1. Introduction

In the realm of healthcare, the concept of informed consent, first coined in 1957, stands as a pivotal ethical cornerstone, ensuring the safeguarding of patients’ and research participants’ welfare [

1]. This indispensable concept encapsulates a communicative process wherein patients are provided comprehensive information regarding the potential benefits and risks associated with a proposed treatment. In reciprocation, the patient, armed with this knowledge, consents to the recommended course of action or intervention. The validity of informed consent hinges upon several fundamental criteria, each playing a crucial role in upholding ethical standards. These include the patient’s capacity to comprehend the relevant facts about the proposed treatment and available choices, the voluntary nature of the consent to prevent coercion, and the necessity for the consent to be informed and sufficiently specific [

2,

3]. While written consent might not be imperative for straightforward procedures, its significance becomes paramount in the realm of complex, extensive, or multifaceted interventions, such as those encountered in orthodontics. Orthodontists, like all health care professionals, have an ethical obligation to communicate the potential risks and benefits before starting treatment, so that patients are aware and prepared for any adverse conditions or problems that could arise from the treatment [

4]. While an orthodontist is guided to diagnosis and treatment planning from objective factors that are derived from clinical screening and adequate analyses; orthodontic patients are driven by subjective factors like their perception of the problem, their needs, and desires [

5]. Therefore, in properly addressing the patient’s concerns and expectations, a patient-centered approach must be implemented. Still, nowadays the risk assessment should be a fundamental professional management and marketing strategy of the orthodontic practice that is used during the assessment of any orthodontic anomaly and its proposed treatment and could also be a part of the post treatment care policy [

4,

6,

7].

An informed consent which attempts to bridge the gap between the clinician’s perspective and the patients’ expectations must include all adequate information regarding treatment goals and proposed alternatives. Additionally, important issues like a patient’s cooperation, treatment duration, possible discomfort and various adverse effects which might arise during or after treatment must be thoroughly presented [

8].

In the literature the main risks involved with orthodontic treatment are periodontal problems like gingivitis or bone loss; cavities and root resorption or even tooth necrosis [

9,

10,

11,

12]. If there is a lack of proper oral hygiene, caries or enamel decalcifications might appear [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In addition, altered speech especially at treatment’s onset or psychological distress due to the appliances’ visibility might trouble the patient [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Allergic reactions to the materials used have also been recorded [

22]. Aesthetic problems like black triangle appearance and failure of tooth displacement might complicate the orthodontic treatment [24]. The patient should also be informed of the possible need for extraction of teeth, surgical procedures, and the possibility of relapse [25–28]. Other risks during orthodontic treatment include appliance breakage; detached brackets; broken or protruding wires as well as the possibility of swallowing detached brackets or other orthodontic appliances [29,30]. Lately, the possibility of transmission of infectious diseases within the dental office like Covid -19 has also been given particular attention [31].

This study aimed to assess the extent of informed consent practices in orthodontics within Greece and Slovakia. Specifically, it sought to analyze the perspectives of orthodontists in these two European countries, unveiling the nuanced variations shaped by individual characteristics and cultural factors. Furthermore, the research project intends to propose a comprehensive risk communication protocol tailored to orthodontic patients. This protocol is envisioned as an integral component of the consent process, contributing to the delivery of high-quality orthodontic treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Βackground of the study

The current research endeavors to comprehensively assess the multifaceted landscape of risk factors associated with orthodontic interventions, aiming to enhance our understanding of potential challenges and complications that may arise during orthodontic treatment. Drawing upon scholarly works by Naranjo (2006) [32], Weltman (2010) [33], Renkema (2013) [34], and others, our investigation encompasses a spectrum of potential risks such as periodontal problems; cavities; discomfort or pain during orthodontic movements; root resorption of teeth; tooth necrosis; dental caries; calcifications; difficulty in speaking; extractions during treatment; allergic reactions to orthodontic materials; failure of desired tooth movement; appearance of black triangles and aesthetic problems; recurrence of the orthodontic effect; and practical issues such as machine breakage and detached brackets. This study adopts a methodological approach grounded in the systematic administration of a comprehensive questionnaire, strategically designed to elicit nuanced responses from orthodontic practitioners. Through this research, we aim to discern patterns, prevalence, and severity of these risks, ultimately contributing to the development of informed guidelines for risk assessment in orthodontic practice.

From the extensive literature review conducted, a series of pertinent questions have emerged to guide the methodology of our research on risk assessment in orthodontics. First, we investigated the degree of importance assigned by orthodontists to various treatment risks. Additionally, we aimed to explore the specific risks that orthodontists prioritize when communicating information to their patients, along with the timing and methods employed in conveying these risks. Demographic factors such as gender, age, ethnicity, education level, professional experience, and financial background were scrutinized to discern potential influences on risk communication practices. Furthermore, we searched to ascertain whether differences exist in risk communication when conducted by orthodontists in comparison to auxiliary staff. The anticipated outcomes of improving orthodontist-patient information have been probed, shedding light on the objectives sought by orthodontic practitioners, while also considering the estimated time dedicated to this purpose. To comprehensively address the subject, we have also investigated the deficiencies perceived by professional orthodontists regarding risk communication and thereby identified educational actions deemed necessary for enhancing the communication approach in orthodontic patient care. This methodological framework was designed to yield valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of risk assessment in orthodontic practice (

Table 1).

2.2. Methodology of designing the study questionnaire

In conducting this study, we employed a well-established research technique based on questionnaire data selection, as referenced in previous studies [48–53]. The technique, executed in two rounds as previously described [53], underwent preliminary testing through a pilot study conducted in September 2022. This initial phase involved a small sample of orthodontists from the Dental School of Athens, Greece. The primary objective was to assess the feasibility and clarity of the preliminary questionnaire. The questionnaire was initially designed in English and reviewed by an English-speaking dental professional. Subsequently, it underwent translation and scrutiny by team members proficient in the Greek language. Ten orthodontists, including faculty members and postgraduate students, voluntarily participated in interview-based sessions to assess comprehensibility. The questions for the study were derived from a comprehensive review of the literature on the topic as previously described. At the outset of the process, we identified 15 primary questions, drawn from the literature review, which served as the foundation for the final questionnaire employed in the study.

The final questionnaire had a first part describing instructions of participation (

Appendix A) and four distinct sections with questions (

Appendix B). Part 1 consisted of 10 questions regarding the participants’ which included gender, age, country, marital status, children, degree in dentistry, other degrees, years in specialty, employment status, and team members. Part 2 gauged the perceived importance of the 15 identified risks from the initial survey round, featuring questions Q1-Q27. Respondents utilized a 5-point Likert scale (1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, 5=always) to express their evaluations. Part 3 focused on practical professional aspects of the orthodontic procedure, incorporating six additional questions (Q28-Q33). These questions delved into professional and practical dimensions such as marketing and clinic management; time estimation; timing of the communication approach; and economic impact assessment. Lastly, Part 4 was comprised of two open-ended questions allowing participants to articulate challenges encountered in risk communication and offer suggestions for educational enhancements.

The questionnaire underwent translation and validation in both the Greek and Slovak languages by team members and five professional (non-university) orthodontists in each country. Criteria for participant inclusion were orthodontists and postgraduate orthodontic students, while dental students, general dentists, and orthodontists practicing abroad without specialization were excluded. An e-questionnaire, which was uploaded via Google Forms, and a country-specific QR code were provided for ease of completion. Participants were assured of anonymity, with no collection of personal data in either country. Participation was voluntary, and no incentives were offered. Each orthodontist responded only once, and the questionnaire remained open for three months. Biweekly participation reminders, along with instructions and the questionnaire link, were disseminated by the secretariat of each association. Authorization to send the link to participants in Slovakia was given by the Slovak Orthodontic Society (committee decision on 22/9/2022) which has a total number of 210 members (NS1). In Greece there are four main orthodontic societies. The Greek team got approval from the Greek Association for Orthodontic Study & Research (committee decision on 13/9/2022) for sending the questionnaire to their 493 members (NS2) (Total number of orthodontists in Greece: 575). In both countries all procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines and have been approved by the appropriate authorities. Informed consent was obtained by participants while submitting the questionnaire.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for all the parts of the survey. Regarding inferential analysis, the outcome variables were the scores of Part 2 (Q1-Q27) survey questions (range 1: never to 5: always). The data were approximately distributed normally and after log-transformation, the data follow normal distribution, according to Shapiro-Wilk test for normality (p>0.05). Therefore, potential bivariate associations between orthodontists’ socio-demographic characteristics and the scores for Part 2 survey questions were assessed using t- test and ANOVA. In addition, multiple linear regression models were applied having as predictors the demographic characteristics, and as outcomes the scores for Part 2 survey questions. All reported probability values (p values) were compared with a significance level of 5% (p < 0.05). The analysis of coded data was carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

3. Results

N1 (91) questionnaires were filled in Slovakia (response rate = 43.3%) and N2 (77) questionnaires were filled in Greece (response rate =15,61%). The internal consistency of Part 2 of the survey (Q1-27) was very satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.87).

Demographic characteristics showed that the sample consisted of 115 females (68.5%) and 53 males (31.55%). Most participants (25.0%) were between the ages of 41 and 50, with the lowest percentage (11.19%) being under the age of 31. Furthermore, most respondents (67.9%) were married with one or two children (54.2%). In terms of academic qualifications, 68.4% have a master’s degree, while 17.3% have a PhD. Most of the participants have 1-10 years of experience in the field of orthodontics, while 28% of them have been practicing orthodontics for 11-20 years.

Statistically significant differences were found on frequencies of higher education between the two countries. Greek orthodontists reported Master and PhD degrees in significantly higher frequency compared to their Slovak counterparts (72/77=93.5% vs 72/91=79.1%, respectively, χ

2=16.832, p<0.001) as seen in

Table 2.

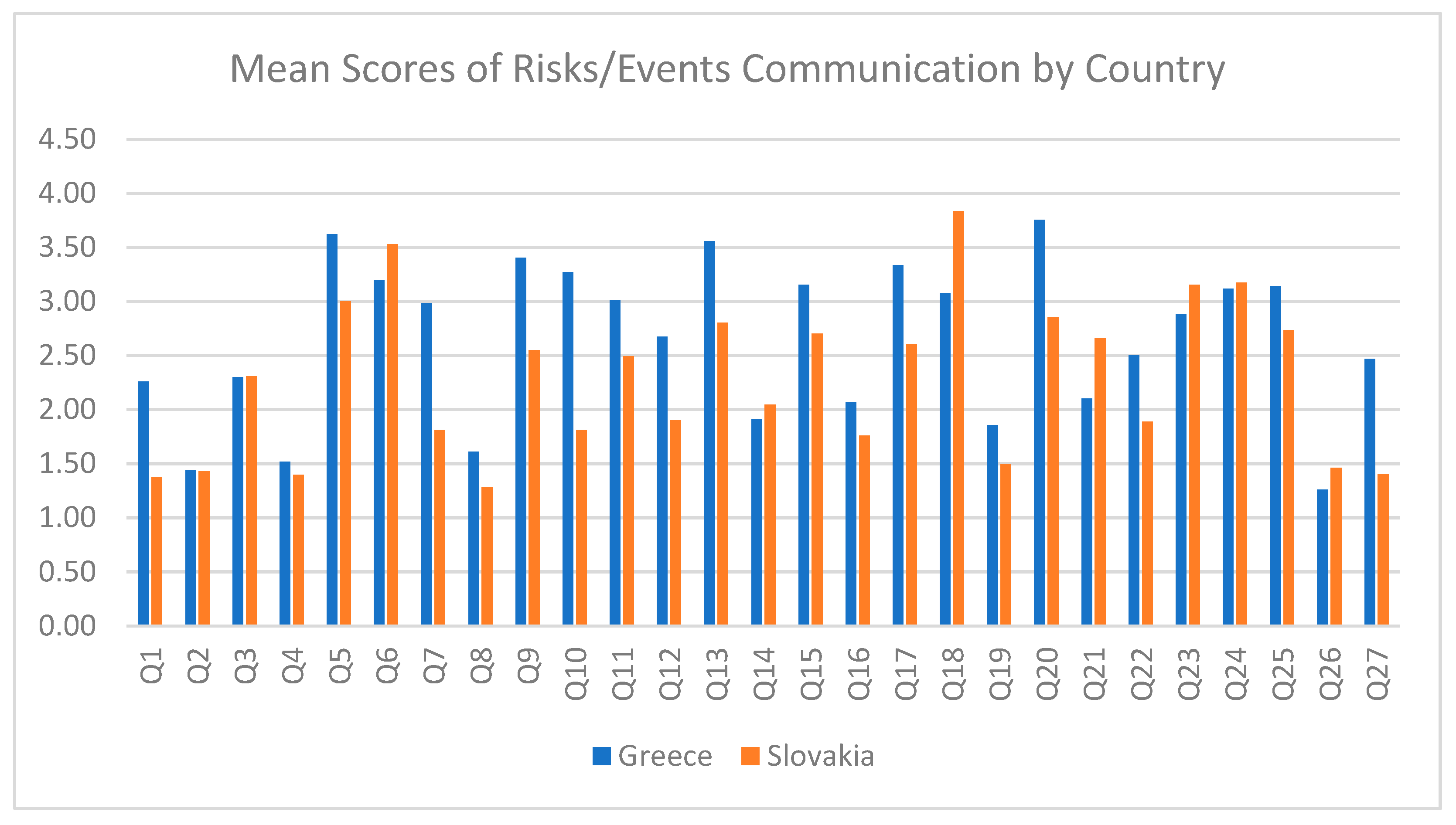

In part 2, we indicated that some risk assessment questions received a higher score of importance from participants. As seen in

Figure 1, these questions were: Q5. “Do you mention the possibility of tooth root resorption?”, Q6. “Do you mention the possibility of tooth necrosis?”, Q13. “Do you mention the possibility of temporary undesired changes to the occlusion?”, Q18. “Do you mention the possibility of sleep difficulties?”, and Q20. “Do you mention the possibility of not achieving an ideal result?”

Results from bivariate associations between risk/events communication survey questions score and orthodontists sociodemographic parameters are seen in

Table 3. A country-wise comparison revealed statistically significant differences in responses to questions Q1, Q5, Q7-10, Q13, Q15-18, Q20-22, and Q27. Specifically, Greek orthodontists expressed higher concern about potential risks such as relapse of orthodontic treatment; root resorption; temporal occlusal changes; and failure of desired movement of specific teeth. They also showed greater apprehension about the following: extractions during treatment; additional x-rays; idiopathic inability of tooth eruption; inclusion or ankylosis of teeth; failure to achieve the desired outcome; protective splint during sport activities; difficulties in mastication, speech, and sleep. Additionally, significant differences emerged in the communication of the duration of orthodontic treatment and the possibility of emergency visits due to practical problems. Slovak practitioners tend to be interested more about the following in diminishing order: sleeping difficulties; temporary undesired changes in occlusion; and not achieving an ideal result; using a protective splint during sports’ activity; duration of treatment and number of individual visits. They also tend to obtain written or digital consent from patients or their parents/guardians more frequently than the Greek team.

In terms of gender comparison, significant differences were found in responses to questions Q1, Q6, Q7, Q10, Q12, Q19, and Q27. Male participants appeared more inclined to discuss the risks of relapse; the failure of desired movement of some teeth; the need for extractions during treatment; possibly finding an idiopathic inability to erupt; inclusion or ankylosis of teeth; tooth necrosis; and the need for modified oral hygiene instructions when compared to their female counterparts. Conversely, female obtained written or digital consent from their patients or their patients’ parents/guardians more frequently.

Regarding degree comparison, statistically significant differences were observed only in questions 1 and 12. PhD responders were more likely to emphasize the risk of failure of the desired movement of some teeth and the possibility of finding idiopathic inability to erupt, inclusion, or ankylosis of teeth.

Experience in the profession demonstrated a statistically significant difference in response to question Q6. Orthodontists with 1-10 years and those with 31 or more years of experience communicated the risk of tooth necrosis more frequently than their counterparts, and notably, at the same frequency.

The results of multiple linear regression analysis in

Table 4 indicated that Slovak orthodontists reported significantly lower scores for survey questions Q1, Q7, and Q27 of part 2 compared to their Greek counterparts, after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. This suggests that sociodemographic factors may contribute to variations in the perception and communication of risks/events among orthodontists from different countries.

In the question Q 28- 33 we collected data about marketing habits and procedures of the participants seen in

Table 5. According to marketing habits, 89.3% of participants outline the risks again during orthodontic treatment. Additionally, 86.3% of doctors discuss the risks to their patients themselves. The average time spent on patient information is 15 to 30 minutes, with the majority using digital images or videos. Moreover, it appears that the clinic’s website is the most frequently used marketing communication tool (

Table 5).

In part 4, we collected participants’ views on frequent challenges during risk communication and helping tools to resolve the issues. We found that the lack of patients’ interest/cooperation, lack of time, patients’ misinformation, and the difficulty of patients to remember instructions are the most common problems faced by professionals when communicating risks (

Table 6).

To further address our data collection, we could mention some of the participants original views on the matter proposed more time and written information according to the standards of the informed consent of the American Association of Orthodontists (AAO) which ideally will be sent to the interested parties by email prior to their clinical appointment so that they have time to read it and discuss any questions that may arise. This presupposes confirmation of the appointment and a corresponding visit/consultation fee, despite whether treatment begins or not, since the time spent by the doctor on the information is not negligible.

4. Discussion

The communication of therapeutic risks is a cornerstone in health sciences, forming the basis for valid consent; shared decision-making; and the delivery of person-centered care [54]. This study delves into the perspectives of orthodontists in two European countries, shedding light on the nuances of risk communication in orthodontic practice. Orthodontists in both countries seem to acknowledge the importance of risk communication and assess risk accordingly. The literature underscores the importance of effective risk communication in orthodontics, emphasizing the necessity of conveying potential risks to patients [54,55]. However, despite this acknowledgment, orthodontists participated in our study may not consistently communicate certain treatment risks, as indicated by Bernabe et al.’s findings, which highlight the omission of risks related to eating and speaking [55]. This echoes the common clinical dilemma of deciding which risks should be communicated, a decision that is influenced by various factors such as the orthodontist’s social characteristics, their gender and experience; and by demographics [56].

In our study, a comprehensive country-wise comparison exposed notable distinctions in the types of risks prioritized and the modalities of consent employed by orthodontists. Greek practitioners exhibited a distinct focus on communicating potential risks, emphasizing aspects such as relapse; root resorption; temporal occlusal changes; and failure of desired movement. This emphasis aligns with the findings of studies such as Cohen and Yen (2014) [57] and Hancox et al. (2014) [58], which have discussed the significance of informed consent in orthodontic treatment and the variations in emphasis on these specific risks. Conversely, Slovak orthodontists displayed a focus on sleeping disorders; tooth resorption; temporary occlusion changes; not achieving an ideal result and a preference for written or digital consent practices, reflecting a divergence in communication strategies that corresponds with insights from studies such as Kumar et al. (2016) [59] and Baskin et al. (2000) [60]. The contextual variations highlighted by these disparities underscore the influence of regional factors and professional practices on the nuanced landscape of risk communication in orthodontics, as further expounded in studies like Clementini et al. (2018) [61].

A closer examination of gender and degree comparisons in our investigation revealed noteworthy variations in risk communication strategies among orthodontists. Male practitioners demonstrated a higher frequency in discussing specific risks, highlighting factors such as relapse, failure of desired movement, and the potential for extractions during treatment. On the other hand, female orthodontists exhibited a predilection for obtaining written or digital consent, reflecting a distinct approach to the communication of treatment risks. These findings align with insights from other studies [56,58,59], which delve into gender-related differences in orthodontic risk communication practices.

Furthermore, in our investigation, an in-depth analysis of degree comparisons in orthodontic risk communication revealed distinctive patterns. Orthodontists with a PhD degree demonstrated a heightened awareness of specific risks, particularly emphasizing the importance of discussing the failure of desired movement of certain teeth and the potential discovery of idiopathic inability to erupt. These findings align with the insights provided by studies like Perry et al. (2021) [56], which explore the impact of professional qualifications on risk assessment and communication. The observed variations in risk communication strategies based on academic degrees underscore the necessity for tailored approaches that consider individual characteristics and diverse professional backgrounds. This notion is further supported in other studies [60,61] emphasizing the importance of understanding how educational background influences risk communication practices in orthodontics.

Perry et al. (2021) [56] in his study conducted a comprehensive analysis, identifying 30 evidence-based risks in orthodontic treatment, culminating in the identification of 10 critical risks that should be consistently communicated to patients. These risks include demineralization/caries; relapse; length of treatment; root resorption; pain/discomfort; the consequences of doing nothing; appliances breaking; failure to achieve desired tooth movements; gingivitis; and mucosal ulcerations. In alignment with this evidence, our study delved into risk evaluation among orthodontists, encompassing a spectrum of 15 risks including root necrosis; temporary undesired changes to the occlusion; the possibility of sleep difficulties; not achieving an ideal result; the development of black triangles between teeth; the possible need of taking additional X-rays; possible speech difficulties; having to use a protective splint during sports activity; the duration of orthodontic treatment and the number of individual visits involved; the possibility of transmission of infectious diseases within the dental office; and swallowing detached brackets or other orthodontic appliances. The outcomes highlighted specific concerns, with the following: root resorption; root necrosis; temporary undesired changes to the occlusion; not achieving an ideal result; the duration of orthodontic treatment; and the potential for sleep disorders emerging as the most critical topics for discussion. These findings contribute valuable insights to the ongoing discourse on orthodontic risk communication, complementing the evidence-based approach advocated by Perry et al. (2021) [56] and offering another perspective on the risks prioritized by orthodontic practitioners in diverse clinical settings. These specific risks should be addressed during the informed consent process, ideally, being emphasized through verbal communication by the orthodontist. Discrepancies between our study’s results and existing data suggest potential influences from socio-demographic parameters and the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly with issues related to the transmission of infectious diseases in the dental clinic [62–64]. These differences underline the dynamic nature of risk communication in orthodontics, whereas external factors and evolving contexts contribute to variations in practitioners’ perspectives and practices such as the ones addressed in our study.

The practical implementation of informed consent remains a subject of investigation. Carr’s study [65] suggested a verbal review of consent, focusing on the initial points presented in a slide presentation, while Carter and Al-Diwani (2022) [66] found no significant differences among different methods of informed consent. Skulski et al.’s study [67] on the other hand, emphasized the positive impact of rehearsal interventions on recall and comprehension, that highlighted the potential benefits of incorporating educational strategies into the consent process [65–67]. In our study, orthodontists exhibited a modernized approach to patient communication by frequently employing digital images and videos for the presentation of treatment risks, as discussed by Lee et al. (2006) [68] and Terry and Cain (2016) [69]. This contemporary method underscores the field’s recognition of the importance of visual aids in enhancing patient understanding. The prevalent adoption of obtaining written or digital consent, in line with current technological trends in healthcare, reflects the broader integration of technology into orthodontic practices [70,71]. This aligns with the shifting landscape of healthcare towards digitalization and emphasizes the orthodontic community’s commitment to staying abreast of technological advancements. Additionally, the reported repetition of risk discussions during orthodontic treatment, a practice observed in 89.3% of participants, as discussed by Kellar (2009) [72], emerged as an effective strategy for improving patient comprehension. This repetition aligns with the principles of informed consent, thus enhancing patient awareness and understanding of potential risks throughout the course of their orthodontic journey.

Moreover, the incorporation of risk assessment into orthodontic practice is a multifaceted endeavor as derived from our data, transcending clinical realms to involve strategic professional management and marketing considerations as also discussed elsewhere [4,73,74]. This holistic approach aligns with the ethical imperative of transparent communication, where potential risks are explicitly conveyed to patients before treatment initiation [75,76]. Such communication is not merely a moral obligation but a pivotal aspect contributing to patient awareness and preparedness for any conceivable adverse conditions that might arise [77]. Our findings emphasize the significance of shared decision-making and patient autonomy in the clinical encounter, acknowledging that informed patients are better equipped to actively participate in their orthodontic journey. This aligns with the evolving landscape of healthcare, where transparency not only serves ethical principles but is also instrumental in fostering a patient-centered approach and optimizing overall treatment outcomes [78,79].

Given all findings from our study on risk communication practices in orthodontic settings in Greece and Slovakia, a relevant protocol for informed consent, recommended out of the data derived from this study, is presented in

Table 7.

The proposed research, focusing on the incorporation of a communication protocol into orthodontic practices in Greece and Slovakia, carries substantial benefits not only for the two mentioned countries but also for the broader international community of orthodontics. By enhancing the informed consent process, practitioners are poised to elevate patient care, promoting a model that aligns with contemporary healthcare trends emphasizing transparency and patient-centered care. The tailored communication protocol considers individual and cultural variations, addressing the specific needs and preferences of patients in diverse contexts. This approach not only respects the unique characteristics of patients but also contributes to the globalization of best practices in orthodontics. The research findings provide valuable lessons derived from the variations in risk communication practices among orthodontists in Greece and Slovakia. These lessons underscore the significance of personalized approaches, emphasizing the need for practitioners to consider individual characteristics and contextual factors in their communication strategies.

As the orthodontic field continues to evolve, embracing innovative strategies for risk communication and informed consent becomes increasingly crucial. The study’s insights contribute significantly to the ongoing discourse on orthodontic risk communication, highlighting the necessity for a dynamic and adaptable approach. The findings emphasize that a one-size-fits-all model may not suffice in meeting the diverse needs of orthodontic patients worldwide. This research thus advocates for a paradigm shift toward a more personalized and culturally sensitive communication approach, fostering the highest standards of care and ensuring global patient satisfaction in orthodontic practices.

5. Limitations of the study

The study exhibits certain limitations that merit consideration. Firstly, the study’s exclusive focus on orthodontists in two European countries may constrain the generalizability of its findings to a more global context. As it is derived from our data, cultural and regional nuances play a significant role in shaping orthodontic practices, and a broader examination across diverse cultures and regions is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of risk communication practices.

Additionally, the substantial divergence in response rates between Slovakia (43.3%) and Greece (15,61%) prompts a nuanced exploration of survey methodologies and participant engagement, informed by the established best practices in questionnaire design. Studies highlight the critical impact of survey design on participant response rates [80,81]. In our context, the variation could be attributed, in part, to the intricate interplay of factors elucidated elsewhere [82–84]. These factors encompass respondent cognitive demands and strategies for coping with these demands, and the potential influence of survey length and question format. These factors might have affected our response rates. Furthermore, in the systematic review by Meyer et al. (2022) [85] a global perspective is offered, suggesting that healthcare professionals often exhibit lower response rates than patients. Our findings align with this trend, where in Slovakia, with its higher response rate, the case might indicate more favorable conditions for healthcare professionals’ participation when compared to Greece. Additionally, other studies emphasize the importance of targeted education and tailored survey design in influencing respondent attitudes and improving survey outcomes suggesting that the interplay between the two countries could be attributed to the need for more custom-made questions [86,87]. Moreover, other insights underscore the challenges in surveying specific professional groups, such as surgeons, requiring specialized approaches for optimal engagement [88,89]. The literature recommends considering diverse survey administration methods, which include in-person, postal, and online surveys, each with its own associated response rates [85,90]. Considering the complexity of factors affecting response rates, future research should employ a tailored approach, informed by the rich body of knowledge encapsulated by studies like this one. In person communication of the scope of the survey could also possibly provide more responses from Greek participants.

Factors such as real-time data tracking; immediate survey delivery; and low costs associated with online surveys might contribute to their increased prevalence but at the expense of lower response rates, as happened in our case and was suggested elsewhere [85]. It is conceivable that the overflow of email contact, as highlighted in the literature, [85] may have negatively impacted respondents’ willingness to participate in the survey potentially influencing the lower response rate that was observed in Greece. Finally, the disparity in response rates between Slovakia and Greece could be attributed to a combination of regional differences in participant engagement, survey administration methods, and the inherent challenges associated with healthcare professional surveys. Considering the global patterns already outlined [85], future survey initiatives should carefully evaluate and tailor their methodologies to optimize participant engagement and ensure representative response rates.

Additionally, the study highlighted the impact of socio-demographic parameters on risk communication but did not delve into the specific socio-demographic factors contributing to the observed differences. A more in-depth exploration of factors such as age, gender, and professional experience is warranted to elucidate their precise influence on orthodontists’ choices in risk communication. The study also suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic might have influenced risk communication practices, particularly concerning the transmission of infectious diseases. However, this aspect was not comprehensively explored, necessitating longitudinal studies to delve into the lasting effects and adaptations in orthodontic practices post-pandemic. Furthermore, while the study briefly touched upon the practical aspects of informed consent, it did not thoroughly examine preferred methods for optimal comprehensibility. Future research could explore effective strategies for presenting consent information, considering factors such as verbal review, visual aids, and the order of presentation. Lastly, a more extensive investigation into the ethical obligations of orthodontists in communicating potential risks, while incorporating patient feedback, and adapting communication approaches based on various factors could contribute to the development of a more comprehensive ethical framework in orthodontic care. Long-term studies assessing the impact of effective risk communication on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence, and overall orthodontic outcomes would also be instrumental in shaping best practices in orthodontic care.

6. Conclusions

This study illuminates the pivotal role of effective risk communication in orthodontic practice, demonstrating the acknowledgment of its significance by orthodontists in two European countries. The variations in risk communication practices, influenced by socio-demographic factors, underscore the need for standardized guidelines, that potentially could be crafted by national orthodontic societies. The study identifies critical risks, such as root resorption and occlusal changes, emphasizing their prioritization in the informed consent process. While recognizing the practical implementation of consent, it prompts future research to explore optimal methods for enhancing comprehensibility. The findings advocate for risk assessment becoming integral to orthodontic management, influencing not only treatment but also practice marketing. Ethical obligations call for consistent communication of potential risks, with patient feedback shaping the quality of services. Future endeavors should delve into the long-term impact of risk communication on patient outcomes; satisfaction and treatment adherence and address an orthodontic informed consent protocol for tailored communication approach for orthodontic patients thereby contributing to the continuous refinement of orthodontic care practices.

Author Contributions

TConceptualization, F.K. and M.A.; methodology, F.K., M.A., K.D., D.C., V.M. and J.L.; validation, M.A., V.M. and J.L.; formal analysis, F.K., M.A., K.D.; investigation, F.K., K.D. and M.A.; resources, M.A., D.C. and J.L.; data curation, V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.K., M.A., K.D., D.C., V.M. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, M.A., D.C., V.M. and J.L.; visualization, F.K. and M.A.; supervision, M.A.; project administration, M.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Authorization for the distribution of the study questionnaire was retrieved for Slovakia from the Slovak Orthodontic Society (committee decision on 22/9/2022) and from the Greek Orthodontic Society and the Greek Association for Orthodontic Study & Research (committee decision on 13/9/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study while submitting the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all colleagues from both countries that participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Guidelines and consent for participation

Dear orthodontists,

We extend our invitation to you to participate in a collaborative research study titled “A Professional Consensus on Orthodontic Risks: Communication Approach, Quality Assurance, and Educational Strategies”. This study is jointly conducted by the Department of Dental Professional Practice at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and Comenius University in Slovakia.

The primary objective of this research is to investigate the communication practices surrounding orthodontic treatment risks among professional orthodontists and orthodontic students, along with identifying related educational needs. Your voluntary participation is crucial for gaining insights that contribute to the improvement of communication approaches, quality assurance, and educational strategies in the field. Please note that your participation is entirely voluntary, and the questionnaire is designed to be anonymous, with no collection of personal information. We kindly request each participant to fill in the questionnaire only once. The estimated time to complete the questionnaire is approximately 15 minutes.

Rest assured that the information collected will be used exclusively for the purpose of this study and will be kept confidential. Your valuable contribution will significantly enhance our understanding of orthodontic risk communication.

Thank you in advance for your participation.

Sincerely,

The Research Team

Appendix B

The Questionnaire of the study

Consent declaration: I participate in this study completely voluntarily and I accept the use of the information I give in publications for scientific purposes. Yes/No

Part 1. Demographic Characteristics

Q1. Please specify your gender: Male Female Other

Q2. Please specify your age: up to 30, 31 – 40, 41 – 50, 51 – 60, 60 and above

Q3. Please specify the country: Greece Slovakia

Q4. What is your marital status: Single Married Divorced Other

Q5. Please enter the number of children you have, if any: 0, 1-2,3 or more

Q6. What is your highest degree in dentistry? Dental Degree MSc. PhD.

Q7. Do you have a degree in a science other than dentistry? Yes No

Q8. How many years have you been practicing orthodontics?

1-10 years 11-20 years 21-30 years 31 years and above

Q9. What is your professional status regarding orthodontics?

Clinic Owner, Employee in private practice, Hospital employee (public sector), University employee, Other

Q10. If you have your own orthodontic practice, how many employees do you have besides yourself? 0/none, 1, 2-3, 4 and above, I don’t own an office

Part 2

Please indicate on a 5-point scale the frequency of communicating the following events/risks to your orthodontic patients during the initial consultation. (1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, 5=always)

Q1. Do you mention the possibility of relapse of the orthodontic result after the treatment?

Q2. Do you state the total duration of the orthodontic treatment?

Q3. Do you mention the consequences of refusing the proposed orthodontic treatment?

Q4. Do you mention the possibility of discomfort/pain during orthodontic movements?

Q5. Do you mention the possibility of tooth root resorption?

Q6. Do you mention the possibility of tooth necrosis?

Q7. Do you mention the possibility of failure of the desired movement of some teeth?

Q8. Do you mention the possibility of periodontal damage, caries, hypocalcification if oral hygiene is not appropriate?

Q9. Do you mention the possibility of black triangles and other aesthetic problems (eg, midline non-coincidence)?

Q10. Do you mention the possibility that extractions will be needed during treatment?

Q11. Do you mention the possibility of taking additional x-rays?

Q12. Do you mention the possibility of finding idiopathic inability to erupt, inclusion, or ankylosis of teeth?

Q13. Do you mention the possibility of temporary undesired changes to the occlusion?

Q14. Do you mention the possibility of a temporary aggravation of the problem before the final surgical correction?

Q15. Do you mention the possibility of using a protective splint during sports activities with your patients?

Q16. Do you mention the possibility of difficulty in taking food?

Q17. Do you mention the possibility of speech difficulties?

Q18. Do you mention the possibility of sleep difficulties?

Q19. Do you mention the need to implement modified oral hygiene instructions?

Q20. Do you mention the possibility of not achieving an ideal result?

Q21. Do you state the duration of orthodontic treatment and the number of individual visits?

Q22. Do you mention the possibility of emergency visits due to practical problems (e.g. broken orthodontic appliance, loss of elastic ligature, broken brackets, excess wire, etc.)?

Q23. Do you mention the possibility of transmission of infectious diseases within the dental office (e.g. Covid-19)?

Q24. Do you mention the possibility of swallowing detached brackets or other orthodontic appliances?

Q25. Do you mention the possibility of allergic reactions to orthodontic materials?

Q26. Do you state the total cost of the orthodontic treatment?

Q27. Do you obtain written or digital consent from your patients or their patients’ parents/guardians?

Part 3

Q28. Do you repeat the process of information during the progress of orthodontic treatment? Yes/No

Q29. Patients are informed by:

me personally

the dental assistant

the secretary

other clinic staff

Q30. In your practice, you prioritize the information of:

Children

Parents/guardians

Adult patients

Elderly patients

Periodontal patients

Patients with specific general diseases (e.g. heart diseases)

Patients with severe aesthetic problems

Patients with severe functional problems

Patients who have a multidisciplinary treatment plan

Patients who will need extractions

All the above

None of the above

Q31. The time you spend in the initial information stage of your orthodontic patients is:

Q32. For the presentation of possible risks, you use:

Q33. Do you use your patient information process as a marketing tool for your practice?

on social media (Facebook, Instagram, etc.)

with email marketing

on the clinic’s website

in the waiting room

in information brochures

I am not interested in marketing my office

Other

Part 4

Please explain shortly your opinion

Q34. What are the main problems you have with communicating the risks of orthodontic treatment?

........................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Q35. What would help you better to communicate the risks of orthodontic treatment with your patients? (suggest actions at a personal and professional or association level)

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................

References

- Informed consent. Merriam Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/informed%20consent.

- Cocanour, C.S. Informed Consent-It’s more than a signature on a piece of paper. Am J Surg. 2017, 214, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira NC, Pacheco-Pereira C, Keenan L, Cummings G, Flores-Mir C. Informed consent comprehension and recollection in adult dental patients: A systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2016, 147, 605–619.e607. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadori, M.; Raadabadi, M.; Ravangard, R.; Baldacchino, D. Factors affecting dental service quality. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2015, 28, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, J.L.; Proffit, W.R. Communication in orthodontic treatment planning: bioethical and informed consent issues. Angle Orthod 1995, 65, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Antoniadou, M. Quality assurance of dental services. The health and well-being of dentists as the X-factor of the quality in the dental office. Tsiotras Eds, Athens, 2022.

- Antoniadou, M. Application of humanities and basic principles of coaching in health studies Tsiotras Eds, Athens, 2021.

- American Association of Orthodontics (AAO) Forms and releases. https://www2.aaoinfo.org/practice-management/legal-resource-center/forms-and-releases/.

- Naranjo, A.A.; Trivino, M.L.; Jaramillo, A.; Betancourth, M.; Botero, J.E. Changes in the subgingival microbiota and periodontal parameters before and 3 months after bracket placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006, 130, 275 e217-222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renkema, A.M.; Fudalej, P.S.; Renkema, A.A.; Abbas, F.; Bronkhorst, E.; Katsaros, C. Gingival labial recessions in orthodontically treated and untreated individuals: a case - control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2013, 40, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 11. Weltman, B, Vig, K.W.; Fields, H.W.; Shanker, S.; Kaizar, E.E. Root resorption associated with orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010, 137, 462–476, discussion 412A. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maaitah, E.F.; Adeyemi, A.A.; Higham, S.M.; Pender, N.; Harrison, J.E. Factors affecting demineralization during orthodontic treatment: a post-hoc analysis of RCT recruits. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011, 139, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrusio, C.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Blasi, A.; Leuci, S.; Adamo, D.; Nicolo, M. The effect of orthodontic treatment on periodontal tissue inflammation: A systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2018, 49, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cerroni, S.; Pasquantonio, G.; Condo, R.; Cerroni, L. Orthodontic Fixed Appliance and Periodontal Status: An Updated Systematic Review. Open Dent J. 2018, 12, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandall, N.A.; Hickman, J.; Macfarlane, T.V.; Mattick, R.C.; Millett, D.T.; Worthington, H.V. Adhesives for fixed orthodontic brackets. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018, 4, CD002282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Fida, M.; Gul, M. Decalcification and bond failure rate in resin modified glass ionomer cement versus conventional composite for orthodontic bonding: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Int Orthod. 2020, 18, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heymann, G.C.; Grauer, D. A contemporary review of white spot lesions in orthodontics. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2013, 25, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraundorf, E.C.; Araujo, E.; Ueno, H.; Schneider, P.P.; Kim, K.B. Speech performance in adult patients undergoing Invisalign treatment. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosvall, M.D.; Fields, H.W.; Ziuchkovski, J; Rosenstiel, S.F.; Johnston, W.M. Attractiveness, acceptability, and value of orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 2009; 135, 276 e271-212discussion 276-277. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, D.K.; Fields, H.W.; Johnston, W.M.; Rosenstiel, S.F.; Firestone, A.R.; Christensen, J.C. Orthodontic appliance preferences of children and adolescents. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 2010; 138, 698 e691-612discussion 698-699. [Google Scholar]

- Damasceno Melo, P.E.; Bocato, J.R.; de Castro Ferreira Conti, A.C.; Siqueira de Souza, K.R.; Freire Fernandes, T.M.; de Almeida, M.R. Effects of orthodontic treatment with aligners and fixed appliances on speech. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigante, M.; Spalj, S. Clinical predictors of metal allergic sensitization in orthodontic patients. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2022, 30, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, Z.J.; Gul, S.S.; Shaikh, M.S.; Abdulkareem, A.A.; Zafar, M.S. Incidence of Gingival Black Triangles following Treatment with Fixed Orthodontic Appliance: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 2022; 10, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, R.J.; Strauss, R.A.; Bridges-Poquis, A.; Peluso, A.R.; Lindauer, S.J. Moving an ankylosed central incisor using orthodontics, surgery and distraction osteogenesis. Angle Orthod. 2001, 71, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Konstantonis, D.; Anthopoulou, C.; Makou, M. Extraction decision and identification of treatment predictors in Class I malocclusions. Prog Orthod. 2013, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.D.; Littlewood, S.J. Retention in orthodontics. Br Dent J. 2015, 218, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, S.J.; Kandasamy, S.; Huang, G. Retention and relapse in clinical practice. Aust Dent J. 2017, 62 Suppl 1, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, V.N.; Ramachandra, S.S.; Dicksit, D.D.; Gundavarapu, K.C. Extraction protocols for orthodontic treatment: A retrospective study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2016, 7, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dowsing, P.; Murray, A.; Sandler, J. Emergencies in orthodontics. Part 1, Management of general orthodontic problems as well as common problems with fixed appliances. Dent Update 131-134, 137-140. 2015, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamani, I.I.; Makrygiannakis, M.A.; Bitsanis, I.; Tsolakis, A.I. Ingestion of orthodontic appliances: A literature review. J Orthod Sci. 2022 May 4;11,20. [CrossRef]

- Banakar, M.; Bagheri Lankarani, K.; Jafarpour, D.; Moayedi, S.; Banakar, M.H.; Mohammad Sadeghi, A. COVID-19 transmission risk and protective protocols in dentistry: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2020, 20, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo, A.A.; Triviño, M.L.; Jaramillo, A.; Betancourth, M.; Botero, J.E. Changes in the subgingival microbiota and periodontal parameters before and 3 months after bracket placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006 Sep;130,275.e17-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weltman, B.; Vig, K.W.; Fields, H.W.; Shanker, S.; Kaizar, E.E. Root resorption associated with orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010 Apr;137,462-76; discussion 12A. [CrossRef]

- Renkema, A.M.; Sips, E.T.; Bronkhorst, E.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M. A survey on orthodontic retention procedures in The Netherlands. Eur J Orthod. 2009 Aug;31,432-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishney, M. Potential risks of orthodontic therapy: a critical review and conceptual framework. Aust Dent J. 2017, 62 Suppl 1, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkaddour, A.; Bahije, L.; Bahoum, A.; Zaoui, F. Orthodontics and enamel demineralization: clinical study of risk factors. Int Orthod. 2014, 12, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jacox, L.A.; Little, S.H.; Ko, C.C. Orthodontic tooth movement: The biology and clinical implications. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018 Apr;34,207-214. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, F.; Al-Kheraif, A.A.; Romanos, E.B.; Romanos, G.E. Influence of orthodontic forces on human dental pulp: a systematic review. Arch Oral Biol. 2015 Feb;60,347-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maaitah, E.F.; Adeyemi, A.A.; Higham, S.M.; Pender, N.; Harrison, J.E. Factors affecting demineralization during orthodontic treatment: a post-hoc analysis of RCT recruits. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011 Feb;139,181-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Felippe, N.L.; Da Silveira, A.C.; Viana, G.; Smith, B. Influence of palatal expanders on oral comfort, speech, and mastication. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010 Jan;137,48-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ani, M.H.; Mageet, A.O. Extraction Planning in Orthodontics. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018 May 1;19,619-623. [PubMed]

- Chakravarthi, S.; Padmanabhan, S.; Chitharanjan, A.B. J Orthod Sci. 2012 Oct;1,83-7. [CrossRef]

- Leenen, R.L.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M.; Jagtman, B.A.; Katsaros, C. Nikkelallergie en orthodontie [Nickel allergy and orthodontics]. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2009, 116, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gölz, L.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Jäger, A. Nickel hypersensitivity and orthodontic treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2015, 73, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, S.; Suhani, J. Black gingival triangle in orthodontics: Its etiology, management and contemporary literature review. Saint’s Int Dent J.2020, 4,17-22. [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, S.J.; Kandasamy, S.; Huang, G. Retention and relapse in clinical practice. Aust Dent J. 2017 Mar;62 Suppl 1,51-57. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowsing, P.; Murray, A.; Sandler, J. Emergencies in orthodontics. Part 1, Management of general orthodontic problems as well as common problems with fixed appliances. Dent Update. 2015 Mar;42,131-4, 137-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff PM, Podsakoff NP. Construct Measurement and Validation Procedures in MIS and Behavioral Research: Integrating New and Existing Techniques. MIS Quarterly. 2011, 35,293–334.

- Jackson, S.A.; Marsh, H.W. Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The Flow State Scale. J Sport Exercise Psychol. 1996, 18, 17–35. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Hoza, B.; Pelham, W.E.; Rapoff, M.; Ware, L.; Danovsky, M.; Stahl, K.J. The development and validation of the Children’s Hope Scale. J Pediatric Psychol. 1997, 22, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J Vocation Beh 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Masoura, E.; Devetziadou, M.; Rahiotis, C. Ethical Dilemmas for Dental Students in Greece. Dent J (Basel). 2023 May 2;11,118. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Mangoulia, P.; Myrianthefs, P. Quality of Life and Wellbeing Parameters of Academic Dental and Nursing Personnel vs. Quality of Services. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Oct 21;11,2792. [CrossRef]

- Izadi, A.; Jahani, Y.; Rafiei, S.; Masoud, A.; Vali, L. Evaluating health service quality: using importance performance analysis. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2017 Aug 14;30,656-663. [CrossRef]

- Bernabe, E.; Sheiham, A.; de Oliveira, C.M. Impacts on daily perfor- mances related to wearing orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 482–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Popat, H.; Johnson, I.; Farnell, D.; Morgan, M.Z. Professional consensus on orthodontic risks: What orthodontists should tell their patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2021 Jan;159,41-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, E.S.; Yen, S.L. Informed Consent for Orthodontic Treatment: An Overview of Contemporary Materials and Techniques. J Amer Dent Assoc. 2014, 145, 439–442. [Google Scholar]

- Hancox, R.J.; Shelton, W.; Sutherland, M.; Magee, KP. Orthodontic informed consent: An overview. J World Fed Orthodont. 2014, 3, e129–e133. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Asokan, S.; John, J.; Geetha Priya, P.R. A Survey on the Practices of Orthodontists in Obtaining Informed Consent From Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Pharmacy Bioallied Sci. 2016,8(Suppl 1):S86-S90.

- Baskin, B.; Broder, H.L.; Gelbier, S. Consent and orthodontic treatment. Amer J Orthodont Dent Orthoped. 2000, 117, 560–562. [Google Scholar]

- Clementini, M.; Laino, L.; De Vivo, D.; Ferrara, E.; Lupi, S.M. Professional Responsibility in Orthodontics: Risk Management. Open Dent J. 2018, 12, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.K.; Abutayyem, H.; Kanwal, B.; Alswairki, H.J. Effect of COVID-19 on orthodontic treatment/practice- A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthod Sci. 2023 Apr 28;12,26. [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Tseroni, M.; Vorou, R.; Koutsolioutsou, A.; Antoniadou, M.; Tzoutzas, I.; Panis, V.; Tzermpos, F.; Madianos, P. Preparing dental schools to refunction safely during the COVID-19 pandemic: an infection prevention and control perspective. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021 Jan 31;15,22-31. [CrossRef]

- Tzoutzas, I.; Maltezou, H.C.; Barmparesos, N.; Tasios, P.; Efthymiou, C.; Assimakopoulos, MN.; Tseroni, M.; Vorou, R.; Tzermpos, F.; Antoniadou, M.; Panis, V.; Madianos, P. Indoor Air Quality Evaluation Using Mechanical Ventilation and Portable Air Purifiers in an Academic Dentistry Clinic during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Aug 23;18,8886. [CrossRef]

- Carr, K.M.; Fields, H.W.; Beck, F.M.; Kang, E.Y.; Kiyak, H.A.; Pawlak, C.E.; Firestone, A.R. Impact of verbal explanation and modified consent materials on orthodontic informed consent. Amer J Orthod Dent Orthop. 2012, 141, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, A.; Al-Diwani, H. What is the best method to ensure informed consent is valid for orthodontic treatment? A trial to assess long-term recall and comprehension. Evid Based Dent. 2022 Jun;23,52-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skulski, B.N.; Fields, H.W.; Johnston, W.M.; Robinson, F.G.; Firestone, A.; Heinlein, D.J. Rehearsal’s effect on recall and comprehension of orthodontic informed consent. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2021 Apr;159,e331-e341. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; McGrath, C.P.; Samman, N. Technology as a means to enhance orthodontic practice. Aust Orthod J. 2006, 22, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, M.; Cain, J. The Emerging Issue of Digital Empathy. Amer J Pharm Edu. 2016, 80, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashshur, R.L.; Shannon, G.W.; Krupinski, E.A. National telemedicine initiatives: essential to healthcare reform. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2009,15,600-610.

- Hollander, M.H.; de Leeuw, R.J. Towards a wearable oral robotic instrument for orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 2016, 38, 624–629. [Google Scholar]

- Kellar, KL. Informed Consent: A “Repetition” of the Principal Elements? Transfusion Medicine Reviews. 2009, 23, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Devetziadou, M.; Antoniadou, M. Branding in Dentistry: A Historical and Modern Approach to a New Trend. J Dent & Oral Disord. 2020, 6, 1130.

- Devetziadou M, Antoniadou M. Dental Patient’s Journey Map: Introduction to Patient’s Touchpoints. On J Dent Oral Health. 4, 2021. OJDOH.MS.ID.000593. 0005. [CrossRef]

- Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Whelan, T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Sci Med. 1997, 44, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Inter Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, V.A.; Carter, S.M.; Cribb, A.; McCaffery, K. Supporting patient autonomy: the importance of clinician-patient relationships. J Gen Inter Med. 2010, 25, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, E.J.; Emanuel, L.L. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992, 267, 2221–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, J. Health Care Decision Making by Couples: A Dyadic Perspective. Family Relations. 2008, 57, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, E.; Jacoby, A.; Thomas, L. Design and use of questionnaires: a review of best practice applicable to surveys of health service staff and patients. Health Technol Assess. 2001, 5, 1–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, G. The purpose, design and administration of a questionnaire for data collection. Radiography 2005, 11, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.W.; Reddy, S.; Durning, S.J. Improving response rates and evaluating nonresponse bias in surveys: AMEE Guide No. 102. Med Teach 2016, 38, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A. Response strategies for coping with the cognitive demands of attitude measures in surveys. Appl Cogn Psychol. 1991, 5, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A. Survey research. Annu Rev Psychol. 1999, 50, 537–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, V.; Maurice, M.D.; Benjamens, S.B.; Moumni, Mostafa E.; Lange, J.F.; Pol, R.A. Global Overview of Response Rates in Patient and Health Care Professional Surveys in Surgery: A Systematic Review. Annals Surg. 2022,275,p e75-e81. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Z.; Gültekin, K.E.; Demirtaş, O.K. Effects of targeted education for first-year university students on knowledge and attitudes about stem cell transplantation and donation. Exp Clin Transplant 2015, 13, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method--2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide.; 2011.

- Jones, D.; Story, D.; Clavisi, O. An introductory guide to survey research in anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care 2006, 34, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague, S.; Quigley, L.; Bhandari, M. Survey design in orthopaedic surgery: getting surgeons to respond. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009, 91 (suppl 3), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, P.J.; Roberts, I.; Clarke, M.J.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Wentz, R.; Kwan, I.; Cooper, R.; Felix, LM.; Pratap, S. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2009, 3(Art. No.: MR000008). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).