1. Introduction

One of the the most serious threats facing Spanish and global public health is the emergence of infections caused by bacterial strains resistant to antibiotic treatment. Today, there are bacterial species resistant to the full range of antibiotics currently available, which represents a potential medical disaster. The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that, without coordinated proactive actions among all countries, by 2050 there will be more deaths from antimicrobial resistance than from cancer [

1].

The use of antibiotics in dental procedures represents 10% of the total prescriptions (a not insignificant percentage: one billion daily doses of antibiotics received by the population) [

2]. The main responsible for this increase in resistance is inadequate prescribing by the health professional [

3]. However, the factors influencing inappropriate use do not only involve healthcare personnel, but also social policies such as lack of control in the sale of antibiotics, lack of knowledge and attitude of patients about the use of antibiotics and self-medication. In daily clinical practice, dental decisions are often motivated by the patient's attitude [

4]–[

7]. Sometimes, the pressure exerted by the patient or companion can lead the dentist to inappropriately prescribe antibiotics to please the patient. Therefore, it is very important that the general population is well aware of the role of antibiotics in the treatment of endodontic infections, as well as the implications that their inappropriate prescription has on the development of bacterial resistance. In addition, there are prescriptions "just in case" or out of fear of complicating the procedure [

7].

For this reason, the European Commission undertook a series of surveys among the general population to monitor their awareness and levels of use [

8,

9]. There is evidence that antibiotic prescription in endodontics is inadequate [

10], however, there is no evidence of the population´s knowledge in this area. So, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the perception of patients regarding the need to use antibiotics in endodontics, in order to promote educational strategies focused on the correct use of antibiotics in the community.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study populations.

In this cross-sectional study, 550 patients were asked to respond to a survey conducted on Google forms on the perception of systemic antibiotic use in the treatment of endodontic infections and antibiotic resistance. The survey was carried out between the months of January 2022 and March 2023. Inclusion criteria were that participants were not in possession of a dental degree.

To improve the study of the responses, we divided the participants according to whether they had a low/medium or high level of education. Within the educational level low/medium we incorporate people: without studies, possession of compulsory primary education (school graduation), compulsory secondary education and general high school. Within the respondents with a high educational level, we found people in possession of a certificate of professionalism, higher grade training cycle, university degree, university postgraduate degree and doctorate.

2.2. Questionnaire

The survey questions were adapted from those asked in a previous survey conducted in Barcelona on patient perception of antibiotic use after tooth extraction [

7] In addition, questions on antibiotic resistance were added. The questionnaire [Supplementary 1] was reviewed by dental researchers and professors of the Postgraduate Course in Endodontics at the University of Seville for appropriateness and clarity of the questions. Patients who participated in the survey did so anonymously, voluntarily and without compensation. The survey was satisfactorily completed by 514 from 550 patients, who were included in the study.

The socio-demographic variables of gender, age of participants and educational level were collected. In addition, participants were asked if they had ever received a root canal (yes/no). The remaining questions in the questionnaire cover issues of attitudes and knowledge about the use of antibiotics.

Before endodontics, do you think it is necessary to take antibiotics? (yes/no)

After the root canal, do you think it is necessary to take antibiotics? (yes/no)

If the dentist does not prescribe antibiotics, why doesn't he/she prescribe them? (yes/no)

If the practitioner does not prescribe antibiotics, would you seek out another doctor to ask why your doctor does not prescribe antibiotics? (yes/no)

If a dentist tells you that you have a dental infection, would you expect him/her to prescribe antibiotics? (yes/no)

If you have dental pain, do you expect the dentist to prescribe antibiotics? (yes/no)

Have you ever self-medicated with antibiotics for dental pain? (yes/no)

What do you think are the benefits of antibiotics? You can choose more than one option (Reduces pain, Reduces inflammation, Reduces infection, Improves oral health, No benefit, I don't know.)

What adverse effects do you think the use of antibiotics can cause? You can choose more than one option (Nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, fungal infection, allergic reaction, none of the above, I don't know.)

When you take antibiotics, for how long do you take them? (1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, others)

Do you know about "antibiotic resistance" (a process caused by the overuse of antibiotics)? (yes/no)

The Cronbach's alpha coefficient obtained was α = 0.770, indicating good internal consistency [

11].

2.3. Data collection and statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated to achieve a power of 0.95, with an alpha error of 0.05 and an effect size of 0.2 (test method: Chi-square test, G*Power 3.0.10, Franz Faul, University of Kiel, Germany). A total of 400 participants were necessary. The sample size was increased by 30% to account for potential losses.

A first exploratory descriptive analysis was performed, including qualitative and quantitative variables. The distribution of variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For hypothesis testing, the chi-square test or the Fischer exact test was used. All data were expressed as frequencies and their corresponding percentage. All analyses were performed using SPSS ® VERSION 25.0, considering significant differences when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Participation and description of respondents

The demographic data of the 514 patients are described in

Table 1. Female respondents (n = 339) accounted for 65.95 % and male respondents (n = 175) accounted for 34.1 %. The majority of respondents were aged ≥ 40 years (54.7 %). The educational level of the respondents varied widely, with a university degree being most prevalent (29.2 %), followed by higher education (21.6 %). Respondents with a high level of education represented 67.1 % of the population. Of the total number of participants, only 200 people (38.9 %) had ever had root canal treatment (RCT).

3.2. Perception of the need to take antibiotic before and after endodontics treatment

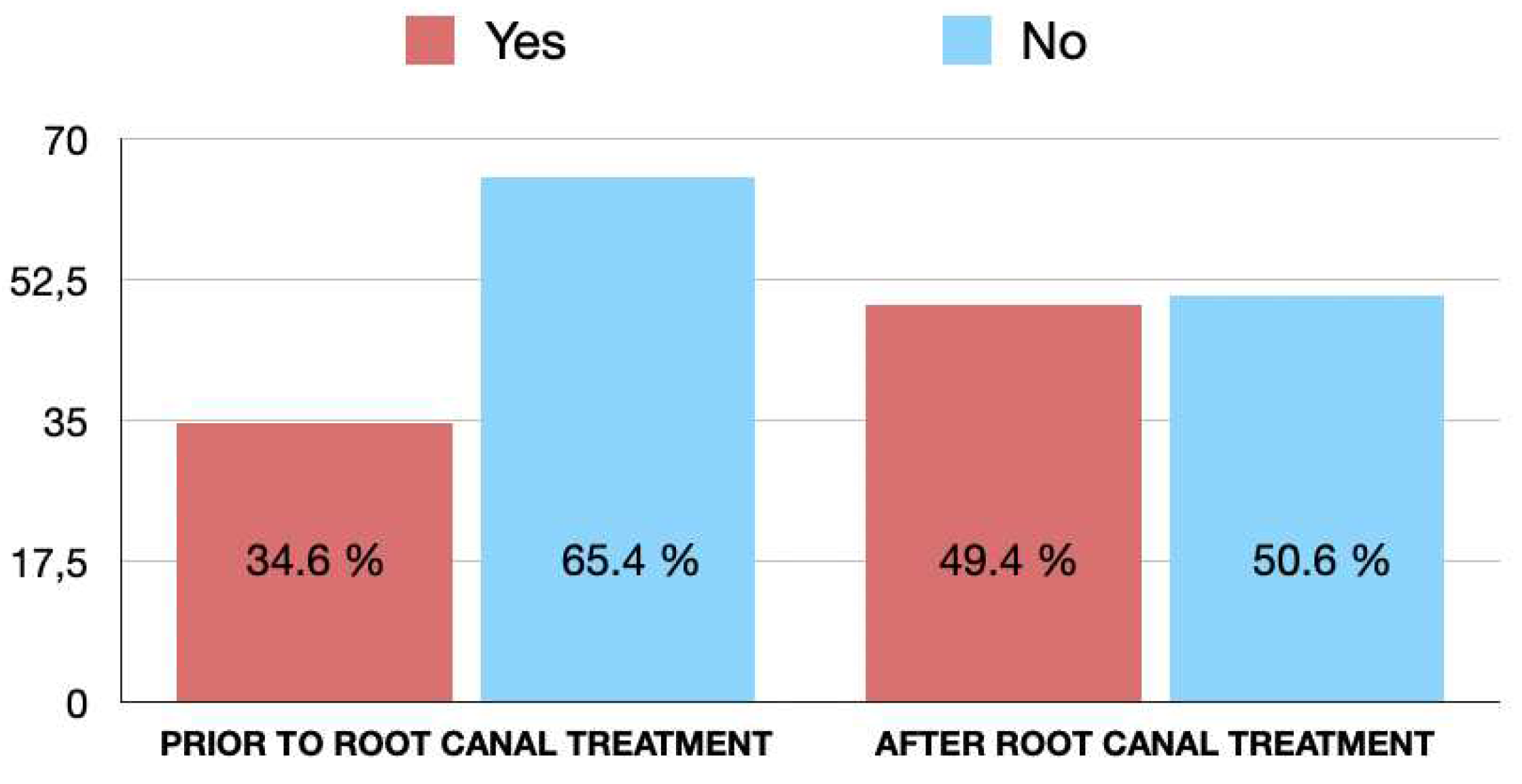

Figure 1 represents the patients' perception of the need to take antibiotics before or after RCT. While 178 respondents (34.6%), think that it is necessary to take antibiotics prior to RCT, 254 (49.4%) consider that they are necessary after it, regardless of the symptoms. Amongst the respondents who considered necessary to take antibiotics before RCT, the majority were women (n= 112; 33%), but there were not significant differences by gender (OR = 1.23; 95% CI = 0.84-1.80; p > 0.05). There were also no significant differences regarding the age (p > 0.05) or educational level (p > 0.05).

Among the people who considered it necessary to take antibiotics after RCT, no significant differences were observed regarding gender (p > 0.05), age (p > 0.05) or educational level (p > 0.05).

3.3. Participants´perception and knowledge of dental infection.

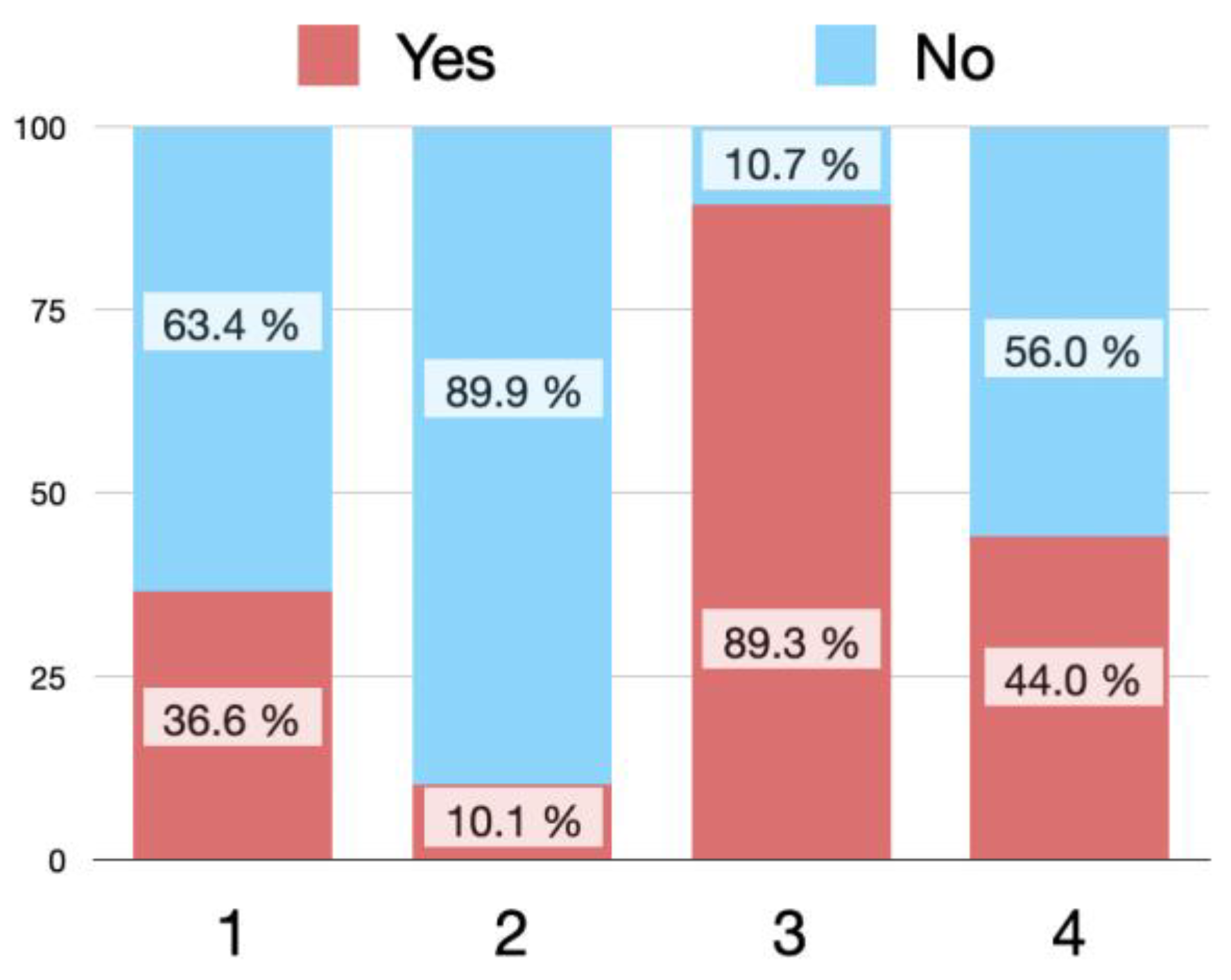

Figure 2 shows the answers of the participants to different questions on dental infection and antibiotic therapy.

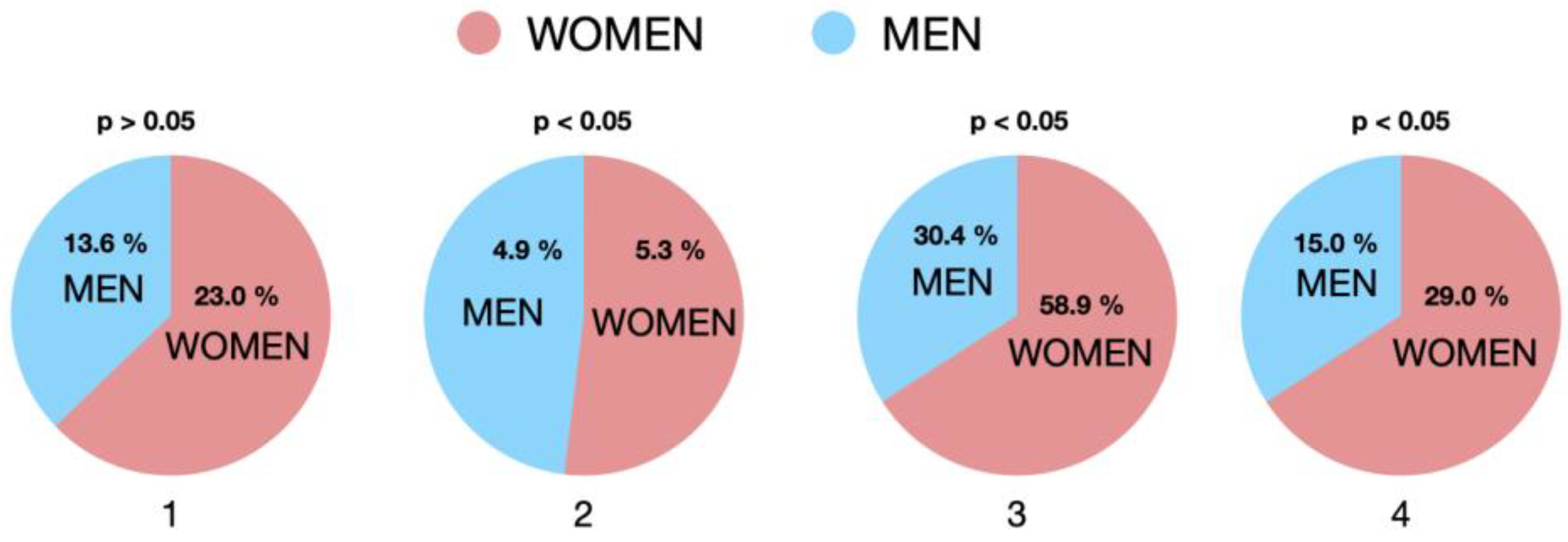

Faced with the clinical situation of having to undergo RCT, if the dentist does not prescribe antibiotics, 36.6 % of respondents would ask why he does not do so, and 10.1 % of the patients would even turn to another dentist to ask why antibiotics had not been prescribed, most of them were women (p < 0.05) (

Figure 3). Men were more likely to seek a second opinion than women (women 8% versus men 14%; p=0.024).

Amongst respondents, 89.3% expect to receive antibiotic therapy to treat any dental infection, most of them were women (p < 0.05). And 44.0 % thought that dental pain would be reduced with antibiotic therapy, most of them were women (p < 0.05).

With respect to age, a higher level of skepticism was observed in those under 30 years of age, as they would seek a second opinion as well as ask why they were not sent antibiotherapy compared to the rest of the age groups (p < 0.05). Similarly, the lower educational level has a higher perception of the need for antibiotherapy prescription after endodontic treatment and the need in the case of not being pre-written.

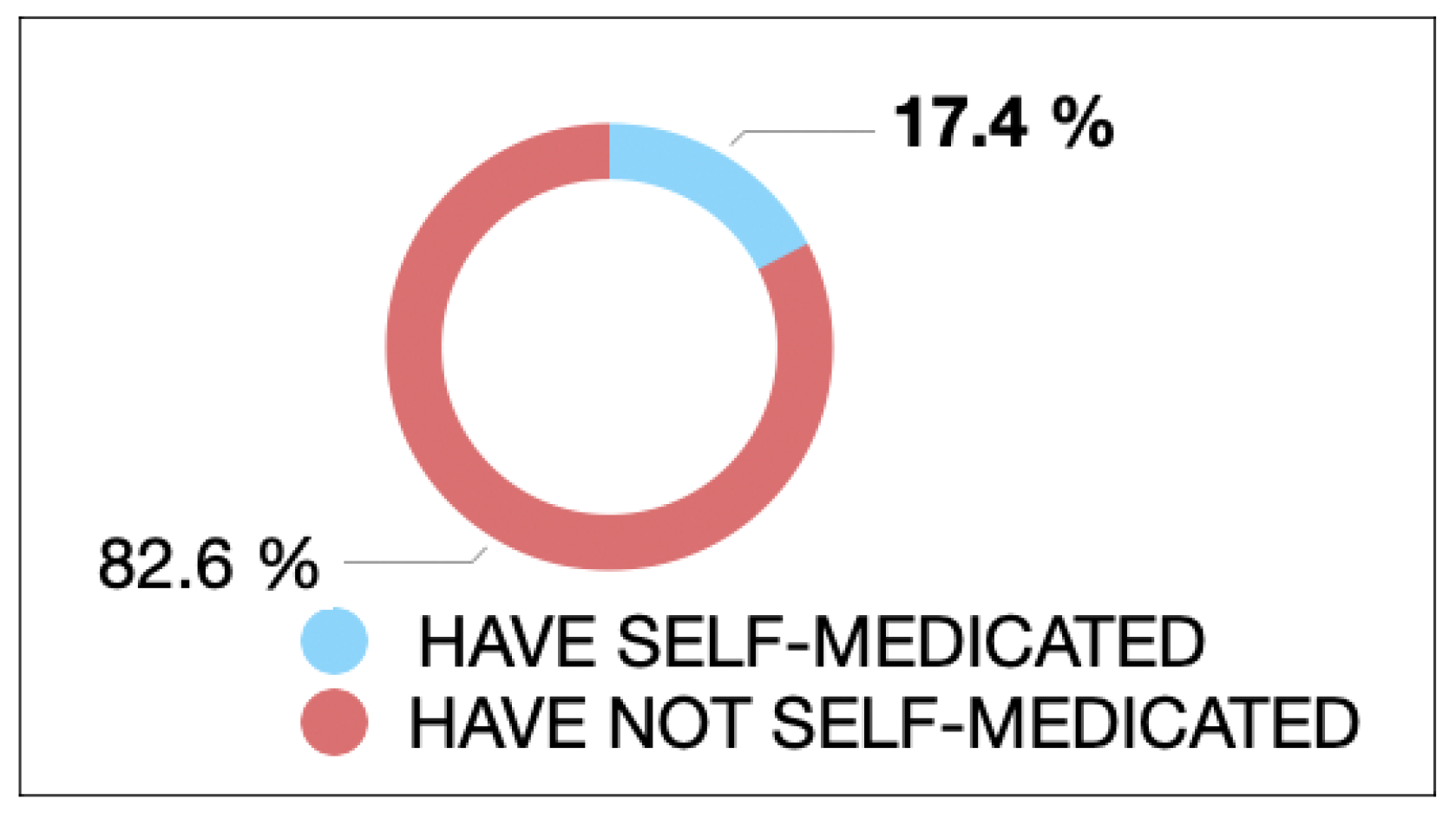

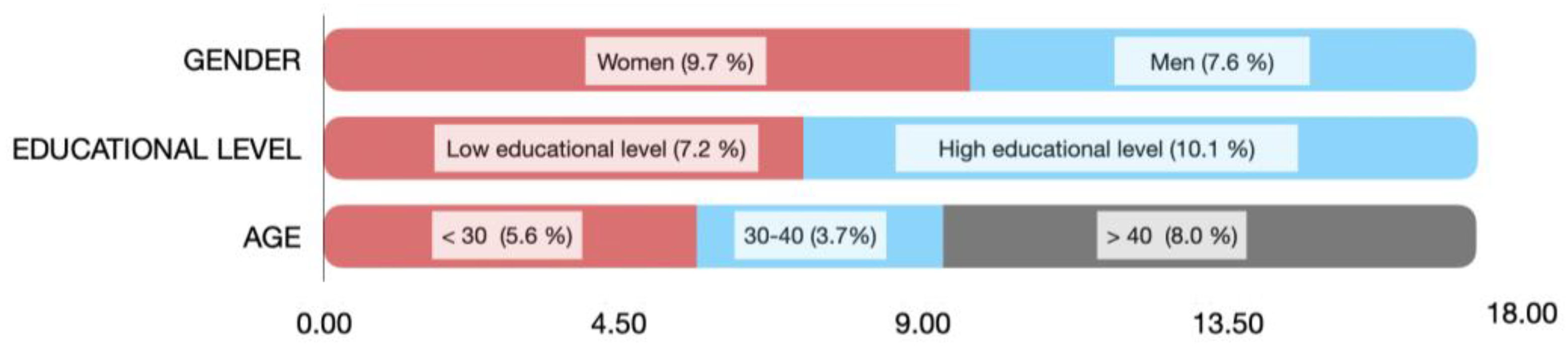

Regarding self-medication, 89 respondents (17.3 %) have even self-medicated on occasion with antibiotics without a prescription (

Figure 4). Women (9.7%) self-medicate more when faced with dental pain than men (7.6%), with non-significant differences (OR = 1.66; 95% CI = 1.04- 2.64; p < 0.05). People with a medium or low level of education self-medicated more than those with a high level of education, with significant differences (OR = 0.99; 95% CI = 0.99 - 2.52; p = 0.01). The majority of people who had ever self-medicated with antibiotics were over 40 years of age, with no significant differences (p > 0.05).

3.4. Benefits of antibiotic treatment.

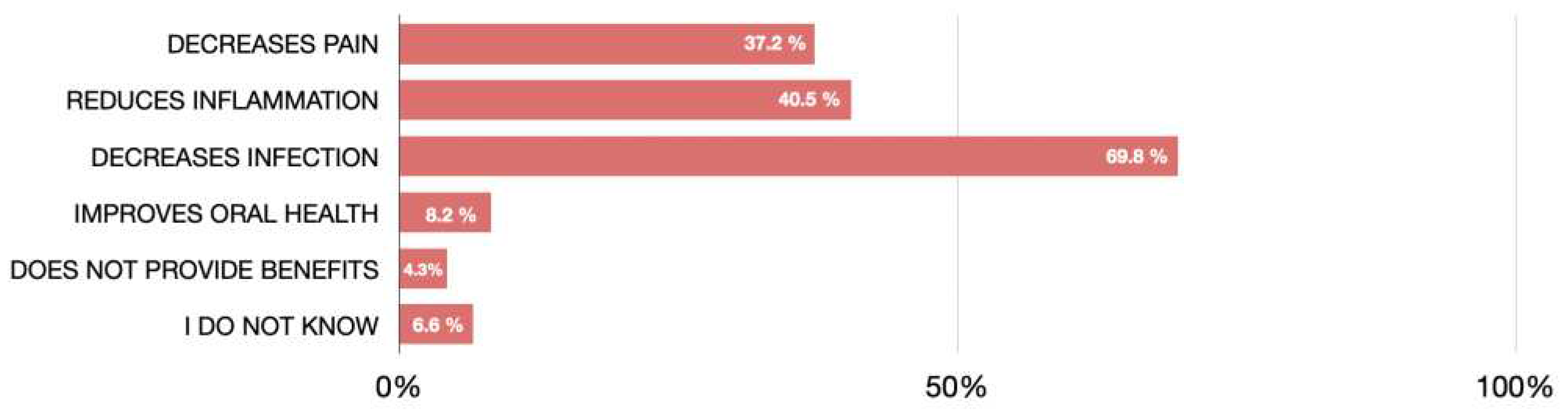

The respondents' beliefs about the potential benefits of antibiotic therapy are showed in

Figure 6. Reduction of infection (69.8 %) was the most selected benefit, followed by reduction of inflammation (40.5 %) and reduction of pain (37.2 %). There were no significant differences regarding sex, age and level of education (p > 0.05). With respect to age, it is observed that those over 40 consider that the use of antibiotics reduces the risk of infection (≤30 years 21.7% versus 30-40 years 17.0 % versus ≥40 years 61.3%; p=0.001).

3.5. Adverse effects of antibiotic treatment.

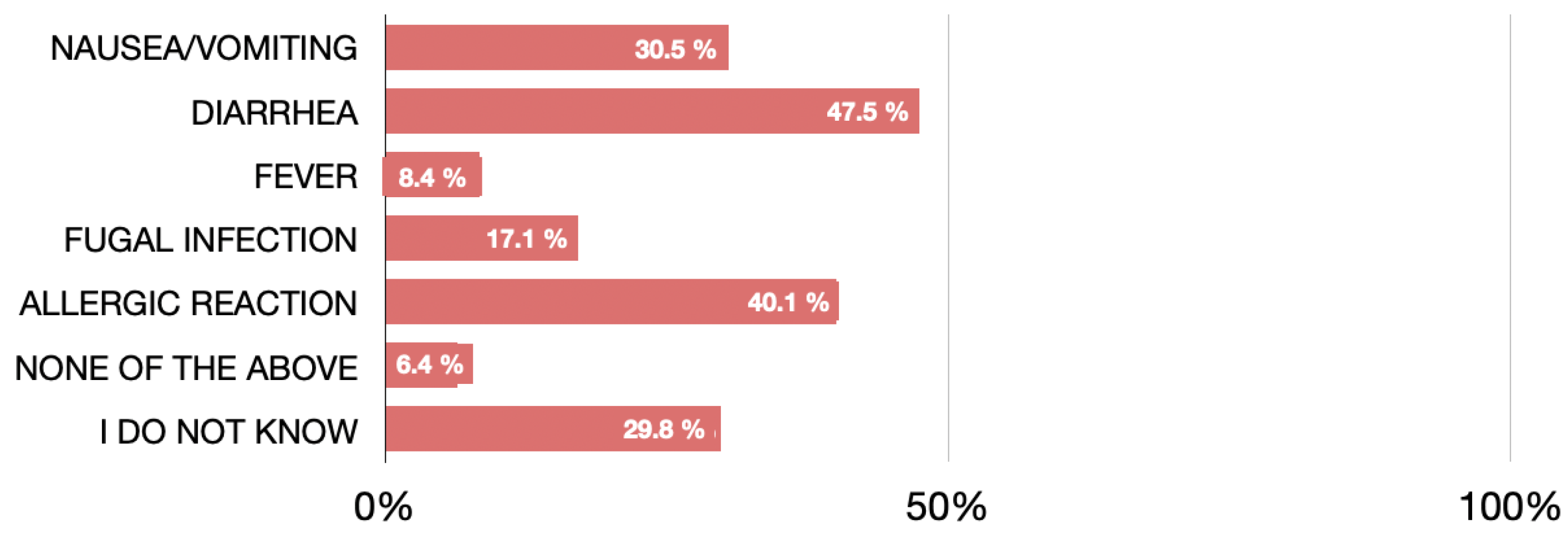

The answers to the question about the adverse effects of antibiotics are shown in the

Figure 8. Diarrhea (47.5%) was the adverse effect most cited by respondents, followed by allergic reaction (40.1%) and nausea/vomiting (30.5%).

Regarding gender, women are more likely to consider diarrhoea (p=0.001) and fungal infection (p=0.001) than men.

In terms of age, there is a greater polarity in the response, with those under 30 years of age and those over 40 years of age considering that antibiotics have the highest percentage of adverse effects due to fever (under 30 years of age), allergic reactions and nausea/vomiting (both age groups),

Finally, with respect to educational level, it was observed that participants with a higher level of education had a higher frequency of response for side effects in allergic reactions, fungal infections, diarrhoea and nausea/vomiting. (p < 0.05).

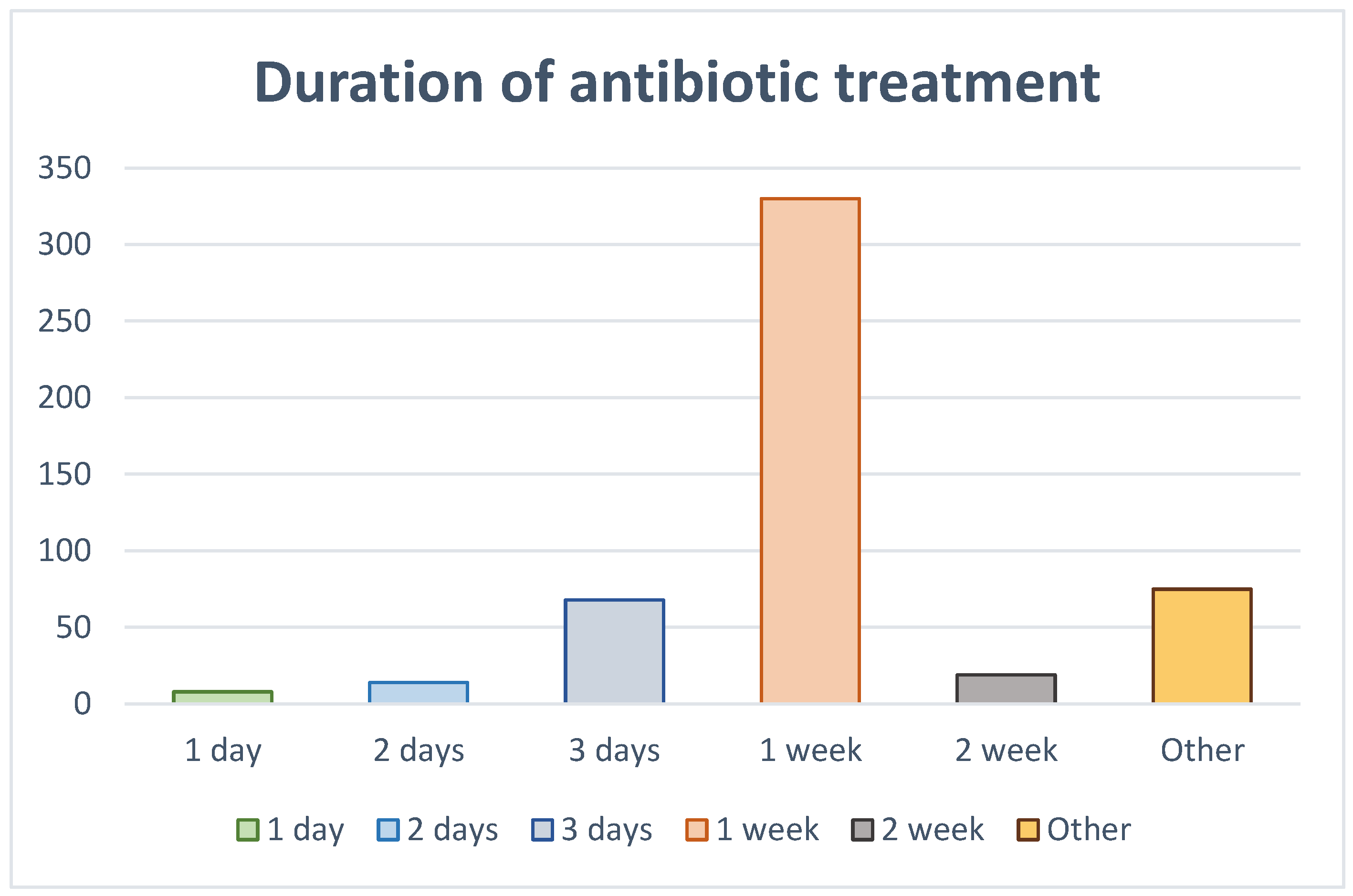

3.6. Duration of antibiotic treatment

When asked about the duration they believed antibiotic treatment should last, the majority of respondents (64.1%) considered that it should be one week, and 13.2% considered that it should be 3 days (Figure 9). In addition, in this case there were no significant differences in terms of sex, age and educational level (p > 0.05).

However, a difference by sex was observed, with women believing more strongly in extending the pattern by one week (Women 68,1% versus Men 56,6 %; p=0.06). With regard to age, the highest percentage of those over 40 years of age considered that they should extend their antibiotic regimen by at least one week (≤30 years 23% versus 30-40 years 16.1 % versus ≥40 years 60.9%; p=0.001).

3.7. knowledge of respondents regarding antibiotic resistance

Finally, respondents were asked about antibiotic resistance. Approximately half of those surveyed (274, 53.3%) responded that they were aware of the problem of antibiotic resistance caused by antibiotic overuse. In the answers to this question there were no significant differences in terms of sex, age and educational level (p > 0.05). However, the level of education did play a role in the knowledge of antibiotic resistance. The higher the level of education, the better the perception of the concept of antibiotic resistance (p=0.0001).

4. Discussion

The results of the present study, analyzing the responses to the survey by 514 people, demonstrates the lack of knowledge of the general population about the use of antibiotics in the treatment of endodontic infections, as well as the pressure exerted by patients on dentists.

As far as we know, this is the first study that reflects the current state of knowledge and perception of the general population on antibiotic resistance and the use and need for systemic antibiotics in the treatment of pulpo-periapical infections. Previous studies [

2,

10,

12]–[

15] have evaluated dentists' knowledge of antibiotic prescribing habits. However, although it is known that dentists' prescribing habits are sometimes influenced by patient pressure until now, no study had analyzed patients' knowledge and beliefs about antibiotic treatment in endodontics. Only a previous study had analyzed patients' beliefs about antibiotic treatment in cases of tooth extraction [

7].

The sample of this study was representative of the general population and the overall response rate was high (93.4%), larger than other studies [

7].

Several studies have investigated self-medication with antibiotics [

7,

16]–[

21] analyzing the impact of predisposing factors, such as knowledge and perception of antibiotic use, and facilitating factors (wealth of the country and health system factors). A survey carried out in 19 European countries showed that Spain, together with Lithuania and Romania, were countries with a very high rate of self-medication. Moreover, these three countries, together with Italy, were the countries where many antibiotics were accumulated at home [

18,

21] Antibiotic dispensing by tablet size can generate leftovers that contribute substantially to self-medication [

18]. In addition, medications may be left over due to patient noncompliance, as the patient may not take the prescribed amount of medication and subsequently self-medicate. It has been shown that 36 % of people who self-medicate do so using leftovers [

18,

21]. In Spain, antibiotics are not dispensed by exact number but by tablet size. In Spain, self-medication is a daily occurrence; a 2008 study showed that 18.1% of all Spaniards self-medicate [

5]. According to the results of the present study, 17.3% of respondents have self-medicated on occasion with antibiotics without a prescription. These results are similar to those previously described in Spain in 2008, in Portugal [

22] and in southern Europe [

18]. Regarding the relationship between self-medication and sex, women self-medicate more when faced with dental pain than men, although the difference was not significant (OR = 1.7;p > 0.05). The results of the present study agree with those of previous studies carried out in Spain and other countries [

5,

19,

20], who found that women had a greater exposure to the consumption of medication than men. On the contrary, they are not in accordance with the results of the study conducted in Portugal [

22], whose results showed a higher prevalence rate of self-medication in men. This difference could be explained by the different composition of the samples in both studies, with different proportions of men and women.

Concerning the educational level, although the percentage of self-medication is higher among people with a high level of education, the results of the present study do not show significant differences in self-medication in relation to educational level. Grigoryan et al. (2006) [

21] found similar results. It would be expected that patients' attitudes reflect their level of health literacy, which in turn may be related to education [

23].

Regarding age, the results of the present study have not found significant differences, and are not in agreement with the findings of previous studies where the highest prevalence of self-medication was found among younger ages. [

5,

21,

22].

However, the present results, showing that older patients with higher educational level had a more conservative perception of the need for antibiotic treatment, are in good agreement with those of Pérez-Amate et al. [

7].

The high percentage of patients who, if they do not receive antibiotics, would ask why or would go to a second doctor if the first one would not prescribe antibiotics, not only show the lack of knowledge of the population, but also demonstrate the degree of distrust towards health professionals and the social pressure to which professionals are subjected.

More than half of the participants think that antibiotics reduce pain and these results could be explained by the lack of updating of the health professional [

12,

13,

15,

24,

25] and the lack of time that the health professional sometimes dedicates to explaining to patients the need or not for antibiotic treatment. It is essential for the dentist to spend more time explaining to patients the reasons why they do not need antibiotics in each clinical situation [

7].

To determine the general population's knowledge of antibiotic use, different options of possible benefits of antibiotics were included in the survey, including: reduction of pain, reduction of inflammation, reduction of infection, improvement of oral health, no benefit and don't know. Reduction of infection (69.8 %) was the most selected benefit, in agreement with the results obtained in the previous study performed in Barcelona [

7].

According to clinical guidelines [

26], the duration of antibiotic treatment should be based on the improvement of the patient's symptoms, such that antibiotic therapy will last until symptoms have resolved. However, almost two third of the respondents considered that they were necessary for 1 week, without significant differences in relation to age, sex, or educational level. Only 13.2% considered the duration with antibiotics to be 3 days. Surveys previously conducted with patients did not analyze their perception regarding the duration of antibiotic treatment. The present results again highlight that the misconception that bacterial infections require "a full course" of antibiotic therapy still persists, but no evidence that a one-week period is necessary to treat endodontic infections has been found [

26].

Patients' erroneous knowledge regarding antibiotic treatment contributes to the misuse of antibiotics and, consequently, to the problem of the development of bacterial resistance. Even though there are currently many programs in place, both globally and internationally, to curb the increase in bacterial resistance, the results of the present study show that only approximately half of the patients (53%) are aware of the problem of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. In the study carried out in 2021 in Barcelona [

7], the patients' knowledge of antibiotic resistance was higher (69%). The present results showed that there was not significant differences in relation to age, sex, or educational level of respondents regarding knowledge of the problem of bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

This study is not without its limitations. On the one hand, cross-sectional descriptive studies cannot perform causality, they only describe a specific situation, thus undermining external validity. This situation has been overcome by increasing the sample size. On the other hand, despite the high internal consistency of the scale, it is necessary to validate scales that allow us to collect the behaviour of users in the use of antibiotics in the dental field.

Author Contributions

The authors declare: Conceptualization, J.M.-G., D.C.-B. and L.D.-D.; Methodology and Software, L.D.-D. and J.J.S.-E.; Validation, J.J.S.-E., J.M.-G., D.C.-B. and A.C.-F.; Formal Analysis, M.P.-C. and J.M.-G.; Investigation, L.D-D., A.C.-F., J.M.-G. and J.J.S.-E.; Data Curation, M.P-C., P.C.-B. and L.D.-D., Writing—Original Draft Preparation, L.D.-D. and J.M.-G.; Writing—Review and Editing, P.C.-B. and J.J.S.; Visualization, J.J.S.-M., D.C.-B., A.F.-C.; Supervision, M.P.-C. and J.M.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.