Introduction

A plethora of research has investigated the performance and functioning of teachers amid the COVID-19 crisis globally and within the specific context of Israel (Donitsa-Schmidt & Ramot, 2022: Billett et al, 2023). However, a research gap persists regarding teachers’ sense of self-efficacy in the face of the intricate situations arising from the pandemic and the contributing factors influencing this sense (Pressley & Ha, 2021). This current study aims to address this gap by adopting a research approach derived from retrospective observation (Aktaş, 2018; Davis & Waite, 2003). This approach captures teachers’ experiences in the present by retrospectively observing their pre-service training—a representation embedded in their current consciousness. Consequently, we explore the significance of prior teacher training and its implications for evaluating their self-efficacy as teachers during the peak of the pandemic. The study endeavors to construct a comprehensive framework illustrating a transfer from teachers’ inner world, their perceptions of their prior training, as a reflexive representation of their intrapersonal and professional consciousness. This approach facilitates an expanded understanding of the importance of optimal pre-service training and its enduring impact on teachers’ self-efficacy and professional resilience during a crisis. The retrospective observation acts as a mediator, portraying a layered depiction of the evolving sense of self-efficacy tested in times of crisis.

Literature Review:

In recent years, scholarly interest in teachers’ self-efficacy has grown, recognized for its significance in fostering efficiency, satisfaction, reducing burnout rates, and preventing dropout from the teaching profession (Klassen & Tze, 2014). Contemporary studies underscore the positive impact of enhancing teachers’ expertise, professional development, collaborative efforts, and teaching quality on their sense of efficacy (Narayanan & Ordynans, 2022).

Teacher Education in Israel:

The Israeli teacher education model spans four years across 21 colleges and 9 universities, culminating in a B.Ed degree and teaching certificate for pre-service teachers (PSTs). This holistic program integrates education and discipline-specific courses with practical experiences, embodying a ’learning by doing’ ethos (Dror, 2016; Auther et al., 2020). Evaluations of teacher education extend to teacher quality, teaching efficacy, and impact on student achievements (Arnon et al., 2015). Teacher education institutions emphasize the pivotal role of teacher educators, lecturers, and counselors as PST role models, shaping PSTs’ professional identities (Izadinia, 2014).

Recent findings reveal positive correlations between graduates of teaching programs, collaborative models, high self-efficacy, and readiness for teaching (Makdosi, 2018; Aran & Zaretsky, 2017). Notably, heightened self-efficacy predicts novice teachers’ commitment beyond three years in the profession (Author et al., 2023). Despite this, approximately 45% of novice teachers in Israel leave the education system within five years (data presentation to presidents of colleges of education and teaching, 2021), underscoring the practical importance of studying teachers’ self-efficacy and its influencing factors.

Methodology:

This study employs a quantitative research method through a self-report questionnaire, focusing on retrospective reflections on past training. This approach allows an understanding of past processes influencing the present, relying on participants’ memories and experiences. Triangulation of information sources, literature review, and a validated questionnaire, reviewed by content experts, enhance the study’s robustness and reliability.

Distribution and data collection

The questionnaire was distributed in a single phase to a convenience sample of some 800 teachers who are graduates of a northern Israeli college of education and had completed their studies in the previous decade. The questions were preceded by an explanation of the research aims and respondents were promised strict anonymity. The questionnaire was distributed via the college email system at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and remained available for three months, until March 2021. This was a period when teachers were required to excel in light of the long lockdowns Data processing included accepted descriptive statistical tests to obtain as accurate a picture as possible with SPSS software (Mean, SD, and two-variable Pearson Moment) and t-tests.

Research questions

Is there any correlation between past training and the sense of self-efficacy in the present?

How do teachers rate their self-efficacy during the studied period of the pandemic?

What factors influence how teachers rate their self-efficacy? Which factors’ influences were not proven?

Research population

Participants were 165 teachers from northern Israel working in the education system who had completed their teacher education in the previous 10 years. Of these, 115 (69.7%) were women and 50 (30.3%) were men. Age rage was 25-60 (M=37.96; SD=8.04), with seniority ranging from 0-31 years (M=7.98; SD=6.59). Most participants were married (81.2%), Jewish (72%) and nearly all academics (98.8%).

Table 1 below presents the distribution of the participants according to demographics:

Table 2.1 presents the teachers’ responses for the evaluation of their preservice training lecturers at the college.

Table 2.1.

Characteristics, Mean, SD, & validity of statements re lecturer perseptions (N=165).

Table 2.1.

Characteristics, Mean, SD, & validity of statements re lecturer perseptions (N=165).

| Measure/Statement |

# of statements |

Min |

Max |

M |

SD |

α

|

| To what extent did lecturers present the curriculum and the perseptions criteria clearly? |

1 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

4.05 |

.96 |

-- |

| To what extent did the supporting materials the lecturers gave me help with my studies? |

1 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.72 |

1.05 |

-- |

| Training structure |

2 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.89 |

.92 |

.812 |

| To what extent do I feel that I learned from the lecturers? |

1 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.94 |

.97 |

-- |

| To what extent did the perseptions methods enable me to display my knowledge? |

1 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.83 |

.97 |

- |

| My perseptions of my self-efficacy |

2 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.89 |

.88 |

.791 |

| To what extent did I receive autonomous support from the lecturers? |

1 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.75 |

1.13 |

-- |

| To what extent did the lecturer’s involvement help me? |

1 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

4.04 |

1.05 |

-- |

| General perseptions of the lecturers’ contribution to my training |

1 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.94 |

1.00 |

--

|

Validity of measures for structure and self-efficacy, as examined via Cronbach’s α, were high indicating a high level of stability and consistency in the responses of the participants for the statements of each measure. Table 2.2 displays the teachers’ responses to the various statements about their self-efficacy.

Table 2.2.

Characteristics, Mean, SD, & validity of statements of general self-efficacy (N=165).

Table 2.2.

Characteristics, Mean, SD, & validity of statements of general self-efficacy (N=165).

| Statement |

Min |

Max |

M |

SD |

| I can achieve most of my educational goals (achievement-orientation) |

2 |

5 |

4.28 |

.64 |

| When faced with tough educational tasks I’m sure I can do them (endurance) |

2 |

5 |

4.28 |

.67 |

| In general, I think I can achieve what’s important to me in teaching (task orientation) |

2 |

5 |

4.29 |

.69 |

| I can succeed in any educational task when I’m determined to do so (determination) |

3 |

5 |

4.40 |

.63 |

| I can deal successfully with many educational challenges (achievement-orientation) |

2 |

5 |

4.37 |

.64 |

| I can do most of my educational tasks well (task orientation) |

3 |

5 |

4.36 |

.63 |

| Even when things are tough I can do my educational work well (endurance) |

2 |

5 |

4.19 |

.70 |

| I’m confident I can do most of my educational tasks (confidence) |

3 |

5 |

4.37 |

.63 |

The self-perseptions of self-efficacy is evidently high for all the general statements examined, where determination ranked highest (4.40). This indicates perseverance, endurance, and very high self-perseptions of self-efficacy on the one hand, and on the other, the high score for all measures indicates teachers’ overestimation of their self-efficacy, which is impressive, given the complexity of the pandemic period.

Inferential statistics

To examine correlations between the evaluation of lecturers and overall self-efficacy, Pearson tests were conducted among each of the five measures of lecturer evaluation and the eight statements about self-efficacy. The results are shown in

Table 3.

Most coefficients are significant and positive, so we may say that the more the teachers appreciated their preservice training (and their lecturers), the higher their sense of self-efficacy. For gender differences in lecturer evaluation and overall self-efficacy, t-tests were performed for independent samples.

Table 4 presents the averages for both groups and the test results.

As

Table 4 shows, no significant differences were found for gender in either the measures of lecturer evaluation or the statements of overall self-efficacy. Hence, gender has no significant impact on the teachers’ perception of their professional self-efficacy or of their preservice training.

To examine correlations between age and seniority and the evaluation of lecturers and overall self-efficacy, Pearson tests were performed. The results are presented in

Table 5 below.

A positive correlation of weak but significant intensity was found between age and the measures of self-efficacy and autonomous support in the lecturers’ evaluation, so that the older the teacher, the higher the levels of self-efficacy and autonomous support. Positive correlations of weak intensity between age and the statement: "I can succeed in any educational task when I am determined" were also found, and positive correlations of weak intensity were found between seniority and most statements of overall self-efficacy. T-tests were performed for additional independent samples to examine differences between teachers with a master’s degree and those with a bachelor’s degree or teaching certificate only for the evaluation of lecturers and in overall self-efficacy,

Table 6 below presents the averages between the two groups and the results of the tests.

As shown above, teachers with a master’s degree reported that the lecturers presented the curriculum and evaluation criteria clearly, and that the course support materials provided by the lecturers helped them (structure index) more positively than teachers with a bachelor’s degree. Also, those with a master’s degree reported more autonomous support and lecturer involvement than those with a bachelor’s degree. Likewise, in all aspects of self-efficacy, which includes (mostly significantly) higher averages among teachers with a master’s degree than teachers with a bachelor’s degree and thus the more educated the teacher, the greater the perception of self-efficacy. The training is in-depth and optimal, affording a sense of empowerment. For differences according to family status (married/single) vis-à-vis lecturer evaluation and overall self-efficacy, T-tests were performed for additional independent samples.

Table 7 below presents the averages among the two groups and the results of the tests.

Table 7 shows that married teachers report they can achieve the educational goals they set for themselves to a significantly greater extent than single teachers. Likewise, married teachers feel they can perform the educational tasks they face significantly better than their unmarried counterparts. In the other aspects of overall self-efficacy, the average scores for married teachers are also higher than those of single teachers, but not significantly. In most of the lecturer evaluation indices, the average scores for married teachers is higher than those for single teachers (with the exception of the overall evaluation), but not significantly.

Summary of discussion and conclusions

The present investigation transpired during the apex of the COVID-19 pandemic, a period characterized by the closure of the education system in Israel for an extensive duration exceeding 130 days, necessitating the shift of all pedagogical activities to a remote format. In this exigent context, educators grappled with a myriad of intricate challenges, including the imperative to deliver instruction remotely from their residences and swiftly adapt to unfamiliar technological platforms (authors, 2022: Donitsa-Schmidt & Ramot, 2022). Over an eighteen-month span, educators operated within an ambiance rife with uncertainty, numerous constraints, and pervasive anxieties. This study was conceived to elucidate the nexus between teachers’ perceived self-efficacy and their retrospective reflections on the influence of their pre-service training on their current self-efficacy. The salience of this study resides in the examination of educators’ self-perceptions as a predictive variable for resilience during the intricacies of the pandemic. Evidently, self-efficacy emerges as a pivotal construct prognosticating teachers’ adeptness in navigating the challenges intrinsic to their vocation, fostering student empowerment, and withstanding diverse circumstances necessitating both professional and personal resilience.

The study posited the following research inquiries:

Is there a discernible correlation between antecedent training experiences and the contemporary sense of self-efficacy?

How do educators appraise their self-efficacy amid the scrutinized pandemic period?

Which factors exert influence on educators’ self-efficacy assessments, and which of these influences remain unverified?

The empirical findings evince a noteworthy correlation between educators’ retrospective evaluations of their pre-service training, particularly in relation to their instructional mentors, and their extant self-efficacy. Educators rendered high appraisals of their self-efficacy during the pandemic, thereby attesting to their resilience in a convoluted epoch marked by profound uncertainty and characterized by exigent personal and professional adaptations (Pressley & Ha, 2021).

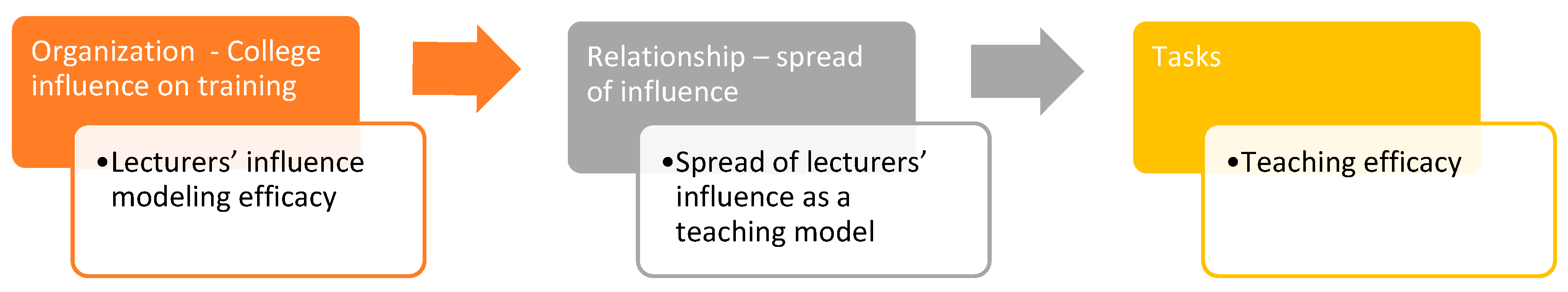

These findings led to the creation of a model depicting the chain of influences that, in our opinion, created the teachers’ high perceptions of their own competence (

Figure 1).

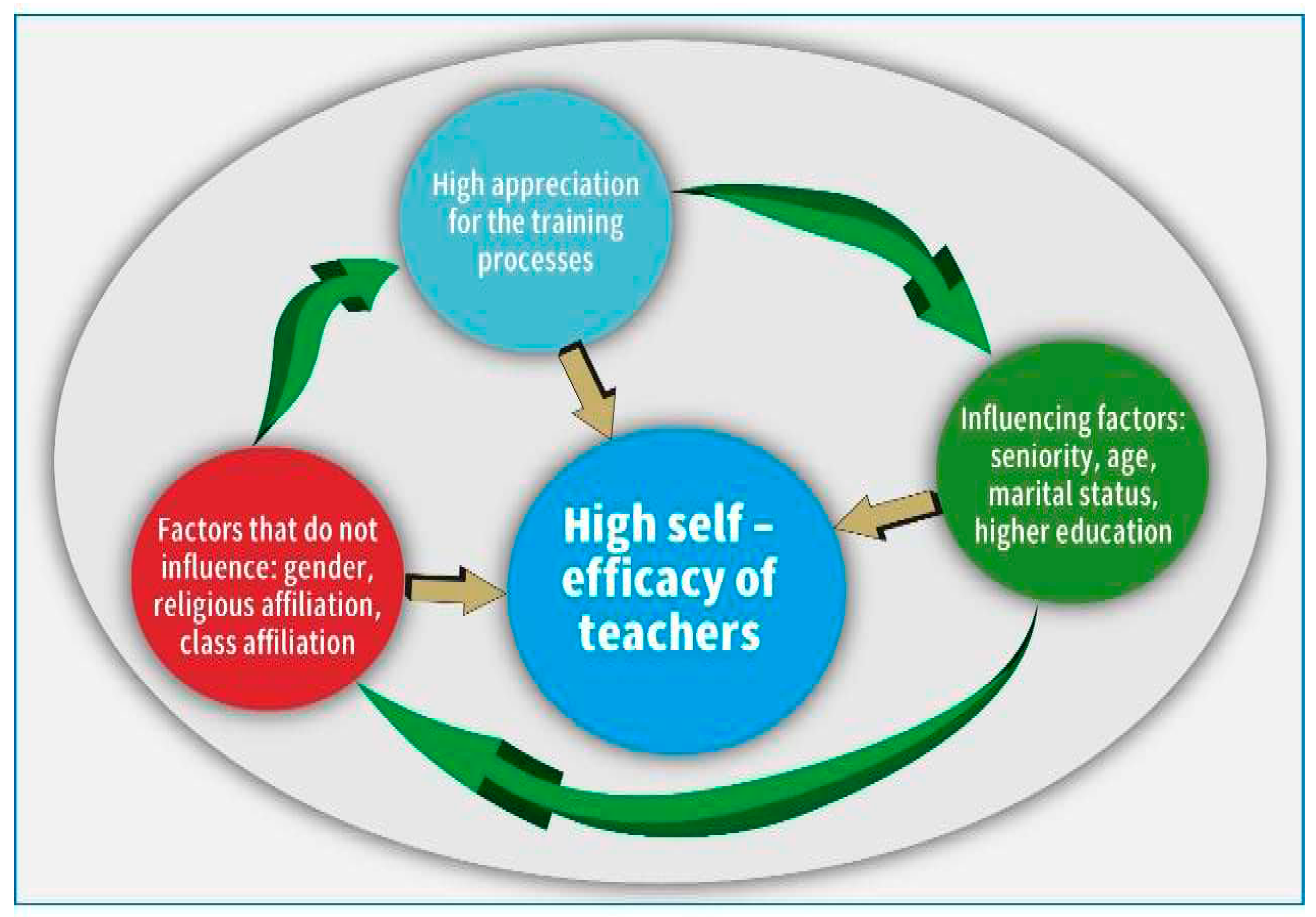

Likewise, the picture of the connections emerges as follows: the teachers’ retrospective perceptions of their preservice training indicates that the more they appreciate their training as positive and the more they value the lecturers, the greater their sense of self-efficacy. Seniority and marital status emerged as variables also positively influencing the sense of self-efficacy. The perception of self-efficacy develops with time and the experience of seniority. The more educated the teachers, the greater their sense of self-efficacy. The current study shows that the factors influencing the teachers’ high sense of self-efficacy are: good training from good lecturers appreciated by their students, as well as seniority, age, marital status, and higher education (master’s degree and CPD). On the other hand, the variables of gender and socioeconomic status had no effect on the self-efficacy of the teachers sampled.

Figure 2 encapsulates these insights.

A primary inference drawn from this study is the discernible influence of effective lecturers in shaping proficient educators. Educators exhibiting robust self-efficacy and a positive appraisal of their training, even under exigent circumstances such as a state of emergency, play a pivotal role in fostering enhanced coping mechanisms among their pupils. This, in turn, contributes to systemic resilience within the educational framework. These findings, albeit partially congruent with antecedent studies, affirm the pivotal role of educators in cultivating students’ adaptive capacities, particularly in times of crisis.

The present study aligns, in part, with prior research, notably that of Friedman and Kass (2000), who identified three dimensions constituting teachers’ professional efficacy in Israel: the task, the relationship, and the organizational aspect. Moreover, teachers’ personal efficacy perception is subject to external influences, including interpersonal relationships within the school organization, especially with school leaders such as principals, and the capacity to effect change within the school milieu. In the distinctive context of the pandemic, these dimensions assumed heightened significance and likely exerted substantial influence on educators’ self-efficacy, thereby impacting their overall effectiveness or conversely, engendering dissatisfaction and a proclivity towards professional attrition (Granziera & Perera, 2019). This nexus is pivotal for teaching quality, student support, and educators’ well-being (Zee & Koomen, 2016).

The insights from Ayllón et al. (2019) complement the study’s findings by elucidating the salient role of teachers and their pupils’ self-efficacy as two intrinsically linked elements with a robust positive correlation to academic achievements. Students attain higher grades when they perceive their teachers as reliable sources of support and resources and when they possess the confidence to organize and implement requisite actions for knowledge acquisition. The enduring impact of teacher-student interactions, whether in the context of young pupils and their teachers or college students and their lecturers, emerges as highly significant, persisting even years after the conclusion of formal study and training. This enduring influence on retrospectively perceived self-efficacy holds broad implications for personal and professional resilience, particularly in times of uncertainty. This is in line with Narayanan et al (2022) that have noted that Self-reflection is part of a necessary meaning making process that supports teacher in their professional challenge. Notably, the present study attests to educators’ unwavering faith in their self-efficacy and professional capabilities amidst the formidable challenges of the examined period, a sentiment congruent with the recent findings of Wang (2022).

Research limitations

The questionnaire was sent to teachers who had completed their studies in the previous decade, from a distance of time, retrospective perseptions is subjective and relies on memories. On the other hand, the impact of lecturers who are remembered indicates a significant impact.

References

- Aktaş, B. Ç. (2018). Perseptions of induction to teaching program: Opinions of novice teachers, mentors, school administrators. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(10), 2101–2114. [CrossRef]

- Aran, Z., & Zaretsky, R. (2017). Academy-Class as promoting self-efficacy in teaching – A comparative study. Michlol, 32. (Hebrew).

- Arnon, R., Frankel, P., & Rubin, E. (2015). Why should I be a teacher? Positive and negative factors in choosing a teaching career, Dapim, 59, 11-44. (Hebrew).

- Ayllón S., Alsina Á., & Colomer, J. (2019) Teachers’ involvement and students’ self-efficacy: Keys to achievement in higher education. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0216865. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1995). Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies, 15, 334.

- Baroudi, S., & Shaya, N. (2022). Exploring predictors of teachers’ self-efficacy for online teaching in the Arab world amid COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 8093-8110. [CrossRef]

- Berger, N., Mackenzie, E., & Holmes, K. (2020). Positive attitudes towards mathematics and science are mutually beneficial for student achievement: A latent profile analysis of TIMSS 2015. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47, 409-444. [CrossRef]

- Billett, P., Turner, K., & Li, X. (2023). Australian teacher stress, well-being, self-efficacy, and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology in the Schools, 60(5), 1394-1414.

- Burić, I., and Kim, L. (2020). Teacher self-efficacy, instructional quality, and student motivational beliefs: An analysis using multilevel structural equation modeling. Learning and Instruction, 66, 101302. [CrossRef]

- Czerniawski, T., Ma, J. W., & Leite, F. (2021). Automated building change detection with a modal completion of point clouds. Automation in Construction, 124, 103568.

- Davis, B. H., & Waite, S. H. (2003). The long-term effects of a public school/state university Induction program. The Professional Educator, 2(1). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ773849.pdf.

- Donitsa-Schmidt, S., & Ramot, R. (2022). Opportunities and challenges: Teacher education in Israel in the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 586-595. [CrossRef]

- Dror, Y. (2016). Three decades of teacher education in Israel and their impact on the professional development teacher educators. In: A. Adi-Rakach, & U. Cohen (Eds.), Dynamism in higher education: Anthology of articles in honor of Prof. Avraham Yogev (pp. 189-213). Tel Aviv university (Hebrew).

- Ekin, S. (2018). The effect of vision/imagery capacity of the foreign language learners on their willingness to communicate (Doctoral dissertation, Hacettepe Universitesi (Turkey).

- Fridman, Y., & Kass, E. (2000). The teachers sense of self-efficacy - the concept and its measurement. Henrietta Szold Institute. (Hebrew).

- Granziera, H., & Perera, H. N. (2019). Relations among teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, engagement, and work satisfaction: A social cognitive view. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 75-84.

- Herman K. C., Sebastian J., Reinke W. M., Huang F. L. (2021). Individual and school predictors of teacher stress, coping, and wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic. School Psychology, 36(6), 483-493. [CrossRef]

- Izadinia, M. (2014). Teacher educators’ identity: A review of literature. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(4), 426-441. [CrossRef]

- Kee, B., & Aye, S. (2020). A study of the attitude of pre-service teachers in education colleges towards their teaching profession (Doctoral dissertation, MERAL Portal).

- Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2011). The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: Influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(2), 114-129. [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59-76. [CrossRef]

- Makdosi, O., (2018). From Academy to classroom: Examining a training model and the pattern of integration into teaching in three education sectors. A study presented at a seminar on Researching the Academy-Class Program, MOFET Institute. (Hebrew). MOFET Institute. (Hebrew).

- Marschall, G., & Watson, S. (2022). Teacher self-efficacy as an aspect of narrative self-schemata. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 103568. [CrossRef]

- Author, et al., (2020).

- Narayanan, M., & Ordynans, J. G. (2022). Meaning making and self-efficacy: Teacher reflections through COVID-19. The Teacher Educator, 57(1), 26-44. [CrossRef]

- Author, et al (2023).

- Authors. (2020).

- Orland-Barak, L. and Wang, J. (2020). Teacher mentoring in service of preservice teachers’ learning to teach: Conceptual bases, characteristics, and challenges for teacher education reform, Journal of Teacher Education, 72(1), 86-99.

- Pressley, T., & Ha, C. (2021). Teaching during a pandemic: United States teachers’ self-efficacy during COVID-19. Teaching and Teacher Education, 106, 103465. [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T., Roehrig A. D., & Turner J. E. (2018). Elementary teachers’ perceptions of a reformed teacher evaluation system. The Teacher Educator, 53(1) (2018), pp. 21-43. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D., & Becker, E.S. (2021). Situational fluctuations in student teachers’ self-efficacy and its relation to perceived teaching experiences and cooperating teachers’ discourse elements during the teaching practicum. Teaching and Teacher Education, 99), 103252. [CrossRef]

- eachers’ Emotions and Self-Efficacy: A Test of Reciprocal Relations. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343958314_Teachers’_Emotions_and_Self-Efficacy_A_Test_of_Reciprocal_Relations [accessed Nov 27, 2022].

- Tümkaya, G. S., & Miller, S. (2020). The perceptions of pre- and in-service teachers’ self-efficacy regarding inclusive practices: A systematised review. Ilkogretim Online, 19(2). [CrossRef]

- VanLone, J., Pansé-Barone, C., & Long, K. (2022). Teacher preparation and the COVID-19 disruption: Understanding the impact and implications for novice teachers. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100120. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. (2022). Exploring the relationship among teacher emotional intelligence, work engagement, teacher self-efficacy, and student academic achievement: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 810559. [CrossRef]

- Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981-1015. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).