Submitted:

14 December 2023

Posted:

14 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

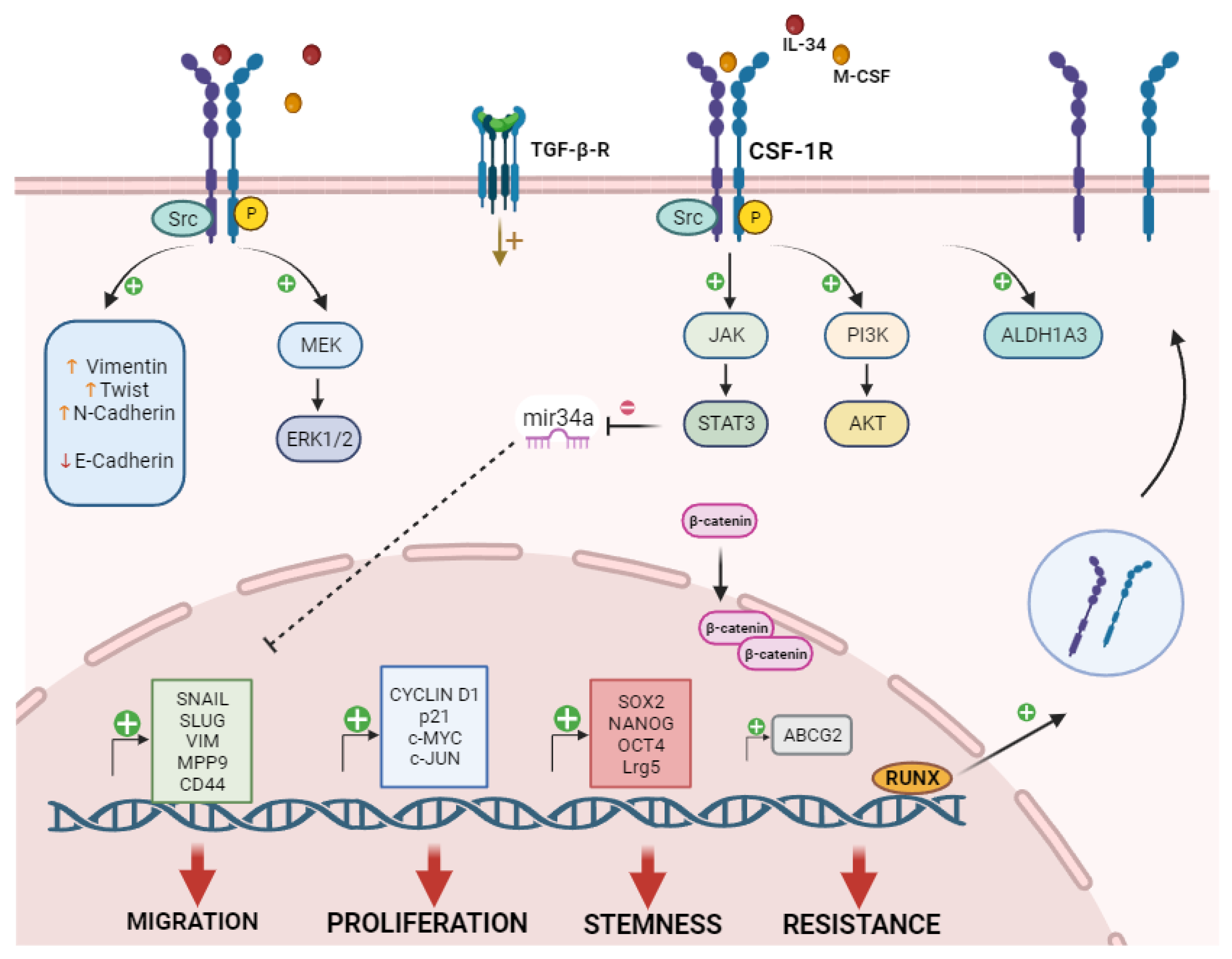

2. CSF-1R in Cancer

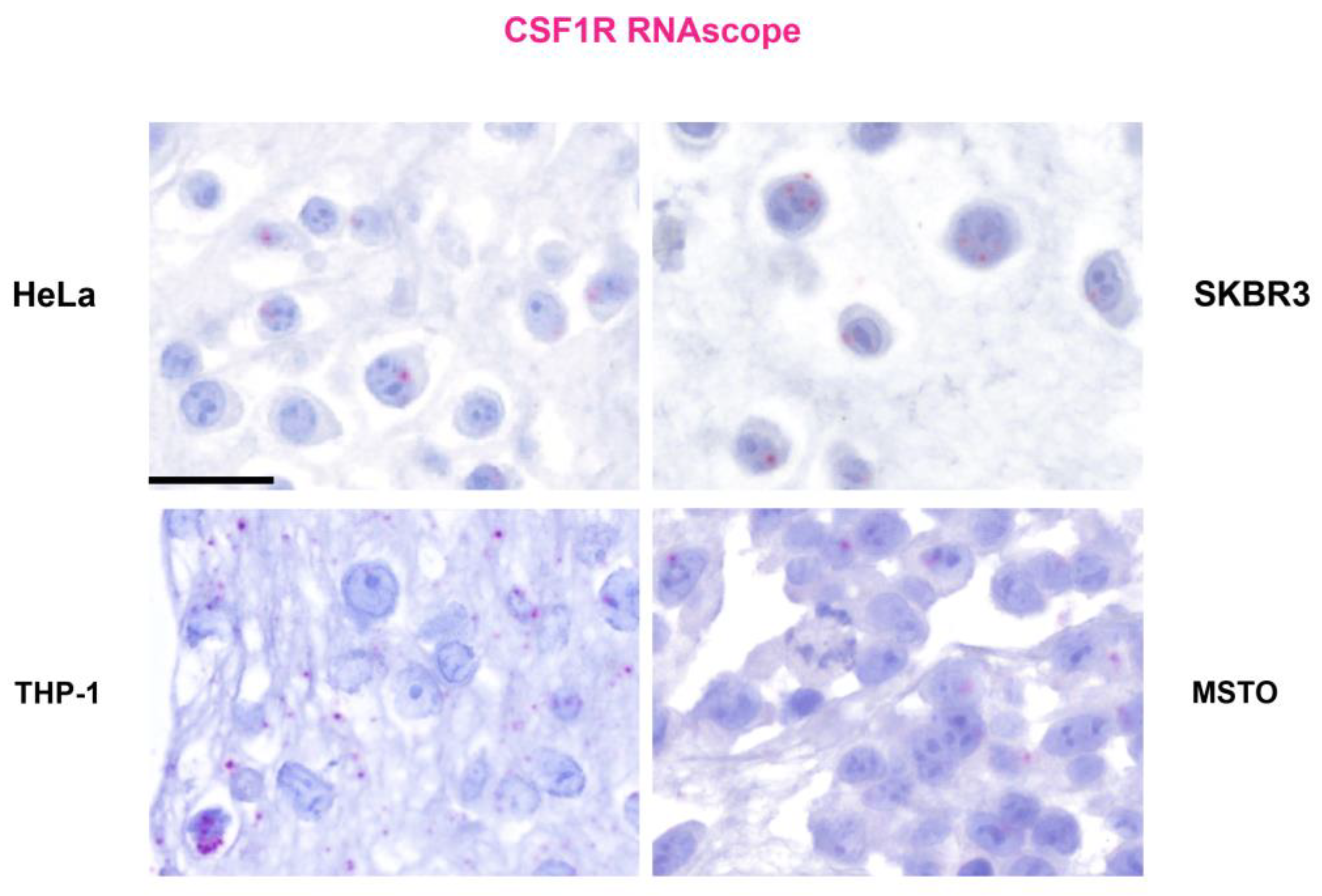

2.1. CSF-1R in Cancer Cells

2.2. Role of CSF-1R Ligands in TME Crosstalk

2.3. CSF-1R in Cancer Cell Proliferation

2.4. CSF-1R in Cancer Cell Migration

2.5. CSF-1R in Drug Resistance and Stemness

3. Anti-CSF-1R Therapeutic Strategies and Future Prospectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stanley, E.R.; Chitu, V. CSF-1 receptor signaling in myeloid cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a021857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo, R.; Pridans, C.; Langlais, D.; Hume, D.A. Transcriptional mechanisms that control expression of the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor locus. Clin. Sci. (Lond.), 2017, 131, 2161–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, Y.; Stawicki, S.; Mukhyala, K.; Wu, Y.; Martin, F.; Bazan, J.F.; Starovasnik, M.A. Structural basis for the dual recognition of helical cytokines IL-34 and CSF-1 by CSF-1R. Structure. 2012, 20, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Garcia, J.; Cochonneau, D.; Télétchéa, S.; Moranton, E.; Lanoe, D.; Brion, R.; Lézot, F.; Heymann, M.F.; Heymann, D. The twin cytokines interleukin-34 and CSF-1: masterful conductors of macrophage homeostasis. Theranostics. 2021, 11, 1568–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achkova, D.; Maher, J. Role of the colony-stimulating factor (CSF)/CSF-1 receptor axis in cancer. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannarile, M.A.; Weisser, M.; Jacob, W.; Jegg, A.M.; Ries, C.H.; Rüttinger, D. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitors in cancer therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2017, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buechler, M.B.; Fu, W.; Turley, S.J. Fibroblast-macrophage reciprocal interactions in health, fibrosis, and cancer. Immunity. 2021, 54, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sletta, K.Y.; Castells, O.; Gjertsen, B.T. Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 654817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, M.F. Regulation of cell cycle entry and G1 progression by CSF-1. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1997, 46, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, S.A.; Worwood, M.; Oscier, D.; Jacobs, A.; Padua, R.A. FMS mutations in myelodysplastic, leukemic, and normal subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990, 87, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, A.; Barbetti, V.; Riverso, M.; Dello Sbarba, P.; Rovida, E. The colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) receptor sustains ERK1/2 activation and proliferation in breast cancer cell lines. PloS one. 2011, 6, e27450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioce, M.; Canino, C.; Goparaju, C.; Yang, H.; Carbone, M.; Pass, H.I. Autocrine CSF-1R signaling drives mesothelioma chemoresistance via AKT activation. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giricz, O.; Mo, Y.; Dahlman, K.B.; Cotto-Rios, X.M.; Vardabasso, C.; Nguyen, H.; Matusow, B.; Bartenstein, M.; Polishchuk, V.; Johnson, D.B.; Bhagat, T.D.; Shellooe, R.; Burton, E.; Tsai, J.; Zhang, C.; Habets, G.; Greally, J.M.; Yu, Y.; Kenny; P. A., Fields; G., B.; … Verma, A.K. The RUNX1/IL-34/CSF-1R axis is an autocrinally regulated modulator of resistance to BRAF-V600E inhibition in melanoma. JCI Insight. 2018, 3, e120422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, M.G.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Rho, S.B.; Kim, B.R.; Jang, I.S.; Lee, S.H. TSC-22 inhibits CSF-1R function and induces apoptosis in cervical cancer. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 97990–98003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, C.H.; Cannarile, M.A.; Hoves, S.; Benz, J.; Wartha, K.; Runza, V.; Rey-Giraud, F.; Pradel, L.P.; Feuerhake, F.; Klaman, I.; Jones, T.; Jucknischke, U.; Scheiblich, S.; Kaluza, K.; Gorr, I.H.; Walz, A.; Abiraj, K.; Cassier, P.A.; Sica, A.; Gomez-Roca, C.; … Rüttinger, D. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer cell. 2014, 25, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, A.R.; Pixley, F.J. CSF-1R signaling in health and disease: a focus on the mammary gland. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 2014, 19, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacinski, B.M. CSF-1 and its receptor in breast carcinomas and neoplasms of the female reproductive tract. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997, 46, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, I.; Beck, A.H.; Lee, C.H.; Zhu, S.; Montgomery, K.D.; Marinelli, R.J.; Ganjoo, K.N.; Nielsen, T.O.; Gilks, C.B.; West, R.B.; van de Rijn, M. Coordinate expression of colony-stimulating factor-1 and colony-stimulating factor-1-related proteins is associated with poor prognosis in gynecological and nongynecological leiomyosarcoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 2347–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toy, E.P.; Azodi, M.; Folk, N.L.; Zito, C.M.; Zeiss, C.J.; Chambers, S.K. Enhanced ovarian cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis by the macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Neoplasia. 2009, 11, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ide, H.; Seligson, D.B.; Memarzadeh, S.; Xin, L.; Horvath, S.; Dubey, P.; Flick, M.B.; Kacinski, B.M.; Palotie, A.; Witte, O.N. Expression of colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor during prostate development and prostate cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 14404–14409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardsen, E.; Uglehus, R.D.; Due, J.; Busch, C.; Busund, L.T. The prognostic impact of M-CSF, CSF-1 receptor, CD68 and CD3 in prostatic carcinoma. Histopathology. 2008, 53, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuropkat, C.; Dünne, A.A.; Plehn, S.; Ossendorf, M.; Herz, U.; Renz, H.; Werner, J.A. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor as a tumor marker for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Tumour Biol. 2003, 24, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroczko, B.; Szmitkowski, M.; Okulczyk, B. Hematopoietic growth factors in colorectal cancer patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003, 41, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.F.; Kocher, H.M.; Salako, M.A.; Obermueller, E.; Sandle, J.; Balkwill, F. A novel function of colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor in hTERT immortalization of human epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2009, 28, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, H.; Hao, Y.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhou, S.; Yin, M. Overexpression of macrophage-colony stimulating factor-1 receptor as a prognostic factor for survival in cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021, 100, e25218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, N.; Burugu, S.; Cheng, A.S.; Leung, S.C.Y.; Gao, D.; Nielsen, T.O. (2021). Prognostic Significance of CSF-1R Expression in Early Invasive Breast Cancer. Cancers. 2021, 13, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Such, E.; Cervera, J.; Valencia, A.; Garcia-Casado, Z.; Senent, M.L.; Sanz, M.A.; Sanz, G.F. Absence of mutations in the tyrosine kinase and juxtamembrane domains of C-FMS gene in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). Leuk. Res. 2009, 33, e162–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirma, N.; Hammes, L.S.; Liu, Y.G.; Nair, H.B.; Valente, P.T.; Kumar, S.; Flowers, L.C.; Tekmal, R.R. Elevated expression of the oncogene c-fms and its ligand, the macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1, in cervical cancer and the role of transforming growth factor-beta1 in inducing c-fms expression. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 1918–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbetti, V.; Morandi, A.; Tusa, I.; Digiacomo, G.; Riverso, M.; Marzi, I.; Cipolleschi, M.G.; Bessi, S.; Giannini, A.; Di Leo, A.; Dello Sbarba, P.; Rovida, E. Chromatin-associated CSF-1R binds to the promoter of proliferation-related genes in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014, 33, 4359–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.J.; Pinto, M.; Henrique, R.; Vieira, J.; Cerveira, N.; Peixoto, A.; Martins, A.T.; Oliveira, J.; Jerónimo, C.; Teixeira, M.R. CSF1R copy number changes, point mutations, and RNA and protein overexpression in renal cell carcinomas. Mod. Pathol. 2009, 22, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaenepoel, O.; Tzenaki, N. , Vergetaki, A.; Makrigiannakis, A.; Vanhaesebroeck, B.; Papakonstanti, E.A. Functional CSF-1 receptors are located at the nuclear envelope and activated via the p110δ isoform of PI 3-kinase. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiatari, I.; Midelashvili, T.; Motsikulashvili, M.; Tchavtchavadze, A.; Tawfeeq, S.; Amiranashvili, I. OVEREXPRESSED PROGENITOR GENE CSF1R IN PANCREATIC CANCER TISSUES AND NERVE INVASIVE PANCREATIC CANCER CELLS. Georgian Med. News. 2018, (285), 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Filiberti, S.; Russo, M.; Lonardi, S.; Bugatti, M.; Vermi, W.; Tournier, C.; Giurisato, E. Self-Renewal of Macrophages: Tumor-Released Factors and Signaling Pathways. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, V.; Li, Z.; Blenis, J. Metabolite activation of tumorigenic signaling pathways in the tumor microenvironment. Sci Signal. 2022, 15, eabj4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cersosimo, F.; Barbarino, M.; Lonardi, S.; Vermi, W.; Giordano, A.; Bellan, C.; Giurisato, E. Mesothelioma Malignancy and the Microenvironment: Molecular Mechanisms. Cancers. 2021, 13, 5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzè, E.; Dinallo, V.; Rizzo, A.; Di Giovangiulio, M.; Bevivino, G.; Stolfi, C.; Caprioli, F.; Colantoni, A.; Ortenzi, A.; Grazia, A.D.; Sica, G.; Sileri, P.P.; Rossi, P.; Monteleone, G. Interleukin-34 sustains pro-tumorigenic signals in colon cancer tissue. Oncotarget. 2017, 9, 3432–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, H.; Hama, N.; Baghdadi, M.; Ishikawa, K.; Otsuka, R.; Wada, H.; Asano, H.; Endo, D.; Konno, Y.; Kato, T.; Watari, H.; Tozawa, A.; Suzuki, N.; Yokose, T.; Takano, A.; Kato, H.; Miyagi, Y.; Daigo, Y.; Seino, K.I. Interleukin-34 expression in ovarian cancer: a possible correlation with disease progression. Int. Immunol. 2020, 32, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.L.; Hu, Z.Q.; Zhou, Z.J.; Dai, Z.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Fan, J.; Huang, X.W.; Zhou, J. miR-28-5p-IL-34-macrophage feedback loop modulates hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Hepatology. 2016, 63, 1560–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondy, T.; d'Almeida, S.M.; Briolay, T.; Tabiasco, J.; Meiller, C.; Chéné, A.L.; Cellerin, L.; Deshayes, S.; Delneste, Y.; Fonteneau, J.F.; Boisgerault, N.; Bennouna, J.; Grégoire, M.; Jean, D.; Blanquart, C. Involvement of the M-CSF/IL-34/CSF-1R pathway in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2020, 8, e000182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzè, E.; Marafini, I.; Troncone, E.; Salvatori, S.; Monteleone, G. Interleukin-34 promotes tumorigenic signals for colon cancer cells. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Nakata, H.; Kubota, T.; Bandobashi, K.; Saito, T.; Taguchi, H. Effects of GM-CSF and M-CSF on tumor progression of lung cancer: roles of MEK1/ERK and AKT/PKB pathways. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2006, 18, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.; Endo, H.; Takano, A.; Ishikawa, K.; Kameda, Y.; Wada, H.; Miyagi, Y.; Yokose, T.; Ito, H.; Nakayama, H.; Daigo, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Seino, K.I. High co-expression of IL-34 and M-CSF correlates with tumor progression and poor survival in lung cancers. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.; Tian, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, X. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibition blocks macrophage infiltration and endometrial cancer cell proliferation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 3139–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.W.; Nambirajan, S.; Moffat, J.G. CSF-1 activates MAPK-dependent and p53-independent pathways to induce growth arrest of hormone-dependent human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1999, 18, 7477–7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsialou, A.; Wyckoff, J.; Wang, Y.; Goswami, S.; Stanley, E.R.; Condeelis, J.S. Invasion of human breast cancer cells in vivo requires both paracrine and autocrine loops involving the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 9498–9506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsialou, A.; Wang, Y.; Pignatelli, J.; Chen, X.; Entenberg, D.; Oktay, M.; Condeelis, J.S. Autocrine CSF1R signaling mediates switching between invasion and proliferation downstream of TGFβ in claudin-low breast tumor cells. Oncogene. 2015, 34, 2721–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, M.; Kim, G.; Bhattarai, P.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, H.S. Interleukin-34-CSF1R Signaling Axis Promotes Epithelial Cell Transformation and Breast Tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liang, H.; Yu, W.; Jin, X. Increased invasive phenotype of CSF-1R expression in glioma cells via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Cancer gene Ther. 2019, 26(5-6), 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murga-Zamalloa, C.; Rolland, D.C.M.; Polk, A.; Wolfe, A.; Dewar, H.; Chowdhury, P.; Onder, O.; Dewar, R.; Brown, N.A.; Bailey, N.G.; Inamdar, K.; Lim, M.S.; Elenitoba-Johnson, K.S.J.; Wilcox, R.A. Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF1R) Activates AKT/mTOR Signaling and Promotes T-Cell Lymphoma Viability. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanaburee, T.; Tipmanee, V.; Tedasen, A.; Thongpanchang, T.; Graidist, P. Inhibition of CSF1R and AKT by (±)-kusunokinin hinders breast cancer cell proliferation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Majchrzak, K.; Mucha, J.; Homa, A.; Bulkowska, M.; Jakubowska, A.; Karwicka, M.; Pawłowski, K.M.; Motyl, T. CSF-1R as an inhibitor of apoptosis and promoter of proliferation, migration and invasion of canine mammary cancer cells. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, C.N.; Debnath, J.; Lin, E.; Beausoleil, S.; Roussel, M.F.; Brugge, J.S. Autocrine CSF-1R activation promotes Src-dependent disruption of mammary epithelial architecture. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 165, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xu, X.; Hao, Y. The possible mechanisms of tumor progression via CSF-1/CSF-1R pathway activation. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2014, 55 (2 Suppl), 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- Sapi, E.; Flick, M.B.; Rodov, S.; Kacinski, B.M. Ets-2 transdominant mutant abolishes anchorage-independent growth and macrophage colony-stimulating factor-stimulated invasion by BT20 breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kai, K.; Iwamoto, T.; Zhang, D.; Shen, L.; Takahashi, Y.; Rao, A.; Thompson, A.; Sen, S.; Ueno, N.T. CSF-1/CSF-1R axis is associated with epithelial/mesenchymal hybrid phenotype in epithelial-like inflammatory breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toy, E.P.; Azodi, M.; Folk, N.L.; Zito, C.M.; Zeiss, C.J.; Chambers, S.K. Enhanced ovarian cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis by the macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Neoplasia. 2009, 11, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.Y.; Horn, D.; Woodruff, K.; Prihoda, T.; LeSaux, C.; Peters, J.; Tio, F.; Abboud-Werner, S.L. Colony-stimulating factor 1 potentiates lung cancer bone metastasis. Lab. Invest. 2014, 94, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.Q.; Li, X.G.; Zhang, Y.J.; Ling, Z.H.; Lin, X.J. Osteosarcoma cell-intrinsic colony stimulating factor-1 receptor functions to promote tumor cell metastasis through JAG1 signaling. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 801–815. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Kaller, M.; Rokavec, M.; Kirchner, T.; Horst, D.; Hermeking, H. Characterization of a p53/miR-34a/CSF1R/STAT3 Feedback Loop in Colorectal Cancer. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okugawa, Y.; Toiyama, Y.; Ichikawa, T.; Kawamura, M.; Yasuda, H.; Fujikawa, H.; Saigusa, S.; Ohi, M.; Araki, T.; Tanaka, K.; Inoue, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Miki, C.; Kusunoki, M. Colony-stimulating factor-1 and colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor co-expression is associated with disease progression in gastric cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2018, 53, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Bouznad, N.; Kaller, M.; Shi, X.; König, J.; Jaeckel, S.; Hermeking, H. Csf1r mediates enhancement of intestinal tumorigenesis caused by inactivation of Mir34a. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5415–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Jin, H.; Jin, C.; Huang, X.; Lin, J.; Teng, Y. Inhibition of the CSF-1 receptor sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin. Cell. Biochem. Funct. 2018, 36, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pass, H.I.; Lavilla, C.; Canino, C.; Goparaju, C.; Preiss, J.; Noreen, S.; Blandino, G.; Cioce, M. Inhibition of the colony-stimulating-factor-1 receptor affects the resistance of lung cancer cells to cisplatin. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 56408–56421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C. Clinical Development of Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF1R) Inhibitors. J. Immunother. Precis. Oncol. 2021, 4, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Wang, S.; Guo, R.; Liu, D. CSF1R inhibitors are emerging immunotherapeutic drugs for cancer treatment. Eur J Med Chem. 2023, 245 Pt 1, 114884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.S.; You, W.P.; Zhu, F.F.; Wang, J.H.; Guo, F.; Xu, J.J.; Liu, X.L.; Zhong, H.J. Targeted delivery of pexidartinib to tumor-associated macrophages via legumain-sensitive dual-coating nanoparticles for cancer immunotherapy. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces. 2023, 226, 113283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowski, R.; Sharma, N.; Reebel, L.; Rodal, M.B.; Peck, A.; West, B.L.; Marimuthu, A.; Severson, P.; Karlin, D.A.; Dowlati, A.; Le, M.H.; Coussens, L.M.; Rugo, H.S. Phase Ib study of the combination of pexidartinib (PLX3397), a CSF-1R inhibitor, and paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2019, 11, 1758835919854238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, O.; Wagner, A.J.; Kang, J.; Knebel, W.; Zahir, H.; van de Sande, M.; Tap, W.D.; Gelderblom, H.; Healey, J.H.; Shuster, D.; Stacchiotti, S. Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Pexidartinib in Healthy Subjects and Patients With Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumor or Other Solid Tumors. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 61, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. Pexidartinib: First Approval. Drugs. 2019, 79, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, S.; Koya, R.C.; Tsui, C.; Xu, J.; Robert, L.; Wu, L.; Graeber, T.; West, B.L.; Bollag, G.; Ribas, A. Inhibition of CSF-1 receptor improves the antitumor efficacy of adoptive cell transfer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thongchot, S.; Duangkaew, S.; Yotchai, W.; Maungsomboon, S.; Phimolsarnti, R.; Asavamongkolkul, A.; Thuwajit, P.; Thuwajit, C.; Chandhanayingyong, C. Novel CSF1R-positive tenosynovial giant cell tumor cell lines and their pexidartinib (PLX3397) and sotuletinib (BLZ945)-induced apoptosis. Hum. Cell. 2023, 36, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeester, B.A.; Slipek, N.J.; Pomeroy, E.J.; Laoharawee, K.; Osum, S.H.; Larsson, A.T.; Williams, K.B.; Stratton, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Peterson, J.J.; Rathe, S.K.; Mills, L.J.; Hudson, W.A.; Crosby, M.R.; Wang, M.; Rahrmann, E.P.; Moriarity, B.S.; Largaespada, D.A. PLX3397 treatment inhibits constitutive CSF1R-induced oncogenic ERK signaling, reduces tumor growth, and metastatic burden in osteosarcoma. Bone. 2020, 136, 115353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PROLIFERATION | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tumor type | Function | Reference |

| Breast Cancer | Cell cycle regulation p21 induction |

[44] |

| Breast Cancer | ERK1/2; c-Jun; Cyclin D; c-Myc activation | [11] |

| Breast Cancer | MEK/ERK; JNK/c-Jun c-Fos; c-Jun; AP-1activation |

[47] |

| Cervical Cancer | TSC-22-mediated proliferation | [14] |

| Melanoma | Pro-survival; anti-apoptotic | [13] |

| Glioma | P27 expression Increased cell viability Ki67-+ cells ERK1/2 activation |

[48] |

| T-cell lymphoma | PI3-K/AKT activation | [49] |

| Breast Cancer | G2-M markers expression | [50] |

| Mammary epithelial tissue | Hyperproliferation | [52] |

| MIGRATION | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tumor type | Function | Reference |

| Mammary epithelial tissue | Destruction of acinar architecture E-Cadherin re-localization Src-kinase activity |

[52] |

| Breast Cancer | Invasiveness and metastases | [46] |

| Breast Cancer | EMT | [55] |

| Ovarian Cancer | Adhesion and motility Tumor metastases Increased Urokinase surface expression |

[19] |

| Lung Cancer | Osteolytic metastases | [57] |

| Osteosarcoma | EMT via JAG-1 pathway activation | [58] |

| Colorectal Cancer | EMT markers expression STAT3 induction Mir-34a downregulation |

[59] |

| Glioma | EMT | [48] |

| Melanoma | Invasiveness | [13] |

| Gastric Cancer | Cell migration and Tumor metastasis | [60] |

| DRUG RESISTANCE & STEMNESS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tumor type | Function | Reference |

| Melanoma | BRAF resistance | [13] |

| Colorectal cancer | ALDH activity mir-34a downregulation |

[59] |

| Mesothelioma | ALDH activity Stem-like markers expression AKT pathway activation |

[12] |

| Intestinal adenoma | Stem-like gene expression | [61] |

| Ovarian Cancer | Cisplatin resistance AKT; ERK1/2 pathway activation |

[62] |

| Lung Cancer | Cisplatin resistance Stem-like markers expression |

[63] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).