Submitted:

26 December 2023

Posted:

27 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farheen S.; Agrawal S.; Zubair S.; Agrawal A.; Jamal F.; Altaf I.; et al.. Patho-physiology of aging and immune-senescence: possible correlates with comorbidity and mortality in middle-aged and old COVID-19 patients. Front. Aging. 2021, 2, 748591. [CrossRef]

- Fu Y. W.; Xu H. S.; Liu S. J.. COVID-19 and neurodegenerative diseases. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol Sci. 2022, 26, 4535–4544. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y; Jaber VR; Lukiw WJ. SARS-CoV-2, long COVID, prion disease and neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:1002770. [CrossRef]

- McGrath A; Pai H; Clack A. Rapid progression of probable Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with concomitant COVID-19 infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2023 1;16(11):e254402. [CrossRef]

- Ciolac D.; Racila R.; Duarte C.; Vasilieva M.; Manea D.; Gorincioi N. et al.. Clinical and radiological deterioration in a case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease following SARS-CoV-2 Infection: hints to accelerated age-dependent neurodegeneration. Biomedicines. 2021, 9, 1730. 10. [CrossRef]

- Koc HC, Xiao J, Liu W, Li Y, Chen G. Long COVID and its Management. Int J Biol Sci. 2022, 11;18(12):4768-4780. [CrossRef]

- Minikel E.V., Vallabh S.M., Lek M.et al. Quantifying prion disease penetrance using large population control cohorts. Sci Transl Med. 2016; 8: 322ra9. [CrossRef]

- Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S. et al.Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015; 17: 405-424. [CrossRef]

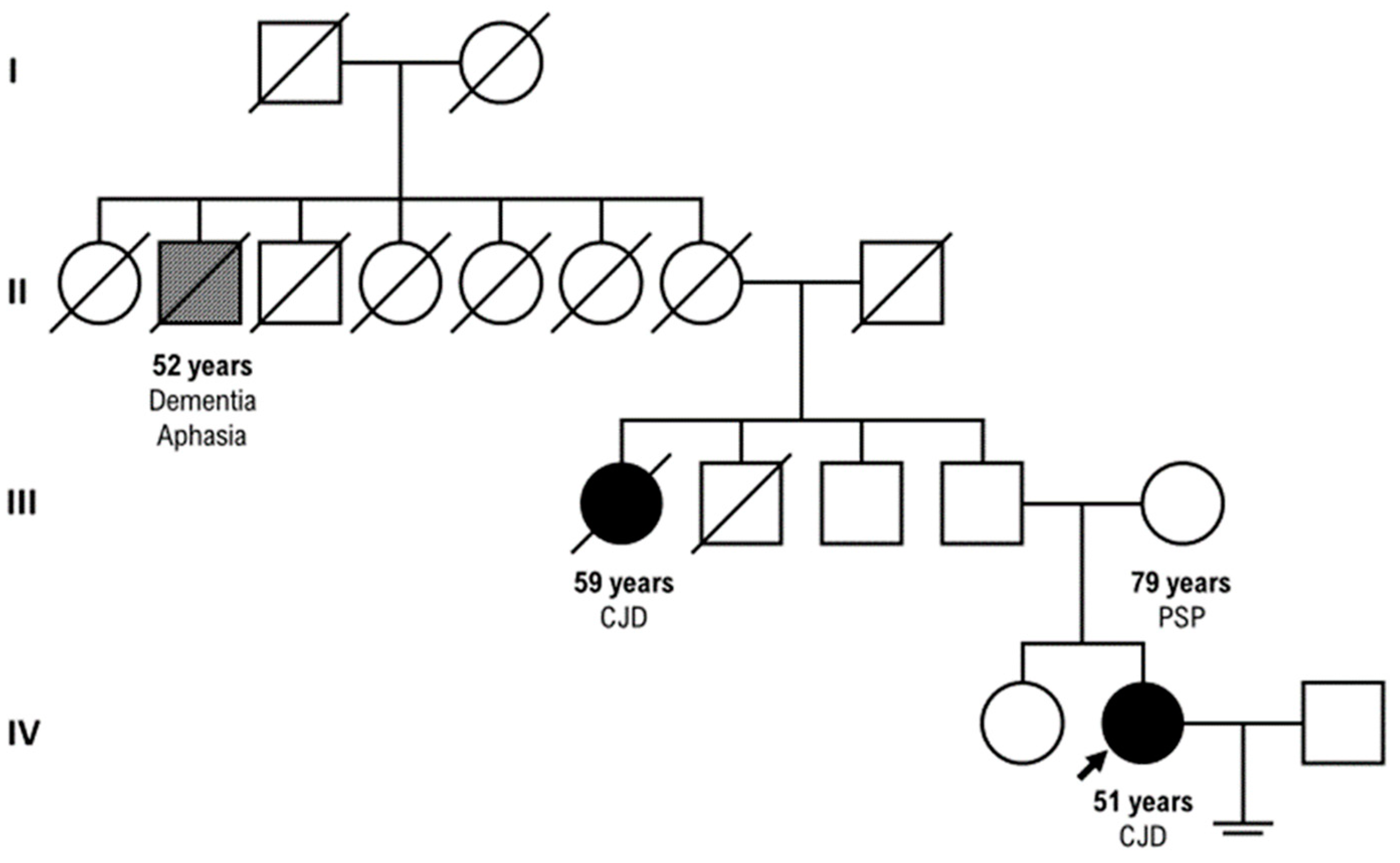

- Ladogana A; Gabor G; Kovacs, Chapter 13 - Genetic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease,Editor(s): Maurizio Pocchiari, Jean Manson,Handbook of Clinical Neurology,Elsevier,Volume 153,2018,Pages 219-242,ISSN 0072-9752,ISBN 9780444639455.

- Won SY; Kim YC; Jeong BH; Elevated E200K Somatic Mutation of the Prion Protein Gene (PRNP) in the Brain Tissues of Patients with Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD). Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 2;24(19):14831. [CrossRef]

- Watson N; Brandel JP; Green A; Hermann P; Ladogana A;Lindsay T; Mackenzie J; Pocchiari M; Smith C; Zerr I; Pal S. The importance of ongoing international surveillance for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(6):362-379. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z; McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 7;323(13):1239-1242. [CrossRef]

- Guedes BF. NeuroCOVID-19: a critical review. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2022;80(5 Suppl 1):281-289. [CrossRef]

- Frontera JA; Thorpe LE; Simon NM; de Havenon A; Yaghi S; Sabadia SB; Yang D; Lewis A; Melmed K; Balcer LJ; Wisniewski T; Galetta SL. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 symptom phenotypes and therapeutic strategies: A prospective, observational study. PLoS One. 2022 29;17(9):e0275274. [CrossRef]

- Pogue A. I.; Lukiw W. J.. microRNA-146a-5p, neurotropic viral infection and prion disease (PrD). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9198. [CrossRef]

- Young M. J.; O'Hare M.; Matiello M.; Schmahmann J. D.. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in a man with COVID-19: SARS-CoV-2-accelerated neurodegeneration? Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 601–603. [CrossRef]

- Lukiw WJ; Jaber VR; Pogue AI; Zhao Y. SARS-CoV-2 Invasion and Pathological Links to Prion Disease. Biomolecules. 2022 7;12(9):1253. [CrossRef]

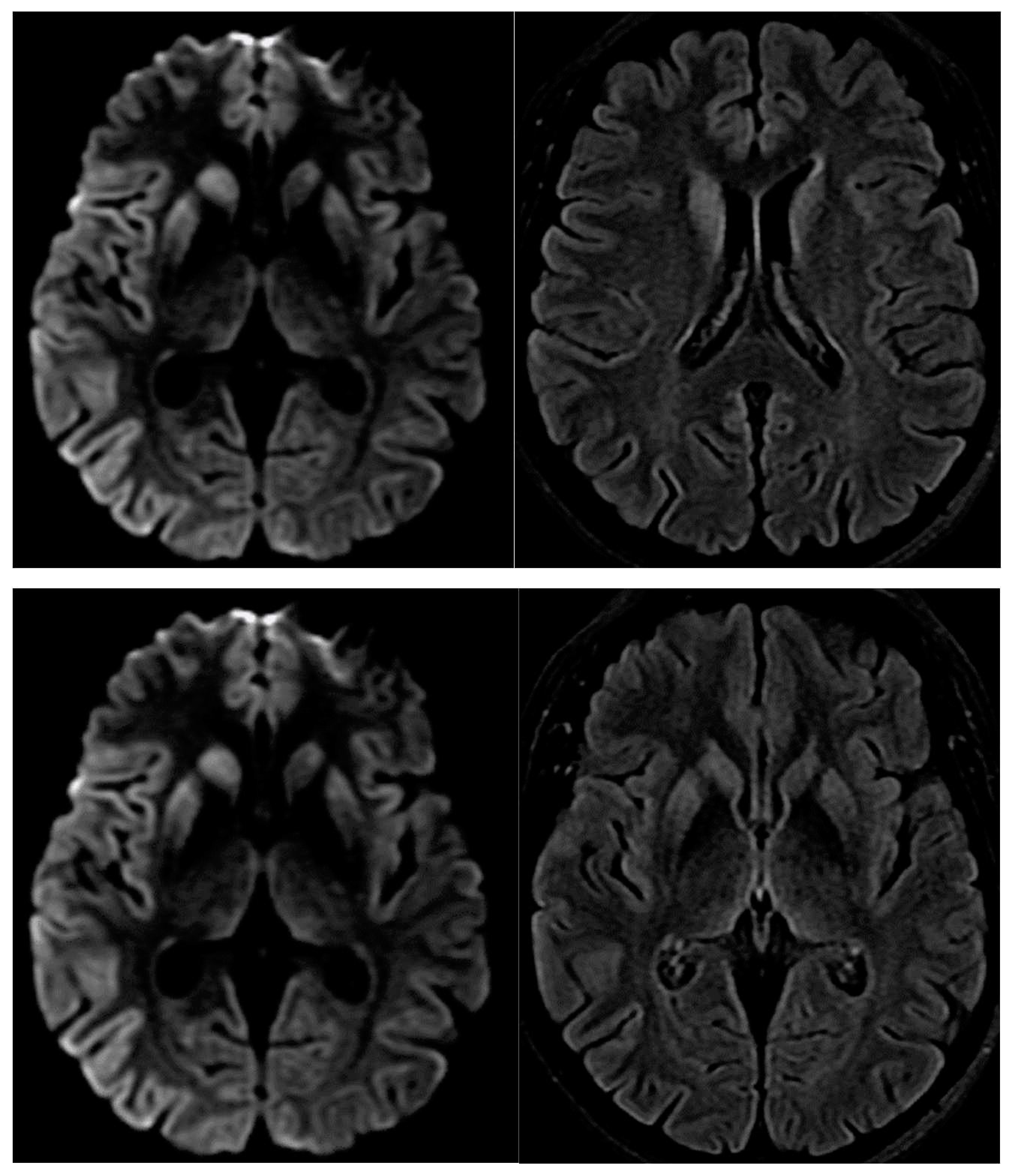

- Fulbright RK, Kingsley PB, Guo X, Hoffmann C, Kahana E, Chapman JC, Prohovnik I. The imaging appearance of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease caused by the E200K mutation. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24(9):1121-9. [CrossRef]

- Tetz G.; Tetz V. Prion-like domains in spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 differ across its variants and enable changes in affinity to ACE2. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 280. [CrossRef]

- Goldman JS; Vallabh SM. Genetic counseling for prion disease: Updates and best practices, Genetics in Medicine, Volume 24, Issue 10, 2022, Pages 1993-2003, ISSN 1098-3600. [CrossRef]

- Takada L.T.; Kim M.O., Cleveland R.W. et al. Genetic prion disease: experience of a rapidly progressive dementia center in the United States and a review of the literature Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet, 2017, 174 (1), pp. 36-69. [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmi A.M., Ray B., Tuladhar S., Bhat A., Paneyala S., Patteswari D., Sakharkar M.K., Hamdan H., Ojcius D.M., Bolla S.R., et al. Does COVID-19 contribute to development of neurological disease? Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2021;9:48–58. [CrossRef]

- Samuel J. Ahmad, Chaim M. Feigen, Juan P. Vazquez, Andrew J. Kobets, David J. Altschul. Neurological Sequelae of COVID-19. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 21(3), 77. [CrossRef]

- Hermann P, Böhnke J, Bunck T, Goebel S, Jaeger VK, Karch A, Zerr I. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 incidence and immunisation rates on sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease incidence. Neuroepidemiology. 2023 Dec 12.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).