Submitted:

08 February 2024

Posted:

09 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Substrate Spectra

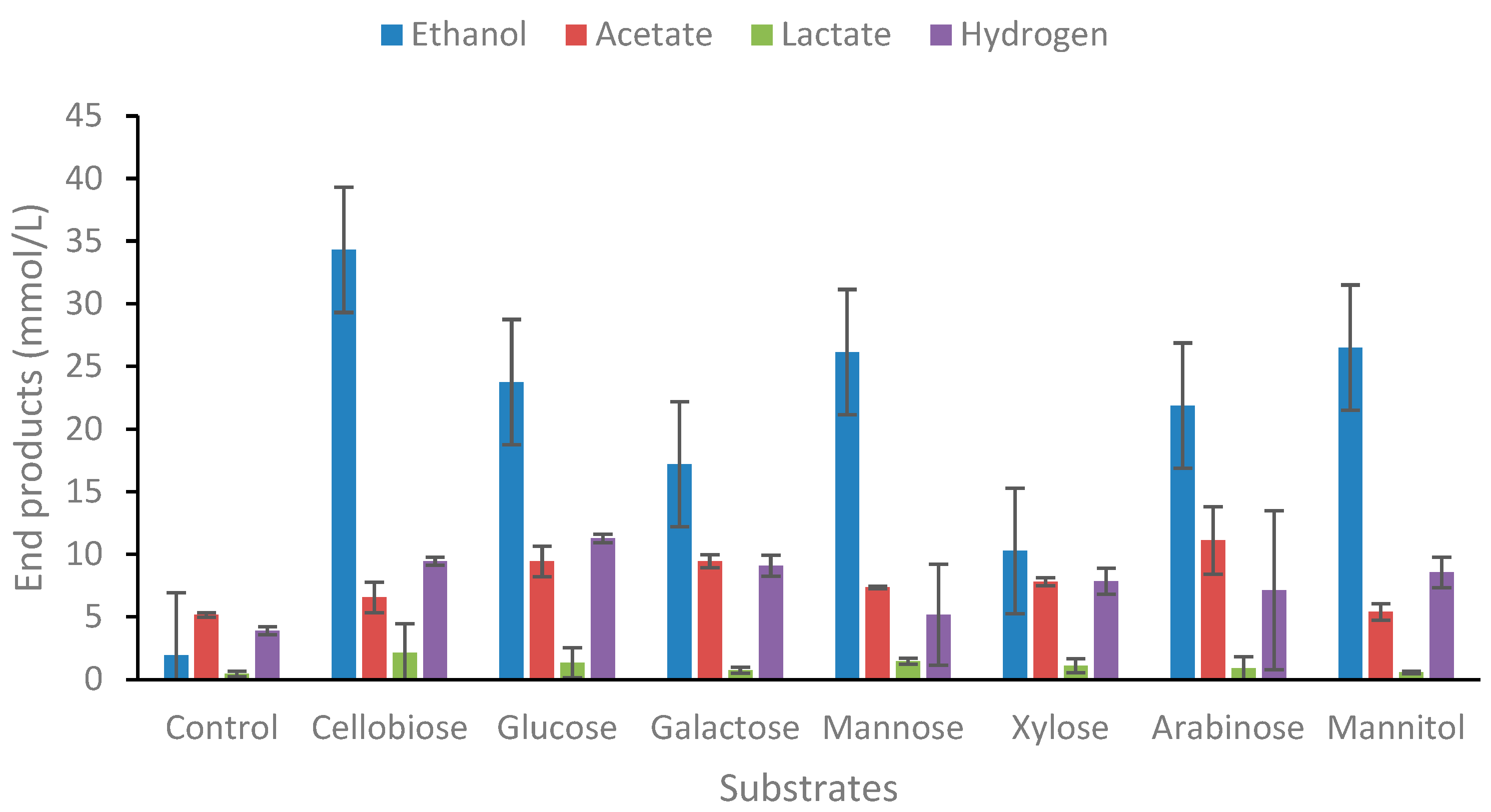

2.1.1. Degradation of Carbohydrates

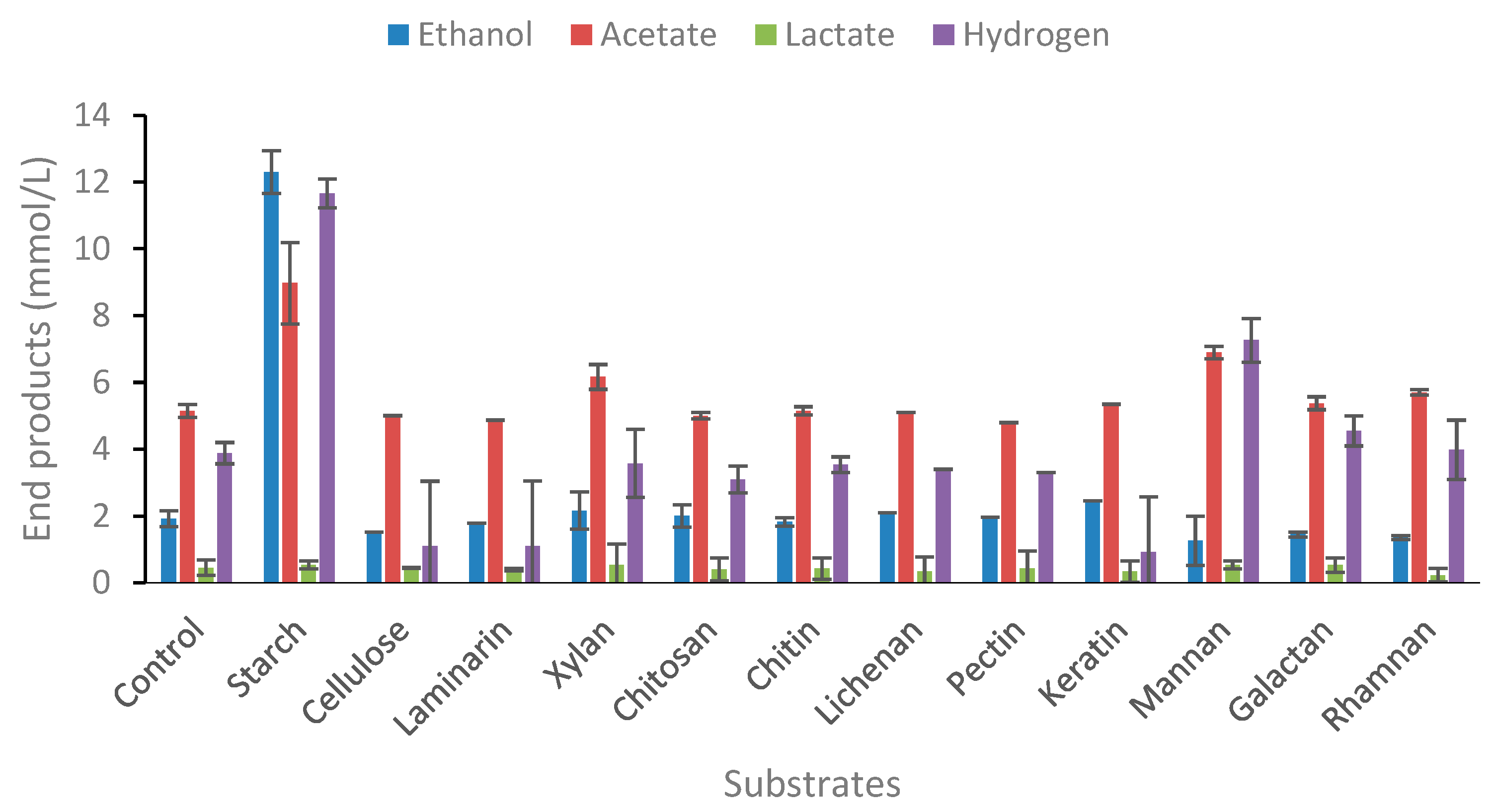

2.1.2. Degradation of Polymeric Carbohydrate Substrates

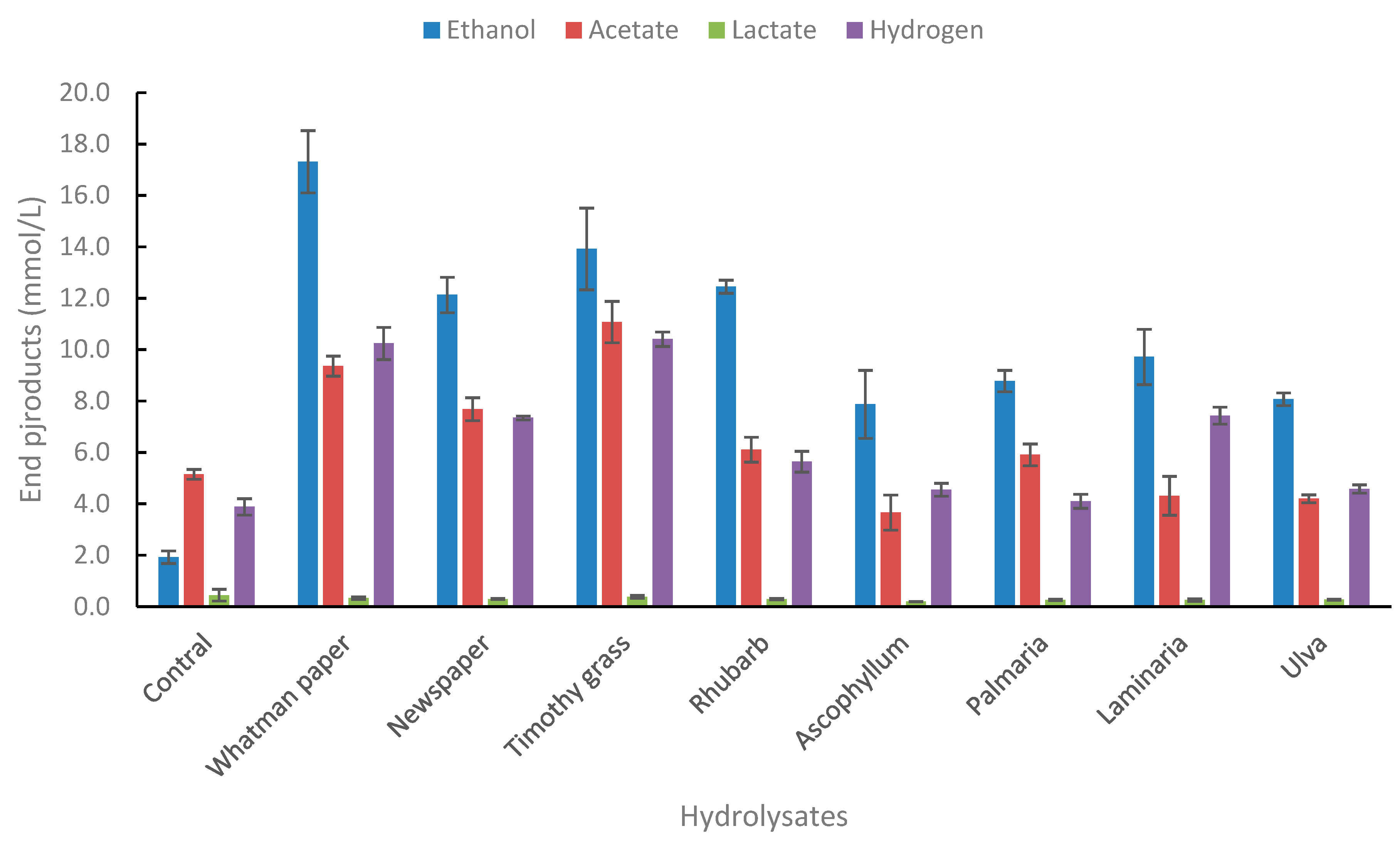

2.1.3. Degradation of Biomass Hydrolysates

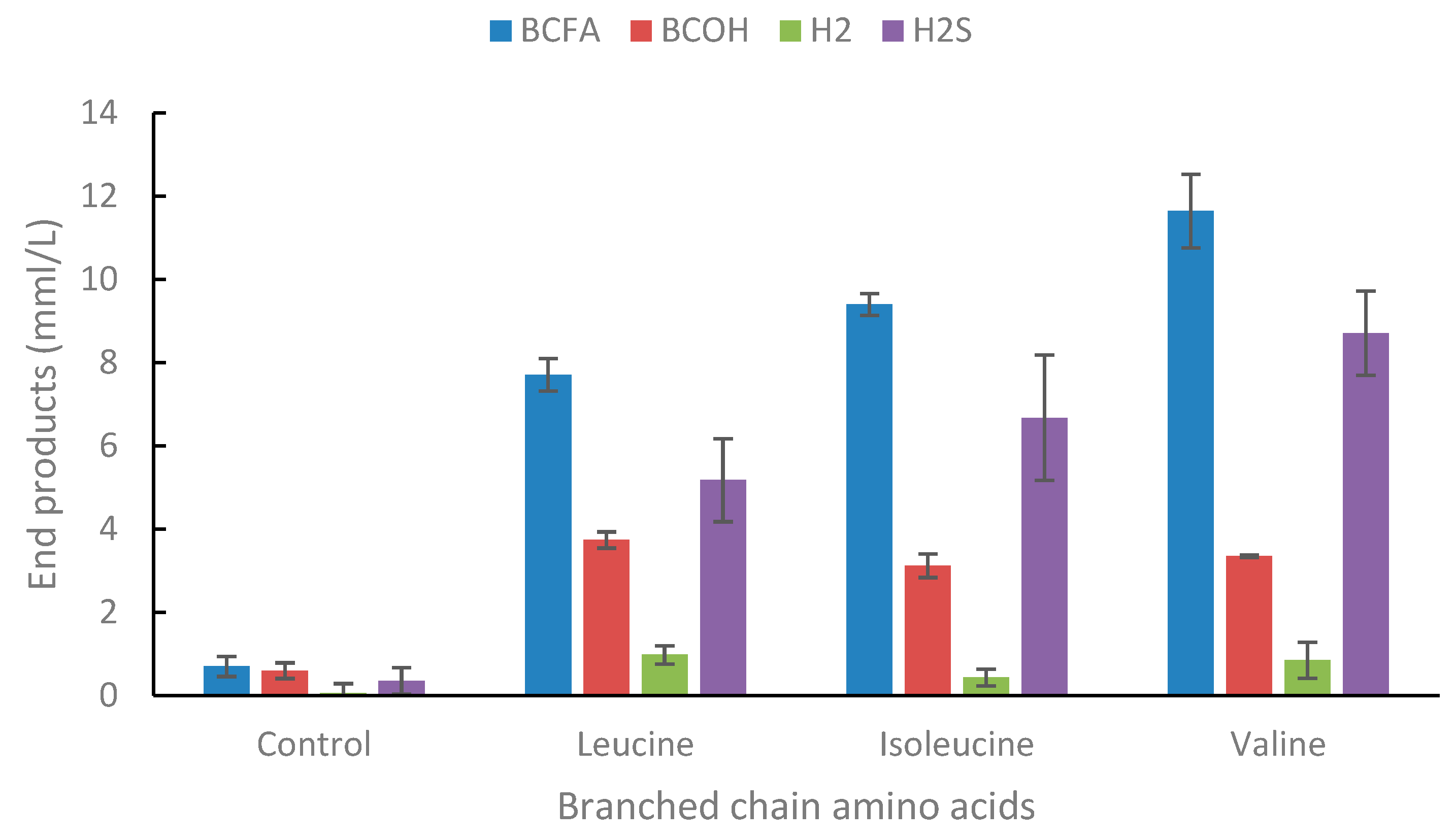

2.1.4. Degradation of Amino Acids

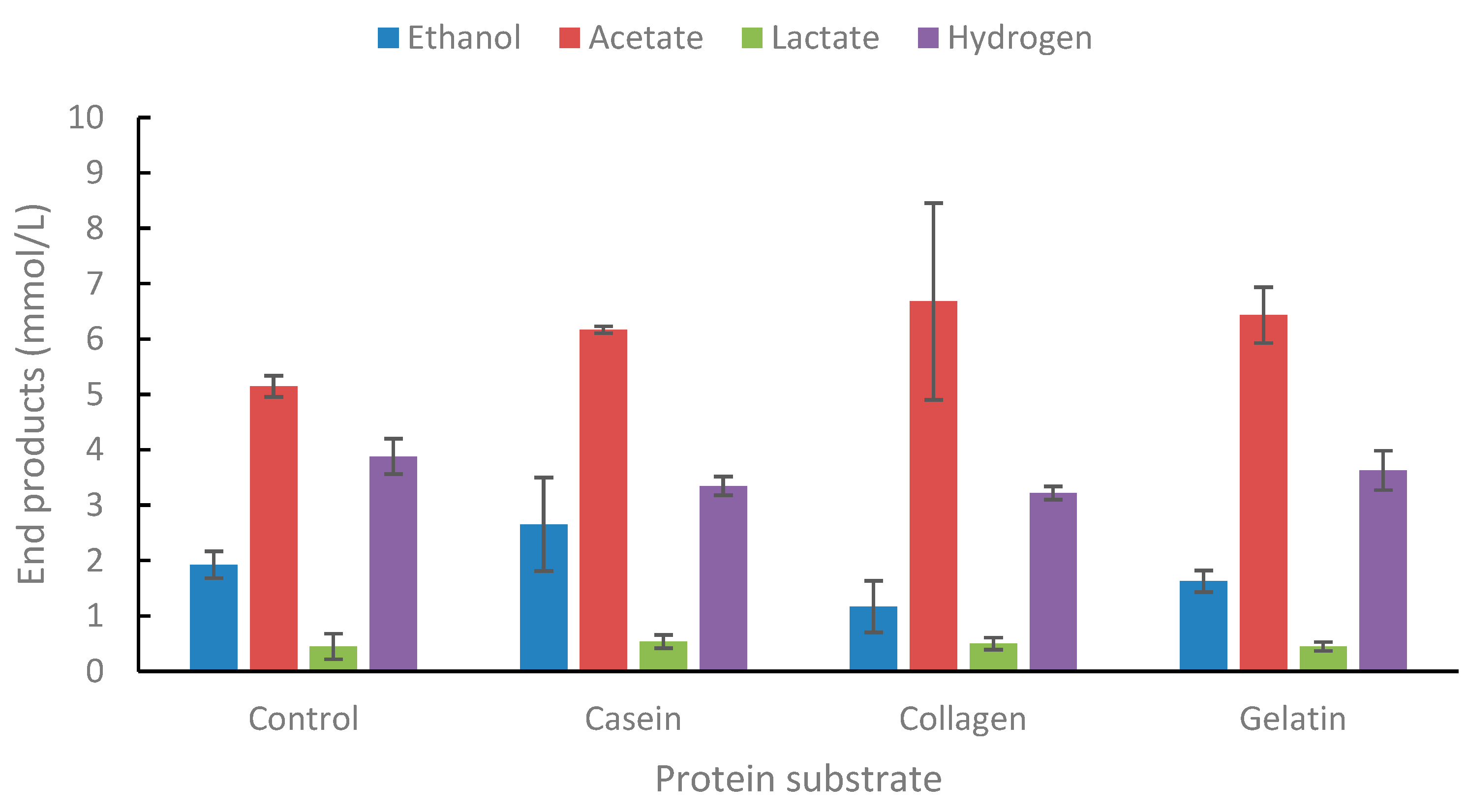

2.1.5. Degradation of Proteins

2.1.6. Conversion of fatty acids to alcohols

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Culture Medium and Preparation

3.3. Bacterial Strain

3.4. Substrate Utilization Spectrum

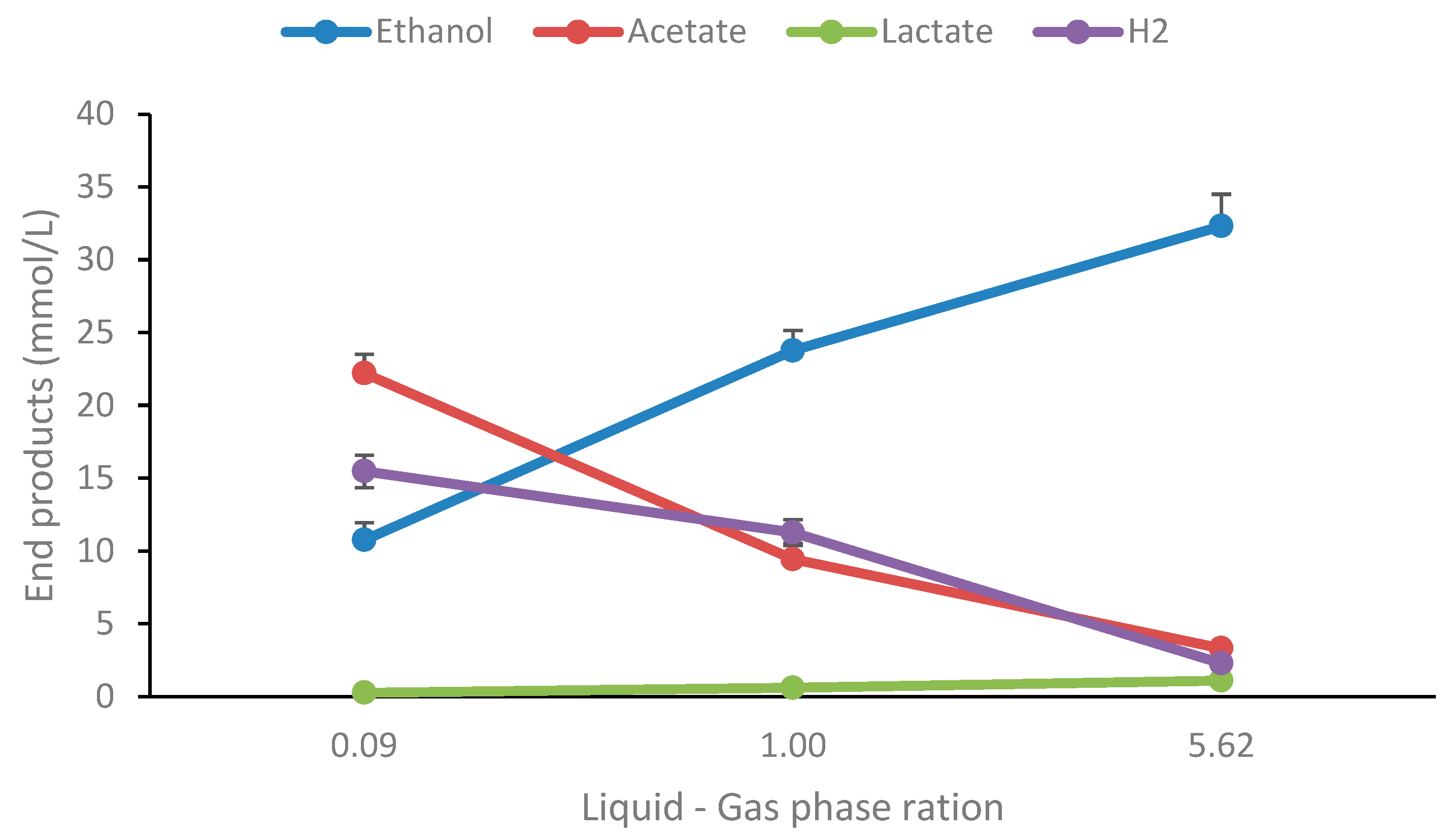

3.5. Influence of Liquid-Gas Phase Ratio

3.6. Analytical Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demain, A. Biosolutions to the energy problem. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biot. 2009, 36, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.P.; Eley, K.L.; Martin, S.; Tuffin, M.I.; Burton, S.G.; Cowan, D.A. Thermophilic ethanologenesis: future prospects for second-generation bioethanol production. Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scully, S.M.; Orlygsson, J. Recent Advances in Second Generation Ethanol Production by Thermophilic Bacteria. Energies 2015, 8, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn-Hagerdal, B.; Galbe, M.; Gorwa-Grauslund, M.F.; Liden, G.; Zacchi, G. Bioethanol - the future of tomorrow from the residues of today. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 12, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.S.; Dworjanyn, S. The potential of marine biomass for anaerobic biogas production; Wrown Estate: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco, S.; Stokes, J. Valorisation to biogas of macroalgal waste streams: A circular approach to bioproducts and bioenergy in Ireland. Chem. Pap. 2017, 71, 721–728. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegel, J.; Ljungdahl, L. Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus gen. nov., spec. nov., a new, extreme thermophilic, anaerobic bacterium. Arch. Microbiol 1981, 128, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, T.I.; Mikkelsen, M.J.; Ahring, B.K. Ethanol production from wet-exploded wheat straw hydrolysate by thermophilic anaerobic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter BG1L1 in a continuous immobilized reactor. Appl. Biochem. Biotech. 2008, 145, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, T.J.; Cubonova, L.; Reeve, J.N. Deletion of alternative pathways for reductant recycling of Thermococcus kodakarensis increases hydrogen production. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 81, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, G.L.; Stirrett, K.; Schut, G.J.; Yang, F.; Jenney, F.E.; Scott, R.A.; Adams, M.W.W.; Westpheling, J. Pyrococcus furiosus facilitates genetic manipulation: Construction of markerless deletions of genes encoding the two cytoplasmic hydrogenases. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2011, 77, 2232–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.; Chung, D.W.; Elkins, J.G.; Guss, A.M.; Westpheling, J. Metabolic engineering of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii yields increased hydrogen production from lignocellulosic biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2013, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, N.; Dipasquale, L.; d’Ippolito, G.; Panico, A.; Lens, P.N.L.; Esposito, G.; Fontana, A. Hydrogen and lactic acid synthesis by the wild-type and laboratory strain of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga neapolitana DSMZ 4359T under capnophilic lactic fermentation conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2017, 42, 16023–16030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Murphy, F.H. Propylene glycols. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 4th edition; Kroschwitz, J.I. (Ed.)., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 1994; Vol. 17, pp. 715–726. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, R.; Anand, P.; Saran, S.; Isar, J.; Agarwal, L. Microbial production and applications of 1,2-propanediol. Ind. J. Microbiol. 2010, 50, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.C.; Cooney, C.L. A novel fermentation: The production of ®-1,2-propanediol and acetol by Clostridium thermosaccharolyticum. Bioresource Technol. 1986, 4, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingvadottir, E.M.; Scully, S.M.; Orlygsson, J. Evaluation of the genus of Caldicellulosiruptor for production of 1,2-propanediol from methylpentoses. Anaerobe 2017, 47, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, M.; Lyon, D.; Rainey, F.A.; Wiegel, J. Caloramator viterbensis sp. nov., a novel thermophilic glycerol-fermenting bacterium isolated from a hot spring in Italy. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 2002, 52, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Scully, S.M.; Iloranta, P.; Myllymaki, P.; Orlygsson, J. Branched-chain alcohol formation by thermophilic bacteria within the genera of Thermoanaerobacter and Caldanaerobacter. Extremophiles 2015, 19, 809–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, J.R.; Laemthong, T.; Lewis, A.M.; Straub, C.T.; Adams, M.W.W.; Kelly, R.M. Extreme thermophiles as emerging metabolic platforms. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2019, 59, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackebrandt, E. The family Thermoanaerobacteraceae. In The Prokaryotes - Firmicutes and Tenericutes; Rosenberg, E., et al., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M.D.; Lawson, P.A.; Willems, A.; Cordoba, J.J.; Fernandezgarayzabal, J.; Garcia, P. The phylogeny of the genus Clostridium - proposal of 5 new genera and 11 new species combinations. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994. 44, 812–826.

- Larsen, L.; Nielsen, P. & Ahring, B.K. Thermoanaerobacter mathranii sp nov, an ethanol-producing, extremely thermophilic anaerobic bacterium from a hot spring in Iceland. Arch. Microbiol.

- Lee, Y.E.; Jain, M.K.; Lee, C.Y.; Lowe, S.E.; Zeikus, J.G. Taxonomic distinction of saccharolytic thermophilic anaerobes - description of Thermoanaerobacterium xylanolyticum gen-nov, sp-nov, and Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum gen-nov, sp-nov - reclassification of Thermoanaerobium brockii, Clostridium thermosulfurogenes, and Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum E100-69 as Thermoanaerobacter brockii comb-nov, Thermoanaerobacterium thermosulfurigenes comb-nov, and Thermoanaerobacter thermohydrosulfuricus comb-nov, respectively - and transfer of Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum 39E to Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1993, 43, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Slobodkin, A.I.; Tourova, T.P.; Kuznetsov, B.B.; Kostrikina, N.A.; Chernyh, N.A.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A. Thermoanaerobacter siderophilus sp. nov., a novel dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing, anaerobic thermophilic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1999, 49, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacis. L.S.; Lawford, H.G. Ethanol production from xylose by Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus in batch and continuous culture. Arch. Microbiol. 1988, 150, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, A.; Donmez, S. Effect of zinc on ethanol production by two Thermoanaerobacter strains. Process Biochem. 2009, 41, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyenwoke, R.U.; Kevbrin, V.V.; Lysenko, A.M.; Wiegel, J. Thermoanaerobacter pseudethanolicus sp. nov., a thermophilic heterotrophic anaerobe from Yellowstone National Park. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2007, 57, 2191–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitschler, L.; Kuntz, M.; Langschied, F.; Basen, M. Thermoanaerobacter species differ in their potential to reduce organic acids to their corresponding alcohols. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2018, 102, 8465–8476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brynjarsdottir, H.; Wawiernia, B.; Orlygsson, J. Ethanol production from sugars and complex biomass by Thermoanaerobacter AK5: The effect of electron-scavenging systems on end-product formation. Energ. Fuel 2012, 26, 4568–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingvadottir, E.M.; Scully, S.M.; Orlygsson, J. Production of (S)-1,2-prpanediol from rhamnose using the moderate thermophilic Clostridium strain AK1. Anaerobe 2018, 54, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaras, N.E.; Etzel, M.R.; Cameron, D.C. Conversion of sugars to 1,2-propanediol by Thermoanaerobacterium thermosaccharolyticum HG-8. Biotechnol. Progr. 2001, 17, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chades, T.; Scully, S.M.; Ingvadottir, E.M.; Orlygsson, J. Fermentation of Mannitol Extracts From Brown Macro Algae by Thermophilic Clostridia. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I.D.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, C.L.; Romanek, C.S.; Rohde, M.; Wiegel, J. Thermoanaerobacter uzonensis sp. nov., an anaerobic thermophilic bacterium isolated from a hot spring within the Uzon Caldera, Kamchatka, Far East Russia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 2565–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzak, T.; Levin, D.B.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R. End-product induced metabolic shifts in Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405. Appl. Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011, 2011. 92, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, T.J.; Zhang, X.; Henrissat, B.; Spicer, B.; Tydzak, T.; Krokhin, O.V.; Fristensky, B.; Levin, D.B.; Sparling, R. Genomic evaluation of Thermoanerobacter spp. for the construction of designer co-cultures to improve lignocellulosic biofuel production. PLoS ONE 2023, 8, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Riessen, S.; Antranikian, G. Isolation of Thermoanaerobacter keratinophilus sp. nov., a novel thermophilic, anaerobic bacterium with keratinolytic activity. Extremophiles 2001, 5, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgieva, T.I.; Ahring, B.K. Evaluation of continuous ethanol fermentation of dilute-acid corn stover hydrolysate using thermophilic anaerobic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter BG1L1. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2007, 77, 61–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almarsdottir, A.R.; Sigurbjornsdottir, M.A.; Orlygsson, J. Effect of various factors on ethanol yields from lignocellulosic biomass by Thermoanaerobacterium AK 17. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaparaju, P.; Serrano, M.; Thomsen, A.B.; Kongjan, P.; Angelidaki, I. Bioethanol, biohydrogen and biogas production from wheat straw in a biorefinery concept. Bioresource Technol. 2008, 100, 2562–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beluhan, S.; Mihajlovski, K.; Santek, B.; Santek, M.I. The production of bioethanol from lignocellulosic biomass: Pretreatment methods, fermentation, and downstream processing. Energies 2023, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, A.F.; Karagöz, P.; Karakashev, D.; Angelidaki, I. Extreme thermophilic ethanol production from rapeseed straw: Using the newly isolated Thermoanaerobacter pentosaceus and combining with Saccharomyces cerevisae in a two-step process. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 1574–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.J.; Xin, F.X.; Lu, J.S.; Dong, W.L.; Zhang, W.M.; Zhang, M.; Wu, H.; Ma, J.F.; Jiang, M. State of the art review of biofuels production from lignocellulose by thermophilic bacteria. Bioresource Technol. 2017, 245, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuliani, L.; Serpico, A.; Di Simone, M.; Frison, N.; Fusco, S. Biorefinery gets hot: Thermophilic enzymes and microorganisms for second generation bioethanol production. Processes 2021, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.T.X.; Tan, I.S.; Foo, H.C.Y.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, S.; Lee, K.T. Advancement of biorefinery-derived platform chemicals from macroalgae: a perspective for bioethanol and lactic acid. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, S.; Ueda, M. Utilization of macroalgae for the production of bioactive compounds and bioprocesses using microbial biotechnology. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadharsini, P.; Dawn, S.S.; Arun, J.; Ranjan, A.; Jayaprabakar, J. Recent advances in conventional and genetically modified macroalgal biomass as substrates in bioethanol production: a review. Biofuels UK. 2023, 2023. 14, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.Z; Li, Y.P.; Yang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, P.Y.; Wong, A.C.Y.; Hsieh, Y.S.Y.; Wang, D.M. Recent advances in bioutilization of marine macroalgae carbohydrates: Degradation, metabolism, and fermentation. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2022, 2022. 70, 1438–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Hansen, J.H.; Bjerre, A.B. Integrated bioethanol and protein production from brown seaweed Laminaria digitata. Bioresource. Technol. 2015, 197, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Li, P.; Lee, J.; Ryu, H.J.; Oh, K.K. Ethanol production from Saccharina japonica using an optimized extremely low acid pretreatment followed by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation. Bioresource Technol. 2013, 127, 127,119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, L.; Wang, P.; Mou, H. Study on saccharification techniques of seaweed wastes for the transformation of ethanol. Renew. Energ 2011, 36, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.J.; Li, H.; Jung, K.; Chang, H.N.; Lee, P.C. Ethanol production from marine algal hydrolysates using Escherichia coli KO11, Bioresource. Technol. 2011, 10, 7466–7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moenaert, A.; Lopez-Contreras, A.M.; Budde, M.; Allahgholi, L.; Xiaoru, H.; Bjerre, A.-B.; Orlygsson, J.; Karlsson, E.N.; Fridjonsson, O.H.; Hreggvidsson, G.O. Evaluation of Laminaria digitata hydrolysate for the production of bioethanol and butanol by fermentation. Fermentation 2023, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickland, L.H. CCXXXII. Studies in the metabolism of the strict anaerobes (genus Clostridium). The chemical reactions by which Cl. sporogenes obtains its energy. Biochem. J. 1934, 28, 1746–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deklevat, M.L.; Dasgupta, B.R. Purification and characterization of a protease from Clostridium botulinum Type A that nicks single-chain type A botulinum neurotoxin into the Di-Chain form. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 2498–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsden, S.R.; Hilton, M.G. The end products of metabolism of aromatic amino acids by clostridia. Arch. Microbiol. 1976, 107, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scully, S.M. Amino acid and related catabolisms of Thermoanaerobacter species. PhD thesis. University of Iceland. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elsden, S.R.; Hilton, M.G. Volatile acid production from threonine, valine, leucine and isoleucine by clostridia. Arch. Microbiol. 1978, 117, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laanbroek, H.H.; Smit, A.J.; Nulend, G.K.; Veldkamp, H. Competition for glutamate between specialized and versatile Clostridium species. Arch. Microbiol. 1979, 66, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toda, Y.; Saiki, T.; Uozumi, T.; Beppu, T. Isolation and characterization of protease-producing, thermophilic, anaerobic bacterium, Thermobacterides leptospartum sp. nov. Agr. Biol. Chem. 1988, 52, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardeau, M.-L.; Patel, B.K.C.; Magot, M.; Ollivier, B. Utilization of serine, leucine, isoleucine, and valine by Thermoanaerobacter brockii in the presence of thiosulfate or Methanobacterium sp. as electron acceptors. Anaerobe 1997, 3, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scully, S.M.; Orlygsson, J. Branched-chain alcohol formation from branched-chain amino acids by Thermoanaerobacter brockii and Thermoanaerobacter yonseiensis. Anaerobe. 2014, 30, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, G.; Smit, B.A.; Engels, W.J.M. Flavour formation by lactic acid bacteria and biochemical flavor profiling of cheese products. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, S.M.; Orlygsson, J. Branched-chain amino acid catabolism of Thermoanaerobacter strain AK85 and the influence of culture conditions on branched-chain alcohol formation. Amino acids 2019, 51, 1039–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, S.M.; Orlygsson, J. Branched-chain amino acid catabolism of Thermoanaerobacter pseudethanolicus reveals potential route to branched-chain alcohol formation. Extremophiles. 2020, 24, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faudon, C.; Fardeau, M.L.; Heim, J.; Patel, B.; Magot, M.; Ollivier, B. Peptide and amino acid oxidation in the presence of thiosulfate by members of the genus Thermoanaerobacter. Curr. Microbiol. 1995, 31, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, S.M.; Brown, A.E.; Mueller-Hilger, Y.; Ross, A.B.; Orlygsson, J. Influence of culture conditions on the bioreduction of organic acids to alcohols by Thermoanaerobacter pseudethanolicus. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlygsson, J.; Baldursson, S.R.B. Phylogenetic and physiological studies of four hydrogen-producing thermoanareobes. Iceland Agr. Sci. 2007, 20, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hungate, R.E. A roll tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes. In Methods in microbiology; Norris, J.R., Ribbons, D.W. (eds)., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1969; vol 3B, pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K.A.C.C. A simple colorimetric assay for muramic acid and lactic acid. Appl. Biochem. Biotech. 1996, 56, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, J.D. Spectrophotometric determination of hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. Limnol Oeanogr. 1969, 14, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).