Submitted:

21 December 2023

Posted:

22 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

-

a. Subordination: e.g., taxi driver, brain deathb. Modification: e.g., ghostwriter, blackboardc. Coordination: e.g., singer-songwriter, mind-brain

- (2)

-

a. singer-songwriter‘someone who is a singer and songwriter’b. actor-author‘someone who is an actor and author’

- (3)

-

a. mind-brain‘the philosophical and physiological aspects of cognitive processesconsidered as a causally interrelated entity’ <Philosophy>b. Austro-Hungary, Austria-Hungary‘the dual monarchy established in 1867 by the Austrian emperor Franz Josef, according to which Austria and Hungary became autonomous states under a common sovereign.’

2. Framework

2.1. Dvandva from a semasiological perspective

- (4)

-

a. oya-ko Additiveparent child‘parent and child’b. te-asihand foot‘hands and feet, the limbs’c. me-hanaeye nose‘eyes and nose’d. dan=zyoman woman‘man and woman’e. huu=huhusband wife‘man and wife’f. zi=mokuear eye‘eyes and ears; one’s attention or notice’

- (5)

-

a. zen-aku Exocentricvirtue vice‘virtue and vice, good and evil’b. yosi-asigood bad‘good and/or bad, right and/or wrong, merits and demerits’c. ze=hiright wrong‘right and/or wrong, pluses and minuses, pros and cons’d. sin=kyuunew old‘the old and the new, old or new’

- (6)

-

a. kusa-ki Co-hyponymicgrass tree‘plants, vegetation’b. gyo=kaifish shellfish‘fish and shellfish’c. tyoo=zyuubird beast‘birds and animals, wildlife’

- (7)

-

a. sugata-katati Co-synonymicfigure shape‘outward appearance’b. kai=gapicture=picture‘a picture; pictorial arts’

2.2. Dvandva from an onomasiological perspective

- (8)

-

a. a pair of {shoes/socks/earrings/gloves...} cf. a shoeb. a pair of {glasses/scissors/trousers...} cf. *a glass

- [B]: This feature stands for “Bounded.” It signals the relevance of intrinsic spatial or temporal boundaries in a situation or substance/thing/essence. If the feature [B] is absent, the item may be ontologically bounded or not, but its boundaries are conceptually and/or linguistically irrelevant. If the item bears the feature [+B], it is limited spatially or temporally. If it is [−B], it is without intrinsic limits in time or space.

- [CI]: This feature stands for “Composed of Individuals.” The feature [CI] signals the relevance of spatial or temporal units implied in the meaning of a lexical item. If an item is [+CI], it is conceived of as being composed of separable similar internal units. If an item is [−CI], then it denotes something which is spatially or temporally homogeneous or internally undifferentiated.

- (9)

-

a. hitokumi no oya-koone-group gen parent-child‘parents and children as one group’b. hutakumi no oya-kotwo-group gen parent-child‘two groups of parents and children’c. hyakkumi no oya-koone-hundred-group gen parent-child‘100 groups of parents and children’

- (10)

-

a. Taroo to Hanako ga {hure-atta/warai-atta}.and nom touch-meet.pst/smile-meet.pst‘Taro and Hanako {touched each other/smiled at each other}.’b. *Taroo ga {hure-atta/warai-atta}.nom touch-meet.pst smile-meet.pst

- (11)

-

a. Hitokumi no oya=ko ga {hure-atta/warai-atta}.one-group gen parent-child nom touch-meet.pst smile-meet.pst‘A parent and her child {touched each other/smiled at each other}.’b. Hanako no te-asi ga hure-atta.gen hand-foot nom touch-meet.pst‘Hanako’s hand and foot touched each other.’

- (12)

-

a. hastyaśvau Sanskritelephant (hastin-)-horse (aśva-).du‘elephant and horse’b. hastyaśvāḥelephant-horse. pl‘elephants and horses’

- (13)

-

a. jinek-o-peδa Modern Greekwoman-CM-child.pl‘women and children’b. maxer-o-pirunaknife-CM-fork.pl‘cutlery’c. ader-o-sikotaintestine-CM-liver.pl‘intestines and livers’

- (14)

-

a. t’et’a.t-ava.t Mordvinfather.pl-mother.pl‘parents’b. ponks.t-panar.ttrousers.pl-short.pl‘clothing, clothes’

- (15)

-

a. Anglo-Saxons are Angles plus Saxons.b. *An Anglo-Saxon is an Angle plus a Saxon.

3. Data

3.1. Pattern A

- (16)

-

a. Subordination (Complementation)mi-otos(u)look fail‘to fail to see, to overlook’Subordination or modification (resultative)tataki-war(u)hit break‘to break (something) by hitting it’b. Modification (manner)tobi-okir(u)jump get up‘to get up in a jumping motion’moti-yor(u)have approach‘to crawl towards’c. Coordinationsee (17)

- (17)

-

a. naki-sakeb(u) co-synonymic/nonrepetitive durativecry scream‘to cry and scream’naki-wamek(u)cry scream‘to cry and scream’ukare-sawag(u)be.excited be.noisy‘to be noisy’hikari-kagayak(u)shine shine‘to shine’omoi-egak(u)think picture‘to imagine’nageki-kanasim(u)lament be.sad‘to mourn’tae-sinob(u)bear endure‘to bear’koi-sitawlong for-adore‘to long for, to miss deeply’imi-kirawavoid hate‘to detest’b. odoroki-akire(ru) co-synonymic/punctualbe.surprised be.appalled‘to be surprised’nare-sitasim(u)get used to get friendly‘to get used to and like’ake-kure(ru) reversive(day) begin (day) end‘to spend all one’s time doing’

3.2. Pattern B

- (18)

-

verb zero-form + verb zero forma. uri-kai (*uri-kaw) converse/repetitive durativesell buy‘to sell and buy’yari-tori (*yari-tor(u))give take‘to exchange (things, information), to talk, to discuss’yari-morai (*yari-moraw)give receive‘to give and take’uke-kotae (??uke-kotae(ru))receive reply‘to receive and reply’uke-watasi (uke-watas(u))receive give‘to receive and give’b. iki-ki (*iki-kur(u)) reversive/repetitive durativecome go‘to come and go’agari-sagari (*agari-saga(ru))ascend descend‘to ascend and descend’nobori-ori (*nobori-ori(ru))rise fall‘to rise and fall’de-iri (*de-ir(u))exit enter‘to enter and exit’dasi-ire (*dasi-ire(ru))put.in take.out‘to put in and take out’ake-sime (*ake-sime(ru))open close‘to open and close’b. ne-tomari (*ne-tomar(u)) co-hyponymic/ repetitive durativesleep stay‘to stay at, to stay with’mi-kiki (*mi-kik(u))see hear‘to experience’nomi-kui (*nomi-ku(u))drink eat‘to eat and drink’yomi-kaki (*yomi-kak(u))read write‘to read and write’

- (19)

-

Present tense inflection of the double infinitive compounda. yomi-kaki → *yomi-kaku vs. yomi-kaki sururead write read write.pres read write do.pres‘to read and write’b. iki-ki → *iki-kuru vs. iki-ki surucome go come go.pres come go do.pres‘to come and go’c. ne-tomari → *ne-tomaru vs. ne-tomari surusleep stay sleep stay.pres sleep stay do.pres‘to sleep and stay’

- (20)

-

a. Subordinationii-yodomi cf. ii-yodom(u)say hesitate say hesitate(.pres)‘to hesitate to say’tori-kesi cf. tori-kes(u)take remove take remove(.pres)‘to take back’obore-zini cf. obore-sin(u)drown die drown die(.pres)‘to die by drowning’b. Modificationsusuri-naki cf. susuri-nak(u)sniffle cry sniffle cry(.pres)‘to sob’tati-yomi cf. *tati-yom(u)stand read stand read(.pres)‘to read standing up, to browse in a bookstore’d. Coordinationyomi-kaki cf. *yomi-kak(u) = (18a)read write read write(.pres)‘to read and write’

3.3. Treatment in the literature

4. Discussion

4.1. Testing the prediction

I propose that the feature [B] to be used to encode the distinction between temporally punctual situations and temporally durative ones. [+B] items will be those which have no linguistically significant duration, for example, explode, jump, flash, name. [−B] items will be those which have linguistically significant duration, for example, descend, walk, draw, eat, build, push. (Lieber 2004: 137)

Plural nouns denote multiple individuals of the same kind, nonplural nouns single individuals or mass substances. I would like to suggest that the corresponding lexical distinction in situations is one of iterativity vs. homogeneity. Some verbs denote events which by their very nature imply repeated actions of the same sort, for example, totter, wiggle, pummel, or giggle. By definition, to totter or to wiggle is to produce repeated motions of a certain sort, to pummel is to produce repeated blows, and to giggle to emit repeated small bursts of laughter. Such verbs, I would say, are lexically [+CI]. The vast majority of other verbs would be [−CI]. Verbs such as walk or laugh or build, although perhaps not implying perfectly homogeneous events, are not composed of multiple, repeated, relatively identical actions. (Lieber 2004: 138-139)

- (21)

-

a. Taro to Hanako wa sannen kan meeru de yari-tori sita Converseand top three year for e-mail by give-take do.pst‘Taro and Hanako exchanged e-mails for three years.’b. Taro wa sannen kan ie to sono byooin o iki-ki sita Reversivetop three year for house and the hospital acc go-come do.pst‘Taro went back and forth between his house and the hospital for three years.’c. Hanako wa hito ban zyuu sono mado o ake-sime sita Reversivetop one night through the window acc open-close do.pst‘Hanako opened and closed the window all through the night.’d. Hanako wa natu zyuu oba no ie de ne-tomari sita Co-hyponymictop summer through aunt gen house at sleep-stay do.pst‘Hanako spent the summer at her aunt’s house.’

- (22)

-

a. Taro to Hanako wa takusan syoogaku o yari-tori sita numberand top a lot small sum acc give-take do.pst‘Taro and Hanako exchanged a small amount of money many times.’b. Taro wa ie to sono byooin o takusan iki-ki sitatop house and the hospital acc a lot go-come do.pst‘Taro went back and forth between his house and the hospital many times.’c. Hanako wa sono mado o takusan ake-sime sitatop the window acc a lot open-close do.pst‘Hanako opened and closed the window many times.’d. Hanako wa oba no ie de takusan ne-tomari sitatop summer aunt gen house at a lot sleep-stay do.pst‘Hanako stayed at her aunt’s house many times.’

- (23)

-

a. Watasi wa takusan {neta/naita} duration, intensityI top a lot {slept/cried}‘I slept/cried a lot.’b. Kami ga takusan nobita. degreeHair nom a lot grew‘My hair grew a lot.’Kion ga takusan {agatta/sagatta} degreethe temperature nom a lot {rose/fell}‘The temperature rose/fell a lot.’c. Watasi wa takusan {yatta/totta} volume of the themeI top a lot {gave/took}‘I gave/took a lot.’Watasi wa takusan {yonda/kaita}.I top a lot {read/wrote}‘I read/wrote a lot.’

- (24)

-

a. Taro to Hanako ga ikkai agari-sagari sita.and nom once ascend-descend do.pst(i) ‘Taro and Hanako ascended and descended together.’(ii) ‘Taro ascended and Hanako descended. ‘ or‘Taro descended and Hanako ascended.’Yamada huuhu ga ikkai sono omoi mado o ake-sime sitahusband-wife nom once the heavy window open-close do.pst‘Mr. & Mrs. Yamada opened and closed the heavy window together.’‘Mr. Yamada opened the heavy window and Mrs. Yamada closed it.’ or ‘Mrs. Yamada opened the heavy window and Mr. Yamada closed it.’

- (25)

-

a. Taro to Hanako wa niziikan naki-wameita Nonrepetitive durativeand top two hour cry-scream.pst(i) ‘Taro and Hanako cried and screamed for two hours.’(ii) *’Taro cried and Hanako screamed for two hours, respectively.’b. Taro to Hanako wa (*nizikan) sono sensei ni nare-sitasinda Punctualand top (two hours) the teacher dat get used-grow intimate.pst(i) ‘Taro and Hanako got to know and like the teacher.’(ii) *’Taro got used to the teacher and Hanako became intimate with her, respectively.’

- (26)

-

a. Taroo wa takusan naki-sakenda duration or intensity, *numbertop a lot cry-scream.pst‘Taro cried and screamed a lot.’b. Watasi wa kanoosei o takusan omoi-egaita. volume of the theme, *numberI top possibility acc a lot think picture.pst‘I imagined a lot of possibilities.’

4.2. Treatment of Pattern A

| Kanji representation | Native pronunciation | Sino-Japanese pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| 売+買 | (18a) uri-kai (suru) | bai=bai (suru) |

| 授+受、受+授 | (18a) yari-tori, yari-morai | zyu=zyu |

| 往+来 | (18b) iki-ki | oo=rai |

| 上+下 | (18b) agari-sagari | zyoo=ge |

| 出+入 | (18b) de-iri, dasi-ire | syutu=nyuu |

| 開+閉 | (18b) ake-sime | kai=hei |

| 見+聞 | (18c) mi-kiki | ken=bun |

| 飲+食 | (18c) nomi-kui | in=syoku |

4.3. Pattern A as the verbal counterpart of appositive coordinate compounding

- (27)

-

a. I met a singer-songwriter.b. We hired three singer-songwriters.

- (28)

-

a. John is a poet-painter. Englishb. John est (un) poète-peintre. French

- (29)

-

a. Sue and Ken are poet-painters. Englishb. Sue et Ken sont (des) poètes-peintres. French

- (30)

- Principle of Coindexation

- (31)

-

a. naki-sakeb(u) intransitive + intransitivecry scream‘to cry and scream’naki-wamek(u)cry scream‘to cry and scream’ukare-sawag(u)be.excited be.noisy‘to be noisy’hikari-kagayak(u)shine shine‘to shine’ake-kure(ru)(day) begin (day) end‘to spend all one’s time doing’b. omoi-egak(u) transitive + transitivethink picture‘to imagine’nageki-kanasim(u)lament be.sad‘to mourn’tae-sinob(u)bear endure‘to bear’koi-sitawlong for-adore‘to long for, to miss deeply’imi-kirawavoid hate‘to abhor’odoroki-akirer(u)be.surprised be.appalled‘to be surprised’nare-sitasim(u)get used to get friendly‘to get used to and like’

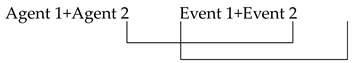

- appositive coordinate compound (for the predicative use)9

-

poet painter poet-painter[+material (x)] + [+material, +dynamic (i)] → [+material, +dynamic (x=i)]Body Body synthesized Body

- intransitive Pattern A compound

-

naki- sakeb- naki-sakeb-[+dynamic (x)] + [+dynamic (i)] → [+dynamic (x=i)]Body Body synthesized Body

- (32)

- Hearing the play in OP [Original Pronunciation], according to Ben, offered a new auditory experience of an old play that neatly complemented the ‘old-new’ interpretation provided by Richter’s reworking of Vivaldi.

- transitive Pattern A compounding

-

omoi- egak- omoi-egak-[+dynamic (x, y)] + [+dynamic (i, j)] → [+dynamic (x=i, y=j)]Body Body synthesized Body

5. Conclusions

List of abbreviations

-

A: adjectiveacc: accusative[+B]: a semantic feature that stands for “bounded” in the LSF. When a word has this feature, it is bounded in space or time.[+CI]: a semantic feature that stands for “composed of individuals” in the LSF. When a word has this feature, it is conceived of as being composed of separable, similar internal units.CM: compounding markerCOORD: coordinate compounding or coordinate compoundsdat: dativedu: dualgen: genitiveLSF: Lexical Semantic FrameworkMOD: modificational compounding or modificational compoundsN: nounnom: nominativepst: past tensepl: pluralprs: present tenseR argument: referential argumentSUB: subordinate compounding or subordinate compoundstop: topicV: verb

| 1 | In Scalise and Bisetto’s (2009) model, the modificational class is called “attributive-appositive,” where “appositives” are separate from the type in (2) and refer to compounds such as snailmail, swordfish, and mushroom cloud. While we do not endorse this usage, the confusion itself testifies the existence of the said continuum. |

| 2 | Pace the following suggestion: “It should be clear though that the distinction in coordinative [= dvandva or co-compound] and appositive compounds applies only to [NN] compounds. For [AA] and [VV] formations, this distinction is meaningless since their semantics do not imply a referent.” (Ralli 2013: 161) |

| 3 |

Opposites refer to pairs of semantically incompatible binary words and divide into four main subtypes: complementaries (such as dead : alive, true : false, male : female), antonyms (such as long : short, hot : cold, good : bad), reversives (such as up : down, rise : fall, advance : retreat), and converses (such as above : below, lend : borrow, husband : wife) (Cruse 2011: 153-161). |

| 4 | For instance, gyo=kai ‘fish and shellfish’ (6b) is such an exception when written as 魚貝 but not when written as 魚介. According to an authoritative dictionary, the mixed reading emerged as a reanalysis of the original [bound (魚 gyo) + bound (介 kai)] structure. |

| 5 | The compound analysis of (19a) [yomi-kaki suru] (for example) is refuted in Yuhara (in press). His main argument that such suru combinations consist of two separate words is consistent with our periphrastic inflection analysis. |

| 6 | The formal difference led Ralli (2013) to conclude that the appositive construction in Modern Greek is outside morphological compounding. See also Koliopoulou (2014). |

| 7 | The example ake-kure(ru) in (17b) is based on a pair of reversive verbs denoting the rising and falling of the sun. Although the process of the semantic extension underlying its meaning of ‘spend all day doing something’ are not entirely clear to us, the compound does not allow a consecutive serial action reading or a one-to-one distributive reading. |

| 8 | This is a topic of much debate in the literature on VV compounding (e.g., Kageyama 1993, Fukushima 2005, in press, Yumoto 2005, among others, for Japanese VV compounding in the [X-i/e Y] form; Packard 2000: 250-258 for Mandarin Chinese VV compounding). |

| 9 | Discussed in Lieber (2009, 2016b) are attributive compounds in the argumental use where the components’ R(eferential) arguments get coindexed. In the suggested analysis below, we assume that nominal predicates possess a subject argument while lacking an R argument. |

References

- Acquaviva, Paolo. 2008. Lexical plurals: A morphosemantic approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Arcodia, Giorgio, F., Nichola Grandi, and Bernhard Wälchli. 2010. Coordination in compounding. In Cross-disciplinary Issues in Compounding. Edited by Sergio Scalise and Irene Vogel. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 177-197.

- Aronoff, Mark. 2023. Three ways to look at morphological rivalry. Word Structure 16 (1): 49-62. [CrossRef]

- Bagasheva, Alexandra. 2015. On the classification of compound verbs. On-line proceedings of the Eighth Mediterranean Morphology Meeting (MMM8). Edited by Angela Ralli, Geert Booij, Sergio Scalise, and Athanasios Karasimos, pp.41-55.

- Bauer, Laurie. 2008. Dvandvas. Word Structure 1: 1-20.

- Bauer, Laurie. 2010a. Co-compounds in Germanic. Journal of Germanic Languages 22 (3): 201-219. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Laurie. 2010b. The typology of exocentric compounds. In Cross-disciplinary issues in compounding. Edited by Sergio Scalise and Irene Vogel. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 167–175.

- Bauer, Laurie. 2017. Compounds and compounding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bauer, Laurie. 2022. Exocentricity yet again: A response to Nóbrega and Panagiotidis. Word Structure 15 (2): 138-147. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Laurie, Rochelle Lieber, and Ingo Plag. 2013. The Oxford Reference Guide to English Morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Corbett, Greville. 2000. Number. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ceccagno, Antonella, and Bianca Basciano. 2009. Sino-Tibetan: Mandarin Chinese. In The Oxford handbook of compounding. Edited by Rochelle Lieber and Pavol Štekauer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 478-490.

- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Cruse, Alan. 2011. Meaning in language: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics, 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fukushima, Kazuhiko. 2005. Lexical V-V compounds in Japanese: Lexicon vs. syntax. Language 81 (3): 568-612. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, Kazuhiko. In press. Competition of lexicon vs. pragmatics in word formation: Japanese lexical V-V compounds and argument synthesis. In Competition in Word-Formation. Edited by Alexandra Bagasheva, Akiko Nagano, and Vincent Renner. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Gardelle, Laure. 2019. Semantic plurality: English collective nouns and other ways of denoting pluralities of entities. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- ten Hacken, Pius. 1994. Defining morphology: A principled approach to determining the boundaries of compounding, derivation, and inflection. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag.

- Harris, Alice C. 2017. Multiple exponence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hoeksema, Jack. 1988. The semantics of non-Boolean ‘AND.’ Journal of Semantics 6: 19-40. [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey K. Pullum. Eds. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kageyama, Taro. 1993. Bunpoo to gokeisei [Grammar and word-formation]. Tokyo: Hituzi.

- Kageyama, Taro. 2009. Isolate: Japanese. In The Oxford handbook of compounding. Edited by Rochelle Lieber and Pavol Štekauer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 512-526.

- Kiparsky, Paul. 2009. Verbal co-compounds and subcompounds in Greek. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 57, 187-195.

- Kiparsky, Paul. 2010. Dvandvas, blocking, and the associative: The bumpy ride from phrase to word. Language 86 (2): 302-331. [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, Hideki, and Satoshi Uehara. 2016. Lexical categories. In Handbook of Japanese lexicon and word formation. Edited by Taro Kageyama and Hideki Kishimoto. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 51-91.

- Koliopoulou, Maria. 2014. How close to syntax are compounds? Evidence from the linking element in German and Modern Greek compounds. Rivista di Linguistica 26 (2): 51-70.

- Kopaczyk, Joanna, and Hans Sauer. 2017. Defining and exploring binomials. In Binomials in the History of English. Edited by Joanna Kopaczyk and Hans Sauer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-23.

- Lauwers, Peter and Marie Lammert. 2016. New perspectives on lexical plurals. Lingvisticæ Investigationes 39 (2): 207-216. [CrossRef]

- Lieber, Rochelle. 2004. Morphology and lexical Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lieber, Rochelle. 2009. A lexical semantic approach to compounding. In The Oxford Handbook of Compounding. Edited by Rochelle Lieber and Pavol Štekauer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 78-104.

- Lieber, Rochelle. 2016a. English nouns: The ecology of nominalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lieber, Rochelle. 2016b. Compounding in the lexical semantic framework. In The semantics of compounding. Edited by Pius ten Hacken. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.38-53.

- Lieber, Rochelle, and Pavol Štekauer. eds. 2009. The Oxford handbook of compounding. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Manolessou, Io, and Symeon Tsolakidis. 2009. Greek coordinated compounds: Synchrony and diachrony. Patras Working Papers in Linguistics 1, 23-39.

- Masini, Francesca, and Anna M. Thornton. 2008. Italian VeV lexical constructions. On-line proceedings of the sixth Mediterranean Morphology Meeting (MMM6). Edited by Angela Ralli, Geert Booij, Sergio Scalise, and Athanasios Karasimos, pp.149-189.

- Masini, Francesca, Simone Mattiola, and Steve Pepper. 2023. Exploring complex lexemes cross-linguistically. Binominal lexemes in cross-linguistic perspective: Towards a typology of complex lexemes. Edited by Steve Pepper, Francesca Masini, and Simone Mattiola. De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-20. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Yo. 1996. Complex predicates in Japanese: A syntactic and semantic study of the notion ‘word.’ Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

- Nagano, Akiko, and Masaharu Shimada. 2014. Morphological theory and orthography: Kanji as a representation of lexemes. Journal of Linguistics 50 (2): 323-364. [CrossRef]

- Naya, Ryohei, and Takashi Ishida. 2021. Double endocentricity and constituent ordering of English copulative compounds. In Data Science in Collaboration 4. Edited by Yuichi Ono and Masaharu Shimada. Tsukuba: University of Tsukuba, pp. 49-57.

- Nicholas, Nick, and Brian D. Joseph. 2009. Verbal dvandvas in Modern Greek. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 57: 171-185.

- Niinuma, Fumikazu. 2015. The syntax of dvandva VV compounds in Japanese. The Journal of Morioka University 32: 53-68.

- Nóbrega, Vitor A., and Phoevos Panagiotidis. 2020. Headedness and exocentric compounding. Word Structure 13 (2): 211-249. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Susan. 2001. Copulative compounds: A closer look at the interface between syntax and morphology. In Yearbook of Morphology 2000. Edited by Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, pp. 279-320.

- Packard, Jerome L. 2000. The morphology of Chinese: A linguistic and cognitive approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pepper, Steve. 2016. Windmills, Nizaa and the typology of binominal compounds. In Word-Formation across Languages. Edited by Lívia Körtvélyessy, Pavol Štekauer, and Salvador Valera. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp.281-310.

- Ralli, Angela. 2013. Compounding in Modern Greek. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Ralli, Angela. 2019. Coordination in compounds. Oxford Research Encyclopedia. https://oxfordre.com/linguistics.

- Renner, Vincent. 2008. On the semantics of English coordinate compounds. English Studies 89 (5): 606-613. [CrossRef]

- Roy, Isabelle. 2013. Nonverbal predication: Copular sentences and the syntax-semantics interface. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scalise, Sergio, and Antonietta Bisetto. 2009. The classification of compounds. In The Oxford Handbook of Compounding. Edited by Rochelle Lieber and Pavol Štekauer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 33-53.

- Scalise, Sergio, Antonio Fábregas, and Francesca Forza. 2009. Exocentricity in compounding. Gengo Kenkyu 135: 49-84.

- Shimada, Masaharu. 2013. Coordinated compounds: Comparison between English and Japanese. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 10: 77-96.

- Spencer, Andrew. 2019. Canonical compounds. In Morphological perspectives: Papers in honour of Greville G. Corbett. Edited by Matthew Baerman, Oliver Bond, and Andrew Hippisley. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp.31-64.

- Tanaka, Hideki. 2015. Eigo to nihongo ni okeru suuryoosihyoogen to kankeisetu no kaisyaku ni kansuru kizyututeki rironteki kenkyuu [A descriptive-theoretical study on the semantics of quantifiers and relative clauses in English and Japanese]. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

- Tsujimura, Natsuko. 2014. An introduction to Japanese linguistics, 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

- Ueno, Yoshio. 2016. Gendainihongo no bunpookoozoo: keitaironhen [The grammatical structure of Modern Japanese: Morphology]. Tokyo: Waseda University Press.

- Wälchli, Bernhard. 2005. Co-compounds and natural coordination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Whitney, William Dwight. 1879. Sanskrit grammar. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (Reprinted 1962).

- Williams, Edwin. 1981. On the notions ‘lexically related’ and ‘head of a word.’ Linguistic Inquiry 12: 245-274.

- Yonekura, Hiroshi, Akiko Nagano, and Masaharu Shimada. 2023. Eigo to nihongo ni okeru tooihukugoogo [Coordinate compounds in English and in Japanese]. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

- Yuhara, Ichiro. In press. Revisiting Poser’s (1992) “Blocking of phrasal constructions by lexical items” from the perspective of the economy of language use principle. In Competition in Word-Formation. Edited by Alexandra Bagasheva, Akiko Nagano, and Vincent Renner. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Yumoto, Yoko. 2005. Hukugoodoosi haseidoosi no imi to toogo [The semantics and syntax of compounded and derived verbs]. Tokyo: Hituzi.

| Semantic features | Examples in N | Examples in V |

|---|---|---|

| [+B, −CI] | person, fact | explode, name |

| [−B, −CI] | furniture, water | descend, walk |

| [+B, +CI] | committee, herd | <logically impossible> |

| [−B, +CI] | cattle, sheep | totter, pummel, wiggle1 |

| Pattern A | Pattern B | |

|---|---|---|

| Formal schema | X-i/e Y 1 | X-i/e Y-i/e |

| Inflection | word internal | periphrastic |

| Syntactic category | verb | nonconjugational verb |

| Accent pattern | Same as the subordinate and modificational types | Same as the NN dvandva |

| Semantic relation | co-synonymic, reversive | reversive, converse, co-hyponymic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).