1. Introduction

The greatest hazard to public health in the twenty-first century is greenhouse gas emissions which lead to global warming and climate change (Singh & Purohit, 2014). California is the second largest greenhouse gas emitter in the U.S. (Perez et al., 2020), with its transportation sector accounting for the highest share of emissions. To comply with federal air quality regulations and climate change targets, the State of California has taken substantial steps, in the form of mandates, to convert medium-duty (MD) and heavy-duty (HD) trucks to low-carbon transportation alternatives. (Gordon et al., 2022). Low-carbon transportation modes are defined by their minimal energy consumption, which supports sustainable urban development and greenhouse gas reduction (primarily CO2) (Cao et al., 2023). The California Air Resources Board (CARB) developed several models to cut emissions by mandating low-carbon transportation (LCT) adoption in specific sectors. To facilitate compliance with such mandates in the on-road sector, the Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Project (HVIP) was established by CARB to provide vouchers that lower the upfront cost of clean trucks (California Air Resources Board, 2023). Similarly, to encourage the off-road equipment (ORE) sector to adopt zero-emission vehicles, several incentive and regulatory programs were introduced, such as the Clean Off-Road Equipment (CORE) Voucher Incentive Project (Gordon et al., 2022), Agricultural Replacement Measures for Emission Reductions (FARMER) Program (Mccullough et al., 2021), In-Use Off-Road Diesel-Fueled Fleets Regulation (Huang & Fan, 2022), etc.

Given the emerging importance of LCT in recent years, several studies in Europe sought to analyze the determinants of alternative fuel vehicle (AFV) adoption in HDV sectors. Performing a choice experiment in Switzerland and Germany, (Walter et al., 2012) discovered that two financial determinants namely, the vehicle purchase price, and operating costs, had the greatest impact on the decision to purchase. Another German study (Seitz et al., 2015), found that corporate social responsibility with environmental attitudes can also have a profound influence on the choice of CO2-reducing powertrain technologies. By employing a Delphi study, (Anderhofstadt & Spinler, 2019) found that the availability of fueling or charging infrastructure, the ability to enter low-emission zones, current and projected fuel costs, are crucial considerations while adopting alternative fuel-powered HDTs.

Some studies in the US also sought to identify the determinants of AFV adoption in HDV sectors. A study from 2014 found three motivating rationales namely, first-mover advantage, specialized functional capabilities, and a desire to build an appealing business brand (Sierzchula, 2014). By conducting a series of in-depth qualitative interviews in California, USA, a more recent study (Bae et al., 2022) detected 38 motivators or barriers (including functional suitability, monetary costs, fuel infrastructures, and reliability/safety of the vehicles and engines) of AFV adoption in the HDV sectors.

Since past research has consistently identified cost components as important determinants of LCT adoption, CARB introduced several monetary incentives for electric vehicle fleets, many in the form of vouchers for MD and HD sectors (Burke & Miller, 2020; Jin et al., 2014). These vouchers level the playing field of LCT with conventional technologies in terms of cost. However, due to a lack of infrastructural or financial backing, many fleet operators may be ignorant or hold incorrect impressions about LCT and their incentive programs. A noticeable knowledge gap exists within the literature concerning these behavioral factors (awareness and impression of LCT and other aspects linked to LCT), which may determine the adoption of new technologies such as LCT (Frambach & Schillewaert, 2002).

Moreover, the HDV sector is complex and very heterogeneous (wide variety of applications, fleet sizes, engine configurations, and duty cycles). It has many stakeholders making decisions having different rational choices (Winebrake et al., 2012). Therefore, it is challenging to create a standard or set of mandates and incentives for the sector. Further research in this area is needed to confirm and explore the variation of factors influencing LCT adoption for different fleet sizes (small vs large) and hauling types (short haul vs long haul) in the HDV sector.

Although the existing body of literature on the barriers and opportunities of electrifying on-road vehicles has witnessed noticeable growth, a parallel endeavor in the ORE sector appears to be lacking. In fact, it’s a greater challenge to control emissions in the ORE sector, attributable to a variety of reasons (Hall et al., 2018). Due to the cross-boundary nature of aviation, maritime, and rail as well as the widespread use of off-road construction and agricultural equipment, calculating the precise emission consequences is more challenging. Moreover, (Hall et al., 2018) indicated that government regulation of off-road land vehicles is uneven because of the wide variety of vehicles in the sector, slow vehicle turnover, and operating models that frequently include leases and rentals. Nevertheless, California has been at the forefront of agricultural regulations, which is unique in providing millions of dollars in incentives to encourage growers to prepare for possible mandatory air quality implementation plans (Mccullough et al., 2021).

The major contribution of this study is twofold. The first contribution is contextual as the study fills a key knowledge gap on the association between behavioral factors and LCT adoption in HDV and ORE sectors. The research collects data from semi-structured interviews and analyzes the data using qualitative content analysis. The second contribution is methodological as the study incorporates the assistance of generative artificial intelligence (AI) to refine the analysis and uncover potential contributions/shortcomings of generative AI technologies in qualitative research.

The study makes additional contributions to the literature by exploring the variation of factors influencing LCT adoption among organizations (with respect to their adoption behavior, vocation, and fleet size) and identifying possible discrepancies between available and expected government support for LCT adoption.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The data collection steps are outlined in

Section 2.

Section 3 outlines the methods employed and the results are discussed in

Section 4.

Section 5 presents a summary of the findings, recommendations, and future work.

2. Data

2.1. Indexing and Recruiting

An index of HDV and ORE organizations in California was prepared from the website of Dun & Bradstreet (Dun & Bradstreet, 2022) and cross-referenced with FMCSA Company Snapshot (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2022). Using these resources, 74 HDV (general freight trucking, public transit, and waste collection) and 56 ORE (construction & demolition, farming, and landscaping) organizations were added to the index. To recruit participants in the study, indexed organizations were contacted through five rounds of emailing and phone calls. Representatives from 12 organizations (8 HDV and 4 ORE organizations) consented to participate in the study.

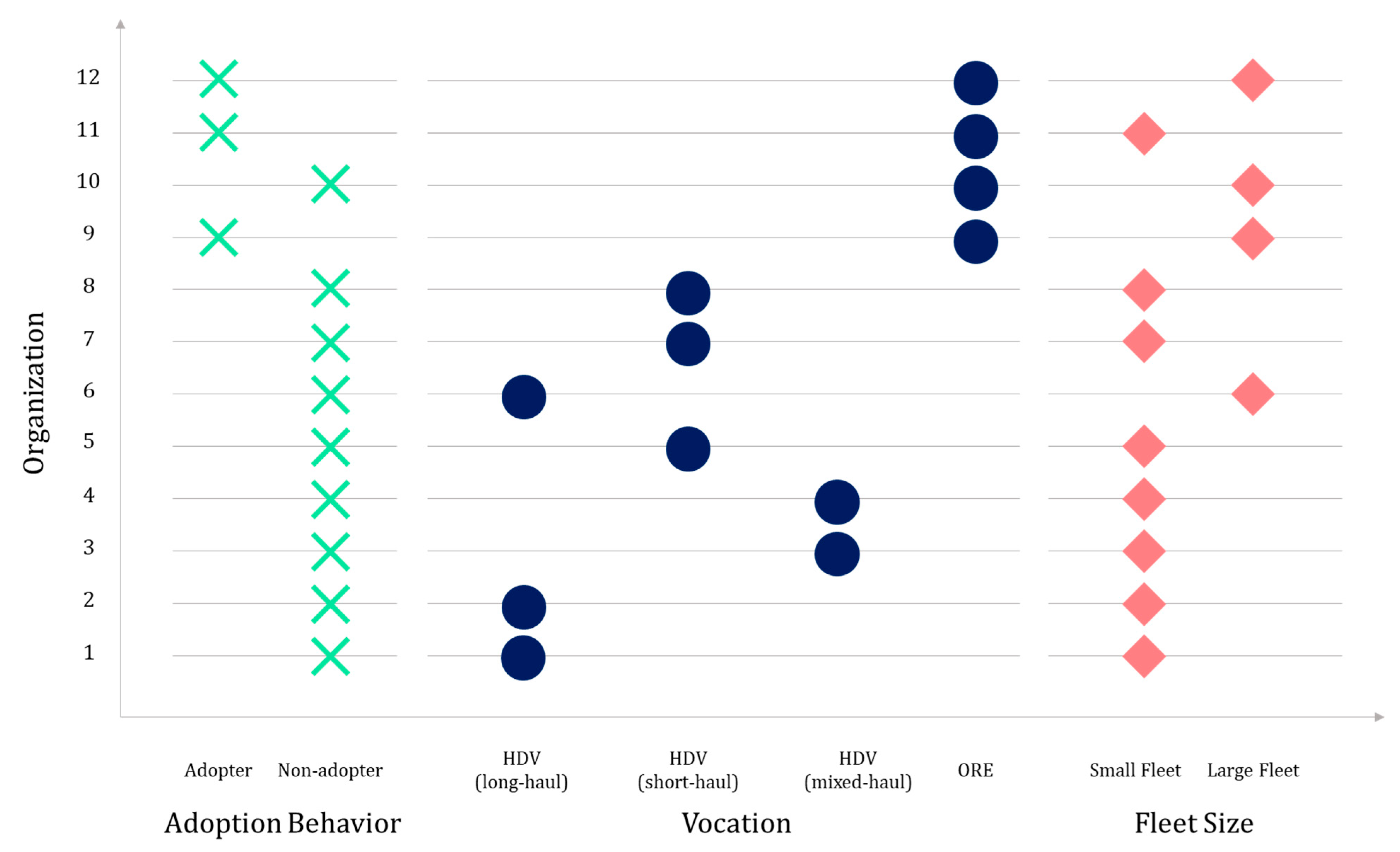

Given the qualitative nature of this study, collecting a statistically representative sample was not the intention. However, a sample size (12 participants) large enough to produce data saturation was collected (Boddy, 2016). Apart from the size of the sample, the participants exhibited as much variability as possible in terms of adoption behavior, vocation, and fleet size (

Figure 1).

2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

The recruited participants took part in semi-structured phone interviews. Engaging in one-on-one dialogue, the semi-structured interviews employed a combination of closed and open-ended questions, often supplemented by follow-up inquiries seeking to delve more into a topic (Adams, 2015). An example of a close-ended questions asked during the interviews is “How many low-carbon vehicles do you have in your fleet?”. And an example of an open-ended question asked to the interviewees is “Are the low-carbon trucks better, or worse than conventional ones? How so?”. Two sets of questions were prepared, one for HDV and another for ORE organizations. Confidentiality of the information, disclosed during interviews, was maintained according to the Institutional Review Board’s guidelines. Participation was voluntary, and participants could skip questions if desired. Due to the semi-structured nature of the interviews, some interviews lasted up to 1 hour long while some lasted 25 minutes.

3. Methodology

Since this study intends to understand the influence of behavioral factors on LCT adoption, a qualitative analysis approach has been employed in the study. A qualitative assessment of the semi-structured interviews would be able to provide a more nuanced understanding of the experiences of the interviewees, compared to quantitative assessments (Carduff et al., 2015). Additionally, since there is a gap in literature with regard to behavioral factors of LCT adoption, a qualitative study would provide preliminary knowledge to inform future quantitative studies and allow them to select relevant features/variables.

3.1. Content Analysis

The interviews were summarized using content analysis. In content analysis, data is analyzed within a context, considering the attributed meaning (Krippendorff, 1989). The analysis was manually conducted by two researchers and then further refined using the assistance of a generative AI tool, as discussed in the following sub-sections.

3.1.1. Manual Coding, Segmentation, and Analysis

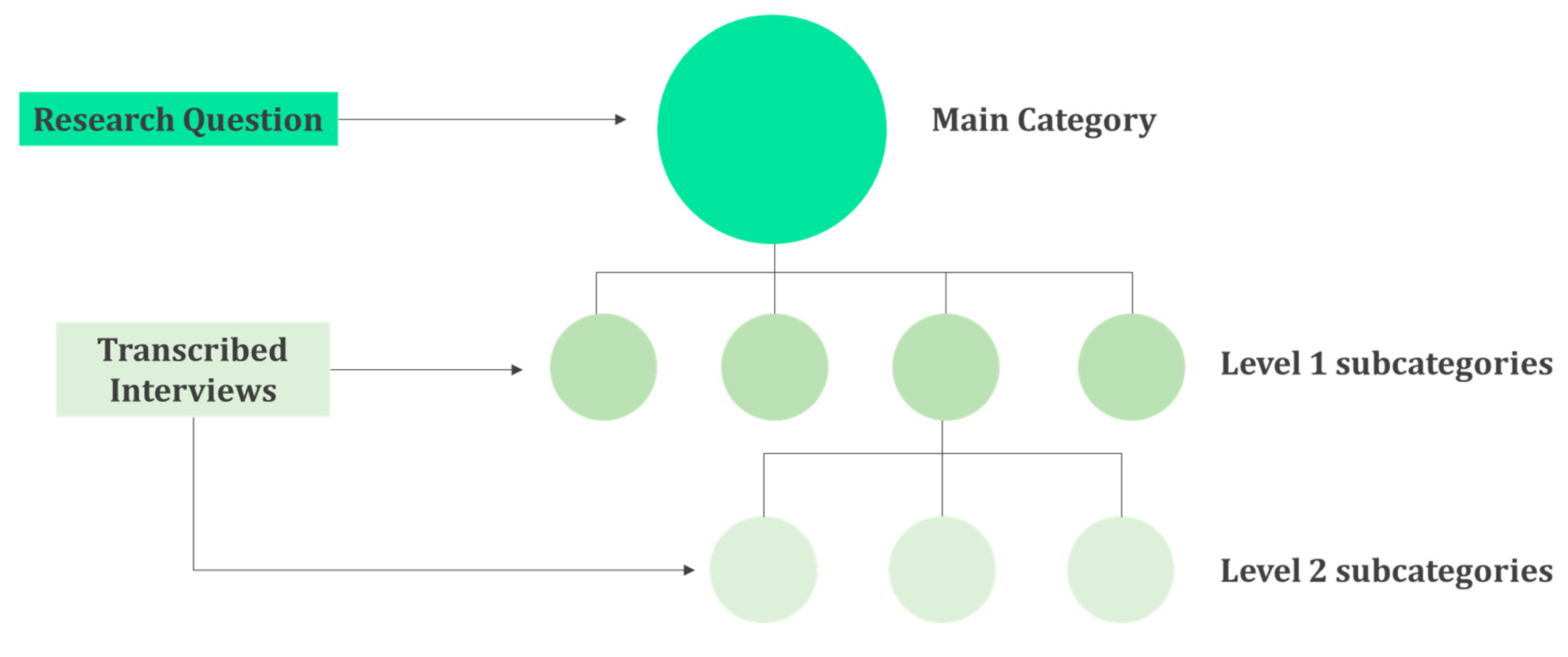

The first step in content analysis involves building a coding framework to structure the material for analysis (Schreier, 2012). Coding frameworks are made up of main categories and subcategories. The main categories are aspects that the researchers are interested in, and the subcategories capture what is said about the aspects of interest (Schreier, 2012). The initial coding framework for this study was built manually using a mix of concept-driven and data-driven strategies (

Figure 2) (Schreier, 2012). The main categories were directly translated from the research questions i.e., they were concept-driven. For example, if one of the research questions was “What are the barriers to LCT adoption in the heavy-duty vehicle sector?”, then a main category named “Barriers to LCT Adoption” was created. The data-driven part of the coding framework comprised of subcategories, generated from the transcribed interviews using the “subsumption” strategy (Schreier, 2012).

Before using the coding framework to structure the material, the interviews were segmented into units of analysis, context units, and coding units (Schreier, 2012) using ATLAS.ti. The interviews themselves were selected as the units of analysis in the study. Since the interviews in the study were semi-structured, the interviewees sometimes made a point using only a word, and sometimes, using several sentences. Hence, changes in topics signaled the end of one coding unit and the beginning of another (Schreier, 2012; Stemler, 2000). The larger body of text around the coding units was selected as context units, which helped in their interpretation (Prasad, 2008).

After segmentation, the manual analysis proceeded to the coding phase, where the coding units were manually assigned to one or more lowest-level sub-categories using ATLAS.ti. A pilot coding phase was conducted to confirm that the framework fulfilled four prerequisite conditions namely, one-dimensionality, mutual exclusiveness, saturation, and exhaustiveness (Schreier, 2012).

In the final steps, statements linked to subcategories were evaluated, considering the importance or sentiments expressed by the interviewees on various topics. Two raters independently assessed the statements, and a data abstraction sheet was used to record importance/sentiment ratings for each subcategory (for every interviewee). Inter-rater agreeability was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa (Cohen, 1960), yielding a score of 0.48 on a scale of 0 to 1. The value indicates that the agreement between the two raters was moderate (Stemler, 2000). Since the interviews were semi-structured, many of the statements didn’t have standardized meanings, the moderate level of agreement was deemed reasonable (Neuendorf et al., 2017). However, all the disagreements were settled through a follow-up discussion and both coders agreed on the final interpretation (Schreier, 2012).

3.1.2. Generative AI assistance

AI has been utilized in qualitative content analysis for studies spanning various disciplines such as psychology (McNamara et al., 2019), marketing (Lee et al., 2020), and healthcare (Lennon et al., 2021). These studies collectively emphasize the efficiency gains enabled by AI in content analysis and demonstrate its ability to support humans in analyzing vast quantities of text featuring natural language. Hence, to further refine the initial coding framework and the results from the manual analysis, the AI coding feature on ATLAS.Ti was used. This feature capitalizes on the latest breakthroughs in generative AI, offered by the introduction of generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) language models (Gillioz et al., 2020). The feature is designed to generate codes and assign the codes to relevant segments of the material being studied. For this study, it was used as an assistive tool instead of a standalone approach. The aim of using the tool in this study was to uncover new insights, potentially overlooked by human coders. Additionally, by using the tool, the study intended to uncover potential contributions and shortcomings of generative AI in qualitative research.

To get the best results out of AI coding, timestamps, and incomplete sentences were removed, grammatical errors were corrected. Unlike manual coding, where the change of topics marked the boundary of coding units, the AI coding feature on ATLAS.Ti could only assign codes to individual paragraphs. Hence, consecutive statements discussing the same topic were kept in one paragraph.

After analyzing the interviews, AI identified 399 codes and assigned them to the paragraphs from the interviewees. Since the AI served as an assistive tool, only the codes capturing novel aspects (overlooked by the initial coding framework) pertaining to the research questions were deemed relevant and worthy of further analysis. Among the 399 codes, 18 were relevant and the remaining 381 were irrelevant. Some of the relevant codes with related meanings were aggregated, reducing the number of relevant codes to 11. All of the relevant codes were added to the initial coding framework as a main category (1 code out of 11) or a sub-category (10 codes out of 11). Some of the names of the sub-categories in the original coding framework were changed to the more representative names provided by AI.

The final coding framework consisted of 13 main categories and one or more levels of subcategories under each main category. The importance/sentiment ratings were assigned for the AI-generated categories, and Cohen’s Kappa was recalculated as discussed in the previous section. The value of Cohen’s Kappa increased slightly (from 0.48 to 0.5) for the final coding framework.

4. Results and Discussion

In the final phase of the content analysis, the ratings for awareness levels were denoted on a scale of 0 to 3 (0=No awareness, 1=low awareness, 2=moderate awareness, 3=high awareness), and the ratings for impression were denoted on a scale of -2 to +2 (-2=highly negative, -1=somewhat negative, 0=neutral, +1=somewhat positive, +2=highly positive) (Murdoch et al., 2019). The importance/emphasis placed on all other subcategories had a scale of 1 to 3 (0=not stated, 1=implied, 2=explicitly stated, 3=emphasized) (Carley, 1993). The results from the content analysis were aggregated and compared based on LCT adoption behavior (3 adopting organizations vs 9 non-adopting organizations), vocation (8 HDV organizations vs 4 ORE organizations), hauling type (3 long-haul organizations vs 3 short-haul organizations vs 2 mixed-haul organizations), and fleet size (8 small fleet organizations vs 4 large fleet organizations) (Table 1 and Table 2). The following sub-sections present the results of the content analysis and their implications.

Table 1.

Awareness, impression, and the three most important factors influencing the LCT adoption behavior of different categories of organizations.

Table 1.

Awareness, impression, and the three most important factors influencing the LCT adoption behavior of different categories of organizations.

| Category of interviewees (Number of interviewees) |

Behavioral factors |

Factors influencing LCT adoption |

| Awareness rating on a scale of 0 to 3 |

Impression rating on a scale of -2 to +2 |

Facilitators (Importance rating on a scale of 0 to 3) |

Barriers (Importance rating on a scale of 0 to 3) |

General Considerations (Importance rating on a scale of 0 to 3) |

| Adopters (3) |

3 |

-1 |

Environmental regulations (1) |

Lack of refueling/recharging facilities (2.67) |

Incentives (1) |

| Less frequent maintenance (1) |

Low operational/load-carrying capacity (2) |

Load carrying capacity (1) |

| Surveillance (1) |

Low range (2) |

Refueling/recharging time (1) |

| Non-adopters (9) |

2.33 |

-1.22 |

Environmental regulations (1.89) |

High purchase cost (1.67) |

Operating cost (2.33) |

| Environmentally friendly (1.44) |

Lack of refueling/recharging facilities (1.67) |

Purchase cost (1.89) |

| Green public relations (0.56) |

Low range (1.22) |

Repair & maintenance cost (1.56) |

| HDV (8) |

2.25 |

-1.38 |

Environmental regulations (2.13) |

High purchase cost (1.88) |

Operating cost (2.5) |

| Environmentally friendly (1.25) |

Lack of refueling/recharging facilities (1.88) |

Purchase cost (2) |

| Green public relations (0.25) |

Low range (1.38) |

Repair & maintenance cost (1.63) |

| ORE (4) |

3 |

-0.75 |

Environmentally friendly (1) |

Lack of refueling/recharging facilities (2) |

Incentives (1) |

| Green public relations (1) |

High refueling/recharging time (1.5) |

Load carrying capacity (0.75) |

| Environmental regulations (0.75) |

Low operational/load-carrying capacity (1.5) |

Operating cost (0.75) |

| Long-haul (3) |

2.33 |

-1.33 |

Environmental regulations (2.67) |

Low range (2.33) |

Operating cost (3) |

| Environmentally friendly (2) |

High purchase cost (2) |

Repair & maintenance cost (2.67) |

| Green public relations (0.67) |

Lack of refueling/recharging facilities (2) |

Purchase cost (2) |

| Short-haul (3) |

1.67 |

-1.33 |

Environmental regulations (3) |

Lack of refueling/recharging facilities (2) |

Purchase cost (2) |

| Environmentally friendly (0.67) |

High purchase cost (1.67) |

Operating cost (1.67) |

| Green public relations (0) |

Low range (1) |

Repair & maintenance cost (1.33) |

| Mixed-haul (2) |

3 |

-1.5 |

Environmentally friendly (1) |

High purchase cost (2) |

Operating cost (3) |

| Environmental regulations (0) |

Expensive batteries (1.5) |

Availability of refueling/recharging facilities (2) |

| Green public relations (0) |

High repair & maintenance cost (1.5) |

Purchase cost (2) |

| Small Fleet (8) |

2.25 |

-1.25 |

Environmental regulations (1.88) |

Lack of refueling/recharging facilities (1.88) |

Operating cost (2.13) |

| Environmentally friendly (0.88) |

High purchase cost (1.5) |

Purchase cost (1.75) |

| Less frequent maintenance (0.38) |

High repair & maintenance cost (1) |

Incentives (1.5) |

| Large Fleet (4) |

3 |

-1 |

Environmentally friendly (1.75) |

Low range (2.5) |

Operating cost (1.5) |

| Green public relations (1.5) |

High refueling/recharging time (2) |

Purchase cost (1.25) |

| Environmental regulations (1.25) |

Lack of refueling/recharging facilities (2) |

Repair & maintenance cost (1.25) |

Table 2.

Awareness, impression, and the three most important reasons negatively influencing the impression of incentives and expected government support for different categories of organizations.

Table 2.

Awareness, impression, and the three most important reasons negatively influencing the impression of incentives and expected government support for different categories of organizations.

| Category of interviewees (Number of interviewees) |

Behavioral factors |

Reason behind negative impression (Importance rating on a scale of 0 to 3) |

Expected government support (Importance rating on a scale of 0 to 3) |

| Awareness rating on a scale of 0 to 3 |

Impression rating on a scale of -2 to +2 |

| Adopters (3) |

2.67 |

0.33 |

Difficult to acquire (1.67) |

Less restrictive environmental regulations (1) |

| Conditions/restrictions (1) |

Charging infrastructure support (0.67) |

| Cost ineffective (1) |

Collaboration with manufacturers (0.67) |

| Non-adopters (9) |

2 |

0 |

Distrust of Government (0.67) |

Charging infrastructure support (2.11) |

| Conditions/restrictions (0.56) |

More monetary incentives (1.22) |

| Cost ineffective (0.33) |

Indirect/concealed government involvement (0.56) |

| HDV (8) |

2.13 |

0.13 |

Distrust of Government (0.75) |

Charging infrastructure support (2) |

| Conditions/restrictions (0.63) |

More monetary incentives (1.38) |

| Cost ineffective (0.38) |

Indirect/concealed government involvement (0.63) |

| ORE (4) |

2.25 |

0 |

Difficult to acquire (1.25) |

Less restrictive environmental regulations (1.5) |

| Conditions/restrictions (0.75) |

Charging infrastructure support (1.25) |

| Cost ineffective (0.75) |

Collaboration with manufacturers (0.5) |

| Long-haul (3) |

2.33 |

0.67 |

Conditions/restrictions (1) |

Charging infrastructure support (2.67) |

| Difficult to acquire (0.67) |

More monetary incentives (1) |

| - |

Educational/marketing campaigns for the new technology (0.33) |

| Short-haul (3) |

1.67 |

0.33 |

Waiting period (1) |

More monetary incentives (2.67) |

| Distrust of Government (1) |

Charging infrastructure support (1.67) |

| - |

Indirect/concealed government involvement (0.67) |

| Mixed-haul (2) |

2.5 |

-1 |

Cost ineffective (1) |

Charging infrastructure support (1.5) |

| Bureaucracy (1) |

Collaboration with manufacturers (1.5) |

| - |

Indirect/concealed government involvement (1.5) |

| Small Fleet (8) |

2.13 |

0.13 |

Distrust of Government (0.75) |

Charging infrastructure support (1.88) |

| Conditions/restrictions (0.63) |

More monetary incentives (1.38) |

| Cost ineffective (0.38) |

Indirect/concealed government involvement (0.63) |

| Large Fleet (4) |

2.25 |

0 |

Waiting period (1.25) |

Charging infrastructure support (1.5) |

| Conditions/restrictions (0.75) |

Less restrictive environmental regulations (1.5) |

| Cost ineffective (0.75) |

Collaboration with manufacturers (0.5) |

4.1. Behavioral Factors of LCT Adoption

As previously discussed, behavioral factors (awareness and impression) may play an important role in the adoption of new technologies such as LCT. The following sub-sections discuss the association of these behavioral factors with LCT adoption and how the factors vary with respect to adoption behavior, vocation, and fleet size.

4.1.1. Awareness and Impression of LCT

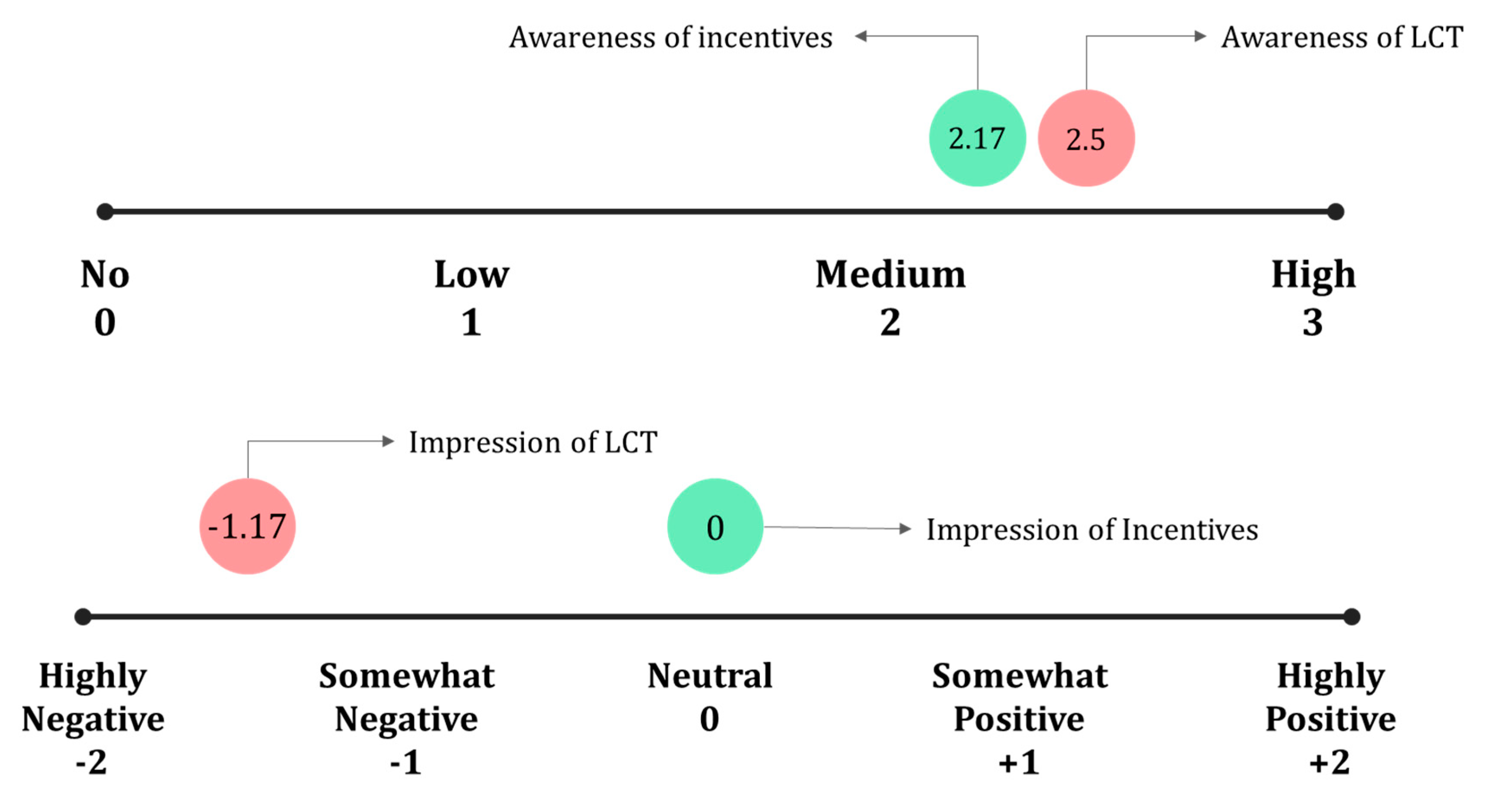

On a scale of 0 to 3, the average awareness of LCT among the interviewed organizations was 2.5 (

Figure 3). However, subtle differences in awareness levels were observed among different groups of organizations with respect to adoption behavior, vocation, and fleet size (Table 1). Compared to large ORE companies and large mixed-haul HDV firms, smaller long-haul and short-haul trucking companies in the HDV sector showed a lower level of LCT awareness.

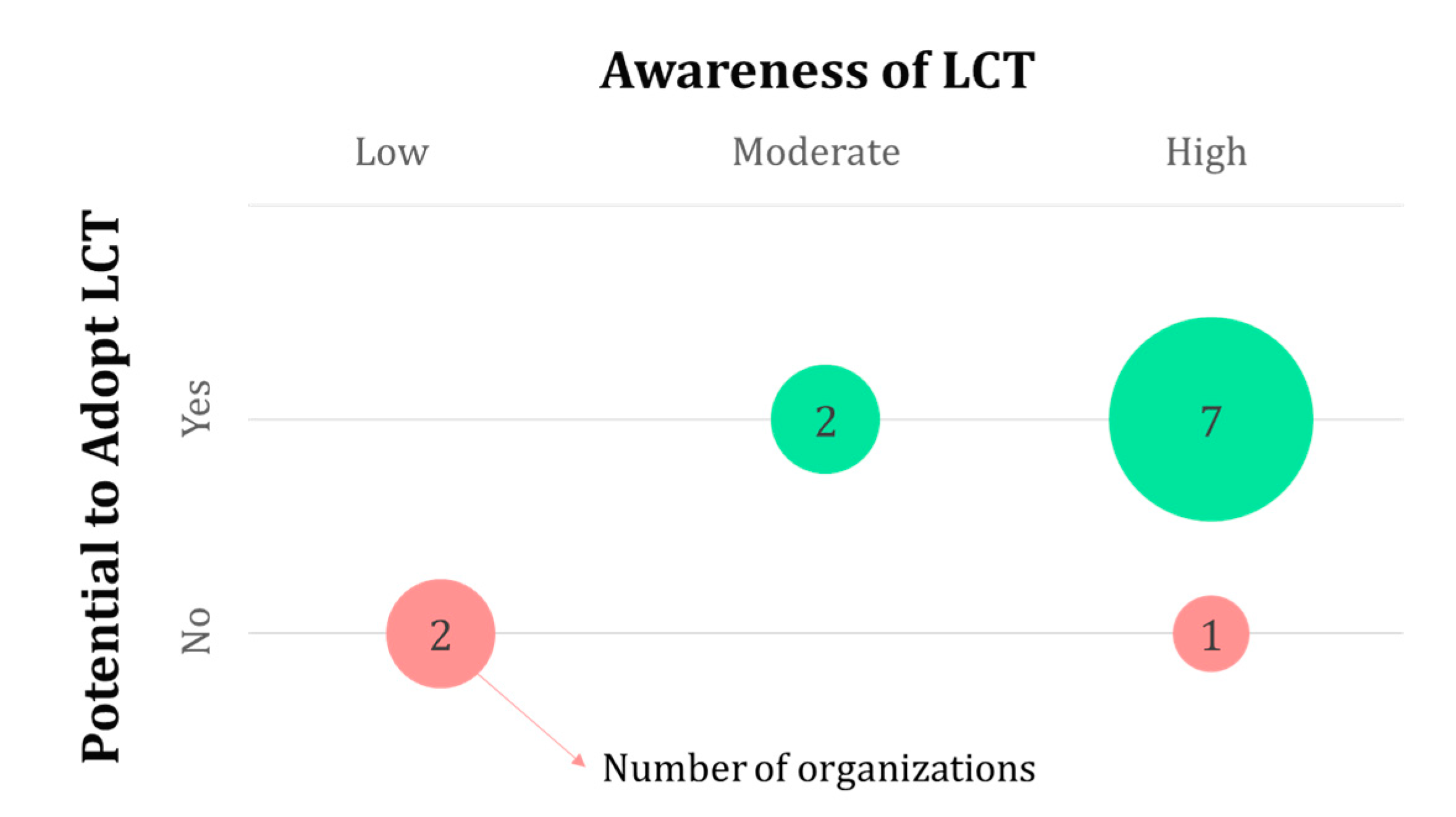

On average the adopters demonstrated a higher awareness of LCT compared to the non-adopters. Non-adopters also included organizations having diesel fleets equipped with emission reduction technologies. In the technology adoption process for organizations, awareness is recognized as the initial stage (Frambach & Schillewaert, 2002). Consequently, a higher level of awareness of LCT among current adopters is expected. Apart from assessing the role of awareness in current LCT adoption, its role in future LCT adoption was also assessed. It was found that interviewees who demonstrated a higher awareness of LCT were more likely to represent organizations planning to adopt LCT or expand their LCT fleet (

Figure 4). These findings highlight a positive association between awareness of LCT and LCT adoption.

When the behavioral factors were compared among different vocations and fleet sizes of organizations, the positive association between awareness of LCT and its adoption held true; subgroups of organizations with higher awareness had a larger share of adopters. The ORE organizations had a higher awareness of LCT compared to the HDV organizations. At the same time, 3 out of 4 ORE organizations were adopters (compared to 0 adopters among the HDV organizations) (

Figure 1). Similarly, small-fleet organizations, who had a lower share of adopters (1 adopter out of 8 small-fleet organizations compared to 2 adopters out of 4 among large-fleet organizations), were found to possess a lower awareness level compared to large-fleet organizations. These smaller organizations are usually aware of LCTs but lack comprehensive knowledge on factors like financing and technology (Wong, 2022).

Although none of the HDV organizations adopted LCT, the mixed-haul organizations had a higher awareness of LCT compared to the other HDV organizations (short-haul and long-haul). The diverse vocations and vehicle range (Hughes, 1973) prevalent within mixed-haul organizations might make them more aware of available technologies such as LCT.

Although a positive association between awareness of LCT and its adoption was noticed, the same cannot be said about the impression of LCT. Adopters and non-adopters alike had negative impressions of LCT. The dissatisfaction with LCT among adopters might be explained by the technical limitations of LCT (discussed in the next sub-section). The negative impression may also be attributed to the intrinsic beliefs, business values, and strategic motives of the organizations (Bae et al., 2022). The overall impression of LCT among the organizations was somewhat negative to highly negative, with a rating of -1.17 (

Figure 3). Among all the groups of organizations, the mixed-haul HDV organizations had the most unfavorable impression of LCT (Table 1).

4.1.2. Awareness and Impression of Incentives

On a scale of 0 to 3, the overall awareness of the organizations was 2.17 (

Figure 3). This was lower than the awareness of LCT. On a scale of -2 (highly negative) to +2 (highly positive), the overall impression of incentives that they had on incentives was 0.08, in contrast to their somewhat negative (-1.17) impression of LCT (

Figure 3).

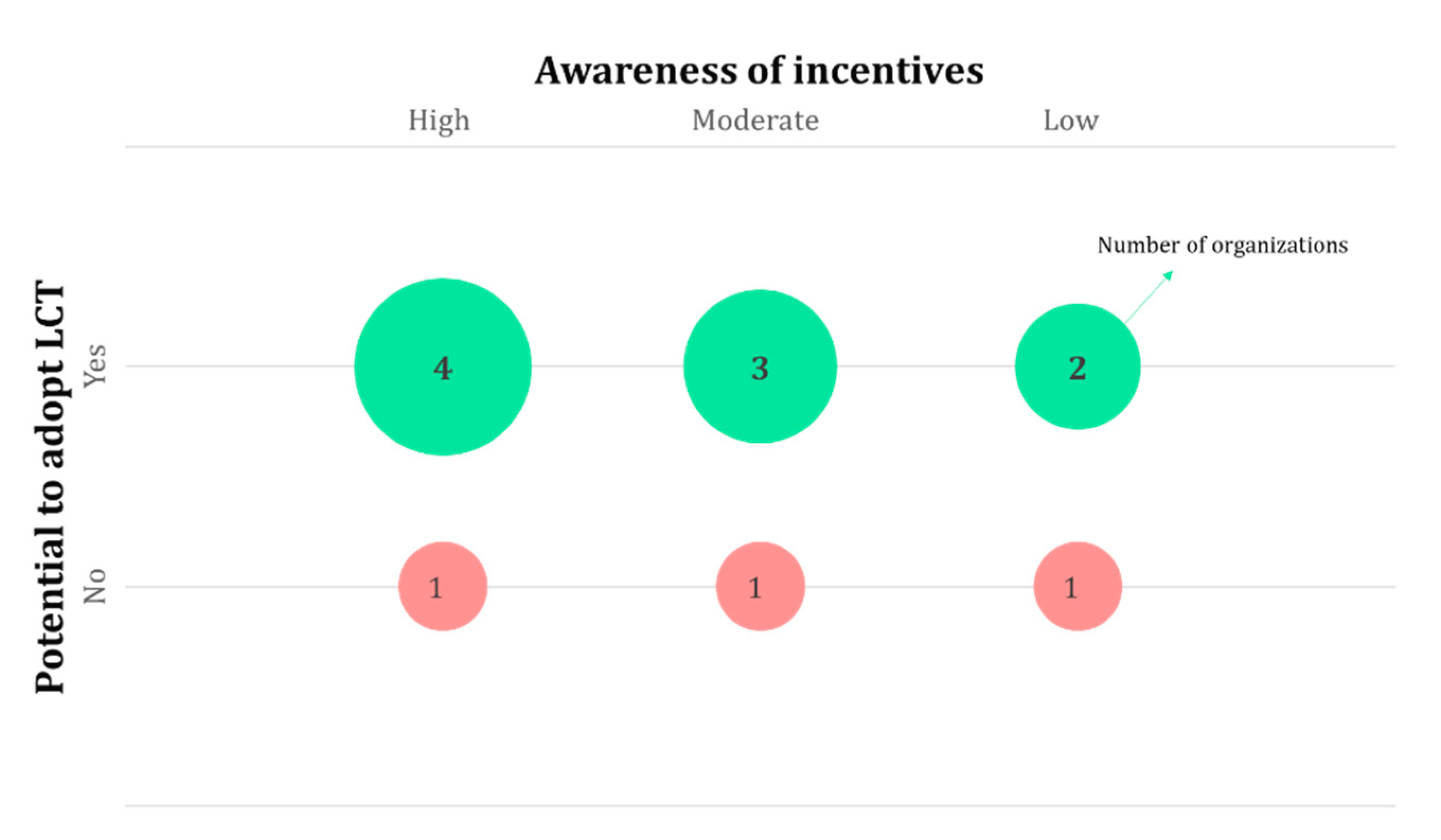

Similar to the findings on awareness and impression of LCT, the awareness of incentives was higher among adopters compared to non-adopters (Table 2). The adopters also had the better impression of incentives. In addition,

Figure 5 shows that interviewees who demonstrated a higher awareness of incentive programs were more likely to represent organizations planning to adopt LCT or expand their LCT fleet. These findings suggest that the awareness of incentives is also positively associated with LCT adoption. The positive association necessitates information dissemination of available incentive programs (Wong, 2022) to foster LCT adoption.

The assessment of awareness of incentives for different adoption behaviors, vocations, and fleet sizes (Table 2) further underscores the positive association between awareness of incentives and LCT adoption. The overall awareness of incentives among ORE organizations, who were mostly adopters (3 out of 4), was higher than that of the HDV organizations, who were all non-adopters. Similarly, the large-fleet organizations, who had a higher share of adopters, were more aware of incentives than the small-fleet organizations. While it is important to raise awareness levels among these small-fleet organizations, it is also important to acknowledge that government agencies find it more difficult to reach out to them (Brito, 2022). Although none of the HDV organizations adopted LCT, the mixed-haul HDV organizations demonstrated the highest awareness of incentives compared to the other HDV organizations (short-haul and long-haul).

Although seven out of nine potential adopters of LCT had a high or moderate awareness of incentives, two interviewees with low awareness of incentives also stated their intention to adopt LCT (

Figure 5). One of these organizations stated that they intend to adopt LCT only because they are mandated (by environmental regulations) to do so. The other organization mentioned fuel efficiency and environmental friendliness of LCT as contributing factors to their intention to adopt. It is important to further explore why organizations intend to adopt LCT despite their lack of awareness about LCT incentives. Such explorations can achieve saturation of information by including a larger sample of interviewees from this subgroup.

The analysis of impression revealed subtle differences with respect to adoption behavior, vocation, and fleet size of organizations (Table 2). More importantly, it was found that lower awareness of incentives doesn’t necessarily lead to a more negative impression. For instance, the small-fleet organizations had a lower level of awareness of incentives (compared to the large-fleet organizations), but their impression was better, suggesting that they perceived incentives as more valuable.

4.1.3. Environmental Awareness

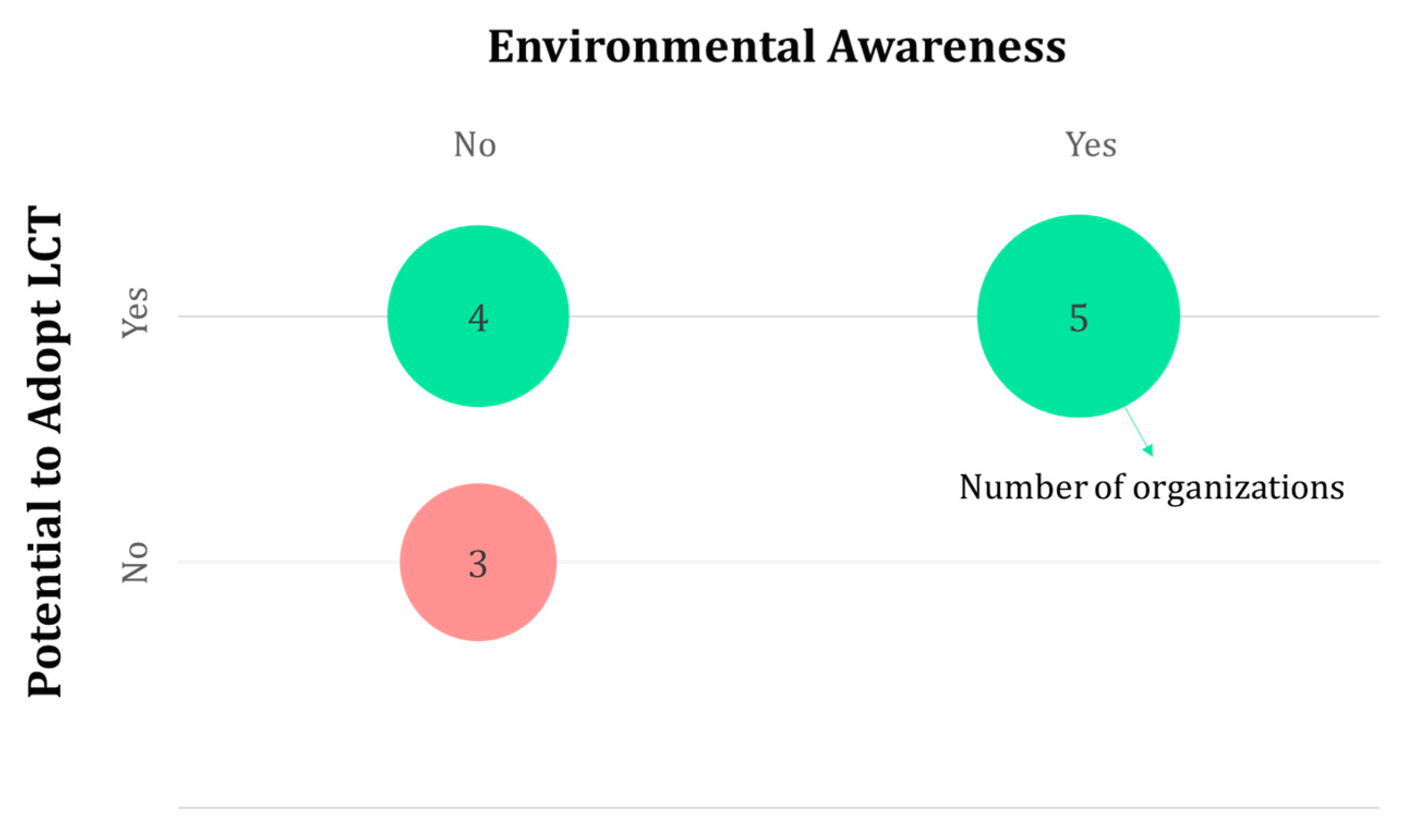

A positive association between environmental awareness and potential to adopt LCT was also observed from the analysis. The five interviewees, who demonstrated some level of environmental concern/awareness during the interviews, represented organizations that are planning to adopt LCT (

Figure 6). This suggests that there exists a positive association between general environmental awareness and the intention to adopt LCT in the HDV and ORE sectors. Similar associations have been confirmed in the light-duty sector by several studies (Kowalska-Pyzalska, 2018).

Four organizations didn’t demonstrate general environmental awareness but intended to adopt LCT (

Figure 6). Three out of these four organizations mentioned that they intended to adopt LCT because of environmental regulations. One of these four organizations mentioned the low cost and frequency of maintenance as factors motivating them to adopt LCT. Future studies can narrow down their focus on this sub-group of organizations and explore them further.

4.2. Other Factors influencing LCT adoption

Although behavioral factors are important determinants of LCT adoption, they aren’t the sole determinants. This section discusses the other factors influencing LCT adoption (facilitators, barriers, general consideration), and their varying importance for different adoption behaviors, vocations, and fleet sizes.

4.2.1. Facilitators

The three most important facilitators of LCT adoption were environmental regulations (1.67 on a scale of 0 to 3), environmental friendliness of the vehicles (1.17 on a scale of 0 to 3), and green public relations (0.5 on a scale of 0 to 3). Although environmental regulations were the most important facilitator, they didn’t always lead to AFV adoption. Instead of adopting AFVs, many interviewed organizations complied with environmental regulations by adding DEF filters to diesel vehicles.

>Table 1 presents the most important facilitators for different groups of organizations. The contrast between the facilitators for HDV and ORE organizations offers valuable insight. Environmental regulations stood out as the pivotal facilitator for LCT adoption among HDV organizations, while ORE organizations emphasized environmental friendliness and green public relations as their top facilitators. Past research has verified the tendency of organizations to expand their low-carbon fleet as a strategic move to enhance public image (Sierzchula, 2014). In this regard, one of the ORE interviewees mentioned, “Well, we’re located right near Silicon Valley in California. So, a lot of high-tech companies use biodiesel or low-CARB emission-type equipment. We try to cater to them a little bit.”

Interestingly, infrequent maintenance, a facilitator acknowledged in prior research (Bae et al., 2022), was among the most important ones for small organizations and adopting organizations. An interviewee from a small fleet organization stated, “They’re relatively maintenance-free, so I don’t have to worry about checking the oil on them every time I start it up, I don’t have to worry about air filters clogging up”.

4.2.2. Barriers

When the barriers were individually ranked, lack of refueling/recharging facilities (1.92 on a scale of 0 to 3), high purchase cost (1.5 on a scale of 0 to 3) and low range (1.42 on a scale of 0 to 3) were found to be the three most important ones. Table 1 presents the biggest barriers for different groups of organizations.

Significant insights can be drawn from the biggest barriers faced by adopters and non-adopters as well as those faced by small-fleet and large-fleet organizations. The most important barriers for adopting organizations and large-fleet organizations were from the technical category, suggesting that technical barriers may hinder their LCT fleet expansion, even after they have overcome the financial barriers to adopt them. However, these financial barriers were among the biggest barriers for small-fleet organizations and non-adopters. Hence, incentives aimed at mitigating financial barriers are particularly vital for smaller non-adopting organizations. These incentives may foster adoption among small-fleet organizations as these organizations are argued to be innovative, flexible, and more receptive toward new technologies (Frambach & Schillewaert, 2002).

One of the less common but important barriers that came up during the interviews was resistance to change. As one of the interviewees mentioned, “The reason we wouldn’t change is because it’s a total change in our operation and that would be expensive”. The theory of psychological inertia (a tendency to repeat specific behaviors) (Gao et al., 2020) may explain this resistance to change. The government could consider introducing accessible vehicle leasing schemes for non-adopters to experiment with new LCT models and possibly reduce their psychological inertia. Additionally, to make the change in operations smoother for these organizations, the regulators might want to consider a phased transition towards LCT rather than implementing an “all-at-once” policy (Alp et al., 2019). Another less common but important barrier was the inability of LCT to fulfill extreme requirements. This might be a legitimate barrier because the already limited range of LCT (specifically electric vehicles) is further reduced by extreme conditions like heavy loads and high temperatures (Quak et al., 2016).

4.2.3. General Considerations

Apart from facilitators and barriers to LCT adoption, the interviews featured some general considerations that organizations make when purchasing any vehicle (Table 1). Among the different considerations, operating cost (1.92 on a scale of 0 to 3), purchase cost (1.58 on a scale of 0 to 3), and presence of incentives (1.33 on a scale of 0 to 3) were among the most important considerations.

The general considerations for adopters and non-adopters align with the findings from the barriers section; LCT-adopting organizations were more concerned about technical considerations while the non-adopting organizations were more concerned about the financial considerations. Operating cost was the most important consideration for long-haul and mixed-haul organizations, attributable to their heavier load and higher energy requirements (Mareev et al., 2018). For short-haul organizations, the most important consideration was the purchase cost. For small organizations, incentives were among the top three considerations for vehicle purchase, unlike the large organizations.

4.3. Existing Incentives and Expected Government Support

Although monetary incentives were stated as important considerations for vehicle purchase, the interviewees mentioned six different factors that negatively influence the impression of incentives. These factors unveil discrepancies between the expectations of the organizations and the current state of government support for LCT adoption. Hence, these factors need to be addressed to realize the potential of incentives as facilitators of LCT adoption. The factors can be ranked in the following order: conditions/restrictions (0.67 on a scale of 0 to 3), difficulty to acquire (0.58), cost ineffectiveness (0.50), distrust of government (0.50), bureaucracy (0.25), and waiting period (0.25).

Conditions/restrictions frequently came up as an important factor (especially among small and long-haul organizations), determining the impression of incentives. One interviewee stated that applying for incentives would mean that a huge chunk of his operations would be restricted within California only and it would be detrimental to his/her business. To make incentives more lucrative for organizations, it is imperative to remove burdensome restrictions and streamline the application process to the extent possible (Wong, 2022). Another important factor that came up during the interviews was distrust of the government. When talking about the lack of trust the industry has in the government, one of the interviewees stated, “Any government involvement, the more it’s under the radar, I think the more effective it’s going to be, knowing the industry like I do”. Hence, even though regulatory/punitive environmental mandates cause diffusion of LCTs, they may make organizations less receptive to rewarding interventions (e.g., incentives) coming from the government. Therefore, it is recommended that policymakers recognize this tradeoff and use punitive interventions sparingly (Shi et al., 2021).

When asked about expected forms of government support, the organizations mentioned charging infrastructure support (1.75 on a scale of 0 to 3), monetary incentives (0.92 on a scale of 0 to 3), and collaboration with manufacturers (0.5 on a scale of 0 to 3) as the three most important ones. Since the lack of charging/refueling infrastructure came up as the most important barrier, it is expected that the organizations would be seeking charging infrastructure support. However, some interviewees also suggested potential technological improvements such as swappable batteries (Quak et al., 2016) and solar chargers, where the government can allocate resources. The government may also consider supporting manufacturers to come up with range extender technologies (Jahangir Samet et al., 2021) to mitigate the challenges of limited range. A statement from one of the interviewees emphasizes the need for technological improvements (Bae et al., 2022) and suggests that financial incentives are not enough to ensure long-term diffusion of LCT. He/she mentioned, “The incentives don’t make up for the short-range on the electric vehicles. You know the incentives don’t overcome the problems they just offer you a little cash to deal with the problems indefinitely”.

Given the heterogeneous landscape of the HDV and ORE sectors, the factors influencing the impression of incentives and expected government support differed for different groups of organizations (Table 2). Hence, targeted incentive programs tailored to the varying expectations of organizations may prove to be an effective approach (Wong, 2022).

4.4. Generative AI in Content Analysis

Although the AI coding tool on ATLAS.Ti is still at its preliminary stage of development, using it as an assistive tool revealed ways in which generative AI can positively contribute to qualitative research.

Firstly, the codes produced by a generative AI tool can provide a summary of the studied material and the human coders could use the codes to validate the original framework or identify new concepts overlooked by the framework. In this study only 18 (4.5%) out of the 399 AI codes were found to capture new concepts, which weren’t already identified by the original coding framework. Hence, it was an indication that the original framework captured most of the concepts relevant to the research questions. However, the AI tool offered a new perspective, and the original framework was refined using the 18 codes that captured new concepts. For instance, the subcategories “resistance to change” and “inability to fulfill extreme requirements” produced by the AI tool were newly added under the pre-existing main category “barriers to LCT adoption”. The AI tool also produced a main category named “environmental awareness” which was found to have a positive association with the potential to adopt LCT.

Secondly, a generative AI tool can identify new statements that belong to existing categories of the original coding framework. For instance, the sentence “Well, we would like to see some history of fleets that have changed over and what they ran into, to decide on how soon we’d want to change” was assigned the code “unproven technology” by the AI tool. Although “unproven technology” was a pre-existing subcategory (under “barriers to LCT adoption”), the human coders did not assign a category to the aforementioned statement during the manual coding phase. However, upon reevaluation of the statement, the code “unproven technology” was found to be a suitable subcategory for the statement.

Thirdly, generative AI can be used as a suggestive tool to find more suitable names for categories in the original coding framework. For instance, the subcategory “paperwork” (under the main category “reasons behind negative impression of incentives”) was more aptly changed to “bureaucracy” as it provided a more general description of the content being analyzed (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008).

Apart from the positive contributions of generative AI in this study, some potential areas of improvement were also discovered. Firstly, a generative AI tool needs to be fine-tuned to gather numerous statements sharing the same meaning under one code. Unless the tool can accomplish this task, the purpose (saving time) of using AI in a qualitative study would be defeated. This was especially prevalent in this study as 296 (74.2%) out of 399 codes generated had only one statement associated with them. This is an issue because coding is meant to reduce the data instead of proliferating it (Bernard, 2000). Hence, even though the generation and assignment of codes using an AI tool takes very little time, aggregating codes to summarize the data may consume a considerable amount of time depending on the number of codes generated. Secondly, a generative AI tool needs to detect the nuances in natural language almost in the same way a human being can. Unless the AI tool can detect such nuances, it may assign wrong codes to statements. For instance, the AI tool inappropriately assigned the code “environmental concern” to the statement “We were motivated to acquire low-carbon vehicles because California was imposing some restrictions”. Although the organization did purchase low-carbon vehicles, they did so because of legal restrictions not because of environmental concern.

5. Conclusions

This study employed generative-AI-assisted content analysis to understand the association of behavioral factors with LCT adoption and explore the variation in factors influencing LCT adoption among different groups of organizations (with respect to adoption behaviors, vocations, and fleet sizes). Moreover, the study also identified some discrepancies between expected and available government support for LCT adoption.

With regard to the behavioral factors, a positive association was found between potential to adopt LCT and awareness of LCT. A positive association was also noticed between the potential to adopt LCT and awareness of different aspects (incentives and the environment) linked to LCT. This underscores the importance of raising awareness levels within organizations regarding factors linked to LCT. To this end, the government could consider introducing accessible vehicle leasing schemes for non-adopters to experiment with new low-carbon technologies. Moreover, they should invest more in educational/outreach programs to increase the awareness of available incentive programs. The smaller long-haul and short-haul trucking companies operating in the HDV sector were found to have a lower level of awareness of LCT (compared to the ORE companies and larger mixed-haul HDV companies). Therefore, these organizations may be prioritized when planning initiatives designed to increase organizational awareness of LCT. However, further research is needed to confirm this.

The factors (including behavioral factors) influencing LCT adoption varied with respect to different adoption behaviors and vocations, suggesting a need for tailored incentives to facilitate LCT adoption among different groups of organizations. Environmental mandates were the most important reason behind LCT adoption in the HDV organizations, while the ORE organizations were mostly driven by environmental concern and opportunities to form green public relations. The financial barriers received greater importance among the non-adopters and smaller organizations compared to the larger organizations. On the other hand, for adopters and larger organizations, technical barriers received paramount importance.

The analysis of statements on available incentives identified a range of issues (e.g., conditions/restrictions, difficulty to acquire) with existing incentive programs that may limit their effectiveness as facilitators of LCT adoption. Hence, in order to ensure that government support initiatives facilitate LCT adoption, these issues should be addressed. Moreover, the analysis results suggest that the government should extend further support to charging infrastructure and technological improvements.

By using generative AI as an assistive tool, some additional insights were uncovered from the data, which the human coders overlooked in their analysis. This suggests the potential of this emerging technology to validate and refine the coding framework used in content analysis. However, to achieve better results, the ability of generative AI tools to produce aggregate-level codes and identify the nuances of natural language needs to be ensured.

The organizations, which were interviewed for this study, exhibited as much variability as possible in terms of adoption behavior, vocation, and fleet size. However, there are other organizational differences that were not captured in the sample. Hence, future research can explore heterogeneity in LCT adoption behavior based on other such differences (e.g., operations, energy demands, duty cycles) among HDV and ORE organizations. These future studies can leverage the power of generative AI, finding more creative ideas for its application as technology evolves.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm the following contributions to the article: Study conception and design: Suman Mitra, Vuban Chowdhury, Farzana Mehzabin Tuli; Data Collection and Sampling: Vincent Rubinelli, Vuban Chowdhury, Farzana Mehzabin Tuli, Suman Mitra; Content Analysis: Vuban Chowdhury, Farzana Mehzabin Tuli; Result interpretation: Vuban Chowdhury, Farzana Mehzabin Tuli; Draft manuscript preparation: Vuban Chowdhury, Farzana Mehzabin Tuli, Suman Mitra; Supervision: Suman Mitra. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper is partly supported by the California Air Resources Board. The contents of this paper reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. This paper does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation.

Competing Interests

The authors report that they have no financial or non–financial competing interests.

References

- Adams, W. C. (2015). Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation: Fourth Edition (pp. 492–505). Wiley Blackwell. [CrossRef]

- Alp, O., Tan, T., & Udenio, M. (2019). Adoption of Electric Trucks in Freight Transportation.

- Anderhofstadt, B., & Spinler, S. (2019). Factors affecting the purchasing decision and operation of alternative fuel-powered heavy-duty trucks in Germany – A Delphi study. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 73, 87–107. [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y., Mitra, S. K., Rindt, C. R., & Ritchie, S. G. (2022). Factors influencing alternative fuel adoption decisions in heavy-duty vehicle fleets. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 102. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H. R. (2000). Social Research Methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (1st ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research, 19(4), 426–432. [CrossRef]

- Brito, J. (2022). No fleet left behind: Barriers and opportunities for small fleet zero-emission trucking. www.theicct.org.

- Burke, A., & Miller, M. (2020). Zero-Emission Medium-and Heavy-duty Truck Technology, Markets, and Policy Assessments for California. [CrossRef]

- California Air Resources Board. (2023). Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Project.

- Cao, Y., Li, S., Lv, C., Wang, D., Sun, H., Jiang, J., Meng, F., Xu, L., & Cheng, X. (2023). Towards cyber security for low-carbon transportation: Overview, challenges and future directions. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 183, 113401. [CrossRef]

- Carduff, E., Murray, S. A., & Kendall, M. (2015). Methodological developments in qualitative longitudinal research: The advantages and challenges of regular telephone contact with participants in a qualitative longitudinal interview study. BMC Research Notes, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Carley, K. (1993). Coding choices for textual analysis: A comparison of content analysis and map analysis. Sociological Methodology, 23, 75–126. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1960). A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Dun & Bradstreet. (2022). Dun & Bradstreet. https://www.dnb.com/.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Frambach, R. T., & Schillewaert, N. (2002). Organizational innovation adoption A multi-level framework of determinants and opportunities for future research. Journal of Business Research, 5, 163–176. [CrossRef]

- Gao, K., Yang, Y., Sun, L., & Qu, X. (2020). Revealing psychological inertia in mode shift behavior and its quantitative influences on commuting trips. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 71, 272–287. [CrossRef]

- Gillioz, A., Casas, J., Mugellini, E., & Khaled, O. A. (2020). Overview of the Transformer-based Models for NLP Tasks. Proceedings of the 2020 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, FedCSIS 2020, 179–183. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J., Lecroy, C., Latif, B., Ichien, D., Arora, M., Johnson, K., Kailas, A., Fenton, D., & Brandis, K. (2022). The Zero-Emission Freight Revolution: California Case Studies. 35thInternational Electric Vehicle Symposium and Exhibition (EVS35).

- Hall, D., Pavlenko, N., & Lutsey, N. (2018). Beyond road vehicles: Survey of zero-emission technology options across the transport sector.

- Huang, Z., & Fan, H. (2022). Responsibility-sharing subsidy policy for reducing diesel emissions from in-use off-road construction equipment. Applied Energy, 320, 119301. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R. K. (1973). A Stochastic Approach for the Economic Analysis of Asphaltic Concrete Production.

- Jahangir Samet, M., Liimatainen, H., van Vliet, O. P. R., & Pöllänen, M. (2021). Road freight transport electrification potential by using battery electric trucks in Finland and Switzerland. Energies, 14(4), 823. 4. [CrossRef]

- Jin, L., Searle, S., & Lutsey, N. (2014). Evaluation of State-Level U.S. Electric Vehicle Incentives.

- Kowalska-Pyzalska, A. (2018). What makes consumers adopt to innovative energy services in the energy market? A review of incentives and barriers. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (Vol. 82, pp. 3570–3581). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (1989). Content Analysis. International Encyclopedia of Communication, 1, 403–407. http://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/226.

- Lee, L. W., Dabirian, A., McCarthy, I. P., & Kietzmann, J. (2020). Making sense of text: artificial intelligence-enabled content analysis. European Journal of Marketing, 54(3), 615–644. [CrossRef]

- Lennon, R. P., Fraleigh, R., van Scoy, L. J., Keshaviah, A., Hu, X. C., Snyder, B. L., Miller, E. L., Calo, W. A., Zgierska, A. E., & Griffin, C. (2021). Developing and testing an automated qualitative assistant (AQUA) to support qualitative analysis. Family Medicine and Community Health, 9. [CrossRef]

- Mareev, I., Becker, J., & Sauer, D. U. (2018). Battery dimensioning and life cycle costs analysis for a heavy-duty truck considering the requirements of long-haul transportation. Energies, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Mccullough, M., Hamilton, L., & Walters, C. (2021, August). Cost Effectiveness of California’s Clean Air Act Agricultural Equipment Incentives. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu.

- McNamara, P., Duffy-Deno, K., Marsh, T., & Marsh Jr, T. (2019). Dream content analysis using Artificial Intelligence. International Journal of Dream Research, 12(1). www.ai-one.com.

- Murdoch, B., Marcon, A. R., Downie, D., & Caulfield, T. (2019). Media portrayal of illness-related medical crowdfunding: A content analysis of newspaper articles in the United States and Canada. PLoS ONE, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K. A., Skalski, P. D., Cajigas, J. A., & Allen, J. C. (2017). The content analysis guidebook (Vol. 2).

- Perez, P., Menares, C., & Ramírez, C. (2020). PM2.5 forecasting in Coyhaique, the most polluted city in the Americas. Urban Climate, 32. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B. D. (2008). Content Analysis: A method in Social Science Research. In Research methods for social work. [CrossRef]

- Quak, H., Nesterova, N., & Van Rooijen, T. (2016). Possibilities and Barriers for Using Electric-powered Vehicles in City Logistics Practice. Transportation Research Procedia, 12, 157–169. [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Sage. www.sagepub.co.uk/schreier.

- Seitz, C. S., Beuttenmüller, O., & Terzidis, O. (2015). Organizational adoption behavior of CO2-saving power train technologies: An empirical study on the German heavy-duty vehicles market. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 80, 247–262. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Wei, Z., Shahbaz, M., & Zeng, Y. (2021). Exploring the dynamics of low-carbon technology diffusion among enterprises: An evolutionary game model on a two-level heterogeneous social network. Energy Economics, 101. [CrossRef]

- Sierzchula, W. (2014). Factors influencing fleet manager adoption of electric vehicles. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 31, 126–134. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., & Purohit, B. M. (2014). Public Health Impacts of Global Warming and Climate Change. Peace Review, 26(1), 112–120. 1. [CrossRef]

- Stemler, S. (2000). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 7(17). [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Transportation. (2022). Company Snapshot. https://safer.fmcsa.dot.gov/CompanySnapshot.aspx.

- Walter, S., Ulli-Beer, S., & Wokaun, A. (2012). Assessing customer preferences for hydrogen-powered street sweepers: A choice experiment. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 37(16), 12003–12014. [CrossRef]

- Winebrake, J. J., Green, E. H., Comer, B., Corbett, J. J., & Froman, S. (2012). Estimating the direct rebound effect for on-road freight transportation. Energy Policy, 48, 252–259. [CrossRef]

- Wong, N. (2022). Taking Charge: Supporting Small Fleets in the Transition to Zero Emission Trucks.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).