Submitted:

15 December 2023

Posted:

18 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analysis

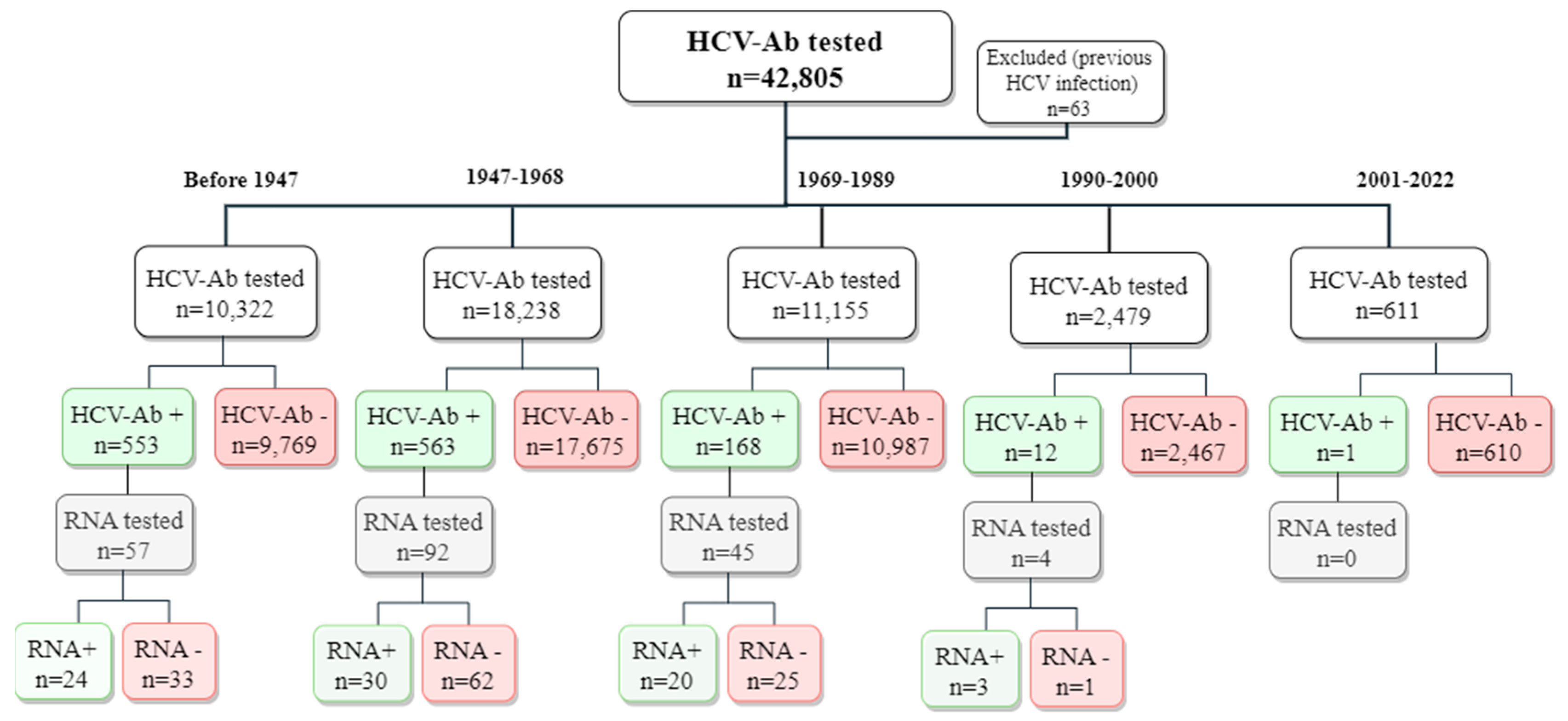

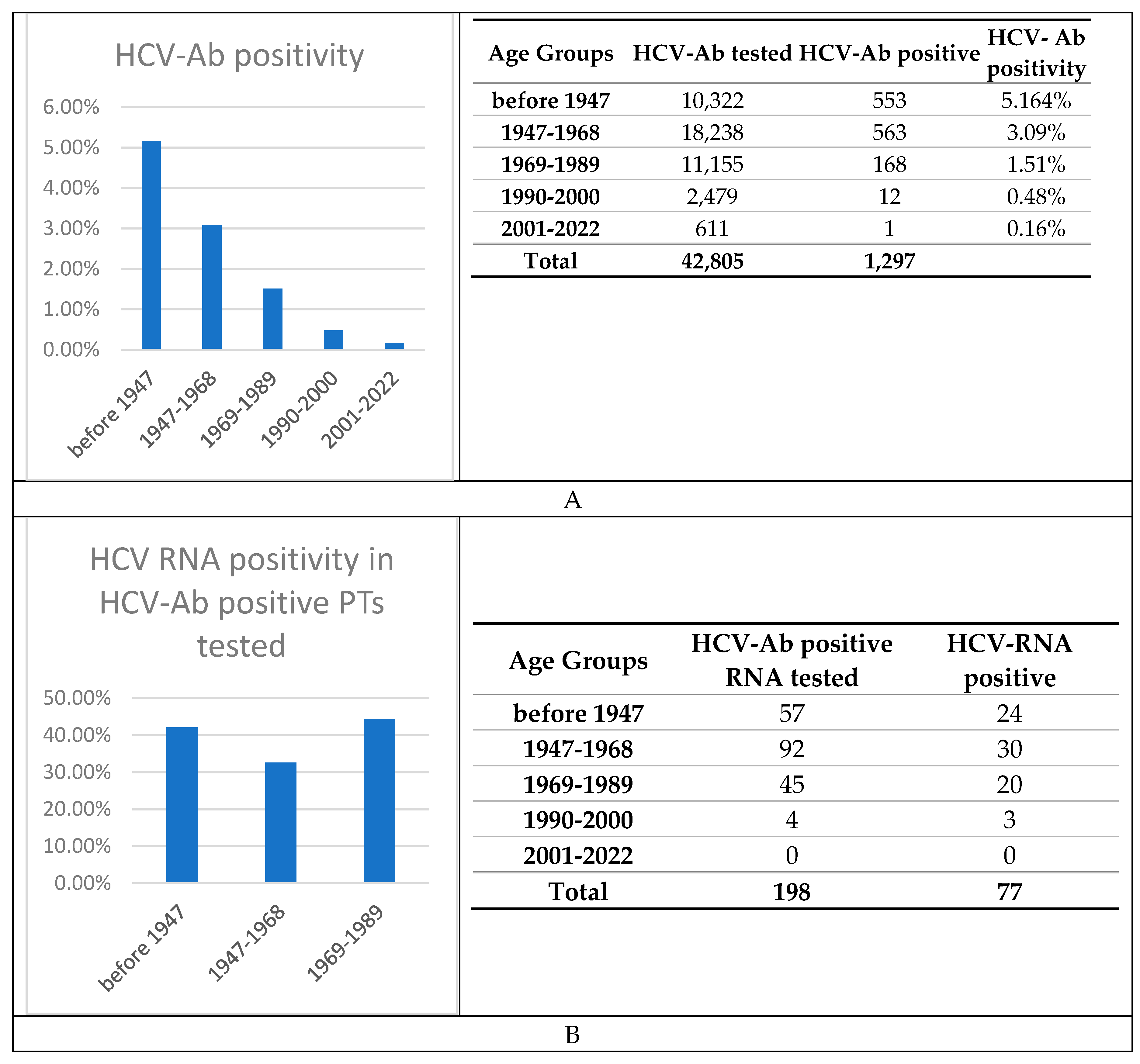

3. Results

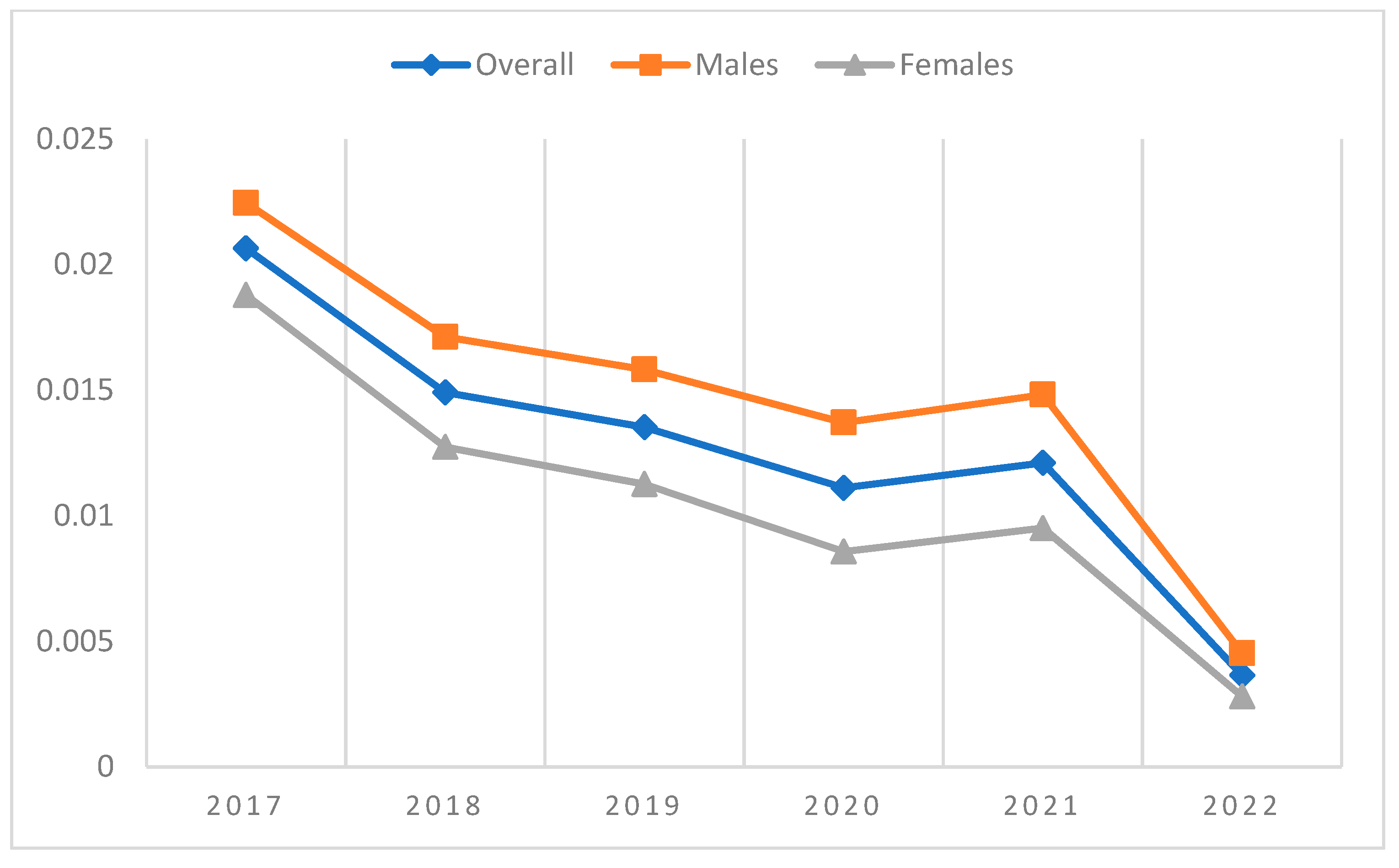

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| Overall | Incident cases | 335 | 279 | 261 | 190 | 184 | 33 |

| Patients at risk | 16,468 | 18,843 | 19,440 | 17,278 | 15,443 | 9,046 | |

| Incidence proportion | 2.03% | 1.48% | 1.34% | 1.10% | 1.19% | 0.36% | |

| Males | Incident cases | 184 | 159 | 151 | 115 | 111 | 20 |

| Patients at risk | 8325 | 9343 | 9671 | 8533 | 7557 | 4414 | |

| Incidence proportion | 2.21% | 1.70% | 1.56% | 1.35% | 1.47% | 0.45% | |

| Females | Incident cases | 151 | 120 | 110 | 75 | 73 | 13 |

| Patients at risk | 8143 | 9500 | 9769 | 8745 | 7886 | 4632 | |

| Incidence proportion | 1.85% | 1.26% | 1.13% | 0.86% | 0.93% | 0.28% |

4. Discussion

List of Abbreviations

| HCVAb | HCV-antibody; |

| HCOs | health-care organizations; |

| EMRs | electronic medical records |

| PTs | patients; |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase; |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase; |

| GGT | gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase; |

| SD | standard deviation; |

References

- Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(5):396-415. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Combating Hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Kondili LA, Andreoni M, Alberti A, et al. A mathematical model by route of transmission and fibrosis progression to estimate undiagnosed individuals with HCV in different Italian regions. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022;22(1):58. [CrossRef]

- WHO: Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021, 2016-2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/han-dle/10665/246177.

- Kondili LA, Gamkrelidze I, Blach, S, et al. Optimization of hepatitis C virus screening strategies by birth cohort in Italy. Liver Int. 2020;40(7):1545–1555. [CrossRef]

- Kondili LA, Aghemo A, Andreoni M, et al. Milestones to reach Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) elimination in Italy: From free-of-charge screening to regional roadmaps for an HCV-free nation. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022;54(2):237–242. [CrossRef]

- Rassen JA, Bartels DB, Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Murk W. Measuring prevalence and incidence of chronic conditions in claims and electronic health record databases. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;11:1-15. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for disease prevention and control (ECDC). Systematic review on hepatitis B and C prevalence in the EU/EEA. Stockholm: ECDC. Nov 2016.

- European Centre for disease prevention and control ((ECDC). Hepatitis B and C in the EU neighbourhood: prevalence burden of disease and screening policies. Stockolm: ECDC; 2010.

- European Centre for disease prevention and control (ECDC). Annual epidemiological report 2020.

- Stroffolini, T, Menchinelli, M, Taliani, G, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in a small central Italian town: Lack of evidence of parenteral exposure. Ital. J. Gastroenterol. 1995;27(5):235–238.

- Guadagnino, V, Stroffolini, T, Rapicetta M, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in the general population: A community-based survey in southern Italy. Hepatology 1997;26(4):1006–1011. [CrossRef]

- Kondili L. L’infezione cronica da virus dell’epatite C (HCV) in Lombardia. Infez. Med. 2021, S2.

- Di Stefano R, Stroffolini T, Ferraro D, et al. Endemic hepatitis C virus infection in a Sicilian town: Further evidence for iatrogenic transmission. J. Med. Virol. 2002;67(3): 339–344. [CrossRef]

- Rosato V, Kondili LA, Nevola R, et al. Elimination of hepatitis C in Southern Italy: A model of HCV screening and linkage to care among hospitalized patients at different hospital divisions. Viruses 2022;14(5):1096. [CrossRef]

- Roshanshad R, Roshanshad A, Fereidooni R, Hosseini-Bensenjan M. COVID-19 and liver injury: Pathophysiology, risk factors, outcome and management in special populations. World J Hepatol. 2023;15(4):441-459. [CrossRef]

- Nawghare P, Jain S, Chandnani S, et al. Predictors of severity and mortality in chronic liver disease patients with COVID-19 during the second wave of the pandemic in India. Cureus. 2022;14(1):e20891. [CrossRef]

- Eijsink JFH, Al Khayat MNMT, Boersma C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis C virus screening, and subsequent monitoring or treatment among pregnant women in the Netherlands. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(1):75-88. [CrossRef]

- McCormick CA, Domegan L, Carty P, et al. Routine screening for hepatitis C in pregnancy is cost effective in a large urban population in Ireland: a retrospective study. BJOG. 2021;129(2):322-327. [CrossRef]

- Ward Z, Mafirakureva N, Stone J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of mass screening for hepatitis C virus among all inmates in an Irish prison. Int J Drug Policy 2021;96:103394. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Z, Scott N, Al-Kurdi D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of strategies to improve HCV screening, linkage-to-care and treatment in remand prison settings in England. Liver Int. 2020 ;40(12):2950-2960. [CrossRef]

- Coretti S, Romano F, Orlando V, et al. Economic evaluation of screening programs for hepatitis C virus infection: evidence from literature. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2015; 8:45-54. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri M, Coretti S, Gasbarrini A, Cicchetti A. Economic assessment of an anti-HCV screening program in Italy. Value Health. 2013;16(6):965-972. [CrossRef]

- Kondili LA, Gamkrelidze I, Blach S et al; PITER collaborating group. Optimization of hepatitis C virus screening strategies by birth cohort in Italy. Liver Int. 2020;40(7):1545-1555. [CrossRef]

- Coppola C, Kondili LA, Staiano L, et al. Hepatitis C virus micro-elimination plan in Southern Italy: The "HCV ICEberg" project. Pathogens 2023; 12(2):195. [CrossRef]

- Morisco F, Loperto I, Stroffolini T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of HCV infection in a metropolitan area in southern Italy: Tail of a cohort infected in past decades. J. Med. Virol. 2017;89(2):291–297. [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio R, Rizzardini G, Puoti M, et al. Implementation of HCV screening in the 1969-1989 birth-cohort undergoing COVID-19 vaccination. Liver Int. 2022; 42(5):1012-1016. [CrossRef]

| Birth cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall | Before 1947 | 1947-1968 | 1969-89 | 1990-2000 | 2001-2022 |

| Number | 42,805 | 10,322 | 18,238 | 11,155 | 2,479 | 611 |

| Age | 57.8 (± 18) | 78.9 (± 4.7) | 62.5 (± 6.46) | 40.1 (± 6.29) | 25.6 (± 3.45) | 12.1 (± 6.62) |

| Males | 22,141 (52) | 6,179 (60) | 11,103 (61) | 3,856 (35) | 712 (29) | 291 ≡(48) |

| AST levels, IU/L | 50.1 (± 373) | 50 (± 324) | 52.9 (± 422) | 43.4 (± 219) | 39.6 (± 201) | 56.4 (± 228) |

| ALT levels, IU/L | 44.3 ± 197 | 38.1 (± 158) | 42.3 (± 167) | 49.2 (± 230) | 42.2 (± 166) | 59.7 (± 163) |

| PLTs count, x109/L | 232 (± 84.8) | 218 (± 85.8) | 233 (± 85.3) | 242 (± 80.3) | 239 (± 78.6) | 268 (± 119) |

| GGT levels, IU/L | 61.6 (± 149) | 58.8 (± 124) | 65.9 (± 157) | 55.5 (± 123) | 36.9 (± 65.7) | 32.9 (± 64.1) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.88 (± 1.69) | 0.912 (± 1.76) | 0.975 (± 2.02) | 0.754 (± 1.35) | 0.638 (± 0.601) | 0.573 (± 0.702) |

| ALP levels, IU/L | 91.4 (± 97.4) | 92.9 (± 102) | 95.4 (± 108) | 78.4 (± 74.3) | 68 (± 47.1) | 176 (± 109) |

| Characteristics | Overall | Before 1947 | 1947-68 | 1969-89 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 1,297 | 553 | 563 | 168 |

| Age | 66.7 (± 14.5) | 79.7 (± 4.9) | 62.1 (± 6.74) | 42.7 (± 6.09) |

| Males | 747 (57.6) | 282 (51) | 356 (63.2) | 103 (61.3) |

| AST levels, IU/L | 75.7 (± 602) | 80.9 (± 826) | 77 (± 400) | 57.5 (± 117) |

| ALT levels, IU/L | 52.3 (± 193) | 45.2 (± 239) | 54 (± 149) | 71.6 (± 157) |

| PLTs count, 109/L | 196 (± 91.3) | 186 (± 87.1) | 195 (± 89.5) | 225 (± 101) |

| GGT levels, IU/L | 70.3 (± 123) | 55.4 (± 95.5) | 83 (± 138) | 86.5 (± 153) |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.08 (± 2.19) | 0.994 (± 2.25) | 1.13 (± 1.94) | 1.26 (± 2.8) |

| ALP levels, IU/L | 94.7 (± 87.8) | 89.6 (± 57.6) | 97.6 (± 97.7) | 103 (± 134) |

| Patients | % of Cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age | 59.3 (± 18.6) | 77 | 100 |

| Males | - | 52 | 68 | |

| Females | - | 25 | 32 | |

| Biochemistry | AST levels, IU/L | 89.8 (± 185) | 72 | 94 |

| ALT levels, IU/L | 119 (± 233) | 72 | 94 | |

| Alkaline phosphatase levels, IU/L | 101 (± 69.1) | 56 | 73 | |

| GGT levels, IU/L | 108 (± 153) | 61 | 79 | |

| Platelets count x109/L | 192 (± 79.1) | 76 | 99 | |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.15 (± 2.38) | 66 | 86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).