1. Introduction

Globally, cervical cancer ranks fourth in terms of incidence and mortality. In Romania, it represents a significant public health issue due to the elevated rates of incidence and mortality, among the highest (ranks second) in Europe [

1,

2]. Like other gynecologic cancers, the rates are higher in Central and Eastern Europe than in the rest of the continent [

3].

There are several causes responsible for this unfavorable situation. Firstly, there is no national screening program for cervical cancer which often leads to late-stage diagnosis. Secondly, there is a lack of an active and sustained vaccination campaign against HPV for the female population. Lastly, it is relatively difficult to access radiation centers [

4]. As a consequence, cervical cancer ranks third among all neoplastic localizations in Romania in terms of incidence [

1].

While there is no formal definition for the term "locally advanced cervical cancer," there is a broad consensus that includes stages IB2 (AJCC 2017)/IB3 (FIGO 2018)-4A [

5]. These stages are considered to carry an increased risk of local recurrence and, or metastasis [

6] and thus require more aggressive treatment [

7].

All current therapeutic guidelines consider that the treatment for locally advanced cervical cancer should be concurrent chemoradiotherapy [

8,

9]. An exception is made for stages IB3 and IIA2, for which radical surgery (hysterectomy) is proposed either alone or after concurrent chemoradiotherapy [

8]. However, in Romania, it is common practice to perform surgery after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer, which significantly deviates from the unanimously accepted therapeutic guidelines (ESGO/ESTRO/ESP or NCCN) [

4,

10]. These guidelines recommend definitive radiotherapy (external radiotherapy + radio-sensitizing chemotherapy + brachytherapy) with a total dose of 80-90Gy at point A. It is worth noting that the current medical practice in Romania for treating certain conditions involves administering external irradiation with a total dose of 45-50Gy, alongside weekly doses of Cisplatin at 40mg/m2 (5 administrations), followed by brachytherapy (or not) at a dose of only 15Gy. Thus, the total dose at point A amounts to merely 60-65Gy, well below the standard set by therapeutic guidelines. After 6-8 weeks of chemoradiotherapy, cases that respond well and become operable (partial or complete responders) undergo surgery. For these cases, radical hysterectomy or extra fascial hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy is performed, with or without lymph node sampling or latero-aortic lymphadenectomy [

4,

10].

A serious issue arises in patients who do not respond to concurrent chemoradiotherapy or experience disease progression. These patients are left with suboptimal doses and are only monitored clinically and via imaging techniques. Thus, they remain undertreated according to current standards. This category of patients, who are therapeutically abandoned and not included in any evaluation or study in Romania, presents an oncological challenge due to the high rate of therapeutic failure, consequently leading to unfavorable outcomes in the majority of cases.

Regarding the assessment of treatment response to chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer patients, 18F-FDG PET/CT seemed to exhibit superior diagnostic accuracy compared to other imaging modalities. MRI has shown a notably low sensitivity in identifying metastases, but PET/CT demonstrated much superior performance. Nevertheless, there was no substantial disparity seen in the diagnosis of residual illness between these two approaches, as it was explained by Sistani [

11].

According to a research by Fleischmann [

12], there is a lack of a wide range of molecular markers that can be used to accurately predict how patients will respond to medication and how long they will survive. Additionally, there is a need to identify people who have either a high or low risk of developing certain conditions. Nevertheless, the use of these indicators might enhance treatment outcomes and facilitate the development of novel targeted medicines. As an example of these previous statements, a study by Du [

13] underlined that ERCC1 has been identified as a very promising biomarker for cervical cancer. Analysis of ERCC1 polymorphism suggests that it might serve as a valuable tool for predicting the likelihood of developing cervical cancer and the potential hazardous side effects of therapy. Another marker that has proven useful in predicting the tumor response to neoadjuvant treatment was a high pretreatment level of squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC Ag), that is linked to large tumors and a low chance of survival in patients with cervical cancer who undergo definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT). Physicians may use SCC Ag levels to inform their decision-making process for surgery, hence minimizing the risks associated with dual treatment techniques. An increased level of SCC Ag is linked to resistance to radiation, and the pace at which SCC Ag decreases during concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) may serve as an indicator of tumor response after treatment, as demonstrated also by Fu [

14].

As stated also by Rosolen [

15], MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have a role in controlling mitochondrial activity and maintaining balance, as well as influencing cell metabolism. They do this by targeting certain oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that are part of metabolic-related signaling pathways associated with the fundamental characteristics of cancer. The functions of miRNAs and their respective target genes have mostly been documented in cellular metabolic processes, mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, apoptosis, redox signaling, and resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs. Collectively, these results confirm the involvement of miRNAs in the metabolic reprogramming characteristic of cancer cells and emphasize their potential as predictive molecular indicators for therapy response and/or targets for therapeutic intervention.

The contraction of HPV may lead to the development of cancer, and conventional therapies often lead to the reappearance of the disease. The validation of liquid biopsy using HPV circulating tumor DNA (HPV ctDNA) as a potential diagnostic for predicting recurrence in HPV-related malignancies had yet to be determined. According to a study conducted by Karimi, HPV infection has the potential to induce cancer, and conventional therapies often lead to relapse. The validation of liquid biopsy using HPV circulating tumour DNA (HPV ctDNA) as a potential indicator for predicting recurrence in HPV-related malignancies is still pending, according to the conclusion of a study by Karimi [

16].

Cuproptosis has been implicated in the process of carcinogenesis and the advancement of cancer. Nevertheless, the clinical effects of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) associated to cuproptosis (CRLs) in cervical cancer (CC) are not well understood. A research was conducted in order to discover novel biomarkers that can accurately forecast prognosis and assess the effectiveness of immunotherapy, with the ultimate goal of enhancing this scenario. An analysis was conducted to assess the potential efficacy of the prognostic signature in predicting the response to immunotherapy and the susceptibility to chemotherapeutic medicines. Kong [

17] generated a risk signature consisting of eight long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) associated with cuproptosis (AL441992.1, SOX21-AS1, AC011468.3, AC012306.2, FZD4-DT, AP001922.5, RUSC1-AS1, AP001453.2) to predict the survival outcome of patients with CC. We then assessed the reliability of this risk signature. Utilizing our 8-CRLs risk signature, we conducted an independent evaluation of the effectiveness and responsiveness to immunotherapy in patients with CC. This signature has the potential to enhance clinical decision-making for personalized treatment.

As explained by Lakomy [

18], the immunological interactions involved in the genesis, progression, and therapy of cervical cancer are intricate. Compelling evidence supports the notion that lymphopenia and an increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio are predictive of unfavorable outcomes, while other markers also show possible connections. In the context of aggressive medical treatments, there is also the important matter which concerns people with various degrees of immunodepression, for instance: the infection with HIV. Connected to this theme, the majority of studies examined by Shah [

19] indicated that there were no disparities in treatment outcomes, such as: overall toxicity, treatment response, or death, based on the HIV infection status.

In which concerns the “direct monitoring” of the response to treatment, a paper by Schernberg [

20] showed that adaptive radiation is based on the ability to monitor changes in the structures of target volumes in order to make adjustments to the treatment plan during radiotherapy. This approach considers both internal movements and the reaction of the tumour. The use of MRI technology in radiotherapy linear accelerators has made it possible to monitor motion during the administration of treatment. MRI may also be used to precisely assess the remaining volume of cervical tumours after chemo radiotherapy, enabling personalized treatment planning for brachytherapy boost, taking into account the tumor’s radiosensitivity.

Outcome prediction models may assist in making relevant therapeutic choices due to the many variables that might predict the response of cervical cancer to therapy. The prediction models for cervical cancer toxicity, local or distant recurrence, and survival provide promising outcomes with an acceptable level of prediction accuracy, as it was presented by Jha [

21].

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at the Institute of Oncology Bucharest, the oncology center with the highest volume of diagnosed and treated cases of cervical cancer in Romania. The Institutional Bioethics Committee has approved the study. The study includes 351 patients with cervical cancer stages IB3 - IIIB, according to FIGO staging criteria, treated between January 2015 and December 2021 by the same multidisciplinary team and according to the same investigations and treatment protocol, evaluated from a total of 383 cases. All patients underwent the following investigations: chest X-ray/ thoracic CT Scan, pelvis and abdomen MRI/ PET-CT scan/ CT scan, and cystoscopy/ colonoscopy for suspicion of bladder or recto-sigmoid invasion. The treatment protocol consisted of whole pelvis external beam radiation (50.4 Gy), cisplatin (40mg/m²/weekly for 5 days), and brachytherapy to the A point (15 Gy). After 4-6 weeks, another MRI or PET-CT of the pelvis and abdomen is performed for reevaluation in preparation for surgical intervention. After 6-8 weeks: laparotomy followed by type C2 (type III) radical hysterectomy or extra fascial total hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy with or without lateral-aortic lymph node sampling. In cases where there was intraoperative pelvic or latero-aortic lymphatic invasion, only an extra fascial total hysterectomy was performed and these cases were not abandoned. During the same period, a total of 58 patients with locally advanced cervical cancer underwent the same concomitant chemoradiotherapy but experienced unfavorable progression of the disease locally or the development of distant metastases. These patients either underwent laparotomy or received no surgical intervention, leading to therapeutic abandonment. Clinical and imaging follow-up were the only approaches. Laparoscopic approaches or ICG-guided sampling of pelvic lymph nodes, although described as possibilities in literature were not indicated for our patients due to the technical particularities of the cases [

22,

23].

The surgical resection specimens were evaluated for pathologic response, which was classified as either partial (pPR) or complete (cPR). The patient data was analyzed by grouping them into subsets based on their histologic tumor type. We also analyzed the outcomes of each case in terms of recurrence, lymphatic and distant metastasis, and surgery-related morbidity.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the NCSS 2019 software. A two-proportions comparison test was employed to assess the impact of histologic tumor type on complete pathologic response (cPR) and pathological complete regression (PCR). To address potential imbalances in clinical variables among the three tumor categories (squamous carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and adenosquamous carcinoma), we applied a 1:3 propensity score (PS) matching technique. The primary objective of this technique was to diminish inadequate matches between the aforementioned categories. Statistical significance was determined if the p-value was less than 0.05. The data were presented as numerical counts and percentages.

3. Results

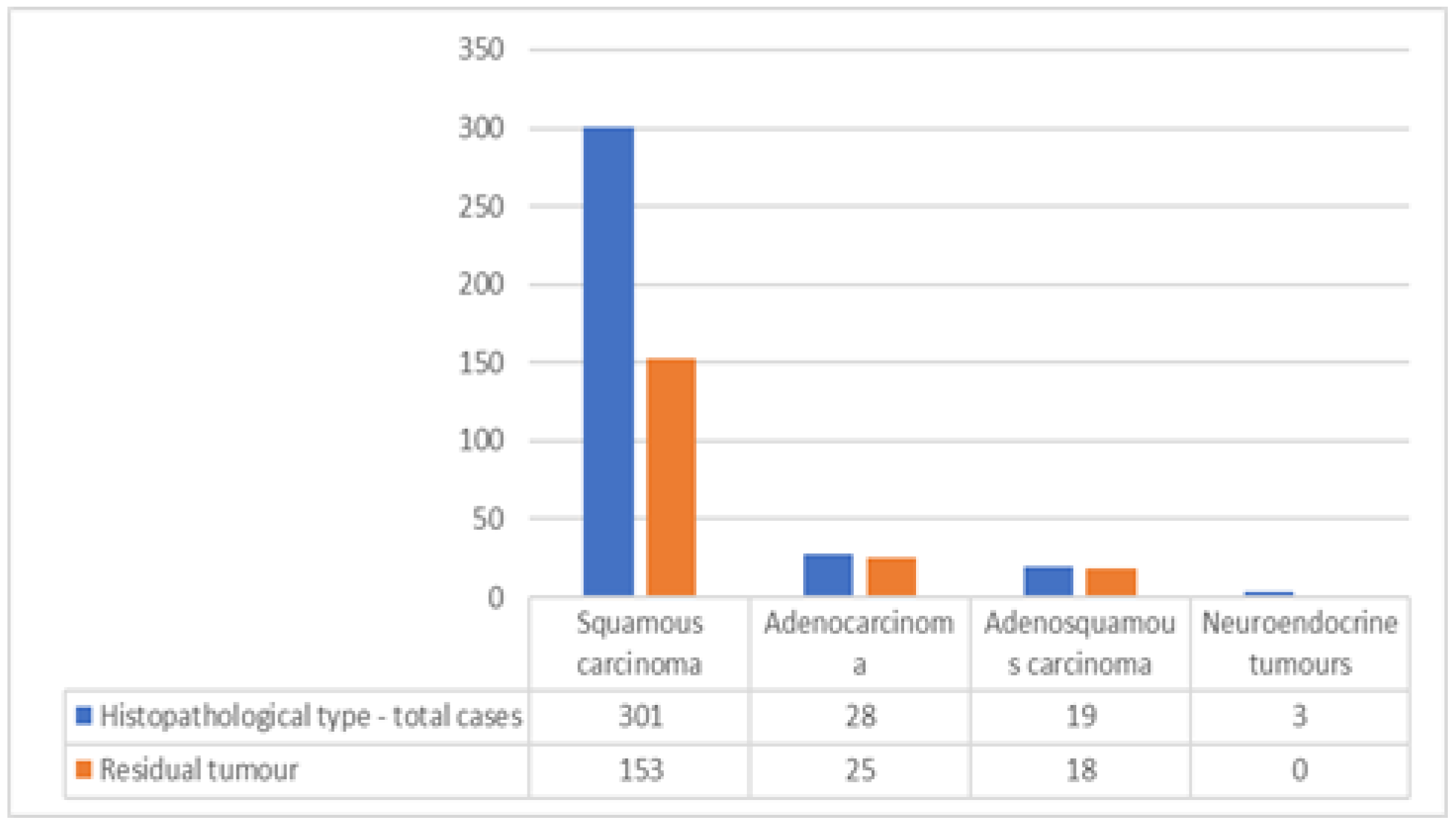

Most of our cases were classified upon histopathologic examination of resected specimens as squamous cell carcinomas - 301 (85,75%). The rest were adenocarcinomas - 28 (7,98%), adenosquamous carcinomas - 19 (5,41%), and neuroendocrine tumors - 3 (0,85%).

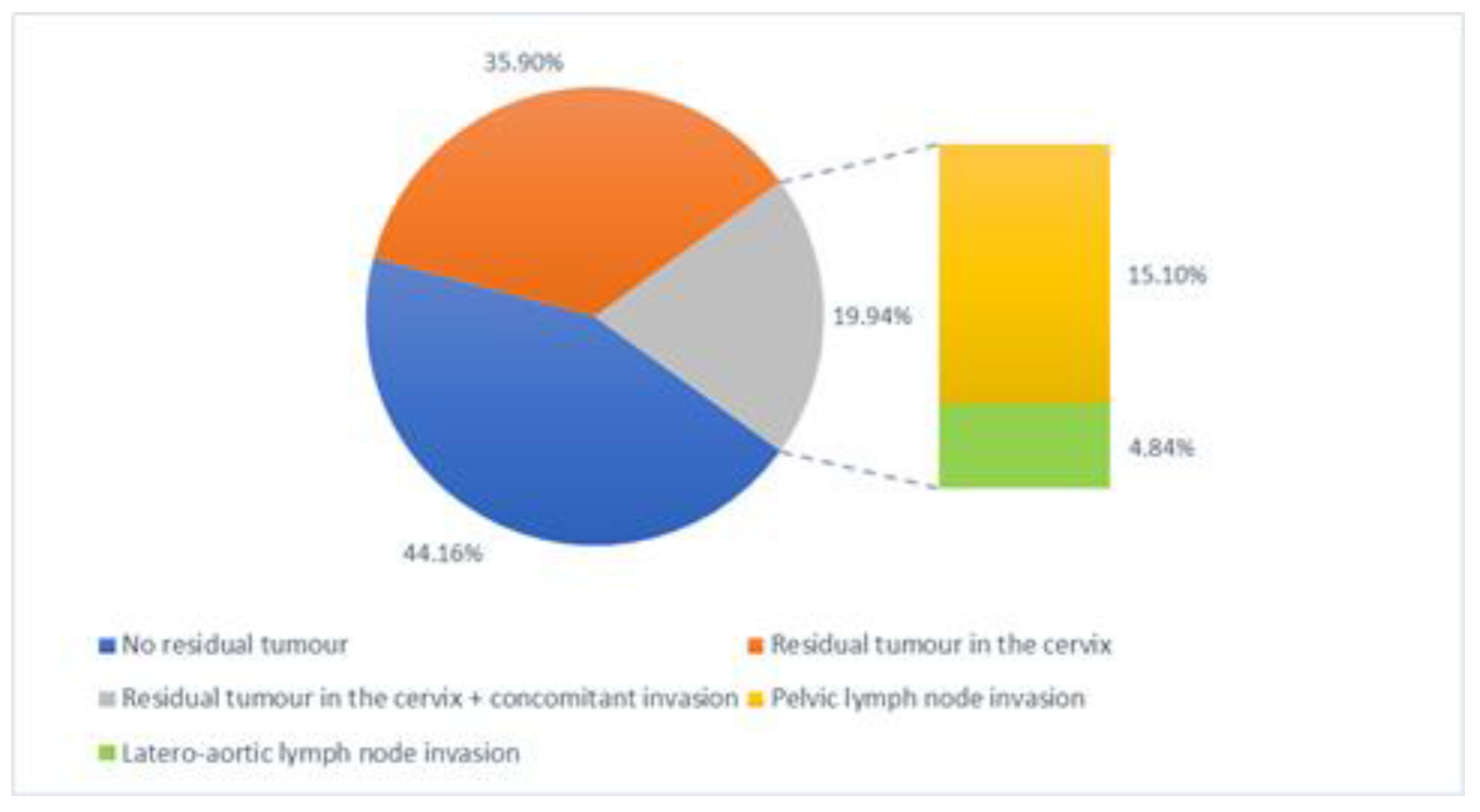

The pathological report of surgical specimens found that in 196 cases (55.84%) the result of the concurrent chemoradiotherapy was a partial pathologic response (pPR) and residual tumor in the cervix was present (

Figure 1). In 70 cases (19.94%), the pathologic examination revealed a concomitant residual tumor of the cervix and pelvic lymph node invasion (53 patients - 15.1%) and latero-aortic lymph node invasion (17 patients - 4.84%). In the 196 cases with pPR after concurrent chemo radiotherapy 139 cases (73.94%) showed a less than 50% reduction of pre-therapeutic tumor size and 49 cases (26.6%) had a pathologic response greater than 50%, with 7 (3.72%) of those having only microscopic residual tumor in the cervix (

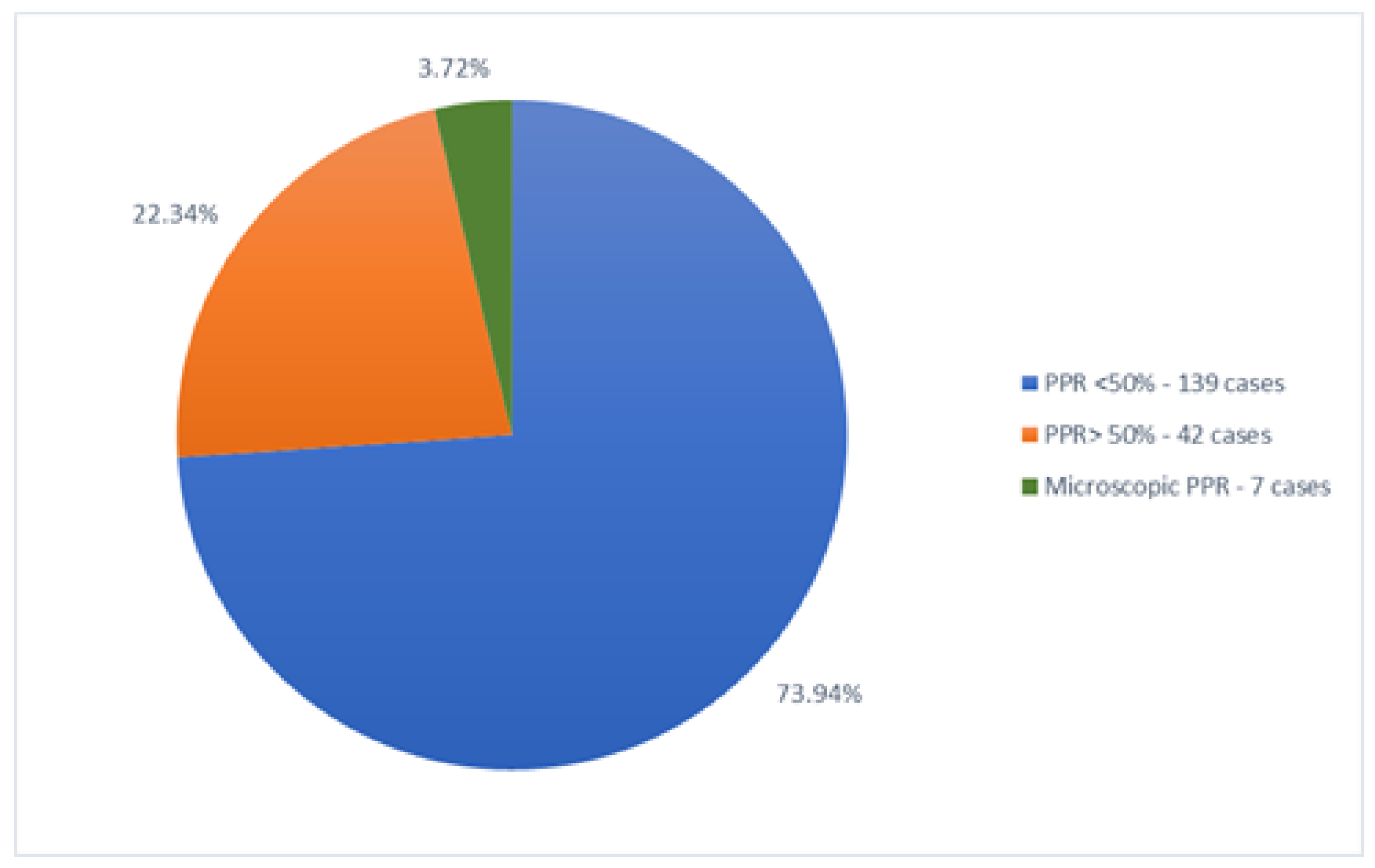

Figure 2).

It is interesting to note that cases of adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma, which are more aggressive tumors, exhibit a higher percentage of residual tumors compared to cases of squamous carcinoma (

Figure 3). This finding is consistent with existing literature [

24].

Additionally, cases with adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma have a much lower rate of complete pathological response (pCR) compared to cases with squamous cell carcinoma.

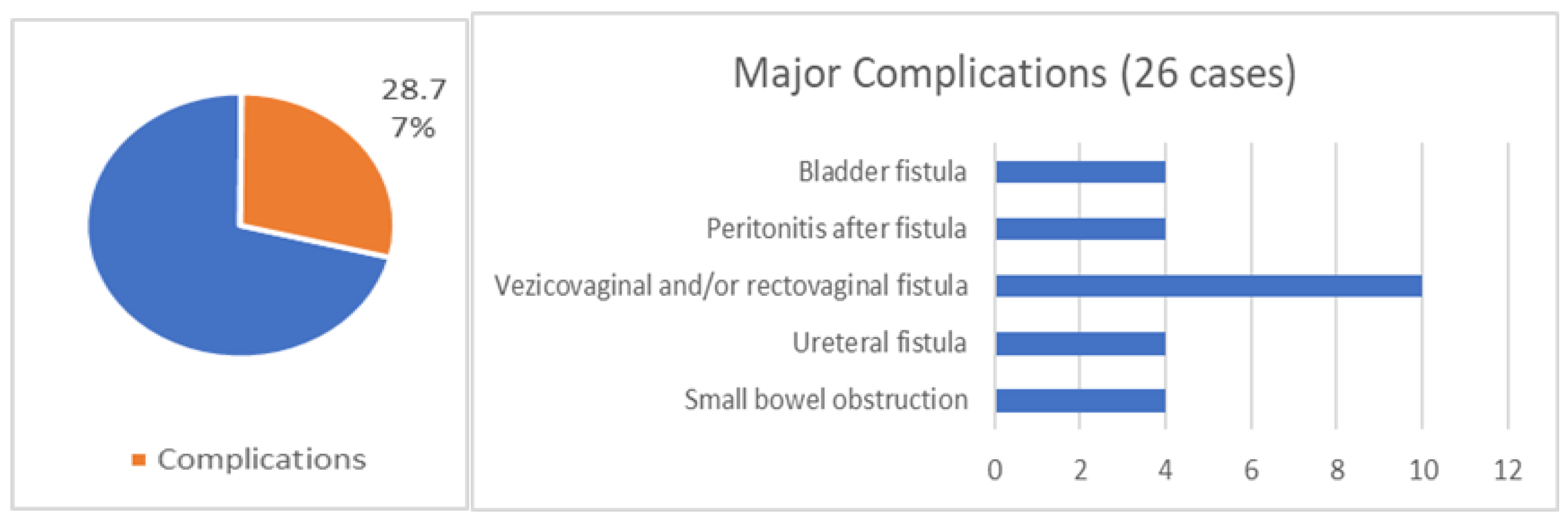

In surgically treated patients, procedure-related complications were seen in 101 cases, including intraoperative incidents and accidents, early complications (first 7 days postoperative), and late complications. There were major complications in 26 cases (7.40%). These included urinary fistulas, complex vesico-vaginal or recto-vaginal fistulas, bowel obstructions, and peritonitis due to bowel perforation.

The recurrence rate in surgically treated patients was 24.21% (85 cases), including locoregional recurrence (pelvic or latero-aortic) and distant metastases (lymphatic, osseous, hepatic, pulmonary) (p<005). The 58 patients with locally advanced cervical cancer who underwent the concomitant chemoradiotherapy but experienced unfavorable progression of the disease locally or the development of distant metastases were either subjected to laparotomy or no surgical intervention was performed, essentially leading to therapeutic abandonment, with clinical and imaging follow-up being the only approach. Typically, these patients are not included in any studies in Romania and fall into a gray area. In this particular group, the recurrence rate was significantly higher (36 cases, 62.1%; p<005), including local, regional, and distant metastatic recurrences.

4. Discussion

It has not been proven that surgery is beneficial after concurrent chemoradiotherapy. It is now widely recognized that this type of surgery does not improve overall or disease-free survival compared to definitive irradiation. However, the postoperative morbidity, particularly urinary tract morbidity, is significantly higher [

25,

26,

27]. Retrospective studies and meta-analyses have shown similar survival after concurrent chemoradiotherapy, with or without subsequent surgery [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Other smaller retrospective studies even suggest a benefit of surgery after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in terms of overall survival (OS) and local disease control [

32], or that it may improve disease-free survival (DFS) without affecting overall survival, specifically for patients with good response to concurrent chemoradiotherapy [

33].

However, after concurrent chemoradiotherapy, residual lesions at the cervical level persist in a variable proportion, ranging from 32-60% across different stages [

25,

28,

34,

35], as also illustrated by our study. The exact prognostic significance of these residual lesions after concurrent chemoradiotherapy remains uncertain, as they are not synonymous with recurrence but do result in significantly worse outcomes; various studies have shown that residual cervical lesions lead to a higher rate of local recurrence [

36,

37]. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy should ensure local control within therapeutic guidelines.

Taking all this into account, the simplest answer to – “why is surgery still done after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer, in Romania?” is - to assess the response to suboptimal concurrent chemotherapy practiced in the country and to achieve better local control. However, it is known that this type of surgery does not improve survival when performed after guideline-stipulated concurrent chemoradiotherapy and is associated with significantly increased additional morbidity, as shown by our study. But in Romania, the radiation doses used in current practice are less than those stipulated. There are several reasons why irradiation is not performed according to international therapeutic guidelines in Romania.

First is the reluctance of radiation therapists to encounter complications from definitive irradiation (rectal/vesical/vaginal fistulas, extensive post-radiation fibrosis, post radiotherapy enteritis with subsequent obstructions), although these complications also occur after the irradiation practiced in our country, leading patients to seek surgical solutions. As a result, definitive irradiation is rarely carried out in Romania.

Another challenge is the limited access that patients have to radiation centers. Although Romania has several such centers, they are mostly concentrated in a few university centers, causing delays in getting enrolled for irradiation. As a result, only a small percentage of patients are eligible for the treatment. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that the quality of irradiation is uneven across different centers, leading to unpleasant post-irradiation complications that are difficult to manage.

Thirdly, the socioeconomic conditions, particularly in Romania, which has an average level of development, do not allow for the performance of all tests and investigations required to ensure proper follow-up for all patients, as described by other studies [

38]. Due to economic conditions and low health literacy, Romanians often delay preventive health measures.

Sometimes, due to a lack of access to radiation therapy or suboptimal neoadjuvant therapy, surgery replaces it, leading to the overuse of surgery to achieve better local control, especially in cases of locally advanced cervical cancer. Residual lesions can be surgically removed for better local control after concurrent chemoradiotherapy, according to studies [

25,

34,

39].

Of course, we asked ourselves if we could replace the surgical assessment of the definitive chemoradiotherapy with a less invasive method. The alternative, imaging studies, does not allow for a very accurate assessment. After concurrent chemoradiotherapy, MRI is the most useful tool for assessing residual lesions due to its high predictive value and low false negative rate [

40,

41]. However, there is a discrepancy between the control pelvic MRI (performed after concurrent chemoradiotherapy) and the pathologic response evaluated on the resection specimen which in our case occurred in 38 patients.

It is a fact that in Romania, we perform this type of surgery after concurrent chemoradiotherapy. The question to answer is what are its indications and for which cases such surgery is useful? Currently, in Romania, clinical and imaging assessments are conducted at 4-6 weeks, and the gynecologic oncologist decides if the intervention can be technically performed or not, as described in our study. However, coherent and reasoned indications for this type of surgery should exist, even though they do not presently. In our opinion, surgery should only be performed for cases with a complete clinical and imaging response post concurrent chemoradiotherapy. For these cases, performing surgery has been suggested, but only a total extra fascial hysterectomy accompanied by pelvic lymphadenectomy is proposed to reduce postoperative morbidity by avoiding the parametrial direction of the ureter [

41,

42]. Another possibility would be surgery after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for cases without clinical and imaging response or those with disease progression, which could improve prognosis by excising larger lesions [

35]. Another approach would be surgery for cases with unfavorable histopathology, i.e., cases with adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma, known for their more aggressive progression [

24], and in which our study also showed a very high percentage of residual cervical lesions post concurrent chemoradiotherapy. In cases like these, a weak response to treatment is highly likely, so adjuvant surgery may offer better local control. Recently, for advanced cases (stage IVa or lower but associated with complex fistulas between the pelvic organs), extensive surgery is sometimes indicated when the resection is technically possible – pelvic exenterations have been performed for such cases with encouraging results [

5,

9], in some cases even having radical curative intent.

The final question to answer is how can we determine the utility of this type of surgery for locally advanced cervical cancer? Given the current therapeutic approach in Romania, there is a need for large prospective studies to compare outcomes in terms of survival and complication rates with and without adjuvant surgery. Another approach, as described by Querleu [

43], would involve more effective technical irradiation or new cytostatic drugs for better radio sensitization or the implementation at a national level of standardized procedures for concurrent chemoradiotherapy —methods that by increasing the effectiveness of neoadjuvant therapy and would make adjuvant surgery unnecessary or significantly reduce its use.

5. Conclusions

While not yet confirmed conceptually, the practice of performing surgery after concurrent chemotherapy is currently being utilized in Romania. Our research found that over 50% of excised specimens contained residual lesions. In the context of suboptimal radiotherapy, surgery aims to achieve better local control at the cost of increased morbidity. As long as the conditions of radiotherapy in Romania do not improve, surgery will continue to maintain a dominant position in the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Silviu Voinea and Laurentiu Simion; Data curation, Cristian Ioan Bordea, Razvan Andrei, Sinziana-Octavia Ionescu and Mihnea Alecu; Formal analysis, Silviu Voinea, Cristian Ioan Bordea, Sinziana-Octavia Ionescu and Cristina Capsa; Funding acquisition, Cristina Capsa and Mihnea Alecu; Investigation, Silviu Voinea, Elena Chitoran, Vlad Rotaru and Cristina Capsa; Methodology, Nicolae Mircea Savu; Project administration, Laurentiu Simion; Resources, Vlad Rotaru, Razvan Andrei, Dan Luca and Mihnea Alecu; Software, Razvan Andrei and Dan Luca; Supervision, Nicolae Mircea Savu and Laurentiu Simion; Validation, Nicolae Mircea Savu and Laurentiu Simion; Visualization, Cristian Ioan Bordea and Dan Luca; Writing – original draft, Silviu Voinea; Writing – review & editing, Elena Chitoran, Sinziana-Octavia Ionescu and Laurentiu Simion.

Funding

The authors hope that “Publication of this paper will be supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Bucharest Institute of Oncology “Prof. Dr. Al. Trestioreanu” (protocol code: 11193, date of approval: August 29th, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Since it involves personal data, due to privacy issues, data will be available upon request by e-mail to C-I.B.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cervix uteri. 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

- Simion, L. et al. Inequities in Cervical Cancer Screening and HPV Vaccination Programs and Their Impact on Incidence/Mortality Rates and the Severity of Disease in Romania. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Simion, L. et al. Analysis of Efficacy-To-Safety Ratio of Angiogenesis-Inhibitors Based Therapies in Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2023, vol. 13 Preprint at. [CrossRef]

- Blidaru, A.; et al. Mind the Gap Between Scientific Literature Recommendations and Effective Implementation. Is There Still a Role for Surgery in the Treatment of Locally Advanced Cervical Carcinoma? Chirurgia (Bucur) 2019, 114, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, O.; Chun, M. Management for locally advanced cervical cancer: new trends and controversial issues. Radiat Oncol J 2018, 36, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Mukherjee, U.; Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, S.; Sarkar, S.K. Pattern of failure with locally advanced cervical cancer- A retrospective audit and analysis of contributory factors. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2018, 19, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, L.; et al. A Decade of Therapeutic Challenges in Synchronous Gynecological Cancers from the Bucharest Oncological Institute. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN Guidelines. Cervical Cancer version 1.2023-April 28, 2023-NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1426.

- Cibula, D.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the management of patients with cervical cancer - Update 2023. Virchows Arch 2023, 482, 935–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voinea, S.; et al. Impact of histological subtype on the response to chemoradiation in locally advanced cervical cancer and the possible role of surgery. Exp Ther Med 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanei Sistani, S.; Parooie, F.; Salarzaei, M. Diagnostic Accuracy of 18F-FDG-PET/CT and MRI in Predicting the Tumor Response in Locally Advanced Cervical Carcinoma Treated by Chemoradiotherapy: A Meta-Analysis. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, M.; et al. Molecular Markers to Predict Prognosis and Treatment Response in Uterine Cervical Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Li, G.; Wu, L.; Huang, M. Perspectives of ERCC1 in early-stage and advanced cervical cancer: From experiments to clinical applications. Front Immunol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, P. The role of squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC Ag) in outcome prediction after concurrent chemoradiotherapy and treatment decisions for patients with cervical cancer. Radiat Oncol 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosolen, D.; et al. MiRNAs Action and Impact on Mitochondria Function, Metabolic Reprogramming and Chemoresistance of Cancer Cells: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Jafari-Koshki, T.; Zehtabi, M.; Kargar, F.; Gheit, T. Predictive impact of human papillomavirus circulating tumor DNA in treatment response monitoring of HPV-associated cancers; a meta-analysis on recurrent event endpoints. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 17592–17602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; et al. Identification of cuproptosis-related lncRNA for predicting prognosis and immunotherapeutic response in cervical cancer. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakomy, D.S.; et al. Immune correlates of therapy outcomes in women with cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy: A systematic review. Cancer Med 2021, 10, 4206–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.; Xu, M.; Mehta, P.; Zetola, N.M.; Grover, S. Differences in Outcomes of Chemoradiation in Women With Invasive Cervical Cancer by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Status: A Systematic Review. Pract Radiat Oncol 2021, 11, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schernberg, A.; et al. Incorporating Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Based Radiation Therapy Response Prediction into Clinical Practice for Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer Patients. Semin Radiat Oncol 2020, 30, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction models used in cervical cancer. Artif Intell Med 2023, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirimbei, C.; Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Cirimbei, S. Laparoscopic Approach in Abdominal Oncologic Pathology. In Proceedings of the 35th Balkan Medical Week, Athens, Greece, 25-27 September 2018; pp. 260–265. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000471903700043.

- Simion, L. et al. Indocyanine Green(Icg) And Colorectal Surgery: A Literature Review on Qualitative and Quantitative Methods of Usage. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; et al. Prognosis of Cervical Cancer in the Era of Concurrent Chemoradiation from National Database in Korea: A Comparison between Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0144887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Classe, J.M.; et al. Surgery after concurrent chemoradiotherapy and brachytherapy for the treatment of advanced cervical cancer: morbidity and outcome: results of a multicenter study of the GCCLCC (Groupe des Chirurgiens de Centre de Lutte Contre le Cancer). Gynecol Oncol 2006, 102, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Lu, C.; Yu, Z.; Gao, L. Chemoradiotherapy alone vs. chemoradiotherapy and hysterectomy for locally advanced cervical cancer: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Oncol Lett 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.H.; Kim, S.N.; Chae, S.H.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, S.J. Impact of adjuvant hysterectomy on prognosis in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy: A meta-analysis. J Gynecol Oncol 2018, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motton, S.P.; et al. Results of surgery after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in advanced cervical cancer: comparison of extended hysterectomy and extrafascial hysterectomy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2010, 20, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chereau, E.; et al. The role of completion surgery after concurrent radiochemotherapy in locally advanced stages IB2-IIB Cervical cancer. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Darus, C.J.; et al. Chemoradiation with and without adjuvant extrafascial hysterectomy for IB2 cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2008, 18, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.A.; et al. Survival and recurrence after concomitant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for cancer of the uterine cervix: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2001, 358, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghous, A.; et al. Surgical Resection after Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Cervical Carcinoma. Journal of Oncology Medicine & Practice 2016, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lèguevaque, P.; et al. Completion surgery or not after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011, 155, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houvenaeghel, G.; et al. Long-term survival after concomitant chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery in advanced cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2006, 100, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keys, H.M.; et al. Radiation therapy with and without extrafascial hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma: A randomized trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 2003, 89, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vízkeleti, J.; et al. Pathologic complete remission after preoperative high-dose-rate brachytherapy in patients with operable cervical cancer: preliminary results of a prospective randomized multicenter study. Pathol Oncol Res 2015, 21, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandina, G.; et al. Long-term analysis of clinical outcome and complications in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered concomitant chemoradiation followed by radical surgery. Gynecol Oncol 2010, 119, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, L.; et al. Simultaneous Approach Of Colo-Rectal And Hepatic Lesions In Colo-Rectal Cancers With Liver Metastasis - A Single Oncological Center Overview. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2023, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, T.; Takeshima, N.; Tabata, T.; Hasumi, K.; Takizawa, K. Adjuvant hysterectomy for treatment of residual disease in patients with cervical cancer treated with radiation therapy. Br J Cancer 2008, 99, 1216–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, B.; et al. Cervical cancer response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: MRI assessment compared with surgery. Acta Radiol 2016, 57, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredi, R.; et al. Cervical cancer response to neoadjuvant therapy: MR imaging assessment. Radiology 1998, 209, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morice, P.; et al. Results of the GYNECO 02 study, an FNCLCC phase III trial comparing hysterectomy with no hysterectomy in patients with a (clinical and radiological) complete response after chemoradiation therapy for stage IB2 or II cervical cancer. Oncologist 2012, 17, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abstracts from 18th International Meeting of the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO), 19-22 October 2013, Liverpool, UK. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013, 23, 1–1281. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).