1. Introduction

In recent years, social-emotional competencies have gained recognition in global education as vital indicators for assessing students' development and the quality of teaching [

1]. These competencies encompass essential skills related to self-adaptation and social development that children acquire and apply [

2]. They constitute a critical facet of students' non-cognitive development [

3], significantly impacting their academic progress and future success [

4]. Research indicates that fostering social-emotional competence positively influences student achievement while mitigating negative behaviors and emotional distress [

5,

6]. Moreover, cultivating social-emotional competence during adolescence aids students in navigating future employment competition [

7]. Studies have highlighted that individuals' career paths and success in the job market are significantly influenced by their social-emotional competence [

8]. Hence, it becomes imperative to understand effective methods to enhance students' social-emotional skills.

Distributed leadership, characterized by collaborative decision-making and coordinated action, has garnered attention in 21st-century education for bolstering school organizational capacity and supporting teacher growth [

9,

10]. Previous studies have demonstrated that distributed leadership elevates teacher job satisfaction and encourages professional collaboration [

11], resulting in enhanced teacher self-efficacy [

12]. Furthermore, it contributes to the quality of teachers' instructional methods and their adeptness in implementing teaching innovations [

13,

14].

Research also suggests that distributed leadership positively impacts teachers' trust, motivation, organizational commitment, and self-efficacy [

15,

16,

17]. This not only influences their instructional practices but also their social and emotional competencies. However, it remains unclear whether distributed leadership significantly contributes to students' social and emotional competence. Additionally, existing research indicates that the influence of school leadership on student development is typically indirect [

18]. Numerous researchers have extensively explored the correlation between school leadership and student academic achievement [

19,

20], leading to two prevailing conclusions: Firstly, school leadership significantly influences student achievement. Secondly, the empirical association between school leadership and student achievement predominantly operates indirectly, mediated by various teacher and school-related factors [

18,

21].

Although previous studies have shown positive associations between distributed leadership and teacher self-efficacy [

12], as well as student-centered instructional practices [

13], there is limited understanding of whether and how these factors mediate the relationship between distributed leadership and students' social-emotional competence.

This study utilizes data from the 2021 OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills (SSES) for Chinese adolescents. Its aim is to investigate how distributed leadership fosters adolescents' social and emotional competence while elucidating the roles of student-centered instructional practices and teacher self-efficacy. The ultimate goal is to offer guidance and insights into enhancing adolescents' social and emotional skills.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social and Emotional Competence

The theoretical foundations of social and emotional competence trace back to earlier research exploring emotional intelligence, characterized by three primary frameworks: the Salovey & Mayer model [

22], the Bar-On model [

23], and the Goleman model [

24]. These frameworks emphasize self-awareness, self-regulation, empathy, communication, and social interaction, significantly influencing subsequent definitions and assessment tools for social and emotional competence [

25].

Among various assessment tools, two prominent frameworks are notably significant: the CASEL framework developed by the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) and the Big Five framework, a collaborative effort by the same organization. CASEL defines social-emotional learning (SEL) as the capacity of individuals to acquire and adeptly apply skills in understanding and managing emotions, setting and achieving positive goals, expressing empathy, cultivating positive relationships, and making responsible decisions [

26]. According to this framework, social and emotional competence comprises five interlinked dimensions: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relational skills, and responsible decision-making. The CASEL framework is extensively referenced in SEL interventions and literature reviews [

5].

Emerging research proposes an alternative definition of social and emotional competence within the Big Five framework [

27]. This model encompasses Extraversion, Affinity, Dutifulness, Neuroticism, and Openness, offering a comprehensive descriptive categorization that consolidates various social and emotional competencies into a cohesive structure [

28]. Utilizing the Big Five personality model as an overarching structure for social-emotional competencies facilitates the development of comprehensive and practical assessments that encompass a wide range of variables, pertinent to scholars and policymakers.

The SSES database established by OECD also adopts the Big Five personality model, dividing social and emotional competencies into five dimensions encompassing 15 sub-competencies. These include responsibility, perseverance, self-control, stress resistance, optimism, emotional control, empathy, cooperation, trust, tolerance, curiosity, creativity, gregariousness, resoluteness, and the ability to collaborate. Notably, compared to the CASEL framework, the Big Five framework provides a more nuanced delineation of competencies and is better suited for extensive cross-sectional surveys [

27]. Consequently, this study addresses research inquiries based on the dimensions constructed by the OECD.

2.2. Distributed Leadership and Social and Emotional Competence

Distributed leadership, initially proposed by Cecil Gibb in the Handbook of Social Psychology, gained traction after the nineties through continual development [

29]. Various perspectives have shaped the conceptualization of distributed leadership, including situational learning [

30], systems [

31], process [

32], and behavioral [

33] viewpoints. Notably, the perspectives of Spillane and others hold considerable recognition among scholars. According to this theoretical perspective, distributed leadership constitutes the interaction among the leader, subordinates, and the situation, forming the foundation of leadership practice [

34]. In this study, it specifically refers to an empowerment and shared responsibility management model within schools, authorizing teachers to engage in decision-making, fostering a favorable school climate [

35]. Under this leadership model, teachers actively cultivate both individual and collective responsibility to address the diverse learning needs of their students [

10].

Distributed leadership practices contribute significantly to fostering a supportive school culture, fostering positive student-teacher interactions, and nurturing robust student-teacher relationships—crucial components of adolescents' social and emotional competence [

36]. Moreover, implementing distributed leadership in instructional management positively influences students' perceptions of teacher care, closely linked to empathy, self-awareness, and social awareness [

37]. Additionally, distributed leadership correlates positively with individual creativity [

38]. This analysis forms the basis for Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1: Distributed leadership significantly enhances adolescents' social and emotional competence.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Student-centered Teaching Practices

Student-centered instructional practices, rooted in constructivism, advocate for learners actively constructing knowledge rather than passively receiving it [

39]. These practices encompass diverse methods like problem-based learning, project-based learning, cooperative group learning, and inquiry-based learning [

40]. Emphasizing student responsibility for their learning needs, this approach places the teacher in the role of a facilitator or organizer. Teachers within this framework must employ varied teaching methods flexibly to address diverse student needs, fostering continual improvement in students' creativity, perseverance, organizational, interpersonal, and collaborative skills. Studies highlight that student-centered practices yield higher student scores compared to traditional methods, contributing significantly to students' knowledge, skills, and qualities [

41,

42]. Specifically, they positively predict the use of deep learning methods and enhanced self-reported competencies, encompassing cognitive and practical skills, even in larger class settings [

43].

Effective leadership styles and robust school support are vital for teachers to develop instructional skills emphasizing the significance of student-centered approaches. Distributed leadership, esteemed for its empowered and shared leadership concept, correlates positively with several school organizational factors influencing teacher-centered instructional practices, encompassing organizational change, teacher leadership, professional learning communities, teacher self-efficacy, and school climate [

44]. Additionally, distributed leadership indirectly impacts teacher instructional practices through teacher collaboration and job satisfaction, where student-centered instructional practices constitute one of the sub-dimensions [

13]. This analysis forms the basis for Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2a: Distributed leadership significantly influences student-centered instructional practices.

Hypothesis 2b: Student-centered instructional practices significantly impact students' social and emotional competence.

Hypothesis 2c: Student-centered instructional practices mediate the impact of distributed leadership on adolescents' social and emotional competence.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Teacher Self-Efficacy

Teacher self-efficacy embodies teachers' beliefs in their ability to influence student learning outcomes, such as student interest and motivation, through their teaching activities [

45]. It reflects teachers' confidence in their teaching abilities. Empirical studies indicate a positive correlation between teacher self-efficacy and students' perceived teacher emotional support [

46], closely tied to adolescents' social and emotional competence. Moreover, teacher efficacy significantly influences students' perceived social relationships, enhancing their interpersonal skills and social awareness [

47].

In various educational settings where teachers possess ample time for targeted instruction based on their discretion, teacher-led leadership models are prevalent [

48]. Distributed leadership amplifies teacher self-efficacy through three primary channels [

49]. Firstly, by empowering teachers through distributed leadership practices, it cultivates a positive school climate that encourages knowledge sharing and collaborative efforts among teachers, thereby enhancing instruction [

44]. Secondly, granting teachers greater control over their work environment motivates them to invest more in instruction preparation, implementation, and reflection [

50]. Thirdly, verbal encouragement and support from leaders play a pivotal role in boosting teachers' self-efficacy [

51]. Facilitating effective communication between administrators and teachers is essential in achieving shared goals.

Furthermore, several studies have established that teacher self-efficacy mediates the effects of distributed leadership on teacher-related aspects. For instance, it mediates the impact of distributed leadership on teachers' job well-being, professional well-being [

49], and indirectly influences students' reading literacy [

52]. Nonetheless, it remains unclear whether teacher self-efficacy also mediates the effects of distributed leadership on students' social and emotional competence. Hence, based on this literature review, Hypothesis 3 is proposed:

Hypothesis 3a: Distributed leadership significantly impacts teacher self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 3b: Teacher self-efficacy significantly influences adolescents' social and emotional competence.

Hypothesis 3c: Teacher self-efficacy mediates the impact of distributed leadership on adolescents' social and emotional competence.

2.5. Student-Centered Teaching Practices and Teacher Self-Efficacy

A quasi-experimental study revealed the efficacy of project-based learning (PBL) in enhancing teacher self-efficacy [

53]. It found that positive student responses to instructional practices could potentially mediate the relationship between PBL and teacher self-efficacy. Similarly, Holzberger et al. [

54] conducted a longitudinal follow-up survey, illustrating that instructional practices significantly predicted teachers' self-efficacy. Moreover, analyses using TALIS 2018 data confirmed the positive influence of instructional practices on teachers' self-efficacy, a trend observed across diverse cultural contexts, including Chinese, Canadian, Finnish, Japanese, and Singaporean settings [

55].

In light of the literature analysis, this study posits Hypothesis 4:

Hypothesis 4a: Student-centered instructional practices positively impact teacher self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 4b: Student-centered instructional practices and teacher self-efficacy collectively mediate the effects of distributed leadership on adolescents' social and emotional competence.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Participants

This study utilized Chinese data from the 2019 OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) Study on Social and Emotional Skills (SSES) among adolescents. The survey employed stratified sampling to gather data from primary and secondary school students, parents, teachers, and schools within the districts and counties under Suzhou City's jurisdiction in China. It specifically focused on assessing adolescents' social and emotional competence and examining the potential factors contributed by teachers, parents, and schools affecting this competence. Given the study's emphasis on teacher variables impacting students' social and emotional competence and the potential influence of social desirability bias on self-report measures, multiple sources of data were collected [

56]. This included self-reports from students, reports from teachers, and reports from parents regarding adolescents' social-emotional competence, ensuring data triangulation for improved accuracy. Data matching was conducted across the three groups—students, teachers, and parents—based on unique identifiers (student ID, teacher ID, and parent ID) within the survey data to facilitate subsequent data analysis. The adolescent sample for this study consisted of 7,246 individuals, comprising 3,409 girls (47.05%), 3,824 boys (52.77%), and 13 (0.18%) with unspecified gender.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Distributed Leadership

The measurement of this variable was conducted using the teachers' questionnaire, where they were asked to rate the statement "This school provides opportunities for staff to actively participate in school decision-making" on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2.2. Student-centered Teaching Practices

Student-centered instructional practices were evaluated using six questions. For instance, "Group discussions among students" was rated based on frequency (1: almost never to 4: almost every class), achieving a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.909. Factor analysis confirmed the validity, showing standardized factor loadings between 0.685 and 0.865 for each question.

3.2.3. Teacher Self-efficacy

Teacher self-efficacy was evaluated using seven questions, such as "Convincing students that they can do their homework well," which was assessed based on frequency (1: not at all to 4: a lot). The assessment achieved a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.935. Validated factor analyses demonstrated standardized factor loadings between 0.768 and 0.871 for each question.

3.2.4. Social and Emotional Competence

Drawing from the Big Five Model, the SSES evaluates this competency across five dimensions, each comprising three sub-competencies. These dimensions include Task Competency (Responsibility, Perseverance, Self-Control), Emotional Regulation Competency (Resistance to Stress, Optimism, Emotional Control), Collaboration Competency (Empathy, Cooperation, Trust), Openness (Inclusiveness, Curiosity, Creativity), and Interaction Competency (Agreeableness, Boldness, Vigor).

In this study, adolescents' self-assessed social and emotional competence, teacher-assessed social and emotional competence, and parent-assessed social and emotional competence were selected as dependent variables for analysis. Each subscale of the adolescents' self-assessed and parent-rated social and emotional competence scales consisted of eight questions, measured on a scale of agreement (1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree). Meanwhile, each subscale of the teacher-evaluated social and emotional competence scale contained three questions, measured on a similar agreement scale.

The mean scores of the 15 sub-competencies were used to determine the adolescents' social and emotional competence. Higher scores denoted greater social and emotional competence. These scores provided the final assessment for adolescents' self-assessed, teacher-assessed, and parent-assessed social and emotional competence. The reliability of the assessments from adolescents, teachers, and parents regarding social and emotional competence has been thoroughly tested, yielding favorable overall results [

57].

3.3. Data Analysis

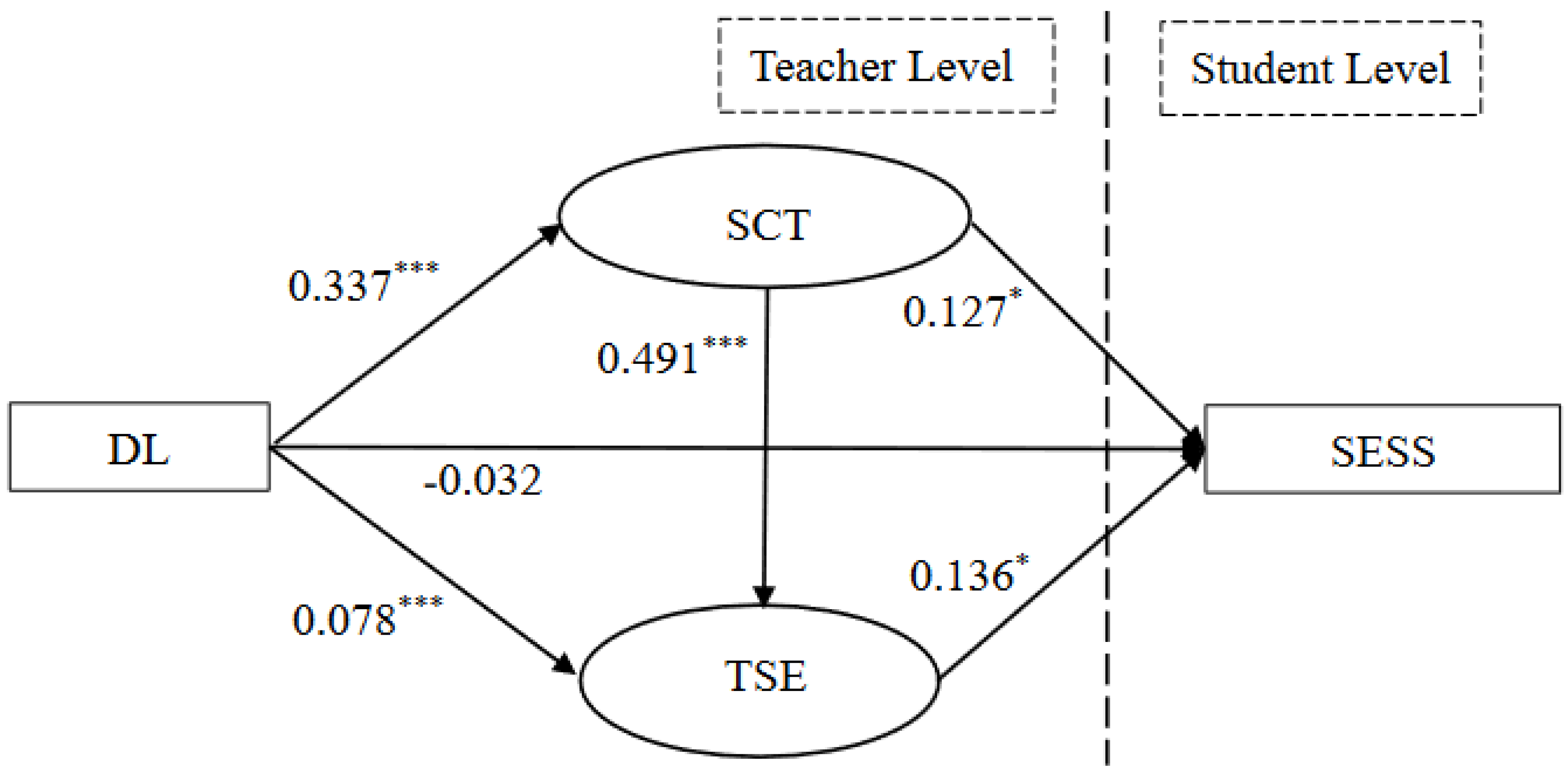

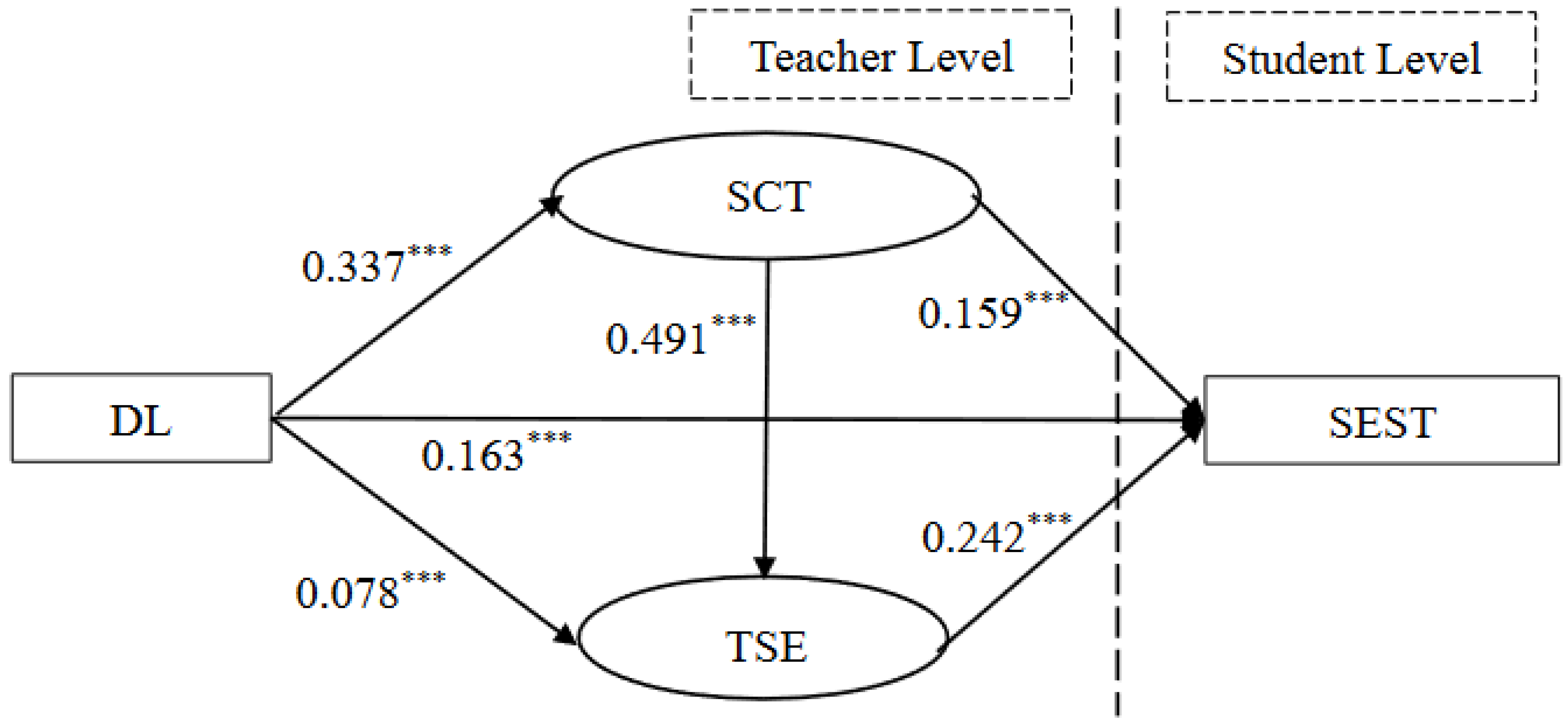

Due to the hierarchical structure of the data encompassing teachers, parents, and adolescents (e.g.,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), where Distributed Leadership, Student-Centered Instructional Practices, and Teacher Self-Efficacy represent teacher-level variables, and Adolescent Social and Emotional Competence pertains to student-level variables with multiple students nested within different teachers, this study employed Mplus 8.3 analysis software and Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling (MSEM) for data analysis. The analytical process comprised several steps:

Step 1: The Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was utilized to gauge between-group variation, determining the suitability of Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling for data analysis. The ICC theoretically ranges from 0 to 1. An ICC value exceeding 0.059 indicates substantial between-group variation, warranting multilevel analysis [

58].

Step 2: Descriptive statistics were employed to present comprehensive scores for distributed leadership, student-centered instructional practices, teacher self-efficacy, and adolescents' social and emotional competence. Furthermore, this step assessed potential correlations among these variables.

Step 3: Construction of Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Intra-group Correlation Coefficients

To compute the intra-group correlation coefficient, this study initially developed the null model. Findings revealed the ICC values of adolescents' self-assessment for social and emotional competence at 0.060, teachers' assessment at 0.419, and parents' assessment at 0.013. It is evident that data analysis utilizing multilevel methods is necessary when using adolescents' self-assessment and teacher-assessment of social and emotional competence as dependent variables. Conversely, the ICC values based on parent ratings were low, rendering them unsuitable for multilevel analysis. Consequently, the subsequent analysis incorporated only the results derived from adolescents' self-assessment and teachers' assessment.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics presented in

Table 1 indicate high scores for distributed leadership, student-centered instructional practices, teacher self-efficacy, as well as adolescents' self-assessed and teacher-assessed social and emotional competence. The correlation analysis revealed a notable positive association among the variables, except for distributed leadership, which did not exhibit a significant correlation with adolescents' self-assessed social and emotional competence.

4.3. Results of Structural Equation Modelling

Multilevel structural equation modeling was performed with adolescents' self-assessed social and emotional competence as the dependent variable. The model fit indices were X2 =1444.250, df=86; CFI=0.943; TLI=0.931; RMSEA=0.048; SRMR=0.040 (Optimal values: CFI>0.9; TLI>0.9; RMSEA<0.06; SRMR<0.08). Similarly, another model was constructed using the social and emotional competence of teacher evaluation as the dependent variable, yielding X2 =1463.155, df=86; CFI=0.943; TLI=0.931; RMSEA=0.048; SRMR=0.040. Both models demonstrated a good fit, establishing the credibility of the results.

The standardized path coefficient test results depicted in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 indicate that distributed leadership does not directly influence adolescents' self-rated social and emotional competence. However, it significantly predicts teacher-rated social and emotional competence (β = 0.163,

p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 1 partially.

Distributed leadership positively predicts student-centered teaching practices (β = 0.337, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 2a. Furthermore, student-centered instructional practices exhibit a significant positive effect on both student self-assessed social and emotional competence (β = 0.127, p < 0.05) and teacher-rated social and emotional competence (β = 0.159, p < 0.001), thus confirming Hypothesis 2b.

Regarding distributed leadership, it positively predicts teacher self-efficacy (β = 0.078, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 3a. Additionally, teacher self-efficacy significantly influences adolescents' self-rated social and emotional competence (β = 0.136, p < 0.05) and teacher-rated social and emotional competence (β = 0.242, p < 0.01), confirming Hypothesis 3b.

Moreover, student-centered teaching practices significantly impact teacher self-efficacy (β = 0.491, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis

The mediation effect test results among variables are presented in

Table 2. Notably, student-centered instructional practices significantly mediate the influence of distributed leadership on both adolescents' self-assessed social and emotional competence (β = 0.043,

p < 0.05) and teacher-rated social and emotional competence (β = 0.053,

p < 0.001), confirming hypothesis 2c.

Teacher self-efficacy similarly mediates the impact of distributed leadership on adolescents' self-rated social and emotional competence (β = 0.011, p < 0.05) and teacher-rated social and emotional competence (β = 0.019, p < 0.001), thus confirming hypothesis 3c.

Moreover, the combined effect of Student-Centered Instructional Practices and Teacher Self-Efficacy acts as a chain mediator, influencing the relationship between distributed leadership and both adolescents' self-assessed social and emotional competence (β = 0.022, p < 0.05) and teacher-rated social and emotional competence (β = 0.040, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 4b.

Regarding the impact of distributed leadership, the total indirect effect on adolescents' self-rated social and emotional competence was significant (β = 0.076, p < 0.001). However, the direct effect was not significant, indicating complete mediation. Similarly, for teacher-rated social and emotional competence, the total indirect effect of distributed leadership was significant (β = 0.112, p < 0.001), with a significant direct effect. Notably, the proportion of the indirect effect in the total effect was calculated as 40.73% (0.112 / (0.163 + 0.112)).

5. Discussion

5.1. The Direct Impact of Distributed Leadership on Social and Emotional Competence

The study revealed that distributed leadership positively influences teachers' evaluations of social and emotional competence. This leadership approach, emphasizing school empowerment and shared responsibilities among teachers, fosters an environment conducive to decision-making, ultimately benefiting student development [

59]. The implementation of distributed leadership reflects a supportive school climate, encouraging positive social interactions between students and teachers. Consequently, adolescents learn crucial social and emotional skills like cooperation, empathy, helpfulness, trust, and tolerance.

However, the study also noted that distributed leadership does not significantly impact adolescents' self-rated social and emotional competencies. This finding could be attributed to the presence of two mediating variables: student-centered instructional practices and teacher self-efficacy. These mediators create an indirect effect, allowing distributed leadership to influence adolescents' self-rated social and emotional competence through other pathways, rather than directly affecting it. Previous research has highlighted the indirect relationship between school leadership and student success, often affected by organizational factors like teachers' values, beliefs, dispositions, behaviors, as well as the school's culture and environment [

60].

5.2. The Mediating Role of Student-Centered Teaching Practices

The study revealed that distributed leadership can influence adolescents' social and emotional competence through its impact on student-centered instructional practices. By providing teachers with greater autonomy and encouraging innovative teaching methods such as cooperative group learning and project-based learning, distributed leadership enhances students' critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, collaboration, and interpersonal skills. Various studies, including those by Bryk and Camburn, have demonstrated the positive impact of distributed leadership on improving teaching quality and student engagement [

61,

62]. Additionally, Shields' research highlighted its role in aiding teachers' decision-making and facilitating smooth instructional activities [

63]. These studies collectively support the notion that implementing distributed leadership can foster innovative teaching approaches, enhance teaching quality, and contribute to the holistic development of adolescents.

In June 2019, the State Council emphasized the significance of contextualized teaching and project-based learning in enhancing the quality of compulsory education. Adolescents' social and emotional competence encompasses multiple dimensions, where authentic problem scenarios serve as ideal contexts to assess and promote skills like creativity, emotional regulation, authentic problem-solving, and collaboration. However, implementing these student-centered instructional practices depends on the autonomy and decision-making authority granted to teachers by distributed leadership. Consequently, distributed leadership plays a crucial role in encouraging diverse models of student-centered instructional practices, ultimately enhancing students' social and emotional competence. Aligning with existing research and educational policies, these findings underscore the indirect yet positive predictive influence of distributed leadership on adolescents' social and emotional competence by shaping student-centered instructional practices.

5.3. The Mediating Role of Teacher Self-Efficacy

The findings illustrate that teacher self-efficacy serves as a mediator not only between distributed leadership and students' self-assessed social and emotional competence but also between distributed leadership and teachers' evaluated social and emotional competence. Essentially, distributed leadership indirectly shapes adolescents' social and emotional competence through its impact on teachers' self-efficacy. As an emerging model in school management, distributed leadership empowers teachers with decision-making authority, fostering a positive environment that stimulates their motivation, enhances their self-efficacy, and fosters a sense of belonging. Operating within this leadership model encourages teachers to continuously improve their teaching competence, thereby promoting adolescents' social and emotional development.

Muijs' study identified a positive correlation between distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy, and teacher engagement [

64]. It emphasized that implementing distributed leadership signals support, trust, and affirmation to teachers, nurturing their role identity and enhancing their self-efficacy [

65]. Increased involvement in school decision-making processes also contributes to teachers' confidence, self-esteem, and belief in their ability to positively impact the overall development of young individuals. Proponents of distributed leadership stress its potential to establish supportive school environments where teachers collectively take responsibility to cater to diverse student learning needs [

66].

5.4. Chain Mediation of Student-Centered Teaching Practices and Teacher Self-Efficacy

The study found that distributed leadership indirectly influences adolescents' social and emotional competence through student-centered instructional practices and teacher self-efficacy. There is a potential association among distributed leadership, student-centered instructional practices, teacher self-efficacy, and adolescents' social and emotional competence, as highlighted in the literature analysis. This study further delineates the mechanisms between these variables, elucidates the combined effect of distributed leadership on adolescents' social and emotional competence, and presents a new avenue for influencing it.

In line with social exchange theory, which explores reciprocity norms within organizations, there are concepts of both direct and indirect reciprocity [

67]. Direct reciprocity involves mutual help where the recipient returns the favor to the giver. Indirect reciprocity encompasses a third party, often within the organization, creating a complex pattern of social interaction. In this study, employing the principle of indirect reciprocity, the school supported teachers by implementing distributed leadership, benefiting both the teachers and the organization. Empowering teachers and promoting teamwork and leadership cultivated teachers' autonomy, resulting in improvements in curriculum content and diverse student-centered teaching approaches.

As a consequence, teachers empowered students by adopting varied student-centered practices, encouraging student initiative within the classroom. Through this process, teachers developed deeper classroom insights, increased confidence in teaching, and enhanced their self-efficacy, reaping direct benefits from the implemented strategies. Ultimately, students, as third-party beneficiaries, received valuable feedback from both the school and teachers, contributing to the well-rounded development of their social and emotional competence.

6. Implications

Firstly, empowering teachers and facilitating shared decision-making are pivotal in implementing distributed leadership. Centralizing power in the school principal's hands can lead to drawbacks, making empowerment and sharing of responsibilities critical to the principal's success [

68]. School decision-making is intricate, often spanning various subjects, reflecting specialization's complexity. Principals, unable to possess all expertise, depend on teachers from diverse disciplines to collaborate, necessitating the delegation of leadership authority. Simultaneously, nurturing teachers' leadership abilities is vital. Teachers need decision-making prowess to underpin informed school choices. Hence, regular training is essential to enhance teachers' decision-making skills.

Secondly, effective social and emotional competence cultivation should be integrated into daily classroom teaching. Encouraging student-centered learning environments through group cooperative, problem-oriented, and project-based approaches empowers students in the classroom. Teachers should promote group activities, fostering adolescents' responsibility, empathy, cooperation, trust, communication, and problem-solving skills. Guiding students actively, offering feedback, trusting their capabilities, nurturing divergent thinking, and encouraging innovation contribute to stimulating their potential.

Lastly, bolstering teachers' confidence and beliefs in their teaching process is crucial for enhancing their self-efficacy. According to Bandura, the external environment significantly influences self-efficacy [

69]. School leaders play a key role in creating a supportive climate, offering timely guidance, and providing external support to boost teachers' self-efficacy. Diversified training opportunities are pivotal for deeper professional knowledge and skills mastery, reinforcing professionalism. Encouraging teachers to develop unique curricula and use diverse teaching methods bolsters their confidence in handling their work, thereby enhancing their sense of achievement and value. Teachers themselves should actively build their self-efficacy by recording successful teaching experiences, comparing teaching outcomes, and engaging in professional development through collaboration and exchange with peers.

7. Limitations

The study's conclusions were drawn through quantitative research methods utilizing relatively homogeneous data. To further substantiate and broaden these findings, future research could incorporate qualitative or mixed methods for data collection.

Moreover, this study employed cross-sectional data, constructing relationships between variables based on existing theories and prior literature. Yet, the determination of causal relationships remains incomplete. Future research employing longitudinal tracking could delve deeper into the causal links and dynamic characteristics among distributed leadership, student-centered teaching practices, teacher self-efficacy, and social and emotional competence.

Lastly, potential additional mediating pathways between distributed leadership and students' social-emotional competence warrant exploration in future research endeavors.

8. Conclusions

The study aimed to explore the connections between distributed leadership, student-centered instructional practices, teacher self-efficacy, and students' social-emotional competence. It revealed that distributed leadership, student-centered instructional practices, and teacher self-efficacy significantly impact students' social-emotional competence. Additionally, the study found that student-centered instructional practices and teacher self-efficacy serve as mediators in the relationship between distributed leadership and students' social-emotional competence. Moreover, implementing student-centered instructional practices can notably enhance teachers' self-efficacy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and Q.L.; Methodology, Z.L.; Data analysis, Z.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, Z.L., Q.L. and W.L.; Review and editing, Q.L. and W.L.; Supervision, Q.L.; Funding acquisition, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 2019 Major Project of Key Research Base of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education, "Research on the Evaluation System of the Quality of Teacher Education in China", grant number 19JJD880001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to openness and availability of the data. The data of this study were taken from the public data provided by OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills, which is easily available on this website

https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/social-emotional-skills-study/data.htm., and is not collected by the researchers. The OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills is an international survey that identifies and assesses the conditions and practices that foster or hinder the development of social and emotional skills for 10- and 15-year-old students. So, our research used the secondary data, which everyone can access on Internet.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- OECD. Beyond Academic Learning: First Results from the Survey of Social and Emotional Skills; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Osher, D.; Kidron, Y.; Brackett, M.; Dymnicki, A.; Jones, S.; Weissberg, R. P. Advancing the Science and Practice of Social and Emotional Learning: Looking Back and Moving Forward. Rev. Res. Educ. 2016, 40(1), 644–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Shute, V. J. The Influence of Non-cognitive Domains on Academic Achievement in K-12. Ets Research Report 2009, 2009(2), i–51. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak, J. A.; Weissberg, R. P.; Dymnicki, A. B.; Taylor, R. D.; Schellinger, K. B. The Impact of Enhancing Students' Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Dev. 2011, 82(1), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Hu, B. Y.; Song, Z. Child routines mediate the relationship between parenting and sociale-motional development in Chinese children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 98, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghans, L.; Duckworth, A. L.; Heckman, J. J.; ter Weel, B. The Economics and Psychology of Personality Traits. J. Hum. Resour. 2008, 43(4), 972–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, P.; Lee, S. Trends in Quality-Adjusted Skill Premia in the United States, 1960-2000. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101(6), 2309–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13(4), 423–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Leithwood, K.; Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Hopkins, D. Distributed leadership and organizational change: Reviewing the evidence. J. Educ. Chang. 2007, 8(4), 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, D. G. Distributed leadership, professional collaboration, and teachers' job satisfaction in US schools. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 79, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Xia, J. Teacher-perceived distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: A multilevel SEM approach using the 2013 TALIS data. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 92, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellibas, M. S.; Gumus, S.; Liu, Y. Does school leadership matter for teachers' classroom practice? The influence of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on instructional quality. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2021, 32(3), 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amels, J.; Kruger, M. L.; Suhre, C. J. M.; van Veen, K. The effects of distributed leadership and inquiry-based work on primary teachers' capacity to change: testing a model. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2020, 31(3), 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektas, F.; Kilinc, A. C.; Gumus, S. The effects of distributed leadership on teacher professional learning: mediating roles of teacher trust in principal and teacher motivation. Educ. Stud. 2022, 48(5), 602–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G.; Rosseel, Y. The relationship between the perception of distributed leadership in secondary schools and teachers' and teacher leaders' job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2009, 20(3), 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bellibas, M. S.; Gumus, S. The Effect of Instructional Leadership and Distributed Leadership on Teacher Self-efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Mediating Roles of Supportive School Culture and Teacher Collaboration. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 49(3), 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Leadership for learning: lessons from 40 years of empirical research. J. Educ. Admin. 2011, 49(2), 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, R. H.; Hallinger, P. Testing a longitudinal model of distributed leadership effects on school improvement. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21(5), 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witziers, B.; Bosker, R. J.; Krüger, M. L. Educational leadership and student achievement:: The elusive search for an association. Educ. Admin. Q. 2003, 39(3), 398–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J. D. Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 1990, 9 (3), 185-211.

- Bar-On, R. By BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory. 1997.

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ; learning, 1996.

- Wigelsworth, M.; Humphrey, N.; Kalambouka, A.; Lendrum, A. A review of key issues in the measurement of children’s social and emotional skills. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2010, 26(2), 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2013 CASEL guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs-Preschool and elementary school edition. 2013. Available online: https://casel.org/wp-content/ uploads/2016/01/2013-casel-guide-1.pdf.

- Abrahams, L.; Pancorbo, G.; Primi, R.; Santos, D.; Kyllonen, P.; John, O. P.; De Fruyt, F. Social-Emotional Skill Assessment in Children and Adolescents: Advances and Challenges in Personality, Clinical, and Educational Contexts. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31(4), 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, O.; Robins, R.; Pervin, L. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; Guilford Press, 2010.

- Gibb, C.A. Leadship//G Lindzey(Ed); Handbook of Social Psychology(Vol.2); Cambridge, MA: Addison Wesley, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R. D. Conceptualizing leadership with respect to its historical-contextual antecedents to power. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13(2), 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, R.; Gold, J.; Lawler, J. Locating Distributed Leadership. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13(3), 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, S.; Higgs, M.; Wuerz, T. Pilots for change: exploring organisational change through distributed leadership. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2014, 35(2), 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. P.; Healey, K. Conceptualizing School Leadership and Management from a Distributed Perspective: An Exploration of Some Study Operations and Measures. Elem. Sch. J. 2010, 111(2), 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. P. Distributed Leadership; San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2006.

- Schleicher, A. TALIS 2018: Insights and Interpretations; Paris: OECD, 2018.

- Kilinc, A. C.; Polatcan, M.; Turan, S.; ozdemir, N. Principal job satisfaction, distributed leadership, teacher-student relationships, and student achievement in Turkey: a multilevel mediated-effect model. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Distributed leadership practices and student science performance through the four-path model: examining failure in underprivileged schools. J. Educ. Admin. 2021, 59(4), 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q. The relationship between distributed leadership and teacher innovativeness: Mediating roles of teacher autonomy and professional collaboration. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghia, T. L. H.; Phuong, P. T. N.; Huong, T. L. K. Implementing the student-centred teaching approach in Vietnamese universities: the influence of leadership and management practices on teacher engagement. Educ. Stud. 2020, 46(2), 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellotti, M. L. Do interactive learning spaces increase student achievement? A comparison of classroom context. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2018, 19(3), 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldnes, N. The flipped classroom and cooperative learning: Evidence from a randomised experiment. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2016, 17(1), 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, P.; Patel, M.; Johnson, E.; Weiss, M. Active Learning and Student-centered Pedagogy Improve Student Attitudes and Performance in Introductory Biology. CBE-Life Sci. Educ. 2009, 8 (3), 203-213.

- Wang, S.; Zhang, D. Student-centred teaching, deep learning and self-reported ability improvement in higher education: Evidence from Mainland China. IInnov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2019, 56(5), 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bellibas, M. S.; Gumus, S. The Effect of Instructional Leadership and Distributed Leadership on Teacher Self-efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Mediating Roles of Supportive School Culture and Teacher Collaboration. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 49(3), 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teaching and Learning International Survey ( TALIS) 2018: Conceptual Framework. Available online: http: / /doi.org / /10.787 /799337c2-en, 2018-11-12 /2020-3-30.

- Hettinger, K.; Lazarides, R.; Schiefele, U. Motivational climate in mathematics classrooms: teacher self-efficacy for student engagement, student- and teacher-reported emotional support and student interest. ZDM-Math. Educ. 2023, 55 (2), 413-426.

- Hettinger, K.; Lazarides, R.; Rubach, C.; Schiefele, U. Teacher classroom management self-efficacy: Longitudinal relations to perceived teaching behaviors and student enjoyment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaseen, W. S.; Al-Musaileem, M. Y. Teacher empowerment as an important component of job satisfaction: a comparative study of teachers' perspectives in Al-Farwaniya District, Kuwait. Compare 2015, 45(6), 863–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qiang, F.; Kang, H. Distributed leadership, self-efficacy and wellbeing in schools: A study of relations among teachers in Shanghai. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun.2023, 10 (1).

- Duyar, I.; Gumus, S.; Sukru Bellibas, M. Multilevel analysis of teacher work attitudes. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2013, 27(7), 700–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yin, H.; Liu, Y. The Relationship Between Distributed Leadership and Teacher Efficacy in China: The Mediation of Satisfaction and Trust. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2019, 28 (6), 509-518.

- Kilinc, A. C.; Polatcan, M.; Cepni, O. Exploring the association between distributed leadership and student achievement: the mediation role of teacher professional practices and teacher self-efficacy. J. Curric. Stud. 2023, 55(3), 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, B. How does learner-centered education affect teacher self-efficacy? The case of project-based learning in Korea. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 85, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzberger, D.; Philipp, A.; Kunter, M. How Teachers' Self-Efficacy Is Related to Instructional Quality: A Longitudinal Analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105(3), 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhsari, M.; Chen, J.; Baniasad, S. Multilevel analysis of teacher professional well-being and its influential factors based on TALIS data. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2023, 18(3), 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Skills for social progress: The power of social emotional skills; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang, J; Tang, Y. P; Guo, J. J; Shao, Z. F. The Technical Report on OECD Study on Social and Emotional Skills of Chinese Adolescence. JOURNAL OF EAST CHINA NORMAL UNIVERSITY, 2021, 39(09), 109-126.

- Dedication. In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Cohen, J., Ed. Academic Press: 1977; p v.

- Heck, R. H.; Hallinger, P. Testing a longitudinal model of distributed leadership effects on school improvement. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21(5), 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Sun, J.; Schumacker, R. How School Leadership Influences Student Learning: A Test of "The Four Paths Model". Educ. Admin. Q. 2020, 56(4), 570–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk A. S; Sebring P. B; Allensworth E; et al. Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago; University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- [Camburn E. M; Han S. W. Investigating connections between distributed leadership and instructional change//Harris A. Distributed Leadership; Netherlands: Springer, 2009.

- Clutter-Shields, J.L. Does Distributed Leadership Influence the Decision Making of Teachers in the Classroom: Examining Content and Pedagogy; University of Kansas. 2011.

- Muijs, D.; Harris, A.; Chapman, C.; Stoll, L.; Russ, J. Improving Schools in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Areas – A Review of Research Evidence. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 2004, 15(2), 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M. Distributed leadership and teachers’ self-efficacy: the case studies of three Chinese schools in Shanghai. 2011.

- Spillane, J. P.; Halverson, R.; Diamond, J. B. Investigating School Leadership Practice: A Distributed Perspective. Educ. Researcher 2001, 30(3), 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. A. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 2006, 314(5805), 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, A. Distributed Leadership and School Improvement: Leading or Misleading? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2004, 32(1), 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).