Submitted:

20 December 2023

Posted:

21 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction:

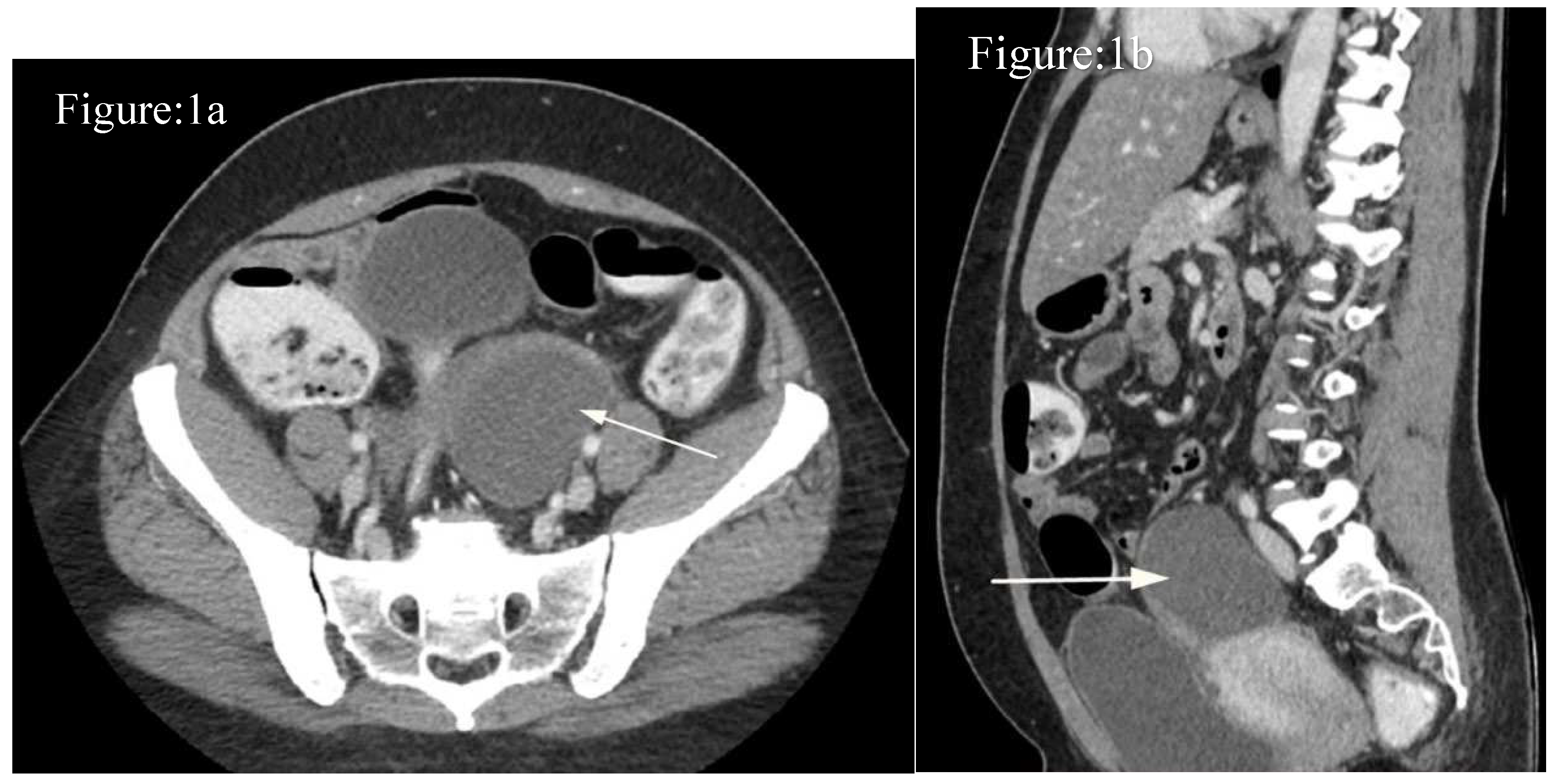

Case-1:

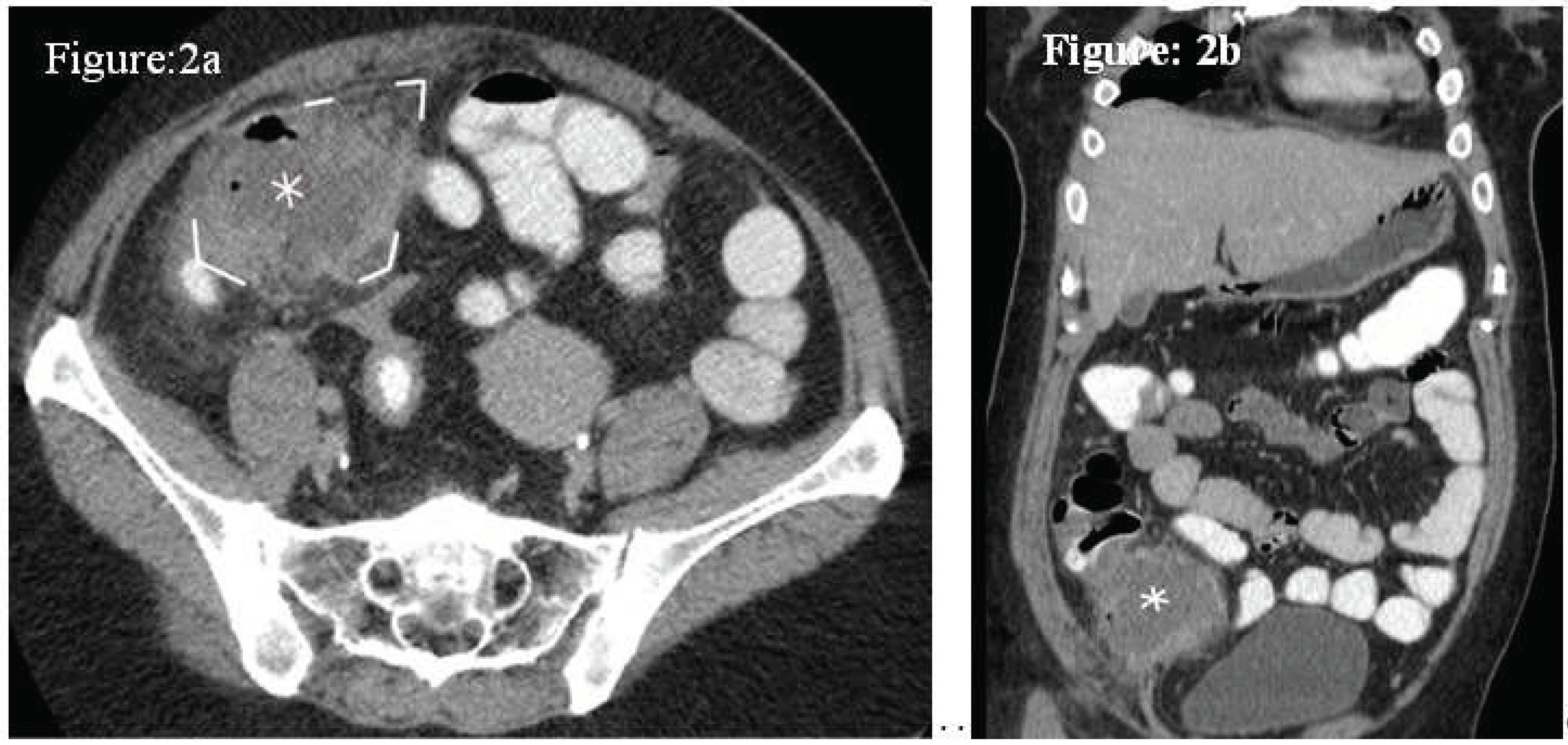

Case 2:

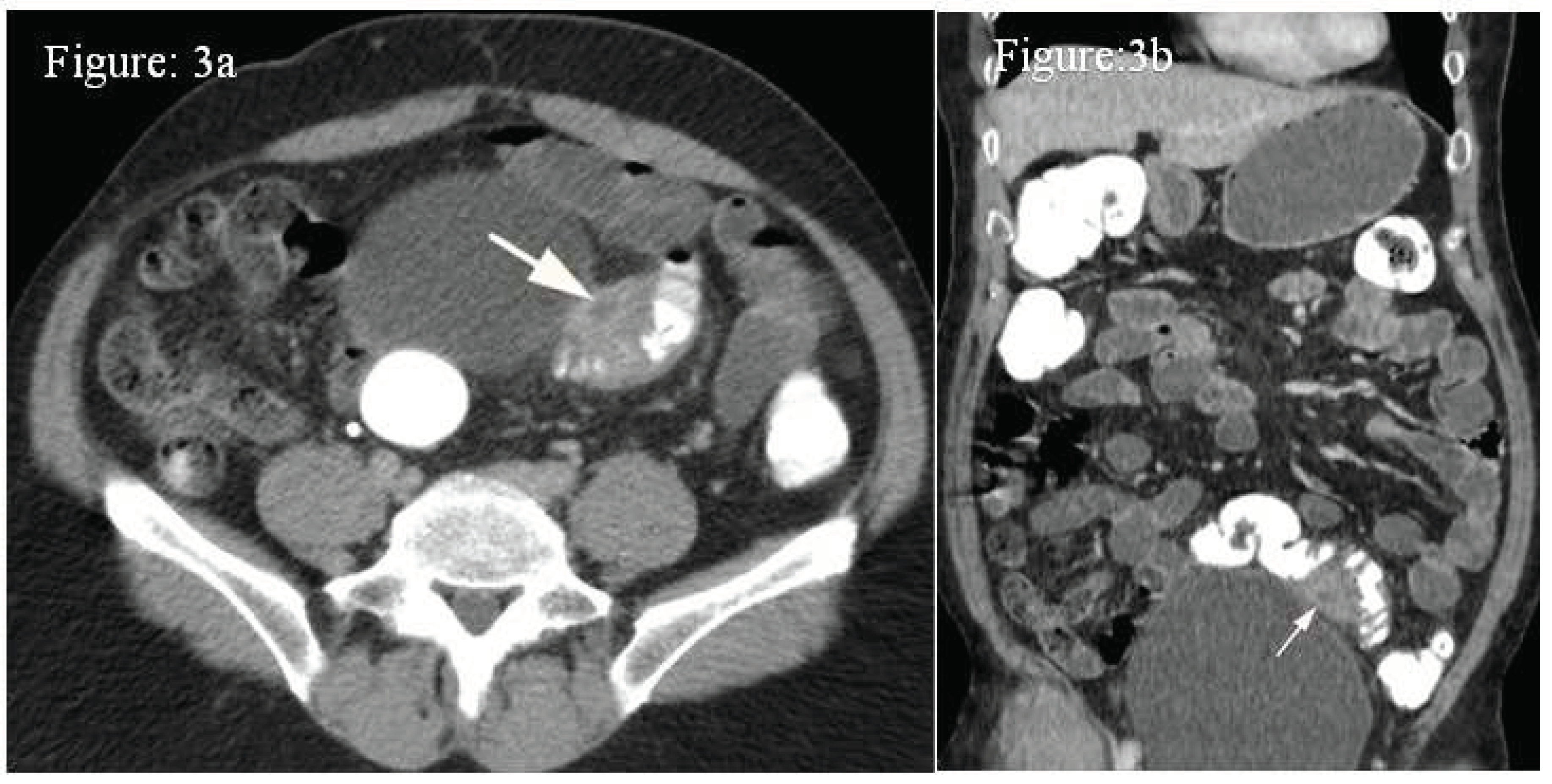

Case 3:

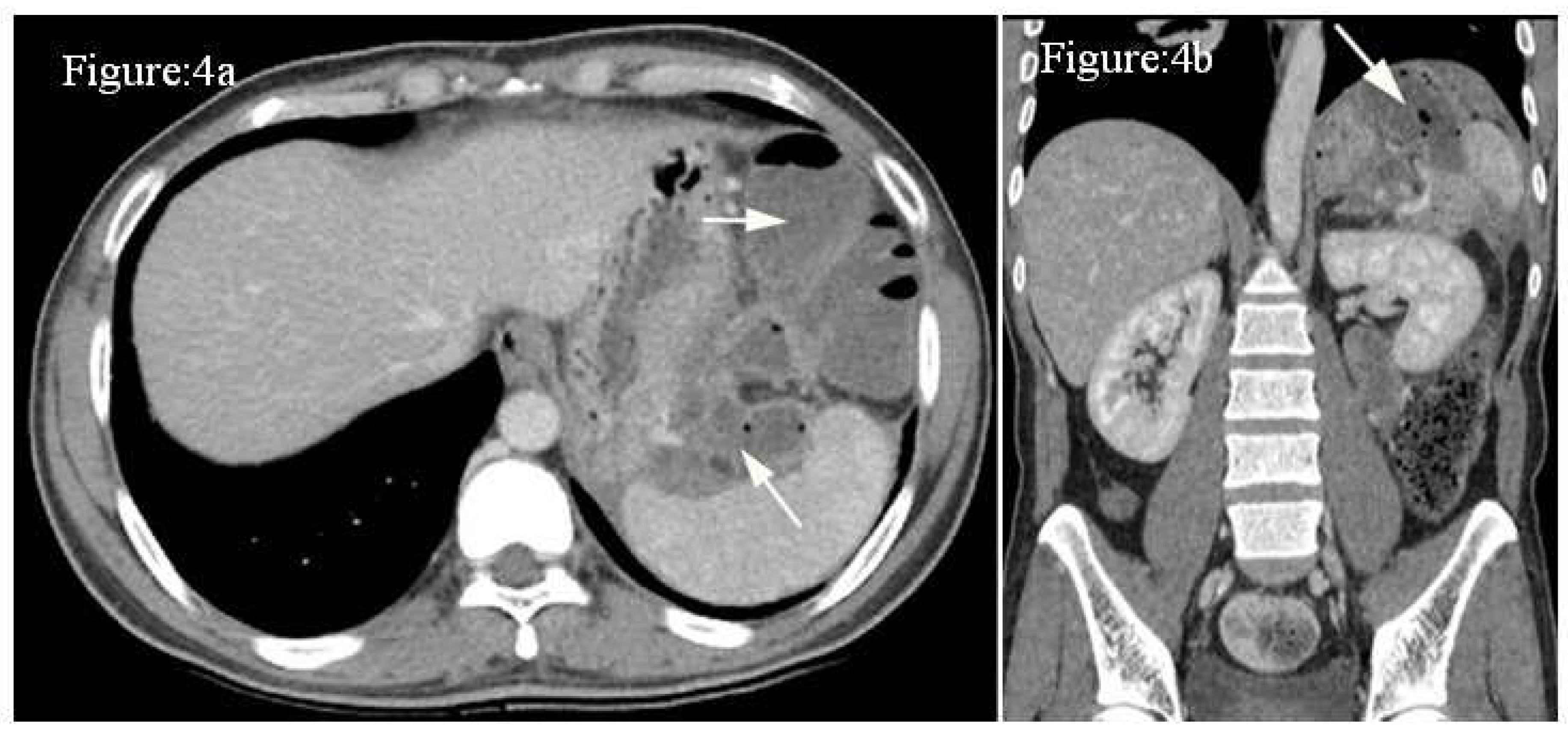

Case 4:

Discussion:

Tubo-ovarian abscess:

Appendicular abscess

Diverticular abscesses

Infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis

USS

CT

MRI

Conclusion:

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval:

References

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins Basic Pathology. 10th ed. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, editors. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier - Health Sciences Division; 2021.

- Zammitt N, Sandilands E. Essentials of Kumar and clark’s clinical medicine. 7th ed. London, England: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

- Schein M. Management of intra-abdominal abscesses. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, editors. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt; 2001.

- Mehta NY, Lotfollahzadeh S, Copelin II EL. Abdominal Abscess. [Updated 2022 Dec 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519573/.

- Zimmermann L, Wendt S, Lübbert C, Karlas T. Epidemiology of pyogenic liver abscesses in Germany: Analysis of incidence, risk factors and mortality rate based on routine data from statutory health insurance. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021 Nov;9(9):1039-1047. [CrossRef]

- Abbas MT, Khan FY, Muhsin SA, Al-Dehwe B, Abukamar M, Elzouki AN. Epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of liver abscess: a single reference center experience in Qatar. Oman Medical Journal. 2014 Jul;29(4):260. [CrossRef]

- Okafor CN, Onyeaso EE. Perinephric Abscess. 2022 Aug 22. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

- Saiki J, Vaziri ND, Barton C. Perinephric and intranephric abscesses: a review of the literature. West J Med. 1982 Feb;136(2):95-102.

- Altemeier WA, Culbertson WR, Fullen WD, Shook CD. Intra-abdominal abscesses. Am J Surg. 1973 Jan;125(1):70-9. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari S, Blaivas M, Lyon M. Role of bedside transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of tubo-ovarian abscess in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2008 May;34(4):429-33. [CrossRef]

- Mayer D, Malfertheiner P, Kemmer TP, Stanescu A, Kuhn K, Büchler M, Ditschuneit H. Wertigkeit von Sonographie und Computertomographie im Nachweis von zystischen Veränderungen bei chronischer Pankreatitis [The value of ultrasound and computerized tomography in detection of cystic changes in chronic pancreatitis]. Z Gastroenterol. 1992 Oct;30(10):709-12.

- Snyder MJ. Imaging of colonic diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004 Aug;17(3):155-62. [CrossRef]

- Sirinek KR. Diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal abscesses. Surgical infections. 2000 Apr 1;1(1):31-8. [CrossRef]

- Munro K, Gharaibeh A, Nagabushanam S, Martin C. Diagnosis and management of tubo-ovarian abscesses. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2018 Jan;20(1):11-9. [CrossRef]

- Chappell CA, Wiesenfeld HC. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of severe pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Dec 1;55(4):893-903. [CrossRef]

- Lambert MJ, Villa M. Gynecologic ultrasound in emergency medicine. Emergency Medicine Clinics. 2004 Aug 1;22(3):683-96. [CrossRef]

- Velcani A, Conklin P, Specht N. Sonographic features of tubo-ovarian abscess mimicking an endometrioma and review of cystic adnexal masses. Journal of Radiology Case Reports. 2010;4(2):9. [CrossRef]

- Krivak TC, Cooksey C, Propst AM. Tubo-ovarian abscess: diagnosis, medical and surgical management. Comprehensive therapy. 2004 Jun;30:93-100. [CrossRef]

- Eo H, Choi HJ, Kim SH, Jung SI, Park BK, Kim SH. Differentiation of tuboovarian abscess from endometriosis: CT indicators. Journal of the Korean Radiological Society. 2005 Oct 1;53(4):273-7. [CrossRef]

- Foti PV, Tonolini M, Costanzo V, Mammino L, Palmucci S, Cianci A, Ettorre GC, Basile A. Cross-sectional imaging of acute gynaecologic disorders: CT and MRI findings with differential diagnosis-part II: uterine emergencies and pelvic inflammatory disease. Insights Imaging. 2019 Dec 20;10(1):118. [CrossRef]

- Bennett GL, Slywotzky CM, Giovanniello G. Gynecologic causes of acute pelvic pain: spectrum of CT findings. Radiographics. 2002 Jul;22(4):785-801. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi S, Makizumi R, Nakahara K, Tsukikawa S, Miyajima N, Otsubo T. Appendiceal abscesses reduced in size by drainage of pus from the appendiceal orifice during colonoscopy: A Report of Three Cases. Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2014 Dec 1;8(3):364-70. [CrossRef]

- Andersson RE, Petzold MG. Nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess or phlegmon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgery. 2007 Nov 1;246(5):741-8. [CrossRef]

- Akingboye AA, Mahmood F, Zaman S, Wright J, Mannan F, Mohamedahmed AYY. Early versus delayed (interval) appendicectomy for the management of appendicular abscess and phlegmon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021 Aug;406(5):1341-1351. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Yousef MM. Ultrasonography of the right lower quadrant. Ultrasound Quarterly. 2001 Dec 1;17(4):211-25. [CrossRef]

- Lane MJ, Liu DM, Huynh MD, Jeffrey Jr RB, Mindelzun RE, Katz DS. Suspected acute appendicitis: nonenhanced helical CT in 300 consecutive patients. Radiology. 1999 Nov;213(2):341-6. [CrossRef]

- Leite NP, Pereira JM, Cunha R, Pinto P, Sirlin C. CT evaluation of appendicitis and its complications: imaging techniques and key diagnostic findings. InPresented at the 2004 Dec 6. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins KL, Patrick LE, Ball TI. Imaging findings of perforative appendicitis: a pictorial review. Pediatr Radiol. 2001 Mar;31(3):173-9. [CrossRef]

- Macari M, Balthazar EJ. The acute right lower quadrant: CT evaluation. Radiologic Clinics. 2003 Nov 1;41(6):1117-36. [CrossRef]

- Hogan MJ. Appendiceal abscess drainage. Techniques in vascular and interventional radiology. 2003 Dec 1;6(4):205-14. [CrossRef]

- Van Sonnenberg E, Wittich GR, Casola G, Neff CC, Hoyt DB, Polansky AD, Keightley A. Periappendiceal abscesses: percutaneous drainage. Radiology. 1987 Apr;163(1):23-6. [CrossRef]

- McCafferty MH, Roth L, Jorden J. Current management of diverticulitis. Am Surg. 2008 Nov;74(11):1041-9. [CrossRef]

- Tursi A, Scarpignato C, Strate LL, Lanas A, Kruis W, Lahat A, Danese S. Colonic diverticular disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Mar 26;6(1):20.

- Andeweg CS, Wegdam JA, Groenewoud J, van der Wilt GJ, van Goor H, Bleichrodt RP. Toward an evidence-based step-up approach in diagnosing diverticulitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul;49(7):775-84. [CrossRef]

- Mazzei MA, Cioffi Squitieri N, Guerrini S, Stabile Ianora AA, Cagini L, Macarini L, Giganti M, Volterrani L. Sigmoid diverticulitis: US findings. Critical Ultrasound Journal. 2013 Dec;5(1):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs DO. Diverticulitis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007 Nov 15;357(20):2057-66.

- Klarenbeek BR, de Korte N, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA. Review of current classifications for diverticular disease and a translation into clinical practice. International journal of colorectal disease. 2012 Feb;27:207-14. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser AM, Jiang JK, Lake JP, Ault G, Artinyan A, Gonzalez-Ruiz C, Essani R, Beart Jr RW. The management of complicated diverticulitis and the role of computed tomography. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG. 2005 Apr 1;100(4):910-7.

- Sartelli M, Moore FA, Ansaloni L, Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Griffiths EA, Coimbra R, Agresta F, Sakakushev B, Ordoñez CA, Abu-Zidan FM. A proposal for a CT driven classification of left colon acute diverticulitis. World journal of emergency surgery. 2015 Dec;10(1):1-1. [CrossRef]

- Heverhagen JT, Sitter H, Zielke A, Klose KJ. Prospective evaluation of the value of magnetic resonance imaging in suspected acute sigmoid diverticulitis. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 2008 Dec;51:1810-5. [CrossRef]

- Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013 Jan;62(1):102-11. [CrossRef]

- Memiş A, Parildar M. Interventional radiological treatment in complications of pancreatitis. Eur J Radiol. 2002 Sep;43(3):219-28. [CrossRef]

- Stamatakos M, Stefanaki C, Kontzoglou K, Stergiopoulos S, Giannopoulos G, Safioleas M. Walled-off pancreatic necrosis. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG. 2010 Apr 4;16(14):1707. [CrossRef]

- Foster BR, Jensen KK, Bakis G, Shaaban AM, Coakley FV. Revised Atlanta Classification for Acute Pancreatitis: A Pictorial Essay. Radiographics. 2016 May-Jun;36(3):675-87. [CrossRef]

- Bugiantella W, Rondelli F, Boni M, Stella P, Polistena A, Sanguinetti A, Avenia N. Necrotizing pancreatitis: A review of the interventions. International journal of surgery. 2016 Apr 1;28:S163-71. [CrossRef]

- Zhao K, Adam SZ, Keswani RN, Horowitz JM, Miller FH. Acute pancreatitis: revised Atlanta classification and the role of cross-sectional imaging. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015 Jul;205(1):W32-41. [CrossRef]

- Türkvatan A, Erden A, Türkoğlu MA, Seçil MU, Yüce G. Imaging of acute pancreatitis and its complications. Part 2: complications of acute pancreatitis. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging. 2015 Feb 1;96(2):161-9. [CrossRef]

- Sion MK, Davis KA. Step-up approach for the management of pancreatic necrosis: a review of the literature. Trauma surgery & acute care open. 2019 May 1;4(1):e000308. [CrossRef]

- Caraiani C, Yi D, Petresc B, Dietrich C. Indications for abdominal imaging: When and what to choose?. Journal of ultrasonography. 2020 Apr 1;20(80):43-54. [CrossRef]

- Leite NP, Pereira JM, Cunha R, Pinto P, Sirlin C. CT evaluation of appendicitis and its complications: imaging techniques and key diagnostic findings. InPresented at the 2004 Dec 6. [CrossRef]

- Tao SM, Wichmann JL, Schoepf UJ, Fuller SR, Lu GM, Zhang LJ. Contrast-induced nephropathy in CT: incidence, risk factors and strategies for prevention. European radiology. 2016 Sep;26:3310-8. [CrossRef]

- Xiao B, Zhang XM. Magnetic resonance imaging for acute pancreatitis. World Journal of Radiology. 2010 Aug 8;2(8):298. [CrossRef]

| 0 | Diverticuli ± colonic wall thickening |

| Ia | Colonic wall thickening with pericolic soft tissue changes |

| Ib | Ia changes + pericolic or mesocolic abscess. |

| II | Ia changes + distant abscess (generally deep in the pelvis or interloop regions) |

| III | Free gas associated with localised or generalised ascites and possible peritoneal wallthickening |

| IV | Same findings as III |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).