1. Introduction

“Happiness depends upon ourselves.”—Aristotle

Happiness has been a pursuit of mankind since ancient times. Since the 1960s, numerous disciplines have conducted research related to “happiness”. Among them, psychologists, starting from their own disciplinary characteristics, focused on how to pave the way for people to achieve happiness and the impact of a sense of happiness on individuals’ psychology and behavior (Steptoe, 2019).

Although there has been considerable research into the sense of happiness (Veenhoven, 2012), numerous issues still permeated happiness studies. Of these, cross-cultural consistency was paramount. With the cultural revolution in psychology took place in the 1980s, researchers began to notice that the same psychological terminology seems to harbor different connotations in different cultures. As early as the beginning of the 21st century, researchers identified differences in the concept of happiness in Chinese and American cultures from interviews with college students in Taiwan and the United States (Lu & Gilmour, 2004). Not only did the word “happiness” differ in its written form in different cultures, but also its connotations varyed, among which the happiness in Chinese culture was particularly worth noting. Researchers found that in 30 cultures, 24 countries associate happiness with “luck”, and Chinese culture’s interpretation of happiness had its own characteristics (Oishi et al., 2013). Therefore, exploring the content of happiness in Chinese culture was crucial not only for enhancing cross-cultural understanding and facilitating cross-cultural communication and exchanges, but also for enriching happiness theory and providing realistic significance for the development of cultural products.

1.1. What Is Happiness

Happiness or subjective well-being(SWB) is a positive inner experience, as the highest good and the ultimate motivator for all human behaviors has attracted ever increasing attention from psychologists over the past decades (Diener, 1984; Veenhoven, 1993). In numerous cross-cultural studies, people in Eastern societies, such as China, tended to have lower scores for happiness. Many researchers attributed this to their traditional culture, which was rooted in collectivism, believing that individuals within cultures favoring individualism were expected to experience higher levels of happiness (Diener et al., 2003).

However, the World Happiness Report (Helliwell et al., 2023) pointed out that subjective well-being should be measured based on a tripartite framework: Life evaluations, positive emotions, and negative emotions. The connotation of happiness for Chinese individuals diverged from Western perspectives--happiness for Eastern people was considered a dialectical balance. Blessings and misfortunes were interdependent and could transform into each other, suggesting that instead of excessively pursuing joy, one should seek inner peace and harmony with the outside world (Lu, 1998). For the Chinese, happiness extended beyond hedonistic sensory pleasure. It was instead achieved through harmonious co-existence with others, society, and nature, leading to a state of inner tranquility (Qiong, 2005). Consequently, the Chinese concept of happiness encompassed not only an individual’s satisfaction with their life but also comprehensive evaluations of relationships, family, and society to reach a state of harmony and happiness.

Therefore, to probe into happiness among Chinese individuals, one must employed multiple measurement tools to evaluate it from various angles and dimensions. One of the most classic tools for measuring happiness was the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS, Diener et al., 1985), which assessed general life satisfaction. Afterwards, Seligman (2018) defined happiness from five angles: Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. Subsequently, the PERMA-Profiler was developed to measure PERMA (Butler & Kern, 2016). This questionnaire, which has a high degree of reliability and validity, along with a standardized Chinese version, was also used in this study. Assessing happiness should also incorporated the measurement of individual emotions. Therefore, we also adopted the PANAS scale (Watson et al., 1988; Huang et al., 2003). Assessing happiness should also incorporated the measurement of individual emotions. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the happiness of Chinese individuals encompassed not only personal happiness but also the evaluation of social relationships. In order to provide a more comprehensive portrayal of the happiness experience within Chinese culture, this study also incorporated the relationship dimension from the Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Xing & Huang, 2004), as well as the Social Well-Being Scale, an extension of the “Psychological Well-Being” model (Keyes, 1998; Liu & Huang, 2016).

1.2. The Happiness Circle in Chinese

Previous research found that individualism-collectivism may be one of the cultural dimensions affecting happiness, but this effect may be due to only measuring one aspect of individual happiness during cross-cultural comparison. Yang (2018) posited that, in addition to their own happiness, Chinese people’s concept of happiness also included concern for the happiness of others. In other words, for Chinese people, being good on one’s own did not constitute happiness. Having good relationships with others and seeing their close ones happy to form Chinese people’s view of happiness. The main ideological source of Chinese culture came from Confucian thinking, advocating not only the pursuit of personal happiness but also the happiness of all people. It required individuals to have the mindset of benefiting everyone beyond just benefiting oneself (Yip et al., 2021). Similarly, Buddhism, which occupies an important position in Chinese culture, also believed that while a person strives to become a Buddha, they should also save all sentient beings from suffering, as true liberation was achieved among the multitude. Moreover, Buddhism also insisted that even after one has attained enlightenment, one should make every effort to help others reach a state of bliss(Guang, 2013).

People in collectivist cultures were more willing to sacrifice their own desires and conform to the will of the group (Markus, 1996). In such cultures, there was a stronger link between individual’s perception of cultural norms and life satisfaction. Compared with Westerners, Chinese people had six unique sources of happiness: harmonious relationships with friends and family, praise of others, better life conditions than others, acceptance of fate, material satisfaction and work achievements (Lu & Shih, 1997). The first three items were closely related to others (or society). Subsequent research had validated the causal influence of social support and social expectations on happiness(Chan & Lee, 2006). In summary, others not only provided the reference standard for whether an individual judges themselves to be happy, but in Chinese culture, the happiness of others and the individual were interdependent. That was, in helping others to achieve happiness, an individual also realized their own happiness. In other words, under the influence of traditional Chinese culture value, an individual’s happiness was influenced by their relationships with others.

Therefore, the Chinese concept of happiness should encompass individual happiness, family happiness, and societal happiness, with potentially varying levels of importance for each aspect of happiness. The degree to which happiness was influenced by interpersonal relationships is hierarchical. Chinese society exhibited a hierarchical social pattern(Liu et al., 2016; Fei, 1998). Ascribed relationships played a dominant role within this hierarchical pattern, which were interpersonal models tied together by kinship, affinity, and geographical connections. Given that individuals were nodes within the network of ascribed relationships, the happiness of an individual unavoidably became intertwined with others, including family and the collective. This psychological process of considering oneself in relation to others beared a great resemblance to the concept of “moral circle”. The moral circle refered to the psychological structure in which individuals assess themselves and other entities from a moral standpoint, including the number of moral entities that mada individuals willing and able to bear moral obligations, as well as differences in the degree to which individuals feel a sense of moral duty and moral consideration across different moral circles (Yu & Xu, 2018). Drawing on the concept of the moral differential circle, this study put forth the structure of Chinese happiness as the “Happiness Circle.” The Happiness Circle referred to the psychological structure in which individuals consider their own happiness in relation to other entities, encompassing the extent to which individuals are willing to sacrifice their own happiness for the sake of others and the importance of others’ happiness to themselves. Under the influence of Chinese culture, an individual’s sense of happiness consisted of their own happiness and the happiness felt by others with whom they had social relationships. These social relationships may varied in terms of closeness and degree, collectively constituting the “Happiness Circle”.

1.3. How Chinese Cultural Values Affect Happiness

Since the reforms and opening-up policy in the 1980s, Chinese society has transitioned from a traditional society to a modern society. Consequently, there has been a gradual transformation in the mindset of Chinese individuals. Humility, which was once considered a virtue, has gradually shifted from being an admirable trait to a potential shortcoming. There was no longer a suppression of expressing positive emotions (Chiu, 2009). However, China’s modernity was not simply a complete Westernization, but rather it has the potential to form a “Chinese modernity” with distinct characteristics (Buzan & Lawson, 2020). In contemporary society, traditional Chinese culture was increasingly valued and there is a trend towards return. The rationality of traditional culture could compensate for the deficiencies of Western civilization, thus forming a unique modern civilization in Chinese society (Keightley, 2022). During this process, the psychological traditionality and modernity of individuals were not completely contradictory; rather, individuals often possess both traditional and modern attributes (Lu & Kao, 2002) As external cultural norms and products change, the internalized cultural concepted within individuals could be reflected in various aspects such as self-identity, thought patterns, and values (Cai et al., 2020). In the current social context, considering individuals with either psychological traditionality or modernity, which type of Chinese individual would be happier, or in other words, which cultural values would lead to greater individual happiness?

In previous research, most discussions on psychological traditionality or modernity and happiness have measured a single indicator of happiness. Researchers have compared cultural values and their relationship with happiness among university students in both Taiwan and the United Kingdom. Findings indicated that psychological traditionality have greater predictive power for happiness in Taiwanese students and social integration and interpersonal harmony only directly predict the happiness of Taiwanese students (Lu et al., 2001). Follow-up studies replicated these results, revealing that psychological traditionality have a stronger positive predictive effect on happiness (Xiao & Yu, 2020; Liu & Liu, 2016). However, as previously mentioned, China has currently entered a stage of socialist modernization, and therefore traditional values do not always predict positive outcomes. Some research has found that psychological traditionality are positively correlated with college students’ anxiety (Cui, 2016). Most studies involving Chinese cultural values have discussed the relationship between psychological traditionality and happiness but have overlooked the potential role of psychological modernity . Traditional Chinese governance relied on the benevolence and compassion of its people. Since encountering the Western world, the Chinese revolution has bred a unique emotional pattern that has had a significant impact on Chinese people and society. Contemporary China has commenced market-oriented reforms, thus breeding an emotion pattern dominated by consumerism (Jing & Chao, 2021). Therefore, how psychological modernity will impact happiness was a key focus area.

The ways in which cultural values impact happiness were quite diverse. Current research suggested that the fundamental reason for differences in how individuals define and perceive happiness across different cultures might stem from physiological differences. Firstly, Eastern and Western participants were observed to have different physiological neurobases in terms of emotional arousal. When researchers presented images of fearful faces to participants from Japan and Caucasians, respectively, fMRI results showed that while Caucasians activated the posterior cingulate gyrus, the supplementary motor cortex, and the amygdala in response to the stimulus, Japanese participants demonstrated significant activity in the right inferior frontal gyrus, the pre-supplementary motor area, and the left insula. These results indicates that Caucasians reacted to the fearful faces in a more direct and emotional manner (Moriguch et al., 2005). The same results were replicated in an electroencephalogram (EEG) study (Hot et al., 2006). All these studies indicate the influence of culture on fundamental emotional physiological responses, which may lead to differences in individual attitudes towards positive emotional states such as happiness and contentment.

Furthermore, cultural values influence individuals’ self-construction, leading to different self-concepts among people from diverse cultural backgrounds. Individualists perceived themselves and others as independent and autonomous, while collectivists view themselves as highly interconnected with others (Chiao & Cheon, 2012). Consequently, the content of well-being may also vary. Researchers have found that, compared to other-referencing, self-referencing engages the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex more actively in Chinese participants, consistent with findings from Western studies. However, when “mother-referencing” was included, activation patterns mirror those of self-referencing, providing evidence for the inclusion of maternal representations in the self-structure of Chinese individuals (Zhou et al., 2005). Concurrently, the same experiment was conducted with American participants, but this result was not observed, indicating from a neurophysiological standpoint that the self-concept of Chinese participants incorporates representations of their mothers, which is not the case for American participants (Zhu et al., 2007).

In summary, this study suggested that the sense of well-being among Chinese individuals should not be solely related to personal satisfaction, but rather to a “happiness circle “ that was connected to the people around them. Moreover, an individual’s cultural values influenced the degree of happiness and the distribution of the “happiness circle”. Based on previous research, it was difficult to hypothesize the predictive direction of psychological traditionality and modernity on happiness. However, it can be asserted that individuals with more psychological traditionality may allocate a larger proportion of their “happiness circle “ to relationships, while those who more psychological modernity may prioritize their own happiness within their “happiness circle”. The concept of “happiness circle” proposed in this study draws on the concept of the moral circle from previous research (Yu & Xu, 2018), aiming to establish a universal conceptual framework for happiness that can be applicable across cultures, contributing to the theoretical understanding of happiness. Furthermore, studying “happiness circle” can assist individuals in cultivating positive psychological states by understanding the constituents of an individual’s happiness, we can more effectively enhance their happiness and foster a healthy mindset.

This study aimed to explore the influence of psychological traditionality and modernity among Chinese individuals on their sense of happiness and the impact on the “happiness circle “ in Chinese culture. The experiment 1 measured the sense of happiness of Chinese participants at three levels: individual level, relationship level and societal level. This comprehensive investigation aimed to examine the effects of both psychological traditionality and modernity on the happiness of Chinese individuals and to demonstrate the significant role of family happiness in their overall sense of happiness. The study also soughted to provide evidence for the existence of the concept of “happiness circle “. In Experienment2, we constructed the constituents of “happiness circle “ for Chinese participants. By using tasks such as “happiness token distribution” and “happiness importance survey”, we investigated the extent to which others’ happiness contributes to the sense of happiness among Chinese individuals. This task helped draw a depiction of “happiness circle “ for Chinese participants.

2. Experienment1: The Influence of Psychological Traditionality and Modernity among Chinese Individuals on Happiness

2.1. Participate

Four hundred and fifty participants (252 males, Mage = 24.93, SD = 6.22) completed the study on the

https://www.wjx.cn/. Participants completed several scales on Online Website to earn money. Participants first completed basic graphic information including gender, age, education level, subjective and objective social class as control variables. Then participants read the questionnaire instructions and signed the informed consent form. The entire questionnaire took approximately 20-25 minutes to answer.

2.2. Measurement

In this study, the “Individual Multidimensional Traditionality and Modernity Scale” was utilized to measure psychological traditionality and psychological modernity. Additionally, separate questionnaires were employed to measure individual-level, relational-level, and societal-level happiness. Furthermore, classic questionnaires were used to measure self-esteem (Martín et al., 2007) and the trait level of interdependence (Rossi, 2008) as control variables.

Individual Multidimensional Traditionality and Modernity Scale (Bai et al., 2016). The scale consisted of two sub-scales, Traditionality and Modernity, which were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Each sub-scale includes five dimensions. The Traditionality sub-scale comprises the following dimensions: Middle Way Mentality (e.g. Individuals should constantly examine their behaviors and correct their mistakes), Fatalistic Superstition (e.g. The success or failure of every individual is predestined), Male Superiority (e.g. Men are the heads of the family and should make decisions regarding family matters), Relationship Orientation (e.g. Before making decisions, one should consider the opinions of others), Filial Piety and Respect for Elders (e.g. Younger generations should show respect and obedience to their older relatives). The Modernity sub-scale includes the following dimensions: Fairness and Justice (e.g. Basic human rights should be protected in a democratic society), Consumption Orientation (e.g. Life should include enjoying good food, clothing, and housing), Internal Locus of Control (e.g. No matter how unfavorable the environment, as long as a person works hard and perseveres, they will eventually succeed), Quest for Novelty and Change (e.g. People should have diversified interests and be willing to learn new things), Independence and Autonomy (e.g. People of different religious beliefs can still be friends). The total scores of the two sub-scales represented the levels of psychological traditionality and psychological modernity. Higher scores indicated a greater identification with these cultural values.

At the individual level, the measurement of happiness included three scales:

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS, Pavot & Diener, 1993). This scale consisted of five items rated on a 7-point scale. A higher total score indicated greater overall satisfaction with life.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS, Liang & Zhu, 2015). This scale measured both positive and negative emotions rated on a 5-point scale.

PERMA Scale (PERMA, Butle & Kern, 2015). The PERMA Scale assessed happiness across five dimensions: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement. It consisted of 16 items, and the average score for each dimension represents its respective aspect. The average score across all 16 items reflected the overall happiness.

At the relationship level, the measurement of happiness included two scales:

Satisfaction With Family Scale (SWFS): This scale was an adaptation of the SWLS specifically designed to measure an individual’s perception of their family members’ satisfaction with life. The scoring method was the same as the SWFS mentioned earlier.

Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWB, Ryff, 1989): This scale assessed various dimensions related to self-realization.Only the dimension of “Positive Relationships” was measured in this study. Higher scores on this dimension indicated that individual”has warm, satisfying, trusting relationships with others, is concerned about the welfare of others, capable of strong empathy, affection, and intimacy, understands give and take of human relationships.

At the societal level, the measurement of happiness included one scale:

Social Well-Being Scale(SWBS, Keyes, 1998): This scale consisted of five dimensions, social acceptance, social actualization, social contribution, social coherence and social integration. In total, there were 15 items rated on a seven-point scale. The version used in this study does not require reverse scoring of any items, with higher total scores indicating higher levels of social well-being.

Since the measurement scales for different aspects of happiness assess specific facets within the concept of happiness, it was not appropriate to combine the results from different scales. Therefore, in the subsequent analysis, this study separately analyzed the influence of psychological traditionality and modernity on different aspects of happiness across various facets.

2.3. Results

Out of the initial sample of 450 participants, 32 individuals did not complete the experiment in its entirety or did not pass the screening question (e.g., selecting “4” for a specific item). As a result, a total of 418 participants were included in the subsequent analysis.

2.3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Related Analysis

Based on the study, controlling for variables such as gender, age, subjective and objective social class, as well as self-esteem and interdependence, the correlations between psychological traditionality and modernity (treated as continuous variables) and different levels of happiness were examined. The Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated, and the results are presented in

Table 1 (a-d). The findings indicated that psychological traditionality positively correlates significantly with SWLS, positive emotions, PWB_PR and Societal-Level Happiness (

ps <0.05). On the other hand, psychological modernity positively correlated significantly with SWLS, positive emotions, PERMA, family well-being, and Relational-Level Happiness (

ps <0.05).

To explore whether there were differences in the correlations between psychological traditionality and modernity and different levels of happiness, Steiger’s Z test was conducted on the correlation coefficients between different levels of happiness and psychological traditionality and modernity. The results were shown in column E of

Table 1. The findings suggested that the differences in the impact of psychological traditionality and modernity on various levels of happiness are particularly pronounced at negative emotions and at societal-level happiness (

ps <0.05). There was also a marginally significant difference (

p = 0.057) in the correlation coefficients between the two cultural values and relational-level happiness.

2.3.2. Regression Analysis

The aforementioned results suggested that there are differences in the correlations between psychological traditionality, modernity, and happiness at different levels. Following this, regression analysis was conducted with different levels of happiness as the dependent variables, psychological traditionality and psychological modernity values as the independent variables, and age, gender, self-esteem, and subjective and objective social class as control variables. This analysis aimed to explore the predictive roles of psychological traditionality and psychological modernity values in different levels of happiness. The results are presented in

Table 2.

The regression analysis results indicated that psychological traditionality significantly predicts SWFS and Societal-Level Happiness at the individual level (ps < 0.05). On the other hand, psychological modernity significantly predicted SWLS, negative emotions, PERMA, and relational-level happiness (ps < 0.05).

Importantly, it should be noted that the predictive effects of psychological traditionality and psychological modernity on emotions at the individual level of happiness were entirely different. Psychological traditionality positively predicted positive emotions (p < 0.001) and negatively predicts negative emotions (p < 0.001) . This suggested that individuals with higher psychological traditionality may have more positive emotions and hence were happier at the individual emotional level. On the other hand, psychological modernity did not predict positive emotions significantly (p = 0.429) and positively predicted negative emotions (p < 0.001) . This may indicated that individuals with higher psychological modernity exhibited more negative emotions and, consequently, were less happy at the individual emotional level. Furthermore, at the relational level of happiness, psychological traditionality and psychological modernity also played different roles. Psychological traditionality positively predicted SWFS significantly (p = 0.039), while not predicting PWB_PR (p = 0.497). On the other hand, psychological modernity significantly and positively predicted PWB_PR (p < 0.001), but did not predict SWFS (p = 0.101) significantly. At societal-level happiness, psychological traditionality had a positive predictive effect (p < 0.101), while psychological modernity did not (p = 0.772) .

2.4. Discussion

In Experiment 1, a questionnaire method was employed to collect data on individual psychological traditionality and psychological modernity cultural values, as well as data on different levels of happiness. Through correlation and regression analyses, it was found that individuals with psychological traditionality or psychological modernity have different experiences of happiness across different levels. At the individual-level of happiness, regardless of cultural values held, individuals report higher life satisfaction and PERMA. It was suggested that individuals with higher psychological traditionality may experience more positive emotions, while those with higher psychological modernity may experience more negative emotions. At the relational level of happiness, individuals with psychological traditionality tended to have higher satisfaction in their family life, while individuals with psychological modernity tend to experience higher relational happiness. At the societal level of happiness, individuals with higher psychological traditionality were more likely to experience higher levels of happiness.

This finding confirmed the existence of dimensions of happiness as proposed in previous research, highlighting social and individual differences (Gao et al., 2010). The role of psychological traditionality in happiness confirmed previous research findings, demonstrating that individuals with Chinese traditional cultural values tended to have higher family happiness (Yang & Zhou, 2017) and social happiness (Liu et al., 2018). However, an interesting result emerged where individuals with psychological modernity reported higher relational-level happiness compared to those with psychological traditionality. This might be due to the difference in the concept of relationships in modern Chinese society. Chinese psychological traditionality placed emphasis on sacrificing one’s own interests to fulfill others’ needs. Researchers investigating the impact of cultural values of Chinese business managers on employee work efficiency found that non-traditional managers were able to stimulate higher work efficiency and elicit more positive responses to motivation (Zhang et al., 2014). Additionally, in the context of research on the adaptation of Chinese university students, it was found that students with lower levels of traditional beliefs may have higher self-efficacy and better adaptation (Guan et al., 2016). These findings contributed to our understanding of the impact of cultural values on happiness and highlight the need to consider both psychological traditionality and modernity when studying happiness in Chinese society.

In addition, building on the findings from Experiment 1, we can predict the constituents of happiness perspectives for individuals with psychological traditionality and modernity. It was expected that societal-level happiness may be more important for individuals with psychological traditionality compared to the findings presented in

Figure 1. This finding aligned with expectations, as individuals with traditional cultural values tend to place more emphasis on collective sentiments. Some researchers argued that, within Chinese culture, individuals defined happiness as satisfying their social self-esteem (Zhang, 2000). Moreover, individuals with tended to adhere more to social norms and experienced happiness through adhering to these norms (Wang, X., & Zhang, C., 2020).

To summarize, the results of Experiment 1 indicated that individuals with different cultural values have different experiences of happiness on different levels. Now, a question arises: Is the importance of happiness at different levels equivalent for individuals? In Experiment 2, a “happiness token distribution” and a “happiness importance survey” were employed to explore the composition of happiness circles for individuals with psychological traditionality and modernity.

3. The Happiness Circles for Individuals with Psychological Traditionality and Modernity

3.1. Participant

Two hundred and Eighty participants(156 males, Mage = 25.10, SD = 6.23) completed the study on the

https://www.wjx.cn/ as in Experienment1. Participants also completed several scales on Online Website to earn money. Participants also completed basic information including gender, age and education level. Then participants read the questionnaire instructions and signed the informed consent form. The entire questionnaire took approximately 10-15 minutes.

3.2. Procedure

The happiness token distribution task can be designed based on previous research on the importance of attitudes towards others (Waytz et al., 2019). Participants were informed, “Suppose you currently have 100 happiness units. How many units would you be willing to allocate to the following groups?” The groups were presented in the following order, from closer relationships to more distant relationships: Yourself, Parents, Descendants, Brothers and sisters, Other family members, Relatives, Friends, Neighbors, Teachers or students, Co-workers, Compatriots (excluding the above options), People from the same town (excluding the above options), People from the same country (excluding the above options), People from other countries (excluding the above options). All options were presented sequentially on the same screen, with participants having a total of 100 tokens to allocate. If participants allocated all their tokens before reaching the end, they could reduce the amount allocated in previous categories. If participants reached the end without allocating all their tokens, they were prompted to redistribute the remaining units. After confirming the allocation of happiness tokens, participants clicked on “Confirm and Submit” to finalize their allocation.

Evaluation of Importance of Happiness Task: This part of the experiment asked participants to answer the question, “How important do you think the happiness of the following individuals is to your happiness?” Participants were required to give a score from 0 to 100 for each group, presented in the same order as in the happiness token allocation task. The order of presentation of the two tasks was randomized.

The Individual Multidimensional Traditionality and Modernity Scale was same as in Experienment1.

3.3. Results

Nineteen participants did not complete the questionnaire in its entirety, resulting in 261 participants included in the subsequent data analysis. The data was analyzed using SPSS 25.0.

The results of the task evaluating the allocation of happiness tokens and importance ratings were shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the differences in happiness token distribution. The results indicated significant differences among individuals in happiness token distribution, F(1.13) = 421.07,

p < 0.001,

ηp2 = 0.601. Post-hoc LSD tests revealed significant differences in the allocation of happiness tokens between the categories of “Yourself,” “Parent,” “Descendants,” and “Brothers and Sisters” and the other categories (

ps < 0.001). No significant differences were found between “Other family members” and “Friends” (

p > 0.05), but both categories exhibited significant differences compared to the other categories (

ps < 0.001). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in token distribution between the category “Relative” and “Teachers or Students” (

p = 0.326), but both categories showed significant differences compared to the other categories (

ps < 0.001).

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the differences in the evaluation of importance of happiness. The results indicated significant differences among individuals in their evaluation of importance, F(1.13) = 239.08, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.461. Post-hoc LSD tests revealed no significant differences in the evaluation of happiness importance between the categories of “Yourself” and “Parents” (p = 0.328), but both categories showed significant differences compared to the category of “Descendants” (p yourself-descendants = 0.001, p parents-descendants = 0.014). These three categories exhibited significant differences in token allocation compared to the other categories (ps < 0.001). Interestingly, there were no significant differences between the categories of “Other family members” and “Friends” (p = 0.799), and there were no significant differences between “Relatives” and “Teachers or Students” (p = 0.148). These findings corroborated the results of the happiness token distribution task.

To construct the happiness circle, the results of the happiness token distribution task and evaluation of importance of happiness task were separately transformed into z-scores and then standardized and combined by summation, resulting in the happiness circle scores. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the happiness circle scores of the 14 categories, allowing for free extraction of factors, KMO measure yielded a value of 0.874, while the Bartlett’s test of sphericity demonstrated a significant result (p < 0.001), signifying that the data was appropriate for factor analysis. A principal component analysis was then conducted on the correlation matrix, utilizing the factor extraction criterion of eigenvalues greater than 1 and employing varimax rotation. The cumulative variance contribution rate of the four resulting factors amounted to 69.61% (see

Table 3). The four levels of happiness circle references were traditionally named as follows based on previous research: Happiness for self only (HSO, yourself), Happiness for ascribed relationships (HAR, Parents, Descendants, Brothers and sisters), Happiness for interactive relationships (HIR, Other family members, Friends), Happiness for social (HS, Relatives, Neighbour, Co-workers, Compatriots who do not include the above options, People from the same town who do not include the above options, People from the same country who do not include the above options, people from other countries who do not include the above options). In the subsequent analysis, the average happiness circle scores for the categories included in different levels (HSO, HAR, HIR, HS) will be plotted to visualize the happiness circle.

To investigate the influence of cultural values on the happiness circle, participants were classified based on previous research (Chipman & Berry, 2020). They were categorized into four groups: high traditionality & high modernity, high traditionality & low modernity, low traditionality & high modernity, and low traditionality & low modernity. The specific process involves arranging individuals’ traditionality and modernity scores in ascending order and assigning a value based on the median, thereby distinguishing the four groups (refer to

Figure 4).

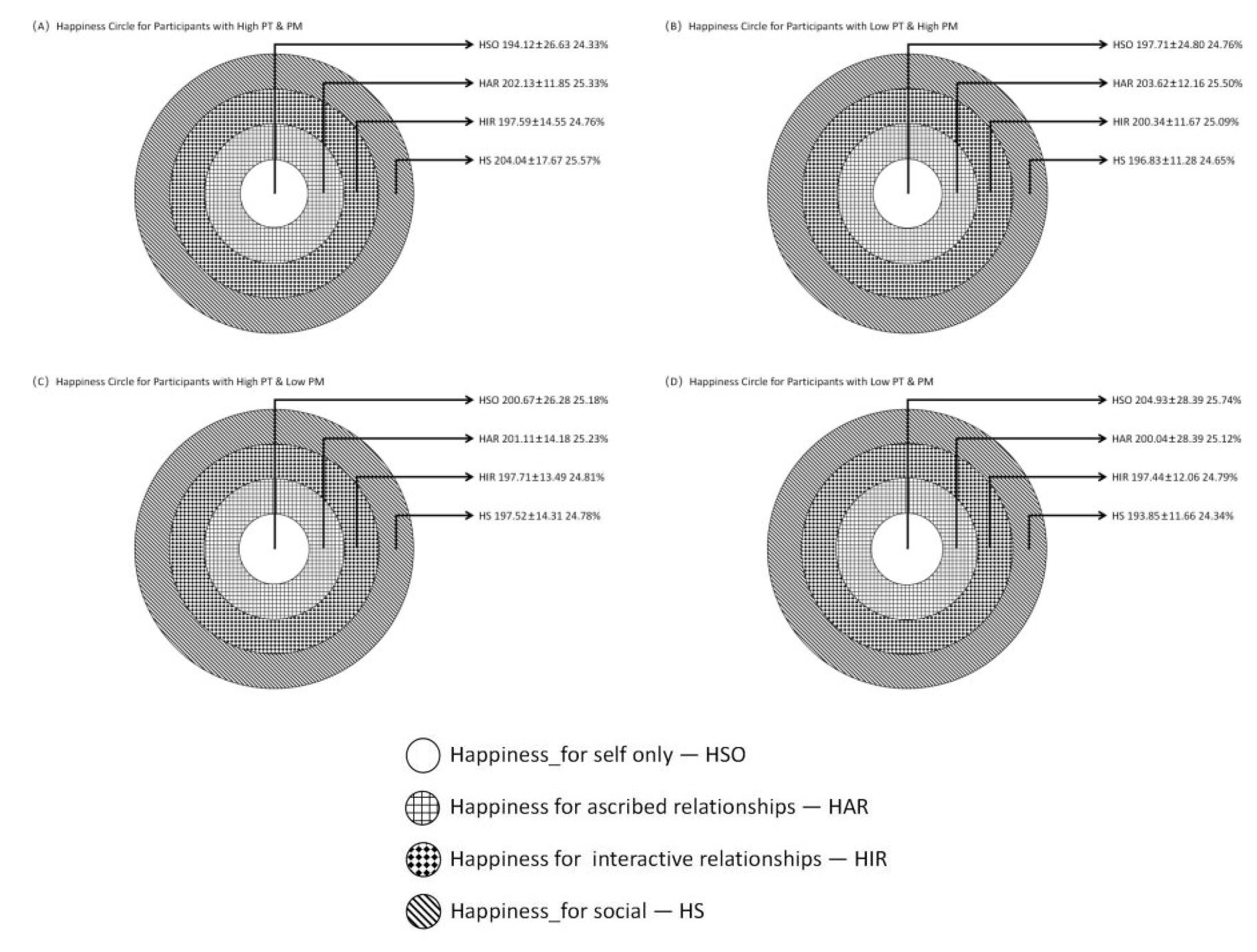

The happiness circle for the four types of individuals were as follows (see

Figure 5). Although the differences were not substantial, it was still evident that individuals with different cultural values exhibit varying levels within the happiness circle. The results of the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) also indicated that the differences mainly manifest in the “Happiness for Self Only” and “Happiness for Social” levels. In the “Happiness for Self Only” level, F(3,258) = 3.846,

p < 0.01,

ηp2 = = 0.23. Post-hoc LSD tests revealed that individuals in LTLM group had the highest happiness circle scores in “Happiness for Self Only” level, significantly different from individuals in HTHM and HTLM groups (

ps < 0.05). The result also suggested that for LTLM individuals, their own happiness was considered more important than any other levels of happiness.

In the “Happiness for Social” level, F(3,258) = 4.521, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.15. LSD post-hoc tests indicated that individuals in LTHM and LTLM groups had the lowest happiness circle scores in the “Happiness for Social” level, significantly different from individuals in the HTHM and HTLM groups (ps < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference between the LTHM and LTLM groups (p > 0.05) in this level.

To further analyze the impact of psychological traditionality and psychological modernity on the happiness circle, regression analyses were conducted with the different levels of happiness circle scores as outcome variables, psychological traditionality and psychological modernity values as predictor variables, and age and educational level as control variables. The results were presented in

Table 4. The regression analysis results indicated that psychological traditionality negatively predicts happiness circle scores in the “Happiness for Self Only” level (

p =0.08) and positively predicts happiness circle scores in the “Happiness for Interactive Relationships” level (

p =0.001) .On the other hand, psychological modernity positively predicted happiness circle scores in the “Happiness for Ascribed Relationships” (

p =0.005) , “Happiness for Interactive Relationships” (

p =0.001)and “Happiness for Social” levels (

p =0.049).

3.4. Discussion

Study 2 investigated the concept of the happiness circle among Chinese individuals through the utilization of two tasks: the happiness distribution token task and the task of evaluating importance of happiness. The happiness distribution token task was a representation of an individual’s willingness to contribute towards another person’s happiness, where a greater quantity of tokens offered indicates a higher willingness to dedicate personal resources for the happiness of others. On the other hand, the Task of Evaluating Importance of Happiness directly measured the significance of others’ happiness in relation to one’s own happiness. By combining these two dimensions, we defined the concept of the “happiness circle.” The results indicated that within the happiness circle of Chinese individuals, there were several levels: Happiness for oneself only, Happiness for Ascribed Relationships, Happiness for Interactive Relationships, and Happiness for social. Furthermore, it was observed that the hierarchy of these levels within the happiness circle was similar across different individuals.

Although the happiness circles of individuals categorized as High PT&PM, High PT&Low PM, Low PT&High PM, and Low PT&PM may appear visually similar, their compositions differed. LTLM individuals placed the highest importance on Happiness for oneself only, considering their own happiness to be more significant than that of ascribed relationships, interactive relationships, and societal happiness. This could be attributed to the lower levels of relationship and social identification among individuals with low levels of both PT and PM, which lead them to prioritize their own happiness above all else. On the other hand, the Happiness for Ascribed Relationships and Happiness for Interactive Relationships levels actually represented relational-level happiness. However, there were no significant differences observed among the various types of individuals at this level, suggesting that regardless of their personal values, Chinese individuals tend to have a similar perception of happiness derived from relational factors. Future research could further explore the differences in this aspect of happiness among different groups within cross-cultural samples. Regarding the societal-level happiness, irrespective of psychological modernity, individuals with low psychological traditionality exhibited the lowest level of importance placed on this aspect of happiness. Furthermore, combining the results from the regression analysis, individuals holding psychological traditionality considered interactive relationships (Friends, Other family members) happiness to be most important, while their own happiness and that of their ascribed relationships were perceived as less significant. In fact, psychological traditionality even negatively predicted the scores of the happiness circle for Happiness for oneself only.

In traditional Chinese culture, individuals were expected to adhere to values that emphasize obedience and maintaining good social relationships. However, this study did not find evidence to support this finding. One possible reason for this disharmony could be that, in modern society, individuals influenced by traditional culture do not fully understand or internalize traditional values (Fong, 2007). This lack of understanding may lead to a disregard for the happiness derived from intimate relationships, such as oneself, parents and children, and siblings. On the other hand, individuals influenced by modern cultural may have developed a more comprehensive set of values that align better with Chinese relationship-oriented values.

The relationship between psychological traditionality and societal-level happiness differed from the findings of Study 1. This discrepancy could be due to the fact that psychological traditionality is not necessarily a condition that promotes concern for the collective, but rather a boundary condition that helps individuals protect themselves from potential harm caused by the collective. Previous research has found that individuals with higher levels of psychological traditionality were more likely to adhere to prohibitive rules that prevent actions harmful to the collective (e.g., littering), while the same response was not observed for prescriptive rules (Wang & Zhang, 2020). Additionally, other studies have found that Chinese psychological traditionality could mitigate the negative impact of exploitative leadership on employees, buffering against harm and moral detachment (Cheng et al., 2021). Therefore, it was possible that psychological traditionality does not have the anticipated impact on societal happiness as previously assumed.

4. General Discussion

Our research employed two experiments to investigate the influence of psychological traditionality and modernity on the different levels of happiness among Chinese individuals. It confirmed the existence of the happiness circle and explored the impact of psychological traditionality and modernity on the happiness circle among the Chinese population.

This study was based on the different levels of happiness perceptions among Chinese individuals, which were divided into individual, relational and societal level happiness. The hierarchical structure of the happiness circle was established in experiment1 and further refined in experiment 2. Specifically, it included Happiness for self only, Happiness for Ascribed and interactive relationships, and Happiness for social. The philosophical origin of the term “Happiness” was only encompassed within the Happiness for self only level, where it was considered beyond human capacity and subject to luck and divine control (Oishi et al., 2013). However, the notion of happiness measured in this study was related to individual efforts, as individuals strive to pursue and contribute to the happiness of others or society. Previous research suggested that collectivist cultures may be more likely to develop a luck-based notion of happiness due to their association with external locus of control (Triandis, 2001). However, the structure of the happiness circle in this study revealed that individuals in China, a collectivist country, whether influenced by psychological traditionality or psychological modernity, were willing to make efforts to contribute to the happiness of others or society.

Happiness perceptions were generally positively correlated with indicators of relationship identification and relationship satisfaction across different cultures (Hill et al., 2013). This finding was also corroborated by the current study, as Happiness for relation (the combined measure of Happiness for Ascribed Relationships and secondary intimacy) constituted a significant portion within the happiness circle of Chinese individuals (mean = 50.16%). Previous research had also highlighted the importance of establishing positive relationships with others as a pathway to individual happiness (Pittman, 2018).

In Study 1, the measurement of Happiness for social utilized the Social well-being questionnaire, some items of which overlap with the measures employed in Study 2. However, Study 2 did not include a direct measurement of the broader concept of “society,” such as “perceptions of the societal improvement”. This was because the focus of the current study’s happiness circle pertains to the individual’s perception of their own happiness and their willingness to make efforts to enhance the happiness of others. The entity of “society” did not inherently experience happiness or unhappiness proactively. Future research could potentially expand on the concept of the happiness circle by incorporating other aspects related to societal happiness.

Another primary research question of this study aimed to explore the impact of cultural shifts on different levels of happiness and the happiness circle. In the process of global modernization, modern society had received considerable criticism, being accused of degrading the quality of life and making people less happy. However, comparisons across 141 countries reveal that people living in modernized societies tended to be happier (Veenhoven & Berg, 2013). Further research even posited that modernity was a decisive factor in life satisfaction (Veenhoven, 2018). This study, taking place within the context of China’s current process of modernization, discussed the impact of internalized psychological modernity on happiness. Findings from Experienment1 revealed that individuals with a higher degree of psychological modernity experienced a higher relational-level happiness but also more negative emotions, and lower family satisfaction and societal-level happiness. Results from Experiment 2 suggested that psychological modernity was indeed predictive of the degree of importance placed on happiness of societal and ascribed relationships . This may explained why Experiment 1 found that individuals with higher psychological modernity, despite their strong emphasis on societal happiness and happiness in ascribed relationships (family), may feel disappointment due to these high expectations, thereby resulting in lower family satisfaction and societal happiness. Indeed, an individual’s social capital and the degree of emphasis they placed on social relationships can predicted their happiness (Leung et al., 2013). Additionally, both an individual’s psychological traditionality and modernity could positively predict their happiness. Previous research has found that an individual’s level of cultural fit can predict their happiness (Oishi & Gilbert, 2016). The results of this study have indirectly demonstrated that current Chinese society indeed encompasses both traditional and modern characteristics.

This study did not confine itself to the exploration of life satisfaction but expanded the research on happiness to the individual, relational, and societal levels. By measuring the importance individuals assign to different levels of happiness and their willingness to contribute to others’ happiness, the study mapped out the individual’s happiness circle. This was because while life satisfaction has often been correlated with or considered the core of happiness, our evaluation of life is essentially arbitrary. Additionally, most people did not frequently assess their life satisfaction. Therefore, these attitudinal measures may not accurately reflect a carefully considered sense of happiness (Hitokoto & Uchida, 2015). The willingness of individuals to allocate their “happiness tokens” to enhance others’ happiness and the importance they assign to others’ happiness can better reflect the distribution of an individual’s happiness circle. Compared to individual happiness, the happiness circle has a stronger predictive role for mental health (Burns & Crisp, 2022).

The findings of this study revealed that individuals with higher adherence to psychological traditionality do not exclusively exhibit other-oriented tendencies, but also demonstrate higher levels of self-orientation. This result contradicted previous beliefs that Chinese individuals were predominantly other-oriented (Maercker et al., 2015; Mengyu, 2008). Moreover, the conclusion that Chinese individuals were more other-oriented has been derived through comparisons with Western cultures in previous studies. Hence, when describing Chinese individuals, it was essential to avoid solely focusing on their other-oriented tendencies and instead consider both self-orientation and other-orientation within a cross-cultural framework.

While this study has yielded meaningful results and proposed the concept of a “Happiness Circle” based on the “hierarchy of differences,” it was important to acknowledge that the research methodology employed was relatively limited. The reliance on subjective reports may introduce biases due to social desirability, as individuals may prioritize reporting happiness in intimate relationships and societal happiness. Future research could incorporate implicit association tests to further investigate the concept of the Happiness Circle. Additionally, the visualization method used for the Happiness Circle departs from traditional heat maps, as it involved converting ratings into heat maps. If participants were directly asked to drag and determine the sizes of different happiness circles within a circular diagram, it may yield more pronounced differences in the collected results and provide a clearer understanding of variations among different groups. Lastly, it was worth noting that this study focused on Chinese undergraduate students who generally do not have established romantic relationships. Consequently, the Happiness Circle examined in this study does not include the happiness experienced by romantic partners, which may be a crucial component of the Happiness Circle. While acknowledging the valuable findings and the introduction of the concept of the Happiness Circle, future research should consider incorporating diverse methodologies such as implicit measures, alternative visualization techniques, and the inclusion of romantic partner happiness to enhance the understanding of this construct.