INTRODUCTION

Among the species of small cetaceans reported for the coastal waters of northern Chile (Iriarte, 2008; Iriarte et al., 2011; Jefferson et al., 1993; Cárdenas el al., 1986; Van Waerebeek and Guerra-Correa, 1987,1988; Auger, 2018; Guerra-Correa et al., 1987; Aguayo-Lobo et al., 1998; Culik and Würtz, 2004; Bastidas et al., 2007; García-Cegarra et al., 2021), several of them stand out negatively for their high frequency of strandings. The Burmeister’s porpoise Phocoena spinipinnis Burmeister, 1865 being the species with the highest incidence, as indicated by the official stranding records from 2009 to 2021 (Sernapesca, 2023).

Phocoena spinipinnis, a species of the family Phocoenidae, inhabits mainly coastal waters, in the eastern South Pacific, from Paita, northern Peru (5°S) south continuously along the coasts of Chile to Tierra del Fuego in the southern cone of South America. Its Atlantic distribution covers the coasts of Argentina and Uruguay, reaching north to the Brazilian coast to approximately 28°S (Reyes and Van Waerebeek, 1995; Molina-Schiller et al., 2005; Reyes, 2018). Thus, it reveals preferences for the cool waters of the Humboldt Current in the SE Pacific and the Falklands Current in the SW Atlantic (Rosa et al., 2005; Reeves et al., 2002). It has recently been reported from waters adjacent to the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) (Weir and Rutherford, 2019).

The name P. spinipinnis is due to rows of small dermal protuberances (‘spines’) on the anterior edge of the dorsal fin. This small porpoise presents a dark, rather cryptic coloration that blends in with the sea, a backward-leaning dorsal fin, and when breathing it shows very little body emerging above water, all of which promotes its low detectability. In addition, it is encountered typically dispersed, most frequently as pairs or solitary individuals and rarely forms large herds (Van Waerebeek et al., 2002; Reyes, 2018; Clay et al., 2018).

Their nearshore distribution ranges from ca. the 60 m isobath to shallow nearshore waters including some estuarine areas. Their feeding habits of preying on mainly small fish (Reyes and Van Waerebeek, 1995; García-Godos et al., 2007) expose them to incidental captures in small-scale coastal fisheries and perhaps other human activities at sea, which explains the high frequency of carcass stranding records and the species’ delicate state of conservation (Reyes, 2018; Clay et al., 2018; Van Waerebeek et al., 2018; Ortiz-Alvarez et al., 2022).

In northern Chile, evidence was found that the Burmeister’s porpoise has been exploited for human consumption (Van Waerebeek and Guerra-Correa, 1987). In coastal areas such as Antofagasta and Chañaral, the occurrence of incidental takes in drift and set gillnets was verified in past decades (Van Waerebeek and Guerra-Correa, 1987). The analysis of carcasses carried out in the present study added evidence of apparent mortality due to attacks by other cetaceans. These facts, the precarious information on the species and its conservation status, motivated the authors to review the photographic records, data and materials deposited at the Regional Center for Environmental Studies and Education of the University of Antofagasta (Centro Regional de Estudios y Educación Ambiental, CREA-UA), in order to evaluate the hypothesis of an additional cause of mortality of P. spinipinnis to those previously known.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

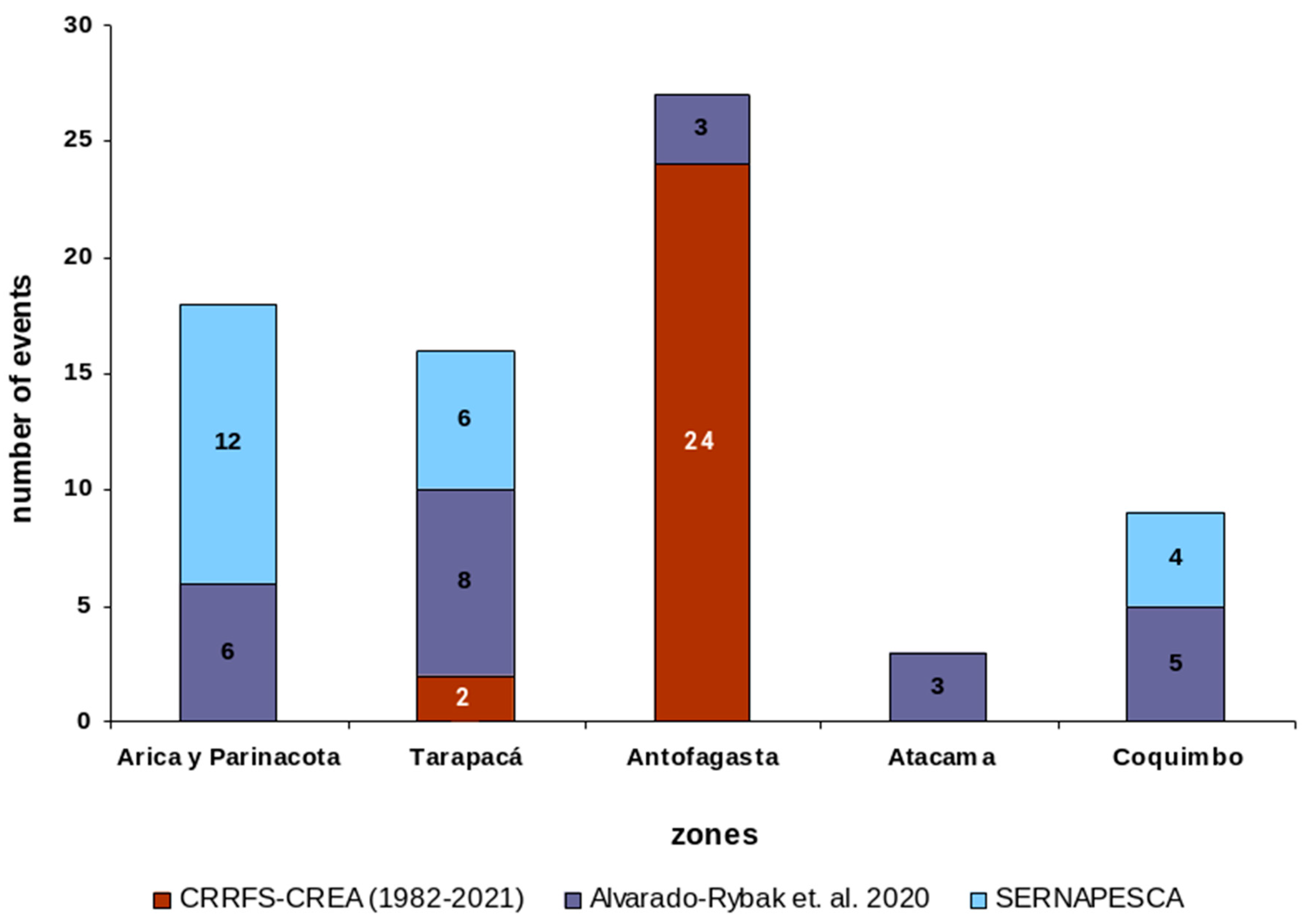

The research on stranding cases and causes of mortality of P. spinipinnis in Chile was limited to the geographical area between Arica (18°29'S) and Coquimbo (29°57'S), further referred to as 'northern Chile', approximately 1,280 km of coastline and adjacent sea. For this purpose, we first compiled official information provided by the National Fisheries Service, Servicio Nacional de Pesca (SERNAPESCA), an institution that presents systematic, documented data since 2009, concluding our review with the latest stranding data, recorded in the study area in September 2021. Subsequently, we reviewed documentation published in journals and reports with professional and institutional support, especially a temporal-spatial analysis of strandings in Chile (Alvarado-Rybak et al., 2020). The cases were complemented with information from the Centro de Rescate y Rehabilitación de Fauna Silvestre (CRRFS-UA) or Wildlife Rescue and Rehabilitation Center of the University of Antofagasta, a unit dependent on CREA-UA, which coordinates with SERNAPESCA. The center receives specimens of stranded small cetaceans for registration, sampling and the determination of causes of death, a task that is generally carried out in coordination with professionals from SERNAPESCA Regional Directorate. The CREA-UA database incorporates marine fauna records since 1985, in continuation of the research work carried out by the former Oceanological Research Institute (Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas) of the University of Antofagasta (e.g. Guerra-Correa et al., 1987; Van Waerebeek and Guerra-Correa, 1987).

Traumatic injuries, evidence of aggression produced by other cetaceans were evaluated by necropsy and/or photographic material of specimens in the historical record held by CREA-UA. The existence of tooth rake type injuries and other marks or scars on the skin, left by apparent bites from other cetaceans, was investigated. Also, when possible, the condition of bones and internal organs of the affected specimens was checked for fractures, internal hemorrhage and other blunt or penetrating traumas. The body was divided externally by anatomo-topographical sections: a) caudal fin (flukes) section; b) caudal peduncle section; c) genito-abdominal section; d) mid-body section (including pectoral and dorsal fins and thoracic area) and e) the head. In each section, tooth rakes were selected that had a straight trajectory within which measurements of distances between them, the inter-rake distance, (IRD) were made.

In order to determine the species that could have produced the observed rake wounds, measurements of IRD between marks were compared with distances between teeth in dolphin skulls curated at the CREA-UA collection. Reference values for other species, unavailable in the collection, were obtained from reports published by various authors, which complemented the comparisons. Due to a lack of skulls with intact teeth, mean interdental distance for false killer whale Pseudorca crassidens was determined from mandibular tooth row length and number of tooth alveoli. Included were two specimens of the Museo de Delfines, Pucusana (Lima), one adult (CEPEC-003) and another subadult (JCR-744), plus an adult skull graphically well-documented in Odell and McClune (1999).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In northern Chile there are frequent sightings and records of strandings of several small cetaceans, the more common being:

Tursiops truncatus, Lagenorhynchus obscurus,

Delphinus spp.,

Phocoena spinipinnis, Grampus griseus,

Globicephala melas, G. macrorhynchus, Pseudorca crassidens,

Lissodelphis peronii and

Kogia spp. (e.g. Guerra-Correa

et al., 1987; García-Cegarra et al., 2021). Other species, like

Ziphius cavirostris, are far less frequent or correspond to larger species and were not considered in the comparison. For the 10 species (or genera) of small cetaceans in the SERNAPESCA database (n=54 cases) it is estimated that of the total stranding events

1 in northern Chile between 2009 and 2021, the frequency of

P. spinipinnis corresponds to 48.1 % of the total, followed by

L. obscurus (16.7 %) and

Delphinus spp. (11.1 %).

Table 1 shows the significant differences (Χ

2=28.6034; DF=9; p=7.558x10

-4) of stranding events among species. A similar analysis (

Table 1) performed with selected data (1968 - 2020) from Alvarado-Rybak et al. (2020), shows

P. spinipinnis with 35 % of stranding events, followed by

L. obscurus (14.2 %) and

G. griseus (9.4 %), also evidencing significant differences between species (Χ

2=30.8837; DF=9; p=3.099x10

-4).

This same trend is reflected in the count of stranding events of all cetaceans nation-wide, by the same authors (Alvarado-Rybak et al., 2020), where P. spinipinnis recorded the highest number of stranding events (n=66), followed by L. obscurus (n=21). These data reaffirm that the Burmeister’s porpoise is the cetacean species with the highest frequency of mortality events, results that may imply significant losses of population components. This situation is reminiscent to conditions found in southern and south-central Peru where P. spinipinnis is also the predominant cetacean species encountered dead on the beach, both calculated as stranding events and in absolute numbers (Pizarro-Neyra, 2010; Van Waerebeek et al., 2018; Ortiz-Alvarez et al., 2022).

It has been documented that part of the losses have been caused by interactions with fisheries (Molina-Schiller et al., 2005) and, possibly, other human activities at sea, compounded by their markedly coastal distribution (Van Waerebeek and Guerra-Correa, 1987, Van Waerebeek et al., 2002, Guerra-Correa et al., 1987, Reeves et al., 2002; Clay et al., 2018). Despite this dispersed condition, stranding events are not massive (e.g., 70 individuals stranded in 66 events or 1.06 ind./event). However, when comparing the absolute frequency of strandings among smaller cetaceans, P. spinipinnis is placed fourth in the ranking, surpassed by three species that have gregarious habits and their stranding events have generally been massive. Such is the case of Globicephala melas and Pseudorca crassidens, with a total of 315 and 337 individuals stranded, respectively, throughout the entire Chilean coast between 1968 and 2020 (mean= 24.2 ind/event and 33.7 ind/event, respectively) and also slightly surpassed by Grampus griseus with 76 individuals and an average of 5 ind./event (Alvarado-Rybak et al., 2020).

The pooled

P. spinipinnis strandings for northern Chile (n=73) recorded by SERNAPESCA, Alvarado-Rybak

et al. (2020) and those of the present study, arranged latitudinally, adjusted by origin (no repetition between sources of information), are illustrated in

Figure 1. Antofagasta with 27 events accounted by far for the largest proportion (37.0%), Arica/Parinacota and Tarapacá recorded 18 and 16 events (24.7 % and 21.9 %) respectively, while Atacama and Coquimbo recorded three (4.1 %) and nine events (12.3 %), respectively.

The information generated up to this point shows the vulnerability of Phocoena spinipinnis in Chilean waters, being the smallest cetacean species with the highest incidence of mortality events and the fourth in absolute number of individuals. The data also indicate that this higher incidence occurs towards the northern end of the study area, unless it can be argued that there is reduced surveillance coverage in some coastal segments with a lack of professionals to support this work. However, it seems to be clear that, even so, the species presents a high frequency of strandings that may involve both natural and anthropogenic agents of mortality, a situation of concern and thus a motivation to devote greater research efforts.

Several causes of death have been mentioned in official reports, in the scientific literature, in the compilation of information received directly from artisanal and industrial fishermen or in necropsy reports (e.g. Guerra-Correa et al., 1987; Van Waerebeek and Guerra-Correa, 1987; Auger, 2018; García-Cegarra et al., 2021). Burmeister’s porpoises suffer incidental death ver, in fishing gear such as entanglement in various types of drift and set gillnets, but also entrapment in purse-seine nets (red bolichera) set for small-schooling fishes such as Peruvian anchovy (Engraulis ringens). This includes in some cases entanglement in net folds and mechanical squeezing that produces accidental passage through the power block which hauls the purse-seine net in semi and industrial fishing vessels (bolicheras). Also, entanglement with croaker fishing lines, impact of use of explosives and other incidental death events have been recorded. Occasionally, intentional targeting for human consumption or to exercise the technique of albacore harpooning from the bowsprit (tangón) of this type of vessel, has also been mentioned (own data CGC). However among the set of threats that are part of the anecdotal record of coastal and epipelagic fishing, there was no record of death in P. spinipinnis from attacks by other cetaceans.

Among the records analyzed by the CRRFS-CREA team, evidence of mortality from a threat that had not been documented for Burmeister’s porpoise was detected in two stranded specimens. One of these was found by CGC during coastal explorations and the other was passed on to the University of Antofagasta by the Taltal SERNAPESCA office.

The first specimen, an adult male Burmeister’s porpoise carcass (record 27409) found at the Playa Grande of Mejillones sector (23° 0’ S; 70°19 W) on 27 April 2009 (

Table 2). The carcass, with condition status 3-4, presented characteristics of ca. one week postmortem (

Figure 2), evidence of scavenging by vultures and partial detachment of epidermis. Tooth rake-like marks were detected on the lateral rostrum, dorsal fin and flukes. The specimen was examined

in situ but not collected.

The second specimen (CRRFS 3120b) came from Balneario Tierra del Moro beach (25°22’ S; 70°27' W), about 4.5 km north of Taltal city, and was transferred to the University of Antofagasta by SERNAPESCA personnel on 20 May 2019. It was a male specimen, still fresh (

Figure 3), which allowed the necropsy to be performed with the participation of various CRRFS professionals. Some morphometrics are given in

Table 2. The complete skeleton now forms part of the osteological collection of CREA.

Both animals were adult males, with parallel, linear injuries on their skin, diagnosed as evident tooth rake marks.

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5, and

Figure 6 illustrate the condition of the Taltal specimen and the injuries on the body. This specimen, with the freshest marks, was used to measure the inter-tooth rake distance (IRD)(

Table 3). The IRD on the caudal peduncle and center of the body were slightly greater than the IRD on the tail, which could be explained by a more paraxial traction of the teeth of the aggressor cetacean, or because it corresponds to a smaller individual attacking the fin and flukes. However, we suggest that on the caudal peduncle and genito-abdominal section, wider bite marks may indicate more lateral traction (Figures 7 and 8), more accurately reflecting the actual distance between teeth of the cetacean aggressor.

Barnett et al. (2015) reports violent interactions by Tursiops truncatus on several other small cetacean species, such as juveniles and adults of Delphinus delphis, a juvenile pilot whale Globicephala sp., adult striped dolphin Stenella coeruleoalba and a juvenile Grampus griseus. They provide data on inter-mark measurements of bites, which showed a mean of 11.3 mm (SD=1.28). Ross and Wilson (1996) report on mortality of harbour porpoise Phocoena phocoena caused by T. truncatus attacks, having directly observed some of these. They compared the marks with interdental distance (IDD) data from several cetacean species, two of which are important for comparisons in the present study. Ross and Wilson (1996) indicate that T. truncatus has an average IDD of 11.6 mm (95% CI= 10.97 - 12.32), while Grampus griseus has an average IDD of 16.48 mm (95% CI= 15.28 - 17.67). With data on IDD and IRD distances and observational records of attacks, they conclude that the aggressor species must be T. truncatus.

The data obtained from the osteological collection of the CRRFS-CREA allowed us to compare the IDD of

L. obscurus,

T. truncatus and

G. melas (

Table 4).

Orcinus orca was readily discarded because its IDD values ranged from 28.6 to 35.1 mm (Ross and Wilson, 1996) and far exceeded the IRD measured on the Burmeister’s porpoises.

Pseudorca crassidens and

Globicephala melas were also discarded with IDD values, respectively, mean 26.6 mm (SD 2.8; range 23.5–29.0) and 16.14 mm (SD 2.2), based on our own measurements and Odell and McClune (1999).

Globicephala macrorhynchus has fewer teeth and even a higher IDD than its congener

G. melas, but precise data need to be collected.

The combined evidence of IRD and IDD measurements, and the well-documented confirmed antagonistic behaviour in the literature, it is reasonable to assign the authorship of the aggression against P. spinipinnis to T. truncatus. According to the observations of one of the authors (CGC), this species seems to have increased its presence in the Antofagasta area during the last decade.

Although an episode of T. truncatus aggression has not been witnessed in Chile, the necropsy records of the porpoise specimen from Taltal show that it not only suffered bites, but also high-impact blows to the body, potentially caused by the caudal peduncle/flukes or rostrum leading to extensive blunt trauma. Subdermal hematomas were present laterally on the thoracic area, evidenced by diffuse bleeding between the hypodermic musculature and the ribs. Inside the thoracic cage, severe traumatic lesions were evidenced in the right lung lobes with rupture of pleura and extrusion of lung parenchyma (Figure 9). Abundant foam was present in the trachea and general contusion affected the internal walls of the thorax.

Cotter et al. (2012) provides an observational account of antagonistic behaviour by T. truncatus against P. phocoena in Monterey Bay, California, describing four forms of aggression, three of which could explain the internal lesions detected in the necropsy of the Chilean P. spinipinnis. The first they call ‘sandwiching’, which consists of hitting the targeted animal hard between two dolphins with blows on its flanks that may throw it out of balance and may cause fractured ribs. The second, ‘launching’ of the porpoise out of the water by blows with the rostrum or tail, which is repeated sequentially by several dolphins. The third one, called ‘ramming’, consists of high-speed movements that end up hitting the victim with high impact blows by the dolphins' body or head, a repetitive action sometimes performed by several dolphins simultaneously. Finally, they describe ‘drowning’, which consists of taking or pushing the porpoise, positioning it so that the back part of its body is out of the water and its head is submerged, impeding it to breathe.

Although aggression by T. truncatus against small cetaceans have been reported by several authors (Patterson et al., 1998; Ross and Wilson, 1996; Barnett et al., 2009), the information by Cotter et al. (2012) is highly relevant because they are certain that all violent acts were carried out by male individuals, which enriches the discussion regarding the potential reasons for the aggressive behavior. Several hypotheses have been proposed, some of which have been discarded and there seems to be no agreement on a particular explanation. Among the aspects discussed are: (a) competition for prey or food interference; (b) interspecific territoriality; (c) playful practices to improve infanticidal skills; (d) playful practices to improve fighting skills between male dolphins; (e) sexual frustration; (f) aberrant behavior, which has been rejected because to date enough events have been documented to affirm that it corresponds to a behavior typical of T. truncatus.

The present report is the first that documents lethal interspecific aggressive behavior against Phocoena spinipinnis which is not of predatory nature and the first evidence of such a phenomenon in cetaceans from Chilean waters. It underscores the scarce information available on the biology and ecology of this phocoenid in Chile and elsewhere. Expanding our knowledge base with more focussed, systematic, field research would be of great use to help formulate effective management measures, and to ensure the Burmeister’s porpoise long-term conservation through reduction of fisheries interactions and other anthropogenic threats. In Chile it is classified as Data Deficient (D.S. N°06-2017), so its real conservation status is unknown.