1. Introduction

Transfusion Dependent β-Thalassemia (TDT), is a congenital characterized by reduced or no production of hemoglobin, leading to chronic anemia and necessitating lifelong blood transfusions[

1]. During the last decades, TDT has gradually transformed from a life-threatening disorder into a chronic disease. The significant increase in survival rates has been attributed to the implementation of safe and systematic blood transfusions, the development of three effective iron chelators and the guided follow-up of patients in well-organized Thalassemia units. Nevertheless, the patients still confront the burden of the disease which affects their functional status and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL).

There is still an unmet need for a more comprehensive approach to assessing and managing health in Thalassemia, in accordance with the World Health Organization, which underlines that “health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease”. The term HRQoL describes aspects of life that are not generally considered as “health” and can be defined as “those aspects of self-perceived well-being that are related to or affected by the presence of disease or treatment”[

2]. Measuring HRQoL in Thalassemia offers a holistic approach to the burden of the disease and provides data for better communication between physicians, patients and their families[

3]. There is a growing research literature suggesting that psychological wellbeing may even be a protective factor in health, reducing the risk of chronic physical illness and promoting longevity[

4,

5]. In accordance, the assessment of HRQoL has become an essential endpoint in most clinical trials of continuously evolving treatments or interventions[

6,

7,

8,

9]. In countries with large populations of TDT patients, including Greece, evaluating the status of HRQoL may contribute to determining and improving social and healthcare policies.

HRQoL can be assessed with Quality of Life (QoL) questionnaires completed by the patients themselves, constituting a common type of Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) [

10]. Globally, very few reports have efficiently focused on the HRQoL of adult Thalassemia patients and the vast majority have used the generic SF-36 questionnaire [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. A generic questionnaire can be very useful for comparing the results with the general population, but cannot be as sensitive as a disease-specific questionnaire in terms of revealing differences in QoL between patient subgroups or between different interventions. In 2014, Klaassen et al designed the TranQol, a disease-specific QoL questionnaire for TDT patients[

16]. The hypothesized conceptual framework for this new measure was to capture the full scope of HRQoL in TDT patients, including the domains of social, emotional, and physical well-being[

17]. The translated versions of TranQol, including the Greek translation, are continuously utilized in several international clinical trials in Thalassemia, including the recently published phase 3 BELIEVE trial of Luspatercept[

18]. Nevertheless, there are limited real-world published data on the implementation of TranQol outside the context of a clinical trial.

In Greece, there is also insufficient evidence regarding disease-specific QoL in representative samples of the TDT patient population. In 2012, Lyrakos et al developed and evaluated the psychometric properties of the Specific Thalassemia Quality of Life Instrument (STQOLI) to assess HRQoL in TDT patients[

19]. Nevertheless, the questionnaire was not utilized in subsequent QoL studies, neither in Greece nor in other countries. In all other studies of Greek TDT patients, only generic questionnaires were employed in small groups of patients and the assessment involved limited domains of HRQoL, including mental health and satisfaction with iron chelation therapy [

12,

20]. In 2017, the Greek version of TranQol was successfully validated, providing the potential for a comprehensive and disease-specific assessment of HRQoL in TDT patients[

21].

The primary endpoint of this study was to assess the HRQoL in a representative Greek TDT patient population, using the combination of the generic SF-36v2 and the disease-specific TranQol questionnaire. The secondary endpoint was to examine differences in HRQoL between prespecified subgroups of patients and identify possible determinants of HRQoL. We hypothesized that sociodemographic and clinical factors affect HRQoL of TDT patients in Greece. This is the first study of HRQoL in a representative population of TDT patients in Greece. Our results could offer a baseline reference of HRQoL for ongoing and future clinical trials in TDT patients, reveal more vulnerable TDT patient subgroups, and contribute to a better understanding of the impact of the disease and available interventions on HRQoL.

2. Materials and Methods

Τhis was a cross-sectional multicenter study in a population of adult TDT patients that took place from October to December 2017. All patients were systematically transfused and closely monitored at four well-organized Thalassemia units in Greece. The study sites were all located in urban areas of Greece and involved the adult Thalassemia Unit of the Second Department of Internal Medicine, Aristotle University, Hippokration General Hospital of Thessaloniki, the Thalassemia Unit of AHEPA General Hospital of Thessaloniki, the Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Disease Unit of the General Hospital of Larissa and the Thalassemia Unit of the University Hospital of Patras. To reflect real life and avoid selection bias, all TDT patients from each Thalassemia Unit were invited consecutively and according to predefined and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Briefly, the participants were aged 18 years and older, had a confirmed diagnosis of transfusion-dependent Thalassemia, and had efficient reading and writing skills without significant intellectual or sensory disorders. The patients that were participating in a clinical trial, were pregnant or had been recently hospitalized were excluded, on the grounds of avoiding factors that could cause any transient change in the participants’ QoL. During their routine transfusion visit, the participants were asked to complete two quality-of-life questionnaires; the generic Greek SF-36v2[

22], which measures the Physical and Mental QoL domains and was used for comparisons with the general population’s QoL, and the validated Greek version of the disease-specific TranQol[

21], which is more sensitive in revealing differences between patient subgroups and involves the assessment of overall QoL and five QoL subdomains; Physical Health (PH), Emotional Health (EH), Sexual Health (SH), Family Functioning (FF) and School and Career Functioning (SCF). Higher scores of both questionnaires indicate better QoL (0 indicates worse possible health state and 100 best health state). The TranQol and SF-36 were considered complete if ≥ 75% and ≥ 50% of the questionnaire items were answered, respectively[

16,

23]. We prespecified patient subgroups that might have different QoL according to clinical, demographic and socioeconomic status. Thus, we looked for differences between age groups, gender, family structures, educational backgrounds, working status, comorbidities, types of iron chelation therapy and hemosiderosis status. The MRI T

2* examination was used to assess iron overload status and define patients with no heart or no hepatic iron overload (Heart T

2* >20msec and liver iron concentration (LIC)

3mg Fe/g dry weight, respectively)[

1,

24]. All data were retrieved from the patients’ medical records and the variables collected are listed in

Table 1. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

2.1. Statistics

Qualitative and quantitative variables were analyzed descriptively, with qualitative data presented as frequencies and quantitative data as mean ± standard deviation (SD). TranQol scores were calculated from a mathematical equation provided by the developers[

16] and the SF-36 scores were calculated from the QualityMetric Health Outcomes

TM Scoring Software 4.5[

25]. We used the “½ SD method”, a distribution-based approach that has been developed to define clinically meaningful differences in each QoL questionnaire score [

26]. Any differences of 0.5 x SD on previously published TranQol and SF-36v2 scores were considered clinically significant [

21]. Univariate linear regression analysis was performed to assess the association between independent variables (age, gender, working status, educational status, marital status, offsprings, Heart and Liver MRI T

2* status, co-morbidities, type of chelation therapy) and TranQol summary and subdomains scores. A less-restrictive α-level of 0.2 was used in univariate linear regression analysis to identify a broad range of factors that would be retained as candidate variables in the next step of multivariate analysis. Stepwise regression was conducted to select the most parsimonious models of independent explanatory factors that may be associated with overall and subdomain QoL status, after adjusting for confounding factors. To identify a broader range of independent factors, a less restrictive alpha level of 0.1 was employed, indicating statistical trends for values where 0.05<P<0.10. The multivariate analysis data were checked and met the assumptions of homogeneity of variance and linearity, and the residuals were approximately normally distributed. For each of the significant predictors, we estimated the regression coefficients (B) and their 95% confidence intervals. The data were analysed using IBM SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

2.2. Sample size

The study population sample size was determined by the study’s primary aim, which was to evaluate HRQol in the Greek TDT patient population. A representative sample was estimated to be 242 patients for the total 2099 TDT population in Greece[

27] with 90% confidence interval and 5% margin of error[

28]. The total study population was set to be at least 403 patients, taking into account a 40% nonresponse rate and a minimum 60% Response Rate (RR), respectively (definition proposed by the American Association of Public Opinion Research, AAPOR RR6) [

29,

30]. We set the power to 0.8 (80%) and a 5% significance level to have a high probability of detecting a Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) between patient subgroups, in terms of the secondary endpoint of the study. The minimal sample size was estimated to be 64 patients for each subgroup[

28]. A Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) in SF-36v2 and TranQol scores was defined according to Norman et al.[

26], who suggested that the value of half a standard deviation (0.5xSD) of baseline scores can serve as a default value for important patient-perceived change on QoL measures used with patients with chronic diseases. In this study, the MCID was calculated from the half a standard deviation (0.5xSD) of previously published SF-36v2 and TranQol scores, in a survey of 94 Greek TDT patients (

Table 2) [

21].

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

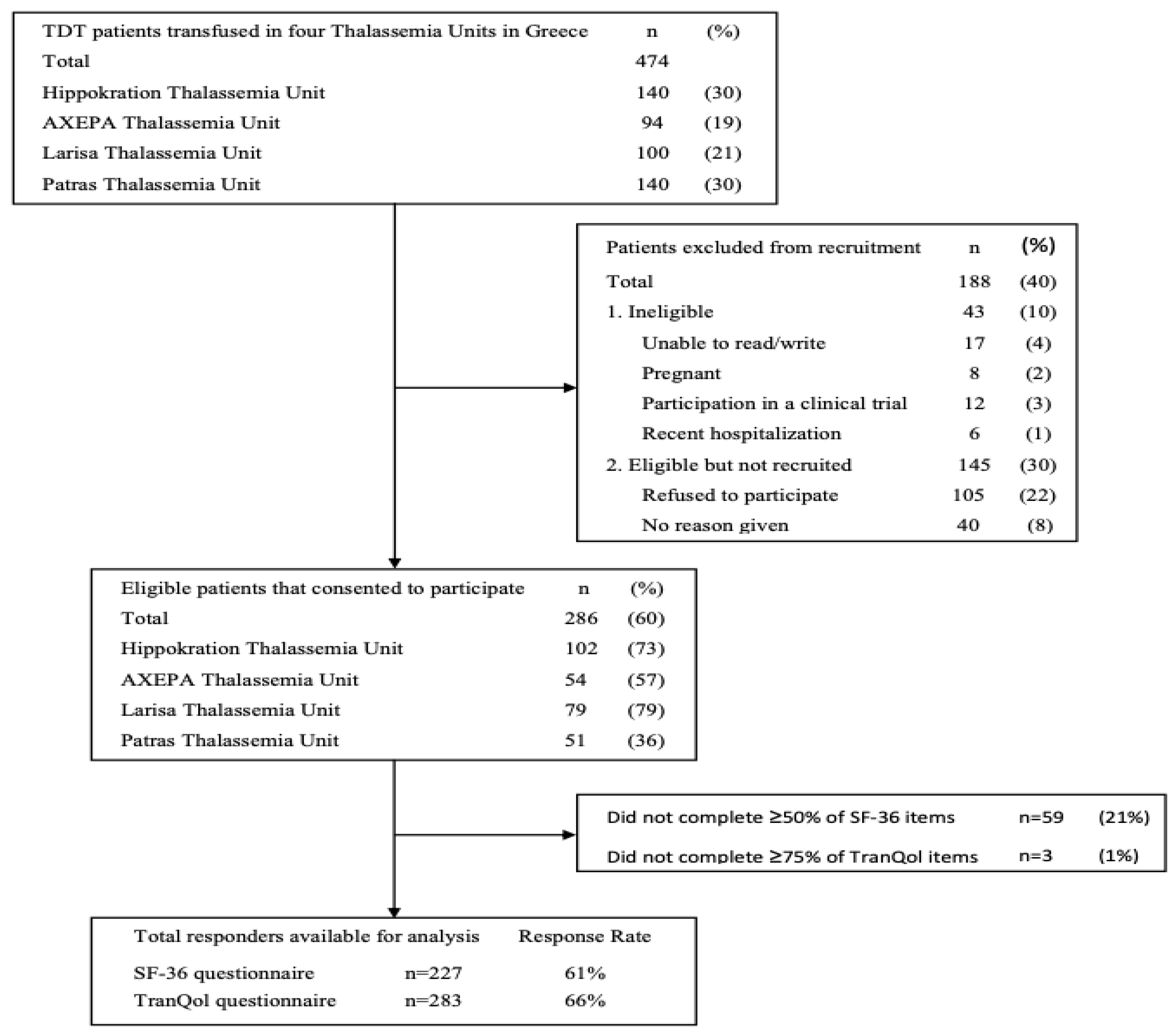

A total of 474 adult TDT patients were screened from four Thalassemia Units of which 286 (60%) met eligibility criteria and consented to participate in the study. The primary reason for exclusion was patient refusal, accounting for 22% of those screened. Additionally, 10% of patients were excluded for not meeting the study's inclusion/exclusion criteria, whereas no reason was recorded for the remaining 8% of patients who were not recruited. The response rates of the patients who completed the SF-36v2 (≥50% items) and the TranQol (≥75% items) questionnaires were 61% (n=227) and 66% (n=283), respectively (

Figure 1 Flow diagram). The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in

Table 1. The participants’ mean±SD age was 39±9 years (range:18-68) and 58% were female. Almost half of the study population were married (46%) and had offsprings (42%). Most participants had a higher educational level (77%) and 59% were employed. Among the participants with a history of co-morbidity (68%) the most frequent disorder was osteoporosis (39%). Regarding chelation therapy, Deferasirox monotherapy (35%) or the combination of Deferoxamine/Deferiprone (39%) were the two most frequently used iron chelating regimens. Only 7% of the participants had an abnormal Heart MRI T

2*, whereas 39% of the participants had an abnormal Liver MRI T

2*.

3.2. Health-related Quality of Life in Transfusion-Dependent Thalassemia patients

The TranQol and SF-36 summary and subdomain scores in the study population are reported in

Table 2. The overall mean±SD TranQol summary score was 71±14% and the overall mean±SD of SF-36v2 PCS and MCS scores were 51±8% and 49±9%, respectively. In the same table, we report the SF-36v2 and TranQol MCID values that represent a threshold for meaningful changes in each questionnaire’s score. In

Figure 2, we present the comparison of HRQoL between TDT patients and the general population. The SF-36 subdomain scores from our survey of TDT patients were substantially lower compared to the only available data of SF-36 scores in the general Greek population, published in 2005[

22], and the differences were clinically important (>MCID). On the other hand, the TranQol scores from our survey were higher compared to national surveys in the United Kingdom[

31], Canada[

16] and in Peshawar of Pakistan[

32], and the differences in TranQol summary and most subdomain scores were clinically important (

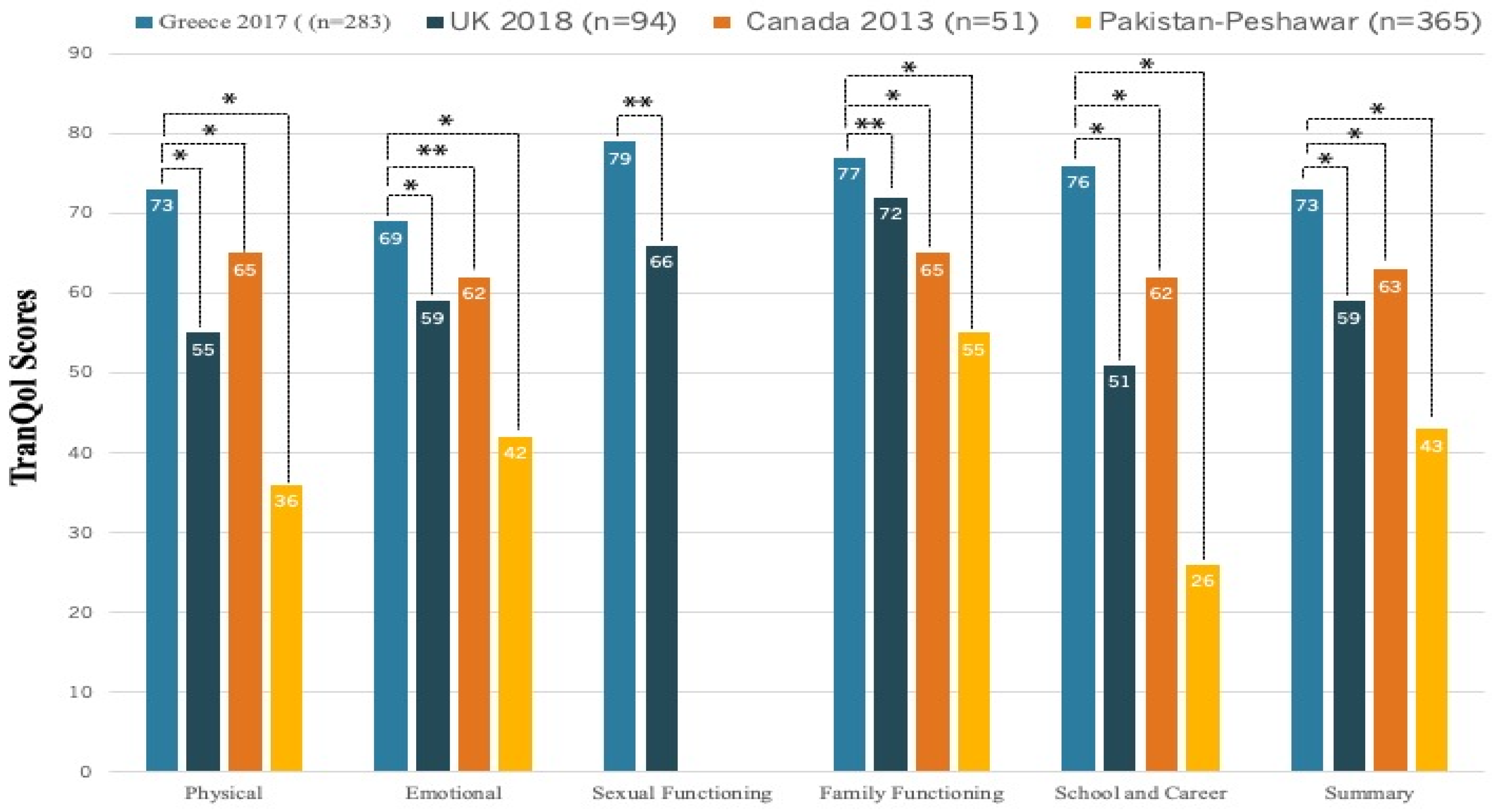

Figure 3).

3.3. Factors that influence Health-related Quality of Life among TDT patients

In terms of statistical trends, the factors that were associated with Summary TranQol scores in univariate regression analysis included Age (B=-0.3, 95% CI -0.5,-0.2), Marriage (B=-3.2, 95% CI -6.5,0.2), Employment (B=7.5, 95% CI 4.2,10.7), Higher Education (B=4.2, 95% CI 0.4,7.9), Comorbidities (B=-5.1, 95% CI -8.6,1.6), Iron Chelation with Deferasirox compared to Deferoxamine monotherapy (B=4.1, 95% CI -0.4,8.5) and Abnormal Liver MRI T2* (B=3.2, 95% CI -0.3,6.7) (

Table 3). Abnormal Heart MRI T2* (B=-2.6, 95% CI -8.4,3.3) was negatively associated only with the physical subdomain. Female gender exhibited a significant association with higher scores in Family Functioning (B=4.5, 95% CI 0.2,8.6) and School and Career (B=7.2, 95% CI 1.9,12.5) subdomains. In multivariate regression analysis (

Table 4), age, female gender, employment and iron chelation with Deferasirox compared to Deferoxamine monotherapy were the independent factors that significantly influenced HRQoL, after adjusting for confounding factors. Based on the multivariate model, there was on average a decrease of 0.3 units in TranQol summary scores for every 1-year increase in age (B=-0.3, 95%CI 0.5,-0.02), corresponding to a 20-year increase in age for a TranQol MCID of 6 units (Clinically Important Increase in age=6/0.3). Employment was associated with a significant average increase in TranQol Summary, Physical, Emotional, and Family Functioning scores and the levels of increase were greater than the MCID reported in

Table 2, reflecting clinically meaningful changes. Female gender was associated with a significant increase in the TranQol Family Functioning (B=7.4, 95% 1.5,13.4) and School and Career (B=10.8, 95% 3.3,18.2) subdomain scores, and the change was clinically important (B>MCID,

Table 2). Deferasirox compared to Deferoxamine monotherapy was only associated with an average increase in the TranQol Physical subdomain score (B=5.8, 95%CI 0.01,11.6), and the change was marginally clinically important (MCID=6,

Table 2).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first QoL survey in a representative sample of the TDT population in Greece, implementing the combination of the generic SF-36v2 and the Thalassemia-Specific TranQol questionnaires.

We found that the HRQoL status in TDT patients is lower than in the general Greek population. The difference was clinically important in both Physical and Mental health domains, which implies that although there is a significant development in the clinical management and treatment of TDT patients, the optimization of QoL needs to be improved (

Figure 2). Our findings are in accordance with the existing literature, which suggests that TDT has a significantly negative effect on physical and mental health status [

11,

13,

32,

33,

34,

35].

The relatively high TranQol scores in Greece reflect the good level of HRQoL for TDT patients (

Figure 3). The TranQol summary score in our survey was 73%, a clinically important higher score compared to the TranQol summary score of 54% in a recently published Global Longitudinal Study of HRQoL in adult TDT patients (preliminary results) in the U.S.A, United Kingdom, France, Italy and Germany [

36]. The Summary and TranQol subdomain scores in our study were also marginally higher compared to the TranQol results from the phase 3 BELIEVE trial of luspatercept in 15 countries (Australia and countries across Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, North America, and Southeast Asia), yet these differences were not clinically important[

18]. The relatively high TranQol scores in Greece could be attributed to the established special infrastructure, involving well-organized medical centers, access to medical resources and availability of blood units and iron chelators, in combination with social, educational and professional benefits. The same social and healthcare environment may not be offered in all countries, as healthcare policies and services are heterogeneous for these patients [

37]. The striking difference in HRQoL between Greece and Pakistan (TranQol Summary: 73%vs43%,

Figure 3) addresses the need to promote health equity in Thalassemia across the world, especially in the era of novel drugs and new therapeutic strategies.

After controlling for possible confounding sociodemographic and clinical variables, as shown in the multivariate analysis in

Table 3, we found that older age and unemployment were the two most significant factors that were associated with lower HRQoL. The absence of higher education, comorbidities and iron chelation with Deferoxamine monotherapy were additional factors that negatively affected certain subdomains of HRQoL.

Our results are in alignment with previous studies reporting that in TDT age is independently associated with reduced QoL[

14,

15,

31,

38], although, in the general population, most researchers agree that older adults show social and emotional functioning that is equal to or superior to younger adults[

4,

39]. Sobota et al, compared the HRQoL in TDT with the US norms and showed that HRQoL is lower in older TDT patients than would be expected in the general population[

15]. The effect of age on HRQoL in TDT patients should be interpreted with caution, considering that older TDT patients may have grown up in worse healthcare environments, lacking the availability of oral iron chelators and no access to the present improved Thalassemia infrastructure. On the other hand, TDT is a chronic disease and may have a cumulative negative effect on HRQoL, similar to other persons with disabilities[

40]. A close follow-up of the younger TDT patients may elucidate the effect of age on HRQoL.

Employed TDT patients exhibited both significantly and clinically higher TranQol Summary and Subdomain scores (Physical Health, Emotional Health, and Family Functioning). Most studies show that there is a positive relationship between employment and the HRQoL of persons with disabilities[

40]. To date, there is limited published data regarding the effect of employment on HRQoL in TDT. Most studies have implemented generic QoL questionnaires, that may not have been as sensitive as TranQol in detecting the effect of employment on HRQoL. A recent survey in Saudi Arabia was one of the few studies reporting that TDT participants holding professional jobs had better mental HRQoL scores compared to those working in clerical or manual jobs[

41]. It should also be noted that the employment rates for TDT patients are different among countries. In our study population, 59% of patients were employed, in a study in the Middle East the employment rate was 54%[

42], whereas in the aforementioned Global Survey in the U.S.A, United Kingdom, France, Italy and Germany (preliminary data) only 34% TDT patients were employed [

36]. Our findings underline the importance of the established employment policy for TDT patients in Greece, which offers job opportunities for working in the public sector and a potential for earlier retirement with a fully paid pension. Nevertheless, providing an accessible and suitable working environment for TDT patients remains a challenge for policymakers, considering that a recent study by Shah et al showed that the mean working productivity impairment for TDT patients was 42% versus a typical working week[

31].

Gender and choice of iron chelator were significantly associated only with certain domains of HRQoL. In

Table 4, we showed that Female patients exhibited significantly higher TranQol scores of Family Functioning and School and Career subdomains. There is no consensus in the literature about the effect of gender on HRQoL in TDT. Sobota et al reported that in the USA female patients had worse HRQoL[

15], whereas Ansari et al exhibited that female patients had a better quality of life in Iran[

43]. It could be speculated that the differences in the cultural and social environment of each country may explain the contradictory effect of gender on HRQoL.

Regarding the comparisons between different iron chelators, Deferasirox was positively associated only with the subdomain of Physical health and only in comparison with Deferoxamine monotherapy, whereas there was no difference in HRQoL compared to patients treated with Deferoxamine combined with oral Deferiprone. The published data regarding the effect of iron chelators on HRQoL are heterogeneous in the literature. Sobota et al in a study with one of the largest cohorts of TDT patients, concluded that the type of chelator was not associated with HRQoL and commented that this might be because usually, patients are free to choose their chelation[

15]. Goulas et al in a study of quality of life and iron chelation treatment satisfaction showed that TDT patients receiving Deferoxamine, alone or in combination with an oral iron chelator, perceived higher treatment efficacy, comparable HRQoL and comparable satisfaction with iron chelator than patients receiving only oral iron chelator with Deferasirox[

12]. In clinical practice, physicians may use our findings to inform patients about the choice of iron chelator and answer any concerns about their impact on everyday life.

This study had some limitations. The cross-sectional design of the study may be less informative in detecting differences in HRQoL between patient subgroups compared to a longitudinal prospective design. All participants were recruited from reference Thalassemia centres in urban areas of Greece, so our results may not reflect HRQoL in TDT patients living in the province area and treated in less organized Thalassemia Units. Nevertheless, the study had a high participation rate, a high probability of detecting significant differences between almost all patient subgroups (power=0.8, significance level=5%) and represented real-world clinical practice, since it was conducted in a routine care environment.

The assessment of HRQoL status among TDT patients in Greece has been an unmet need until today. In this multicentre study, we have managed to measure HRQoL using the combination of the generic SF-36v2 and the disease-specific TranQol questionnaires, with an adequate response rate from the participants in a representative sample of the Greek TDT population. We have exhibited that both social-demographic and clinical factors may have an impact on HRQoL of TDT patients. The implementation of the disease-specific TranQol offers the perspective for a future reevaluation of HRQoL and the potential to identify emerging factors that may have an impact on HRQoL in the era of novel treatments and interventions in TDT.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of TranQol, an international disease-specific QoL questionnaire, allowed us to quantify the HRQoL of TDT patients in Greece, define a baseline point for future follow-up, compare TranQol scores between Greece and other countries and identify more vulnerable patient subgroups, such as unemployed and older patients. Overall, the HRQoL status in TDT is relatively high in Greece, possibly due to the healthcare environment and social support. Other countries with high incidence rates of TDT may adopt the “paradigm of Greece” and improve the HRQoL of TDT patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K.; methodology, P.K., M.M., I.P.; software, V.L., D.A., R.K; validation, P.K., I.P., M.M.; formal analysis, P.K.; investigation, P.K.; resources, P.K., I.C., S.K., D.P., M.D., A.K., V.L.; data curation, I.P., M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.; writing—review and editing, P.K., N.R., M.M., I.P., D.P., M.D., A.K.; visualization, P.K.; supervision, A.T., E.V.; project administration, P.K., D.P., S.K., M.D., A.K., V.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hippokration General Hospital of Thessaloniki, Greece (213/4-5-2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Taher, A. T., K. M. Musallam and M. D. Cappellini. "Beta-thalassemias." N Engl J Med 384 (2021): 727-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33626255. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, S. "Clinical and public health perspectives and applications of health-related quality of life measurement." Soc Sci Med 41 (1995): 1383-94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8560306. [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L. S., R. S. Huckman and N. W. Wagle. "Making patients and doctors happier - the potential of patient-reported outcomes." N Engl J Med 377 (2017): 1309-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28976860. [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A., A. Deaton and A. A. Stone. "Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing." The Lancet 385 (2015): 640-48. 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61489-0. [CrossRef]

- Trachtenberg, F. L., E. Gerstenberger, Y. Xu, L. Mednick, A. Sobota, H. Ware, A. A. Thompson, E. J. Neufeld and R. Yamashita. "Relationship among chelator adherence, change in chelators, and quality of life in thalassemia." Quality of Life Research 23 (2014): 2277-88. 10.1007/s11136-014-0671-2. [CrossRef]

- Basch, E. "Patient-reported outcomes - harnessing patients' voices to improve clinical care." N Engl J Med 376 (2017): 105-08. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28076708. [CrossRef]

- Gebski, V., A. Obermair and M. Janda. "Toward incorporating health-related quality of life as coprimary end points in clinical trials: Time to achieve clinical important differences and qol profiles." J Clin Oncol 40 (2022): 2378-88. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35576502. [CrossRef]

- Miguel, R. S., A. M. Lopez-Gonzalez, E. Sanchez-Iriso, J. Mar and J. M. Cabases. "Measuring health-related quality of life in drug clinical trials: Is it given due importance?" Pharm World Sci 30 (2008): 154-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17721699. [CrossRef]

- Chassany, O., P. Sagnier, P. Marquis, S. Fullerton and N. Aaronson. "Patient-reported outcomes: The example of health-related quality of life--a european guidance document for the improved integration of health-related quality of life assessment in the drug regulatory process." Drug Information Journal 36 (2002): 209-38. [CrossRef]

- Higgins JPT, T. J., Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019,.

- Rodigari, F., G. Brugnera and R. Colombatti. "Health-related quality of life in hemoglobinopathies: A systematic review from a global perspective." Front Pediatr 10 (2022): 886674. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36090573. [CrossRef]

- Goulas, V., A. Kouraklis-Symeonidis, K. Manousou, V. Lazaris, G. Pairas, P. Katsaouni, E. Verigou, V. Labropoulou, V. Pesli, P. Kaiafas, et al. "A multicenter cross-sectional study of the quality of life and iron chelation treatment satisfaction of patients with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia, in routine care settings in western greece." Qual Life Res 30 (2021): 467-77. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32920766. [CrossRef]

- Arian, M., M. Mirmohammadkhani, R. Ghorbani and M. Soleimani. "Health-related quality of life (hrqol) in beta-thalassemia major (beta-tm) patients assessed by 36-item short form health survey (sf-36): A meta-analysis." Qual Life Res 28 (2019): 321-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30194626. [CrossRef]

- Amid, A., R. Leroux, M. Merelles-Pulcini, S. Yassobi, A. N. Saliba, R. Ward, M. Karimi, A. T. Taher, R. J. Klaassen and M. Kirby-Allen. "Factors impacting quality of life in thalassemia patients; results from the intercontinenthal collaborative study." Blood 128 (2016): 3633-33. 10.1182/blood.V128.22.3633.3633. [CrossRef]

- Sobota, A., R. Yamashita, Y. Xu, F. Trachtenberg, P. Kohlbry, D. A. Kleinert, P. J. Giardina, J. L. Kwiatkowski, D. Foote, V. Thayalasuthan, et al. "Quality of life in thalassemia: A comparison of sf-36 results from the thalassemia longitudinal cohort to reported literature and the us norms." Am J Hematol 86 (2011): 92-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21061309. [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, R. J., N. Barrowman, M. Merelles-Pulcini, E. P. Vichinsky, N. Sweeters, M. Kirby-Allen, E. J. Neufeld, J. L. Kwiatkowski, J. Wu, L. Vickars, et al. "Validation and reliability of a disease-specific quality of life measure (the tranqol) in adults and children with thalassaemia major." Br J Haematol 164 (2014): 431-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24180641. [CrossRef]

- Robert J Klaassen, S. A., Melanie Kirby Allen, Katherine Moreau, Manuela Merelles Pulcini, Melissa Forgie, Victor Blanchette, Rena Buckstein,, Isaac Odame, Ian Quirt, , Karen Yee, , Durhane Wong Rieger , Nancy L Young. "Introducing the tran qol: A new disease-specific quality of life measure for children and adults with thalassemia major." Blood Disorders Transf 4 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, M. D., A. T. Taher, A. Piga, F. Shah, E. Voskaridou, V. Viprakasit, J. B. Porter, O. Hermine, E. J. Neufeld, A. A. Thompson, et al. "Health-related quality of life in patients with β-thalassemia: Data from the phase 3 <scp>believe</scp> trial of luspatercept." Eur J Haematol (2023): 10.1111/ejh.13975. [CrossRef]

- Lyrakos, G. N., D. Vini, H. Aslani and M. Drosou-Servou. "Psychometric properties of the specific thalassemia quality of life instrument for adults." Patient Prefer Adherence 6 (2012): 477-97. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22848151. [CrossRef]

- Vlachaki, E., N. Neokleous, D. Paspali, E. Vetsiou, E. Onoufriadis, N. Sousos, S. Hissan, S. Vakalopoulou, V. Garypidou and P. Boura. "Evaluation of mental health and physical pain in patients with beta-thalassemia major in northern greece." Hemoglobin 39 (2015): 169-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25976778. [CrossRef]

- Klonizakis, P., R. Klaassen, N. Sousos, A. Liakos, A. Tsapas and E. Vlachaki. "Evaluation of the greek tranqol: A novel questionnaire for measuring quality of life in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients." Ann Hematol 96 (2017): 1937-44. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28884221. [CrossRef]

- Pappa, E., N. Kontodimopoulos and D. Niakas. "Validating and norming of the greek sf-36 health survey." Qual Life Res 14 (2005): 1433-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16047519.

- Maruish, M. E. User's manual for the sf-36v2 health survey. Quality Metric Incorporated, 2011,.

- Kattamis, A., Y. Aydinok and A. Taher. "Optimising management of deferasirox therapy for patients with transfusion-dependent thalassaemia and lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes." Eur J Haematol 101 (2018): 272-82. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29904950. [CrossRef]

- "Short-form health survey 36 version 2." https://www.qualitymetric.com/health-surveys/the-sf-36v2-health-survey/.

- Norman, G. R., J. A. Sloan and K. W. Wyrwich. "Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation." Med Care 41 (2003): 582-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12719681. [CrossRef]

- Voskaridou, E., A. Kattamis, C. Fragodimitri, A. Kourakli, P. Chalkia, M. Diamantidis, E. Vlachaki, M. Drosou, S. Lafioniatis, K. Maragkos, et al. "National registry of hemoglobinopathies in greece: Updated demographics, current trends in affected births, and causes of mortality." Ann Hematol 98 (2019): 55-66. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30196444. [CrossRef]

- Walters, S. J. Qulatiy of life outcomes in clinical trials and health-care evaluation: A practical guide to analysis and interpretation. John Wiley & Sons. Ltd, 2009,.

- 2016.

- Bennett, C., S. Khangura, J. C. Brehaut, I. D. Graham, D. Moher, B. K. Potter and J. M. Grimshaw. "Reporting guidelines for survey research: An analysis of published guidance and reporting practices." PLoS Med 8 (2010): e1001069. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21829330. [CrossRef]

- Shah, F., P. Telfer, M. Velangi, S. Pancham, R. Wynn, S. Pollard, E. Chalmers, J. Kell, A. M. Carter, J. Hickey, et al. "Routine management, healthcare resource use and patient and carer-reported outcomes of patients with transfusion-dependent β-thalassaemia in the united kingdom: A mixed methods observational study." eJHaem 2 (2021): 738-49. [CrossRef]

- Yasar, Y., R. Asfandyar, K. Naseem, S. Inayat, K. Saba and T. Abid. "Quality of life and its determinants in transfusion dependent thalassemia." Pak J Physiol 14 (2018): -.

- Cappellini, M. D., A. Kattamis, V. Viprakasit, P. Sutcharitchan, J. Pariseau, A. Laadem, V. Jessent-Ciaravino and A. Taher. "Quality of life in patients with beta-thalassemia: A prospective study of transfusion-dependent and non-transfusion-dependent patients in greece, italy, lebanon, and thailand." Am J Hematol 94 (2019): E261-E64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31321793. [CrossRef]

- Floris, F., F. Comitini, G. Leoni, P. Moi, M. Morittu, V. Orecchia, M. Perra, M. P. Pilia, A. Zappu, M. R. Casini, et al. "Quality of life in sardinian patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia: A cross-sectional study." Qual Life Res 27 (2018): 2533-39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29922915. [CrossRef]

- Bazi, A., O. Sargazi-Aval, A. Safa and E. Miri-Moghaddam. "Health-related quality of life and associated factors among thalassemia major patients, southeast of iran." J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 39 (2017): 513-17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28859037. [CrossRef]

- Nanxin Li, J. D., Adriana Boateng-Kuffour, Melanie Calvert, Laurice Levine, Neelam Dongha, Zahra Pakbaz, Filkret Kaan Oran, Kamran Iqbal, Farrukh Shah, Antony P. Martin. "Health-related quality of life and disease impacts in adults with transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia: Preliminary results from the longitudinal survey." Blood 140 (2022): 10869-70. [CrossRef]

- Bellis, G., & Parant, A. "Beta-thalassemia in mediterranean countries. Findings and outlook." Investigaciones Geográficas, (2022): 129-38. [CrossRef]

- Panepinto, J. A. "Health-related quality of life in patients with hemoglobinopathies." Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012 (2012): 284-9. 10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.284. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23233593.

- Charles, S. T. and L. L. Carstensen. "Social and emotional aging." Annu Rev Psychol 61 (2010): 383-409. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19575618. [CrossRef]

- Ra, Y.-A. and W. H. Kim. "Impact of employment and age on quality of life of individuals with disabilities." Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 59 (2016): 112-20. [CrossRef]

- Adam, S. "Quality of life outcomes in thalassaemia patients in saudi arabia: A cross-sectional study." East Mediterr Health J 25 (2019): 887-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32003447. [CrossRef]

- Bou-Fakhredin, R., N. N. Ghanem, F. Kreidieh, R. Tabbikha, H. Daadaa, J. Ajouz, S. Koussa and A. T. Taher. "A report on the education, employment and marital status of thalassemia patients from a tertiary care center in the middle east." Hemoglobin 44 (2020): 278-83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32727228. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S., A. Baghersalimi, A. Azarkeivan, M. Nojomi and A. Hassanzadeh Rad. "Quality of life in patients with thalassemia major." Iran J Ped Hematol Oncol 4 (2014): 57-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25002926.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).