more extensive introduction to the test procedure as well as a training run. Furthermore, before the TDT a precise determination of audiometric thresholds is required; this too can be a challenging task for some patients. Some recipients had difficulties in listening to pure-tone presentations for longer periods. Additionally, tinnitus can be expected to have a detrimental influence on the precision of TDT. For some patients the perception of the (pure) test tone may change into a noise-like perception, which can be considered as a symptom of possible neural pathologies [

16]. Finally, in some patients two ceiling effects potentially limit the diagnostic value. The first refers to the ceiling of the speech test, while the second may occur in cases where 4FPTA is already poor and the full impact of TD cannot be assessed owing to audiometer limits or the fact that an uncomfortable presentation level has already been reached. To follow up on the results reported here we plan to continue the study, both in order to increase the robustness of the result with more patients and in order to allow additional measurements to be included.

5. Conclusions

The tone decay test is a feasible method for determining tone decay and may contribute to explaining the variability of word-recognition scores in hearing-aid users with hearing loss in the range 50–80 dB. It may provide a better understanding of the limits of hearing-aid use in patients considered for cochlear implantation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, FS, WG, RM; methodology, FS; software, FS; validation and formal analysis, FS; investigation, FS; resources, FS; data curation, FS; writing—original draft preparation, FS, TH; writing—review and editing, FS, TH, LZ, WG, RM; visualisation, FS; supervision, RM; project administration, RM, WG, FS; funding acquisition, RM, FS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Cochlear™ Research and Development Limited, grant number IIR-2347.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval by the Ethics Committee at University Medicine Rostock. Approval code: A 2021-0223 Approval date: 18 October 2021. This study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register under DRKS00032357,

https://www.drks.de/DRKS00032357 (last up-dated on 24 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

F.S., RM and WG received funding for other projects supported by different medical device companies. T.H. is employee of Cochlear Deutschland GmbH & Co.

References

- Hoppe, U.; Hast, A.; Hocke, T. Sprachverstehen mit Hörgeraten in Abhängigkeit vom Tongehör. HNO. 2014, 62, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, U.; Hocke, T.; Muller, A.; Hast, A. Speech Perception and Information-Carrying Capacity for Hearing Aid Users of Different Ages. Audiol Neurootol. 2016, 21 Suppl 1, 16-20. [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, C.; Hocke, T.; Hast, A.; Hoppe, U. Speech recognition with hearing aids for 10 standard audiograms : English version. Hno. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Engler, M.; Digeser, F.; Hoppe, U. [Effectiveness of hearing aid provision for severe hearing loss]. Hno. 2022, 70, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRackan, T.R.; Ahlstrom, J.B.; Clinkscales, W.B.; Meyer, T.A.; Dubno, J.R. Clinical Implications of Word Recognition Differences in Earphone and Aided Conditions. Otol Neurotol. 2016, 37, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRackan, T.R.; Fabie, J.E.; Burton, J.A.; Munawar, S.; Holcomb, M.A.; Dubno, J.R. Earphone and Aided Word Recognition Differences in Cochlear Implant Candidates. Otol Neurotol. 2018, 39, e543–e549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franks, Z.G.; Jacob, A. The speech perception gap in cochlear implant patients. Cochlear Implants Int. 2019, 20, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carhart, R. Basic principles of speech audiometry. Acta Otolaryngol. 1951, 40, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plomp, R. Auditory handicap of hearing impairment and the limited benefit of hearing aids. J Acoust Soc Am. 1978, 63, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carhart, R. Clinical determination of abnormal auditory adaptation. AMA Arch Otolaryngol. 1957, 65, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huss, M.; Moore, B.C. Tone decay for hearing-impaired listeners with and without dead regions in the cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 2003, 114, 3283–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharf, B. Loudness adaptation. Hearing Research and Theory 1983, edited by J. V. Tobias and E. D. Schubert (Academic, New York), Vol. 2, pp. 1–56.

- Miśkiewicz, A.; Scharf, B.; Hellman, R.; Meiselman, C. Loudness adaptation at high frequencies. J Acoust Soc Am. 1993, 94, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynne, D.P.; Zeng, F.G.; Bhatt, S.; Michalewski, H.J.; Dimitrijevic, A.; Starr, A. Loudness adaptation accompanying ribbon synapse and auditory nerve disorders. Brain. 2013, 136, 1626–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, U.; Hast, A.; Hocke, T. Audiometry-Based Screening Procedure for Cochlear Implant Candidacy. Otol Neurotol. 2015, 36, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrowinski, D.; Scholz, G. Audiometrie Eine Anleitung für die praktische Hörprüfung., 5th ed.; Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; p. 58ff. ISBN 978-3-13-240107-5. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, S.; Laszig, R.; Aschendorff, A.; Hassepass, F.; Beck, R.; Wesarg, T. Cochlear implant treatment of patients with single-sided deafness or asymmetric hearing loss. HNO. 2017, 65, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronlachner, M.; Baumann, U.; Stover, T.; Weissgerber, T. [Investigation of the quality of hearing aid provision in seniors considering cognitive functions]. Laryngorhinootologie. 2018, 97, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beyer, A.; Rieck, J. H.; Mewes, A.; Dambon, J. A.; Hey, M. [Extended preoperative speech audiometric diagnostics for cochlear implant treatment]. Hno. 2023. [CrossRef]

- AWMF. Leitlinien: Cochlea-Implantat Versorgung und zentral-auditorische Implantate. 2020. Available online: https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/017-071l_S2k_Cochlea-Implantat-Versorgung-zentral-auditorische-Implantate_2020-12.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Hoppe, U.; Hocke, T.; Hast, A.; Iro, H. Cochlear Implantation in Candidates With Moderate-to-Severe Hearing Loss and Poor Speech Perception. Laryngoscope. 2021, 131, E940–e945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangavelu, K.; Nitzge, M.; Weiß, R. M.; Mueller-Mazzotta, J.; Stuck, B. A.; Reimann, K. Role of cochlear reserve in adults with cochlear implants following post-lingual hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rieck, J.H.; Beyer, A.; Mewes, A.; Caliebe, A.; Hey, M. Extended Preoperative Audiometry for Outcome Prediction and Risk Analysis in Patients Receiving Cochlear Implants. J Clin Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, U.; Hast, A.; Hocke, T. Validation of a predictive model for speech discrimination after cochlear impIant provision. Hno. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Moberly, A.C.; Bates, C.; Harris, M.S.; Pisoni, D.B. The Enigma of Poor Performance by Adults With Cochlear Implants. Otol Neurotol. 2016, 37, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudey, B.; Plant, K.; Kiral, I.; Jimeno-Yepes, A.; Swan, A.; Gambhir, M.; Büchner, A.; Kludt, E.; Eikelboom, R.H.; Sucher, C.; Gifford, R.H.; Rottier, R.; Anjomshoa, H. A MultiCenter Analysis of Factors Associated with Hearing Outcome for 2,735 Adults with Cochlear Implants. Trends Hear. 2021, 25, 23312165211037525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Pisa, J.; Hochman, J. Comorbidity associated with worse outcomes in a population of limited cochlear implant performers. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2023, 8, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropitzsch, A.; Schade-Mann, T.; Gamerdinger, P.; Dofek, S.; Schulte, B.; Schulze, M.; Fehr, S.; Biskup, S.; Haack, T. B.; Stöbe, P.; Heyd, A.; Harre, J.; Lesinski-Schiedat, A.; Büchner, A.; Lenarz, T.; Warnecke, A.; Müller, M.; Vona, B.; Dahlhoff, E.; Löwenheim, H.; Holderried, M. Variability in Cochlear Implantation Outcomes in a Large German Cohort With a Genetic Etiology of Hearing Loss. Ear Hear. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, J.; Terkildsen, K. Audiological findings in 125 cases of acoustic neuromas. Acta Otolaryngol. 1975, 80, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertner, A.B. Site of lesion testing findings in a routine test battery. Am J Otol. 1981, 2, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strasilla, C.; Synchra, V. Imaging-based diagnosis of vestibular schwannoma. HNO 2017, 65(5), 373-380. [CrossRef]

- Hoth, S.; Dziemba, O.C. The Role of Auditory Evoked Potentials in the Context of Cochlear Implant Provision. Otol Neurotol. 2017, 38, e522–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziemba, O. C.; Hocke, T.; Müller, A; EABR on cochlear implant – measurements from clinical routine compared to reference values. GMS Z Audiol (Audiol Acoust). 2022, 4. 4. [CrossRef]

- Wable, J.; Frachet, B.; Gallego, S. Tone decay at threshold with auditory electrical stimulation in digisonic cochlear implantees. Audiology. 2001, 40, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasmann, J.A.; van Eijl, R.H.M.; Versnel, H.; van Zanten, G.A. Assessing auditory nerve condition by tone decay in deaf subjects with a cochlear implant. Int J Audiol. 2018, 57, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).