Submitted:

20 December 2023

Posted:

20 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

A. Phytoplasmas Associated with Fruit Trees

1. Pome Fruit

1.1. Apple

1.2. Pear

2. Stone Fruit

2.1. Almond

2.2. Apricot

2.3. Peach and Nectarine

2.4. Plum

2.5. Sweet and Sour Cherry

B. Phytoplasmas Associated with Forest Trees

3.1. Sandal

3.2. Eucalyptus

3.3. Mulberry

3.4. Paulownia

3.5. Poplar

3.6. Elm

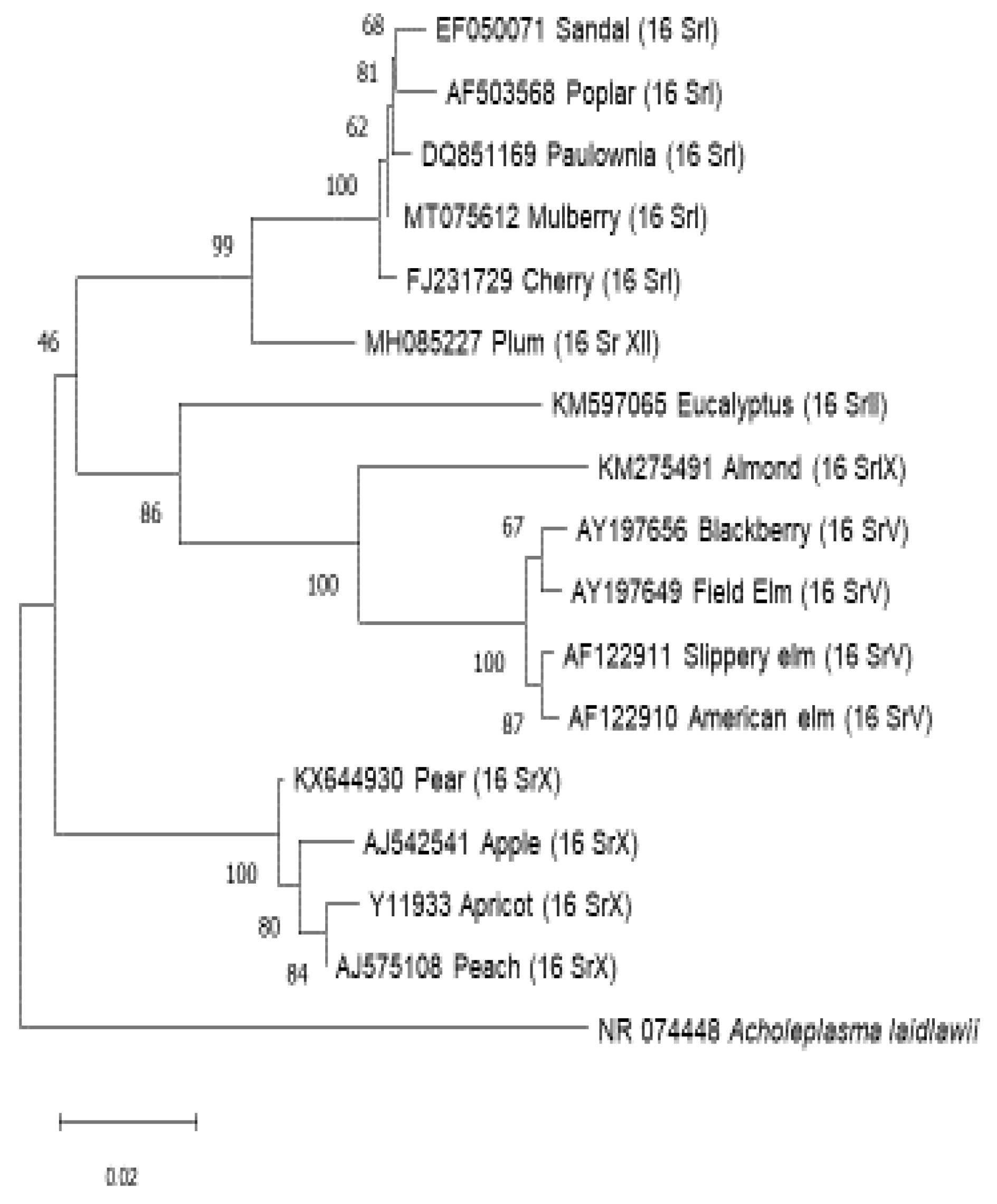

| S. No. | Name of Tree species | Common name | Location | Accession No. with Phytoplasma Group/ Subgroup |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

Malus domestica Borkh. (Rosaceae) |

Apple | Dossenheim, Germany | AJ542541 Candidatus Phytoplasma mali (16SrX) |

Seemüller and Schneider, 2004 |

| 2. |

Pyrus communis L. (Rosaceae) |

Pear | Chile | KX644930 Candidatus Phytoplasma pyri (16SrX-C) |

Facundo et al., 2017 |

| 3. |

Prunus dulcis(Mill.) D.A. Webb (Rosaceae) |

Almond | Lebanon | KM275491 Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium (16SrIX-B) |

Quaglino et al., 2015 |

| 4. |

Prunus armeniaca (Rosaceae) |

Apricot |

Czech Republic | Y11933 Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum (16SrX) |

Seemüller & Schneider, 2004 |

| 5. |

Prunus persica (Rosaceae) |

Peach | Spain | AJ575108 Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum (16SrX-B) |

Ludvíková et al., 2011 |

| 6. |

Prunus domestica (Rosaceae) |

Plum | Jordan | MH085227 Candidatus Phytoplasma solani (16SrXII) |

Salem et al., 2019 |

| 7. |

Prunus avium, and Prunus cerasus (Rosaceae) |

Sweet cherry, and Sour cherry |

Lithuania |

FJ231729 Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’-related strains (16SrI) |

Valiunas et al., 2009 |

| 8. |

Santalum spp. (Santalaceae) |

Sandal | India | EF050071 ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’-related strains (16SrI-B) |

Khan et al., 2008 |

| 9. |

Eucalyptus spp. (Myrtaceae) |

Eucalyptus | Brazil | KM597065 CandidatusPhytoplasma aurantifolia (16SrII-C) |

Neves de Souza et al., 2015 |

| 10. |

Morus spp. (Moraceae) |

Mulberry | Japan and Korea | MT075612 Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris (16SrI) |

Ji et al. 2009 |

| 11. |

Paulownia tomentosa (Paulowniaceae) |

Paulownia | China | DQ851169 Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris (16SrI-D) |

Yue et al., 2008 |

| 12. |

Populus spp. (Salicaceae) |

Poplar | Bulgaria Colombia France |

AF503568 Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris (16SrI-P) |

Šeruga et al., 2003 Perilla-Henao et al. 2012 |

| 13. |

Ulmus sp. (U. americana, U. rubra, U. minor) Rubus fruticosus |

American elm Slippery elm Field Elm Blackberry |

Ohio, New York, West Virginia and Italy |

AF122910, AF122911, AY197649, AY197656 Elm yellows group (16SrV) |

Griffiths et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2004Swingle , 1938 |

C. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beech, E.; Rivers, M.; Oldfield, S.; Smith, P. P. GlobalTreeSearch: The first complete global database of tree species and country distributions. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 2017 36(5), 454-489. [CrossRef]

- Olson, D. M.; Dinerstein, E.; Wikramanayake, E. D.; Burgess, N. D.; Powell, G. V.,Underwood, E. C. ;Kassem, K. R. Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth: A new global map of terrestrial ecoregions provides an innovative tool for conserving biodiversity. BioScience,2001 , 51(11), 933-938. [CrossRef]

- Crowther, T. W.; Glick, H. B.; Covey, K. R.;Bettigole, C.; Maynard, D. S.; Thomas, S. M.; Bradford, M. A. Mapping tree density at a global scale. Nature, 2015 ,525(7568), 201-205.

- Bar-On, Y. M., Phillips, R., & Milo, R. (2018). The biomass distribution on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(25), 6506-6511. [CrossRef]

- Fazan, L.; Song, Y. G.; Kozlowski, G. The woody planet: From past triumph to manmade decline. Plants, 2020, 9(11), 1593. [CrossRef]

- Davies, N. G.; Abbott, S.; Barnard, R. C.; Jarvis, C. I.; Kucharski, A. J.; Munday, J. D.; Edmunds, W. J. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B. 1.1. 7 in England. Science, 2021, 372(6538), eabg3055. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Chevallier, F.; Zhu, D.; Lian, J.; Canadell, J. G. The size of the land carbon sink in China. Nature, 2022, 603(7901), E7-E9. [CrossRef]

- Rao, G. P. Our understanding about phytoplasma research scenario in India. Indian phytopathology, 2021, 74(2), 371-401. [CrossRef]

- Oshima, K. Molecular biological study on the survival strategy of phytoplasma. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 2021, 87(6), 403-407. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhao, Y. Phytoplasma taxonomy: nomenclature, classification, and identification. Biology, 2022, 11(8), 1119. [CrossRef]

- Cardwell, G.; Bornman, J. F.; James, A. P.; Black, L. J. A review of mushrooms as a potential source of dietary vitamin D. Nutrients, 2018, 10(10), 1498. [CrossRef]

- Hogenhout, S. A.; Van der Hoorn, R. A.; Terauchi, R.; Kamoun, S. Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant-associated organisms. Molecular plant-microbe interactions,2009, 22(2), 115-122. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D. H.; Eichhorn, K. W.; Bleiholder, H.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Weber, EGrowth Stages of the Grapevine: Phenological growth stages of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera)—Codes and descriptions according to the extended BBCH scale. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research, 1995, 1(2), 100-103. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. M.; Gundersen-Rindal, D. E.;Bertaccini, APhytoplasma: ecology and genomic diversity. Phytopathology, 1998, 88(12), 1359-1366. [CrossRef]

- Jarausch, W.; Lansac, M.; Saillard, C.;Broquaire, J. M.;Dosba, F. PCR assay for specific detection of European stone fruit yellows phytoplasmas and its use for epidemiological studies in France. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 1998, 104, 17-27. [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Loi, N.; Ermacora, P.; Carraro, L.; Pastore, M. A real-time PCR method for detection and quantification ofCandidatus Phytoplasma prunorum'in its natural hosts. Bulletin of Insectology, 2007, 60(2), 251.

- Yvon, M.; Thébaud, G.; Alary, R.; Labonne, G.Specific detection and quantification of the phytopathogenic agent ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum’. Molecular and Cellular Probes, 2009, 23(5), 227-234. [CrossRef]

- Pignatta, D.; PoggiPollinI, C.; Giunchedi, L.; Ratti, C.; Reggiani, N.; Forno, F.; Pelato, E. A real-time PCR assay for the detection of European Stone Fruit Yellows Phytoplasma (ESFYP) in plant propagation material. In Acta horticulturae-Proceedings of the 20th International symposium on virus and virus-like diseases of temperate fruit crops-Fruit virus diseases 2008 (Vol. 781, pp. 499-503).

- Thébaud, G.; Yvon, M..; Alary, R.,; Sauvion, N.; Labonne, G. Efficient transmission of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum’is delayed by eight months due to a long latency in its host-alternating vector. Phytopathology, 2009, 99(3), 265-273. [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, G.; Zlatkovic, S.; Cakic, M.; Cakic, S.; Lacnjevac, C.; Rajic, Z. Fast fourier transform IR characterization of epoxy GY systems crosslinked with aliphatic and cycloaliphatic EH polyamine adducts. Sensors, 2010, 10(1), 684-696. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M. A.; Dangl, J. L. Functions of the respiratory burst oxidase in biotic interactions, abiotic stress and development. Current opinion in plant biology, 2005, 8(4), 397-403. [CrossRef]

- De Jonghe, K.; De Roo, I.; Maes, M. Fast and sensitive on-site isothermal assay (LAMP) for diagnosis and detection of three fruit tree phytoplasmas. European journal of plant pathology, 2017, 147, 749-759. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. M.; Lin, Y. C.; Li, J. R.; Chien, Y. Y.; Wang, C. J.; Chou, L.; Yang, J. Y. Accelerating complete phytoplasma genome assembly by immunoprecipitation-based enrichment and MinION-based DNA sequencing for comparative analyses. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2021, 12, 766221. [CrossRef]

- Seemüller, E.; Schneider, B. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’,‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pyri’and ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum’, the causal agents of apple proliferation, pear decline and European stone fruit yellows, respectively. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2004, 54(4), 1217-1226. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. M.; Gundersen-Rindal, D. E.; Bertaccini, A. Phytoplasma: ecology and genomic diversity. Phytopathology, 1998, 88(12), 1359-1366. [CrossRef]

- Fránová, J.;Špak, J.; Šimková, M. First report of a 16SrIII-B subgroup phytoplasma associated with leaf reddening, virescence and phyllody of purple coneflower. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2013, 136, 7-12.

- Cieślińska, M.; Hennig, E.; Kruczyńska, D.;Bertaccini, A. Genetic diversity of'Candidatos Phytoplasma mali'strains in Poland. PhytopathologiaMediterranea, 2015, 477-487. [CrossRef]

- Seemüller, E.; Sule, S.; Kube, M.; Jelkmann, W.; Schneider, B. The AAA+ ATPases and HflB/FtsH proteases of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’: phylogenetic diversity, membrane topology, and relationship to strain virulence. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2013, 26(3), 367-376. [CrossRef]

- Janik, K.; Panassiti, B.; Kerschbamer, C.; Burmeister, J.; Trivellone, V. Phylogenetic Triage and Risk Assessment: How to Predict Emerging Phytoplasma Diseases. Biology, 2023, 12(5), 732. [CrossRef]

- Kingston-Smith, A.; Wilkins, P. W.; Humphreys, M. O. Leaves of high yielding perennial ryegrass contain less aggregated Rubisco than S23. Molecular breeding for the genetic improvement of forage crops and turf, 2005, 227, 113. [CrossRef]

- Barthel, D.; Cullinan, C.; Mejia-Aguilar, A.; Chuprikova, E.; McLeod, B. A.; Kerschbamer, C.; Janik, K. Identification of spectral ranges that contribute to phytoplasma detection in apple trees–A step towards an on-site method. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2023, 303, 123246. [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, M.; Śliwa, H. First report of phytoplasma belonging to apple proliferation group in roses in Poland. Plant Disease, 2004, 88(11), 1283-1283. [CrossRef]

- Mehle, N.; Ravnikar, M.; Seljak, G.; Knapic, V.; Dermastia, M. The most widespread phytoplasmas, vectors and measures for disease control in Slovenia. Phytopathogenic mollicutes, 2011, 1(2), 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Musetti, R. Management and ecology of phytoplasma diseases of grapevine and fruit crops. In Integrated management of diseases caused by fungi, phytoplasma and bacteria 2008(pp. 43-60). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.; Alma, A. Candidatus Phytoplasma mali': the current situation of insect vectors in northwestern Italy. Bulletin of Insectology, 2007, 60(2), 187.

- Jarausch, B.; Fuchs, A.; Schwind, N.; Krczal, G.; Jarausch, W. Cacopsyllapicta as most important vector for ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’in Germany and neighbouring regions. Bulletin of Insectology, 2007, (2), 189-190.

- Mayer, D. M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.; Bardes, M.; Salvador, R. B. How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 2009, 108(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Carraro, L.; Loi, N.; Ermacora, P. Transmission characteristics of the European stone fruit yellows phytoplasma and its vector Cacopsyllapruni. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2001, 107, 695-700.

- Blomquist, C. L.; Kirkpatrick, B. C. Frequency and seasonal distribution of pear psylla infected with the pear decline phytoplasma in California pear orchards. Phytopathology, 2002, 92(11), 1218-1226. [CrossRef]

- Facundo, R.; Quiroga, N.; Méndez, P.; Zamorano, A.; Fiore, N. First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pyri’on pear in Chile. Plant Disease, 2017, 101(5), 830-830. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi-Tameh, M.; Bahar, M.;Zirak, L. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ and ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma aurantifolia’, new phytoplasma species infecting apple trees in Iran. Journal of Phytopathology, 2014, 162(7-8), 472-480. [CrossRef]

- Seemüller, E.; Marcone, C.; Lauer, U.; Ragozzino, A.; Göschl, M. Current status of molecular classification of the phytoplasmas. Journal of plant pathology,1998, 3-26.

- Etropolska, A;Jarausch, W;Jarausch, B;Trenchev, G. Detection of European fruit tree phytoplasmas and their insect vectors in important fruit-growing regions in Bulgaria. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science. 2015, 21(6):1248-53.

- Seemüller,E; Kampmann, M; Kiss , E; Schneider, B. HflB gene-based phytopathogenic classification of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’strains and evidence that strain composition determines virulence in multiply infected apple trees. Molecular plant-microbe interactions. 2011 , 24(10):1258-66. [CrossRef]

- Koch, K. Sucrose metabolism: regulatory mechanisms and pivotal roles in sugar sensing and plant development. Current opinion in plant biology. 2004 , 1;7(3):235-46. [CrossRef]

- Kaviani , Rad, A.; Balasundram, S.K; Azizi , S.; Afsharyzad, Y.; Zarei, M.; Etesami, H.; Shamshiri, R. R. An overview of antibiotic resistance and abiotic stresses affecting antimicrobial resistance in agricultural soils. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 , 12;19(8):4666. [CrossRef]

- Zirak, L.; Bahar, M.; Ahoonmanesh, A. Characterization of phytoplasmas related to ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ and peanut WB group associated with sweet cherry diseases in Iran. Journal of Phytopathology. 2010 , 158(1):63-5. [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.H.; Chen , S.H.; Wu , H. H.; Ho, C.W.; Ko , M.T.; Lin, C. Y. CytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC systems biology. 2014, 8(4):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Vyas ,S. R.; Chakravorty, S.C. Wines from Indian grapes. Haryana Agricultural University; 1971.

- Joshi ,V.K.; Sandhu, D.K.; Jaiswal, S. Effect of addition of SO sub (2) on solid-state fermentation of apple pomace. Current science. Bangalore. 1995;69(3):263-4.

- Giunchedi, L.; Marani, F.; Credi ,R. Mycoplasma-like bodies associated with Plum decline (leptonecrosis)/Corpiriferibili a micoplasmiassociait al deperimento del Susino (leptonecrosi). Phytopathologiamediterranea. 1978, 1:205-9.

- Morvan, G. Apricot chlorotic leaf roll. EPPO Bulletin. 1977;7(1):37-55. [CrossRef]

- Pollini , C.P.; Giunchedi, L; Gambin, E. Presence of mycoplasma-like organisms in peach trees in Northern-Central Italy. PhytopathologiaMediterranea. 1993 ,1:188-92. [CrossRef]

- Lederer, W.; Seemüller, E. Demonstration of mycoplasmas in Prunus species in Germany. Journal of Phytopathology. 1992 ,134(2):89-96. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz ,M,G.; Wackernagel, W. Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment. Microbiological reviews. 1994, ;58(3):563-602. [CrossRef]

- Navrátil , M.; Šturdík, E.; Gemeiner, P. Batch and continuous mead production with pectate immobilised, ethanol-tolerant yeast. Biotechnology Letters. 2001, 23:977-82. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Fernández ,A.; García-Laviña, P.; Fidalgo ,C.; Abadía, J,.; Abadía, A. Foliar fertilization to control iron chlorosis in pear (Pyrus communis L.) trees. Plant and Soil. 2004 , 263:5-15.

- Carraro ,L.; Ferrini, F.; Labonne, G.; Ermacora, P.; Loi , N. Seasonal infectivity of Cacopsyllapruni, vector of European stone fruit yellows phytoplasma. Annals of Applied Biology. 2004, 144(2):191-5. [CrossRef]

- Jarausch,W.; Jarausch-Wehrheim, B.; Danet, J.L.; Broquaire, J.M.; Dosba, F.; Saillard,C; Garnier , M. Detection and indentification of European stone fruit yellows and other phytoplasmas in wild plants in the surroundings of apricot chlorotic leaf roll-affected orchards in southern France. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2001 ,107:209-17. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Asencio ,J.; Wojciechowska, K.; Baskerville , M.; Gomez, A. L.; Perry , K. L.; Thompson, J.R. The complete nucleotide sequence and genomic characterization of grapevine asteroid mosaic associated virus. Virus Research. 2017 , 2;227:82-7. [CrossRef]

- Duduk ,B.; Botti ,S.; Ivanović , M.; Krstić, B.; Dukić ,N.; Bertaccini,A. Identification of phytoplasmas associated with grapevine yellows in Serbia. Journal of Phytopathology. 2004 , 152(10):575-9. [CrossRef]

- Fialova, R.; Navratil, M.; Lauterer, P.; Navrkalova, V. Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum': the phytoplasma infection of Cacopsyllapruni from apricot orchards and from overwintering habitats in Moravia (Czech Republic). Bulletin of Insectology. 2007 , 1;60(2):183.

- Gupta ,S; Handa, A.; Brakta,A.; Negi , G.; Tiwari, R.K.; Lal ,M. K.; Kumar , R. First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ associated with yellowing, scorching and decline of almond trees in India. PeerJ.2023 , 28;11:e15926.

- Verdin , E.; Salar , P.; Danet ,J.L.; Choueiri, E.; Jreijiri, F.; El Zammar , S.; Gelie, B.; Bove, J.M.; Garnier, M. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’sp. nov., a novel phytoplasma associated with an emerging lethal disease of almond trees in Lebanon and Iran. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2003 , 53(3):833-8. [CrossRef]

- Salehi ,M.; Izadpanah, K.; Almond Brooming. InProceedings of the 12th Iranian Plant Protection Congress 2 7 September 1995 Karadj 1995.

- Abou-Jawdah ,Y.; Dakhil, H.; El-Mehtar, S.; Lee, I.M. Almond witches'-broom phytoplasma: a potential threat to almond, peach, and nectarine. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology. 2003 ,1;25(1):28-32. [CrossRef]

- Lova, M.M.; Quaglino, F.; Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Choueiri ,E.; Sobh, H.; Casati ,P.; Tedeschi, R.; Alma , A.; Bianco, P.A. Identification of new 16SrIX subgroups,-F and-G, among'Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium'strains infecting almond, peach and nectarine in Lebanon. Phytopathologiamediterranea. 2011, 1;50(2):273-82.

- Choueiri , E.; Verdin ,E.; Danet ,J. L.; Jreijiri,F.; El Zammar, S.; Salard , P.; Bové, J.M.; Garnier ,M. A Phytoplasma Disease Of Almond In Lebanon. Options Méditerranéennes: Série B. Etudes et Recherches. 2003(45):123-5.

- Salehi, M.; Izadpanah, K.; Heydarnejad, J. Characterization of a new almond witches’ broom phytoplasma in Iran. Journal of Phytopathology. 2006 ;154(7-8):386-91. [CrossRef]

- Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Sobh, H.; Akkary,M. First report of Almond witches’ broom phytoplasma 1 (‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’) causing a severe disease on nectarine and peach trees in Lebanon. EPPO bulletin. 2009 ,39(1):94-8. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Salehi, E.; Abbasian, M.; Izadpanah, K. Wild almond (Prunus scoparia), a potential source of almond witches’ broom phytoplasma in Iran. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2015 1;97(2):377-81.

- Quaglino, F; Kube, M.; Jawhari.; M.; Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Siewert , C.; Choueiri, E.; Sobh, H.; Casati, P.; Tedeschi.; R.; Lova ,M. M.; Alma, A. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’associated with almond witches’-broom disease: from draft genome to genetic diversity among strain populations. BMC microbiology. 2015 15:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Casati ,P.; Quaglino, F.; Abou-Jawdah ,Y.; Picciau, L.; Cominetti, A.; Tedeschi , R.; Jawhari, M.; Choueiri , E.; Sobh , H.; Lova , M. M.; Beyrouthy, M. Wild plants could play a role in the spread of diseases associated with phytoplasmas of pigeon pea witches'-broom group (16SrIX). Journal of Plant Pathology. 2016 , 1:71-81.

- Torres, E.; Martin, M. P.; Paltrinieri , S.; Vila, A.; Masalles, R.; Bertaccini, A. Spreading of ESFY phytoplasmas in stone fruit in Catalonia (Spain). Journal of Phytopathology. 2004, 152(7):432-7. [CrossRef]

- Sertkaya ,G.; Martini , M.; Ermacora , P.; Musetti, R.; Osler , R. Detection and characterization of phytoplasmas in diseased stone fruits and pear by PCR-RFLP analysis in Turkey. Phytoparasitica. 2005 , 33:380-90. [CrossRef]

- Mehle, N.; Ravnikar, M.; Seljak, G.; Knapic, V.; Dermastia, M. The most widespread phytoplasmas, vectors and measures for disease control in Slovenia. Phytopathogenic mollicutes. 2011;1(2):65-76. [CrossRef]

- Tarca ,A.L.; Bhatti ,G.; Romero, R. A comparison of gene set analysis methods in terms of sensitivity, prioritization and specificity. PloS one. 2013 ,15;8(11):e79217. [CrossRef]

- Žežlina, I.; Rot, M.; Kač, M.; Trdan, S. Causal agents of stone fruit diseases in Slovenia and the potential for diminishing their economic impact–a review. Plant Protection Science. 2016 , 28;52(3):149-57. [CrossRef]

- Gentit, P.; Delbos, R. P.; Candresse, T.; Dunez, J. Characterization of a new nepovirus infecting apricot in Southeastern France: apricot latent ringspot virus. European journal of plant pathology.2001 , 107:485-94. [CrossRef]

- Kison , H.; Seemüller , E. Differences in strain virulence of the European stone fruit yellows phytoplasma and susceptibility of stone fruit trees on various rootstocks to this pathogen. Journal of Phytopathology. 2001 , 4;149(9):533-41. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pastor, A.; Domingo , R.; Torrecillas , A.; Ruiz-Sánchez , M. C. Response of apricot trees to deficit irrigation strategies. Irrigation Science. 2009, 27:231-42. [CrossRef]

- Genini, M.; Ramel , M. E. Distribution of European stone fruit yellows phytoplasma in apricot trees in Western Switzerland. InXIX International Symposium on Virus and Virus-like Diseases of Temperate Fruit Crops-Fruit Tree Diseases 657 2003 , 21 (pp. 455-458).

- Koncz , L.S.; Petróczy, M.; Pénzes, B.; Ladányi, M.; Palkovics , L.; Gyócsi, P.; Nagy , G.; Ágoston, J.; Fail , J. Detection of ‘CandidatusPhythoplasmaprunorum’in Apricot Trees and its Associated Psyllid Samples. Agronomy. 2023 , 9;13(1):199. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.H.; Dosba, F.; Poggi-Pollini, C.; Llacer, G.; Seemüller, E. Phytoplasma diseases of Prunus species in Europe are caused by genetically similar organisms/Phytoplasma-Krankheit von Prunus-Arten in Europa werdendurchgenetischeinheitlicheOrganismenhervorgerufen. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenkrankheiten und Pflanzenschutz/Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection. 1994 ,1:567-75.

- Delic ,D.; Martini ,M.; Ermacora , P.; Myrta , A.; Carraro, L. Identification of fruit tree phytoplasmas and their vectors in Bosnia and Herzegovina. EPPO bulletin. 2007 , 37(2):444-8. [CrossRef]

- Ambrožič Turk, B.; Stopar , M.; Fajt , N. Blossom thinning of'Redhaven'peach in Slovenia. InXXVIII International Horticultural Congress on Science and Horticulture for People (IHC2010): International Symposium on Plant 932 2010 , 22 (pp. 251-254).

- Cieślińska, M.; Morgaś, H. Detection and identification of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum’,‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’and ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pyri’in stone fruit trees in Poland. Journal of Phytopathology. 2011,159(4):217-22. [CrossRef]

- Ludvikova,H.; Franova, J.; Sucha , J. Phytoplasmas in apricot, peach and sour cherry orchards in East Bohemia, Czech Republic. Bulletin of Insectology. 2011, 64(Supplement):S67-8. [CrossRef]

- Mehle ,N.; Ravnikar, M.; Seljak, G.; Knapic, V, Dermastia M. The most widespread phytoplasmas, vectors and measures for disease control in Slovenia. Phytopathogenic mollicutes. 2011;1(2):65-76.

- Bodnár, D.; Csüllög, K.; Tarcali,G. Review of the biology of plant psyllid (Cacopsyllapruni, Scopoli 1763), and its role in the spreading of European stone fruit yellows, ESFY-phytoplasma with Hungarian data. Acta AgrariaDebreceniensis. 2018, 30(74):25-33. [CrossRef]

- Etropolska,A.; Lefort , F. First report of candidatus phytoplasma prunorum, the european stone fruit yellows phytoplasma on peach trees on the territory of canton of Geneva, Switzerland. International Journal of Phytopathology. 2019 , 30;8(2):63-7. [CrossRef]

- Ermacora, P.; Loi, N.; Ferrini , F, Loschi, A, Martini M, Osler R, Carraro L. Hypo-and hyper-virulence in apricot trees infected by European stone fruit yellows. Julius-Kühn-Archiv (427). 2010 , 29:197-200.

- Marcone,C; Guerra, L.J.; Uyemoto, J. K. Phytoplasmal diseases of peach and associated phytoplasma taxa. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2014 , 1;96(1).

- Ragozzino ,A. CHAPTER 46: Peach Rosette Phytoplasma. InVirus and Virus-Like Diseases of Pome and Stone Fruits 2011 (pp. 251-253). The American Phytopathological Society.

- Salehi, M.; Hosseini , S. A.; Salehi , E.; Quaglino, F.; Bianco, P.A. Peach witches’-broom, an emerging disease associated with ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’and ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma aurantifolia’in Iran. Crop protection. 2020 ,1;127:104946. [CrossRef]

- Dosba, F.; Orliac , S.; Dutrannoy, F.; Maison , P.; Massonià , G.; Audergon, J. M. Evaluation of resistance to plum pox virus in apricot trees. InXVInternational Symposium on Fruit Tree Diseases 309 1991 , 8 (pp. 211-220). [CrossRef]

- Landi ,F.; Prandini , A.; Paltrinieri , S.; Missere,D.; Bertaccini, A. Susceptibility to European stone fruit yellows phytoplasma of new and old plum varieties. InCurrent status and perspectives of phytoplasma disease research and management. 2010 (pp. 84-84).

- Pollini, C.P.; Bissani, R.; Giunchedi,L.; Vindimian, E. Occurrence of phytoplasma infection in European plums (Prunus domestica). Journal of Phytopathology. 1995 , 143(11-12):701-3. [CrossRef]

- Sauvion, N.; Lachenaud, O.; Genson , G.; Rasplus J, Labonne, G. Are there several biotypes of Cacopsyllapruni?.Bulletin of Insectology. 2007 , 1;60(2):185.

- Peccoud, J.; Labonne .G.; Sauvion,N. Molecular test to assign individuals within the Cacopsyllapruni complex. PLoS One. 2013 , 19;8(8):e72454. [CrossRef]

- Paltrinieri, S.; Bertaccini, A.; Lugli , A.; Monari , W. Three years of molecular monitoring of phytoplasma spreading in a plum growing area in Italy. InXIX International Symposium on Virus and Virus-like Diseases of Temperate Fruit Crops-Fruit Tree Diseases 657 2003 , 21 (pp. 501-506). [CrossRef]

- Salem ,A. E.; Naweto, M.; Mostafa ,M, Authority AE. Combined effect of gamma irradiation and chitosan coating on physical and chemical properties of plum fruits. Journal of Nuclear Technology in Applied Science. 2016;4:91-102.

- Bertaccini,A.; Duduk, B.; Paltrinieri ,S.; Contaldo, N. Phytoplasmas and phytoplasma diseases: a severe threat to agriculture. American Journal of Plant Sciences. 2014 , 27;2014. [CrossRef]

- Bernhard ,R.; Marenaud, C.; Eymet, J.; Sechet, J.; Fos, A.; Moutous, G. A complex disease of certain Prunus:'Molieres decline'. ComptesRendus des Seances de l'Academied'Agriculture de France. 1977;3(3):178-88.

- Davis , R.E.; Dally , E.L.; Zhao, Y.; Lee, I.M.; Wei, W.; Wolf, T. K.; Beanland , L.; LeDoux , D.G.; Johnson, D.A.; Fiola, J.A.; Walter-Peterson , H. Unraveling the Etiology of North American Grapevine Yellows (NAGY): Novel NAGY Phytoplasma Sequevars Related to ‘Candidatu s Phytoplasma pruni’. Plant Disease. 2015 5;99(8):1087-97. [CrossRef]

- Uyemoto,J.K.; Kirkpatrick, B.C. CHAPTER 44: X-Disease Phytoplasma. InVirus and Virus-Like Diseases of Pome and Stone Fruits 2011 (pp. 243-245). The American Phytopathological Society.

- Kirkpatrick, M.; Lofsvold, D.; Bulmer ,M. Analysis of the inheritance, selection and evolution of growth trajectories. Genetics.1990 , 1;124(4):979-93. [CrossRef]

- Arocha Rosete, Y.; To, H.; Evans, M.; White , K.; Saleh , M.; Trueman , C.; Tomecek , J.; Van Dyk , D.; Summerbell , R.C.; Scott , J.A. Assessing the use of DNA detection platforms combined with passive wind-powered spore traps for early surveillance of potato and tomato late blight in Canada. Plant Disease. 2021 30;105(11):3610-22. [CrossRef]

- Risto ,A.; Abdalla , M.; Myrelid, P. Staging Pouch Surgery in Ulcerative Colitis in the Biological Era. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 2022 , 17;35(01):058-65. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; Méndez, J.; Guijarro,J. A. Molecular virulence mechanisms of the fish pathogen Yersinia ruckeri. Veterinary microbiology. 2007 ,15;125(1-2):1-0. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, H.M.; Sinclair, W.A.; Boudon-Padieu, E.; Daire, X.; Lee, I.M.; Sfalanga, A.; Bertaccini, A. Phytoplasmas associated with elm yellows: molecular variability and differentiation from related organisms. Plant Disease. 1999;83(12):1101-4. [CrossRef]

- Marcone, C.; Valiunas, D.; Mondal, S.; Sundararaj, R. On some significant phytoplasma diseases of forest trees: an update. Forests. 2021;12(4):408. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Balasundaran, M. Detection of sandal spike phytoplasma by polymerase chain reaction. Current science. 1999;76(12):1574-6.

- Khan, J.A.; Srivastava, P.; Singh, S.K. Identification of a ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’-related strain associated with spike disease of sandal (Santalum album) in India. Plant Pathology. 2006;55(4):572. [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.A.; Singh, S.K.; Ahmad, J. Characterisation and phylogeny of a phytoplasma inducing sandal spike disease in sandal (Santalum album). Annuals of Applied Biology. 2008;153(3):365-72. [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.S.; Muniyappa, V. Epidemiology of sandal spike-disease. Tree Mycoplasmas and Mycoplasma Diseases; Hiruki, C., Ed.; University of Alberta Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada. 1988:57-8.

- Marcone, C.; Lee, I.M.; Davis, R.E.; Ragozzino, A.; Seemüller, E. Classification of aster yellows-group phytoplasmas based on combined analyses of rRNA and tuf gene sequences. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2000;50(5):1703-13. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.M.; Martini, M.; Marcone, C.; Zhu, S.F. Classification of phytoplasma strains in the elm yellows group (16SrV) and proposal of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma ulmi’for the phytoplasma associated with elm yellows. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2004;54(2):337-47. [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, P.G.; Beanland, L. Insect vectors of phytoplasmas. Annu. Rev. Entomol.2006;51:91-111. [CrossRef]

- Tiwarekar, B.; Kirdat, K.; Sundararaj, R.; Yadav, A. Updates on phytoplasma diseases associated with sandalwood in Asia. In: Phytoplasma Diseases of Major Crops, Trees, and Weeds. Elsevier; 2023.309–20. [CrossRef]

- Sastry, K.S.; Thakur, R.N.; Gupta, J.H.; Pandotra, V.R. Three virus diseases of Eucalyptus citriodora. Indian Phytopathology. 1971.

- Marcone, C. Current status of phytoplasma diseases of forest and landscape trees and shrubs. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2015;1.9-36.

- Marcone, C.; Ragozzino, A.; Seemuller, E. Detection of an elm yellows-related phytoplasma in eucalyptus trees affected by little-leaf disease in Italy. Plant Disease. 1996, 80, 669–673.

- Neves de Souza, A.; Leão de Carvalho, S.; Nascimento da Silva, F.; Alfenas, A.C.; Zauza, E.A.; Carvalho. C.M. First report of phytoplasma associated with Eucalyptus urophylla showing witches’ broom in Brazil. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes. 2015;5(1s):S83-4. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Hosseini, S.E.; Salehi, E. First report of a ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ related phytoplasma associated with eucalyptus little leaf disease in Iran. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2016;98(1):175.

- Azimi, M.; Farokhi-Nejad, R.; Mehrabi-Koushki, M. First report of a ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma aurantifolia’-related strain associated with leaf roll symptoms on eucalyptus in Iran. New Disease Reports. 2017;35(4):3. [CrossRef]

- Baghaee-Ravari, S.; Jamshidi, E.; Falahati-Rastegar, M. “Candidatus Phytoplasma solani” associated with Eucalyptus witches’ broom in Iran. Forest Pathology. 2018;48(1):e12394. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, B. R.; Freitas, I. A. S.; de Araujo Lopes, V.; do Rosario Rosa, V.; Matos, F. S. Growth of Eucalyptus plants irrigated with saline water. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 2015;10(10), 1091-1096.

- Dhanyalakshmi, K.H.; Nataraja, K.N. Mulberry (Morus spp.) has the features to treat as a potential perennial model system. Plant signaling&behavior. 2018;13(8):e1491267. [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Gai, Y.; Zheng, C.; Mu, Z. Comparative proteomic analysis provides new insights into mulberry dwarf responses in mulberry (Morus alba L.). Proteomics. 2009;9(23):5328-39. [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.O.; Teranaka, M.; Yora, K.; Asuyama, H. Mycoplasma-or PLT group-like microorganisms found in the phloem elements of plants infected with mulberry dwarf, potato witches' broom, aster yellows, or paulownia witches' broom. Japanese Journal of Phytopathology. 1967;33(4):259-66. [CrossRef]

- Ishiie, T.; Doi, Y.; Yora, K.; Asuyama, H. Suppressive effects of antibiotics of tetracycline group on symptom development of mulberry dwarf disease. Japanese Journal of Phytopathology. 1967;33(4):267-75. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; La, Y.J.; Kim, Y.T. Transmission and histochemical detection of mulberry dwarf mycoplasma in several herbaceous plants. The Plant Pathology Journal. 1985;1(3):184-9.

- Yuan-zhang, K.; Feng-ping, Z.; Zhi-song, X.; Pei-gen, C. Studies on the mechanism of mulberry varietal resistance to mulberry yellow dwarf disease. International Journal of Tropical Plant Diseases. 1999;17(1-2):103-14.

- Luo, L.; Zhang, X.; Meng, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J. Draft genome sequences resources of mulberry dwarf phytoplasma strain MDGZ-01 associated with mulberry yellow dwarf (MYD) diseases. Plant Disease. 2022;106(8):2239-42. [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.N.; Wu, Y.F.; Shi, Y.Z.; Wu, K.K.; Li, Y.R. First report of paulownia witches'-broom phytoplasma in China. Plant disease. 2008;92(7):1134-. [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Asuyama, H. Paulownia witches'broom disease. In Mycoplasma diseases of trees and shrubs. 1981 (pp. 135-145). Academic Press.

- Hiruki, C.Paulownia witches’-broom disease important in East Asia. Acta Horticulture. 1999;469: 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, P. G.; Beanland, L. Insect vectors of phytoplasmas. Annu. Rev. Entomol., 2006 , 51, 91-111. [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Dong, Y.; Xu, S.; Huang, S.; Zhai, X.; Fan, G. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression of the Paulownia fortunei MADS-Box Gene Family in Response to Phytoplasma Infection. Genes. 2023;14(3):696. [CrossRef]

- Atanasoff, D. Stammhexenbesenbei Ulmen und anderenBäumen. Archives of Phytopathology & Plant Protection. 1973;9(4):241-3. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meer, F.A. Witches' brooms in poplars?.Populier. 1980;17(2):42-3.

- Cousin, M.T.; Sharma, A.K. Mycoplasmalike Organisms (MLOs) Associated With the Witches' Broom Disease of Poplar. PhytopathologischeZeitschrift. 1986;117(4). [CrossRef]

- Seemüller, E.; Lederer, W. MLO-associated decline of Alnus glutinosa, Populus tremula and Crataegus monogyna. Journal of Phytopathology. 1988;121(1):33-9. [CrossRef]

- Cousin, M.T. Witches' broom: a phytoplasma disease of poplar.1996.

- Berges, R.; Cousin, M.T.; Roux, J.; Mäurer R.; Seemüller, E. Detection of phytoplasma infections in declining Populus nigra ‘Italica’trees and molecular differentiation of the aster yellows phytoplasmas identified in various Populus species. European journal of forest pathology. 1997;27(1):33-43. [CrossRef]

- Šeruga, M.; Škorić, D.; Botti, S.; Paltrinieri, S.; Juretić, N.; Bertaccini, A.F. Molecular characterization of a phytoplasma from the aster yellows (16SrI) group naturally infecting Populus nigra L.‘Italica’trees in Croatia. Forest pathology. 2003;33(2):113-25. [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, J.; Paltrinieri, S.; Contaldo, N.; Bertaccini, A.; Duduk, B. Occurrence of two ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’-related phytoplasmas in poplar trees in Serbia. Bulletin of Insectology. 2011;64(Supplement):S57-8.

- Cousin, M.T.; Roux, J.; Boudon-Padieu, E.; Berges, R.; Seemuller, E.; Hiruki, C. Use of heteroduplex mobility analysis (HMA) for differentiating phytoplasma isolates causing witches’ broom disease on Populus nigra cv italica and stolbur or big bud symptoms on tomato. Journal of Phytopathology. 1998;146(2-3):97-102. [CrossRef]

- Perilla-Henao, L.M.; Dickinson, M.; Franco-Lara, L. First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ affecting woody hosts (Fraxinus uhdei, Populus nigra, Pittosporum undulatum, and Croton spp.) in Colombia. Plant Disease. 2012;96(9):1372-. [CrossRef]

- Marcone, C. Elm yellows: A phytoplasma disease of concern in forest and landscape ecosystems. Forest Pathology. 2017;47(1):e12324. [CrossRef]

- Swingle, R.U. A phloem necrosis of Elm. Phytopathology. 1938;28(10).

- Jacobs, K.A.; Lee, I.M.; Griffiths, H.M.; MillerJr, F.D.; Bottner, K.D. A new member of the clover proliferation phytoplasma group (16SrVI) associated with elm yellows in Illinois. Plant Disease. 2003;87(3):241-6. [CrossRef]

- Matteoni, J.A.; Sinclair, W.A. Elm yellows and ash yellows. Tree mycoplasmas and mycoplasma diseases. 1988:19-31.

- Mittempergher, L. Elm yellows in Europe. InThe elms: Breeding, conservation, and disease management.2000:103-119. Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Marcone, C. Current status of phytoplasma diseases of peach. InVIII International Peach Symposium1084. 2013:569-578. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).