Submitted:

19 December 2023

Posted:

20 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

PERSPECTIVES OF AT-RISK INDIVIDUALS

Preventing Parkinson’s is an Important Objective

Meaningful Input from At-Risk Individuals is Beneficial to Research

Psychology of Risk Disclosure

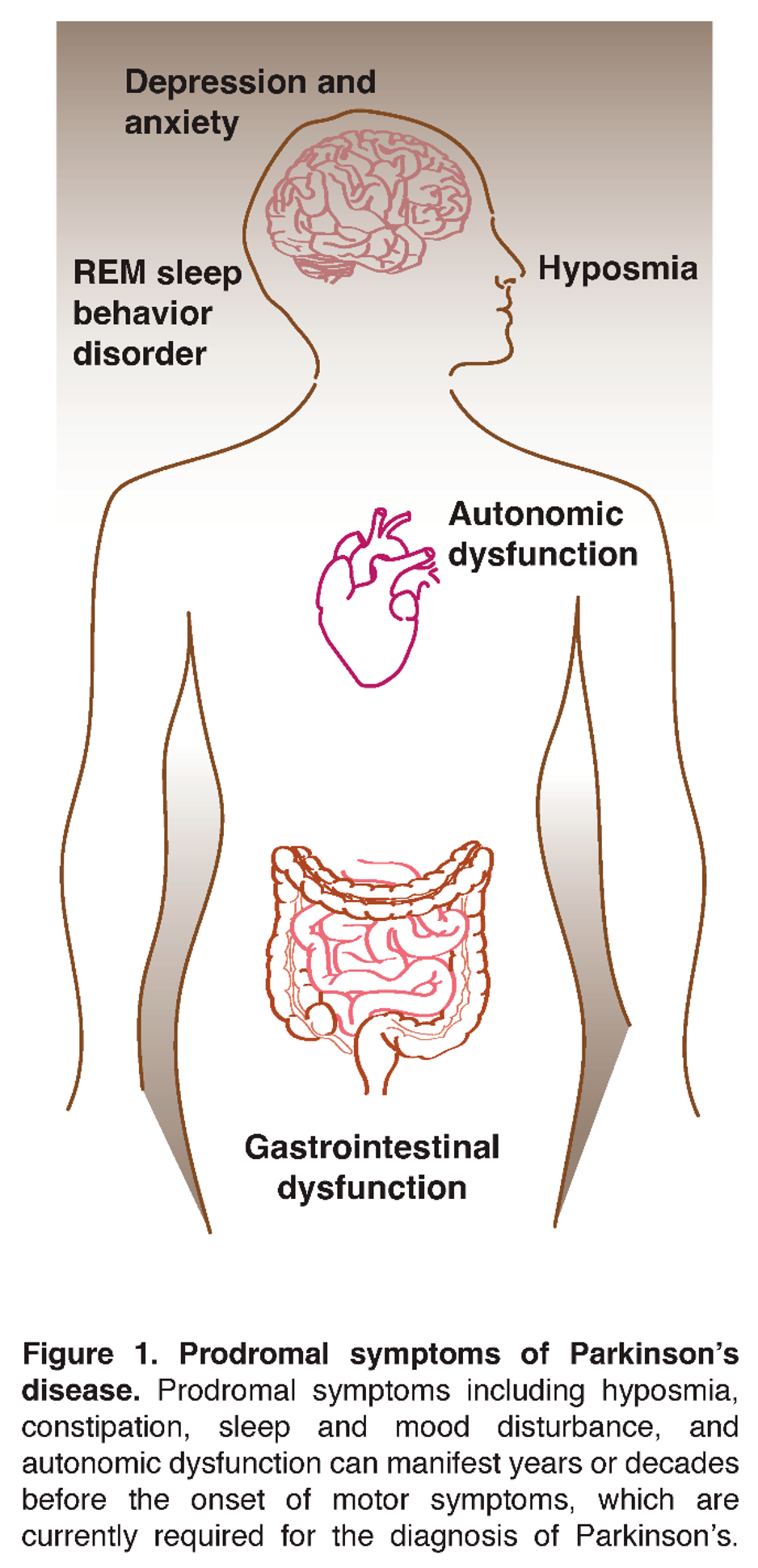

Early Symptoms

How Do At-Risk Individuals Fit into the Broader Parkinson’s Community?

Return of Individual Information

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CURRENT ENVIRONMENT

Lack of Awareness Among Primary Care Physicians & General Neurologists

Legal Implications

Identification, Training, and Engagement of At-Risk Advocates

CONCLUSION

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Reference SNP (rs) Report rs34637584 LRRK2 [Internet],National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information, Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs34637584, September 21, 2022,Accessed September 27, 2023.

- Reference SNP (rs) Report rs76763715 (GBA) [Internet],National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information, Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs76763715, September 21, 2022,Accessed September 27, 2023.

- Cicero, C.E.; Giuliano, L.; Luna, J.; Zappia, M.; Preux, P.M.; Nicoletti, A. Prevalence of idiopathic REM behavior disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep 2021, 44, zsaa294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haba-Rubio, J.; Frauscher, B.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Toriel, J.; Tobback, N.; Andries, D.; Preisig, M.; Vollenweider, P.; Postuma, R.; Heinzer, R. Prevalence and determinants of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in the general population. Sleep 2018, 41, zsx197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiato, V.M.; Levy, D.A.; Byun, Y.J.; Nguyen, S.A.; Soler, Z.M.; Schlosser, R.J. The Prevalence of Olfactory Dysfunction in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2021, 35, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.J.; Wang, Y.; Alcalay, R.N.; Mejia-Santana, H.; Saunders-Pullman, R.; Bressman, S.; Corvol, J.C.; Brice, A.; Lesage, S.; Mangone, G.; Tolosa, E.; Pont-Sunyer, C.; Vilas, D.; Schule, B.; Kausar, F.; Foroud, T.; Berg, D.; Brockmann, K.; Goldwurm, S.; Siri, C.; Asselta, R.; Ruiz-Martinez, J.; Mondragon, E.; Marras, C.; Ghate, T.; Giladi, N.; Mirelman, A.; Marder, K.; Michael, J.F.L.C.C. Penetrance estimate of LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation in individuals of non-Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Mov Disord 2017, 32, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcalay, R.N.; Dinur, T.; Quinn, T.; Sakanaka, K.; Levy, O.; Waters, C.; Fahn, S.; Dorovski, T.; Chung, W.K.; Pauciulo, M.; Nichols, W.; Rana, H.Q.; Balwani, M.; Bier, L.; Elstein, D.; Zimran, A. Comparison of Parkinson risk in Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Gaucher disease and GBA heterozygotes. JAMA Neurol 2014, 71, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Schenck, C.H.; Postuma, R.B.; Iranzo, A.; Luppi, P.H.; Plazzi, G.; Montplaisir, J.; Boeve, B. REM sleep behaviour disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X.; Zhou, C.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Li, F. Hyposmia as a Predictive Marker of Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2019, 2019, 3753786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Yan, X.; Lv, H.; Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Luo, X. Gender differences in prevalence of LRRK2-associated Parkinson disease: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Neurosci Lett 2020, 715, 134609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Jing, Y.; Lun, P.; Liu, X.; Sun, P. Association of gender and age at onset with glucocerebrosidase associated Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 2261–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, S.; Mus, L.; Blandini, F. Parkinson's Disease in Women and Men: What's the Difference? J Parkinsons Dis 2019, 9, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestenbaum M, Alcalay RN (2017) Clinical Features of LRRK2 Carriers with Parkinson’s Disease In Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 (LRRK2), Rideout HJ, ed. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 31-48.

- Ren, J.; Zhan, X.; Zhou, H.; Guo, Z.; Xing, Y.; Yin, H.; Xue, C.; Wu, J.; Liu, W. Comparing the effects of GBA variants and onset age on clinical features and progression in Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e14387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Louis, E.K.; Boeve, B.F. REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: Diagnosis, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions. Mayo Clin Proc 2017, 92, 1723–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Zhao, Y.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Q.; Tan, J.; Yan, X.; Tang, B.; Guo, J. Olfactory Dysfunction Predicts Disease Progression in Parkinson's Disease: A Longitudinal Study. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 569777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siderowf, A.; Concha-Marambio, L.; Lafontant, D.E.; Farris, C.M.; Ma, Y.; Urenia, P.A.; Nguyen, H.; Alcalay, R.N.; Chahine, L.M.; Foroud, T.; Galasko, D.; Kieburtz, K.; Merchant, K.; Mollenhauer, B.; Poston, K.L.; Seibyl, J.; Simuni, T.; Tanner, C.M.; Weintraub, D.; Videnovic, A.; Choi, S.H.; Kurth, R.; Caspell-Garcia, C.; Coffey, C.S.; Frasier, M.; Oliveira, L.M.A.; Hutten, S.J.; Sherer, T.; Marek, K.; Soto, C.; Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative. Assessment of heterogeneity among participants in the Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative cohort using alpha-synuclein seed amplification: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paisan-Ruiz, C.; Lewis, P.A.; Singleton, A.B. LRRK2: cause, risk, and mechanism. J Parkinsons Dis 2013, 3, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan-Or, Z.; Liong, C.; Alcalay, R.N. GBA-Associated Parkinson's Disease and Other Synucleinopathies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2018, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. Review: Sporadic Parkinson's disease: development and distribution of alpha-synuclein pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2016, 42, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schootemeijer, S.; van der Kolk, N.M.; Bloem, B.R.; de Vries, N.M. Current Perspectives on Aerobic Exercise in People with Parkinson's Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 1418–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Luciano, M.; Tanner, C.M.; Meng, C.; Marras, C.; Goldman, S.M.; Lang, A.E.; Tolosa, E.; Schule, B.; Langston, J.W.; Brice, A.; Corvol, J.C.; Goldwurm, S.; Klein, C.; Brockman, S.; Berg, D.; Brockmann, K.; Ferreira, J.J.; Tazir, M.; Mellick, G.D.; Sue, C.M.; Hasegawa, K.; Tan, E.K.; Bressman, S.; Saunders-Pullman, R.; Michael, J.F.F.L.C.C. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Use and LRRK2 Parkinson's Disease Penetrance. Mov Disord 2020, 35, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, G.F.; Maciuca, R.; Macklin, E.A.; Wang, J.; Montalban, M.; Davis, S.S.; Alkabsh, J.I.; Bakshi, R.; Chen, X.; Ascherio, A.; Astarita, G.; Huntwork-Rodriguez, S.; Schwarzschild, M.A. Association of caffeine and related analytes with resistance to Parkinson disease among LRRK2 mutation carriers: A metabolomic study. Neurology 2020, 95, e3428–e3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, A.; Li, X.; Gomez-Llorente, Y.; Leandrou, E.; Memou, A.; Clemente, N.; Yao, C.; Afsari, F.; Zhi, L.; Pan, N.; Morohashi, K.; Hua, X.; Zhou, M.M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.G.; Elliott, C.J.; Rideout, H.; Ubarretxena-Belandia, I.; Yue, Z. Vitamin B(12) modulates Parkinson's disease LRRK2 kinase activity through allosteric regulation and confers neuroprotection. Cell Res 2019, 29, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, G.F.; Schwarzschild, M.A. What to Test in Parkinson Disease Prevention Trials? Repurposed, Low-Risk, and Gene-Targeted Drugs. Neurology 2022, 99, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohn, L.; Ruskey, J.A.; Rudakou, U.; Leveille, E.; Asayesh, F.; Hu, M.T.M.; Arnulf, I.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Hogl, B.; Stefani, A.; Monaca, C.C.; Abril, B.; Plazzi, G.; Antelmi, E.; Ferini-Strambi, L.; Heidbreder, A.; Boeve, B.F.; Espay, A.J.; De Cock, V.C.; Mollenhauer, B.; Sixel-Doring, F.; Trenkwalder, C.; Sonka, K.; Kemlink, D.; Figorilli, M.; Puligheddu, M.; Dijkstra, F.; Viaene, M.; Oertel, W.; Toffoli, M.; Gigli, G.L.; Valente, M.; Gagnon, J.F.; Desautels, A.; Montplaisir, J.Y.; Postuma, R.B.; Rouleau, G.A.; Gan-Or, Z. GBA variants in REM sleep behavior disorder: A multicenter study. Neurology 2020, 95, e1008–e1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullin, S.; Smith, L.; Lee, K.; D'Souza, G.; Woodgate, P.; Elflein, J.; Hallqvist, J.; Toffoli, M.; Streeter, A.; Hosking, J.; Heywood, W.E.; Khengar, R.; Campbell, P.; Hehir, J.; Cable, S.; Mills, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Limousin, P.; Libri, V.; Foltynie, T.; Schapira, A.H.V. Ambroxol for the Treatment of Patients With Parkinson Disease With and Without Glucocerebrosidase Gene Mutations: A Nonrandomized, Noncontrolled Trial. JAMA Neurol 2020, 77, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, S.; Weinreb, O.; Amit, T.; Youdim, M.B. Mechanism of neuroprotective action of the anti-Parkinson drug rasagiline and its derivatives. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2005, 48, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Luo, N.; Chen, F.; Zhou, L.; Niu, M.; Kang, W.; Liu, J. Efficacy of idebenone in the Treatment of iRBD into Synucleinopathies (EITRS): rationale, design, and methodology of a randomized, double-blind, multi-center clinical study. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 981249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmering, J.E.; Welsh, M.J.; Schultz, J.; Narayanan, N.S. Use of Glycolysis-Enhancing Drugs and Risk of Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord 2022, 37, 2210–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Choi, H.I.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Hoffer, B.J.; Greig, N.H. A New Treatment Strategy for Parkinson's Disease through the Gut-Brain Axis: The Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Pathway. Cell Transplant 2017, 26, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeliovich, A.; Hefti, F.; Sevigny, J. Gene Therapy for Parkinson's Disease Associated with GBA1 Mutations. J Parkinsons Dis 2021, 11, S183–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilter, H.C.; Collison, A.; Russo, R.C.; Foot, J.S.; Yow, T.T.; Vieira, A.T.; Tavares, L.D.; Mattes, J.; Teixeira, M.M.; Jarolimek, W. Effects of an anti-inflammatory VAP-1/SSAO inhibitor, PXS-4728A, on pulmonary neutrophil migration. Respir Res 2015, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, L.M.; Merchant, K.; Siderowf, A.; Sherer, T.; Tanner, C.; Marek, K.; Simuni, T. Proposal for a Biologic Staging System of Parkinson's Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2023, 13, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höglinger GU, Adler CH, Berg D, Klein C, Outeiro TF, Poewe W, Postuma R, Stoessl J, Lang AE (2023) in Preprints Preprints.

- Cardoso, F.; Goetz, C.G.; Mestre, T.A.; Sampaio, C.; Adler, C.H.; Berg, D.; Bloem, B.R.; Burn, D.J.; Fitts, M.S.; Gasser, T.; Klein, C.; de Tijssen, M.A.J.; Lang, A.E.; Lim, S.Y.; Litvan, I.; Meissner, W.G.; Mollenhauer, B.; Okubadejo, N.; Okun, M.S.; Postuma, R.B.; Svenningsson, P.; Tan, L.C.S.; Tsunemi, T.; Wahlstrom-Helgren, S.; Gershanik, O.S.; Fung, V.S.C.; Trenkwalder, C. A Statement of the MDS on Biological Definition, Staging, and Classification of Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord. 2024, 39, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, H. A new biological classification for Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2023, 19, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Hamilton, J.L.; Kopil, C.; Beck, J.C.; Tanner, C.M.; Albin, R.L.; Ray Dorsey, E.; Dahodwala, N.; Cintina, I.; Hogan, P.; Thompson, T. Current and projected future economic burden of Parkinson's disease in the U.S. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2020, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. J Parkinsons Dis 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2016 Parkinson's Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson's disease, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marras, C.; Beck, J.C.; Bower, J.H.; Roberts, E.; Ritz, B.; Ross, G.W.; Abbott, R.D.; Savica, R.; Van Den Eeden, S.K.; Willis, A.W.; Tanner, C.M.; Parkinson's Foundation, P.G. Prevalence of Parkinson's disease across North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, A.W.; Roberts, E.; Beck, J.C.; Fiske, B.; Ross, W.; Savica, R.; Van Den Eeden, S.K.; Tanner, C.M.; Marras, C.; Parkinson's Foundation, P.G. Incidence of Parkinson disease in North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2022, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanowicz, N.; Jones, S.A.; Hauser, R.A. Impact of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease: a PMDAlliance survey. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019, 15, 2205–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lageman, S.K.; Cash, T.V.; Mickens, M.N. Patient-reported Needs, Non-motor Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Essential Tremor and Parkinson's Disease. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2014, 4, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D. Advances in markers of prodromal Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2016, 12, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.; Fereshtehnejad, S.M.; Dawson, B.K.; Pelletier, A.; Gan-Or, Z.; Gagnon, J.F.; Montplaisir, J.Y.; Postuma, R.B. Longstanding disease-free survival in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: Is neurodegeneration inevitable? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018, 54, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, D.; Klein, C. alpha-synuclein seed amplification and its uses in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niotis, K.; West, A.B.; Saunders-Pullman, R. Who to Enroll in Parkinson Disease Prevention Trials? The Case for Genetically At-Risk Cohorts. Neurology 2022, 99, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, R.B.; Myers, T.L.; Rowbotham, H.M.; Luff, M.K.; Amodeo, K.; Sharma, S.; Wilson, R.; Jensen-Roberts, S.; Auinger, P.; McDermott, M.P.; Alcalay, R.N.; Biglan, K.; Kinel, D.; Tanner, C.; Winter-Evans, R.; Augustine, E.F.; Cannon, P.; Me Research, T.; Holloway, R.G.; Dorsey, E.R. A Virtual Cohort Study of Individuals at Genetic Risk for Parkinson's Disease: Study Protocol and Design. J Parkinsons Dis 2020, 10, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, C.G.; Davis, M.A.; Grill, J.D.; Roberts, J.S. US Adults' Likelihood to Participate in Dementia Prevention Drug Trials: Results from the National Poll on Healthy Aging. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2023, 10, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sertkaya A, AnnaBerlind, Ayesha Eyraud, John (2014) ASPE Reports, Washington, DC, p. 92.

- (2020).

- (2021), Bethesda, MD.

- TransCelerate Biopharma Toolkits Core Team; Elmer, M.; Florek, C.; Gabryelski, L.; Greene, A.; Inglis, A.M.; Johnson, K.L.; Keiper, T.; Ludlam, S.; Sharpe, T.J.; Shay, K.; Somers, F.; Sutherland, C.; Teufel, M.; Yates, S. Amplifying the Voice of the Patient in Clinical Research: Development of Toolkits for Use in Designing and Conducting Patient-Centered Clinical Studies. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2020, 54, 1489–1500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harrington, R.L.; Hanna, M.L.; Oehrlein, E.M.; Camp, R.; Wheeler, R.; Cooblall, C.; Tesoro, T.; Scott, A.M.; von Gizycki, R.; Nguyen, F.; Hareendran, A.; Patrick, D.L.; Perfetto, E.M. Defining Patient Engagement in Research: Results of a Systematic Review and Analysis: Report of the ISPOR Patient-Centered Special Interest Group. Value Health 2020, 23, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.M.; Blaser, D.A.; Cone, L.; Arcona, S.; Ko, J.; Sasane, R.; Wicks, P. Increasing Patient Involvement in Drug Development. Value Health 2016, 19, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacristan, J.A.; Aguaron, A.; Avendano-Sola, C.; Garrido, P.; Carrion, J.; Gutierrez, A.; Kroes, R.; Flores, A. Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016, 10, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, K.; White, J. Democratizing clinical research. Nature 2011, 474, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury K, Christopher S, Foley J, Grossman C, Haas KL, Hemphill R, Massoud A, McCarty M, Nguyen M, Otlewski M, Rhim C, Saha A, Selig W, Tarver M, Rincon-Gonzalez L, Steele D (2021) Maximizing Patient Input in the Design and Development of Medical Device Clinical Trials. A Report of the Science of Patient Input Program of the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC). Arlington, VA.

- Johns H, Chowdhury S, Simon G, Corrigan P (2014) Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, Transcript, Meeting 17, Session 4. Atlanta, GA.

- Hewlett, S.; Wit, M.; Richards, P.; Quest, E.; Hughes, R.; Heiberg, T.; Kirwan, J. Patients and professionals as research partners: challenges, practicalities, and benefits. Arthritis Rheum 2006, 55, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, T.; Cleanthous, S.; Andrejack, J.; Barker, R.A.; Blavat, G.; Brooks, W.; Burns, P.; Cano, S.; Gallagher, C.; Gosden, L.; Siu, C.; Slagle, A.F.; Trenam, K.; Boroojerdi, B.; Ratcliffe, N.; Schroeder, K. Patient Experience in Early-Stage Parkinson's Disease: Using a Mixed Methods Analysis to Identify Which Concepts Are Cardinal for Clinical Trial Outcome Assessment. Neurol Ther 2022, 11, 1319–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, I.; Glasziou, P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Obstet Gynecol 2009, 114, 1341–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiopoulos, S.; Michaels, D.L.; Kunz, B.L.; Getz, K.A. Measuring the Impact of Patient Engagement and Patient Centricity in Clinical Research and Development. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2020, 54, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, J.C.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Parker, A.; Hirst, J.A.; Chant, A.; Petit-Zeman, S.; Evans, D.; Rees, S. Impact of patient and public involvement on enrolment and retention in clinical trials: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018, 363, k4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domecq, J.P.; Prutsky, G.; Elraiyah, T.; Wang, Z.; Nabhan, M.; Shippee, N.; Brito, J.P.; Boehmer, K.; Hasan, R.; Firwana, B.; Erwin, P.; Eton, D.; Sloan, J.; Montori, V.; Asi, N.; Dabrh, A.M.; Murad, M.H. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkani, R.G.; Wenger, N.S. REM Sleep Behavior Disorder as a Pathway to Dementia: If, When, How, What, and Why Should Physicians Disclose the Diagnosis and Risk for Dementia. Curr Sleep Med Rep 2021, 7, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Karlawish, J.; Berkman, B.E. Ethics of genetic and biomarker test disclosures in neurodegenerative disease prevention trials. Neurology 2015, 84, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, E.; Rogge, A.; Nieding, K.; Helmker, V.; Letsch, C.; Hauptmann, B.; Berg, D. Patients' views on the ethical challenges of early Parkinson disease detection. Neurology 2020, 94, e2037–e2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deslippe, A.L.; Soanes, A.; Bouchaud, C.C.; Beckenstein, H.; Slim, M.; Plourde, H.; Cohen, T.R. Barriers and facilitators to diet, physical activity and lifestyle behavior intervention adherence: a qualitative systematic review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2023, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gossard, T.R.; Teigen, L.N.; Yoo, S.; Timm, P.C.; Jagielski, J.; Bibi, N.; Feemster, J.C.; Steele, T.; Carvalho, D.Z.; Junna, M.R.; Lipford, M.C.; Tippmann Peikert, M.; LeClair-Visonneau, L.; McCarter, S.J.; Boeve, B.F.; Silber, M.H.; Hirsch, J.; Sharp, R.R.; St Louis, E.K. Patient values and preferences regarding prognostic counseling in isolated REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 2023, 46, zsac244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Carbonell, L.; Simonet, C.; Chohan, H.; Gill, A.; Leschziner, G.; Schrag, A.; Noyce, A.J. The Views of Patients with Isolated Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder on Risk Disclosure. Mov Disord 2023, 38, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, M.; Avidan, A.Y.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N.; Malkani, R.G.; During, E.H.; Roland, J.P.; McCarter, S.J.; Zak, R.S.; Carandang, G.; Kazmi, U.; Ramar, K. Management of REM sleep behavior disorder: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2023, 19, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmi, L.; Blease, C.; Hagglund, M.; Walker, J.; DesRoches, C.M. US policy requires immediate release of records to patients. BMJ 2021, 372, n426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeve, B.F. REM sleep behavior disorder: Updated review of the core features, the REM sleep behavior disorder-neurodegenerative disease association, evolving concepts, controversies, and future directions. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010, 1184, 15–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fereshtehnejad, S.M.; Yao, C.; Pelletier, A.; Montplaisir, J.Y.; Gagnon, J.F.; Postuma, R.B. Evolution of prodromal Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: a prospective study. Brain 2019, 142, 2051–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Patterson, C.; Hsu, J.Y.; Willis, A.W.; Hamedani, A.G. Functional Impairment in Individuals With Prodromal or Unrecognized Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurol 2023, 80, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, L.K.; Alschuler, D.M.; Wall, M.; Luttmann-Gibson, H.; Copeland, T.; Hale, C.; Sloan, R.P.; Sesso, H.D.; Manson, J.E.; Brickman, A.M. Multivitamin Supplementation Improves Memory in Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2023, 118, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Committee on the Return of Individual-Specific Research Results Generated in Research Laboratories (2018) In Returning Individual Research Results to Participants: Guidance for a New Research Paradigm, Downey AS, Busta ER, Mancher M, Botkin JR, eds., Washington (DC).

- Secretary's Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (2016) Attachment B: Return of Individual Research Results. Sharing Study Data and Results: Return of Individual Results. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Schroeder, K.; Bertelsen, N.; Scott, J.; Deane, K.; Dormer, L.; Nair, D.; Elliott, J.; Krug, S.; Sargeant, I.; Chapman, H.; Brooke, N. Building from Patient Experiences to Deliver Patient-Focused Healthcare Systems in Collaboration with Patients: A Call to Action. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2022, 56, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Hentz, J.G.; Shill, H.A.; Caviness, J.N.; Driver-Dunckley, E.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Sue, L.I.; Jacobson, S.A.; Belden, C.M.; Dugger, B.N. Low clinical diagnostic accuracy of early vs advanced Parkinson disease: clinicopathologic study. Neurology 2014, 83, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarztrauber, K.; Graf, E. Nonphysicians' and physicians' knowledge and care preferences for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2007, 22, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcalay, R.N.; Kehoe, C.; Shorr, E.; Battista, R.; Hall, A.; Simuni, T.; Marder, K.; Wills, A.M.; Naito, A.; Beck, J.C.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Nance, M. Genetic testing for Parkinson disease: current practice, knowledge, and attitudes among US and Canadian movement disorders specialists. Genet Med 2020, 22, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.R.; Stone, R.F.; Dan Ochs, V.; Litvan, I. Primary health care providers' knowledge gaps on Parkinson's disease. Educ Gerontol 2013, 39, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.H., Jr.; Cook-Deegan, R.M.; Hiraki, S.; Roberts, J.S.; Blazer, D.G.; Green, R.C. Genetic testing for Alzheimer's and long-term care insurance. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010, 29, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patient Protocol Engagement Toolkit,TransCelerate Biopharma Inc, https://www.transceleratebiopharmainc.com/ppet/planning-for-patient-engagement/, November 20, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).