Submitted:

13 December 2023

Posted:

14 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and objective

2. Previous studies

3. Materials and methods

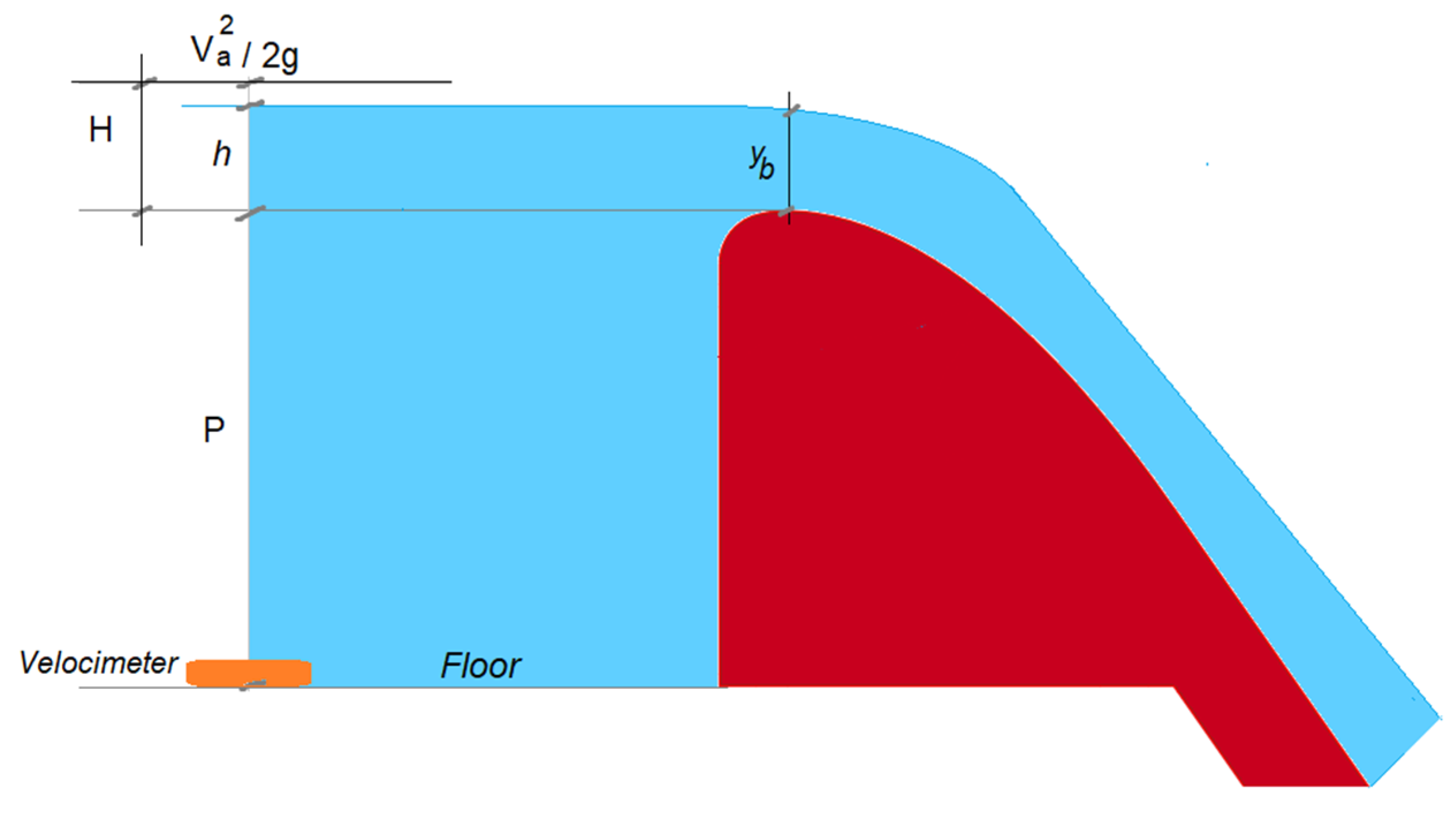

3.1. Experimental facility

3.2. Instrumentation

3.3. Operating conditions

4. Results

4.1. Spillway (P = 0.35 m and m)

4.2. Spillway (P = 0.30 m and m)

4.3. Spillway (P = 0.20 m and m)

4.4. Spillway (P = 0.10 m and m)

4.5. Spillway (P = 0.05 m and m)

4.6. Aggregated analysis P/Hd

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- −

- At altitudes above 4000 m a.s.l., the discharge coefficients show substantial differences compared to those obtained in other environments, resulting in consistently lower values than those obtained to date in previous works developed at lower altitudes above sea level.

- −

- The coefficient has a greater influence on the value of the discharge coefficient . The difference of at least 5% reflects fundamentally the influence of the greater curvature of the nappe over the spillway due to the reduction of atmospheric pressure in the zone.

- −

- The ratio influences the discharge coefficients in Condoroma, and values are recommended for the design of the spillway profile.

- −

- The equations to determine the discharge coefficients, equations (10), (11), and (12), for Condoroma could be used in areas with similar altitudes in the absence of experimental data.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S.B.R. Design of Small Dams, 1960, 1973, 1977 ed.; Bureau of Reclamation: 1987.

- Sotelo, G. Diseño hidráulico de obras; Facultad de Ingeniería - UNAM: Mexico, 1994.

- Poleni, G. De motu acque mixto; Raccolta di autori che affrontano il movimento dell'acqua, 2a edizione, Firenze, Italia. 1767: Patavii-Padua, 1717.

- Naudascher, E. Hidraulica de canales; Limusa: Mexico, 2002.

- Montes, S. Hydraulics of open channel flow; ASCE Press: 1998.

- Weisbach, J. Allgemeine maschinen enzyklopadie. 1841.

- Rouse, H. Fluid mechanics for hydraulic engineers, First ed.; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York - London, 1938.

- Russell, G. Hydraulics, 5th ed.; Henry Holt and Company, 1948.

- Horton, R.E. Weir experiments, coefficients, and formulas. 1907.

- Mueller, R. Development of Practical Type of Concrete Spillway Dam. Engineering Records 1908, 58, 461.

- Morrison, E.; Brodie, O. Mansory dam design., John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ed.; John Wiley & Sons, I., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 1916.

- Creager, W. Engineering for masonry dams, Jhon Wiley and Sons, New York, 1917,pp 105-110 New York, 1917.

- Nagler, F.; Davis, A. Experiments on discharge over spillway and models, Keokuk Dam. 1930; pp. 777-820, 844. [CrossRef]

- Dillmann, O. Untersuchungen an ueberfallen Mitteilungen des hydraulics institus der T.H. Munchen 1933, 7.

- Rouse, H.; Reid, L. Model research on spillway crest. Civil Engineering 1935, 5, 10.

- Doland, J. Flow over rounded crests. Engineering News Record 1935, 114, 551.

- Brudenell, R. Flow over rounded crests Engineering News Record 1935, 115, 95.

- Chow, V. Open-Channel Hydraulics; McGraw-Hill Book Company: 1959.

- Vitols, A. Vacuumless dam profiles. Wasserkraft und wasserwirtschaft 1936, 31, 207.

- Randolph, R.J. Hydraulic tests on the spillway of the Madden Dam. In Proceedings of the ASCE, 1937. [CrossRef]

- Borland, W. Flow over crest weirs. Civil Engineering - Colorado State, 1938.

- Bradley, J. Refinements in the design of overfall spillway sections; Bureau Reclamation United States: 1947.

- U.S.B.R. Studies of crests for overflow dams - Bulletin 3 Bureau of Reclamation: 1948; pp. 1 - 5.

- Webster, M. Spillway Design for Pacific Northwest Projects. Journal of the Hydraulics Division 1959, 85, 63-85. [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J. Spillway discharge at other than design head. State Univesity of Iowa, 1964.

- Cassidy, J. Designing spillway crests for high head operation. Journal of Hydraulics, ASCE 1970, HY3, 745 - 753. [CrossRef]

- Abecasis, F. Discussion of Designing spillway crests for high head operation. Journal of Hydraulics Division ASCE 1970, 96, 2654 - 2658. [CrossRef]

- Melsheimer, E.; Murphy, T. Investigations of various shapes of the upstream quadrant of the crest of a high spillway; Hidraulic Laboratory Investigation; Vicksburg, Miss, 1970.

- Senturk, F. Hydraulics of dams and reservoirs; Water Resouces Publications: 1994.

- Maynord, S. General Spilway Investigation; 1985.

- Hager, W. Experiments on standard spillway flow. In Proceedings of the Institute Civil Engineers, 1991; pp. 399 - 416.

- Erpicum, S.; Blancher, B.; Vermeulen, J.; Peltier, Y.; Archambeau, P. Experimental study of ogee crested weir operation above the design head and influence of the upstream quadrant geometry. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures, Aachen, Germany 2018.

- Aguilera, E.; Jimenez, O. Applicability of a 3D numerical model for flow simulation of spillways. In Proceedings of the 38th IAHR World Congress, Panama Cyti, Panama, September 1-6, 2019; p. 11.

- Salmasi, F.; Abraham, J. Discharge coefficients for ogee spillways. Water Suply 2022, 22, 17. [CrossRef]

- Stilmant, F.; Erpicum, S.; Peltier, Y.; Archambeau, P.; Dewals, B.; Pirotton, M. Flow at an Ogee Crest Axis for a Wide Range of Head Ratios: Theoretical Model. Water 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Fatemi, S.; Ghaderi, A.; Di Francesco, S. The Effect of Geometric Parameters of the Antivortex on a Triangular Labyrinth Side Weir. Water 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, A.; Daneshfaraz, R.; Dasineh, M.; Di Francesco, S. Energy Dissipation and Hydraulics of Flow over Trapezoidal–Triangular Labyrinth Weirs. Water 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zerihun, Y.T. Free Flow and Discharge Characteristics of Trapezoidal-Shaped Weirs. Fluids 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Deng, J.; Wei, W. Discharge Coefficient of a Round-Crested Weir. Water 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Diao, M.; Sun, H.; Ren, Y. Numerical Modeling of Flow Over a Rectangular Broad-Crested Weir with a Sloped Upstream Face. Water 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Di Bacco, M.; Scorzini, A.R. Are We Correctly Using Discharge Coefficients for Side Weirs? Insights from a Numerical Investigation. Water 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Granata, F.; Di Nunno, F.; Gargano, R.; de Marinis, G. Equivalent Discharge Coefficient of Side Weirs in Circular Channel—A Lazy Machine Learning Approach. Water 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Rouse, H. Discharge characteristics of the free overfall. Civil Engineering 1936, 6, 257 - 260.

- Schoder, E.T., B. Precise weir measurements. In Proceedings of the Trasactions, ASCE, 1929; p. 93.

- Eisner, F. Overfall tests to various model scales. Traslation WES 1933, 42.

- Ghetti, A. Effects of surface tension on the shape of liquid jets. Advanced Study Institute: Padova 1966, 424-475.

- Vischer, D., Hager, W. Dam Hydraulics Wiley Series: 1998.

- Hager W., S.A., Boes R. y Pfister M. Hydraulic Engineering of dams; 2021.

- Carrillo, J.; Ortega, P.; Castillo, L.; Garcia, J. Experimental Characterization of Air Entrainment in Rectangular Free Falling Jets. Water 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, F. Open Channel Flow; The Macmillan Company New York, 1966; p. 522.

- Rouse, H. The distribution of hydraulic energy in weir flow with relation to spillway design. Massachusetts Institute of Tecnology, 1932.

| Autor |

Length (m) |

Hd (m) |

P/Hd | Q (l/s) |

Elevation m a.s.l. |

| Dillman [14] | ------- | 0.05 | ----------- | ------ | 520 |

| Cassidy [26] | ------- | ------- | 2;2.5;3.7;6.6 | ------ | 210 |

| Rouse [43] | 0.500 | ------- | ---------- | 62 | 115 |

| Murphy [28] | 0.732 | 0.305 | 3.5;7.0 | 560 | 1600 |

| Maynord [30] | 0.762 | 0.249 | 0.25;0.5;1.0;2.0 | 385 | 1600 |

| Hager [31] | 0.500 | 0.20/0.1 | 3.5/7.0 | 375 | 495 |

| Erpicum [32] | 0.200 | 0.10/0.15 | ---------- | 358 | 65 |

| Condoroma dam | 0.915 | 0.20/0.175 | 0.25;0.5;1;1.5/2 | 415 | 4075 |

| Author | mo | n | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | Condoroma | 0.462 | 0.184 | 0.719 |

| 2.0 | Maynord [30] | 0.494 | 0.157 | 0.984 |

| 2.0 | Cassidy [26] | 0.518 | 0.186 | 0.993 |

| 2.5 | Murphy [28] | 0.503 | 0.139 | 0.974 |

| 3.5 | Hager [31] | 0.493 | 0.122 | 0.988 |

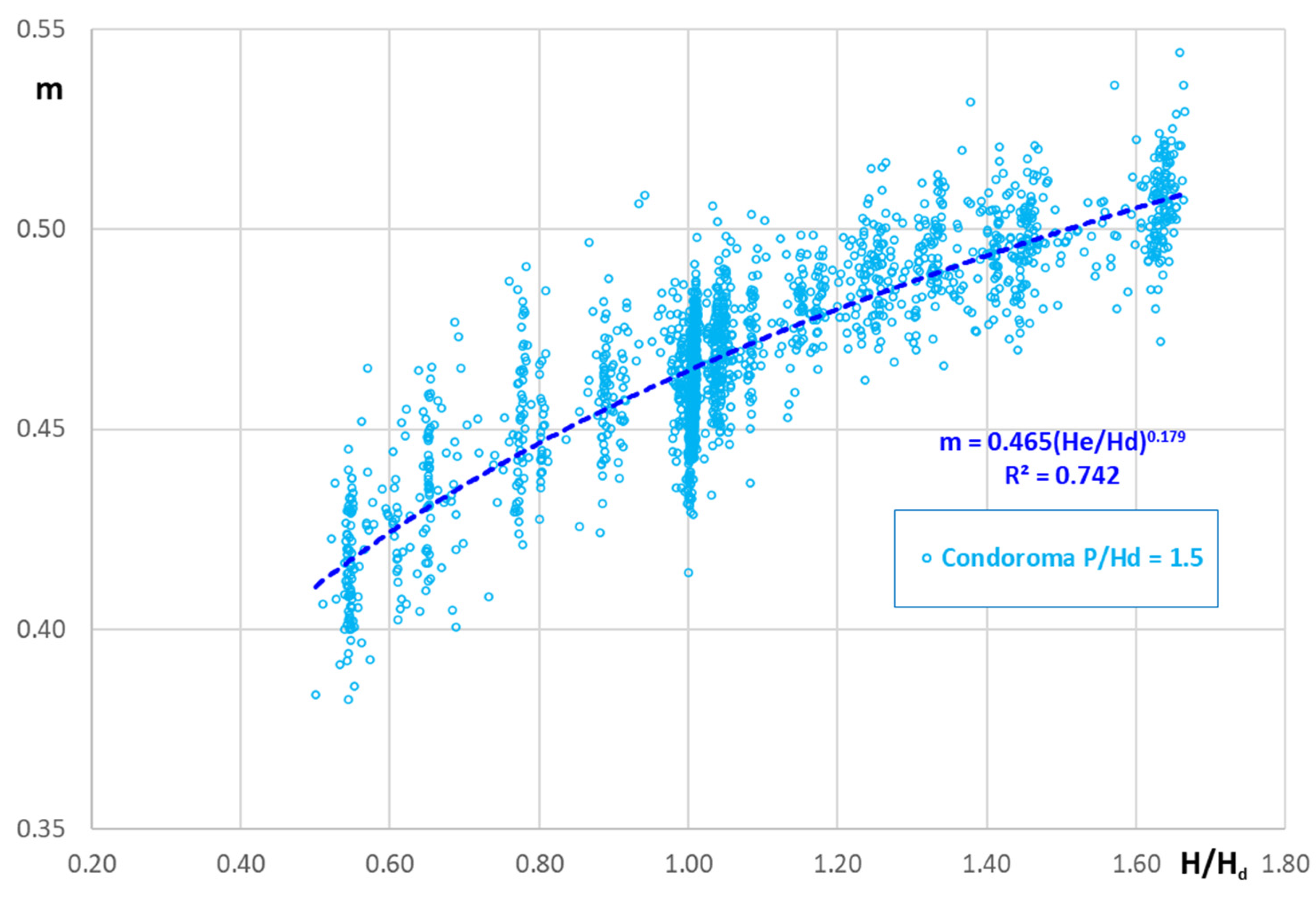

| 1.5 | Condoroma | 0.465 | 0.179 | 0.742 |

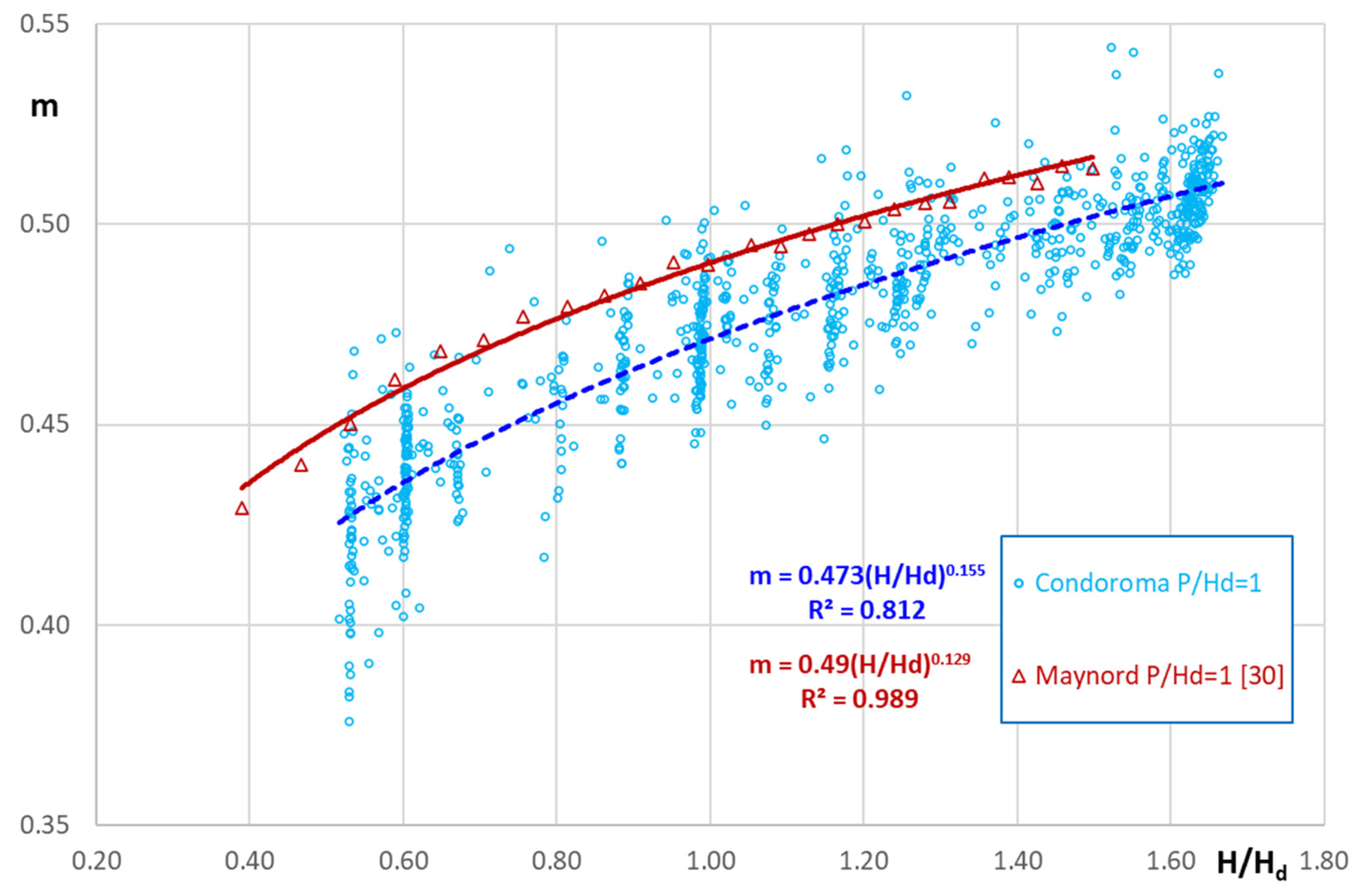

| 1 | Condoroma | 0.472 | 0.155 | 0.812 |

| 1 | Maynord [30] | 0.490 | 0.129 | 0.989 |

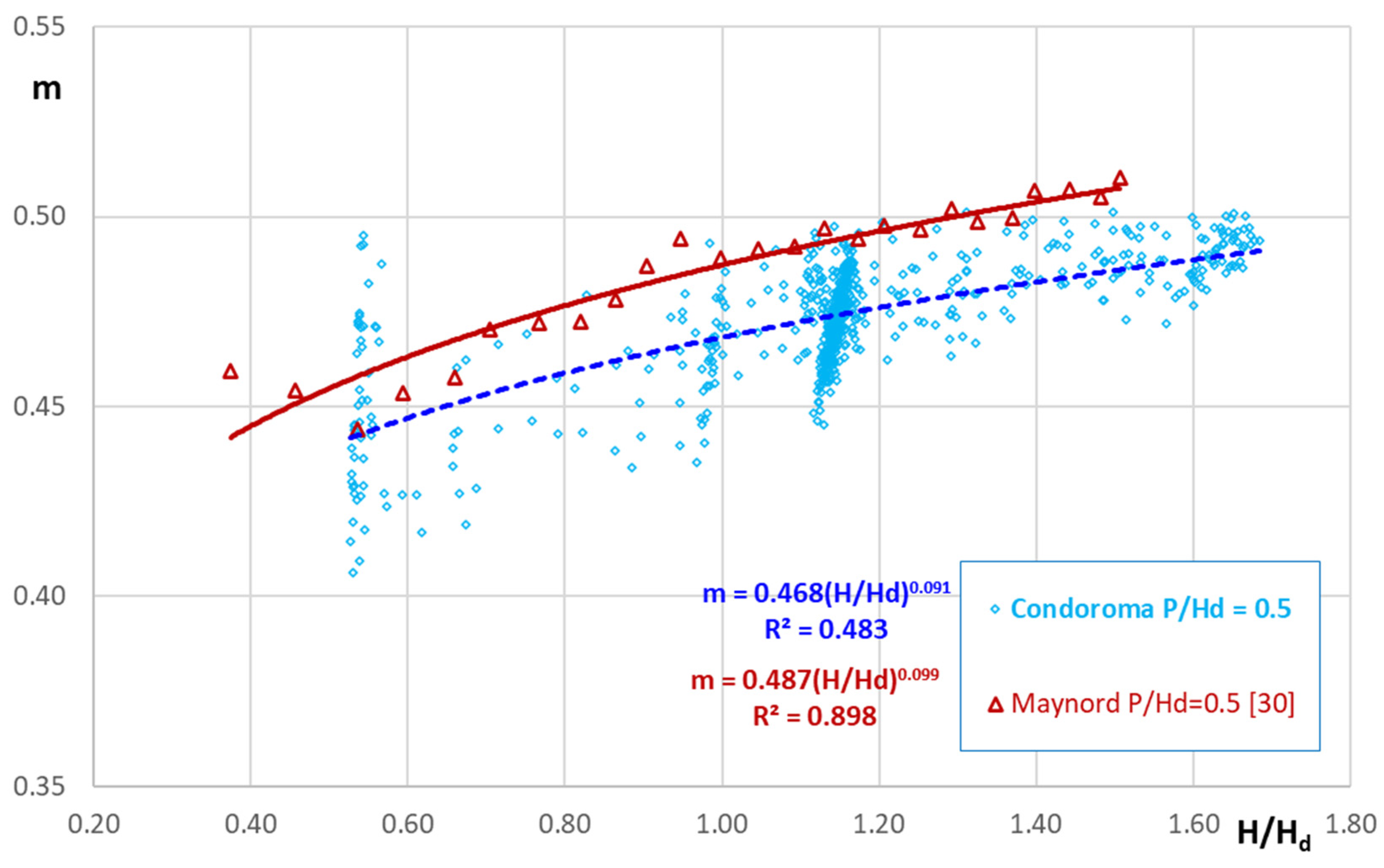

| 0.5 | Condoroma | 0.468 | 0.091 | 0.483 |

| 0.5 | Maynord [30] | 0.487 | 0.099 | 0.849 |

| 0.25 | Condoroma | 0.461 | 0.093 | 0.623 |

| 0.25 | Maynord [30] | 0.468 | 0.063 | 0.489 |

| Autor | mo | n |

|---|---|---|

| Dillman [14] | 0.512 | 0.147 |

| Rouse [15] | 0.510 | 0.147 |

| Brudenell [17] | 0.495 | 0.120 |

| Randolph [20] | 0.490 | 0.170 |

| Cassidy [26] | 0.518 | 0.186 |

| Montes [5] | 0.496 | 0.113 |

| Murphy [28] | 0.502 | 0.139 |

| Senturk [29] | 0.496 | 0.160 |

| Maynord [30] | 0.491 | 0.128 |

| Hager [31] | 0.495 | 0.129 |

| Erpicum [32] | 0.501 | 0.120 |

| Condoroma | 0.465 | 0.155 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).