1. Introduction

The Environmental, Social/Sustainable, and Governance (ESG) rating and performance of a company affect its market value (Ward and Wu, 2019). On the supply side, a company may obtain government subsidies and/or reductions in levies by improving the firm’s ESG scores, while on the demand side, stocks with high ESG performance attract ESG-conscious individuals and norm-constrained institutional investors. Moreover, investors whose focus is on risk-adjusted returns can further fuel demand for stocks with high ESG ratings should the scores be priced in the market. All the above factors combine to produce a positive feedback loop, which in effect can create a win-win situation for the high ESG rated companies and their shareholders which include ESG advocates, profit-oriented agents, and ESG norm-constrained and -unconstrained institutional investors. Consequently, firms with high ESG ratings have a lower cost of equity capital and a higher valuation than those at the other end of the measure. The existence of the ESG premium in firm values can propel both financial and real production activities to align economic goals with social welfare objectives.

Given these conjectures, we postulate that firms with high ESG ratings are more resilient to market volatility than those with low ESG ratings. Particularly, the preference for high ESG firms makes them less susceptible to selling pressure in stressful market situations as the ESG-conscious clientele (investors) are less prone to speculative trading; in addition, the speculative value of such firms is limited since they are already priced at a premium and less attractive to speculators. Using the recently introduced ESG weight-tilted Hang Seng Index (HSIESG), this study also documents the performance of the two indexes and examines whether the return pattern of HSIESG differs from its parent Hang Seng Index (HSI) under extreme market volatility conditions.

The value-weighted free-float-adjusted HSI is the gauge of the blue-chip stocks listed on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong (SEHK). The index is also the underlying of the first Hong Kong index exchange-traded fund (ETF)—that is, the Tracker Fund. The HSIESG is constructed by shifting the original HSI portfolio weights from the lower to higher ESG-rated firms while maintaining the set of constituent stocks of the parent index. The tilts are based on the ESG scores provided by the Hong Kong Quality Assurance Agency (HKQAA). These features allow a direct test of the impact (if there is any) of the tilted weights on the performance and volatility-return characteristics of the ESG-infused index relative to its parent.

However, unlike the highly distinguishable ESG-driven performance differential of a best-in-class index compared to its broad-based parent index such as the S&P 500 (Giese et al., 2019), we expect it would be difficult to discern how the tilted weights affect the performance of the narrow-based HSI because the ESG-infused index and parent index are highly correlated. Moreover, Friede, Busch, and Bassen (2015), in their comprehensive meta-analysis, document a weak correlation between ESG and the performance of equities investments, a finding that further lowers the expectation that the HSIESG can significantly outperform the parent index. Indeed, our study finds that the returns of the weight-tilted HSIESG and the parent index have a correlation of over 99%, which explains why only minor improvements in the performance metrics (mean and volatility of returns) are found in the weight-tilted index. Nevertheless, the paper shows a subtle but significant negative and asymmetrical relationship between the average returns of the two indexes and the change in index option implied market volatility. The asymmetrical volatility-return relationship is defined by an observation that the positive return associated with a drop in volatility is less than the magnitude of the negative return triggered by an equal rise in volatility.

We find that the returns in both indexes have a negative relationship with changes in the VHSI (HSI Volatility Index), a common proxy for movements in current and perceived future market volatility. Most important, this study finds that the response to the volatility of the ESG-infused index return is significantly weaker than that of the parent index during volatile periods, a crucial phenomenon that led to the substantially higher holding period return of the HSIESG than that of the HSI. This result supports the proposition that firms with high ESG ratings are less susceptible to trading pressures triggered by volatility-induced turnovers. The evidence also shows that the ESG weight-tilted index is more resilient to volatility spikes than the parent index, indicating that stocks with high ESG ratings can be a hedge against market downside risks. This paper contributes to the literature by providing significant incremental information on the emerging market for ESG-related equity products in Hong Kong.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related studies.

Section 3 describes the data and methodology for the empirical analysis.

Section 4 summarizes and interprets the findings. Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evidence of the Market’s Preference for ESG-Related Financial Products

The International Monetary Fund (2019) finds that the demand for ESG equity investment funds has accelerated in recent years. Conversely, Brown Brothers Harriman’s (2019) survey reveals that ESG ETFs are among the top five ETF sectors that investors prefer to be available in the Hong Kong market. Furthermore, Moody’s (2020) study finds that stock indexes attract greater interest when the data compiler incorporates ESG factors in the index products. As ESG-related securities attract fund flows, the funding costs and capital constraints of firms with high ESG ratings can be substantially reduced through the issuance of equity securities. Consequently, the lower required return produces healthier valuations of the stocks and creates for investors higher risk-adjusted returns.

Wu and Juvyns (2020) show that the growth in fund flows into ESG-related equities was uninterrupted by the economic and financial turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, in the United States during Q1 2020, ESG-related open-end mutual funds and ETFs received close to US$10 billion of capital inflows, an amount that is more than half of the total for the full year of 2019. During the same period, the market for ESG ETFs experienced only two weeks of insignificant outflows and the MSCI ESG Leaders Indexes outperformed their extremely volatile market benchmarks (Authers, 2020). The above findings show that the prices of ESG-related equity products can weather the downside pressure with the support of norm-constrained institutions and ESG-advocate investors in general.

2.2. The Preference for ESG-Infused Index Funds

Giese et al. (2019) emphasize the benefits to investors in incorporating ESG scores in index construction as the ESG-tilted index portfolio combines the value of ESG and passive investment in a high-quality well-diversified portfolio. The available ESG-tilted index portfolios can attract large-scale investing toward companies with high ESG ratings, which creates a positive feedback effect, as good ESG practices increase demand for the ESG portfolio and enhance the risk-adjusted return. Conversely, if ESG practices can improve the risk-adjusted return to investors, then ESG-infused financial products and index funds or ETFs appeal also to investors whose main focus is on the potential financial benefits rather than social benefits (Giese et al., 2019), an aspect that can further fuel the demand for ESG-related index products.

2.3. Potential Financial Benefits from Investing in Companies with High ESG Ratings

An extensive number of studies have examined the association between ESG ratings and firms’ financial performance. Friede, Busch, and Bassen (2015) provide a comprehensive meta-analysis that covers over 2,200 primary studies and survey articles published over a 40-year period since 1970. The study shows that over 62% of the primary studies find a positive relationship between ESG rating and corporate financial performance (CFP); the relationships are stable over time and are stronger for emerging markets. The CFP metrics used in the meta-analysis include accounting and market-based risk-return measures.

Gregory, Tharyan, and Whittaker (2014) argue that high ESG ratings and performance improve cash flows to shareholders, as ESG attributes strengthen a firm’s competitiveness, which raises the company’s profitability and dividends. Their argument is consistent with Fatemi, Fooladi, and Tehranian’s (2015) findings that high-ESG firms are more likely than those in the low-ESG group to attract and retain dedicated employees and loyal customers. Dunn, Fitzgibbons, and Pomorski (2017) show that the MSCI ESG rating is positively associated with the firm’s financial performance but negatively related to its risk. To address the correlation-versus-causality criticism made by Krueger (2015), Giese et al. (2019) provide an empirical analysis of economic explanations of causality. Pulino et al. (2022) report a positive relationship between ESG disclosure and firm performance (measured by EBIT) for large Italian companies. Wasiuzzaman et al. (2022) suggest that regulators should include cultural dimensions in the development of a single global standard for ESG disclosure. Using data from G20 countries, Bissoondoyal-Bheenick et al. (2023) show that large firms tend to invest more in ESG activities and have better media coverage than small firms. This reduces the information asymmetry of major enterprises regarding ESG investments for their stakeholders.

Eccles, Ioannou, and Serafeim (2014) argue that ESG reduces systematic risk, as firms with strong ESG characteristics are less susceptible to market-wide shocks due to improvement in operational efficiency. Therefore, such companies have lower costs of capital than those with weak ESG performance. Hong and Kacperczyk (2009) and El Ghoul et al. (2011) show that the cost of capital can also be manifestation of information transparency and such firms are favored by norm-constrained institutional investors. Godfrey, Merrill, and Hansen (2009) and Oikonomou, Brooks, and Pavelin (2012) report that ESG reduces financial risk, as a firm with a stronger ESG profile has higher compliance standards and better risk management, is therefore less vulnerable to idiosyncratic and operational risks than the counterparts. This allows high ESG firms to avoid costly lawsuits and settlements. Giese et al. (2019) also find among MSCI-rated firms that companies with high–MSCI ESG ratings have reduced idiosyncratic risk and an increased buffer against market risk. Lins, Servaes, and Tamayo (2017) show that social responsibility helps firms earn trust and social capital during market downturns; their results are further supported by Jin et al. (2023). See also, for example, Cao, Duan, and Ibrahim (2023) and Li et al. (2023) for evidence from the Chinese stock markets.

Conversely, there are concerns that the inclusion of ESG criteria may reduce returns (see, e.g., Nagy, Kassam, and Lee, 2016) because the ESG tilts might underweight stocks with high risk-adjusted returns and overweight stocks with low risk-adjusted returns. The matter is serious as it is related to the investment fund manager’s fiduciary duty. However, such concern was lessened after the US Labor Department opined that ESG-related investment decisions made by pension plans do not violate the fiduciary duty of the sponsor and added that incorporating ESG ratings can create both social and financial benefits, according to Friede, Busch, and Bassen (2015). Nevertheless, there are questions raised as to whether the ESG rating is precise. For example, Berg, Kölbel, and Rigobon (2022) show that such ratings provided by the six prominent agencies are dispersed and mainly driven by divergences of scope and measurement methodology in addition to the assessor’s overall view of a firm. Besides, ESG rating might as well be a surrogate to known return predictors; hence, it does not present new valuable information to investors. For example, Melas, Nagy, and Kulkarni (2018) show that ESG ratings have a negative association with the value factor (see, e.g., Fama and French, 2015). In a similar vein, Authers (2020) argues that ESG investing could be a watered-down version of growth investing, with certain sectors such as technology and health care being overweight.

Our study examines whether the HSIESG is more resilient to market volatility than its parent, the HSI. However, unlike a best-in-class index—that is, an index or index portfolio constructed with a subset of top ESG-rated firms in a broad-based index such as the Standard & Poor 500—it is widely known that a weight-tilted narrow-based index is expected to be highly correlated with the parent index (see, e.g., Giese et al., 2019). Consequently, it is highly unlikely that the HSIESG can significantly outperform the parent HSI in any aspect. Therefore, the finding of a significant difference in the risk and return profiles between the ESG-infused HSIESG and the parent index would provide a strong testimony that the ESG-tilted weights have a material impact on the performance of the index portfolio and that the ESG-infused portfolio is more resilient to extreme rises in market volatility than the parent index due to a preference buffer.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

Although ESG investing is new to the Hong Kong equities market, the asset management industry has already begun to internalize the opportunity. The Hang Seng Indexes Co. Ltd., the provider of the HSI and various major Hong Kong stock market benchmark indexes, launched on May 14, 2019, the HSIESG. The HSIESG and its parent index are identical in all respects except that the HSIESG is constructed by shifting the index weights from firms with low ESG ratings to firms with high ESG ratings, where tilts are based on the ESG scores compiled by the HKQAA. The portfolio weight of a single stock has been capped at 8% for the parent index; the ceiling remains in effect for the tilt-adjusted weight of HSIESG. Weightings are not fully disclosed by HSI. There was no index exclusion from HSI during the period. If a stock is (not) in HSI, it is (not) in HSIESG - survivorship should not affect the comparison made in the study. Further, both indexes are subject to quarterly review.

The index provider has backdated the HSIESG to September 8, 2014. The overall sample covers 1,751 daily observations for the period September 8, 2014–October 31, 2021. The availability of the backdated sample allows a comparison of the findings between the prelaunch period (September 8, 2014–May 13, 2019; N = 1,148) and the postlaunch period (May 14, 2019–October 31, 2021; N = 603). However, it is expected that as the ESG score data were available also during the prelaunch period, the market at large should have included the information in their index portfolio, and it is expected that the key results from the two subperiods are similar according to Friede, Busch, and Bassen’s (2015) finding that the correlation between ESG and CFP is stable over time. Our paper uses daily data of the HSIESG, HSI, and VHSI retrieved from the Bloomberg terminal; the daily market factors for the Fama and Macbeth regression analysis are obtained from the Kenneth French Library. We use daily data to capture the time series dynamics of the index return in Hong Kong dollars. However, the main results (available upon request) are qualitatively the same using weekly and monthly returns.

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Performance Measurements and Comparisons

Conventional risk and return and other performance measures including the distributions of return, information ratio (IR), Sortino ratio, value at risk (VaR), expected shortfall (CVaR), and maximum drawdown are used to compare the risk and return between the ESG-infused and the parent indexes for the overall period and between the prelaunch and postlaunch subperiods. The information ratio is r/σ, where r is the mean daily return and σ is the standard deviation of daily returns. The Sortino ratio is r/σd, where σd is the standard deviation of negative returns (downside deviation). VaR (Value at Risk) measures the greatest possible losses over a specific time period at a particular percentile of return. Expected shortfall (also called conditional VaR) is the expected loss during the time period, conditional on a loss greater than the particular percentile of the loss distribution. Maximum drawdown calculates the downside risk as the difference between the peak and trough index values in percentage of the peak index value.

3.2.2. Tests for the Difference in Asymmetrical Volatility-Return Relationships between the HSIESG and HSI

The study first uses conventional multiple regression analysis to examine the volatility-return relationships for both indexes and across the two subperiods. All time-series regressions use the HAC Newey-West standard errors to account for both heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation in the error term. We use 10 lags in the Newey-West estimation and the results are similar using different lags. Next, we group the returns of the two indexes within each of the 10 bins defined by the deciles of the rate of volatility change. Decile 1 (the bottom volatility change bin) contains the index returns on days with the sharpest drop in market volatility, while decile 10 (the top volatility change bin) includes the index returns on days with the steepest rise in market volatility.

We use the HAC standard errors of Newey-West (1984) to test the statistical significance of the difference of mean returns. Further, we conduct a robustness check on the statistical significance of the mean returns and their differences using a bootstrapping method by resampling 10,000 times the returns to avoid the problem associated with the non-normality of the return distribution. For a return in a volatility change decile, from all the resampled means, we examine the observed distribution of the mean to see if the percentile range [0.5, 99.5] contains the value 0. If not, we define the mean of the return distribution to be 1% statistical significance. We report the results of the robustness tests in the

Appendix A.

3.2.3. Tests for Differential Exposure to Various Investment Factors

Fama and French’s (2015) five-factor models are used in this paper to assess the differential exposure to various market factors between the ESG weight-tilted HSIESG and the parent index. The results allow an examination of the relative performance between the ESG-infused index and the parent index. In their comparative study, Nagy, Kassam, and Lee (2016) show that an ESG tilt investment strategy that overweighs stocks with higher ESG ratings based on global MSCI data outperforms the benchmark. Finding similar results in Hong Kong would suggest that the ESG tilts have effectively incorporated and reflected the market’s relative preference for firms with high ESG scores.

We can provide more economic significance by adding suitable proxy variables for the ESG-individuals holdings of ESG stocks and norm-constrained institutional investors' holdings of ESG stocks in the pre-and post-period to test the main hypothesis that high-ranked ESG stocks' performance is resilient to market volatility. We reserve this issue for future research when data are available. 4. Findings and interpretations

Table 1 shows the summary statistics of daily returns on the ESG-weight tilted HSIESG, the parent HSI, and daily closing levels of and returns on the option implied volatility index derived from options written on the VHSI. The mean and standard deviation of daily returns of the two indexes are not statistically significantly different for the overall period and the two subperiods.

Table 2 shows the correlations among daily returns of the HSIESG and HSI, and the levels and returns of VHSI. All correlation coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level. The high return correlation (>99%) between the two indexes suggests that finding any significant differences in the risk and return profiles between the weight-tilted index and the parent index is highly unlikely. The negative and over 60% correlation between the two measures of volatility change and index returns are consistent with the widely documented negative volatility-return relationship in the equity markets. The negative volatility-return relationships have strengthened in the recent period for both indexes, and the change in correlations is qualitatively identical for both indexes. It is useful to mention here that the subperiod results do not reveal significantly different correlation patterns between the prelaunch and postlaunch periods.

Table 3 summarizes the key performance and risk metrics between the HSIESG and HSI. In general, the HSIESG has a higher return and a lower return standard deviation than those of the HSI, but the differences again are not statistically and economically significant. Specifically, the average daily returns are 0.0088% and 0.0084% for the HSIESG and HSI, respectively. The two subperiod results are qualitatively similar to those of the overall period. However, despite the insignificant differences in the arithmetic mean returns and return standard deviations between the two indexes, the holding period return of the HSIESG is substantially higher than its parent index by over 67% (i.e., 3.9657% vs. 2.369%), an important result that we will further explore in the subsequent sections.

Table 4 summarizes the test results on the negative and asymmetrical relationships between the index returns and the change in option implied market volatility. The regression results in Panel A show a highly significant negative relationship between index returns and the two measures in volatility changes. The slope coefficients for both measures of volatility change are negative at the 1% significance level, but the intercepts are mostly insignificant. Panel B shows that the intercept dummy and the slope coefficients are significantly negative at the 1% significance level concerning volatility change (ΔVHSI), an indication of the asymmetrical volatility-return relationship between the returns of the two indexes and the volatility change. Conversely, the slope coefficient has fully captured the volatility-return relationship for both indexes concerning volatility return (ΔlnVHSI). The regression test results further confirm the asymmetrical negative volatility-return relationship concerning the raw change in volatility. However, concerning the rate of volatility change, we find a highly significant negative volatility-return relationship in the slope coefficient but not in the intercept term. Furthermore, the subperiod results show no significant difference in the volatility-return relationship between the prelaunch and postlaunch periods.

Table 5 summarizes the mean daily returns for the HSIESG and HSI within each of the 10 bins defined by the deciles of the rate of volatility change. Decile 1 (the bottom volatility change bin) shows the mean index returns on days with the steepest drop in market volatility, while decile 10 (the top volatility change bin) shows the mean index returns on days with the sharpest rise in market volatility. Consistent with the regression results, the mean returns for both indexes are significantly positive in the bins with an average negative change in volatility and vice versa. The above findings are qualitatively similar for the two subperiods. We use the HAC standard errors of Newey-West (1984) to test the statistical significance of the results.

Table A1 in the

Appendix A report our robustness test via a bootstrapping method. The results from both tests are qualitatively identical. Most important, the asymmetrical response to the volatility of the ESG-infused index is significantly weaker than the parent index. For the overall period, the HSIESG has a lower mean return than the parent index (1.0496% vs. 1.1261%) for days with the highest drops in volatility. The opposite is true for days with the greatest spikes in volatility; where the HSIESG has a less negative mean return than the parent index (–1.6255% vs. –1.7235%).

Table 6 shows that the above-mentioned mean return differentials particularly for the top and bottom decile bins are statistically significant at the 1% level. Moreover, the results from the two subperiods are consistent with those found in the overall period. We also considered whether the market cap is the main driver of the differential asymmetrical risk-return relationship and the significant holding return gap between the two indexes. By examining a sample of snapshots (since the portfolio weights are changing over time) of the two sets of portfolio weights, we find that the tilted weights have generally migrated downward for the largest stocks. The reason is that because the weights of the largest stocks have already reached the cap rate in the parent index, the ESG tilts can shift their weights only downward. Hence, it is unclear whether the ESG performance is related to the market cap of the largest stocks. The table also shows the difference between the mean returns between the HSIESG and HSI (ΔlnHSIESG–ΔlnHSI) within each bin defined according to the volatility change decile. We test the differences using a t-test with the HAC standard errors of Newey-West (1984). The results show that the parent index HSI generally outperforms the ESG-infused HSIESG for days with the steepest volatility drop (within the volatility change decile 1 bin), while the opposite is true for days with the sharpest rise in volatility (within the volatility change decile 10 bin). The above findings are similar for the two subperiods.

Table A2 in the

Appendix A reports the robustness test results via a bootstrapping method. The results from both tests are qualitatively the same.

As noted in

Table 3, the less negative mean return of the ESG-infused index on days with the sharpst rise in volatility produces a substantially higher holding period return than the parent index (i.e., 3.9657% vs. 2.369%) despite the seemingly minor and statistically insignificant difference in the standard deviation of daily returns (i.e., 0.0115% vs. 0.0119%). Although the maximum drawdown of the ESG tilted index is slightly higher than the parent index by 31 basis points for the overall period, the 95% VaR and the CVaRs of the HSIESG for both confidence intervals are lower than those of the parent index. Moreover, the holding period return difference is mainly attributed to the differences in mean returns between the two indexes on days with the greatest drop and the steepest rise in market volatility (see the interpretation of results for

Table 5 and

Table 6).

To understand the large difference in the overall holding period return between the two indexes, we calculate the cumulative returns for days included in volatility change decile 1, decile 10, and the rest of the sample period. We find the following: (1) the cumulative return for days in decile 1 (the top 10% volatility change) is –380% and –399% for the HSIESG and HSI, respectively; (2) the cumulative return for days in decile 10 (the bottom 10% volatility change) is 343% and 355% for the HSIESG and HSI, respectively; and (3) the cumulative returns for all other days (deciles 2–9, both deciles included) are 41.74% and 46.01% for the HSIESG and HSI, respectively. This result leads to the conclusion that the HSIESG has a substantially higher holding period return than the parent index because the ESG-infused index have significantly less negative returns than the parent index during days with the highest volatility spikes.

Table 7 and

Table 8 summarize the test results on the sensitivity of the HSIESG and HSI returns to systematic risk measures via the Fama-French multifactor capital asset pricing model.

Table 7 summarizes the results using market factors of the developed international markets, while

Table 8 shows the results using the systematic risk factors of the Asia-Pacific markets excluding Japan. Both factors of SMB and HML for developed international markets (

Table 7) and Asia-Pacific markets ex Japan (

Table 8) are used. The analysis is extended to examine whether the official launch (vis-à-vis the prelaunch period) of the ESG tilted weights has a material impact on the performance of the HSIESG compared to the parent index. The results from the two subperiods are similar to those for the overall sample period. 4.

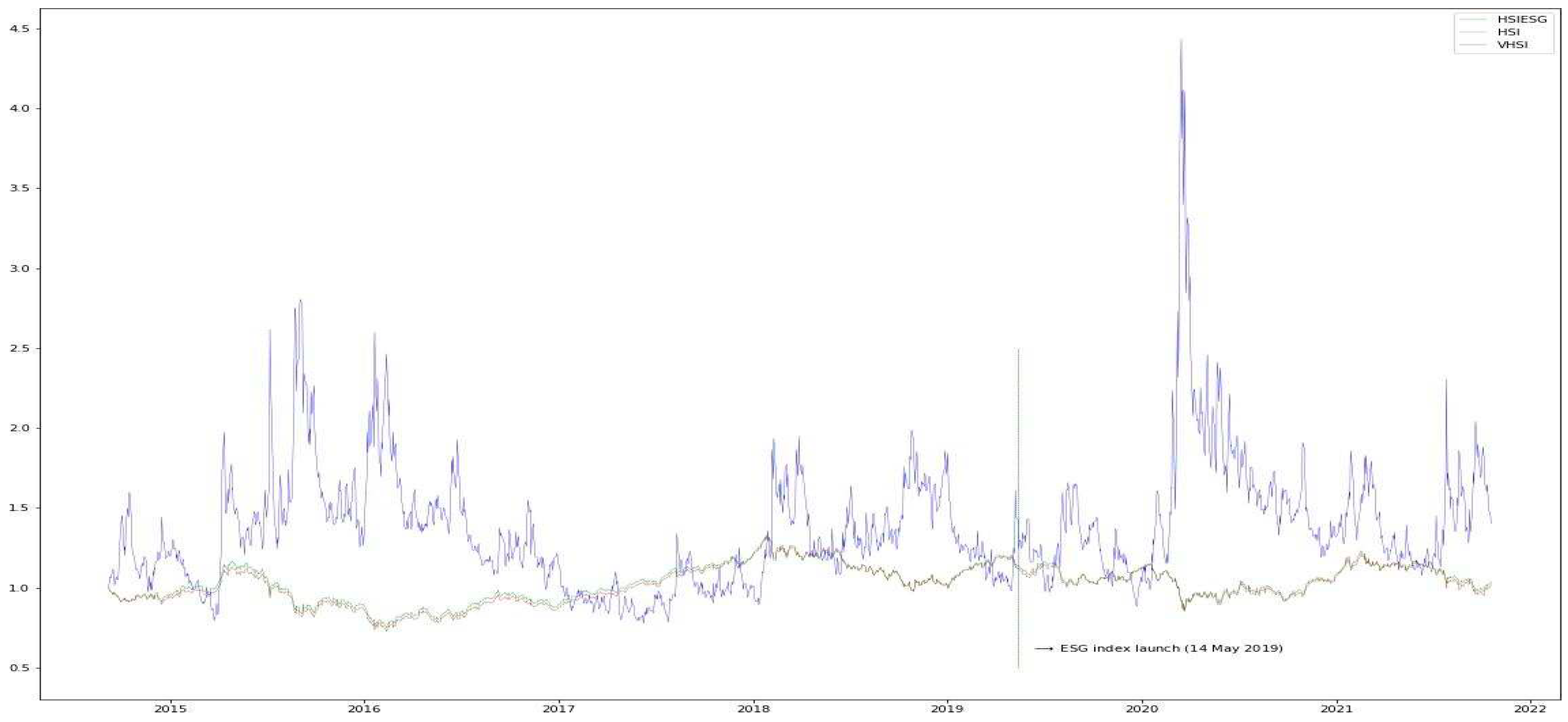

Figure 1.

Time series plot of the daily observations of the levels of Hang Seng Index options implied volatility index (VHSI) and the two stock indexes (HSIESG and HSI) for the period September 8, 2014–October 2021. The diagram shows the large variations in the perceived market volatility embedded in the Hang Seng Index options prices.

Figure 1.

Time series plot of the daily observations of the levels of Hang Seng Index options implied volatility index (VHSI) and the two stock indexes (HSIESG and HSI) for the period September 8, 2014–October 2021. The diagram shows the large variations in the perceived market volatility embedded in the Hang Seng Index options prices.

4. Conclusions

This study examines whether and to what extent the ESG tilted weights change the performance of the index portfolio relative to the parent index HSI. The paper first shows that the daily returns of the two indexes are very highly correlated, a preliminary result suggesting that the effect of ESG tilting is small. Consistent with the above conjecture, we find that the mean and standard deviation of returns are not significantly different between the two indexes.

Despite these similarities, the holding period return of the ESG-infused index is surprisingly higher than that of the parent index by over 67%. The unexpected result can be attributed to the difference in the strength of the asymmetrical volatility-return relationships between the two indexes for days with the highest and lowest volatility change. Specifically, the HSIESG has significantly less-negative returns than the parent index during days with the highest volatility spikes, a result attributable to the investors’ preference to hold on to stocks with high ESG ratings during volatile periods. This finding explains why the HSIESG has a substantially higher holding period return than the HSI and supports the proposition that stocks with high ESG ratings are less susceptible to trading pressures triggered by volatility-induced turnovers. Conversely, the results support our conjecture that ESG ratings are priced in the market, making stocks with high ESG ratings less valuable for speculation, while the preference for such stocks buffers against panic selling when the market is adversely affected by a large jump in the fear factor. The overall results indicate that stocks with high ESG ratings can be a good hedge against downside risks and financial crises.

Although the results of this study are primarily based on the newly introduced HSIESG, it sheds light on the potential economic benefits of incorporating ESG information into the construction of stock market indexes. ESG indexes may support the development of relevant index products such as ESG-linked equity ETFs, derivatives, other exchange-traded products, and mutual funds. Currently, there are 36 and 34 investment products linked to the parent indexes HSI and Hang Seng China Enterprises Index, respectively. These products include local ETFs, ETFs listed around the world, leveraged and inverse products in Hong Kong, classification fund and listed open-ended fund in China, mandatory provident fund in Hong Kong, and index funds worldwide. Growth in such markets may help promote Hong Kong as a major sustainability and green financial hub and reinforce its status as a global financial center.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The mean returns of the HSIESG (ΔlnHSIESG) and HSI (ΔlnHSI) for each decile of volatility return (ΔlnVHSI) classification for the overall period and the prelaunch and postlaunch subperiods: A bootstraping approach.

Table A1.

The mean returns of the HSIESG (ΔlnHSIESG) and HSI (ΔlnHSI) for each decile of volatility return (ΔlnVHSI) classification for the overall period and the prelaunch and postlaunch subperiods: A bootstraping approach.

| |

Overall |

Prelaunch |

Postlaunch |

| |

ΔlnVHSI |

ΔlnHSIESG |

ΔlnHSI |

ΔlnVHSI |

ΔlnHSIESG |

ΔlnHSI |

ΔlnVHSI |

ΔlnHSIESG |

ΔlnHSI |

| Decile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

–9.0953 |

1.0496*** |

1.1261*** |

–8.5521 |

0.9139*** |

0.9788*** |

–10.0522 |

1.3110*** |

1.4060*** |

| 2 |

–4.8753 |

0.6018*** |

0.6380*** |

–4.7405 |

0.5751*** |

0.5965*** |

–5.1077 |

0.6366*** |

0.6991*** |

| 3 |

–3.3732 |

0.4504*** |

0.4737*** |

–3.3077 |

0.4153*** |

0.4319*** |

–3.4804 |

0.5012*** |

0.5462*** |

| 4 |

–2.3367 |

0.3418*** |

0.3534*** |

–2.2652 |

0.2854*** |

0.2977*** |

–2.4734 |

0.4751*** |

0.4931*** |

| 5 |

–1.2689 |

0.1447*** |

0.1519 |

–1.1902 |

0.2009*** |

0.2002*** |

–1.4111 |

0.0582 |

0.0628 |

| 6 |

–0.1699 |

0.0390 |

0.0515 |

–0.0936 |

0.0610 |

0.0663 |

–0.3035 |

0.0148 |

0.0408 |

| 7 |

1.0704 |

–0.0478 |

–0.0637 |

1.1353 |

–0.0483 |

–0.0587 |

0.9268 |

–0.0775 |

–0.1038 |

| 8 |

2.6172 |

–0.2573*** |

–0.2899*** |

2.6346 |

–0.1870 |

–0.2040 |

2.5615 |

–0.3746 |

–0.4274*** |

| 9 |

4.9207 |

–0.6085*** |

–0.6334*** |

4.7841 |

–0.5562*** |

–0.5867*** |

5.2033 |

–0.8251*** |

–0.8652*** |

| 10 |

12.7039 |

–1.6255*** |

–1.7235*** |

11.9064 |

–1.4779*** |

–1.5480*** |

14.0373 |

–1.7779*** |

–1.9015*** |

Table A2.

The differential mean returns between the HSIESG and HSI (ΔlnHSIESG – ΔlnHSI) for each decile of volatility return classification: A bootstraping approach.

Table A2.

The differential mean returns between the HSIESG and HSI (ΔlnHSIESG – ΔlnHSI) for each decile of volatility return classification: A bootstraping approach.

| |

|

Overall |

|

Prelaunch |

Postlaunch |

|

| |

ΔlnVHSI |

ΔlnHSIESG – ΔlnHSI |

ΔlnVHSI |

ΔlnHSIESG – ΔlnHSI |

ΔlnVHSI |

ΔlnHSIESG – ΔlnHSI |

| Decile |

|---|

| 1 |

–9.0953 |

–0.0765*** |

–8.5521 |

–0.0649*** |

–10.0522 |

–0.095*** |

| 2 |

–4.8753 |

–0.0362*** |

–4.7405 |

–0.0214 |

–5.1077 |

–0.0625 |

| 3 |

–3.3732 |

–0.0233 |

–3.3077 |

–0.0166 |

–3.4804 |

–0.045 |

| 4 |

–2.3367 |

–0.0116 |

–2.2652 |

–0.0123 |

–2.4734 |

–0.018 |

| 5 |

–1.2689 |

–0.0072 |

–1.1902 |

0.0007 |

–1.4111 |

–0.0046 |

| 6 |

–0.1699 |

–0.0125 |

–0.0936 |

–0.0053 |

–0.3035 |

–0.026 |

| 7 |

1.0704 |

0.0159 |

1.1353 |

0.0104 |

0.9268 |

0.0263 |

| 8 |

2.6172 |

0.0326*** |

2.6346 |

0.017 |

2.5615 |

0.0528 |

| 9 |

4.9207 |

0.0249*** |

4.7841 |

0.0305*** |

5.2033 |

0.0401 |

| 10 |

12.7039 |

0.098*** |

11.9064 |

0.0701*** |

14.0373 |

0.1236*** |

References

- Authers, J., May 2020. ESG Investing Is Having a Good Crisis. It’s Also Killing Jobs, Bloomberg Markets.

- Berg, F. , Kölbel J., and Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissoondoyal-Bheenick, E. , Brooks, R., and Do, H. X. ESG and Firm Performance: The Role of Size and Media Channels. Econ. Model. 2023, 121, 106203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown Brothers Harriman, April 2019. 2019 Global ETF Investor Survey: Greater China Results Supplement.

- Cao, M. , Duan, K., and Ibrahim, H. Local Government Debt and Its Impact on Corporate Underinvestment and ESG Performance: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Asset & Wealth Management, December 2015. ESG & Corporate Financial Performance: Mapping the Global Landscape.

- Dunn, J. , Fitzgibbons, S., and Pomorski, L. Assessing Risk through Environmental, Social and Governance Exposures. J. Invest. Manag. 2017, 16, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R.G. , Ioannou, I., and Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, Sadok, Guedhami, O., Kwok, C.C.Y., and Mishra, D.R. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect the Cost of Capital? Journal of Banking and Finance 2011, 35, 2388–2406. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F. , and French K.R. A Five-Factor Asset Pricing Model. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 116, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A. , Fooladi, I., and Tehranian, H. Valuation Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 10, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G. , Busch, T., and Bassen, A. ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More than 2000 Empirical Studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G. , Lee, G.L., Melas, D., Nagy, Z., and Nishikawa, L. Foundations of ESG Investing: How ESG Affects Equity Valuation, Risk, and Performance. J. Portf. Manag. 2019, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G. , Lee, G.L., Melas, D., Nagy, Z., and Nishikawa, L. Performance and Risk Analysis of Index-Based ESG Portfolios. J. Index Invest. 2019, 9, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. , Merrill C.B., and Hansen, J.M. The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder Value: An Empirical Test of the Risk Management Hypothesis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A. , Tharyan, R., and Whittaker, J. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Value: Disaggregating the Effects on Cash Flow, Risk and Growth. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 633–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H. , and Kacperczyk, M. The Price of Sin: The Effects of Social Norms on Markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, June 18, 2020. HKEX to Launch New Sustainable and Green Exchange. News Release.

- International Monetary Fund, October 2019. Global Financial Stability Report: Lower for Longer.

- Jin, Y. , Liu, Q., Tse, Y., and Zheng, K. Hedging COVID-19 Risk with ESG Disclosure. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 88, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P. Corporate Goodness and Shareholder Wealth. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. , Huang, L., Zhang, J., Huang, Z., and Fang, L. Can ESG Performance Alleviate the Constraints of Green Financing for Chinese Enterprises: Evidence from China’s A-Share Manufacturing Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V. , Servaes, H., and Tamayo, A. Social Capital, Trust, and Firm Performance: The Value of Corporate Social Responsibility during the Financial Crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melas, D., Nagy, Z., and Kulkarni, P. Factor Investing and ESG Integration, Factor Investing: From Traditional to Alternative Risk Premia, ISTE Press–Elsevier 2018, 389–413.

- Moody’s, February 2020. Beyond Passive, ESG Investing Is the Next Growth Frontier for Asset Managers, Moody’s Investor Service.

- Nagy, Z. , Kassam, A., and Lee, L.E. Can ESG Add Alpha? An Analysis of ESG Tilt and Momentum Strategies. J. Invest. 2016, 25, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newey, W.K. , and West, K.D. A Simple, Positive Semi-Definite Heteroskedasticity and Autocorrelation Consistent Covariance Matrix. Econometrica 1984, 55, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, I. , Brooks, C., and Pavelin, S. The Impact of Corporate Social Performance on Financial Risk and Utility: A Longitudinal Analysis. Financ. Manag. 2012, 41, 483–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulino, S.C. , Ciaburri, M., Magnanelli, B.S., and Nasta, L. Does ESG Disclosure Influence Firm Performance? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K., and Wu, J., September 2019. How Is ESG Affecting the Investment Landscape?

- J.P. Morgan Asset Management on the Minds of Investors.

- Wasiuzzaman, S. , Ibrahim, S.A., and Kawi, F. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure and Firm Performance: Does National Culture Matter? Meditari Accoutancy Research, ahead-of-print. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., and Juvyns, V., May 2020. COVID-19 Shows ESG Matters More than Ever. J.P. Morgan Asset Management on the Minds of Investors.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).