INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND OF STUDY

Nigeria's government officially announced the suspension of Twitter operations in the country on June 4th, 2021, which led to mobile phone networks blocking access to the microblogging platform. The tweet was analogized to the 1960’s Nigerian Civil War (Akresh et al. 2012). This decision was made two days after the microblogging and social media platform Twitter deleted the Nigerian President 1967 - 1970 Nigeria Civil War tweet saying “Many of those misbehaving today are too young to be aware of the destruction and loss of lives that occurred during the Nigerian Civil War. Those of us in the fields for 30 months, who went through the war, will treat them in the language they understand.” This post was seen as an “expressing intentions of self-harm or suicide” in line with the platform usage policy (Njoku et al. 2021), towards a secessionist movement in the south-east region of the country, leading to a rise in the country's Twitter space with widespread condemnation and criticism, Several Nigerians flagged the particular post and Twitter took it down on the premise of violation of its policy on abusive behaviour.

Following the ban development, the Minister of Information and Culture, Lai Mohammed reiterated and emphasised the platform's double standard about the President's deleted post on the Twitter handle, that it has never deleted similar inciting tweets from individuals, separatist leaders and, groups; heightened the display of biases to what the social platform did during #EndSARS in 2020 (Eze et al. 2021).

This steered a viral trend on the platform #ThankGodForVPN a day after effecting the ban on Saturday, June 5th 2021, in which the platform user celebrated their ability to bypass the platform ban with the use of virtual private networks (VPN).

After the ban, The Minister for Justice and Attorney-General of the Federation Abubakar Malami SAN mandated his ministry to prosecute any offender of the Federal Government ban on Twitter operations in Nigeria (Okonofua, 2021), This mandate targetted citizens and organisations (Public and Private Sector).

THE OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY

This study aims to comprehensively examine the frequency and awareness of the use of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) and Twitter among Nigerians during the 2021 ban, with a specific focus on investigating the impact of VPN usage. The broad objective is to shed light on the multifaceted dimensions of online communication and circumvention strategies during the Twitter ban. Specifically, the study seeks to address the following key questions:

What is the frequency of Twitter usage among Nigerians before and during the 2021 Twitter ban?

What specific brands of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) were predominantly used among Nigerians before and during the 2021 Twitter ban?

What is the level of awareness, knowledge, and satisfaction regarding Virtual Private Networks (VPN) among Nigerians before and during the 2021 Twitter ban?

What is the gender and age range distribution of social media users in Nigeria, particularly concerning Twitter, and how did this demographic composition evolve during the Twitter ban?

STATEMENT OF PROBLEM

Following the Nigerian government's decision to suspend Twitter operations indefinitely and the subsequent blocking of access to the platform by mobile phone network providers, Nigerians resorted to Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) as a means to conceal their IP addresses. This action effectively kept internet service providers (ISPs) unaware of their online activities and locations. The consequence of this shift was a remarkable 100% increase in VPN searches on Google within 24 hours, underscoring the swift and widespread adoption of VPNs by Nigerians during the ban (Google Trends).

While there have been numerous studies addressing the Nigeria Twitter ban, a critical gap remains in the understanding of the impact of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) on Nigerians during the 2021 Twitter ban. Existing research has largely focused on the ban's political, social, and economic implications, leaving unexplored the nuanced dynamics of VPN usage and its consequences on digital communication and information access.

To date, there has been a shortage of empirical evidence and scholarly inquiry into the motivations, experiences, and outcomes associated with the surge in VPN adoption during the Twitter ban. This research seeks to bridge this gap by investigating the multifaceted dimensions of VPN utilization and examining its implications for online privacy, information access, and digital communication among Nigerian users.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM):

Development and Background:

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) was developed by Fred Davis in 1989. TAM represents a significant theoretical framework in the realm of technology adoption, focusing on the factors that influence users' decisions to accept and use new technologies.

Key Tenets:

TAM centres around two critical factors - perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. According to this model, users are more likely to adopt and continue using a technology if they perceive it as easy to use and find it useful in fulfilling their needs.

Application in the Research Context:

In the context of the Twitter ban in Nigeria, TAM proves to be a pertinent theoretical framework. By employing TAM, the research seeks to analyze the adoption of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) during the ban. The model's emphasis on perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness allows for a comprehensive examination of the factors that influenced individuals to resort to VPNs as a workaround during the Twitter ban.

METHODOLOGY

In this research, the survey research method was chosen as the most fitting approach for examining the frequency and awareness of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and Twitter usage among Nigerians during the 2021 Twitter ban. The survey method allowed for the systematic collection, analysis, and evaluation of data, utilizing questionnaires as the principal instrument for data gathering. This approach was deemed appropriate due to its effectiveness in capturing public opinion, attitudes, and orientations within a large and diverse population over a specific timeframe (Nyekwere et al., 2014).

The study encompassed a sample size of 400 respondents strategically selected from various states across Nigeria to ensure a comprehensive representation of diverse perspectives. The sampling technique utilized was a stratified random sampling method, taking into account demographic variables such as age, gender, and geographical location. This approach aimed to enhance the generalizability of findings to the broader Nigerian population.

The self-administered and standard structured questionnaire employed in the survey comprised a mix of open-ended and close-ended questions, ensuring a nuanced exploration of respondents' experiences and perspectives. To cater to diverse connectivity situations, both online-based and offline-based data collection methods were employed. Online surveys were facilitated through platforms such as Google Forms, while offline surveys utilized tools like ODK Collect.

Recognizing the need for a more in-depth understanding of respondents' experiences, a qualitative component was integrated into the research design. This involved conducting interviews and focus group discussions, allowing for the exploration of nuanced perspectives related to VPN usage and Twitter engagement during the ban. The qualitative data was analyzed thematically to complement the quantitative findings (Wimmer & Dominick, 2011).

To ensure the reliability of the research instrument, a reliability analysis was conducted. Cronbach’s coefficient alphas were computed for each dimension of the questionnaire, demonstrating a good standard of reliability with values ranging from 0.627 to 0.816. These values exceeded the acceptable lower limit of 0.60, as recommended by Nunnally et al. (1994).

To bolster the robustness and validity of the study's findings, Pearson Correlation testing was employed. This statistical analysis was instrumental in examining relationships between variables, including the significant relationship between Twitter usage before and during the ban, as well as the correlation between the frequency of Twitter use and the duration of usage.

DATA ANALYSIS, INTERPRETATIONS AND DISCUSSION

The focus of this chapter is on the presentation and analysis of the data generated from the questionnaires administered, by four hundred (400) members of Twitter in Nigeria. 400 questionnaires were given out and were retrieved. Also, tables, figures and other common descriptive statistics and inferential statistics were used in presenting and analyzing the data collected.

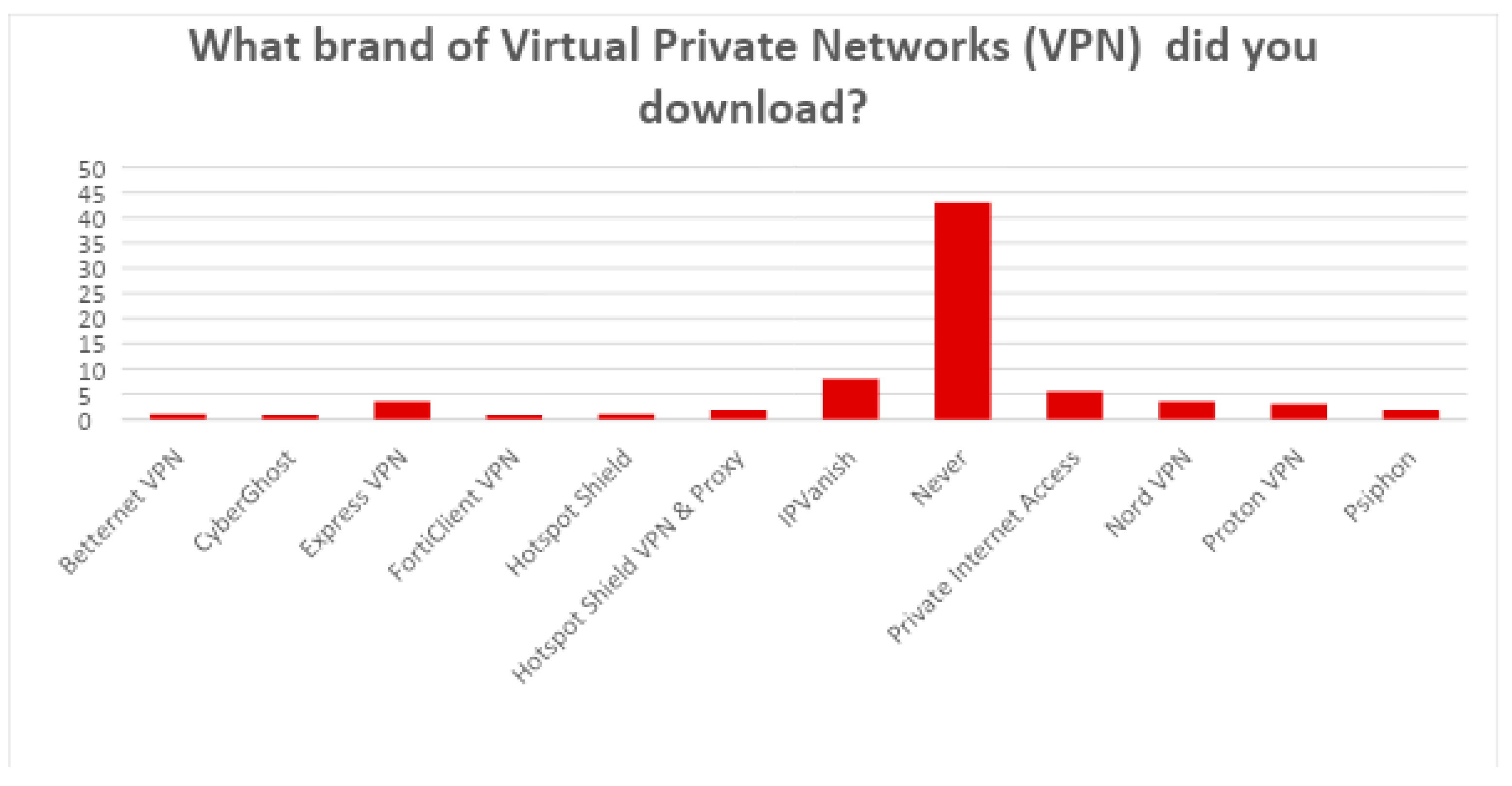

Figure 1.

Showing what brand of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) respondents used to download.

Figure 1.

Showing what brand of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) respondents used to download.

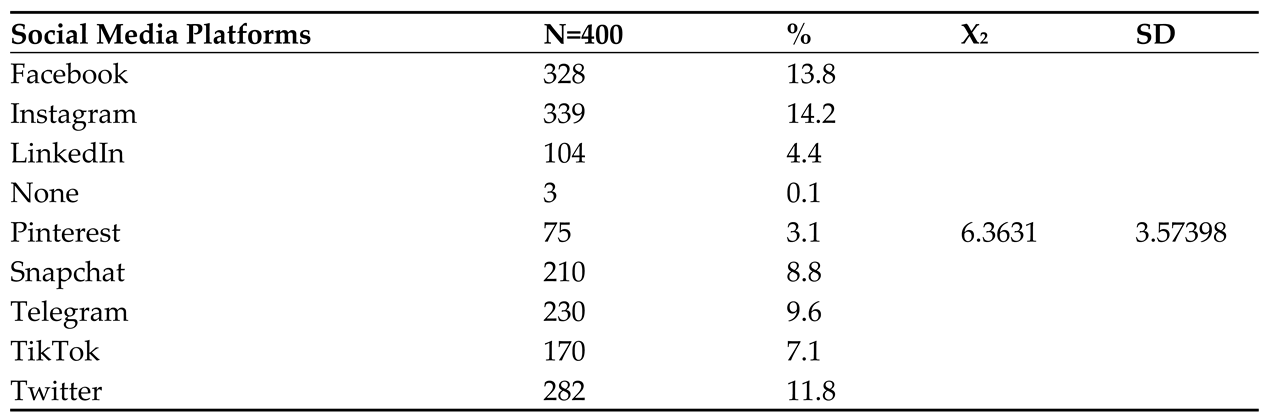

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of ‘which Social Media Platform do you use’?

Table 1 below shows the social media platform the Nigerian citizens use to access Twitter. The demographic profile of the respondents indicates a critical sample composition, a total of 400 respondents participated in this research with multiple responses. The result of the respondents shows that 328 respondents used Facebook, 339 respondents used Instagram, 104 respondents preferred LinkedIn as a social media, 3 chose none, 75 indicated Pinterest 210 respondents chose Snapchat as the most preferred social media platform, also, 230 respondents were using Telegram, 230 respondents use Tiktok and 282 respondents uses Twitter as the most preferred social media platform. However, the breakdown of the result showed that the majority of the respondents use Instagram with the highest number frequency number of 339, while Facebook has 328 users.

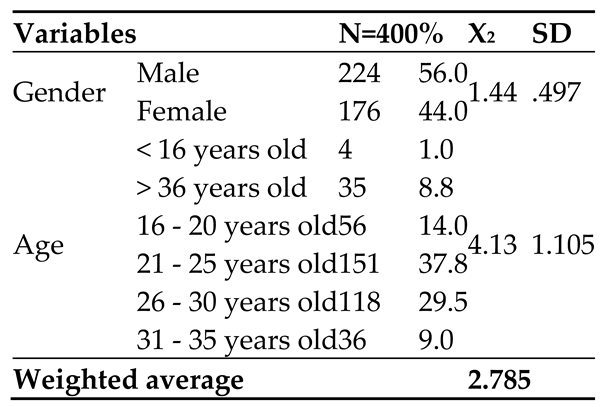

Table 2 below gives a response to respondent’s social demographic respondents. The result showed that 224 respondents were male while 176 respondents were female. Also, < 16 years old respondents were 4, 35 of the respondents were > 36 years old, 56 respondents were between age 16 - 20 years old, 151 of the respondents were between the age range of 21 - 25 years old, moreso, 118 of the respondents were within 26 - 30 years old and 36 of the respondents were between the age range of 31 - 35 years old. However, the result depicts that the highest number of people who participated in the research were within the age of 21-25 years old.

Moreso, the mean values for socio-economic characteristics which are gender and age were 1.44 and 4.13 respectively showing that gender value is lower than the weighted mean while age value is higher than the weighted mean.

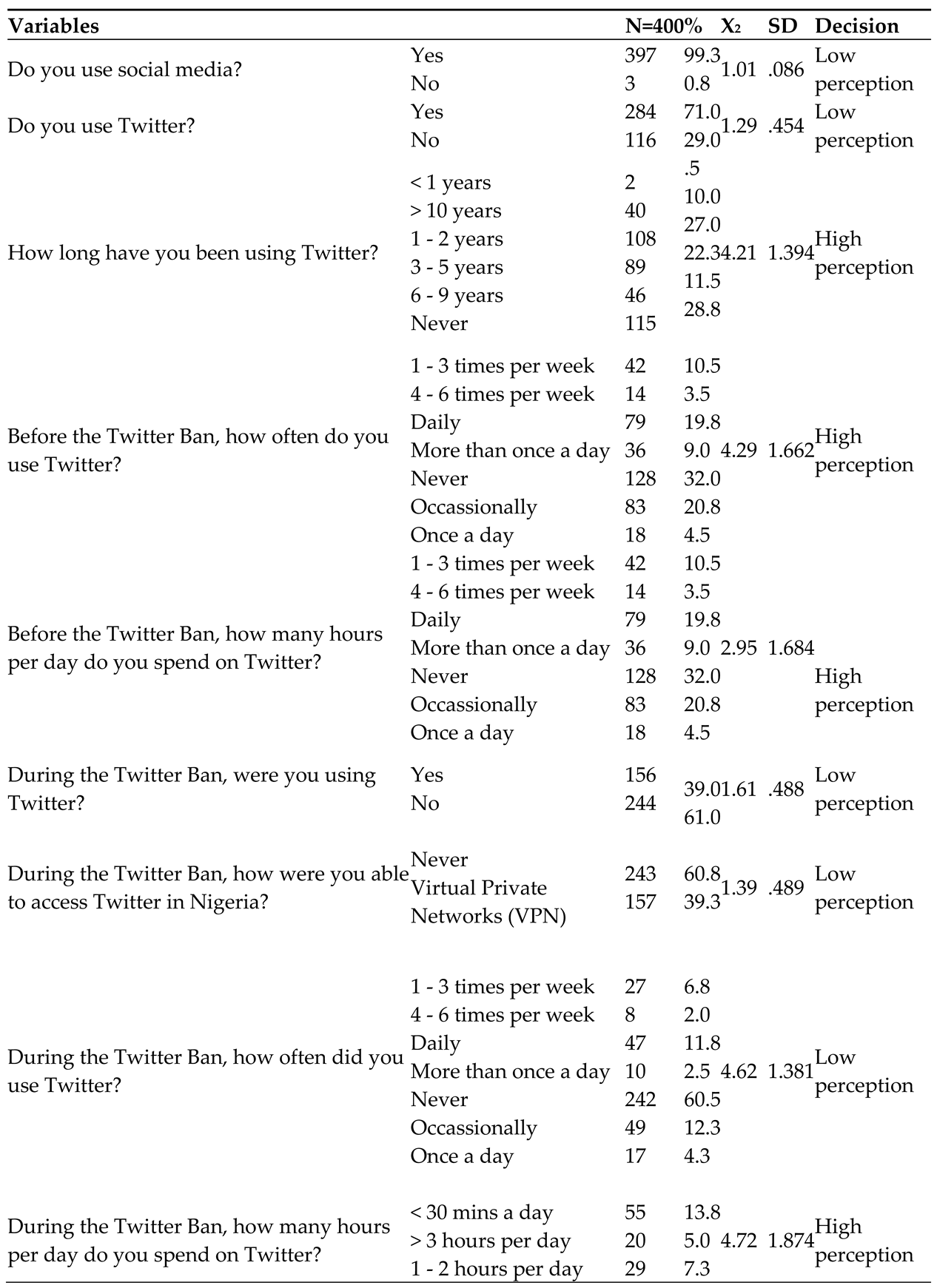

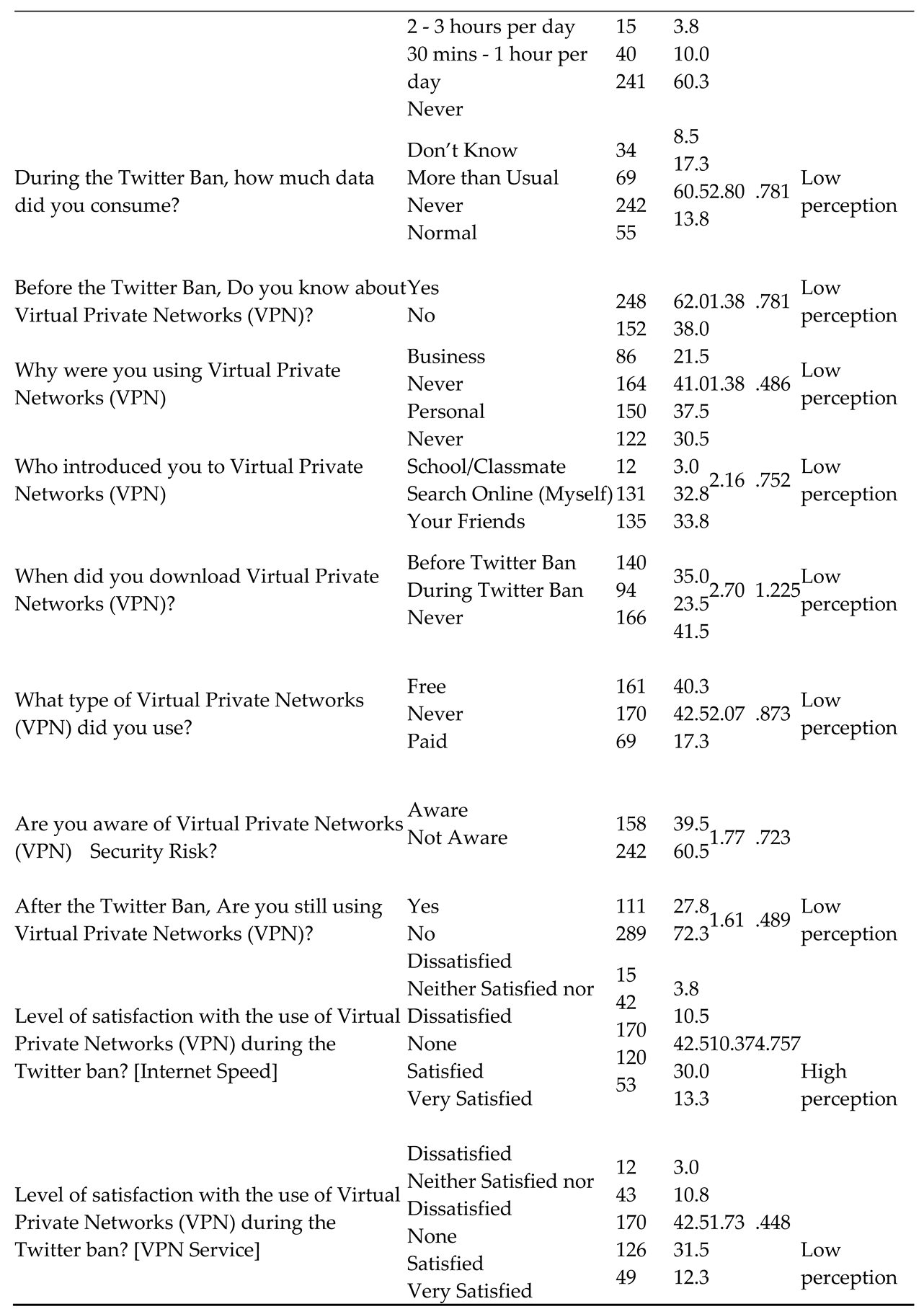

In

Table 3, The summary of the descriptive statistics is shown in

Table 3 illustrates the mean (

and standard deviation (SD) for all factors is summarized as; ‘Do you use social media’? were 1.01 and 0.086 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean; for factors ‘Do you use Twitter?’ were 1.29 and 0.454 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean; factors ‘ How long have you been using Twitter?’ were 4.21 and 1.394 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean; factors before the Twitter Ban, how often do you use Twitter? were 4.29 and 1.662 respectively showing a value higher than the weighted mean; for the factor before the Twitter Ban, how many hours per day do you spend on Twitter? were 2.95 and 1.684 respectively showing a value higher than the weighted mean. Also, factors ‘during the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?’ were 1.61 and 0.488 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. Factors ‘During the Twitter Ban, how were you able to access Twitter in Nigeria?’ were 1.39 and 0.489 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. Factors ‘During the Twitter Ban, how often did you use Twitter?’ were 4.62 and 1.381 respectively showing a value higher than the weighted mean. Moreso, factors ‘during the Twitter Ban, how many hours per day do you spend on Twitter?’ were 4.72 and 1.874 respectively showing a value higher than the weighted mean. Factors ‘During the Twitter Ban, how much data did you consume?’ were 2.80 and 0.781 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. Factors ‘before the Twitter Ban, do you know about Virtual Private Networks (VPN)?’ were 1.38 and 0.781 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. Factors ‘Why were you using Virtual Private Networks (VPN)’ were 1.38 and 0.486 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. Furthermore, factors ‘Who introduced you to Virtual Private Networks (VPN)’ were 2.16 and 0.752 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. Factor ‘When did you download Virtual Private Networks (VPN)?’ were 2.70 and 1.225 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. ‘What type of Virtual Private Network (VPN) did you use? shows X

2 and SD of 2.07 and 0.873 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. X

2 and P-value of ‘Are you aware of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) security risk?’ were 1.77 and 0.723 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. X

2 and SD of ‘After the Twitter Ban, are you still using Virtual Private Networks (VPN)?’ were 1.61 and 0.489 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean. Also, X

2 and SD of ‘level of satisfaction with the use of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) during the Twitter ban? [Internet Speed]’ were 10.37 and 4.757 respectively showing a value higher than the weighted mean. Lastly, X

2 and P-value of ‘level of satisfaction with the use of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) during the Twitter ban? [VPN Service]’ were 1.73 and 0.448 respectively showing a value lower than the weighted mean.

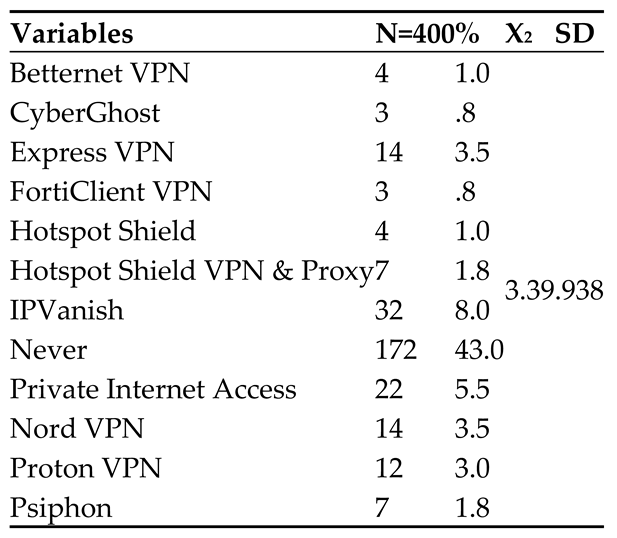

From

Table 4 below, the result showed that 10 respondents used the following VPN to download;4 respondents downloaded with Betternet VPN, 3 of the respondents used CyberGhost, 14 of the respondents used Express VPN, 3 of the respondents used FortiClient VPN, 4 of the respondents used Hotspot Shield, 7 of the respondents used Hotspot Shield VPN & Proxy, 32 of the respondents used IPVanish, 172 of the respondents used none of the brands, also, 22 of the respondents used Private Internet Access, 14 of the respondents used Nord VPN, 12 of the respondents used Proton VPN and 7 of the respondents used Psiphon.

However, from the statistics shown above, it can be deduced that most of the respondents downloaded a VPN brand called “IPVanish” to download Twitter during the Twitter ban.

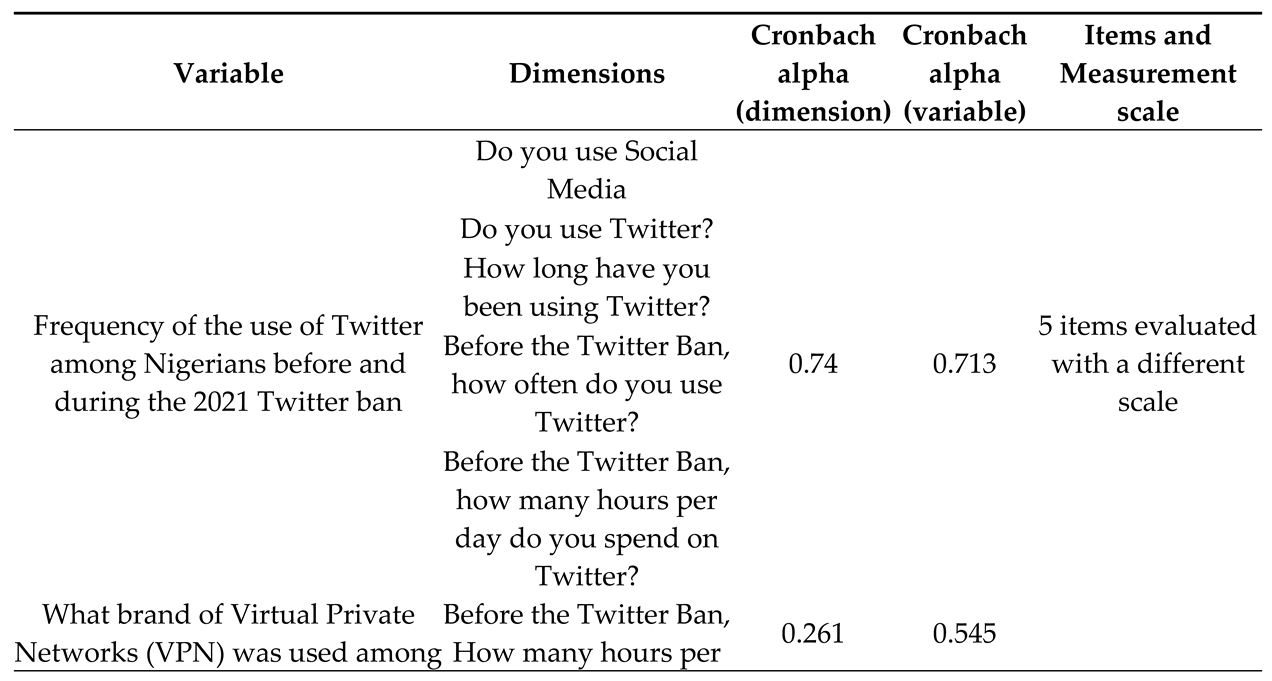

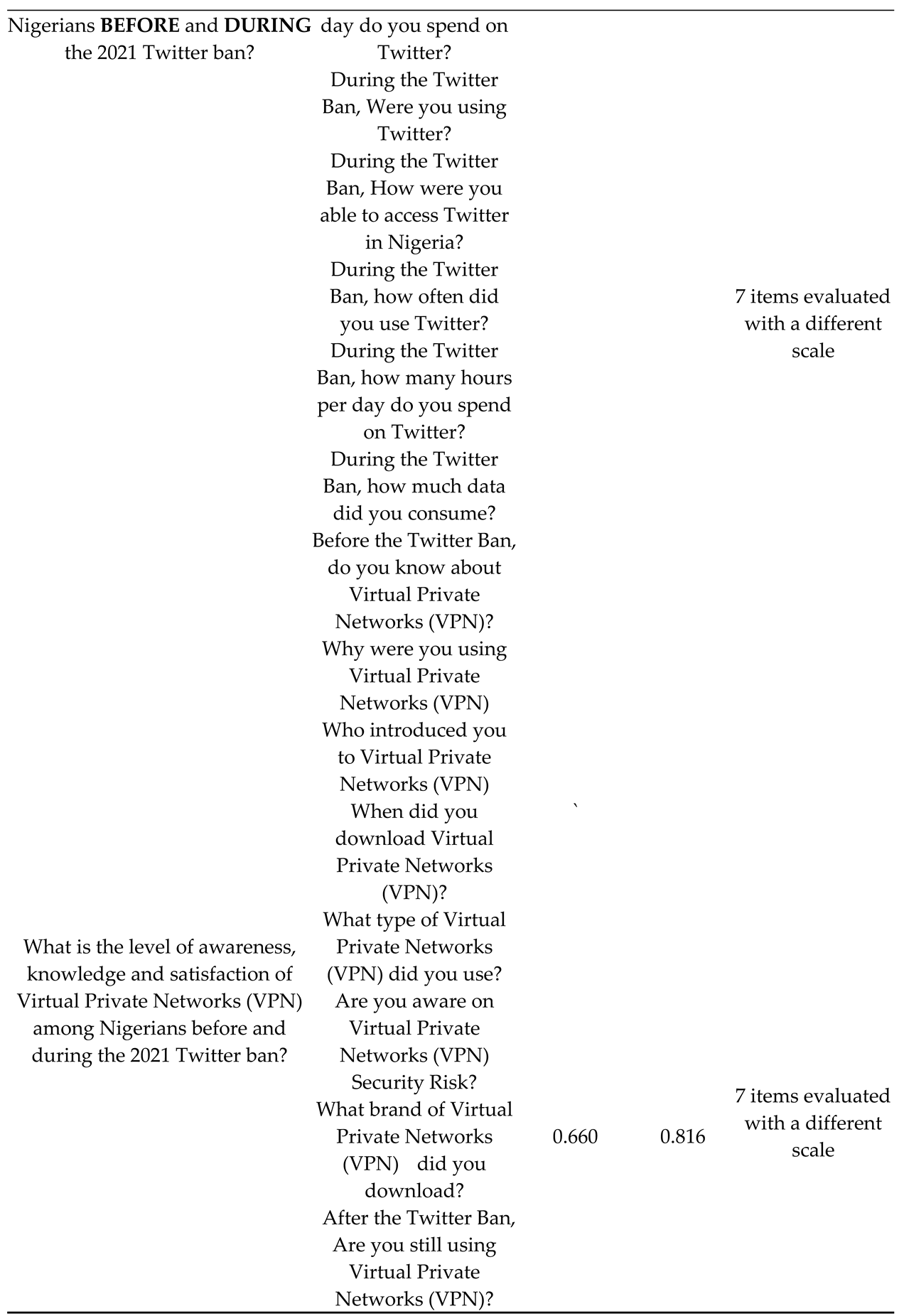

4.5. Reliability of the Instrument

Table 5 reveals that Cronbach’s coefficient alphas were computed for each dimension to determine the internal consistency reliability of the research instruments used in the study.

Table 6 shows the Cronbach’s Alpha values for the variables of the study. According to Nunnally et al, (1994), a value of 0.60 is considered the lower limit of acceptability for Cronbach’s alpha. As shown in

Table 6, all variables in this study had alpha values of 0.627 to 0.816 which were all above 0.60. This indicates a good standard of reliability that is supported by the viewpoint that the higher the degree of consistency and stability in an instrument, the higher the reliability (Moser & Kalton, 2017).

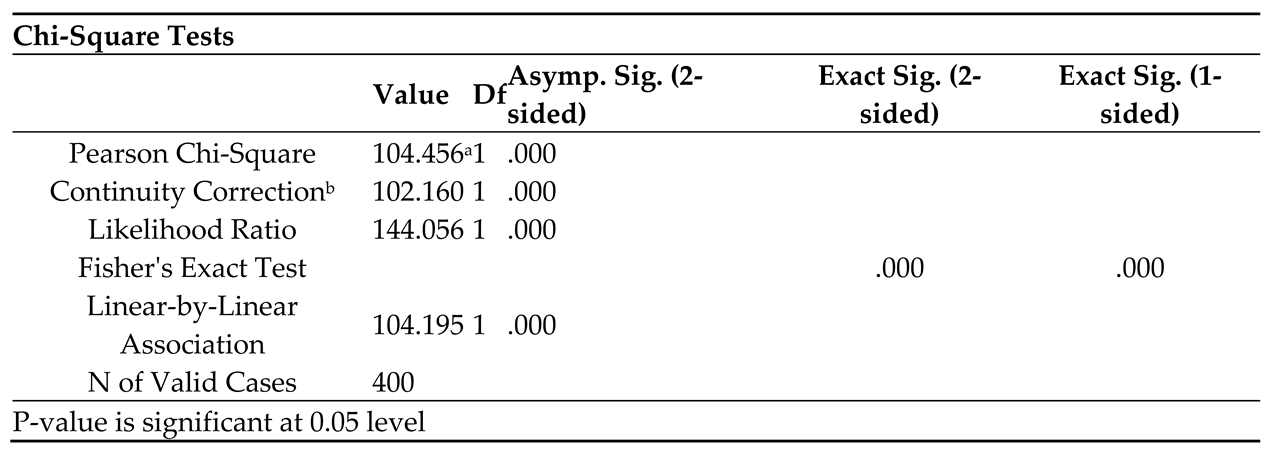

4.6. Pearson Correlation testing for a relationship between ‘Do you use Twitter?” and “During the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?”

Table 6 shows the Pearson Chi-Square test was performed to determine the relationship between

‘do you use Twitter” and “during the Twitter ban, were you using Twitter?’. However, the P-value is significant at 0.05 level; Pearson chi-square is significant with χ(1) = 104.456,

= 0.00. The result showed that the P-value (0.005) is lesser than the significant value (

) at 0.00, therefore there is a strong relationship between the two variables.

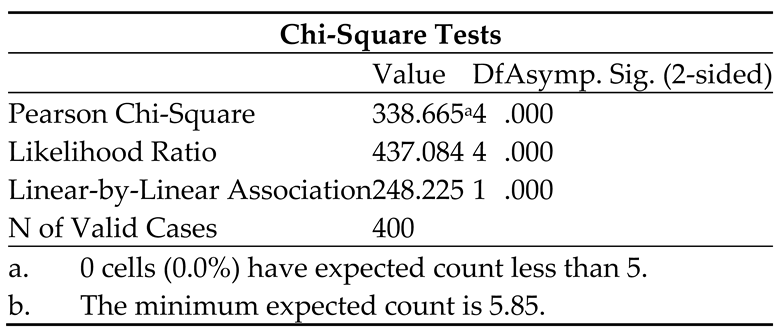

4.7. Pearson Correlation testing for the relationship ‘During the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?” and “Level of Satisfaction on Internet Speed’.

Table 7 shows the Pearson Chi-Square test was performed to determine the relationship between the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?” and “Level of Satisfaction on Internet Speed’. However, the P-value is significant at 0.05 level; Pearson chi-square is significant with χ(1) = 338.665,

= 0.00. The result showed that the P-value (0.005) is lesser than the significant value (

) at 0.00, therefore there is a strong relationship between the two variables.

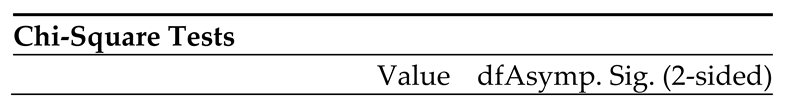

4.8. “During the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?” and “Level of Satisfaction on VPN Services)”.

Table 8 shows the Pearson Chi-Square test was performed to determine the relationship between the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?” and “Level of Satisfaction on VPN Services)”. However, the P-value is significant at 0.05 level; Pearson chi-square is significant with χ(1) = 332.178,

= 0.00. The result showed that the P-value (0.005) is lesser than the significant value (

) at 0.00, therefore there is a strong relationship between the two variables.

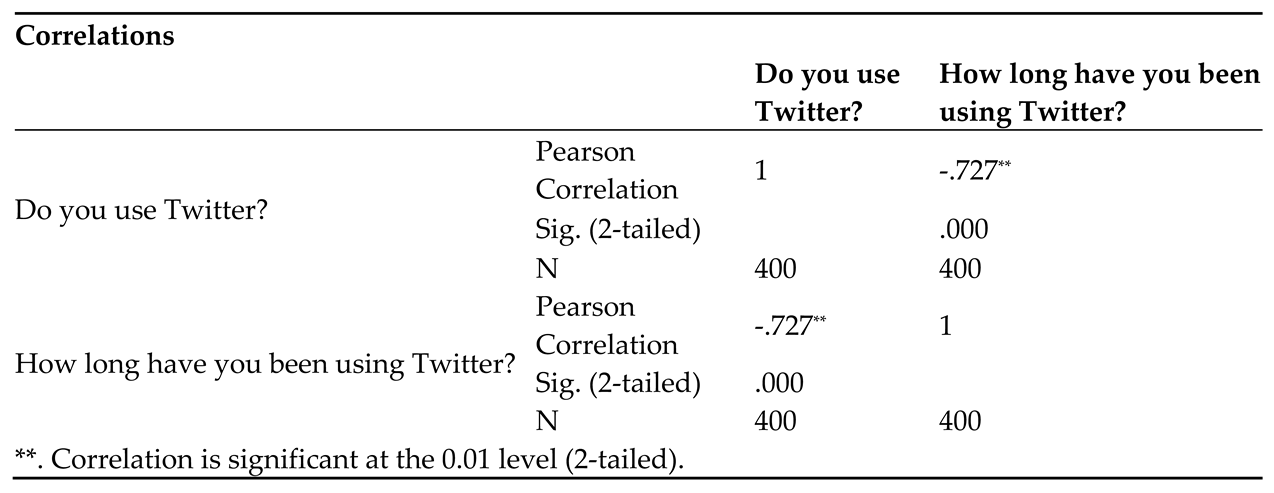

4.9. Correlation of relationship between Do you use Twitter?” and How long have you been using Twitter?

Table 9 shows the result below showed that there is a strong and statistically significant link between how often Nigerians use Twitter and how long they use it. The relationship is said to be "high" and "positive," which means that when one variable goes up, the other one likes to go up, too. The p-value is extremely low (P> 0.01), which means that the connection is very unlikely to have happened by chance. The association coefficient (r = 0.727) is close to 1, which shows that the two variables are strongly linked in a good way. The significance level is 0.000, which backs up the idea that the connection is very important. The results show that as Nigerians use Twitter more often, they tend to use it for longer periods. This study could help us figure out how people use Twitter in Nigeria and what trends there are.

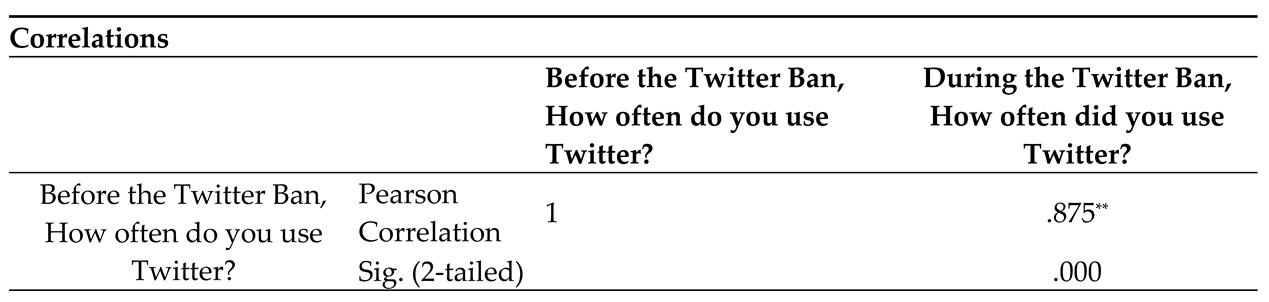

4.10. Correlation of “Before the Twitter Ban, how often do you use Twitter?” and “During the Twitter Ban, how often did you use Twitter?”

Table 10 shows an obvious and positive correlation between Twitter use before and after the ban is shown in

Table 10. The correlation is quite large and positive, suggesting that regular Twitter users have a strong tendency to keep using the service despite the restriction. Having a p-value of less than 0.001 indicates a statistically significant result. A high positive correlation is indicated by the r value of .875. The Sig value is 0.00, indicating that the association is statistically significant. In general, the statistics indicate a robust trend towards greater Twitter usage before and during the ban.

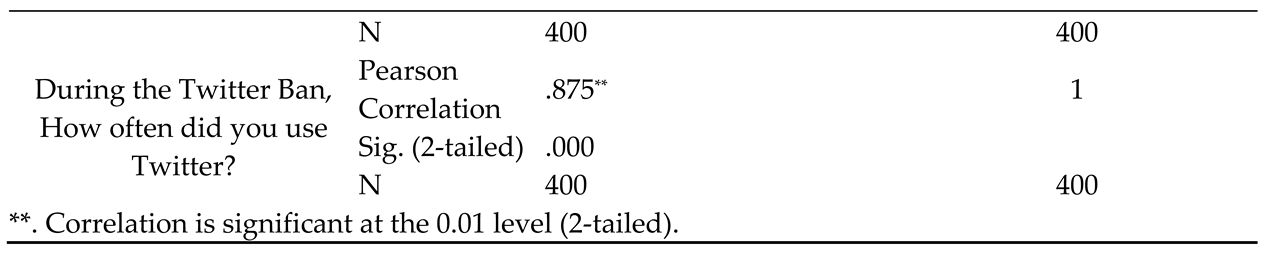

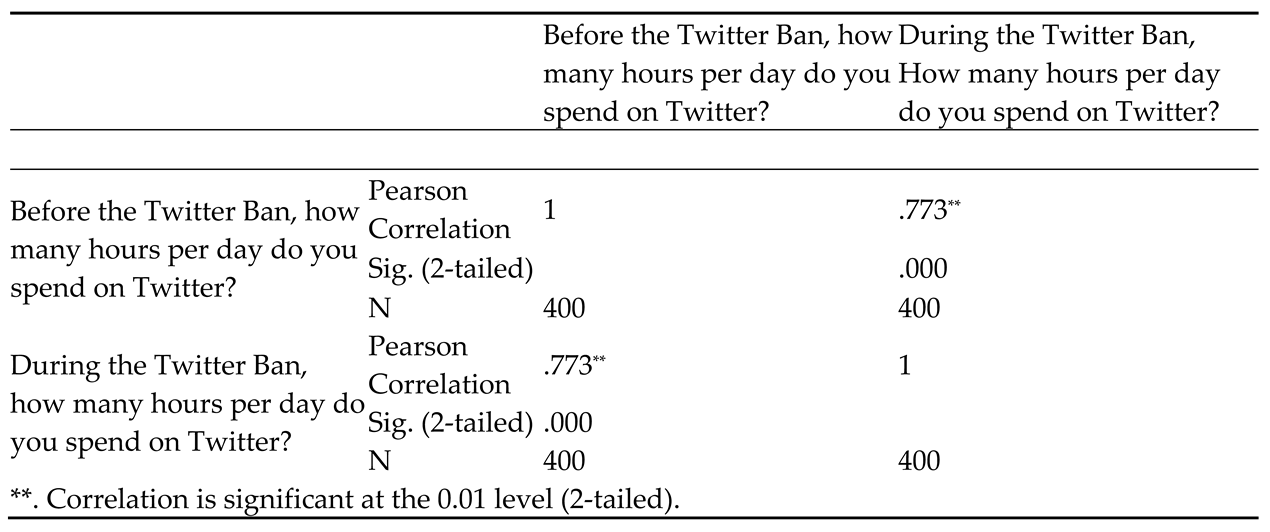

4.11. Pearson Correlation of “Before the Twitter Ban, how many hours per day do you spend” on Twitter? and “During the Twitter Ban, how many hours per day do you spend on Twitter?”

Table 11 shows a significant relationship between the time spent on Twitter before and during the Twitter Ban among Nigerian citizens. This relationship is described as "highly positive" or "strongly positive," meaning that as one variable increases, the other tends to increase. The statistical significance of this relationship is highlighted by the extremely small p-value (P < 0.001), which is considered highly significant. The correlation coefficient (r = 0.773) suggests a strong positive correlation between the two variables, meaning that as the time spent on Twitter before the ban increases, there is a corresponding increase in the time spent on Twitter during the ban among Nigerian citizens. In summary, the result suggests that on average, individuals who spent more time on Twitter before the ban tend to spend more time on Twitter during the ban.

DISCUSSIONS AND FINDINGS

The study evaluates the Impact of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) on Nigerians during the 2021 Twitter Ban. However, four objectives were designed for this study, they are; what is the frequency of the use of Twitter among Nigerians before and during the 2021 Twitter ban?; what brand of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) was used among Nigerians before and during the 2021 Twitter ban?; what is the level of awareness, knowledge and satisfaction of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) among Nigerians before and during the 2021 Twitter ban? And what is the gender and age range of social media users in Nigeria?

However, the summary of the study was highlighted according to the objectives.

Objective One: The results of this research provide insight into how frequently Nigerians used Twitter before and during the ban in 2021. Two-hundred-eighty (282) of the 400 people polled were regular Twitter users before to the ban. This percentage, which is well above the 50% threshold, implies that Twitter was the preferred channel for many responders before the ban. During the ban, however, things changed dramatically, with only 244 of the original 400 respondents saying they used Twitter. This drastic drop in Twitter usage during the ban reflects the widespread disorder in Nigeria's social media scene.

In addition,

Table 6 discusses the Pearson Correlation testing for the relationship between ‘Do you use

Twitter?” and “During the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?”, the results showed a strong significant relationship at (P-value =0.005; = 0.00). In summary, the data highlights a significant difference in Twitter usage trends during different eras. Twitter was widely used among the questioned Nigerians before the ban, but usage dropped significantly during the suspension. These results are a reflection of the ban's effect on social media usage and a testament to Twitter's continued viability as a communication tool in Nigeria's online environment.

Objective Two: The study's findings offer significant insights into the adoption of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) among Nigerian users, both before and during the implementation of the Twitter ban in 2021. In

Table 3, an analysis was conducted to investigate the methods employed by respondents to access Twitter during the ban. It is worth mentioning that a considerable proportion of respondents did not utilise Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) to access Instagram before the ban. This observation is supported by the X

2 value of 1.39 and a p-value of 0.489, which did not reach statistical significance. This finding indicates that a considerable number of participants either refrained from utilising Instagram or sought alternative means of accessing the platform that did not necessitate the use of virtual private networks (VPNs).

Moreso,

Table 4 provides insight into the particular brands of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) that were downloaded by the respondents. IPVanish was identified as the VPN of choice, as indicated by 32 respondents selecting it. The widespread use of IPVanish can be ascribed to various elements, including its renowned reputation for robust security measures, compatibility with multiple connection protocols, absence of data transfer restrictions, supply of a proxy web server, and availability of customer care around the clock. Additionally, the convenience of its interoperability with a wide range of devices and its varied pricing options, including monthly (

$11.99), annual (

$3.49), or biannual (

$2.99) plans, positions it as a favourable alternative in comparison to other brands.

In summary, the results of this study suggest that the utilisation of virtual private networks (VPNs) for accessing Instagram was not prevalent among the participants before the implementation of the Twitter prohibition. Nevertheless, IPVanish emerged as the favoured option amidst the embargo owing to its esteemed reputation for providing high-quality services and its adaptable pricing structure. These factors undoubtedly played a significant role in its appeal among Nigerian individuals who aimed to bypass the block and gain access to social media platforms such as Twitter. The provided data offers significant insights into the behaviour and preferences exhibited by Nigerian internet users during the period of the ban. This information holds potential value in comprehending the consequences of such bans on online activity and user decision-making.

Objective three: The impact of the findings on the awareness, understanding, and satisfaction levels of Nigerians regarding Virtual Private Networks (VPN) before and during the 2021 Twitter ban is significant.

The data presented in

Table 3 indicates that before the implementation of the Twitter ban, respondents displayed a limited level of familiarity with VPNs. This is supported by the result (X2 = 0.781 and P-value = 1.38). also, the result implies that, overall, Nigerians possessed a restricted understanding of virtual private networks (VPNs) before the implementation of the ban.

In contrast, after the imposition of the ban on Twitter, the analysis demonstrates an escalation in the level of familiarity with virtual private networks (VPNs), as evidenced by a distinguished increase in the Chi-square value (X2 = 2.70). However, it is important to note that the p-value (P-value = 1.225) remains statistically insignificant. This observation suggests that the implementation of the ban may have encouraged certain persons to acquire VPNs, while a significant portion of them still exhibited limited understanding, awareness, or contentment concerning their utilisation.

In summary, the findings suggest that despite the implementation of the Twitter ban, there was a notable increase in the level of awareness regarding virtual private networks (VPNs) among Nigerians. However, it is important to note that a significant portion of the population still exhibited limited awareness, knowledge, and satisfaction about VPNs, both before and during the ban. This highlights the necessity for educational initiatives and outreach programmes aimed at promoting awareness and understanding of online privacy solutions such as Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) within the Nigerian environment.

Objective Four: What is the gender and age range of social media users in Nigeria?

The findings derived from the data shown in

Table 2 offer significant insights into the distribution of social media users in Nigeria for gender and age. The data collected from the survey reveals that there is a notable discrepancy in social media usage between males and females, with 224 males and 176 females being included in the sample. Nevertheless, the statistical examination demonstrates that the observed disparity lacks statistical significance, as indicated by the outcome (X² = 1.44, p-value = 0.497). on the other hand, based on the result, it can be shown that the age group with the largest proportion of social media users corresponds to individuals between the ages of 21 and 25. The statistical significance of this age group's dominance is shown by the application mean and standard deviation (X² = 4.13, p-value = 1.105).

In summary, the results indicate that within the examined sample, the majority of social media users in Nigeria fall within the age range of 21 to 25 years. However, there is no statistically significant variance in social media usage depending on gender. These findings have the potential to shape focused marketing and outreach tactics for social media platforms in Nigeria.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study on "The Impact of Virtual Private Network (VPN) on Nigerians during the 2021 Twitter Ban" illuminates several critical facets of the intricate interplay between social media dynamics, VPN adoption, and demographic factors in Nigeria. The research delineated a significant downturn in Twitter usage during the ban, underscoring the profound influence of regulatory interventions on social media habits within the Nigerian populace. Notably, IPVanish emerged as the favoured VPN brand, a choice attributed to its robust security features and adaptable pricing options. The study's revelations also underscore a noteworthy surge in awareness regarding VPNs post-ban, emphasizing the imperative for educational initiatives geared toward enhancing understanding and promoting the adoption of online privacy solutions.

Moreover, the investigation delved into the demographic landscape of social media users in Nigeria, revealing that, while no statistically significant gender difference in social media usage was observed, the age group of 21 to 25 emerged as the predominant demographic. This insight provides valuable cues for targeted marketing and outreach strategies for social media platforms in the Nigerian context. Collectively, these findings emphasise the nuanced relationship between regulatory measures, technology adoption, and user behaviour, emphasising the need for adaptive regulatory approaches and ongoing educational campaigns to navigate the evolving landscape of online interactions in Nigeria. The study, therefore, contributes substantively to the understanding of the multifaceted impact of the 2021 Twitter ban and the broader implications for the digital landscape in Nigeria.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In light of the study's findings, several recommendations emerge to address the challenges posed by social media bans and user responses:

Firstly, it is crucial to embark on educational initiatives aimed at bolstering public awareness and comprehension of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and online privacy. Targeted campaigns can empower users with the knowledge needed to make informed decisions, thereby mitigating potential risks associated with circumventing social media bans.

Social media platforms, recognizing the unique dynamics of the 21-25 age group, should adapt their strategies accordingly. Tailoring platform features and engagement techniques to resonate with this demographic can contribute to a more inclusive and compelling online experience.

Additionally, fostering open and constructive dialogue between the government and social media users is imperative. Establishing communication channels can facilitate the resolution of concerns on both ends, potentially minimizing the likelihood of future bans and ensuring a collaborative approach to policy development.

LIMITATIONS

This study offers valuable insights into the repercussions of the 2021 Twitter ban on online communication dynamics in Nigeria. However, it is crucial to transparently address inherent limitations that may impact the interpretation and generalizability of the findings. Firstly, the sample's potential bias, mainly consisting of active social media users, particularly on Twitter, raises concerns about the representation of non-users or those on alternative platforms. Additionally, despite efforts to ensure diversity, the urban-centric nature of the sample with consistent internet access may limit broader applicability, especially in rural settings with distinct socio-economic contexts. Methodological limitations, including the potential for response bias in the online survey format and reliance on self-reported data susceptible to social desirability bias, warrant consideration. Temporal constraints focused on the ban's duration may limit capturing evolving trends, emphasizing the need for future longitudinal research. External factors, such as concurrent events, might influence participant responses, highlighting the challenge of isolating the ban's impact. Recognizing these limitations is crucial for a nuanced interpretation and lays the groundwork for future research endeavours to address and extend the insights garnered by this study. Researchers are urged to consider these constraints in the broader context of the study's objectives and implications for theory and practice.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Looking ahead, future research endeavours could delve into the enduring impacts of social media bans on online communication by employing longitudinal analyses to discern evolving user behaviours and societal dynamics. Cross-cultural comparative studies are warranted to unravel the contextual nuances in the effects of bans, considering diverse cultural landscapes and governmental policies. Qualitative explorations through interviews or focus groups could unveil the intricate emotional and psychological dimensions of users' experiences during and post-ban periods. In the realm of VPN usage, a nuanced investigation into the motivations behind user choices, a comparative analysis of VPN brands, and an examination of government responses to VPN adoption can enrich our understanding. Furthermore, evaluating the effectiveness of educational initiatives aimed at enhancing awareness of online privacy solutions is crucial. Global comparative studies across countries facing similar censorship challenges can provide a broader perspective. These avenues of research promise to advance scholarly discourse and deepen comprehension of the intricate interplay between regulatory interventions, technology adoption, and user behaviour in the digital age.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research (Self-funding).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the research presented in this article.

References

- Gaikar, V. (2014). What is VPN and why do I need it? Tricks Machine. Retrieved February 23, 2022, from https://www.tricksmachine.com/2013/05/what-is-vpn.html.

- Njoku, L.; Olumide, S.; Daka, T.; Ugoeze, N. O.; Abuh, A.; Nzor, E.; and Osibe, O. (2021, June 3). Fireworks, Anger Trail Buhari’s ‘Shock Threat’ to Secessionist. The Guardian, 37 (15498), pp. 1-2.

- Eze, M.; Taiwo, J.; Obi, O. O. and Nweje, C. (2021, June 3). FG Fumes as Twitter Pulls Down Buhari’s Civil War Tweet. Daily Sun, 17 (4723), P.6.

- Okonofua, D. O. (2021). Twitter ban in Nigeria: A metaphor for impediment on uses and gratification theory. International Journal of Social Sciences, 4(1), 198-206. https://doi.org/10.31295/ijss.v4n1.1665.

- Akresh, R., Bhalotra, S., Leone, M., & Osili, U. O. (2012). War and stature: Growing up during the Nigerian civil war. American Economic Review, 102(3), 273-77. [CrossRef]

- Jindal, S., Tyagi, A. K., & Sharma, K. (2020). Twitter user’s Behavior and Events Affecting Their Mood. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 9(3), 3222–3226. [CrossRef]

- Boateng, R., & Amankwaa, A. (2016). The impact of social media on student academic life in higher education. Global Journal of Human-Social Science, 16(4), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Oden, C. (2021). The effect of twitter ban on the economy of Nigeria. Pista Technologies. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.projecttopics.org/the-effect-of-twitter-ban-on-the-economy-of-nigeria.html.

- Al-Rahmi, W., & Othman, M. (2013). The impact of social media use on academic performance among university students: A pilot study. Journal of information systems research and innovation, 4(12), 1-10.

- Mosleh, M., Pennycook, G., Arechar, A. A., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Cognitive reflection correlates with behavior on Twitter. Nature Communications, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Dewing, M. (2010). Social media: An introduction (Vol. 1). Ottawa: Library of Parliament.

- Abdulrauf-Salau, A. (2013). Twitter as News Source to Select Audiences in Ilorin, Nigeria. African Council for Communication Education (ACCE).

- Ekoh, P. C., & George, E. O. (2021). The role of digital technology in the EndSars protest in Nigeria during Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of human rights and social work, 6(2), 161-162. [CrossRef]

- Eligon, J. (2020). Black Lives Matter grows as movement while facing new challenges. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/28/us/black-lives-matter-protest.html.

- Coyle, J. (2009). Is twitter the news outlet for the 21st century? ABC News. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://abcnews.go.com/Technology/story?id=7979891&page=1.

- Li, X., Lee, F. L., & Li, Y. (2016). The dual impact of social media under networked authoritarianism: Social media use, civic attitudes, and system support in China. International Journal of Communication, 10, 21.

- Amarasingam, A., & Rizwie, R. (2020). Turning the Tap Off: The Impacts of Social Media Shutdown After Sri Lanka's Easter Attacks. International Centre for Counter-Terrorism.

- Amarasingham, A. (2019). Terrorism on the teardrop island: Understanding the Easter 2019 attacks in Sri Lanka. CTC Sentinel, 12(5), 1-10. https://ctc.usma.edu/terrorism-teardrop-island-understanding-easter-2019-attacks-sri-lanka/.

- Al Jazeera. (2019, May 2). Sri Lanka bombings: All the latest updates. Sri Lanka Bombing News | Al Jazeera. Retrieved March 2022, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/5/2/sri-lanka-bombings-all-the-latest-updates.

- Network P. (2019). Tunnel up / tunnel down: What is a VPN. Internet Archive. Retrieved March 2022, from https://archive.org/details/vpn-zines/zine-VPN-screen/.

- Nyekwere, E. O., Okoro, N., & Azubuike, C. (2014). An assessment of the use of social media as advertising vehicles in Nigeria: A study of Facebook and Twitter. New Media and Mass Communication, 21(1), 1-8.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The Assessment of Reliability. Psychometric Theory, 3, 248-292. Nyhan, RC, and HA Marlowe.(1997). Development And Psychometric Properties Of The Organizational Trust Inventory. Evaluation Review, 21(5), 614-635. [CrossRef]

- Moser, C. A., & Kalton, G. (2017). Survey methods in social investigation. Routledge.

Table 1.

Which Social Media Platform do you use?

Table 1.

Which Social Media Platform do you use?

Table 2.

Table showing responses on Social Demographic of the respondents.

Table 2.

Table showing responses on Social Demographic of the respondents.

Table 3.

Table showing responses on the Impact of Virtual Private Network (VPN) On Nigerians During The 2021 Twitter Ban.

Table 3.

Table showing responses on the Impact of Virtual Private Network (VPN) On Nigerians During The 2021 Twitter Ban.

Table 4.

What brand of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) did you download?

Table 4.

What brand of Virtual Private Networks (VPN) did you download?

Table 5.

Summary of Reliability Analysis.

Table 5.

Summary of Reliability Analysis.

Table 6.

Pearson Correlation testing for a relationship between ‘Do you use Twitter?” and “During the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?”.

Table 6.

Pearson Correlation testing for a relationship between ‘Do you use Twitter?” and “During the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?”.

Table 7.

Pearson Correlation testing for relationship ‘during the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?” and “Level of Satisfaction on Internet Speed’.

Table 7.

Pearson Correlation testing for relationship ‘during the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?” and “Level of Satisfaction on Internet Speed’.

Table 8.

During the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?” and “Level of Satisfaction on VPN Services).

Table 8.

During the Twitter Ban, were you using Twitter?” and “Level of Satisfaction on VPN Services).

Table 9.

Correlation of relationship between do you use Twitter?” and how long have you been using Twitter.

Table 9.

Correlation of relationship between do you use Twitter?” and how long have you been using Twitter.

Table 10.

Correlation of “Before the Twitter Ban, how often do you use Twitter?” and “During the Twitter Ban, how often did you use Twitter?”.

Table 10.

Correlation of “Before the Twitter Ban, how often do you use Twitter?” and “During the Twitter Ban, how often did you use Twitter?”.

Table 11.

Pearson Correlations table of “before the Twitter ban, how many hours per day do you spend” on Twitter? and “during the Twitter Ban, how many hours per day do you spend on Twitter?”.

Table 11.

Pearson Correlations table of “before the Twitter ban, how many hours per day do you spend” on Twitter? and “during the Twitter Ban, how many hours per day do you spend on Twitter?”.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).