1. Introduction

Historical records reflect the day-to-day events of cities and states, but they also forcibly include whatever great trends affect the course of their history; a statistical analysis of the time series of these records can show us which watershed events occurred, and how they affected society

Blossfeld et al. (

2014). An analysis of population numbers, for instance, can show when a certain city of state reached its peak and try to relate it to certain specific event; an analysis of historical production of a certain raw material will show when it reached its peak but also when the introduction of technologies led to boosts in production.

In order to do that, we need to focus first in the history of specific states or nations, since otherwise it would be impossible to match statistically computed points of change to actual events, and we will focus on the Republic of Venice. This polity has been repeatedly studied in computational humanities research papers

Merelo (

2023);

Merelo-Guervós (

2022);

Molinari (

2020);

Smith et al. (

2021);

Telek (

2017), mainly due to the fact that it had for the bigger part of its history a well organized centralized bureaucracy, with very extensive archives, and these archives have been conserved for its most part. The history of the republic, however, starts in the late 7th century

Lane (

1973) and goes through many events that affected the history of the West: from the conquest of Constantinople in the 13th century, through the battle of Lepanto in 1571, to its eventual takeover by the French state in 1797.

More importantly from the point of view of this paper, its state was governed by a president of the republic, called

doge, who was elected for life among outstanding citizens of the Republic; initially by popular acclamation, then from the 12th century by a set of notable citizens

Maranini (

1927) and eventually, after the so-called

Serrata (or closure), representatives of a pre-established set of noble families

Ruggiero (

1979).

These nobles were moved by commercial as well as political interests

Sperling (

1999); thus, marriages in the republic of Venice were arranged institutions

Cowan (

2016a);

Cox (

1995), where the bride’s family had to pay a dowry to the groom

Chojnacki (

1975); noble families could only afford to marry off a single woman in their household, considering their marriage rather an investment, one that could possibly pay off in the near or far future in the form of administrative positions for grandchildren, political support for any cause they would be interested in or any appointment they aspired to (including becoming doges) and, of course, commercial partnerships that would keep or enlarge the family’s fortune. So political, social and historical events would certainly have an effect in the social status and fortunes of all patrician families, as well as in their total amount: the nobility status conferred just a position, not guaranteed wealth. This is why examining shifts, and detecting shift points, in the time series of marriages will give us insights on events of such an epochal importance as to change the whole social panorama of the Republic.

In this paper, we will try and answer the following research questions:

-

RQ1

Is there a statistically significant change point in the Venetian matrimonial time series?

-

RQ2

Is there a statistically significant change of trend in the number of marriages?

-

RQ3

Can we match these change points or change of trends to historical events?

-

RQ4

Can we validate these change points or change of trends with any other measure in the matrimonial time series?

And we will do so through the analysis of publicly available temporal series related to marriages in the Republic of Venice using robust statistical techniques such as change-point and trend analysis.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Next we will show the state of the art applying change point analysis to historical data, as well as the literature on marital practices in the Republic of Venice. We will then present the

dataset used in this paper. Next we will perform change point and trend analysis on the time series, and try to answer the research questions in two parts: first

analyzing the trends in the time series and then applying

change point detection algorithms. Finally, we will present our

conclusions and discuss its implications.

2. State of the art

Change point analysis has been extensively used in environmental, especially climate, studies

Beaulieu et al. (

2012); however, it has only recently been incorporated into the set of tools used in historical research. Recent papers, for instance, analyze how a natural event, Hurricane Harvey, created a shift in the number of crimes reported in the Houston area

Augusto (

2021). Change point analysis can detect underlying patterns; for instance

Yang et al. (

2021) was able to find out that the reduction in mobility brought by the Covid pandemic occurred

before any lockdown measures were taken; COVID pandemic was also the focus of

Shang and Xu (

2021), which analyzed excess deaths in Belgium looking for a change point, and discovered that these change points varied depending on the age group. It is especially interesting, in this sense, the paper

Fagan et al. (

2020) that analyzes historical battle deaths to find turning point in technologies or tactics that affected them; in that sense, change point detection becomes a true tool in the hands of historical researchers so that they can rank changes in battlefield methodologies according to the shift they provoke in the number of deaths, and thus in history at large.

Focusing on Venice,

Smith et al. (

2021) went in the opposite direction: first established a date in which the procedure of the election of doges was changed, and then showed that the time these spent in doges decreased extensively after that date. However, doges’ terms were researched using shift point analysis in

Merelo (

2023), finding that the change to elect older doges occurred, in fact, after the Serrata, thus finding that shift point analysis is able to identify events that produced significant shifts in the political landscape of the Republic.

This landscape, in general and in particular focusing on matrimonial politics, has been examined by a number of researchers; lately statistical analysis has been used extensively, for instance in

Telek (

2017) and of course

Puga and Trefler (

2014), which look at how the status in the social network of noble marriages matches their economic or political status, and how

tactical marriage allowed some families to improve their standing among the other families of the Republic. But these papers need to be supported by solid historical investigation, of which

Chojnacki (

1975) is the main source, and even proposes a possible shift point in the history of Venice: what they call the

third Serrata, the moment at the end of the 15th century when a law to restrict marriages between patricians and non-nobles was announced

Chojnacki (

2000)

1. Other papers

Cox (

1995);

Sperling (

1999) look in general at matrimonial politics from different perspectives, such as gender studies. Books such as

Cowan (

2016a) and

Hacke (

2017) look at other aspects of history, with the first one, in its chapter

Cowan (

2016b) looking at a particular moment in the history of Venice and how marrying with non-Venetians and non-patricians evolved after different events. This paper, as well as the previously cited

Chojnacki (

1975), prove that the number of marriages and its dynamics will be closely related to the number of marriages with non-noble families.

In the rest of the paper, we will try to apply statistical techniques to the analysis of the Venetian matrimonial time series. We will next present the dataset that will be using.

3. Dataset used

The dataset used was extracted from the Venetian Archivio dello Stato and released by Puga and Trefler for their paper

Puga and Trefler (

2014). Since marriages with a patrician man had to be registered at the Avogadori di Comun, the archive includes a very thorough registration of all marriages occurring since the late Middle Age up to a few decades after the fall of the Republic.

This dataset has been filtered in these ways:

Only those marriages that had a date have been considered; the rest have been dropped.

There were only a few marriages before 1398, probably due to registration problems, so they have been dropped.

The Republic of Venice ended in 1797, so all marriages in the dataset after that date have been dropped.

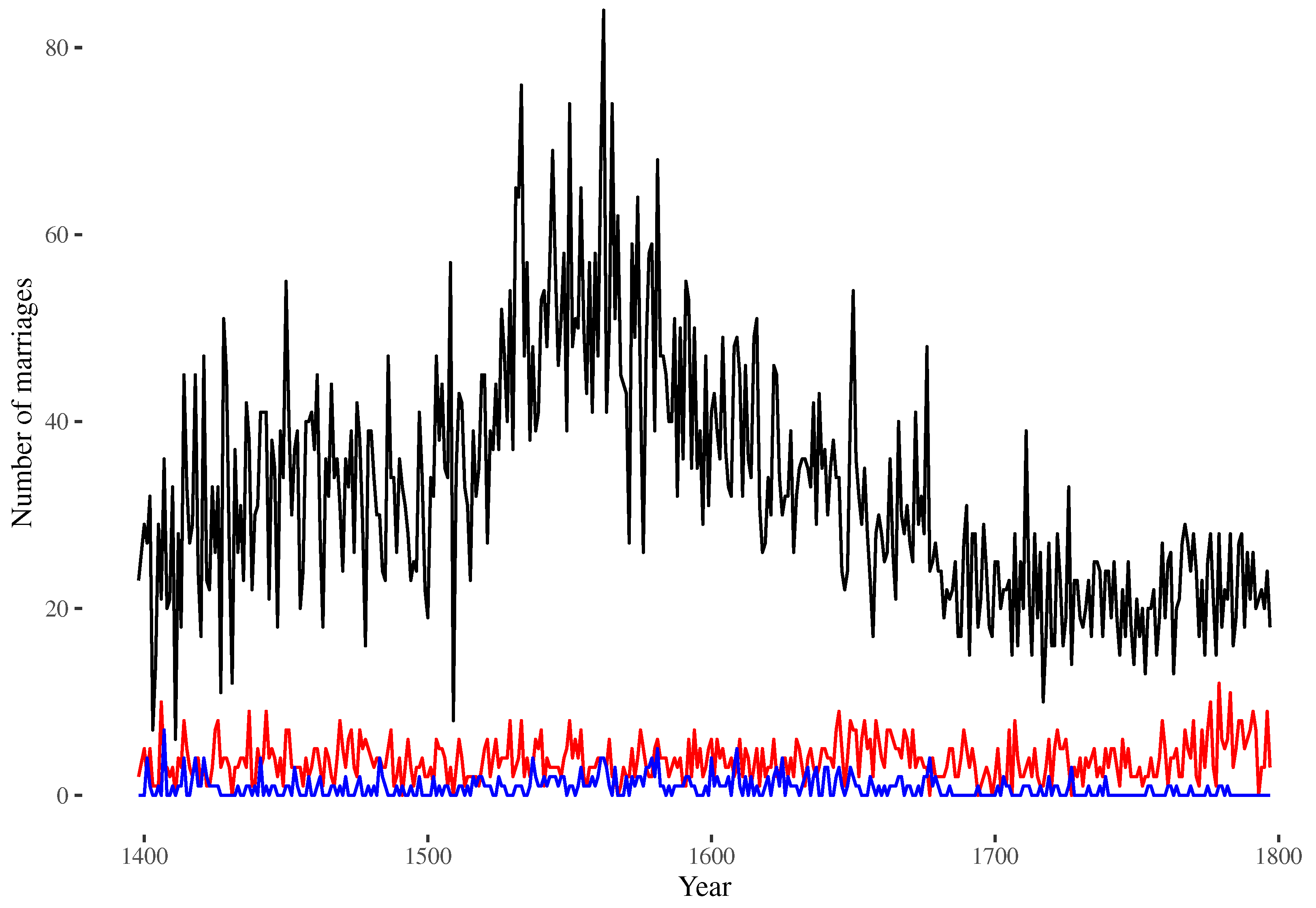

The resulting time series has 399 data points starting in 1398 and ending in 1797. The total number of marriages is 13019. In some cases, the wife does not belong to that closed set of noble families, which is why the normalized noble family name for them is an empty string; the total number of such marriages 1507. Additionally, there are 335 cases of intra-family marriages, where the wife and husband belonged to the same (extended) family. This time series is plotted in

Figure 1.

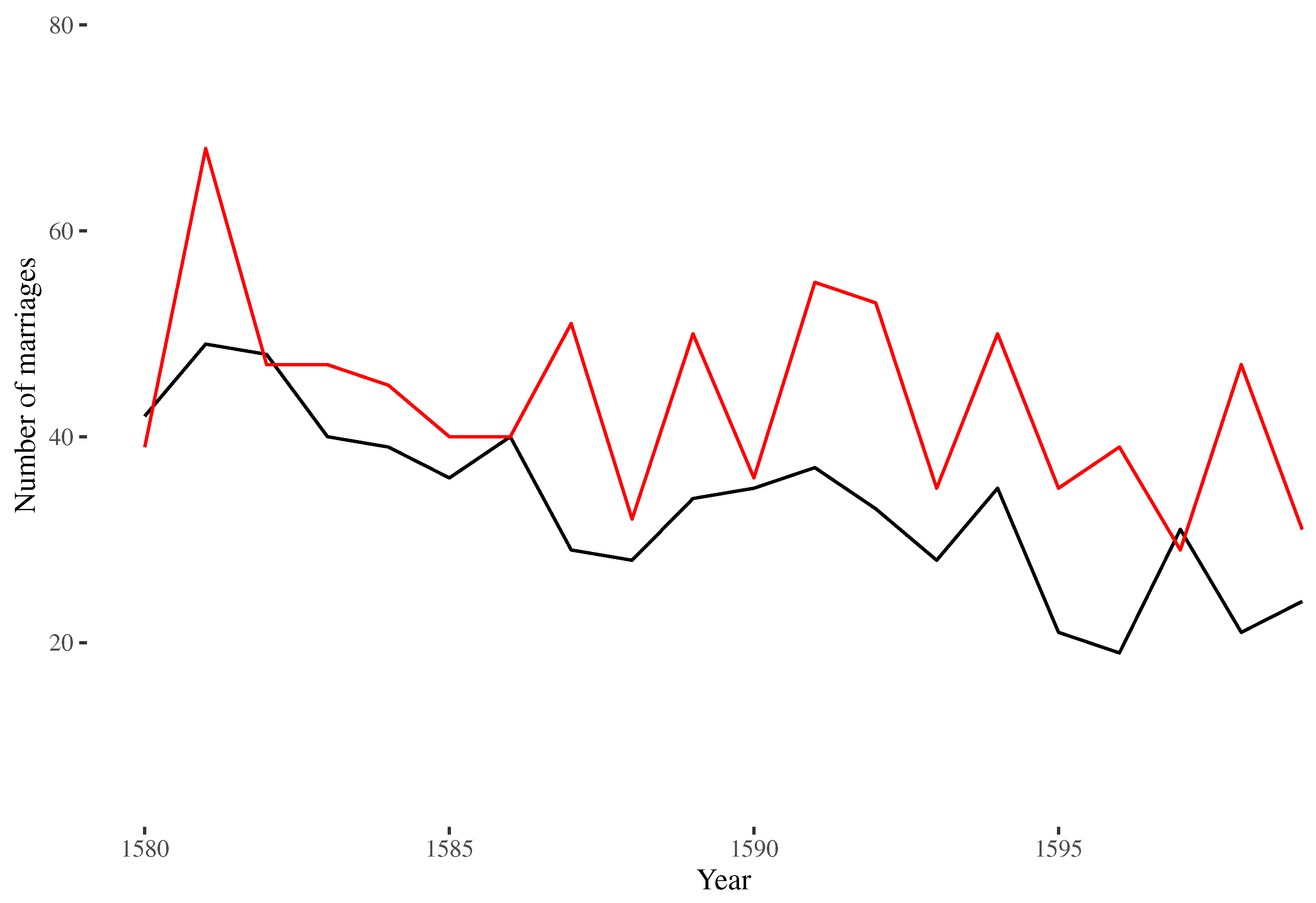

One way of validating these figures is cross-referencing them with figures published elsewhere. A limited number of years has been analyzed in

Cowan (

2016b), focusing on the presence of "outside" (i.e. non-patrician) wives. The data published in this book, Table 3.1, is plotted against the data used in this paper for the same period in

Figure 2; for reference, marriages including non-patricians have also been plotted in

Figure 1 as a first spot check of their importance in the series.

In general, the figures are in the same order of magnitude. The data used in this paper seems to have, also in general, more marriages than the data published in

Cowan (

2016b), and this might be mainly due to some marriages taking place in a different year than the contract; only in two occasions it is slightly higher (by one or two); given that the original data is nominal, with names of bride and groom, it is consistent that there are more in this dataset that in the paper quoted. Although it is not central to our paper, the amount of "outside" marriages is also similar in the same way, and at any rate in the same order of magnitude. The discrepancies detected should not be enough to invalidate the following analysis, at any rate. The data has been also validated by its use in several papers, the main of which is the one that published it

Puga and Trefler (

2014).

From this comparison, we can conclude that our data is sufficiently good, and does not seem to have any major bias; as a matter of fact, it is one of the datasets with the longest time span and with the best documented sources, allowing us to have unique insights into the working of a late Medieval-early Modern society.

4. Peak marriages in the Republic of Venice

We will first try to find long-term trends, as well as local periodicities or anomalies in the previously explained time series using the R package

anomalize. In the default configuration, it uses the STL method

Cleveland et al. (

1990) for seasonal trend decomposition. We will also apply a method for anomaly detection, in order to check either the existence of anomalous events, or anomalous registration of events.

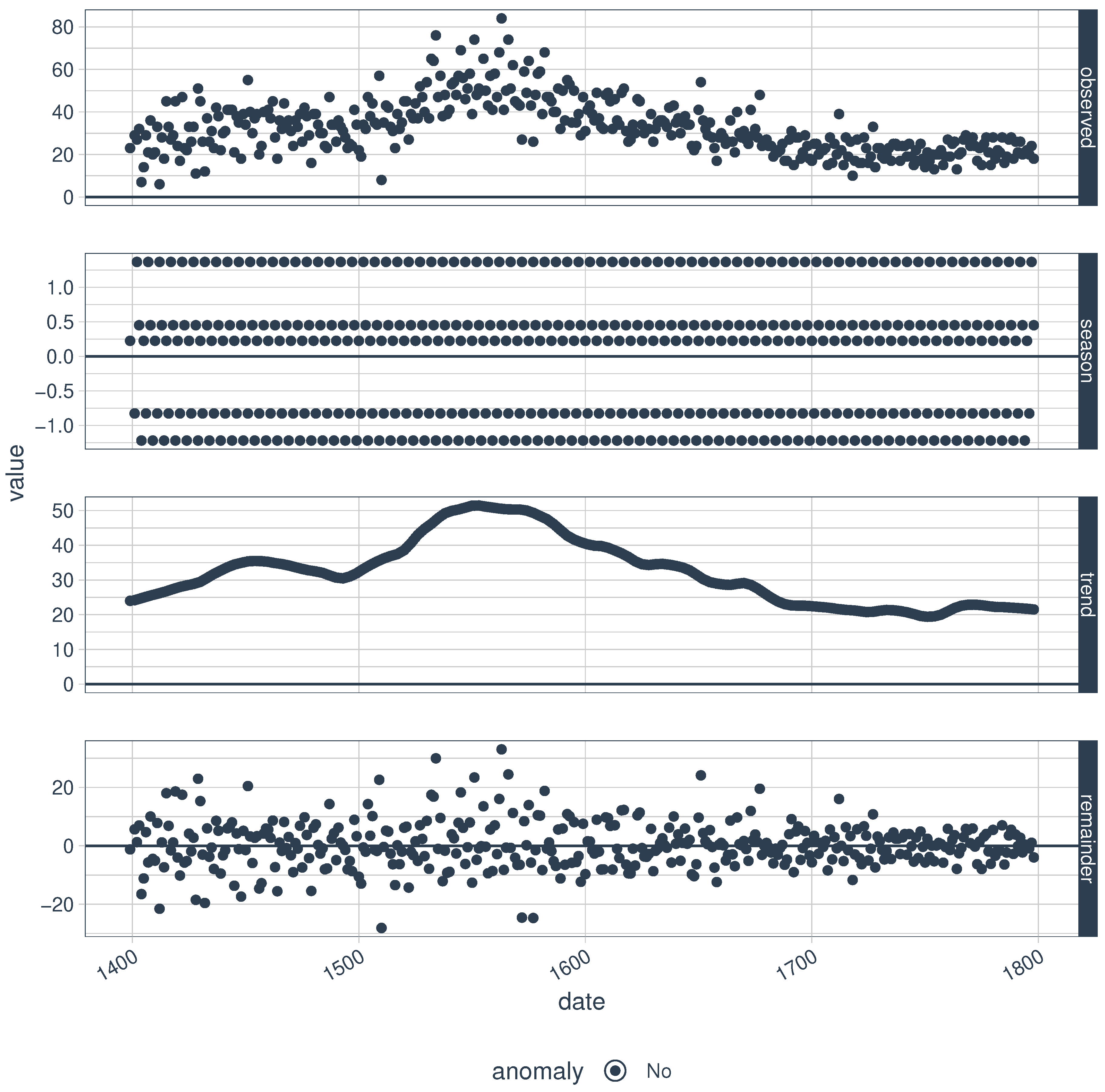

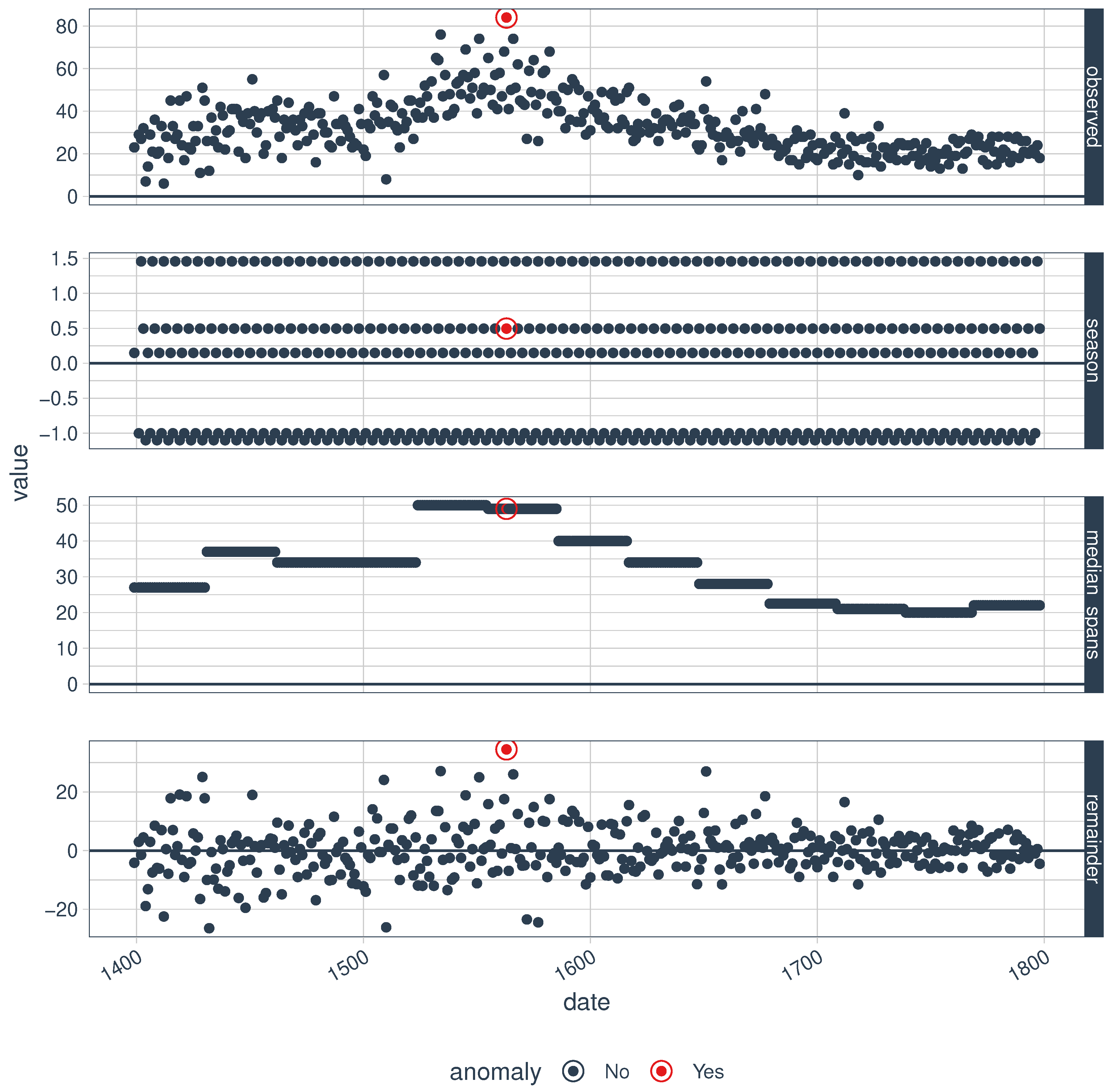

Figure 3 shows the analysis of the time series using the default method, which is STL as indicated above, plotted using the

plot_anomaly_decomposition function. From top to bottom, it shows the original series, the seasonal component, which follows a period of five years, with three years above trend and two years below trend; the trend component with a peak around mid-16th century, and the remainder, which is the original series minus the sum of the previous two components. Any anomaly using this method would be shown as a circled red dot; in this case, there are no anomalies detected. The trend smoothing, which is computed automatically by this method, is 30 years.

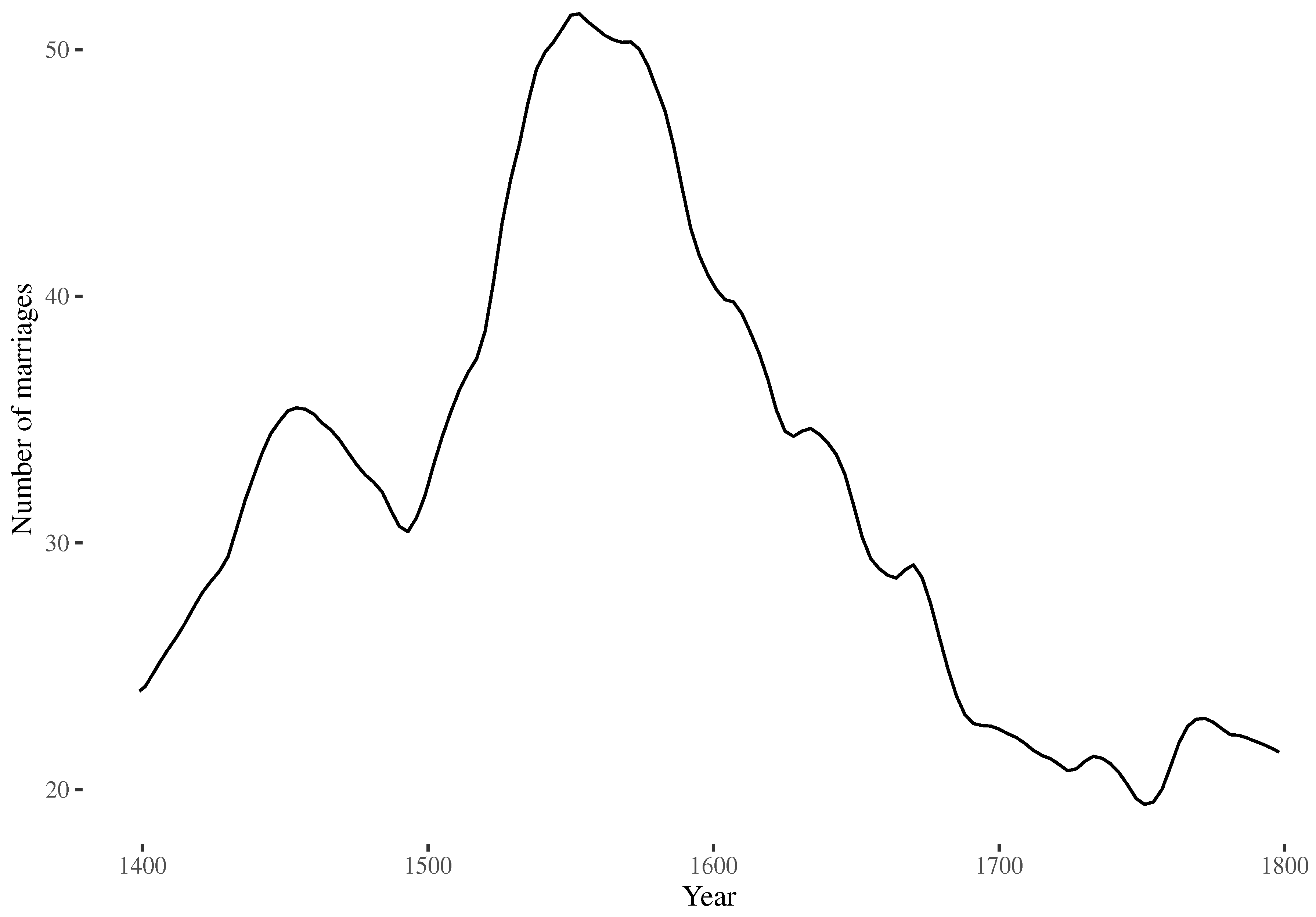

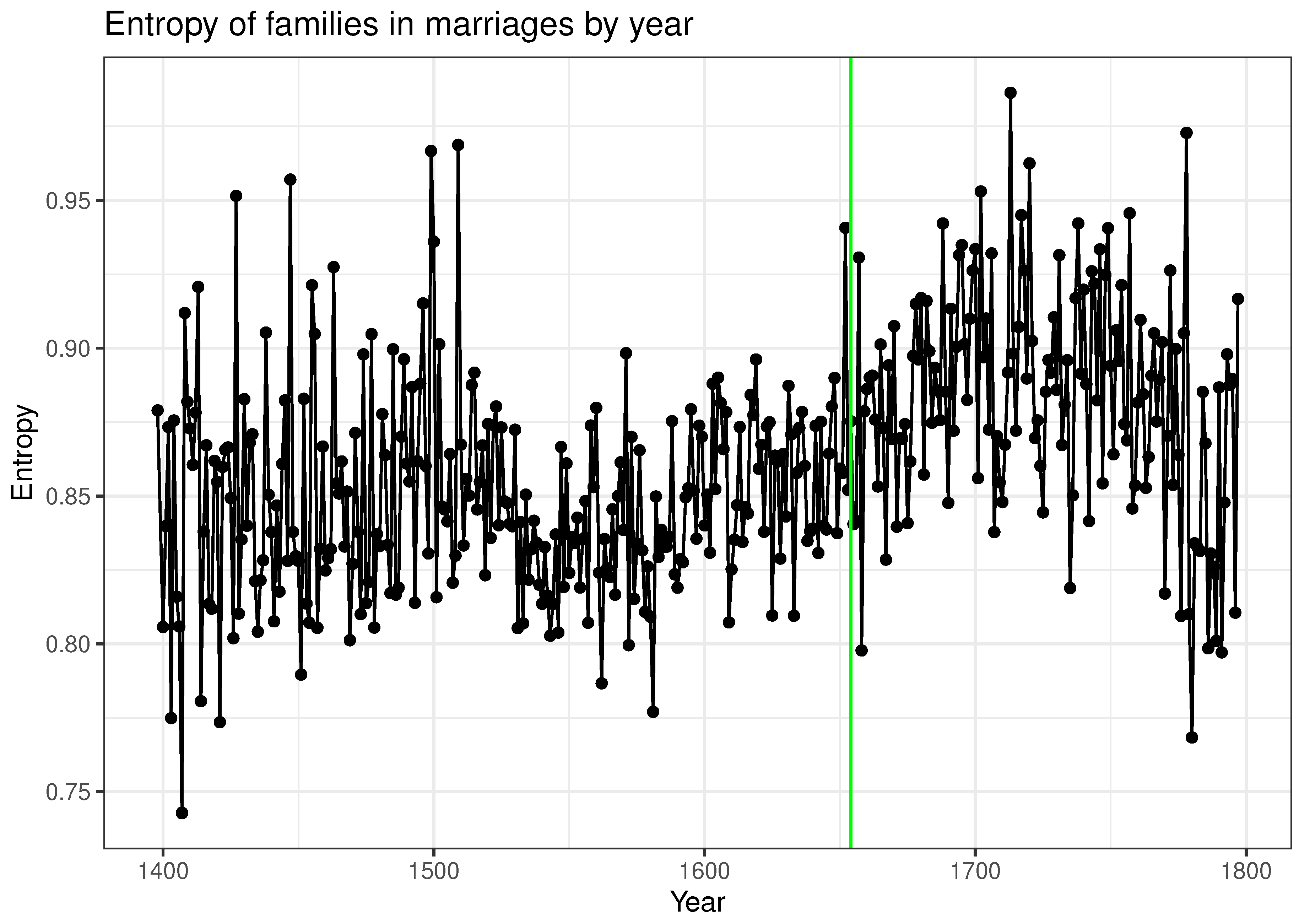

The trend peaks in 1552, with a value of 51.4538416 marriages. We show this trend chart by itself in

Figure 4.

The trend is seen to rise sharply from the beginning of the 16th century, reaching the indicated peak, with another peaklet a decade later; from then on, the decrease is quite clear, with only a very small peaklet, which is indeed lower than even the initial value of the series, towards the late years of the Republic.

Using this analysis, let us try to answer research question 2: is there a statistically significant change of trend in the number of marriages? There clearly is one by the mid-16th century. To validate this, we will use a different trend analysis method, this one generically called "Twitter"

Vallis et al. (

2014), which uses a different statistical method to estimate trend based on the median. Using the same function as before, this is shown in

Figure 5

In this case, the maximum is 50, clearly similar to the previous one; as a matter of fact, the year where the previous analysis found the trend peak, 1552, is the next-to-last year of the period with the highest trend value in this analysis, which goes from 1523 to 1553. The trend smoothing period is in this case 31 years, as opposed to the 30 years of the previous method, but the seasonality is again 5 years with the same patterns as before. This method, however, does show a single anomaly in the year 1562, which is the actual peak value of the time series, with 84 marriages. In neither analysis this is the actual peak, although in the previous one it would part of the seasonality component, whereas in this case it would be slightly beyond it. Both analysis, however, coincide in the existence of a peak in the mid-16th century, thus answering positively to research question RQ2.

From the point of view of historical research, it is even more interesting to answer RQ3: is this change of trend associated to any historical event? It is evident that in most historical states events happen every single year and it might be impossible to find a single year where nothing relevant happened; however, we will have to restrain ourselves to try and find actual historical causes that might have originated this peak. Taking into account that marriage can be considered a market

Becker (

1973), it is quite clear that the number of marriages will depend on the supply of available (noble) males. There is no single source we can check for this, although

Statista (

2016), which cites

Maddison (

2006) as its source, mentions 1557 as the year where Venice reached the peak of its population, of around 158000 persons. Not all of them, however, were nobles, and the proportion of nobles to the total population might vary widely, so we need to look at

Todesco (

1989), which looks at different sources, including the registers from the Maggior Consiglio (supreme legislative council of the Republic, which included representatives of all the noble families). In that paper, chart number 2 shows a slow decline of the number of nobles that vote from 1500 on, with small peaks later in the 17th century; the peak of the number of voting nobles would be somewhere in the late 15th century or early 16th century. Additionally, Table 5 in the same paper shows a census of "male nobles" with its peak at 1563 (the first year shown). Graph number 5 in the same paper shows a peak in the population of Venice in the same year, 1563.

Research Question 3 can, then, be answered positively: this peak in the number of marriages in the Venetian time series precedes by a few years the peak in overall population (according to several sources), as well as the peak in the number of nobles in the census, which is only to be expected since marriages must precede births. On the other hand, this also confirms the validity of trend analysis as a tool for historical research.

This is, however, a short and not entirely satisfactory answer, since peak population, even peak noble population, is not, by and itself, an historical

event; clearly both facts must be caused by another event that can be considered as such. The Ottoman-Venetian war, that started in 1570

Burkiewicz (

2022), can be rather seen as a consequence of a perceived weakness of the Venetian Republic, rather than the cause. And while it would be relatively easy to find causes of dips in population (plagues, wars), causes of peaks are more difficult to individuate. The history of Venice in the first half of the 16th century

Lane (

1973) is rather uneventful after the war of the League of Cambrai. The timeline features a succession of doges with no other event; during the Turkish War of 1537-40 Venice was simply a minor allied of the Spanish emperor. However, an undercurrent of economic irrelevancy was flowing since the take over of spice trade by Portuguese merchantmen during the same period. Galley trade ground to a halt during those times, and territorial expansion reached its peak in 1509. 1556 saw the creation of the

provveditori sopra luoghi incolti (also

beni inculti) to put land in

terraferma, that is, the part of the Republic that included the northern provinces in Italy. According to some authors, there was a famine and plague by the end of the Venier doge tenure, in 1556. So that might have been the tipping point that caused the demographic decline of the Republic, exacerbated by the war of Cyprus and subsequent plagues.

Consequently, the longer answer to RQ3 is that the peak in the number of marriages matches the peak in economic performance of the republic as well as slightly precedes the onset of a series of wars and famines that definitely caused that peak in noble marriages to never be reached again.

Change point detection, however, is a technique that works with long-term economic, environmental and social changes, and might discover other turning points in Venetian history. We will analyze them next.

5. Detecting change points in matrimonial time series

In general, change point analysis will detect epochal changes in time series, based on different aspects of it: average or median, or standard deviation; what we will be looking in this paper are changes in averages. A change point will occur when the differences between averages before and after the change point are maximized

van den Burg and Williams (

2022). Several different algorithms can be used for this, with

Lanzante (

1996) and

Pettitt (

1979) being two of the most popular. All of them are included in the package

trend Pohlert (

2020), which we will be using in this paper.

We have thus used Lanzante’s test to find a single change point in the sequence with the yearly number of marriages, and found that point to be at 1654. We can also use Pettitt’s test, which finds a change point at 1654, thus validating the previous one. IN both cases the p-value is very small, indicating that the change point found is statistically significant. The average number of marriages before the change point is 38.0588235; after the change point is 23.0138889; after the change point there are, on average, 15 marriages less per year, indicating a significant change in the trend. This, again, answers positively research question 1. Research question 4 is also answered positively, since we are validating the change point by two different measures.

It would be interesting to look at the data set from another point of view: the entropy of the sequence of marriages. We will be computing entropy over the frequencies of families appearing as bride or grooms in a specific year. Entropy is a measure of the amount of information, or surprise, in a group of data. If a single family appears, then the set is totally ordered and predictable, and that would yield the lowest entropy; many different families appearing only once would have the highest entropy; anything in between (less families appearing only once, more families with a random amount of appearances) will have any value in between. Since entropy will be influenced by the number of different marriages in a year, we will normalize this entropy, dividing by

, where

N is 2 times the number of marriages in a year, that is, the number of persons appearing in marriages in a year. Normalized entropy will go from 0 to 1, in this case. This normalized entropy is charted in

Figure 6, with the already computed change point marked as a vertical line.

We will try and answer RQ4 by measuring the change point in this specific series.

We will be using only Lanzante’s test, since the rest have yielded the same value before; this tests finds a change point at 1645, 9 years before the previous one computed. The average value of entropy before the change point is 0.8478995; after the change point is 0.8817361. This would answer the question with a qualified yes; they are close enough to be caused by the same event, or at least to have a cause-effect relationship, namely, changes in average entropy (in the surprise) of marriages will cause an eventual decrease in their number.

At any rate, entropy is a quantitative measurement, but it cannot be a cause of the change in regime. One quantity that is included in the data set is the number of marriages with non-patrician wives; after the so-called third Serrata, women had to undergo public examination by the Senate, so it might be an important source of entropy in the data set.

We will work with the percentage of marriages that included a non-patrician wife, instead of the absolute number, which will give us a more precise estimation of its impact in the time series. In this case, the change point is detected at 1638. The average percentage of marriages with non-patrician wives before the change point is 9.88%; after the change point is 16.94%. Again, this change point occurs 7 years before the previous one; again, it is statistically significant, and as a matter of fact, it indicates a year where the number of marriages with non-patrician wives doubled with respect to the previous value. This answers the concerned research question positively, with caution: from 1638 to 1654 a change in the regime of marriages in the republic of Venice took place, causing higher entropy, higher number of marriages with non-noble wives combined with an overall lower number of total marriages.

Since we are looking at several variables at the same time, we should try and use a multivariate analysis of the change point. For that purpose, we are going to use the

ecp package

Nicholas A. James et al. (

2019), which includes several algorithms for non-parametric multiple change point analysis

Nicholas A. James and David S. Matteson (

2014). As a bonus, its included algorithms are able to detect multiple change points in a time series.

We are going to use the procedure

e.divisive which implements a hierarchical divisive estimation procedure

Nicholas A. James and David S. Matteson (

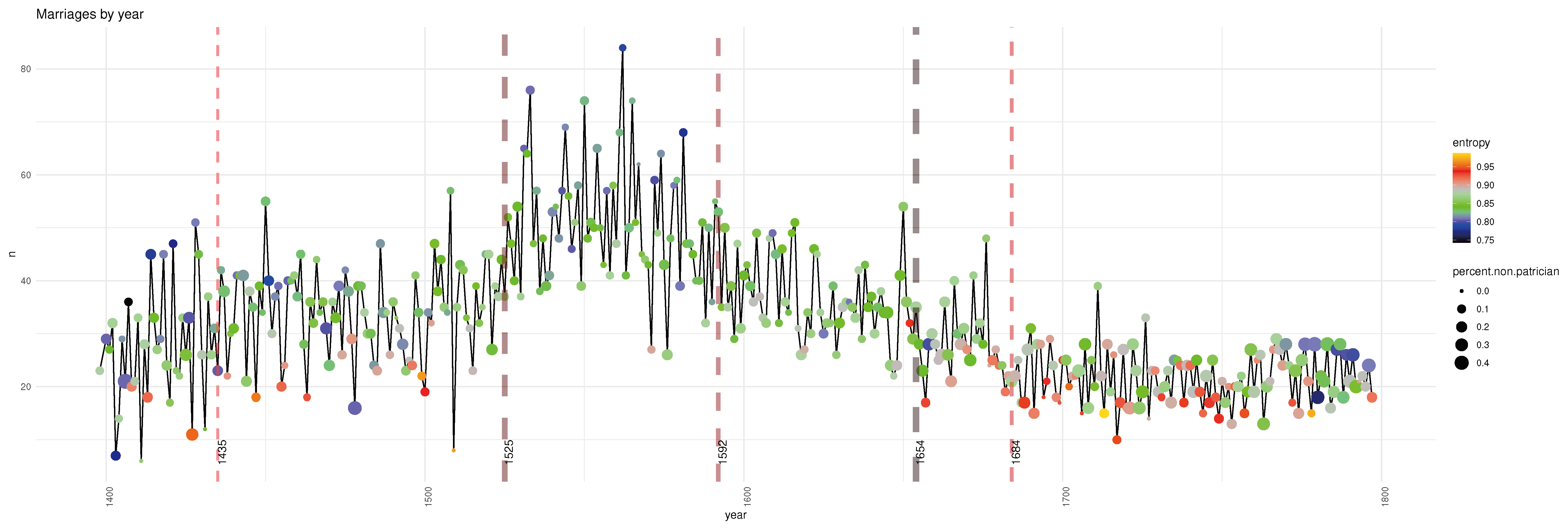

2014); it essentially iteratively applies a procedure to locate change points in the whole series, and the fragments created by them. This procedure results in a total of 3 change points, which are located at 1654, 1525, 1592, 1684, 1435, sorted by importance. This multivariate analysis confirms the year 1654 as the one where the main change point takes place, but also finds a series of other significant change points: 1525, 1592, 1684, 1435, which are interesting by and of themselves. We plot the whole time series and change points in

Figure 7.

This visualization of the results enables the appreciation of differences before and after the main change point, and between them. We can see, for instance, how the number of marriages essentially decreases after it, while before there were more ups and downs. There is bigger abundance of "big dots", representing a high percentage of non-patrician marriages, after the change point, and the color of those dots tends toward "warmer" colors such as red and orange, over all in the years with less marriages; years with more marriages tend towards green (entropy around 0.85), while before they were darker; years with many marriages tended to have, paradoxically enough, lower entropy.

Let us not forget, however, the four research questions. We can answer positively RQ1: there is a statistically significant change point in the time series, and it is placed in 1654, according to multivariate change point tests as well as univariate change point tests applied to the series of number of marriages; the other two series analyzed yield change points that are also statistically significant, and close to it; if we want to declare a "confidence interval" we can say that there is a change period, rather than a point, between 1638 and 1654. This change point shows clear changes of trends in the number of marriages, its entropy and the percentage of non-patrician marriages, answering RQ2, as we have already shown. The measures have been cross-validated using different measures for a single variable, and also using multivariate analysis, answering RQ4.

We need to answer RQ3: can this change point be matched with some historical event? The years of this change period fully fall within what was called

war of Candia, or fifth Ottoman-Venetian war

Lane (

1973);

Mason (

1972). This war started with skirmishes in 1638, to reach its full-blown phase in 1644. It lasted until 1669, with its last phase consisting mainly in naval battles and the siege of Candia itself, nowadays Heraklion. Although the Ottomans took heavy losses, Venice lost 30000 men, many of them nobles

3. That will certainly account for the decrease in the number of marriages. But wars in general had another effect:

Raines (

2003) mentions that new families were included into the nobility

per soldi, that is, simply paying their seat in the

Maggior Consiglio, 75 families in all, which account for the increase in entropy: their presence will add to the number of different families participating in marriages during those years. With the loss of Candia, its cash crop, cotton, and the decrease in commerce, there was a general relaxation of matrimonial laws together with the vanishing of the fortunes of the noble families. Marrying a non-patrician meant, for these impoverished noble families, an injection of cash and commercial relations that could allow the

casata to survive a bit longer. This would answer RQ3, and highlight how statistical analysis of time series, coupled with historical analysis, allows us to go beyond qualitative speculations to enter into quantitative proofs of historical social and economical phenomena.

Table 1 summarizes the values of the different quantities examined in the time series by period between change points found by the multivariate analysis. We can again try and answer the third research question: can we match these periods to historical events in the Republic of Venice? We will examine each in turn:

First period, 1399-1435: this period has middle values of entropy, low number of marriages, and a medium number of non-patrician marriages. It ends a few years later than what Chojnacki called the

second serrata Sperling (

1999), which required every candidate to new member of the Consiglio to be presented by his father. Although this might seem like a minor requirement, this measure was accompanied by a series of sumptuary laws, but more importantly by a bureaucratization of all processes related to marriages, including dowry contracts.

Second period, 1435-1525. The introduction of the laws mentioned in the previous period caused an increment in the number of marriages, no change in entropy, but mainly resulted in a decrease of the marriages that included a non-noble partner.

Third period, 1525-1593: a period that starts with the

second serrata, and ends with the already mentioned third Serrata. This second enactment of legislation implied that nobility started with birth, since marriages had to be approved by the Senate. Effectively, the main feature of this period is the lowest average percentage of non-patrician marriages, which was accompanied also by a low entropy: the restriction in the possibility of marriages entrenched and stabilized the existing families. The number of marriages reaches the peak, and in fact, as indicated in

Section 4, the year with the highest number of marriages is found in this period.

Fourth period, 1593-1655: the period starts with the second weakest change point in the series. The number of marriages decreases, entropy increases slightly, and the number of non-patrician marriages increases. This is a case where it is not clear what historical event might have caused the change point. The loss of Cyprus and several plagues occurred some 20 years before. Might be the conjunction of demographic and economic factors that caused this shift.

Fifth period, 1655-1684: the onset of this period is caused by the biggest change point detected in the series, which has already been explained. The entropy increases together with the number of non-patrician marriages, while the total number of marriages decreases. The war of Candia takes its course during this period, as well as the first War of Morea, started in 1684. Although it acquired some territories, it costed between 10 and 15000 persons to the republic, giving pace to the last period of the republic.

Fifth period, from 1684 to the end of the Republic: the number of marriages reach its lowest value, entropy and percentage of non-patrician marriages are highest. The republic never recovered.

This list gives the longest answer to the research question 3, whether shift points match historical events. In two cases, shifts were provoked by changes in legislation; the others were caused by external events (mainly conflicts), but supported by legislation (the fact that citizens could become nobles by paying a fee, for instance). Technological and other changes are in the background, but, by themselves, cannot cause a shift in a time series of social data such as this one. There is a single shift point, of lesser importance, that cannot be easily explained, but it is probably due to the fact that it signals a transition from a period of growth (until the peak of marriages) and a period of stagnation and finally decline.

In general, it can be stated that external events affect mainly the number of marriages, while legislation affects the diversity of the marriages: how many different families are involved in them in a given year, and how many of them are non-patrician.

At any rate, using multi-change point analysis allows a more natural division of the history of a certain state of region in periods, focusing on the effects of internal or external events (or combinations thereof), rather than on (possible) causes without demonstrated effects.

6. Discussion and conclusions

The initial intention of this paper was to apply rigorous statistical techniques to find epochal changes in the history of the Republic of Venice. We used a well documented dataset of marriages by members of the nobility. A priori, using a time series that represents a social (and, in the case of Venice, also commercial) the occurrence of an event need not have information, or bear the effects, of what happens in the society at large. However, in this paper we have proved that, in general, analyzing using precise statistical techniques that time series we can obtain insights on the inner mechanism that drive a society to its summit, and eventually to its demise.

This is probably due to the fact that Venice was an aristocracy, a democracy of sorts ruled by the nobility, but also governed and administered, and even conducted in war, by the same aristocracy. Social mobility within the nobility, but also from the popolani or citizens to access the highest social level in the republic constitute a big part of the internal dynamics of the state, and marriages represents, in this case, the main mechanism to achieve this mobility. This explains why change points, and change in trends, can be easily matched to well-documented events in the history of the Republic.

Generalizing this result to other societies goes beyond the scope of this paper. It is very likely that if a dataset is able to capture the main social mechanism in a state or region, that region is relatively closed to external influence, and the dataset is not biased or complete, a division of the history in epochs could be performed. Certainly, using numerical analysis seems a better tool than qualitative appreciations, or other assumptions like the importance of a certain state ruler or technology. Using mono-variate single change-point or multi-variate multiple-change points have been proved to be, in this paper, a useful tool in that sense.

The dataset used in this paper represents a social network, and it was analyzed as such in the paper it was published. However, the results of this paper encourage the division of that social network in different epochs, with differentiated study of the usual micro- and meso-structure measures. That could give us insight on the actual families that drove those changes, or rode their wave, and give us also a better understanding of the social dynamics of the republic. That is left, however, as future work.