1. Introduction

Chagas disease is a neglected tropical infection caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, affecting millions of people worldwide (Coura and Viñas, 2010; De Fuentes-Vicente et al., 2023; Perez-Molina and Molina, 2018; Perez-Molina et al., 2015; Porta et al., 2023). While initially concentrated in Latin America, the disease has spread to non-endemic continents via the immigration of infected individuals (Abras et al., 2022; Angheben et al., 2015; Assal and Corbi, 2011; De Fuentes-Vicente et al., 2023; Gascon et al., 2010; Monge-Maillo and Lopez-Velez, 2017; Perez-Molina et al., 2015). Transmission can occur via contact with infected triatomine feces, congenital transmission, blood transfusion, laboratory accidents or oral infection (Bern, 2015; Bocchi, 2018; Bonney et al., 2019; Lopez-Garcia and Gilabert, 2023; Shikanai-Yasuda and Carvalho, 2012). Following the acute phase, which typically lasts around two weeks, patients enter the chronic phase, where approximately 30-40% of individuals develop clinical manifestations such as digestive, cardiac, and cerebral alterations (De Fuentes-Vicente et al., 2023; Saraiva et al., 2021; Tanowitz et al., 2015). The clinical manifestations of Chagas disease are divided into two phases: acute and chronic (Malik et al., 2015). In the acute phase that begins 6 to 10 days after infection and lasts from 4 to 8 weeks depending on the parasite strain (Steverding, 2014), some patients might exhibit clinical signs such as "Chhagoma" and/or Romaña's sign, sometimes even arrhythmia, but less than 5% of patients exhibit more severe signs and symptoms (Malik et al., 2015). Following the acute phase, 60–70% of patients develop an indeterminate chronic disease that is characterized by positive serology but is clinically asymptomatic (Rassi et al., 2010). After 10–30 years after infection, 30–40% of patients develop symptoms that include severe cardiac complications such as left ventricular dilation and dysfunction, ventricular arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction (Malik et al., 2015).

In the context of host-pathogen interactions, extensive research has been conducted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved (Schenkman and Eichinger, 1993; Torrecilhas et al., 2020). T. cruzi molecules have been identified and characterized by highlighting their ability to activate macrophages and induce the production of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines (Camargo et al., 1997; Campos et al., 2001; Campos et al., 2004; Martins et al., 2015; Monteiro et al., 2006; Nakayasu et al., 2012; Procópio et al., 2002). Molecules anchored by glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) and trans-sialidase (TS) expressed by T. cruzi play crucial roles in triggering immune re-sponses and stimulating the production of inflammatory mediators (Almeida et al., 2000; Almeida et al., 1999; Almeida and Gazzinelli, 2001; Camargo et al., 1997; Campos et al., 2001; Campos et al., 2004; Monteiro et al., 2006).

EVs have emerged as key players in intercellular communication and modulation (Colombo et al., 2014; Lotvall et al., 2014; Théry et al., 2006; Théry et al., 2009; Théry et al., 2018; Théry et al., 2002; Tkach and Thery, 2016). These membrane-derived vesicles can be classified into microvesicles, exosomes and apoptotic bodies, each with distinct biogenesis, release pathways, size, content, and function (Théry et al., 2018; Théry et al., 2002). Previous studies have demonstrated that T. cruzi trypomastigotes release EVs containing glycoproteins, including TS, gp85 and mucin, which play essential roles in modulating the host innate immune response (Soares et al., 2017; Torrecilhas et al., 2012; Torrecilhas et al., 2020; Trocoli Torrecilhas et al., 2009). In Chagas disease, these glyco-proteins serve as targets for lytic anti-αGal antibodies, which contribute to the control of parasitic infection (Almeida et al., 2000).

Our recent investigations have shown decreased concentrations of EVs released by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in chronic Chagas disease patients compared to healthy individuals (Madeira et al., 2021). This finding supports observations from circulating EVs in patients (Madeira et al., 2021; Madeira et al., 2022). Given the importance of EVs in T. cruzi infection and their potential implications, we aim to characterize EVs present in the plasma of patients experiencing reactivation of chronic Chagas disease. Additionally, we will examine the expressions of αGal and TS, furthering our under-standing of the complex interplay between EVs and T. cruzi in Chagas disease.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of Universidade Federal de Sao Paulo, (CEP/UNIFESP - CAAE: 70749317.2.0000.5505). Samples were obtained from Chagasic patients and healthy individuals (controls) who willingly provided written informed consent. Our study enrolled subjects with a confirmed positive serology for Chagas disease, without any limitations on gender or age. Control individuals had a negative serology for Chagas disease.

2.2. Healthy Controls, Patients, Clinical Samples, and Laboratory Diagnosis.

The control group comprised 30 health individuals, tested negative for Chagas Disease, and had no known medical conditions at the time of sample collection for the isolation EVs from plasma. The samples’ patients consist of 44 plasmas collected from patients diagnosed with Chagas disease over a period of 12 months, specifically from December 2018 to November 2019. The patients included in the study were diagnosed with Chagas disease both clinically and with laboratory tests and were categorized into different groups based on their clinical characteristics; Group I consisted of patients who experienced a recurrence of infection due to immunosuppressive treatment after undergoing transplantation or cancer therapy. These patients were selected to investigate the presence of Chagas disease recurrence in the context of immunosuppression; Group II comprised patients with CCD, focusing on individuals with persistent infection and long-term clinical manifestations of the disease. These patients were selected to analyze the presence of Chagas disease markers in patients with established chronic infection; Group III consisted of patients with a co-infection of HIV and Chagas disease. This subgroup was included to assess the impact of HIV co-infection on the clinical presentation and molecular characteristics of Chagas disease. For the molecular diagnosis of Chagas disease, blood samples were collected in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as an anticoagulant. The samples were then sent to Instituto Adolfo Lutz in São Paulo, Brazil, for further analysis. To extract the DNA, the blood samples were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 1,850 g and the resulting blood pellets were utilized. To proceed with DNA extraction, the cells obtained from the blood pellets were digested using 20 µg of proteinase K in AL buffer (Qiagen). Subsequently, DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purity and concentration of the extracted DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer. To detect the presence of T. cruzi DNA, a real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed. A specific primer set, T.cruzi 32/148, was used for amplification. This primer set consisted of the forward primer 32 (5′ TTTGGGAGGGGCGTTCA-3′) and the reverse primer 148 (5′ ATATTACAC-CAACCCCAATCGAA-3′). The MGB TaqMan probe 71 (5′ CATCTCACCCGTACATT3′) was labeled with FAM and NFQ at the 5' and 3' ends, respectively, and used for detection. All 44 patients included in the study tested positive for T. cruzi via qPCR, indicating the presence of the parasite's DNA in their blood samples. This confirmed the diagnosis of Chagas disease in the patient cohort and provided a basis for further analysis of the clinical and molecular characteristics associated with the different patient groups. Overall, this comprehensive evaluation of plasma samples from patients diagnosed with Chagas disease revealed the persistence of T. cruzi DNA in all cases. The categorization of patients into distinct groups allowed for the examination of specific aspects related to disease recurrence, chronic infection, and co-infection with HIV. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the molecular features and clinical implications of Chagas disease in different patient populations.

2.3. Isolation and Characterization of EVs from Human Plasma Samples from Healthy Controls and Patients.

The protocol employed in this study was based on the methodologies described by Madeira et al. (2022 and 2021). To perform ultra-centrifugation of plasma samples, a fixed angle rotor, specifically the Thermo Scientific™ T-8100 Fixed Angle Rotor, was utilized. The ultra-centrifugation process was carried out using the Thermo Scientific™ Sorvall™ WX100 Ultra Centrifuge, with a centrifugal force of 100,000 g, for a duration of 1 hour. To initiate the ultra-centrifugation process, 1 mL of plasma sample was carefully transferred to a suitable centrifuge tube. It is important to note that proper handling and preparation of the samples are critical to ensure reliable and reproducible results. The use of sterile techniques, such as working in a laminar flow hood and wearing appropriate personal protective equipment, is recommended to minimize the risk of sample contamination. Once the plasma samples were loaded into the centrifuge tubes, the tubes were securely sealed to prevent any leakage or loss of sample during the centrifugation process. It is essential to select centrifuge tubes that are compatible with the rotor being used, to ensure optimal performance and safety. During the ultra-centrifugation process, the centrifuge operates at a force of 100,000 x g, subjecting the plasma samples to a strong gravitational field (Madeira et al., 2021; Madeira et al., 2022).

In the next step, we performed size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). Initially, the filtered samples (0.1 mL) were adjusted to a volume of 1 mL using a 100 mM ammonium acetate solution at pH 6.5. These EVs samples were subsequently loaded into a Sepharose CL-4B column (1 x 40 cm, Cytiva), which had been pre-equilibrated with 100 mM ammonium acetate at pH 6.5. The column was then eluted with the same buffer at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. In total, 30 fractions, each of 1 mL, were collected. These fractions were further screened using CL-ELISA, following the methods outlined in a prior publication by our group (Madeira et al., 2022). Dot Blot protocol, a nitrocellulose membrane (NM) was employed, with a grid drawn on it to demarcate the blotting region. Subsequently, 5 μL (103 particles/spot) of each EV sample was spotted at the center of the grid, and the membrane was left to air-dry at room temperature (RT). Following this, it was blocked overnight with 5% nonfat milk in TBS. The NM was then exposed to the following antibodies: (i) rabbit polyclonal anti-human CD9 (Thermo Scientific 11559); (ii) monoclonal anti-human CD63 (Immunostep, 63PU); (iii) monoclonal anti-human CD81 (Thermo Scientific 80820); and (iv) monoclonal anti-human CD82 (Thermo Scientific 27233). All antibodies were diluted at 1:500 in TBS with 5% nonfat milk. After incubating for 1 hour at RT, the NM underwent TBS-T washing and then were exposed to anti-rabbit IgG-peroxidase conjugate or anti-mouse Ig-peroxidase (both from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) at a 1:5,000 dilution in TBS nonfat milk for 1 hour. After five additional washes in TBS-T, the peroxidase signals were detected by introducing a chemiluminescent (ECL) solution (A-38555, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated in the dark for 10 to 15 minutes, with images acquired using an Odyssey C imaging system (Li-Cor). For Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), EVs isolated from both HC and patients’ samples, obtained via size-exclusion chromatography as previously detailed (Madeira et al., 2022), were examined to assess their size and structural integrity. The EVs were fixed in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer at pH 7.2 and post-fixed in a 1% osmium tetroxide solution in the same buffer. After dehydrating in a series of acetone gradients, the samples were embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections were produced using a Reichert ultramicrotome, stained with 5% uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and subsequently observed and captured using a Zeiss CEM-990 transmission electron microscope.

2.4. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA).

The isolated EVs were appropriately diluted and subjected to NTA using a NanoSight NS300 instrument manufactured by Malvern Panalytical Ltd. The NTA analysis was performed with a specific set of parameters to ensure accurate and reliable measurements. The NanoSight NS300 instrument was equipped with a sCMOS camera and operated at a wavelength of 532 nm. The camera level was set to auto, allowing for optimal adjustment of the camera's sensitivity to capture EVs with high resolution. The detection threshold was set to 10, ensuring that only particles above this threshold were considered for analysis. Manual focus adjustment was performed to achieve clear imaging of the EVs during the tracking process. For the NTA analysis, a volume of 500 µL of the isolated EVs sample was manually injected into the laser chamber of the NanoSight NS300 instrument. The injection was carefully carried out to prevent any introduction of air bubbles, or sample loss. Readings were taken in triplicate for each sample, with each reading lasting 30 seconds at a frame rate of 25 frames per second. This allowed for the tracking and measurement of EVs in real-time, capturing their Brownian motion.

2.5. Chemiluminescent Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (CL-ELISA) for the Detection of α-Gal, TS, and Parasite Membrane Molecules on EVs from Human Plasma from Healthy Individuals (controls) and Patients.

EVs (103particles/well) were analyzed using a CL-ELISA to detect specific antigens related to Chagas disease. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-α-Gal (human polyclonal antibody), anti-TS (mouse monoclonal antibody), and anti-T. cruzi membrane antibodies (rabbit polyclonal antibody). To perform the CL-ELISA, 96-well plates were coated with the isolated EVs and incubated overnight to ensure proper immobilization of the antigens. The plates were then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any unbound material. Subsequently, the wells were blocked for 1 hour using 5% non-fat dried milk to minimize non-specific binding and reduce background noise. After the blocking step, the plates were washed again with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, a detergent used to enhance the efficiency of washing and reduce non-specific interactions. Following the washes, the plates were incubated for 1 hour with the primary antibodies at appropriate dilutions. The anti-α-Gal antibody was diluted at 1:800, the anti-T. cruzi membrane antibody at 1:1000, and the anti-TS antibody at 1:1000. These primary anti-bodies specifically target the α-Gal epitope, T. cruzi membrane proteins, and TS antigens, respectively, enabling the detection of relevant markers associated with Chagas disease. In parallel, after washing with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, the plates were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour. The secondary antibodies, anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, and anti-human were diluted at 1:1000 and targeted the respective primary antibodies used in the assay. This step further amplified the signal generated by the specific antigen-antibody interactions. The plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 to remove any unbound secondary anti-bodies. Chemiluminescent substrate was added to the wells, and the plates were read at approximately 425 nm using an appropriate detection instrument. The chemiluminescent reaction generated light in proportion to the presence of the target antigens bound to the antibodies immobilized on the plate.

2.6. Data Analysis.

Data sets were compared using unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, and one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test, using GraphPad Prism 7 software. Differences in concentration and modal size of the EVs were analyzed by multiple comparisons and corrected for multiple testing (one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test), assuming values of p <0.05 to be significant as described earlier.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Patients with CCD and Controls

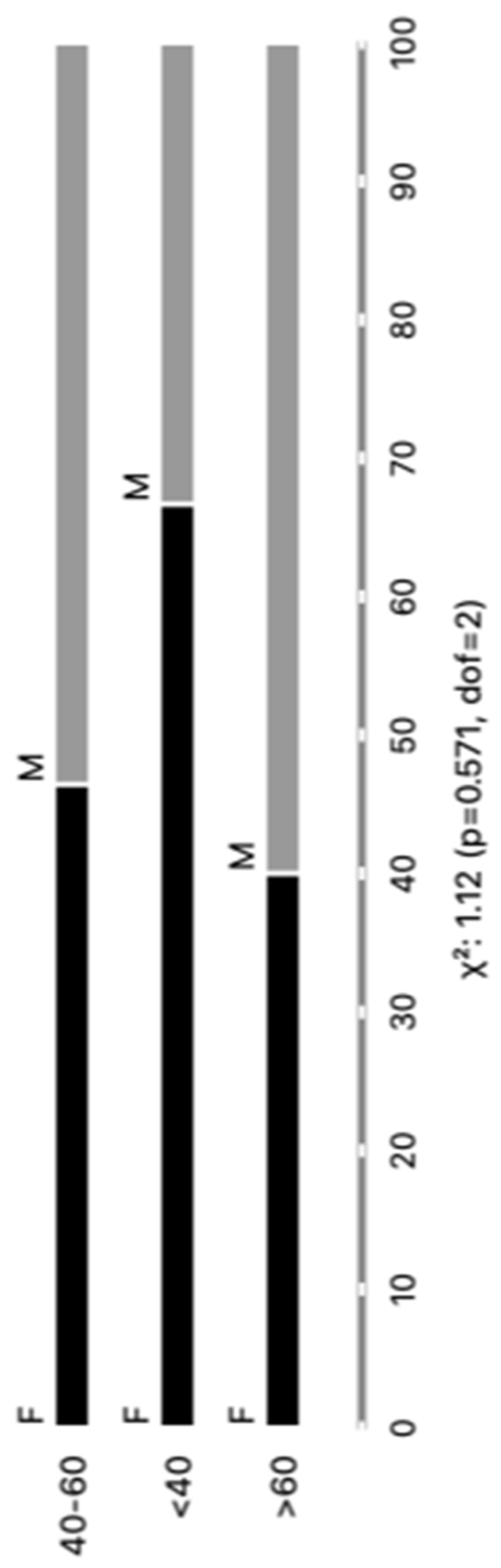

The distribution of the cohort of Chagas disease patients according to gender revealed a total of 44 individuals, with 23 (52%) being male and 21 (48%) being female. Regarding age groups, the patients were categorized as follows: 6 (14%) individuals were less than 40 years old, 28 (64%) fell between the ages of 40 and 60 years, and 10 (22%) were over 60 years old. No significant differences were observed in our analysis. We believe that our sample was carefully stratified, based on parasite detection results via PCR, as well as age and gender, thereby ensuring the representativeness of our results within the studied population. Every patient included in our study was undergoing a reactivation of the infection. Upon further analysis, where patients were categorized according to clinical forms and comorbidities, the subsequent outcomes emerged: Group I, comprising 24 (55%) patients, demonstrated an infection relapse primarily caused by immunosuppressive treatments following transplantation or cancer; Group II consisted of 16 (36%) patients diagnosed with chronic Chagas disease; finally, Group III included 4 (9%) patients with a co-infection of HIV and Chagas disease. These findings are graphically depicted in

Figure 1 and concisely summarized in Supplementary Table 1 and providing an inclusive perspective of the distribution of chronic Chagas disease reactivation across diverse patient demographics and clinical presentations. This control group was integrated into the study to function as a reference cohort for the purpose of comparing both age and sex demographics with the Chagasic patients' samples. The Healthy Controls (HC) group is meticulously characterized by both gender and age. In this cohort, there are 10 males and 20 females, total the 30 controls samples. The age distribution encompasses various categories, including individual; the HC with 20 years old (N=1); 20-39 years old (N=27); 40- to 59-year-old (N=2). This comparative strategy was employed to thoroughly scrutinize any observable discrepancies and to evaluate the potential ramifications of EVs markers.

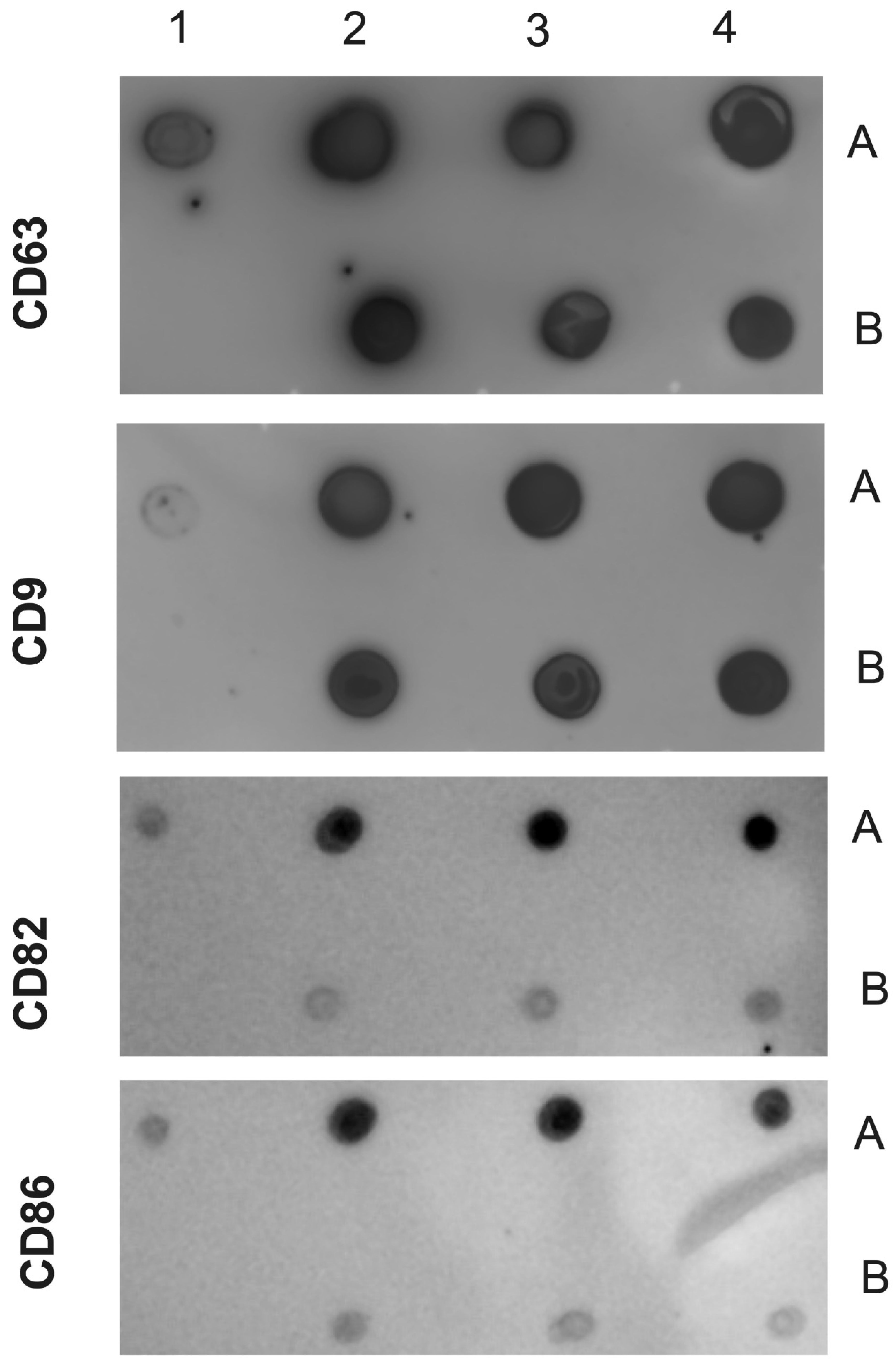

We are confident that there are no lipoproteins binding to

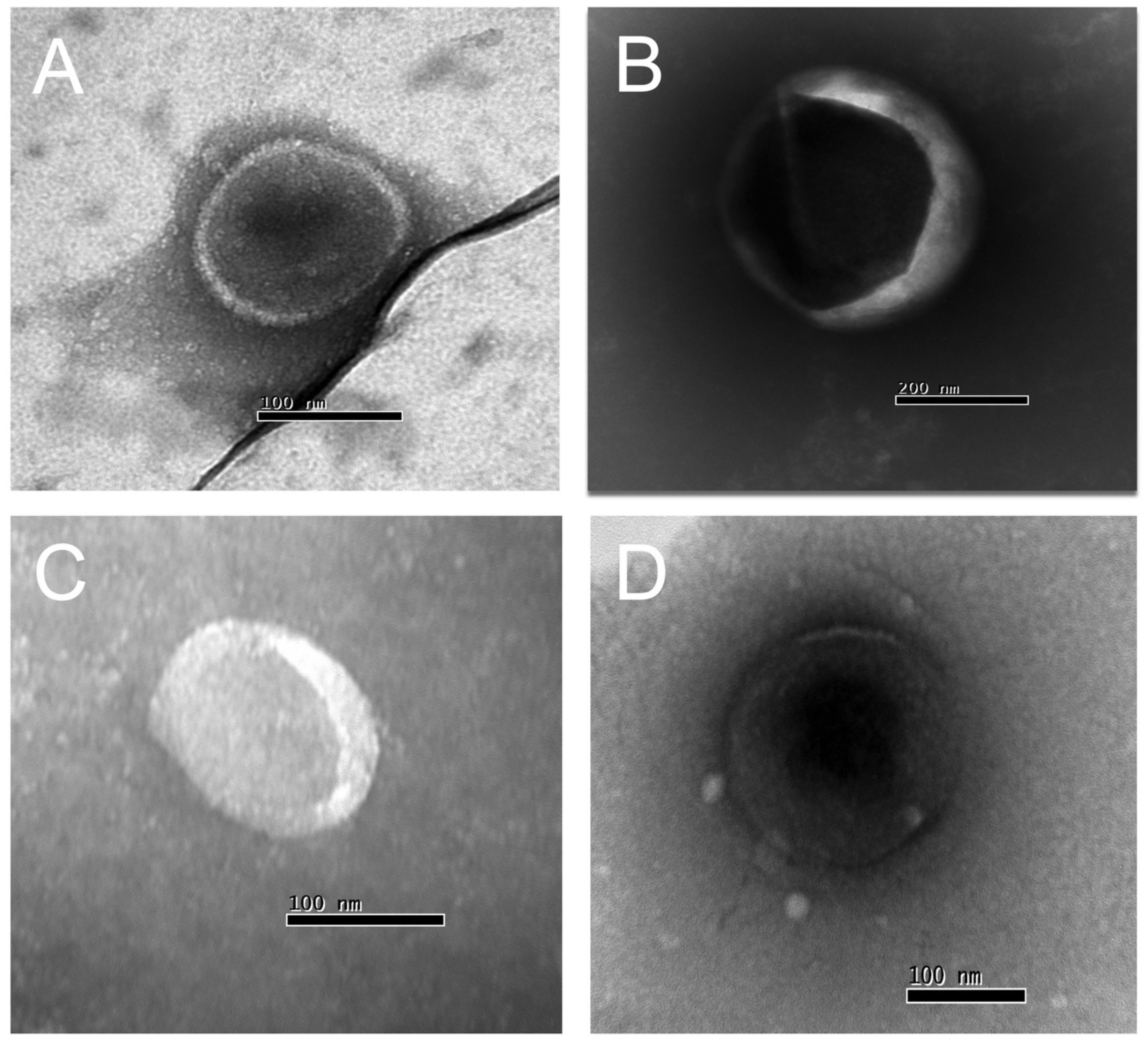

T. cruzi antigens present in the EVs after the purification of plasma particles from healthy people and patients using ultracentrifugation and Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), as we would not detect a positive response from specific antibodies to the parasite's glycoconjugates (there could be a detection block in the CL-ELISA). Additionally, we only used the fractions of the chromatography that were positive for EV markers like CD63, CD9, CD81, and CD82.The Dot Blot was then carried out using the same markers' EV. The parasite antigens were detected by the CL-ELISA assays with positive findings. Thus, the EV preparation is properly fractionated, purified, enriched, and characterized using SEC and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). According to

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, which shows representative samples of extracted and purified EVs from healthy people and patients, we performed Dot Blot using the primary EV markers. We are confident that there are no lipoproteins in the sample preparation, especially none that could interact with

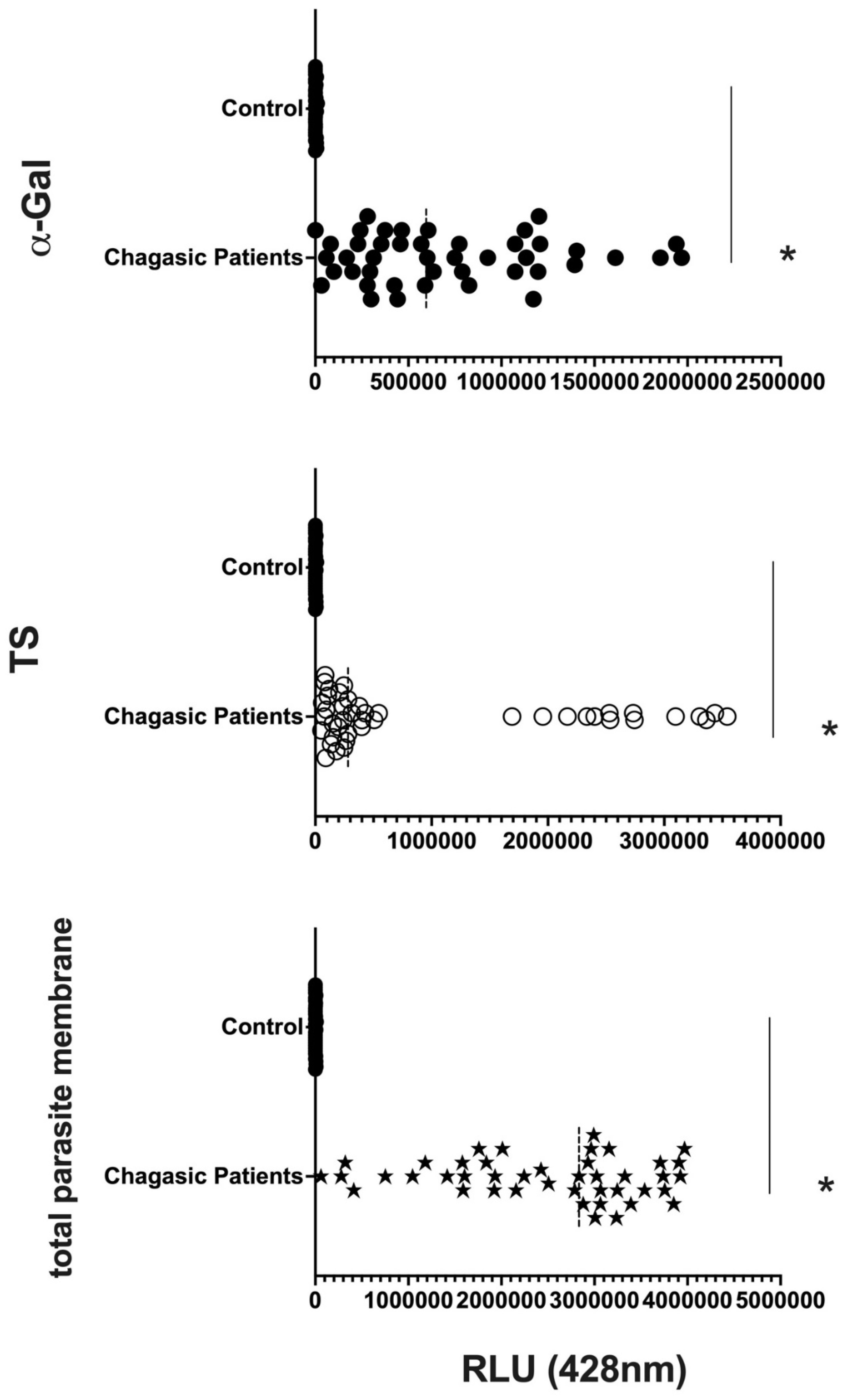

T. cruzi antigens. In parallel, we performed the CL-ELISA with EVs isolated from patients and heaths controls using antibodies against targeting the parasite plasma membrane, such as alpha-Gal and TS. The majority of antigenic epitopes expressed on the surface of the parasite's plasma membrane are recognized by these antibodies. All antibodies that target the parasite membrane and other parasite antigens recognized EVs isolated from chronic Chagas patients. In CL-ELISA, there is variation in the intensity of detection in the EVs samples from patients (

Figure 4). The detection threshold for EVs isolated from negative controls was less than 400 URL. As a result, we decided to conduct additional tests, stratifying the groups based on age, gender, and the cause of Chagas disease reactivation in patients.

3.2. EV Size Did Not Differ Much among Groups, But Clusters of Patients Can Be Observed.

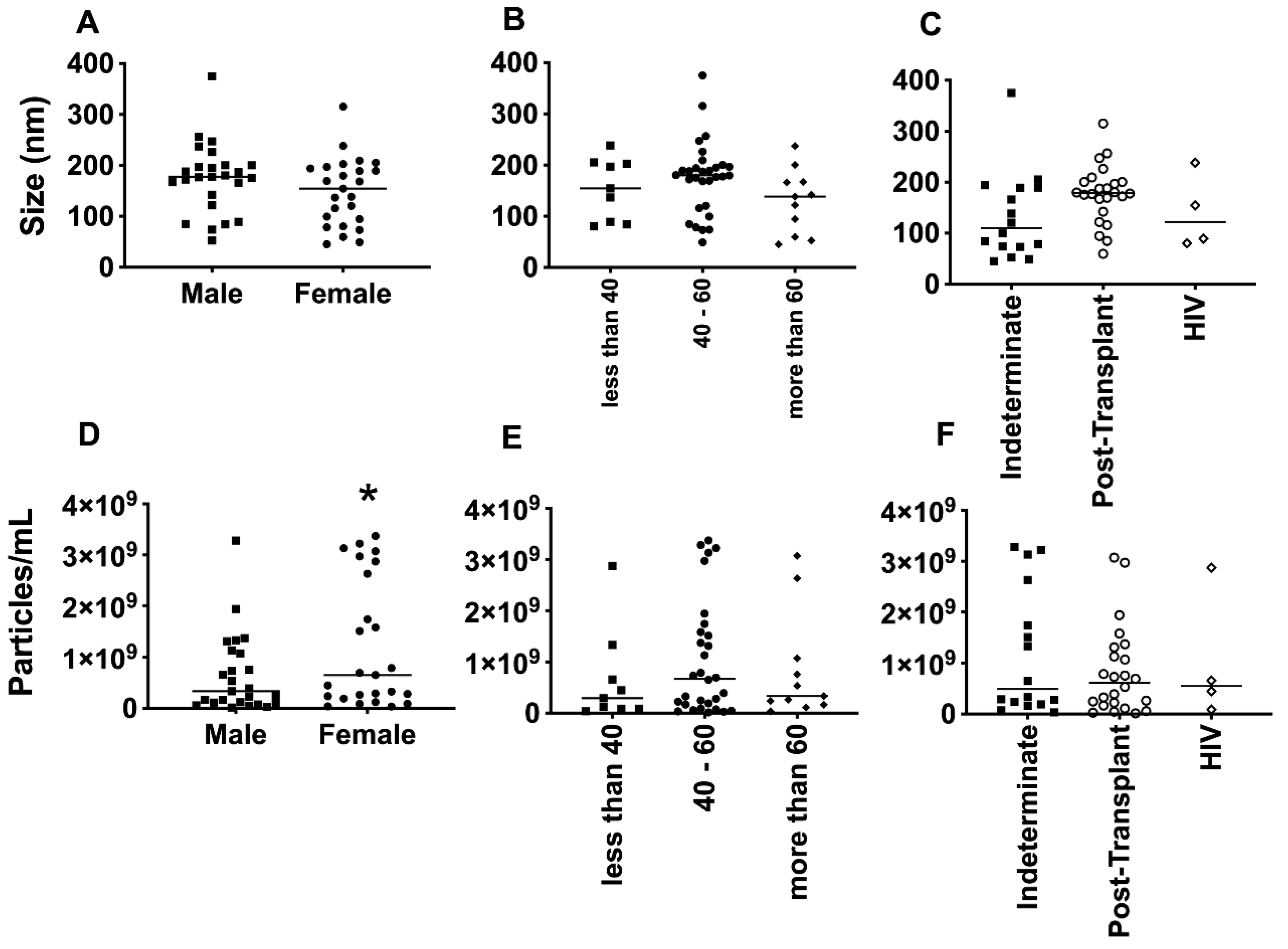

The average size of EVs purified from the plasma of patients with Chagas disease was approximately 150 nm, as determined by NTA (

Figure 5A–C). Interestingly, no significant differences in EV size were observed when considering factors such as age, gender, or the clinical manifestation of the disease. However, upon examining individual values and plotting them together, two distinct subpopulations of EVs emerged, based on their size: one with diameters of around 200 nm and another of around 100 nm. This phenomenon was particularly evident when patients were grouped by sex and age. Regarding the concentration of EVs from the plasma of Chagas disease patients, the mean values ranged from approximately 1 x 10

8 to 1 x 10

9 EVs/mL (

Figure 5D–F). Although the graphical representation indicated certain trends among the mean concentrations, no statistically significant differences were observed.

3.3. Differential Expression of Parasite Molecules Demonstrates Variability Across Distinct Age Groups and Immunosuppression Categories

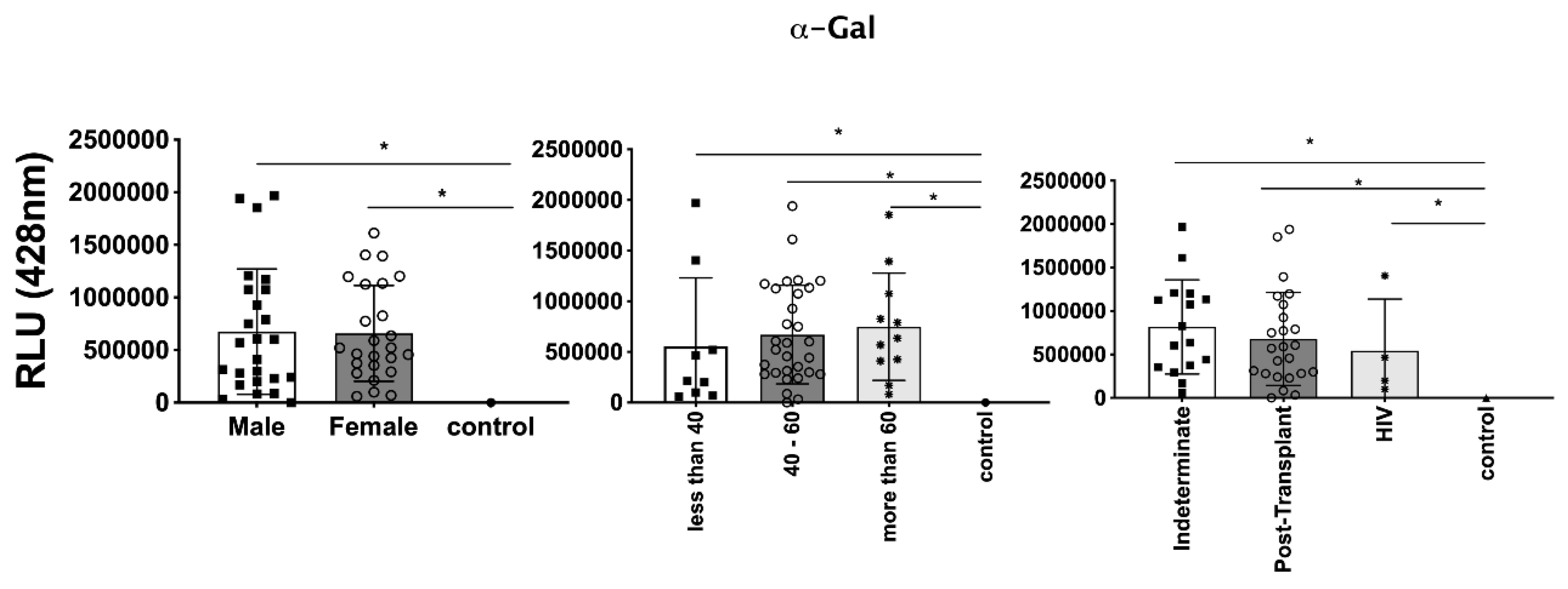

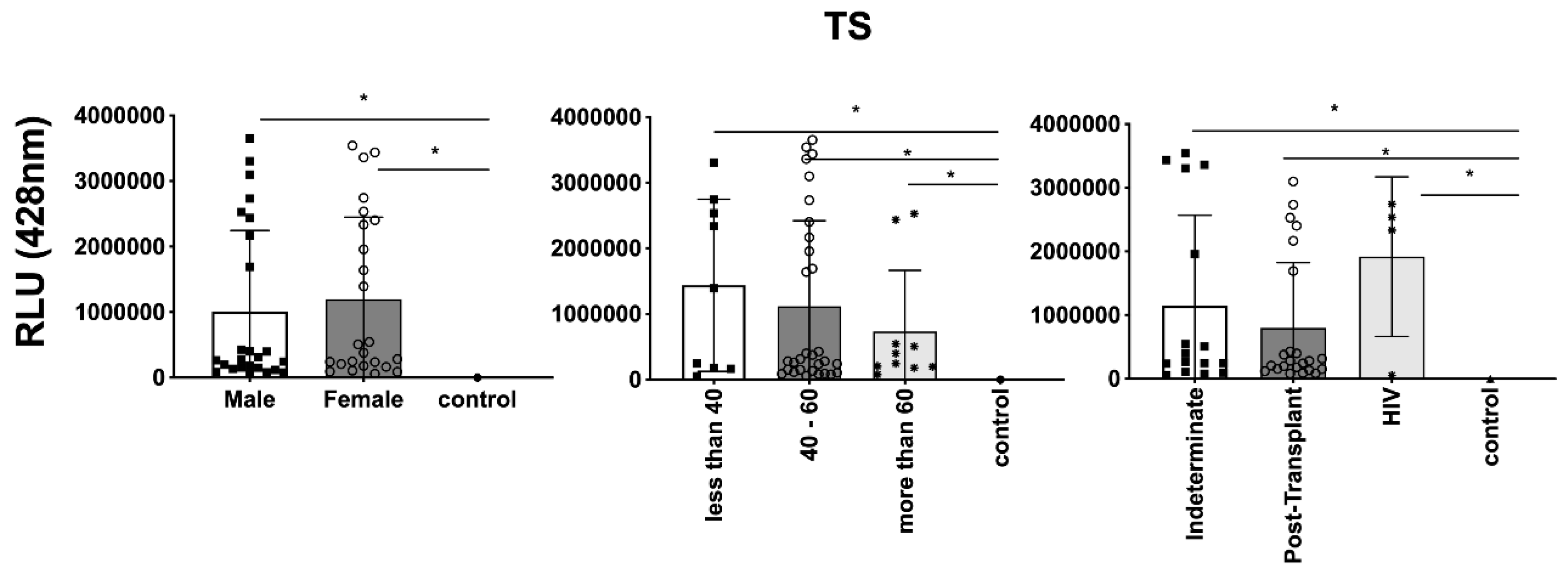

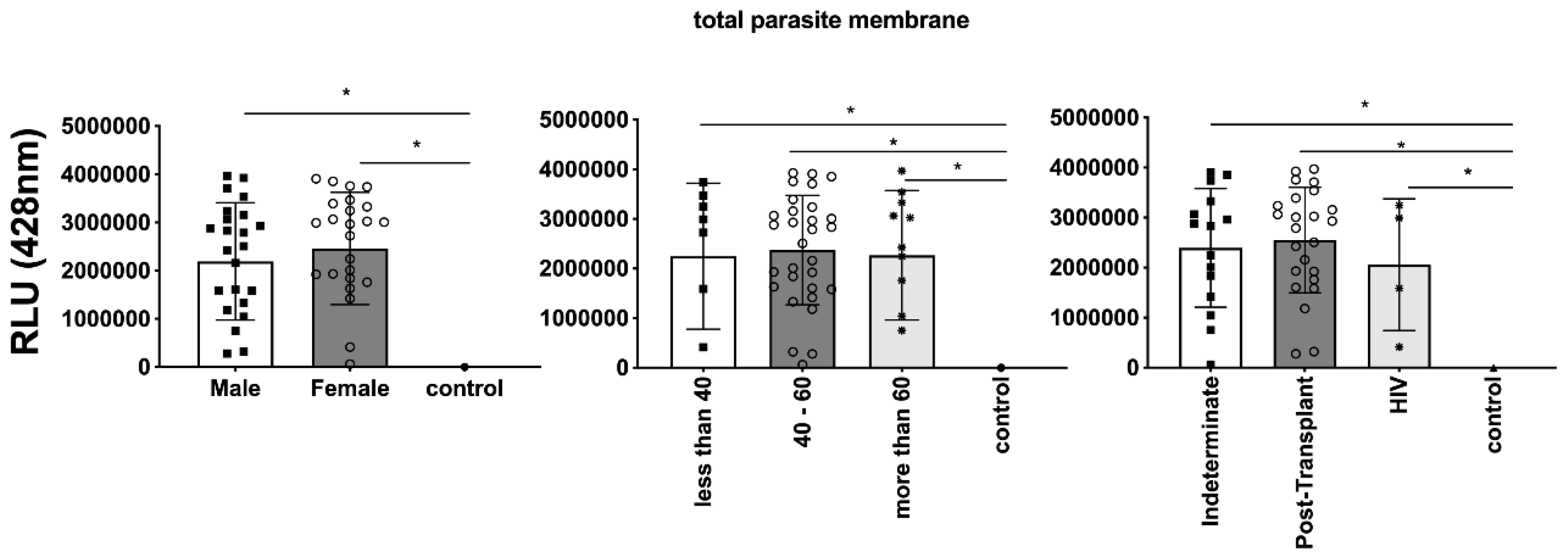

In parallel, we investigated the expression of

T. cruzi molecules in EVs derived from patient plasma. Three specific molecules, α-Gal present in the glycoproteins like mucin, TS, and total

T. cruzi membrane proteins, were analyzed. The results are displayed in:

Figure 6, representing α-Gal expression and detection;

Figure 7, TS expression/detection; and

Figure 8, illustrating the expression of total

T. cruzi membrane proteins. Remarkably, a considerable proportion of patients exhibited increased levels of α-Gal, particularly with advanced age, as depicted in

Figure 6. Conversely, TS expression was found to be low in these samples, as observed in

Figure 7. This phenomenon of TS expression was also observed when comparing immunosuppressed patients to non-immunosuppressed (indeterminate) Chagas patients (

Figure 7). Notably, clusters of patients were evident when analyzing TS expression (

Figure 7), similar to the observations in mean size analysis (

Figure 5). Gender did not appear to be a confounding factor on specific molecule expression. In addition, there were no differences among groups for total

T. cruzi membrane molecules (

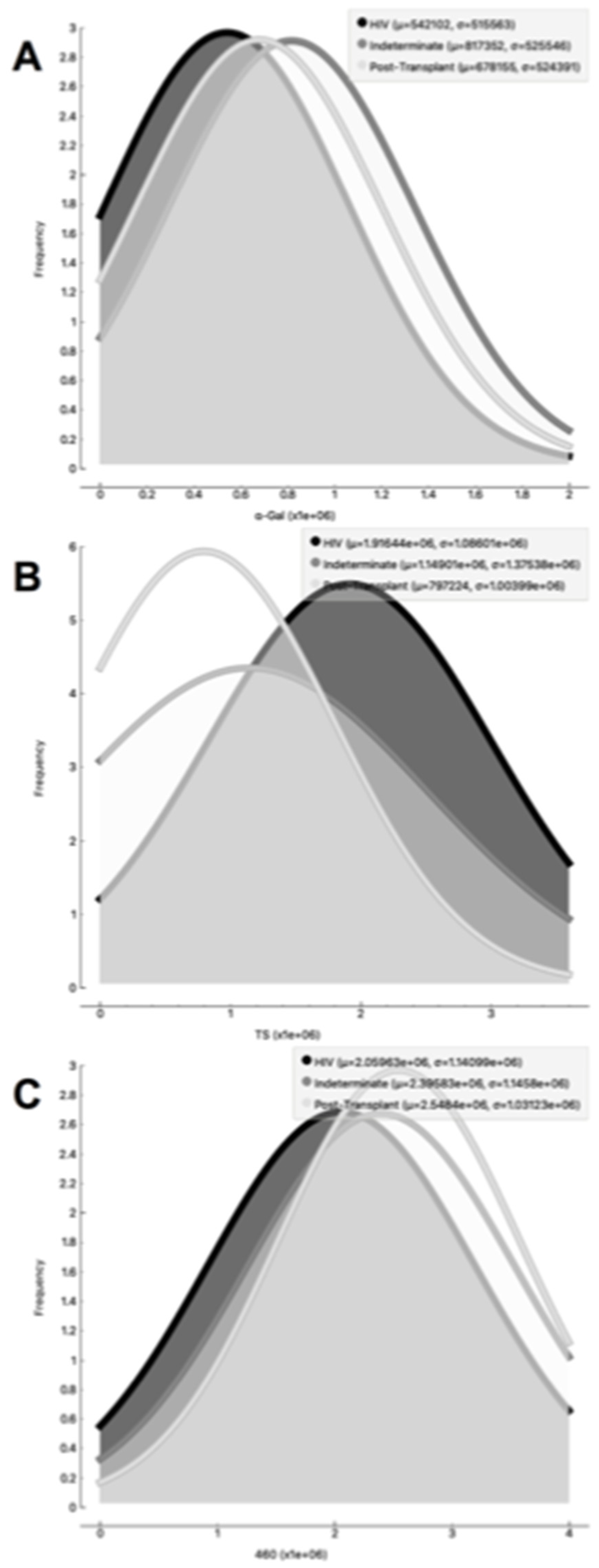

Figure 8). In the CL-ELISA assays, the control samples were EVs isolated from healthy donors. Notably, our results demonstrated a lack of reactivity in the EVs isolated from donors, thereby highlighting the assay's specificity for circulating EVs derived from chronic Chagasic patients. This specificity is particularly relevant in the context of patients experiencing recurrence of infection due to immunosuppressive treatment following transplantation or cancer. Moreover, statistically significant results were obtained when analyzing patients diagnosed with chronic Chagas disease and those with the co-infection of HIV and Chagas disease. Moreover, upon evaluating the frequency of immunosuppressed patients in relation to parasite molecule expression, it was found that there were no significant differences in the expression of αGal or total membrane proteins (

Figure 9A and 9B respectively). However, our data revealed a higher frequency of HIV-immunosuppressed patients with elevated expression of trans-sialidase (

Figure 9 B).

4. Discussion

In the last decade, the applications of EVs in clinical therapy have witnessed re-markable advancements (Soekmadji et al., 2020; Torrecilhas et al., 2012; Torrecilhas et al., 2020). However, despite the growing interest, several challenges persist in the clinical investigation of EVs, particularly regarding their utilization in clinical trials and their application in monitoring the progression of inflammatory and infectious diseases (Cortes-Serra et al., 2022; Cortes-Serra et al., 2020a; Cortes-Serra et al., 2020b). One major obstacle is the absence of reliable biomarkers for tracking the progression of infectious diseases. Animal models have demonstrated the significant involvement of EVs in the development of heart parasitism and inflammation during infection (Marcilla et al., 2014; Trocoli Torrecilhas et al., 2009). Taking inspiration from these findings, we aimed to characterize the circulating population of EVs in the peripheral blood of patients diag-nosed with chronic Chagas disease (CCD). Chagas disease, which is caused by the parasite T. cruzi, is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting millions of individuals worldwide. By studying the EVs in CCD patients, we aimed to gain insights into their composition, functions, and potential immunomodulatory capacities. To accomplish this, we designed an experimental approach involving both in vivo and in vitro investigations. First, we focused on analyzing the peripheral blood circulating population of EVs in CCD patients. We collected blood samples from a cohort of CCD patients and isolated EVs using established techniques such as ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography. The isolated EVs were then subjected to detailed characterization, including their size distribution, surface marker expression, cargo content, and subpopulation heterogeneity. This analysis aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of EV profiles in CCD patients, shedding light on their potential roles in disease pathogenesis and progression (Cortes-Serra et al., 2022; Cortes-Serra et al., 2020a; Madeira et al., 2021; Madeira et al., 2022). By characterizing EVs in CCD patients and evaluating their immunomodulatory potential, our study aimed to contribute to the understanding of pathogenesis and immune dynamics in Chagas disease (Marin-Neto et al., 2007; Ribeirao et al., 2000; Saraiva et al., 2021; Tanowitz et al., 2015; Torrecilhas et al., 2012; Torrecilhas et al., 2020; Vazquez-Chagoyan et al., 2011). The results obtained from our investigations have the potential to uncover new insights into the role of EVs in infectious diseases and pave the way for the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Ultimately, by harnessing the knowledge gained from studying EVs, we aim to advance the field of clinical therapeutics and improve patient outcomes in the context of inflammatory and infectious diseases.

An increase or decrease in the concentration of circulating extracellular vesicles (EVs) has been observed in various inflammatory and infectious processes (Cortes-Serra et al., 2022; Cortes-Serra et al., 2020a; Madeira et al., 2021; Madeira et al., 2022). For instance, patients with periodontitis exhibit increased EV concentrations in crevicular fluid, which correlates with clinical inflammatory parameters (Chaparro Padilla et al., 2020). In im-immunocompromised individuals, such as those with B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab, the ability to mount an appropriate immune response against pathogens is impaired, potentially leading to disease relapse even after achieving clinical cure (Reuken et al., 2021).

In our study, we observed a trend where female patients had higher concentrations of circulating EVs compared to male patients. This finding could be influenced by factors such as menstrual cycle stage, as women exhibit variable EV concentrations depending on the stage of their menstrual cycle. In addition, these differences tend to diminish with age (Bammert et al., 2017; Toth et al., 2007). It is worth noting that most of our patients below the age of 40 were women, which may contribute to the observed differences.

Glycoconjugates present on the parasite membrane play a crucial role in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of Chagas disease. The α-galactose epitopes, located on mucins anchored to the membrane by glycophosphatidylinositol, are highly immuno-genic and stimulate the production of lytic antibodies in Chagas disease patients (Almeida et al., 2000; Almeida et al., 1999; Almeida and Gazzinelli, 2001; Brito et al., 2016; Portillo et al., 2019). Another important parasite molecule involved in parasite-host interactions is the trans-sialidase enzyme, which plays a role in cell invasion, complement evasion, and induces IFN-γ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Ribeirao et al., 2000; Schenkman and Eichinger, 1993; Schenkman et al., 1994; Schenkman et al., 1993; Schenkman et al., 1992; Torrecilhas et al., 2012; Torrecilhas et al., 2020). In our studies with patients with disease reactivation, we detected the presence of both α-galactose and trans-sialidase, as well as other unidentified parasite proteins. Interestingly, our results showed a positive correlation for α-galactose and a negative correlation for trans-sialidase when stratifying our patient population by age. This was expected, as changes in immune response occur due to immunosenescence, the gradual decline of immune function with age (Wang et al., 2022).

Impairment of immune response development is also observed in patients under-going transplantation, such as liver transplant recipients, who have a higher risk of in-fection or reactivation of previous cytomegalovirus infections (Da Cunha and Wu, 2021). Furthermore, in vitro co-infection of astrocytes with T. cruzi and HIV leads to changes in the microenvironmental oxidative state, affecting parasite growth and development (Urquiza et al., 2020). Considering the variable protein expression observed in our pa-tients when stratified by immunosuppression, this altered immune response condition could be an important modifying factor, as it is not uncommon in these clinical settings.

In conclusion, the variations in α-galactose and trans-sialidase expression on EVs during acute disease reactivation may be associated with the modulation of immune responses in the chronic phase of Chagas disease. These findings highlight the complex interplay between immune response, parasite molecules and disease progression, emphasizing the need for further research to obtain a better understanding of these mechanisms and their implications for Chagas disease management.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: RPM, VLP-C and ACT. Per-formed most experiments: RPM, NL, PM and VLP-C. Wrote the manuscript: RPM, PM, and ACT. Contributed to final manuscript: RPM, VLP-C and ACT. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP): grant 2019/15909-0 and FAPESP 2020/07870-4 to ACT; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq): Grant 408186/2018-6 to ACT; and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES): Doctoral Fellowship (Financial Code 001) to RPM and PM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lucas Barros for performing the CL-ELISA, and all colleagues from Laboratório de Imunologia Celular & Bioquímica de fungos e protozoários (LICBfp) at the Departamento de Ciências Farmacêuticas, UNIFESP, who provided helpful technical advice and expertise that greatly assisted the research. We thank Prof Luiz R. Travassos for kindly providing the anti-α-Gal antibody, and Prof Sergio Schenkman for kindly providing the anti-TS and anti-T.cruzi membrane antibodies.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

List of Abbreviations

CCD Chronic Chagas Disease

CL-ELISA Chemiluminescent Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

DNA Deoxyribonucleic Acid

EDTA Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid

ELISA Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

EV Extracellular Vesicle

FAM Fluorescein Amine

GPI Glycosylphosphatidylinositol

HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HRP Horseradish Peroxidase

IFN-y Interferon gamma

MGB Minor Groove Binder

NFQ Nonfluorescent Quencher

NTA Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

PBS Phosphate Buffer Solution

PCR Polymerase Chain Reaction

qPCR Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

RLU Relative Light Units

T. cruzi Trypanosoma cruzi

TS Trans-sialidase

References

- Abras, A., C. Ballart, A. Fernandez-Arevalo, M.J. Pinazo, J. Gascon, C. Munoz, and M. Gallego. 2022. Worldwide Control and Management of Chagas Disease in a New Era of Globalization: A Close Look at Congenital Trypanosoma cruzi Infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 35: e0015221. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, I.C., M.M. Camargo, D.O. Procópio, L.S. Silva, A. Mehlert, L.R. Travassos, R.T. Gazzinelli, and M.A. Ferguson. 2000. Highly purified glycosylphosphatidylinositols from Trypanosoma cruzi are potent proinflammatory agents. EMBO J. 19:1476-1485. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, I.C., R. Gazzinelli, M.A. Ferguson, and L.R. Travassos. 1999. Trypanosoma cruzi mucins: potential functions of a complex structure. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 94 Suppl 1:173-176. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, I.C., and R.T. Gazzinelli. 2001. Proinflammatory activity of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors derived from Trypanosoma cruzi: structural and functional analyses. J Leukoc Biol. 70:467-477. [CrossRef]

- Angheben, A., L. Boix, D. Buonfrate, F. Gobbi, Z. Bisoffi, S. Pupella, G. Gandini, and G. Aprili. 2015. Chagas disease and transfusion medicine: a perspective from non-endemic countries. Blood Transfus. 13:540-550. [CrossRef]

- Assal, A., and C. Corbi. 2011. [Chagas disease and blood transfusion: an emerging issue in non-endemic countries]. Transfus Clin Biol. 18:286-291. [CrossRef]

- Bammert, T.D., J.G. Hijmans, P.J. Kavlich, G.M. Lincenberg, W.R. Reiakvam, R.T. Fay, J.J. Greiner, B.L. Stauffer, and C.A. DeSouza. 2017. Influence of sex on the number of circulating endothelial microparticles and microRNA expression in middle-aged adults. Exp Physiol. 102:894-900. [CrossRef]

- Bern, C. 2015. Chagas' Disease. N Engl J Med. 373:456-466. [CrossRef]

- Bocchi, E. 2018. Chagas disease cardiomyopathy treatment remains a challenge. Lancet. 391:2209. [CrossRef]

- Bonney, K.M., D.J. Luthringer, S.A. Kim, N.J. Garg, and D.M. Engman. 2019. Pathology and Pathogenesis of Chagas Heart Disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 14:421-447. [CrossRef]

- Brito, C.R., C.S. McKay, M.A. Azevedo, L.C. Santos, A.P. Venuto, D.F. Nunes, D.A. D'Avila, G.M. Rodrigues da Cunha, I.C. Almeida, R.T. Gazzinelli, L.M. Galvao, E. [CrossRef]

- Chiari, C.A. Sanhueza, M.G. Finn, and A.F. Marques. 2016. Virus-like Particle Display of the alpha-Gal Epitope for the Diagnostic Assessment of Chagas Disease. ACS Infect Dis. 2:917-922. [CrossRef]

- Camargo, M.M., I.C. Almeida, M.E. Pereira, M.A. Ferguson, L.R. Travassos, and R.T. Gazzinelli. 1997. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored mucin-like glycoproteins isolated from Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes initiate the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages. J Immunol. 158:5890-5901. [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.A., I.C. Almeida, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, E.P. Valente, D.O. Procópio, L.R. Travassos, J.A. Smith, D.T. Golenbock, and R.T. Gazzinelli. 2001. Activation of Toll-like receptor-2 by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from a protozoan parasite. J Immunol. 167:416-423. [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.A., G.M. Rosinha, I.C. Almeida, X.S. Salgueiro, B.W. Jarvis, G.A. Splitter, N. Qureshi, O. Bruna-Romero, R.T. Gazzinelli, and S.C. Oliveira. 2004. Role of Toll-like receptor 4 in induction of cell-mediated immunity and resistance to Brucella abortus infection in mice. Infect Immun. 72:176-186. [CrossRef]

- Chaparro Padilla, A., L. Weber Aracena, O. Realini Fuentes, D. Albers Busquetts, M. Hernandez Rios, V. Ramirez Lobos, A. Pascual La Rocca, J. Nart Molina, V. Beltran Varas, S. Acuna-Gallardo, and A. Sanz Ruiz. 2020. Molecular signatures of extracellular vesicles in oral fluids of periodontitis patients. Oral Dis. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M., G. Raposo, and C. Thery. 2014. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 30:255-289. [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Serra, N., M. Gualdron-Lopez, M.J. Pinazo, A.C. Torrecilhas, and C. Fernandez-Becerra. 2022. Extracellular Vesicles in Trypanosoma cruzi Infection: Immunomodulatory Effects and Future Perspectives as Potential Control Tools against Chagas Disease. J Immunol Res. 2022:5230603. [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Serra, N., I. Losada-Galvan, M.J. Pinazo, C. Fernandez-Becerra, J. Gascon, and J. Alonso-Padilla. 2020a. State-of-the-art in host-derived biomarkers of Chagas disease prognosis and early evaluation of anti-Trypanosoma cruzi treatment response. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1866:165758. [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Serra, N., M.T. Mendes, C. Mazagatos, J. Segui-Barber, C.C. Ellis, C. Ballart, A. Garcia-Alvarez, M. Gállego, J. Gascon, I.C. Almeida, M.J. Pinazo, and C. Fernandez-Becerra. 2020b. Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Potential Biomarkers in Heart Transplant Patient with Chronic Chagas Disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 26:1846-1851. [CrossRef]

- Coura, J.R., and P.A. Viñas. 2010. Chagas disease: a new worldwide challenge. Nature. 465: S6-7. [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, T., and G.Y. Wu. 2021. Cytomegalovirus Hepatitis in Immunocompetent and Immunocompromised Hosts. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 9:106-115. [CrossRef]

- De Fuentes-Vicente, J.A., N.G. Santos-Hernandez, C. Ruiz-Castillejos, E.E. Espinoza-Medinilla, A.L. Flores-Villegas, M. de Alba-Alvarado, M. Cabrera-Bravo, A. Moreno-Rodriguez, and D.G. Vidal-Lopez. 2023. What Do You Need to Know before Studying Chagas Disease? A Beginner's Guide. Trop Med Infect Dis. 8. [CrossRef]

- Gascon, J., C. Bern, and M.J. Pinazo. 2010. Chagas disease in Spain, the United States and other non-endemic countries. Acta Trop. 115:22-27. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Garcia, A., and J.A. Gilabert. 2023. Oral transmission of Chagas disease from a One Health approach: A systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. [CrossRef]

- Lotvall, J., A.F. Hill, F. Hochberg, E.I. Buzas, D. Di Vizio, C. Gardiner, Y.S. Gho, I.V. Kurochkin, S. Mathivanan, P. Quesenberry, S. Sahoo, H. Tahara, M.H. Wauben, K.W. Witwer, and C. Thery. 2014. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 3:26913. [CrossRef]

- Madeira, R.P., L.M. Dal'Mas Romera, P. de Cássia Buck, C. Mady, B.M. Ianni, and A.C. Torrecilhas. 2021. New Biomarker in Chagas Disease: Extracellular Vesicles Isolated from Peripheral Blood in Chronic Chagas Disease Patients Modulate the Human Immune Response. J Immunol Res. 2021:6650670. [CrossRef]

- Madeira, R.P., P. Meneghetti, L.A. de Barros, P. de Cassia Buck, C. Mady, B.M. Ianni, C. Fernandez-Becerra, and A.C. Torrecilhas. 2022. Isolation and molecular characterization of circulating extracellular vesicles from blood of chronic Chagas disease patients. Cell Biol Int. 46:883-894. [CrossRef]

- Malik, L. H., Singh, G. D., & Amsterdam, E. A. (2015). The epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management of chagas heart disease. Clinical Cardiology, 38(9), 565–569. [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A., L. Martin-Jaular, M. Trelis, A. de Menezes-Neto, A. Osuna, D. Bernal, C. Fernandez-Becerra, I.C. Almeida, and H.A. Del Portillo. 2014. Extracellular vesicles in parasitic diseases. J Extracell Vesicles. 3:25040. [CrossRef]

- Marin-Neto, J.A., E. Cunha-Neto, B.C. Maciel, and M.V. Simoes. 2007. Pathogenesis of chronic Chagas heart disease. Circulation. 115:1109-1123. [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.O., R.T. Souza, E.M. Cordero, D.C. Maldonado, C. Cortez, M.M. Marini, E.R. Ferreira, E. Bayer-Santos, I.C. Almeida, N. Yoshida, and J.F. Silveira. 2015. Molecular Characterization of a Novel Family of Trypanosoma cruzi Surface Membrane Proteins (TcSMP) Involved in Mammalian Host Cell Invasion. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 9:e0004216. [CrossRef]

- Monge-Maillo, B., and R. Lopez-Velez. 2017. Challenges in the management of Chagas disease in Latin-American migrants in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 23:290-295. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.C., V. Schmitz, E. Svensjo, R.T. Gazzinelli, I.C. Almeida, A. Todorov, L.B. de Arruda, A.C. Torrecilhas, J.B. Pesquero, A. Morrot, E. Bouskela, A. Bonomo, A.P. Lima, W. Müller-Esterl, and J. Scharfstein. 2006. Cooperative activation of TLR2 and bradykinin B2 receptor is required for induction of type 1 immunity in a mouse model of subcutaneous infection by Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 177:6325-6335. [CrossRef]

- Nakayasu, E.S., T.J. Sobreira, R. Torres, Jr., L. Ganiko, P.S. Oliveira, A.F. Marques, and I.C. Almeida. 2012. Improved proteomic approach for the discovery of potential vaccine targets in Trypanosoma cruzi. J Proteome Res. 11:237-246. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Molina, J.A., and I. Molina. 2018. Chagas disease cardiomyopathy treatment remains a challenge - Authors' reply. Lancet. 391:2209-2210. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Molina, J.A., A.M. Perez, F.F. Norman, B. Monge-Maillo, and R. Lopez-Velez. 2015. Old and new challenges in Chagas disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 15:1347-1356. [CrossRef]

- Porta, E.O.J., K. Kalesh, and P.G. Steel. 2023. Navigating drug repurposing for Chagas disease: advances, challenges, and opportunities. Front Pharmacol. 14:1233253. [CrossRef]

- Portillo, S., B.G. Zepeda, E. Iniguez, J.J. Olivas, N.H. Karimi, O.C. Moreira, A.F. Marques, K. Michael, R.A. Maldonado, and I.C. Almeida. 2019. A prophylactic alpha-Gal-based glycovaccine effectively protects against murine acute Chagas disease. NPJ Vaccines. 4:13. [CrossRef]

- Procópio, D.O., I.C. Almeida, A.C. Torrecilhas, J.E. Cardoso, L. Teyton, L.R. Travassos, A. Bendelac, and R.T. Gazzinelli. 2002. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored mucin-like glycoproteins from Trypanosoma cruzi bind to CD1d but do not elicit dominant innate or adaptive immune responses via the CD1d/NKT cell pathway. J Immunol. 169:3926-3933. [CrossRef]

- Rassi, A., Rassi, A., & Marin-Neto, J. A. 2010. Chagas disease. The Lancet, 375(9723), 1388–1402. [CrossRef]

- Reuken, P.A., A. Stallmach, M.W. Pletz, C. Brandt, N. Andreas, S. Hahnfeld, B. Loffler, S. Baumgart, T. Kamradt, and M. Bauer. 2021. Severe clinical relapse in an immunocompromised host with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection. Leukemia. 35:920-923. [CrossRef]

- Ribeirao, M., V.L. Pereira-Chioccola, L. Renia, A. Augusto Fragata Filho, S. Schenkman, and M.M. Rodrigues. 2000. Chagasic patients develop a type 1 immune response to Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase. Parasite Immunol. 22:49-53. [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, R.M., M.F.F. Mediano, F.S. Mendes, G.M. Sperandio da Silva, H.H. Veloso, L.H.C. Sangenis, P.S. da Silva, F. Mazzoli-Rocha, A.S. Sousa, M.T. Holanda, and A.M. Hasslocher-Moreno. 2021. Chagas heart disease: An overview of diagnosis, manifestations, treatment, and care. World J Cardiol. 13:654-675. [CrossRef]

- Steverding, D. 2014. The history of Chagas disease. In Parasites and Vectors (Vol. 7, Issue 1, p. 317). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Schenkman, S., and D. Eichinger. 1993. Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase and cell invasion. Parasitol Today. 9:218-222. [CrossRef]

- Schenkman, S., D. Eichinger, M.E. Pereira, and V. Nussenzweig. 1994. Structural and functional properties of Trypanosoma trans-sialidase. Annu Rev Microbiol. 48:499-523. [CrossRef]

- Schenkman, S., M.A. Ferguson, N. Heise, M.L. de Almeida, R.A. Mortara, and N. Yoshida. 1993. Mucin-like glycoproteins linked to the membrane by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor are the major acceptors of sialic acid in a reaction catalyzed by trans-sialidase in metacyclic forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 59:293-303. [CrossRef]

- Schenkman, S., T. Kurosaki, J.V. Ravetch, and V. Nussenzweig. 1992. Evidence for the participation of the Ssp-3 antigen in the invasion of nonphagocytic mammalian cells by Trypanosoma cruzi. J Exp Med. 175:1635-1641. [CrossRef]

- Shikanai-Yasuda, M.A., and N.B. Carvalho. 2012. Oral transmission of Chagas disease. Clin Infect Dis. 54:845-852. [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.P., P. Xander, A.O. Costa, A. Marcilla, A. Menezes-Neto, H. Del Portillo, K. Witwer, M. Wauben, E. Nolte-T Hoen, M. Olivier, M.F. Criado, L.L.P. da Silva, M.M. Abdel Baqui, S. Schenkman, W. Colli, M.J.M. Alves, K.S. Ferreira, R. Puccia, P. Nejsum, K. Riesbeck, A. Stensballe, E.P. Hansen, L.M. Jaular, R. Øvstebø, L. de la Canal, P. Bergese, V. Pereira-Chioccola, M.W. Pfaffl, J. Fritz, Y.S. Gho, and A.C. Torrecilhas. 2017. Highlights of the São Paulo ISEV workshop on extracellular vesicles in cross-kingdom communication. J Extracell Vesicles. 6:1407213. [CrossRef]

- Soekmadji, C., B. Li, Y. Huang, H. Wang, T. An, C. Liu, W. Pan, J. Chen, L. Cheung, J.M. Falcon-Perez, Y.S. Gho, H.B. Holthofer, M.T.N. Le, A. Marcilla, L. O'Driscoll, F. Shekari, T.L. Shen, A.C. Torrecilhas, X. Yan, F. Yang, H. Yin, Y. Xiao, Z. Zhao, X. Zou, Q. Wang, and L. Zheng. 2020. The future of Extracellular Vesicles as Theranostics - an ISEV meeting report. J Extracell Vesicles. 9:1809766. [CrossRef]

- Tanowitz, H.B., F.S. Machado, D.C. Spray, J.M. Friedman, O.S. Weiss, J.N. Lora, J. Nagajyothi, D.N. Moraes, N.J. Garg, M.C. Nunes, and A.L. Ribeiro. 2015. Developments in the management of Chagas cardiomyopathy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 13:1393-1409. [CrossRef]

- Théry, C., S. Amigorena, G. Raposo, and A. Clayton. 2006. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. Chapter 3: Unit 3.22. [CrossRef]

- Théry, C., M. Ostrowski, and E. Segura. 2009. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 9:581-593. [CrossRef]

- Théry, C., K.W. Witwer, E. Aikawa, M.J. Alcaraz, J.D. Anderson, R. Andriantsitohaina, A. Antoniou, T. Arab, F. Archer, G.K. Atkin-Smith, D.C. Ayre, J.M. Bach, D. Bachurski, H. Baharvand, L. Balaj, S. Baldacchino, N.N. Bauer, A.A. Baxter, M. Bebawy, C. Beckham, A. Bedina Zavec, A. Benmoussa, A.C. Berardi, P. Bergese, E. Bielska, C. Blenkiron, S. Bobis-Wozowicz, E. Boilard, W. Boireau, A. Bongiovanni, F.E. Borràs, S. Bosch, C.M. Boulanger, X. Breakefield, A.M. Breglio, M. Brennan, D.R. Brigstock, A. Brisson, M.L. Broekman, J.F. Bromberg, P. Bryl-Górecka, S. Buch, A.H. Buck, D. Burger, S. Busatto, D. Buschmann, B. Bussolati, E.I. Buzás, J.B. Byrd, G. Camussi, D.R. Carter, S. Caruso, L.W. Chamley, Y.T. Chang, C. Chen, S. Chen, L. Cheng, A.R. Chin, A. Clayton, S.P. Clerici, A. Cocks, E. Cocucci, R.J. Coffey, A. Cordeiro-da-Silva, Y. Couch, F.A. Coumans, B. Coyle, R. Crescitelli, M.F. Criado, C. D'Souza-Schorey, S. Das, A. Datta Chaudhuri, P. de Candia, E.F. De Santana, O. De Wever, H.A. Del Portillo, T. Demaret, S. Deville, A. Devitt, B. Dhondt, D. Di Vizio, L.C. Dieterich, V. Dolo, A.P. Dominguez Rubio, M. Dominici, M.R. Dourado, T.A. Driedonks, F.V. Duarte, H.M. Duncan, R.M. Eichenberger, K. Ekström, S. El Andaloussi, C. Elie-Caille, U. Erdbrügger, J.M. Falcón-Pérez, F. Fatima, J.E. Fish, M. Flores-Bellver, A. Försönits, A. Frelet-Barrand, et al. 2018. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 7:1535750. [CrossRef]

- Théry, C., L. Zitvogel, and S. Amigorena. 2002. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2:569-579. [CrossRef]

- Tkach, M., and C. Thery. 2016. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell. 164:1226-1232. [CrossRef]

- Torrecilhas, A.C., R.I. Schumacher, M.J. Alves, and W. Colli. 2012. Vesicles as carriers of virulence factors in parasitic protozoan diseases. Microbes Infect. 14:1465-1474. [CrossRef]

- Torrecilhas, A.C., R.P. Soares, S. Schenkman, C. Fernández-Prada, and M. Olivier. 2020. Extracellular Vesicles in Trypanosomatids: Host Cell Communication. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 10:602502. [CrossRef]

- Toth, B., K. Nikolajek, A. Rank, R. Nieuwland, P. Lohse, V. Pihusch, K. Friese, and C.J. Thaler. 2007. Gender-specific and menstrual cycle dependent differences in circulating microparticles. Platelets. 18:515-521. [CrossRef]

- Trocoli Torrecilhas, A.C., R.R. Tonelli, W.R. Pavanelli, J.S. da Silva, R.I. Schumacher, W. de Souza, N.C. E Silva, I. de Almeida Abrahamsohn, W. Colli, and M.J. Manso Alves. 2009. Trypanosoma cruzi: parasite shed vesicles increase heart parasitism and generate an intense inflammatory response. Microbes Infect. 11:29-39. [CrossRef]

- Urquiza, J., C. Cevallos, M.M. Elizalde, M.V. Delpino, and J. Quarleri. 2020. Priming Astrocytes With HIV-Induced Reactive Oxygen Species Enhances Their Trypanosoma cruzi Infection. Front Microbiol. 11:563320. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Chagoyan, J.C., S. Gupta, and N.J. Garg. 2011. Vaccine development against Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas disease. Adv Parasitol. 75:121-146. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., C. Dong, Y. Han, Z. Gu, and C. Sun. 2022. Immunosenescence, aging and successful aging. Front Immunol. 13:942796. [CrossRef]

- Steverding, D. (2014). The history of Chagas disease. In Parasites and Vectors (Vol. 7, Issue 1, p. 317). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Categorizing individuals with positive PCR results based on age and gender (M=male and F=female).

Figure 1.

Categorizing individuals with positive PCR results based on age and gender (M=male and F=female).

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of EVs isolated from Chagasic Chronic patients’ (A and B) and control health (C and D) (100-300 nm diameter).

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of EVs isolated from Chagasic Chronic patients’ (A and B) and control health (C and D) (100-300 nm diameter).

Figure 3.

Dot blot of EVs isolated from Chagasic Chronic patients and controls (healthy individuals). The following samples were spotted on the NM antibodies against CD63, CD9, CD82 and CD81. Positive control (1A) negative control (1B). EVs purified from Chagasic Chronic patients (2A, 3A and 4A) and EVs from Health control (2B, 3B and 4B). The MN were incubated with the indicated antibodies and revealed with the respective peroxidase conjugates.

Figure 3.

Dot blot of EVs isolated from Chagasic Chronic patients and controls (healthy individuals). The following samples were spotted on the NM antibodies against CD63, CD9, CD82 and CD81. Positive control (1A) negative control (1B). EVs purified from Chagasic Chronic patients (2A, 3A and 4A) and EVs from Health control (2B, 3B and 4B). The MN were incubated with the indicated antibodies and revealed with the respective peroxidase conjugates.

Figure 4.

Detection of expression of total membrane, α-Gal and TS epitopes in all EVs samples from Chagasic Chronic patients (PCR-positive individuals with CCD) and EVs isolated from control Heaths, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU). * The calculated p-value of the statistical analysis was less than 0.05, signifying the statistical significance of the outcomes.

Figure 4.

Detection of expression of total membrane, α-Gal and TS epitopes in all EVs samples from Chagasic Chronic patients (PCR-positive individuals with CCD) and EVs isolated from control Heaths, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU). * The calculated p-value of the statistical analysis was less than 0.05, signifying the statistical significance of the outcomes.

Figure 5.

Determination of the average size, in nanometers (5A, 5B, and 5C), and average concentration, in particles per milliliter (5D, 5E, and 5F), of EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD. Categorization based on gender (5A and 5D), age (5B and 5E), and immunosuppression status (5C and 5F). The "Indeterminate" group refers to immuno-competent chronic Chagas disease patients. * The p-value obtained from statistical analysis was less than 0.05, indicating that the results were statistically significant.

Figure 5.

Determination of the average size, in nanometers (5A, 5B, and 5C), and average concentration, in particles per milliliter (5D, 5E, and 5F), of EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD. Categorization based on gender (5A and 5D), age (5B and 5E), and immunosuppression status (5C and 5F). The "Indeterminate" group refers to immuno-competent chronic Chagas disease patients. * The p-value obtained from statistical analysis was less than 0.05, indicating that the results were statistically significant.

Figure 6.

Detection of expression of α-Gal epitopes in EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD and control, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU). Categorization based on gender (3A), age (3B), and immunosuppression status (3C). The "Indeterminate" group refers to immunocompetent CCD patients. The control group consisted of healthy individuals. * The calculated p-value of the statistical analysis was less than 0.05, signifying the statistical significance of the outcomes.

Figure 6.

Detection of expression of α-Gal epitopes in EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD and control, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU). Categorization based on gender (3A), age (3B), and immunosuppression status (3C). The "Indeterminate" group refers to immunocompetent CCD patients. The control group consisted of healthy individuals. * The calculated p-value of the statistical analysis was less than 0.05, signifying the statistical significance of the outcomes.

Figure 7.

Detection of Expression of TS in EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD and control, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU). Categorization based on gender (4A), age (4B), and immunosuppression status (4C). The "Indeterminate" group refers to immunocompetent CCD patients. The control group consisted of healthy individuals. * The calculated p-value of the statistical analysis was less than 0.05, signifying the statistical significance of the outcomes.

Figure 7.

Detection of Expression of TS in EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD and control, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU). Categorization based on gender (4A), age (4B), and immunosuppression status (4C). The "Indeterminate" group refers to immunocompetent CCD patients. The control group consisted of healthy individuals. * The calculated p-value of the statistical analysis was less than 0.05, signifying the statistical significance of the outcomes.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the expression of total parasite membrane in EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD and control, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU). Categorization based on gender (5A), age (5B), and immunosuppression status (5C). The "Indeterminate" group refers to immuno-competent CCD patients. The control group consisted of healthy individuals. * The calculated p-value of the statistical analysis was less than 0.05, signifying the statistical significance of the outcomes.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the expression of total parasite membrane in EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD and control, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU). Categorization based on gender (5A), age (5B), and immunosuppression status (5C). The "Indeterminate" group refers to immuno-competent CCD patients. The control group consisted of healthy individuals. * The calculated p-value of the statistical analysis was less than 0.05, signifying the statistical significance of the outcomes.

Figure 9.

Examination of the occurrence rate, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU), of α-Gal epitopes (9A), trans-sialidase epitopes (9B), and other parasite membrane epitopes (9C) in EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD. The data are presented using different lines: the black line represents individuals with HIV, the dark grey line represents the Indeterminate group, and the light grey line represents post-transplant patients.

Figure 9.

Examination of the occurrence rate, measured in Relative Light Units (RLU), of α-Gal epitopes (9A), trans-sialidase epitopes (9B), and other parasite membrane epitopes (9C) in EVs from PCR-positive individuals with CCD. The data are presented using different lines: the black line represents individuals with HIV, the dark grey line represents the Indeterminate group, and the light grey line represents post-transplant patients.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).