1. Introduction

Uterine fibroids (UFs) are the most common benign neoplasm affecting women of reproductive age [

1]. They are the leading cause of hysterectomy in the US and worldwide and are a source of significant socioeconomic burdens [

1]. Black women are disproportionately affected by UFs, having a higher disease prevalence, earlier onset of disease, and more severe symptoms and disease progression [

2]. This disproportionate burden of UFs and other female health conditions is increasingly understood in a framework of health inequity and the social and structural drivers of health [

3]. Well established risk factors that may contribute to the high prevalence of UFs in Black individuals include socioeconomic status, adverse environmental exposures, and experiences that increase chronic stress [

4,

5]. Each of these factors are believed to converge to increase inflammation within the uterine myometrium resulting in somatic mutations (such as Med12) that transform normal myometrium stem cells and lead to UF tumor formation [

6].

In addition, many lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors, such as BMI, alcohol use, income, and occupation correlate closely with neighborhood characteristics e.g., access to healthy food and healthcare, exposure to environmental pollutants, and concentrated poverty [

5,

6]. Neighborhood poverty has been widely studied and is identified as a possible determinant of UF prevalence [

7,

8]. Poor and disenfranchised neighborhoods are often characterized by high crime rates, food insecurity, and other important social determinants of health [

9,

10,

11]. Lastly, while respiratory and cardiovascular diseases are most often linked to air pollution, recent studies have shown that air pollution is positively associated with risk of gynecological diseases [

12,

13] and exposure to air pollutants such as ozone and PM 2.5 may contribute to the racial disparities in UF incidence, prevalence, and severity [

14].

Cook County, of which 85% is Chicago, has been ranked among the worst 10% of counties in the United States air quality indicators [

15]. Therefore, Chicago provides a unique opportunity to examine the potential impact of air pollutants, as well as other urban risk factors, on the prevalence of UFs. Since 2013, a predominantly Black population on Chicago’s South Side has been enrolled into the Chicago Multiethnic Prevention and Surveillance Study (COMPASS) with a goal of mitigating health disparities [

16]. To this end, extensive data has been collected to understand individual, neighborhood and environmental factors relevant for disease prevention, disparity mitigation, and improved health outcomes. In this study we analyzed data from a sample of participants enrolled in this existing longitudinal cohort study to assess the relationship between individual-level, neighborhood, and environmental variables and UF prevalence.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study analyzed the baseline data of a sample of participants from COMPASS. Data included in this study were collected from July 2019 - May 2020. A more detailed description of COMPASS study design can be found elsewhere [

16].

2.2. Study Population

The sample analyzed in this study was obtained from COMPASS. Established in 2013, COMPASS is a longitudinal prospective cohort study that includes 8,000 participants in the City of Chicago. Its purpose is to assess the influence of factors, such as neighborhood, environment, exposure to air pollutants, socioeconomic status, healthcare access, lifestyle, behavior, and genetics, on the health of Chicagoans. COMPASS enrolls residents of the greater Chicago area who are at least 18 years of age, and not incarcerated at the time of enrollment. The survey was designed by co-authors Drs. Aschebrook-Kilfoy and Ahsan. Most survey items are harmonized with existing NIH/NCI surveys.

To investigate the possible correlation between these above-mentioned factors and UF diagnosis, we analyzed data of COMPASS participants who responded to the question, "Has a doctor or healthcare professional ever diagnosed you with uterine fibroids?" Based on their responses, we categorized participants into two groups: those who had received a UF diagnosis (yes) and those who had not (no).

2.3. Individual-Level Variables

Demographic factors such as age, race, and ethnicity, as well as lifestyle and behavioral factors, including activity levels, alcohol intake, and smoking, were reported through the questionnaire. Additionally, access to healthcare; neighborhood factors, such as crime and safety; socioeconomic status, including employment status and income status; and reproductive history, including pregnancy and hysterectomy were reported through the questionnaire. All participants in the sample listed female as their gender. We categorized participants as either active or inactive based on their reported participation in at least one of the 15 physical activities listed in the questionnaire (ranging from household chores to vigorous workouts). Participants were classified as "smokers" if they reported smoking cigarettes, cigars, marijuana, or vaping nicotine and/or tobacco, daily or weekly. Participants were classified as “alcohol consumers” if they reported regular alcohol consumption and the intake of multiple alcoholic beverages within the last 12 months. Employment status was divided into four categories: employed, unemployed, retired, or unknown. Income status was divided into three categories: low income ($34,999 or less), middle income ($35,000-$89,999), or high income ($90,000 or above).

Access to healthcare was assessed using two variables: "access to care" and "quality of care." The metric for access to care was determined by combining participants' responses to questions on where they go to for health care (i.e., urgent care, emergency room, clinic visit etc.), their perception of the number of doctors in their community, and whether they had ever been turned away by a doctor for financial or insurance reasons. Quality of care was evaluated based on participants' satisfaction with the care they received in the last 12 months and their agreement with statements about their doctors' medical knowledge and amount of time spent with patients.

2.4. Neighborhood Variables

To investigate possible impacts of participants’ perception of neighborhood crime and violence on physical activity levels, participants' responses to questions regarding their choice to forego exercise due to concerns about crime and violence, as well as the impact of these concerns on their daily life, were assessed. Contextual neighborhood variables were analyzed using Chicago Health Atlas (CHA) data for each Chicago community area between 2015 and 2019 [

17]. Chicago has distinct community areas (aka neighborhoods). COMPASS links survey data to community areas and CHA data is merged onto COMPASS data on the shared community area level. Six neighborhood variables were included: the hardship index (composite score reflecting hardship in the community), the neighborhood safety rate (% of adults who report that they feel safe in their neighborhood “all the time” or “most of the time”), low food access (% of residents who must travel further than ½ mile to the nearest supermarket in urban areas or 10 miles in rural areas), traffic intensity (proximity to vehicle traffic), the social vulnerability index (percentile relative vulnerability based on social factors), and the rate of received needed care (% of adults who report that it is “usually” or “always” easy to get care with their health plan).

2.5. Environmental Variables

Ambient exposure data, including PM2.5, ozone, diesel particulate matter (DSLPM), and proximity to traffic (PTRAF) was extracted from COMPASS, which obtains air quality data by geocoding participant-supplied addresses and linking them to one of 77 Chicago community areas and their census tract or block. These ambient exposure levels are derived from the 2019 Environmental Justice Screening (EJSCREEN) air quality data and merged with the COMPASS data set using the EJSCREEN ID variable at the census FIPS code block group level.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the investigated variables from the COMPASS dataset and the selected contextual neighborhood variables retrieved from the Chicago Health Atlas (CHA) for each Chicago community were linked to individual participants. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)] was reported for continuous variables based on data normal distribution, and frequencies and percentages were presented for categorical variables. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used to examine whether the variables were normally distributed. Differences in subject characteristics between groups were analyzed by two-sample t or Mann-Whitney tests, depending on the distributions for continuous variables, and by Pearson's chi-squared or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to investigate trends in age, race, access to quality care, behavioral lifestyle, contextual neighborhood factors, socioeconomic status, and ambient exposures related to UF, illustrating the odds ratio (OR) value with 95% confidence interval (CI). In addition, potential risk factors for UFs were identified in the multivariable logistic regression model. Of note, a multilevel model was not utilized to analyze the contextual neighborhood variables because the available data had no hierarchical or clustered structure. We used Spearman's rank correlation coefficient with Bonferroni correction to assess the contextual neighborhood correlations because the contextual neighborhood data were not approximately normal distributions. Mixed positive and negative correlations did not satisfy the critical assumption of unidirectionality needed for the weighted quantile sum (WQS) analysis for the overall mixture effect of neighborhood characteristics, which was performed in a similar study by a co-author, Dr. Aschebrook-Kilfoy [

18,

19]. Lastly, multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess the impact of contextual neighborhood variables on UF diagnosis adjusted by race and household income status. Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were conducted in the Stata/SE software 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

A total of 602 participants aged 35-76 years (mean (SD): 50.3 ± 12.3) met criteria for this study, and 21% self-reported a UF diagnosis. See

Table 1 for a summary of participants’ demographics, lifestyle, and reproductive history. Univariate analysis of each variable is reported in this section unless otherwise indicated.

3.1. Individual-Level Variables

3.1.1. Demographic Factors

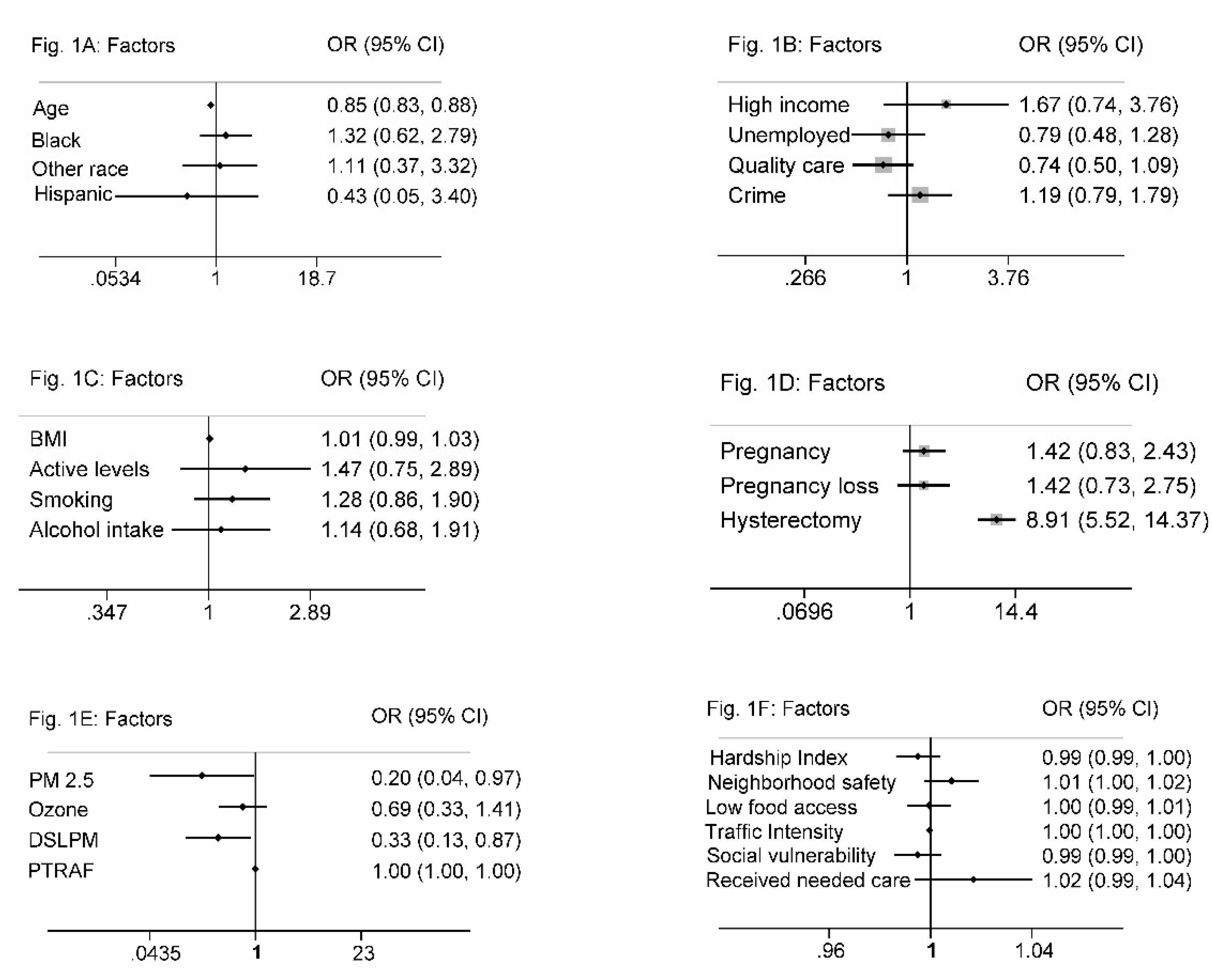

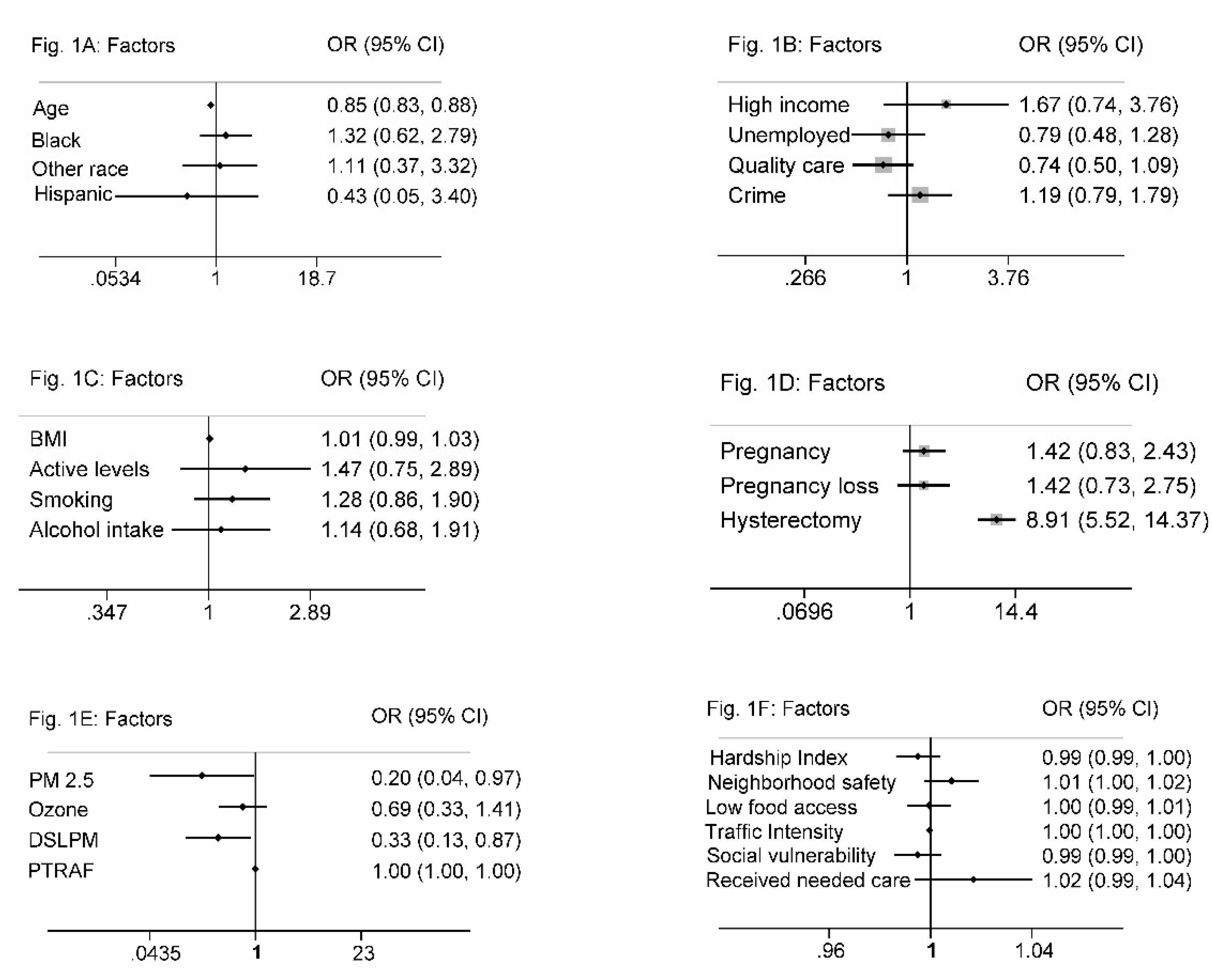

The average age of participants with a UF diagnosis was 37 years. In our sample, 85% identified as Black, 9% as White, and 6% as other. The odds of a UF diagnosis decreased with age (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.83 to 0.88). Black participants had higher odds of a UF diagnosis when compared to White participants (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.62 to 2.79) or other (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.37 to 3.32). 90.7% of the sample were non-Hispanic, 7.6% were unknown, and 1.7% were Hispanic. Participants of Hispanic ethnicity had lower odds of a UF diagnosis (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.05 to 3.40). The mean age of participants with a UF diagnosis was lower in Black (36.5 years) compared to White, (41.6 years) or participants of other races (41 years), p-value of 0.330. (

Figure 1A).

3.1.2. Socioeconomic Factors

Seventy percent of the participants were in the low-income bracket. Those in higher income brackets had increased odds of a UF diagnosis. Unemployed participants had decreased odds of a UF diagnosis (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.48 to 1.28), and 39% of the sample participants reported having no access to quality healthcare. Patients with access to quality care were approximately 26% less likely to receive a UF diagnosis (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.50 to 1.09). 42% of the sample participants reported having an insufficient number of doctors in their community. Participants who reported having enough doctors in their community had lower odds of a UF diagnosis (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.61 to 1.52). 42% of participants reported concerns about crime and neighborhood violence. Participants who had daily concerns about crime trended towards higher odds of receiving a UF diagnosis (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.79) compared to those who did not have these concerns. (

Figure 1B)

3.1.3. Lifestyle and Behavioral Factors

Fifty-two percent of participants were categorized as obese (BMI > 30), 24% as overweight (BMI 25 to < 30), 20% as healthy weight (BMI 18.5 to < 25), and 4% as underweight (BMI < 18.5). We observed a positive trend between BMI and a UF diagnosis; obese participants had 1.5 times higher odds of a UF diagnosis compared to participants with a normal BMI (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 0.87 to 2.56). UF diagnoses were less likely in participants who reported daily exercise (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.48). Within our sample, 88.5% of the participants reported having an active lifestyle, and these participants were more likely to have a UF diagnosis (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 0.75 to 2.89). Fifty-two percent of the sample participants were smokers, and they were 1.28 times more likely to have a UF diagnosis (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.90). Additionally, 44% of the sample participants reported childhood secondhand smoke exposure, which was associated with increased odds of a UF diagnosis (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 0.84 to 2.52). Of the sample participants, 17% reported regular alcohol consumption (every day or every week), 40% denied regular alcohol use, and 42% reported unknown alcohol usage. Those who reported regular alcohol use were 1.14 times more likely to have a UF diagnosis (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.68 to 1.91). (

Figure 1C)

3.1.4. Reproductive History

A history of pregnancy was reported by 81% of participants. These participants had higher odds of a UF diagnosis (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.83 to 2.43). The odds of a UF diagnosis were also higher in participants who experienced pregnancy loss (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.73 to 2.75). Abortions were slightly more common among participants with a UF diagnosis (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.43 to 1.30). Sixteen percent of participants reported having a hysterectomy while 84% denied having undergone the procedure. The odds of a UF diagnosis were 8.9 times higher in participants who had undergone a hysterectomy (OR, 8.91; 95% CI, 5.52 to 14.37). (

Figure 1D)

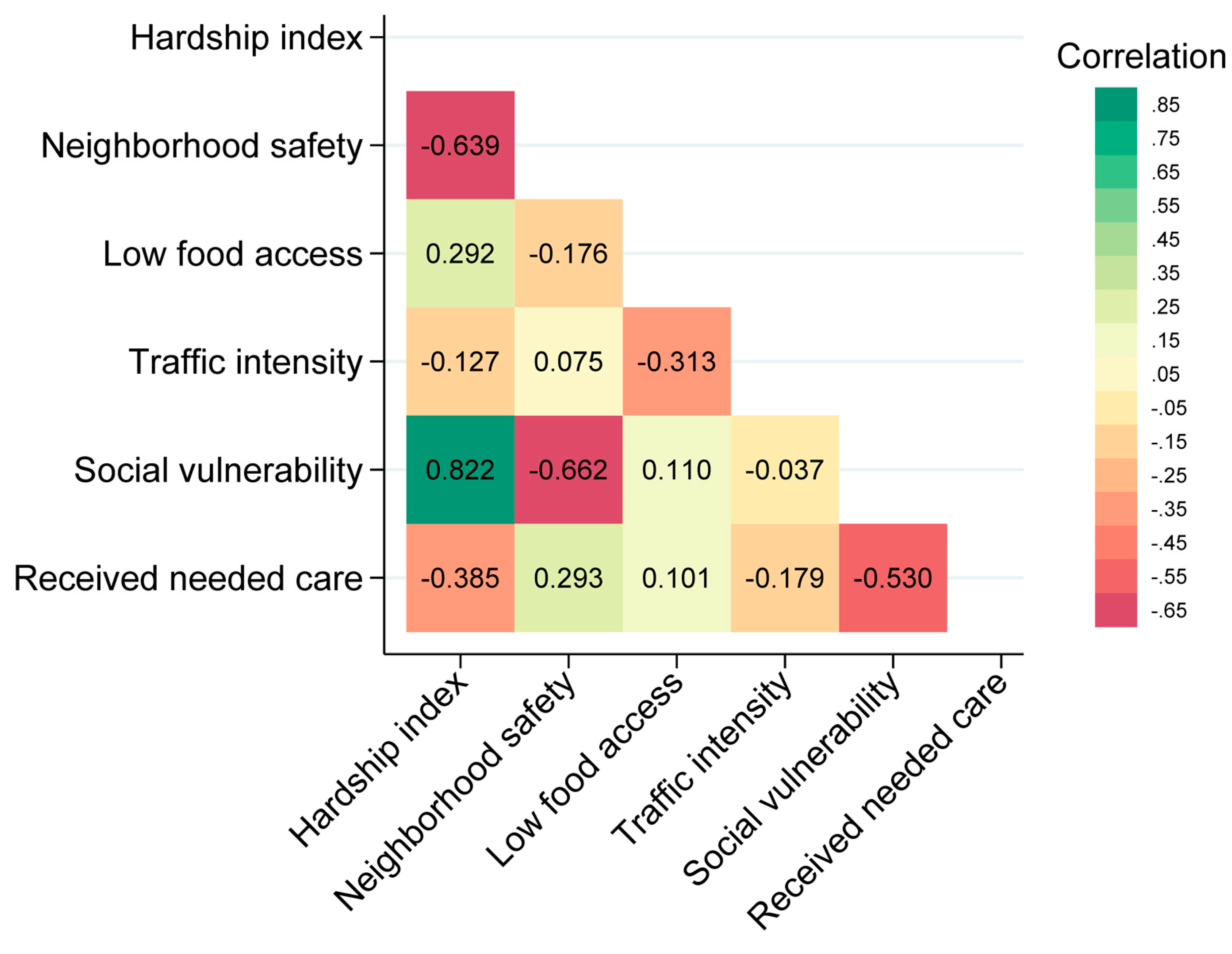

3.2. Neighborhood Variables

Except for traffic intensity, neighborhood contextual characteristics were similar across groups (

Table 2). Each selected neighborhood characteristic showed no significant association with a UF diagnosis (

Figure 1F). Spearman’s correlation of the six neighborhood characteristics showed moderate correlations between several. The Spearman's correlation coefficient indicated a value of 0.82 between the hardship index and social vulnerability and 0.63 between the hardship index and neighborhood safety (

Figure 2). When stratified by individual-level variables, race, and household income status, the six neighborhood characteristics did not have a statistically significant impact on the odds of a UF diagnosis. When adjusted for age, traffic intensity was slightly protective against a UF diagnosis.

3.3. Environmental Variables

PM2.5 was associated with decreased odds of a UF diagnosis (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.97). DSLPM exposure decreased the odds of UF diagnosis (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.13 to 0.87). Ozone levels did not follow a normal distribution and median concentration exposures were similar in both groups at 45.409 μg/m3. Additionally, ozone exposure decreased the odds of a UF diagnosis, although the effect was not statistically significant (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.33 to 1.41). Average PTRAF exposure was 9.825 μg/m3 and it did not significantly impact the odds of a UF diagnosis in our sample. (

Figure 1E). Of note, other multivariable analyses performed did not meet the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test.

4. Discussion

In recent years, considerable attention has been given to understanding the role of social, economic, and environmental factors on health inequity [

20]. This study explores UF prevalence among predominantly Black urban residents in Chicago, considering individual, neighborhood, and environmental factors. Chicago's unique features—socioeconomic profile, demographic composition, high traffic, and industrial presence, leading to poor air quality—make it an ideal location for assessing UF prevalence [

15]. However, these features affect the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, the small sample size, relatively narrow exposure distribution, and oversampling of non-Hispanic Blacks, who are disproportionately impacted by UFs, may explain the lack of statistically significant findings.

In this study, 85% of participants were non-Hispanic Blacks. Black participants had a higher likelihood of a UF diagnosis, and we observed a positive correlation between a UF diagnosis and lifestyle and demographic factors such as regular alcohol use, secondhand smoke exposure, elevated BMI, and infrequent exercise. These findings are consistent with well-established data [

1,

3,

5,

9]. The association we found between an active lifestyle and higher odds of a UF diagnosis was unexpected and may be attributable to physical activity overestimation bias, since our classification process was based on participants’ self-report of engagement in activities [

21]. Forty-two percent of participants reported concerns about crime and violence, which impacted their ability to engage in outdoor physical activity and affected their daily lives. Participants with these concerns had higher odds of a UF diagnosis. Despite the lack of statistical significance, which could be attributed to an overall small sample size, this correlation is as expected because crime and violence are a significant source of chronic stress, which can lead to allostatic load and a subsequent pro-inflammatory state [

22]. Chronic inflammation has been implicated in the development of UFs and may be a critical contributing factor to the racial disparity observed in UF diagnoses. The increased odds of a UF diagnosis in participants reporting a history of pregnancy loss and hysterectomy are consistent with published data and underscore the substantial morbidity associated with UFs, as well as their negative impact on quality of life [

1,

23]. While research has suggested that pregnancy protects against UF occurrence [

24], our study found that participants who had been pregnant before had higher odds of a UF diagnosis. This finding could be due to the common occurrence of UF diagnoses during pregnancy.

Neighborhood characteristics, independently and stratified by individual level variables (race, and household income), did not significantly influence UF diagnoses. This was an unexpected finding, and we suspect is due to an overall low sample size i.e., Type II error [

25]. Furthermore, no statistically significant correlation was found between ozone or PTRAF exposure and UF diagnoses, whereas DSLPM and PM2.5 showed statistically significant negative correlations with UF diagnosis. These findings were not as expected because previous studies have explored the association between air pollutants and UFs, with some reporting a modest increased risk of UF with ozone and PM2.5 exposure [

12,

13,

14]. Our findings may differ from prior studies, due to overall lower levels and narrower ranges of ozone (44-46 μg/m3 vs. 50.74-71.04 μg/m3 in Black Woman’s Health Study) and average PM2.5 (9.82 μg/m3 vs. 13.6 μg/m3 in Black Woman's Health Study and 15.3 μg/m3 in The Nurses' Health Study II). Although our findings do not invalidate previous data, they suggest a possible threshold exposure level where UF risk increases, and larger variations in exposure levels may allow differences to be observed, while smaller variations reduce the ability to detect such differences.

4.1. Strengths & Limitations

This study has several strengths. First, the disadvantaged group most impacted by UF is adequately represented in our study sample. Second, our data source, COMPASS, provides access to specific neighborhood characteristics using participant supplied addresses instead of proxy variables. Third, this paper investigates an important and understudied issue of the social and environmental causes of health inequity in UF prevalence. There are several limitations of this study. First, despite access to a large cohort, we performed a cross sectional analysis of a relatively small sample of 602 participants who completed the survey module assessing UF diagnosis. The analyzed sample was not nationally or geographically representative and although over representation of disadvantaged groups is a strength, it limits the generalizability of our study findings. Second, the age and report of UF diagnosis is not validated by medical data. This, along with other findings, may be influenced by questionnaire and recall bias [

26]. To mitigate these limitations for future studies using COMPASS, we will request that a UF diagnosis be included in all surveys, as well as questions addressing age at diagnosis and verification of an image-confirmed diagnosis. Lastly, the lack of a temporal association between air pollutant data collection and the date of UF diagnosis, due to the nature of survey response collection, limits the interpretation of our findings on the impact of air pollution exposure on a UF diagnosis. Future studies with larger sample sizes, wider exposure distributions, inclusion of medical record data, and more comprehensive data collection methods will contribute to a deeper understanding of the factors influencing UF diagnoses.

4.2. Further Research

To reflect the association more accurately between exposures and disease diagnosis, studies evaluating the impact of socioeconomic, lifestyle, and environmental factors on UFs should capture both the age at diagnosis and the duration of environmental exposures leading to or at the time of diagnosis. Additionally, participants from cohorts specifically designed to investigate health conditions, such as UFs, should be sampled for analysis. Alternatively, existing cohorts, such as COMPASS, could be modified accordingly, to avoid limited and inaccurate information about the condition in question. Lastly, similar studies using population-based cohorts could enhance heterogeneity and variability within the cohort, thereby improving the generalizability of the study results.

5. Conclusions

The impact of structural and environmental factors on UF development is a growing area of research interest. Our investigation of this relationship in a predominantly Black Chicago-Based cohort which includes individuals residing in historically disenfranchised communities of South Chicago did not reveal significant associations between these structural drivers and UF prevalence. However, our study provides foundational insights into the cohort that we queried and identifies an opportunity to leverage an existing longitudinal cohort study by expanding its variables to include gynecologic specific data that would improve the robustness of future analysis. Future analysis with more robust data may allow us to determine if there is a significant association between structural and environmental variables and UF prevalence. Identifying this relationship, if it exists, would provide a justifiable platform to pursue policy changes.

Authors Contribution

OSM-L recognized the educational value of this study, assembled the research team, and coordinated the execution of the study. The COMPASS study protocol was designed by HA. KO directs the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center (UCCC) which provides funding support for COMPASS. BA-K oversaw field operations and MGK oversaw the biosample processing and biobanking. HA BA-K oversaw engagement. NR performed the data quality control and the statistical analysis for the COMPASS study and abstracted the relevant data for the fibroid prevalence study. Data cleaning of the abstracted COMAPSS study data was performed by SN and TT. The fibroid prevalence study protocol was designed by OSM-L, SN and TT. Data analysis for the fibroid prevalence study was performed by CL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SN, TT, CL and OSML. All authors participated in the study design, revised the article and approved the final version.

Funding

Funding for COMPASS came from the Institute for Population and Precision Health at the University of Chicago and the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center. Additionally, environmental linkage was funded by NIEHS Grant #P30 ES027792.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. COMPASS will continue to collect a rich set of data on multiple exposure domains and health outcomes. For more information, refer to the website: compass.uchicago.edu. Researchers interested in collaboration are invited to propose research questions based on the data available within COMPASS or to submit a request for additional data collection. Requests can be submitted electronically on the COMPASS website and will be reviewed by the COMPASS scientific board. The COMPASS study team is particularly interested in collaborations that will enhance research methods for this type of work, assess the impact of environmental exposure, highlight exposures of key significance in urban communities and address health issues of concern in Chicago and other urban centers.

Acknowledgments

We thank the dedicated COMPASS field staff and community partners for their support of this work.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose

Ethics Approval

All study procedures and materials were reviewed and approved by the University of Chicago

Biological Sciences Division Institutional Review Board Committee A (approval IRB12-1660)

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or

reporting, or dissemination plans of this research

Consent to Participate

consent was not required for this study

Consent to Publish

Consent to publish was not required for this study.

References

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine Fibroids: Burden and Unmet Medical Need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35(6):473-480. [CrossRef]

- Sutton MY, Anachebe NF, Lee R, Skanes H. Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive health services and outcomes, 2020. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2021;137(2):225.

- Wise, L. A., Palmer, J. R., Cozier, Y. C., Hunt, M. O., Stewart, E. A., & Rosenberg, L. (2007). Perceived racial discrimination and risk of uterine leiomyomata. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 18(6), 747–757. [CrossRef]

- Igboeli, P., Walker, W., McHugh, A., Sultan, A., & Al-Hendy, A. (2019). Burden of Uterine Fibroids: An African Perspective, A Call for Action and Opportunity for Intervention. Current opinion in gynecology and obstetrics, 2(1), 287–294. [CrossRef]

- Pavone, D., Clemenza, S., Sorbi, F., Fambrini, M., & Petraglia, F. (2018). Epidemiology and risk factors of uterine fibroids. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 46, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Ciebiera M, Bariani MV, Ali M, Elkafas H, Boyer TG et al. Comprehensive review of uterine fibroids: developmental origin, pathogenesis, and treatment. Endocrine reviews. 2022;43(4):678-719.

- Millien, C., Manzi, A., Katz, A. M., Gilbert, H., Smith Fawzi, M. C., Farmer, P. E., & Mukherjee, J. (2021). Assessing burden, risk factors, and perceived impact of uterine fibroids on women's lives in rural Haiti: implications for advancing a health equity agenda, a mixed methods study. International journal for equity in health, 20(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Morello-Frosch R, Lopez R. The riskscape and the color line: examining the role of segregation in environmental health disparities. Environmental research. 2006 ;102(2):181-96.

- Tinelli A, Vinciguerra M, Malvasi A, Andjić M, Babović I, Sparić R. Uterine Fibroids and Diet. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1066. Published 2021 Jan 25. [CrossRef]

- Tung, E. L., Johnson, T. A., O’Neal, Y., Steenes, A. M., Caraballo, G., & Peek, M. E. (2018). Experiences of community violence among adults with chronic conditions: Qualitative findings from Chicago. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(11), 1913–1920. [CrossRef]

- Kalra GL, Watson KE. Health Consequences of Segregation and Disenfranchisement. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(3):e024772. [CrossRef]

- Lin CY, Wang CM, Chen ML, Hwang BF. The effects of exposure to air pollution on the development of uterine fibroids, International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, Volume 222, Issue 3, 2019, Pages 549-555, ISSN 1438-4639. [CrossRef]

- Wesselink AK, Rosenberg L, Wise LA, Jerrett M, Coogan PF. A prospective cohort study of ambient air pollution exposure and risk of uterine leiomyomata, Human Reproduction, Volume 36, Issue 8, August 2021, Pages 2321–2330.

- Mahalingaiah S, Hart J, Laden F, Terry K, Boynton-Jarrett R, Aschengrau A, Missmer S. Air Pollution and Risk of Uterine Leiomyomata, Epidemiology: September 2014 - Volume 25 - Issue 5 - p 682-688.

- King K. E. (2015). Chicago Residents' Perceptions of Air Quality: Objective Pollution, the Built Environment, and Neighborhood Stigma Theory. Population and environment, 37(1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Kibriya MG, Jasmine F, et al. Cohort profile: the Chicago Multiethnic Prevention and Surveillance Study (COMPASS). BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e038481.

- Chicago Health Atlas. Available at https://chicagohealthatlas.org/. Accessed May 16, 2023.

- Carrico C, Gennings C, Wheeler DC, et al. Characterization of weighted quantile sum regression for highly correlated data in a risk analysis setting. J Agric Biol Environ Stat. 2015; 20(1):100-120.

- Luo J, Kibriya MG, Shah S, et al. The Impact of Neighborhood Disadvantage on Asthma Prevalence in a Predominantly African-American, Chicago-Based Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2023;192(4):549-559. [CrossRef]

- Islam MM. Social Determinants of Health and Related Inequalities: Confusion and Implications. Front Public Health. 2019;7:11. Published 2019 Feb 8. [CrossRef]

- Watkinson, C., van Sluijs, E.M., Sutton, S. et al. Overestimation of physical activity level is associated with lower BMI: a cross-sectional analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 7, 68 (2010). [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. (1998). Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338:171-179.

- Weiss, G., Noorhasan, D., Schott, L. L., Powell, L., Randolph, J. F., Jr, & Johnston, J. M. (2009). Racial differences in women who have a hysterectomy for benign conditions. Women's health issues: official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health, 19(3), 202–210. [CrossRef]

- Laughlin SK, Herring AH, Savitz DA, Olshan AF, Fielding JR, Hartmann KE, Baird DD. Pregnancy-related fibroid reduction, Fertility and Sterility, Volume 94, Issue 6, 2010, Pages 2421-2423, ISSN 0015-0282. [CrossRef]

- MO Columb, FRCA FFICM, MS Atkinson, FRCA FFICM, Statistical analysis: sample size and power estimations, BJA Education, Volume 16, Issue 5, May 2016, Pages 159–161. [CrossRef]

- Schmier, J. K., & Halpern, M. T. (2004). Patient recall and recall bias of Health State and health status. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 4(2), 159–163. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A. Odds of UF diagnosis by Demographic factors: Age, Race (Black), ethnicity. Odds ratio and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were utilized for an Interquartile range where continuous predictors Age compared quartile 3 with quartile 1. Categorical predictors Race, Daily Exercise, and Active lifestyle utilized simple odds and compared them to a reference group (White, normal BMI, No exercise, not active lifestyle). Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of developing uterine fibroid. Age: continuous variable. Race: White, Black, and Other. Figure 1B. Odds of UF diagnosis by Income/Employment Status, Access to Quality Care, and Crime. Categorical predictors Income status, Employment status, access to quality care, and crime utilized simple odds and compared them to a reference group (low income, employed, no quality care, not enough doctors, and no crime). Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of developing uterine fibroid. Conversely, an odds ratio of less than 1 represents a protective effect. Figure 1C. Odds of UF diagnosis by lifestyle & behavioral: BMI, activity levels, alcohol intake, smoking. Odds ratio and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were utilized for an Interquartile range where continuous predictor BMI compared quartile 3 with quartile 1. Categorical predictors smoking status, secondhand smoking exposure, and alcohol consumption utilized simple odds and compared them to a reference group (normal BMI, No exercise, not active lifestyle, no alcohol intake, and no smoking). Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of uterine fibroid diagnosis. BMI: Underweight, Normal, Overweight, Obese. Daily exercise: No exercise, daily exercise. Active lifestyle: Inactive lifestyle, active lifestyle. Figure 1D. Odds of UF diagnosis by pregnancy & hysterectomy history. Categorical predictors’ previous pregnancy status, Pregnancy loss experience, and Hysterectomy utilized simple odds and comparing them to a reference group of zero or not experienced. Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased odd of uterine fibroid diagnosis. Figure 1E. Odds of UF diagnosis by Ambient Exposure Ranges. Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of developing uterine fibroid. Conversely, an odds ratio of less than 1 represents a protective effect. Figure 1F. Odds of UF diagnosis by Neighborhood contextual variables. Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of developing uterine fibroid. Conversely, an odds ratio of less than 1 represents a protective effect.

Figure 1.

A. Odds of UF diagnosis by Demographic factors: Age, Race (Black), ethnicity. Odds ratio and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were utilized for an Interquartile range where continuous predictors Age compared quartile 3 with quartile 1. Categorical predictors Race, Daily Exercise, and Active lifestyle utilized simple odds and compared them to a reference group (White, normal BMI, No exercise, not active lifestyle). Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of developing uterine fibroid. Age: continuous variable. Race: White, Black, and Other. Figure 1B. Odds of UF diagnosis by Income/Employment Status, Access to Quality Care, and Crime. Categorical predictors Income status, Employment status, access to quality care, and crime utilized simple odds and compared them to a reference group (low income, employed, no quality care, not enough doctors, and no crime). Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of developing uterine fibroid. Conversely, an odds ratio of less than 1 represents a protective effect. Figure 1C. Odds of UF diagnosis by lifestyle & behavioral: BMI, activity levels, alcohol intake, smoking. Odds ratio and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were utilized for an Interquartile range where continuous predictor BMI compared quartile 3 with quartile 1. Categorical predictors smoking status, secondhand smoking exposure, and alcohol consumption utilized simple odds and compared them to a reference group (normal BMI, No exercise, not active lifestyle, no alcohol intake, and no smoking). Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of uterine fibroid diagnosis. BMI: Underweight, Normal, Overweight, Obese. Daily exercise: No exercise, daily exercise. Active lifestyle: Inactive lifestyle, active lifestyle. Figure 1D. Odds of UF diagnosis by pregnancy & hysterectomy history. Categorical predictors’ previous pregnancy status, Pregnancy loss experience, and Hysterectomy utilized simple odds and comparing them to a reference group of zero or not experienced. Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased odd of uterine fibroid diagnosis. Figure 1E. Odds of UF diagnosis by Ambient Exposure Ranges. Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of developing uterine fibroid. Conversely, an odds ratio of less than 1 represents a protective effect. Figure 1F. Odds of UF diagnosis by Neighborhood contextual variables. Odd ratios above 1 indicate an increased risk of developing uterine fibroid. Conversely, an odds ratio of less than 1 represents a protective effect.

Figure 2.

Spearman correlation of Neighborhood contextual variables. Neighborhood contextual factors are categorized into interquartile ranges. Median hardship index (score), neighborhood safety rate (% of adults), low food access (% of residents), traffic intensity (distance-weighted vehicles), social vulnerability index, received needed care rate (% of adults).

Figure 2.

Spearman correlation of Neighborhood contextual variables. Neighborhood contextual factors are categorized into interquartile ranges. Median hardship index (score), neighborhood safety rate (% of adults), low food access (% of residents), traffic intensity (distance-weighted vehicles), social vulnerability index, received needed care rate (% of adults).

Table 1.

Summary of Participants’ demographics, lifestyle, and reproductive history.

Table 1.

Summary of Participants’ demographics, lifestyle, and reproductive history.

| |

Entire Sample

(N = 602) |

Fibroid Diagnosis

(N = 127) |

No Fibroid Diagnosis

(N = 475) |

P-value |

|

Age (year), mean ± SD |

50.3 ± 12.3 |

37.1 ± 10.5 |

53.8 ± 10.1 |

< 0.001 |

|

BMI, mean ± SD |

31.4 ± 9.0 |

32.2 ± 7.8 |

31.2 ± 9.3 |

0.265 |

|

Race, n (%) |

| Black |

513 (85.2) |

111 (87.4) |

402 (84.6) |

0.792 |

| White |

52 (8.6) |

9 (7.1) |

43 (9.1) |

| Other |

37 (6.2) |

7 (5.5) |

30 (6.3) |

|

Ethnicity, n (%) |

|

| Non-Hispanic |

546 (90.7) |

113 (89.0) |

433 (91.2) |

0.391 |

| Hispanic |

10 (1.7) |

1 (0.8) |

9 (1.9) |

| Unknown |

46 (7.6) |

13 (10.2) |

33 (7.0) |

|

Socioeconomic Status, n (%) |

| Employment Status

|

| Employment |

127 (21.1) |

30 (23.6) |

97 (20.4) |

0.360 |

| Unemployed |

368 (61.1) |

72 (56.7) |

296 (62.3) |

| Retired |

65 (10.8) |

18 (14.2) |

47 (9.9) |

| Unknown |

42 (7.0) |

7 (5.5) |

35 (7.4) |

| Income Status a

|

| Low income |

422 (70.1) |

83 (65.4) |

339 (71.4) |

0.337 |

| Middle income |

44 (7.3) |

8 (6.3) |

36 (7.6) |

| High Income |

31 (5.2) |

9 (7.1) |

22 (4.6) |

| Unknown |

105 (17.4) |

27 (21.3) |

78 (16.4) |

|

Behavioral Lifestyle, n (%) |

| Alcohol/Smoking Status |

| Smoking Status |

| Smoker |

312 (51.8) |

72 (56.7) |

240 (50.5) |

0.231 |

| Non-Smoker |

290 (48.2) |

55 (43.3) |

235 (49.5) |

| Alcohol Consumption |

| Consumer |

105 (17.4) |

29 (22.8) |

76 (16.0) |

0.623 |

| Non-Consumer |

243 (40.4) |

61 (48.0) |

182 (38.3) |

| Unknown |

254 (42.2) |

37 (29.1) |

217 (46.7) |

|

Reproductive History, n (%) |

| Pregnancy outcome |

| Live birth |

375 (62.3) |

79 (62.2) |

296 (62.3) |

0.385 |

| Pregnancy loss |

51 (8.47) |

14 (11) |

37 (7.8) |

| Abortion |

62 (10.3) |

15 (11.8) |

47 (9.9) |

| Not reported |

114 (18.9) |

19 (15) |

95 (20) |

| Hysterectomy |

97 (16.4) |

57 (45.6) |

40 (8.6) |

< 0.001 |

Table 2.

Summary of Neighborhood Characteristics.

Table 2.

Summary of Neighborhood Characteristics.

|

Neighborhood Characteristic, median (interquartile range) |

| |

Entire Sample

(N = 602) |

Fibroid Diagnosis

(N = 127) |

No Fibroid Diagnosis

(N = 475) |

P-value |

| Hardship Index |

83.1 (75.3-89.3) |

83.1 (57.3-86.9) |

83.1 (75.3-89.8) |

0.338 |

| Neighborhood safety |

47.1 (33.6-58.2) |

47.5 (36.5-59.2) |

46.3 (33.6-58.2) |

0.130 |

| Low food access |

36.9 (22.3-63.5) |

36.9 (22.3-63.5) |

36.9 (22.3-63.5) |

0.768 |

| Traffic Intensity |

615.3 (411.5-1630.2) |

563.1 (411.5-1013.0) |

619.2 (411.5-1630.2) |

0.031 |

| Social vulnerability |

81.5 (72.7-83.5) |

81.5 (69.4-82.6) |

81.5 (74.0-83.5) |

0.284 |

| Received needed care |

77.2 (72.7-86.5) |

79.3 (74.6-87.6) |

77.2 (72.7-86.2) |

0.143 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).