1. Introduction

Depression is a major global mental health problem worldwide [

1]. It is common and often recurrent, with a global prevalence of 4% in school-aged children, and 7.5% in adolescents [

1,

2]. Depression symptoms often co-occur with anxiety disorders [

2] and a range of somatic symptoms and signs, particularly early in life. There is an association between somatic complaints and mental disorders. As depression is very often associated with other disorders, it is no longer clear what is the cause and what is the effect.

Recent studies have reported that increasing physical activity is recognized as a potential target for preventing the onset of depression [

3] and for reducing the symptoms of depressive and anxiety disorders, especially for in those affected by mild to moderate depression [

4].

Ventricular extrasystoles (VE) are one of the most common arrhythmias occurring in patients with heart abnormalities as well as in healthy children [

5]. Although idiopathic ventricular extrasystoles in children are considered as benign, about one third of patients experience somatic symptoms [

6] and have limitations in physical activity. Recent studies have shown that patients with VE have lower exercise capacity than healthy children [

7].

The problem of having an arrhythmia can be distressing for children and their parents. During the process of arrhythmia evaluation and monitoring, these patients require many outpatient and/or inpatient care visits, which is stressful for patients and their parents. Heart rhythm disturbances are sensitive problem because most of the parents and patients associate arrhythmias with the risk of sudden cardiac death. Therefore, children with heart rhythm problems are at risk of parental overprotection. Overprotective parents tend to restrict physical activity, and previous work has found an association between overprotective parenting styles and anxiety and depression in children [

8].

Our study was conducted to determine the relationship between somatic symptoms, signs of depression, and physical activity levels in children with idiopathic VE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedure

The prospective study of children with structurally normal hearts and VE was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee No. 2021/10-1383˗859(1). The inclusion criteria were 3-17 years old children with and/or more than 5% VE per 24 hours and/or group, and/or multiform VE. The exclusion criteria were diagnoses of hemodynamically significant heart diseases, channelopathies. The study was performed in Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Clinics from 1st January 2022 to 30th August 2023. The authors designed Questionnaires to assess patients’ age, biological gender, symptoms, physical activity, depression symptoms. Children aged ≥12 years old and parents who assessed their children's condition completed the questionnaires. All children underwent 24-hour electrocardiogram and echocardiography to evaluate arrhythmia frequency and their cardiac condition.

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Assessment of Symptoms

The questionnaires included questions on symptoms such as chest pain, palpitations, syncope/fainting, weakness, fatigue, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance. Respondents rated the frequency of the symptoms and the relationship between the symptoms and physical activity as never/ rarely/ sometimes/ often/ very often. The answers sometimes/ often/ very often were scored as having symptoms or relationships respectively.

2.2.2. Assessment of Physical Activity

We assessed the amount of time per week spent on physical activity. The questionnaires included questions about the amount of time per week spent in physical education at school and extra-time spent in sport activities. We divided the children into groups according to the amount of time spent in physical activity: up to 6 hours per week- leisure activity, 6-10 hours per week- competitive sportsmen, and more than 10 hours per week- elite sportsmen.

2.2.3. Assessment of Depression Symptoms

Symptoms and depression were evaluated using a modified pediatric version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is a well-validated, criterion-based measure for diagnosing depression, assessing severity and monitoring treatment response [

9]. The PHQ-9 score can range from 0 to 27, with each of the 9 items scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day) [

9]. The interpretation: ≤4 - no signs of depression; 5-9 - mild depression; 10-14 - moderate depression; ≥15 - severe depression. The PHQ score of ≥10 has been reported to have both a sensitivity and specificity of 88% for major depression [

9].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software. Nominal variables were tested for normal distribution with Shapiro-Francia test. Normally and non-normally distributed variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median, minimum, and maximum values respectively. Categorical variables were presented as numbers (percentages). Comparisons of continuous variables between different groups were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test according to the distribution. Comparisons of categorical variables were made using the chi-square or Fisher's exact test, respectively. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Patients

Questionnaires were completed by 60 parents of children and 39 children aged >12 years. The median age of the patients was 13 (5-17) years.

The latest tested VE count median was 4.77 (0.1 - 32.77) % per 24 hours. Maximal achieved VE count median was 6.73 (0.34 - 34,47) % per 24 hours. All children had hemodynamically normal hearts. The median left ventricular function assessed by Simpson’s biplane method and was in the normal range - 61.5 (55.4 - 70.7) %.

The main characteristics of the patients are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Symptoms

Twenty-seven patients were asymptomatic. Parents rated the MP-PHQ-9 of their asymptomatic children statistically significantly better (p=0.03). There were no MP-PHQ-9 scores higher than 10 in asymptomatic children.

The most common symptom was palpitations. Chest pain was experienced by older children (median age - 16 years vs 12 years old; p=0.01) with no difference between age and other symptoms.

Patients with symptoms demonstrated significantly higher median children’s MP-PHQ-9 scores than those without symptoms: with palpitations 8 vs 3 (p=0.01); chest pain 10 vs 3 (p=0.01); dyspnea 12 vs 3 (p=0.003); exercise intolerance 10 vs 3 (p=0.03). There was no difference between children with syncope/fainting and children’s MP-PHQ-9 scores (p=0.61).

Patients with more than 2 symptoms were less physically active (1.5 vs 3.75 hours/week; p=0.009). Adolescents with more than two symptoms were more likely to have a higher MP-PHQ-9 score (

Table 2).

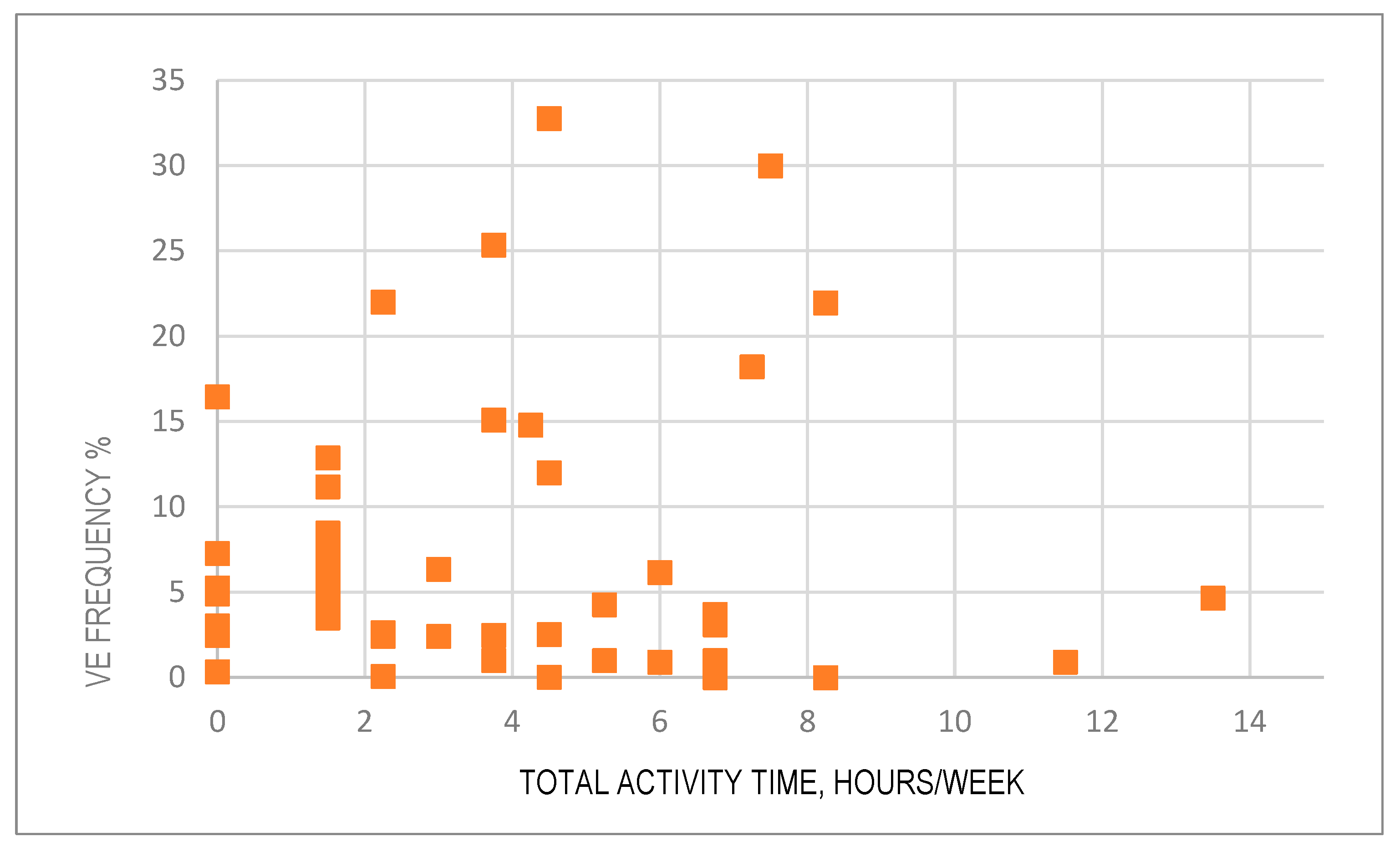

3.3. Physical Activity

The median total time of physical activity was 3.75 (1.5-28.75) hours per week. The median physical activity during school time was 2.25 (1.5-7.5) hours per week. Thirty-one (51.7%) children participated in extra-sports with a median extra-sports activity time of 3.75 (0.75-25) hours per week.

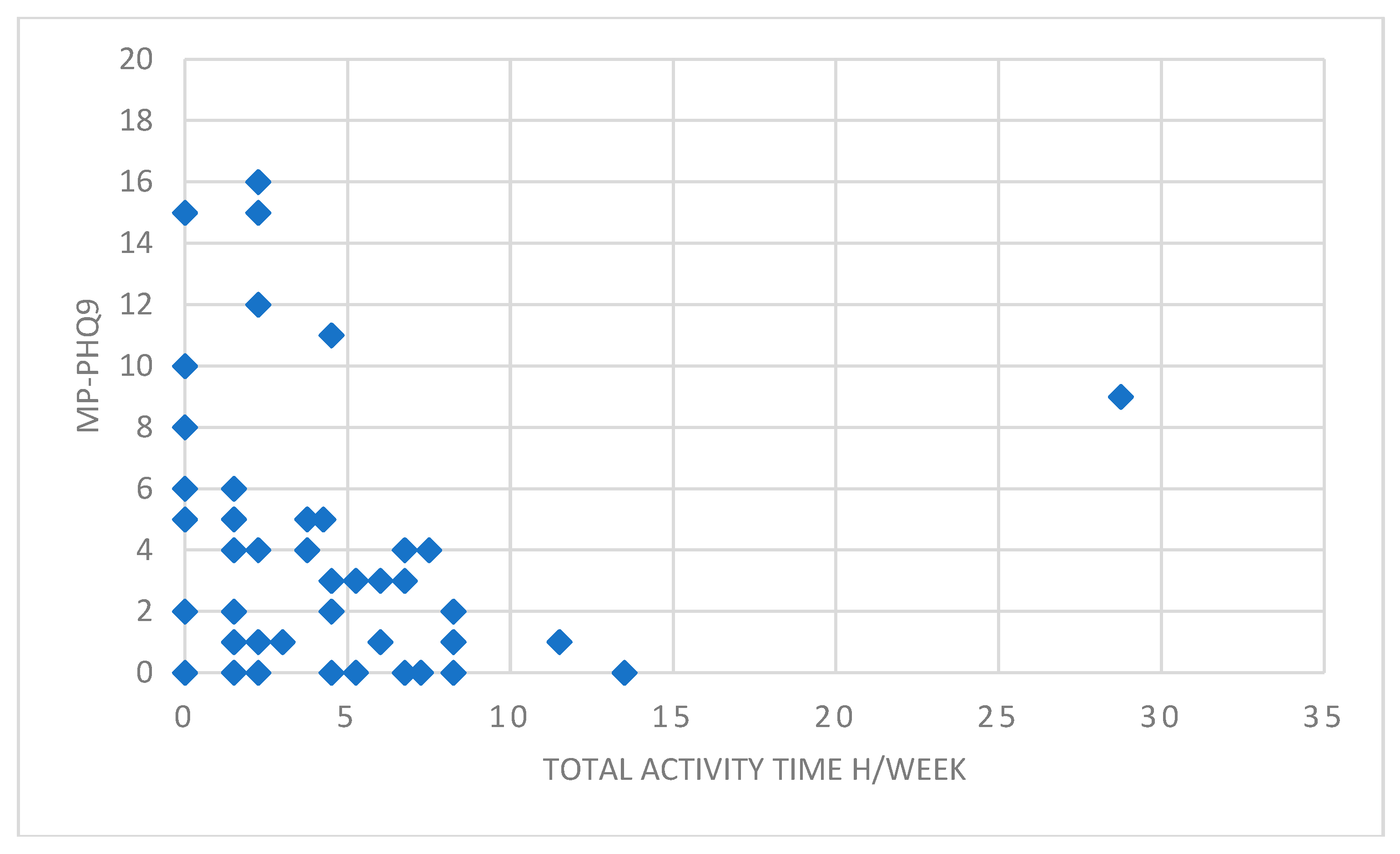

The physical activity time was not related to the frequency of VE. (

Figure 1)

Physical activity of 11 (18.3%) patients was suspended. However, one patient continued to participate in competitive sports.

3.4. Depression Symptoms

The median score of the MP-PHQ-9 completed by parents was 2 (0-16) and by children - 4 (0-18). Parents statistically significantly underestimated their children's depressive symptoms (p<0.005) (

Table 1).

Three patients had the MP-PHQ-9 scores greater than 15. Eight patients had MP-PHQ-9 scores higher than 10, two of them were suspended from physical activity, two of them participated in leisure extra-sports.

Patients with MP-PHQ-9 scores higher than 10 had total physical activity of less than 5 hours/week (

Figure 2).

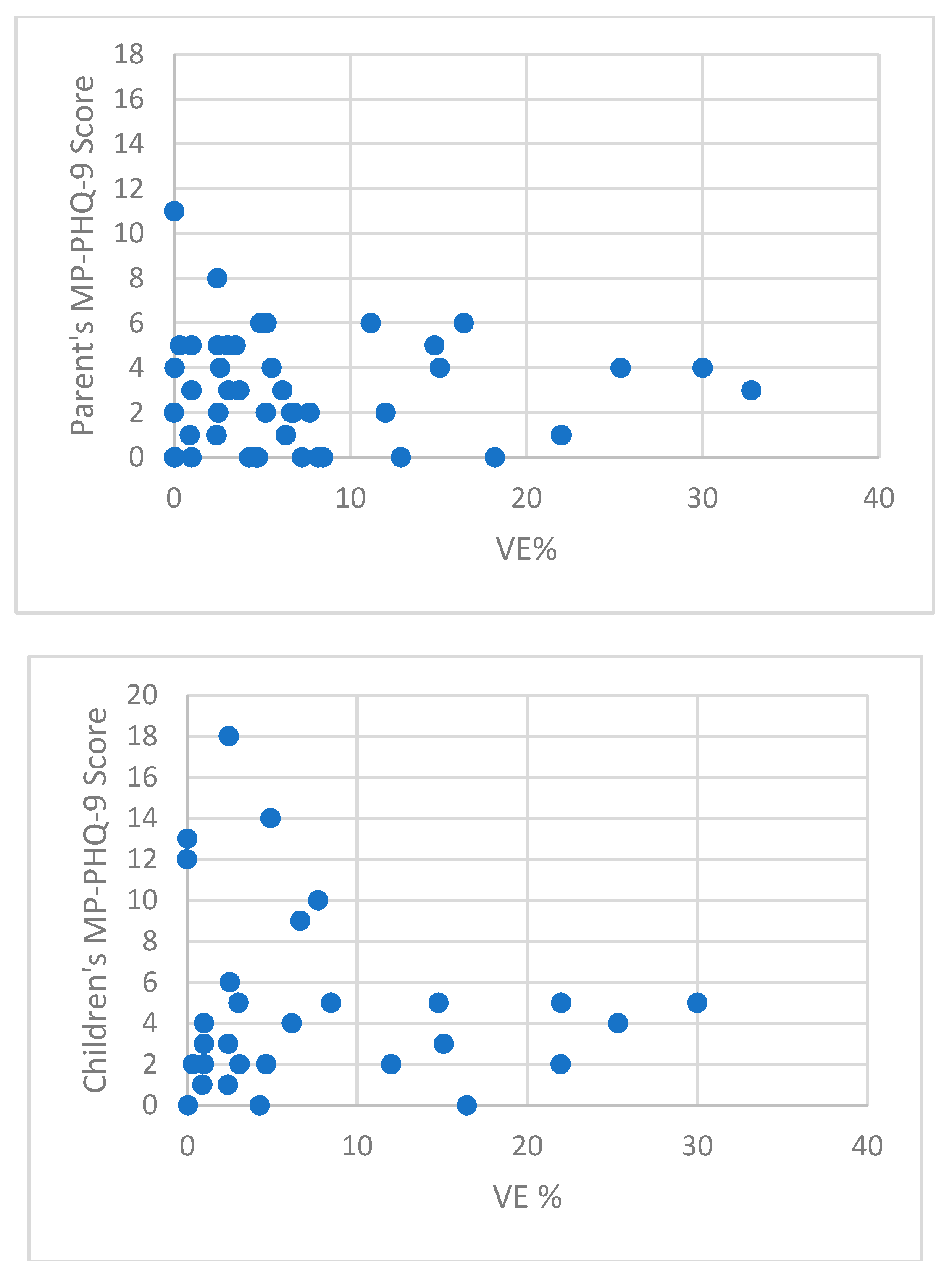

There were no significant differences between the counts of VE, and Questionnaire results (p>0.05) (

Figure 3).

The comparison between parents’ and children’s median MP-PHQ-9 scores is shown in

Table 2.

Figure 2.

The relationship between MP-PHQ-9 scores and total physical activity time.

Figure 2.

The relationship between MP-PHQ-9 scores and total physical activity time.

Figure 3.

The relationship between MP-PHQ-9 scores and VE% (p>0.05).

Figure 3.

The relationship between MP-PHQ-9 scores and VE% (p>0.05).

4. Discussion

Children with chronic health conditions often have emotional and mood disorders. Although pediatric idiopathic VE is considered benign, in our study 8.3% of patients showed signs of moderate depression and 5% showed signs of severe depression. According to Shorey et al. meta-analysis of the general population of adolescents, 8% had major depressive disorder, and 34% had depressive symptoms [

10].

Early identification of depressive symptoms is associated with better recognition of the problem and more effective treatment. The role of the family in recognising early signs of depression is unquestionable. Family members are very important as direct and indirect models of emotional understanding and communication [

11]. However, our research has shown that parents underestimate the signs of depression in their children.

Many studies in children and adolescents have shown an association between depression and complaints of somatic symptoms [

12]. For example, fatigue is strongly associated with depression [

12]. On the other hand, other types of somatic symptoms seem to be more strongly associated with anxiety (e.g., chest pain) [

12]. In our study the children who experienced symptoms of palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance demonstrated significantly higher depression scores. In addition, more somatic symptoms were associated with higher levels of depression in our study.

Data from different authors have shown that between 23% and 48.5% of children with VE experience somatic symptoms [

6,

13,

14] such as palpitations, fainting, fatigue, chest pain or syncope [

14]. In our study, 45% of the children had symptoms. This can be explained by the assessment of somatic symptoms according to their frequency of their occurrence. In our study, palpitations were the most frequent symptoms.

Physical activity plays an important role in the prevention of mental health problems [

15]. Meta-analyses demonstrate that participation in physical activity leads to a significant reduction in symptoms of depression in people with established depression, suggesting a role for physical activity as part of therapeutic interventions [

15]. A recent population meta-analysis found that people with high levels of physical activity had 17% lower odds of depression than people with low levels of physical activity [

15,

16]. Low physical activity is also associated with a higher risk of depression [

16]. In our study, adolescents who were active less than 5 hours/week active were at risk of moderate depression symptoms. There was no evidence of moderate or severe depression in competitive and elite sportsmen groups. The World Health Organization recommends 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day for 5-17 years old children. This equates to 5-7 hours per week. Only 40% of the children in our study met the World Health Organization guidelines for physical activity [

17].

The strength of our study is its prospective nature. We assessed the association between somatic complaints, depression scores and physical activity time in children with ventricular extrasystoles, which are usually considered benign. We scored somatic symptoms according to their frequency of occurrence. The amount of physical activity was assessed in hours per week. Therefore, we did not assess the exertion during physical activity using diaries, activity scales or pedometers. Our study also had other limitations. The number of patients included in the study was limited, and the observation period was not long enough, so there is a possibility of error. We did not conduct a double- blind study so the results may be susceptible to selection bias. Due to the limited number of patients with depression symptoms, the risk factors could not be properly assessed.

5. Conclusions

Idiopathic ventricular extrasystoles, limitations in physical activity and depression remain the actual theme for clinicians and need further research. In our study, children who were physical active less than 5 hours per week had higher depression risk scores. Patients with somatic symptoms had higher depression scores.

It is still controversial how somatic symptoms and depression determine the intensity of physical activity in a group of patients with idiopathic ventricular extrasystoles. It is not clear whether they are a cause or a consequence of depression. However, it is important that an association was found between depression, somatic symptoms, and physical activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, design, supervision, and project administration, R.K., O.K. V.U.; Collecting data for the study, R.K. Formal analysis, development of methodology, investigation, verification, and validation R.K. and O.K. Writing the original draft of the manuscript, R.K. Review and editing the manuscript, O.K., V.U., and. S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Scientific Research funded by Vilnius University as a part of PhD studies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee No. 2021/10-1383˗859(1).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consents were obtained directly from all patients or their relative as required by Regional Requirements.

Data Availability Statement

On request, the corresponding author will provide the datasets produced and/or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly welcome the participation of the patients and their relatives who took part in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Marwaha S, Palmer E, Suppes T, Cons E, Young AH, Upthegrove R. Novel and emerging treatments for major depression. Lancet. 2023 Jan 14;401(10371):141-153. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Muñoz I, Mallikarjun PK, Chandan JS, Thayakaran R, Upthegrove R, Marwaha S. Impact of anxiety and depression across childhood and adolescence on adverse outcomes in young adulthood: a UK birth cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2023 May;222(5):212-220. [CrossRef]

- Kim SY, Park JH, Lee MY, Oh KS, Shin DW, Shin YC. Physical activity and the prevention of depression: A cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019 Sep-Oct;60:90-97. [CrossRef]

- Helgadóttir B, Forsell Y, Ekblom Ö. Physical activity patterns of people affected by depressive and anxiety disorders as measured by accelerometers: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015 Jan 13;10(1):e0115894. [CrossRef]

- He YE, Xue YZ, Gharbal A, Qiu HX, Zhang XT, Wu RZ, Wang ZQ, Rong X, Chu MP. Efficacy of radiofrequency catheter ablation for premature ventricular contractions in children. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2021 Apr;60(3):535-542. [CrossRef]

- Chen B, Li J, Li S, Fang Y, Zhao P. Risk Factors for Left Ventricle Enlargement in Children With Frequent Ventricular Premature Complexes. Am J Cardiol. 2020 Sep 15;131:49-53. [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak R, Łuczak-Woźniak K, Książczyk TM, Werner B. Cardiopulmonary capacity is reduced in children with ventricular arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm. 2023 Apr;20(4):554-560. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A., Kegley, M., & Klein, D. N. (2022). Overprotective Parenting Mediates the Relationship Between Early Childhood ADHD and Anxiety Symptoms: Evidence From a Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 26(2), 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino E, Ohde S, Rahman M, Takahashi O, Fukui T, Deshpande GA. Variation in somatic symptoms by patient health questionnaire-9 depression scores in a representative Japanese sample. BMC Public Health. 2018 Dec 27;18(1):1406. [CrossRef]

- Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022 Jun;61(2):287-305. [CrossRef]

- Freed RD, Rubenstein LM, Daryanani I, Olino TM, Alloy LB. The Relationship Between Family Functioning and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: The Role of Emotional Clarity. J Youth Adolesc. 2016 Mar;45(3):505-19. [CrossRef]

- Gibson RC, Lowe G, Lipps G, Jules MA, Romero-Acosta K, Daley A. Somatic and Depressive Symptoms Among Children From Latin America and the English-Speaking Caribbean. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023 :13591045231178890. 25 May. [CrossRef]

- West L, Beerman L, Arora G. Ventricular ectopy in children without known heart disease. J Pediatr. 2015 Feb;166(2):338-42.e1. [CrossRef]

- Bertels RA, Kammeraad JAE, Zeelenberg AM, Filippini LH, Knobbe I, Kuipers IM, Blom NA. The Efficacy of Anti-Arrhythmic Drugs in Children With Idiopathic Frequent Symptomatic or Asymptomatic Premature Ventricular Complexes With or Without Asymptomatic Ventricular Tachycardia: a Retrospective Multi-Center Study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2021 Apr;42(4):883-890. [CrossRef]

- Dimitri P, Joshi K, Jones N; Moving Medicine for Children Working Group. Moving more: physical activity and its positive effects on long term conditions in children and young people. Arch Dis Child. 2020 Nov;105(11):1035-1040. [CrossRef]

- Kandola A, Ashdown-Franks G, Hendrikse J, Sabiston CM, Stubbs B. Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019 Dec;107:525-539. [CrossRef]

- WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).