Submitted:

21 December 2023

Posted:

22 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Application of SWOT for dental students

2.2. Sample of the study

2.3. Ethics Statement

2.4. Methods

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Appendix A

7. Appendix B

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stoller, JK. A Perspective on the Educational "SWOT" of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Chest. 2021, 159(2):743-748. Epub 2020 Sep 18. [CrossRef]

- Benzaghta, M.A.; Elwalda, A.; Mousa, M.M.; Erkan, I.; Rahman, M. SWOT analysis applications: An integrative literature re-view. JGBI 2021, 6(1), 55-73. https://www.doi.org/ 10.5038/2640-6489.6.1.1148.

- Longhurst, G.J; Stone, D.M.; Dulohery, K.; Scully, D.; Campbell, T.; Smith, C.F. Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, Threat (SWOT) Analysis of the Adaptations to Anatomical Education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic. Anat Sci Educ. 2020, 13(3),301-311. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A. SWOT Analysis (or SWOT Matrix) Tool as a Strategic Planning and Management Technique in the Health Care Industry and Its Advantages. J Biomed Sci. 2021, 40(2), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Sit, C.H.P.; Huang, W.Y.J.; Wong, S.H.S.; Wong, M.C.S.; Sum, R.K.W.; Li, V.M.H. Results and SWOT Analysis of the 2022 Hong Kong Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents With Special Educational Needs. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2022, 40(3), 495-503. [CrossRef]

- Willis, D.O. Business Basics for Dentists. 1st ed. Publisher:John Wiley & Sons. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Pires, C. A SWOT Analysis of Pharmacy Students’ Perspectives on e-Learning Based on a Narrative Review. Pharmacy 2023, 11(3), 89. [CrossRef]

- Rattan, R.; Manolescue, G. The business of Dentistry. Quintessence Publishing Co Ltd., London UK, 2002.

- Anthony I. SWOT Self-analysis: Student Assessment and Monitoring. Nurse Educ. 2016, 41(3),138. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Masoura, E.; Devetziadou, M.; Rahiotis, C. Ethical Dilemmas for Dental Students in Greece. Dent J (Basel). 2023a, 11(5),118. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Chrysochoou, G.; Tzanetopoulos, R.; Riza, E. Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece. Sustainability 2023b, 15, 9508. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Leadership and Managerial Skills in Dentistry: Characteristics and Challenges Based on a Preliminary Case Study. Dent J. 2022, 10, 146. [CrossRef]

- Renjith, V.; Yesodharan, R.; Noronha, J.A.; Ladd, E.; George, A. Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research. Int J Prev Med. 2021,12,20.

- Chai, H.H.; Gao, S.S.; Chen, K.J.; Duangthip, D.; Lo, E.C.M.; Chu, C.H. A Concise Review on Qualitative Research in Dentistry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18(3),942. [CrossRef]

- Dalmaijer, E. S.; Nord, C. L.; Astle, D. E. Statistical power for cluster analysis. BMC bioinform 2020, 23(1), 205. [CrossRef]

- Bursac, Z.; Gauss, C.H.; Williams, D.K. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008, 3,17. [CrossRef]

- Heslin P.A. Conceptualizing and Evaluating Career Success. J Organ Behav. 2005, 26(2), 113–136. [CrossRef]

- Amir, T.; Gati, I.; Kleiman, T. Understanding and interpreting career decision-making difficulties. J Career Assess. 2008, 16, 281–309. [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S. E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Holtom, B.C.; Pierotti, A. J. The best laid plans sometimes go askew: Career self-management process, career shocks, and the decision to pursue graduate education. J App Psychol. 2013, 98(1), 169–182. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Z.; Kumar, S.; Padakannaya, P. Well-being and career decision-making difficulties among master’s students: simultaneous multi-equation modeling. Cogent Psychol. 2021, 8(1),1996700. [CrossRef]

- Kossioni, A.E.; Varela,R.; Ekonomu, I.; Lyrakos, G.; Dimoliatis I.D.K. Students’ perceptions of the educational environment in a Greek Dental School, as measured by DREEM. Eur J Dent Edu. 2011, 16, (1), 73-78. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, E. Personal Development Plans for Dentists. The new approach to continuing professional development. Br Dent J. 2004, 196, 60. [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, A.; Jones, R.; Cowpe, J. Clinical skills of a new foundation dentist: the expectations of dental foundation edu-cation supervisors. Br Dent J 2018, 225, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Cowpe, J.; Bullock, A. Clinical skills of a new foundation dentist: the experience of dental foundation educa-tional supervisors. Br Dent J. 2018, 225, 177–186 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Heslin, P.A. Developing career resilience and adaptability. Organ. Dyn. 2016, 45(3), 245-257. [CrossRef]

- Rochat, S. The career decision-making difficulties questionnaire: a case for item-level interpretation. Career Dev. Q. 2019, 67, 205–219. [CrossRef]

- Gati, I.; Levin, N.; Landman-Tal, S. “Decision-making models and career guidance. In: International Handbook of Career Guidance Athanasou, J.A; Van Esbroeck, R. (eds).Publisher: Springer, Dordrecht. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Audiobook ed. Readtrepreneur publ. 2019.

- Schroder, H.S. Mindsets in the clinic: Applying mindset theory to clinical psychology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 83, 101957. [CrossRef]

- Heslin, P.A.; Keating, L.A.; Minbashian, A. How Situational Cues and Mindset Dynamics Shape Personality Effects on Career Outcomes. J. Manage. 2019, 45(5), 2101-2131. [CrossRef]

- Keating LA.; Heslin PA. The Potential Role of Mindsets in Unleashing Employee Engagement. Hum Resour Manage Rev. 2015, 25, 329–341. [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J.L.; Pollack, J.M.; Forsyth, R.B.; Hoyt, C.L.; Babij, A.D.; Thomas, F. N.; Coy, A.E. A Growth Mindset Intervention: Enhancing Students’ Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Career Development. E.T.P. 2019, 44(5),878 -808. [CrossRef]

- Soyoung, B.; Miyoung, K.; Soon-Ho, K. The Relationship Among Undergraduate Students’ Career Anxiety, Choice Goals, and Academic Performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2022, 34(4), 229-244. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.M.; Paganelli, C. Exploration of Mental Readiness for Enhancing Dentistry in an Inter-Professional Climate. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18(13):7038. PMID: 34280975; PMCID: PMC8297289. [CrossRef]

- Sahota, M. From Growth Mindset to Evolutionary Mindset. Leadership. (accessed 16 December 2023 from https://shift314.com/evolutionary-mindset/.

- Ashford, S.J.; Scott DeRue, D. Developing as a Leader: The Power of Mindful Engagement. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41(2), 146–154. [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Tang, M.; Chen, S.; Montgomery, M. L. Effects of a career course on Chinese high school students' career decision-making readiness. Career Dev. Q. 2020, 68, 222–237. [CrossRef]

- Greenbank, P.; Hepworth, S. Improving the career decision-making behaviour of working-class students: Do economic barriers stand in the way? J.Eur. Ind. Train, 2008, 32( 7), 492. [CrossRef]

- Da Graça Kfouri, M.; Moysés, S.T.; Gabardo, M.C.L.; Moysés, SJ. Gender differences in dental students' professional expectations and attitudes: a qualitative study. Br Dent J. 2017, 223(6):441-445. [CrossRef]

- Seibert S.E; Kraimer, M.L.; Liden, R.C.A Social Capital Theory of Career Success. Acad. Manage. J. 2001, 44, 219–237. [CrossRef]

- Esbroeck, R.V.; Tibos, K.I.M.; Zaman, M. A dynamic model of career choice development. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2005, 5, 5–18. [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. Career construction theory and practice In Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work.2nd Brown, S.D.; Len,t R.W. Eds. Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2013, 144-180.

- Saka, N.; Gati, I.; Kelly, K.R. Emotional and personality-related aspects of career-decision-making difficulties. J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 403–424. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.P.; Hou, P.C.; Kronholz, J.F.; Dozier, V.C.; McClain, M.C.; Buzzetta, M.; et al. A content analysis of career development theory, research, and practice. Career Dev. Q. 2014, 62, 290–326. [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [CrossRef]

- Topor, D.R.; Dickey, C.; Stonestreet, L.; Wendt, J.; Woolley, A.; Budson, A. Interprofessional Health Care Education at Aca-demic Medical Centers: Using a SWOT Analysis to Develop and Implement Programming. MedEdPORTAL. 2018, 14:10766. [CrossRef]

- Hayden, S.C.; Osborn, D. S. Impact of worry on career thoughts, career decision state, and cognitive information processing skills. J. Employ. Couns. 2020, 57, 163–177. [CrossRef]

- Levin, N.; Udayar, S.; Lipshits-Braziler, Y.; Gati, I.; Rossier, J. The structure of the career decision-making difficulties ques-tionnaire across 13 countries. J. Career Assess. 2023, 31, 129–148. [CrossRef]

- Griffee, D.T.; Templin, S.A. Goal setting affects task performance. 1997. Accessed on 16 December from ERIC database: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED413782.

- Bandura, A.; Schunk, D. Cultivating competence, self-efficacy and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. J Pers Soc Psycho. 1981, 41(3), 586–598. [CrossRef]

- Heslin P.A. Experiencing Career Success. Organizational Dynamics, 2005, 34(4), 376–390.

- Locke, E. A.; Latham, G.P. A theory of goal setting and task performance. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1991,16. [CrossRef]

- Meece, J.. The classroom context and students’ motivation goals. In Advances in motivation and achievement. Maehr, M.L.; Pintrich P.R.(Eds.), Publisher: Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. 1991, 7, 261–285.

- Gaa, J. The effects of individual goal-setting conferences on the academic achievement and modification of locus of control orientation. Psychol. Sch. 1979, 16(4), 591–597. [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Berg, JM.; Dutton J.E. Turn the Job You Have into the Job You Want. Harv. Bus. Rev., 2010,6 114–117.

- Schunk, D.H.). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educ Psychol., 1991, 26, 207-231. [CrossRef]

- Armand-Delille, J., Baron, A. The IABC Handbook of Organizational Communication. A Guide to Internal Communication, Public Relations, Marketing, and Leadership. Gillis T.L. ed. Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Jossey-Bass publications, San Fran-cisco, CA, 2006. www.josseybass.com.

- Peppercorn S. The Decision-Making Skills You Need for Career Success. Accessed on 16 December 2023 from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/decision-making-skills-you-need-career-success-susan-peppercorn/.

- Gati, I.; Kulcsár, V. Making better career decisions: From challenges to opportunities. J Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103545. 50th Anniversary Issue SN 0001-8791. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Brewer-Deluce, D.; Saini, J. et al. A longitudinal Q-study to assess changes in students’ perceptions at the time of pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2023 ,13, 8770 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Baldi, C.; Phillips, C.; Waikar, A. The hard truth about soft skills: what recruiters look for in business graduates. Coll. Stud. J. 2017, 50, 422–428.

- Kulcsár, V.; Dobrean, A.; Gati, I. Challenges and difficulties in career decision making: their causes, and their effects on the process and the decision. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 116:103346. [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd Ed. Sage Publications, 2002.

- Sampson, J.P.; Reardon, R.C.; Peterson, G.W.; Lenz, J.G. Career counseling and services: a cognitive information processing approach. Publisher: Thomson/Brooks/Cole, 2004.

- Yanjun, G.; Hong, D.; Lanyue, F.; Xinyi, Z. Theorizing person-environment fit in a changing career world: Interdisciplinary integration and future directions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, Article 103557. [CrossRef]

| Issue | Innovative approach |

| 1. Identifying personal strengths and weaknesses. | Utilize SWOT analysis for a comprehensive assessment, highlighting attributes like work ethic, manual dexterity, communication skills, and academic background. Leverage strengths and actively work on weaknesses for personal and professional development. |

| 2. Opportunities for growth and development. | Employ SWOT analysis as an educational tool to recognize opportunities in dental education, such as research projects, community outreach, specialized training, and professional networking. Capitalize on identified opportunities to enhance skills and knowledge. |

| 3. Recognizing threats and challenges. | Use SWOT analysis to acknowledge challenges like academic workloads, competition, evolving technology, and staying updated with practices. Develop strategies to handle challenges effectively and mitigate potential risks. |

| 4. Career planning and decision-making. | Apply SWOT analysis for informed career decisions by aligning strengths with suitable career paths. Address weaknesses through further education, training, or mentorship. |

| 5. Personal development and improvement strategies. | Develop action plans post-SWOT analysis. For example, if communication skills are identified as a weakness, engage in public speaking groups or communication workshops. Capitalize on strengths through extracurricular activities and mentorship. |

Strengths

|

Weaknesses

|

Opportunities

|

Threats

|

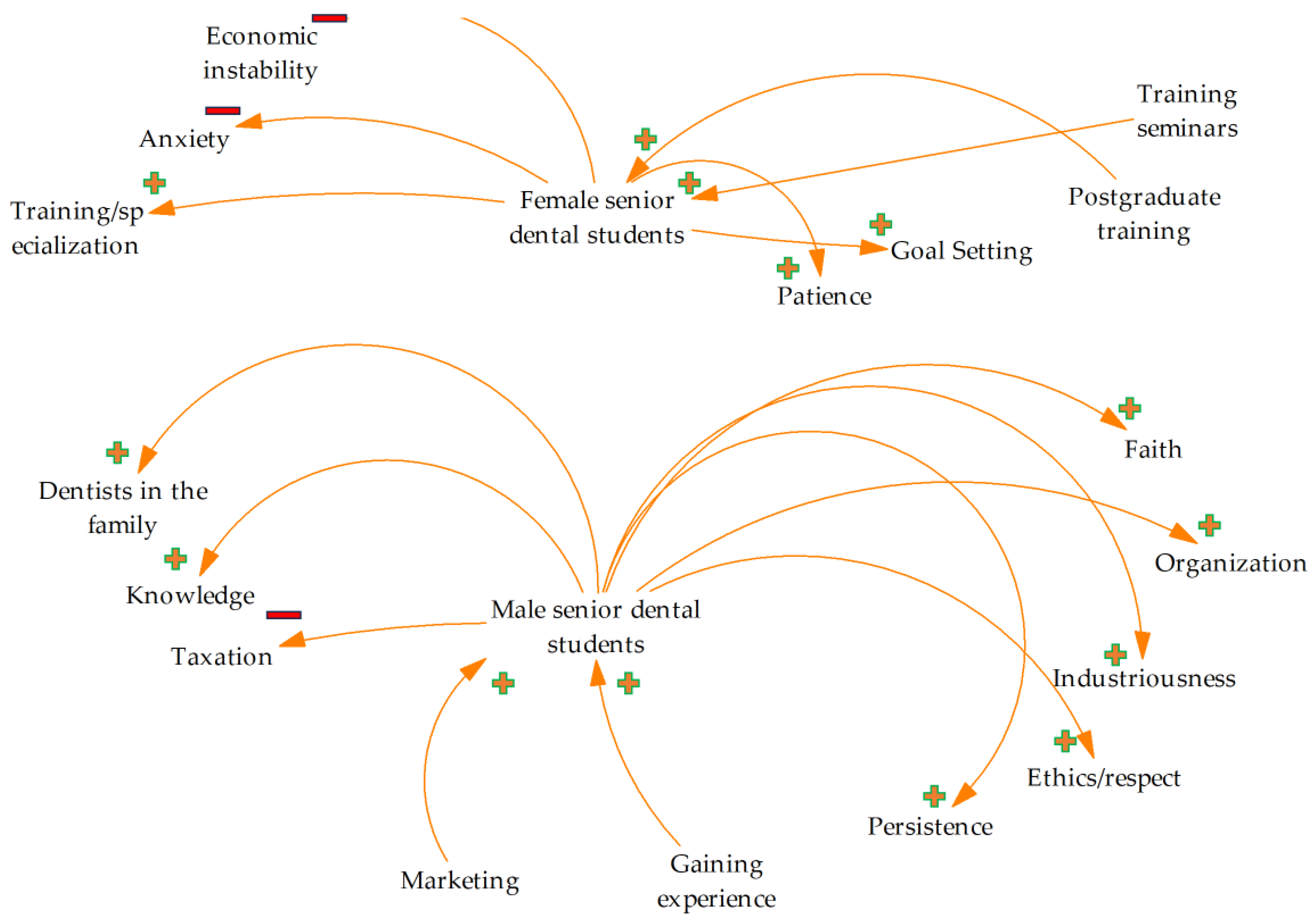

| Total (N=114) | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=43) | Female (n=71) | |||||

| n | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Strengths | ||||||

| Industriousness | 28 | 24.6% | 10a | 23.3% | 18a | 25.4% |

| Organization skills | 56 | 49.1% | 14a | 32.6% | 42b | 59.2% |

| Knowledge | 30 | 26.3% | 17a | 39.5% | 13b | 18.3% |

| Communication skills | 57 | 50.0% | 22a | 51.2% | 35a | 49.3% |

| Practical skills | 20 | 17.5% | 10a | 23.3% | 10a | 14.1% |

| Personal traits1 | 38 | 33.3% | 12a | 27.9% | 26a | 36.6% |

| Weaknesses | ||||||

| Anxiety | 47 | 41.2% | 12a | 27.9% | 35b | 49.3% |

| Personal traits2 | 35 | 30.7% | 14a | 32.6% | 21a | 29.6% |

| Lack of initial capital | 28 | 24.6% | 10a | 23.3% | 18a | 25.4% |

| Organization difficulties | 19 | 16.7% | 9a | 20.9% | 10a | 14.1% |

| Lack of experience or clinical skills | 16 | 14.0% | 9a | 20.9% | 7a | 9.9% |

| Perfectionism | 12 | 10.5% | 7a | 16.3% | 5a | 7.0% |

| Opportunities | ||||||

| Collaboration with experienced dentists in dental practice | 38 | 33.3% | 18a | 41.9% | 20a | 28.2% |

| Training/Specialization | 31 | 27.2% | 6a | 14.0% | 25b | 35.2% |

| Dentists/Physicians in the family | 13 | 11.4% | 9a | 20.9% | 4b | 5.6% |

| Work as an intern | 12 | 10.5% | 3a | 7.0% | 9a | 12.7% |

| Threats | ||||||

| Economic instability | 88 | 77.2% | 27a | 62.8% | 61b | 85.9% |

| Saturated profession | 30 | 26.3% | 15a | 34.9% | 15a | 21.1% |

| High initial capital | 27 | 23.7% | 8a | 18.6% | 19a | 26.8% |

| Taxation | 16 | 14.0% | 11a | 25.6% | 5b | 7.0% |

| Political instability | 15 | 13.2% | 3a | 7.0% | 12a | 16.9% |

|

1 persistence, patience, attention to detail, consistency, decisiveness, critical thinking 2 short-tempered, impatient, over-patient, indecisive Note: Values in the same row not sharing the same subscript are significantly different at p < .05. Cells with no subscript are not included in the test. a, b: significant differences | ||||||

| Total | Sex | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||||

| n | % | N | % | n | % | |

| Values | ||||||

| Industriousness | 28 | 24.6% | 11a | 25.6% | 17a | 23.9% |

| Persistence | 40 | 35.1% | 17a | 39.5% | 23a | 32.4% |

| Patience | 25 | 21.9% | 9a | 20.9% | 16a | 22.5% |

| Ethics/Respect | 33 | 28.9% | 13a | 30.2% | 20a | 28.2% |

| Faith | 15 | 13.2% | 6a | 14.0% | 9a | 12.7% |

| Organization | 25 | 21.9% | 10a | 23.3% | 15a | 21.1% |

| Goal setting | 13 | 11.4% | 4a | 9.3% | 9a | 12.7% |

| Actions | ||||||

| Training/Seminars | 66 | 57.9% | 20a | 46.5% | 46a | 64.8% |

| Gaining experience | 34 | 29.8% | 14a | 32.6% | 20a | 28.2% |

| Participate in Scientific Conferences | 19 | 16.7% | 3a | 7.0% | 16b | 22.5% |

| Postgraduate studies | 17 | 14.9% | 5a | 11.6% | 12a | 16.9% |

| Marketing | 13 | 11.4% | 6a | 14.0% | 7a | 9.9% |

| Action clusters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Taking advantage of all available options (n=49) |

2 Focus on professional experience (n=65) |

|||

| Predictors | N | % | n | % |

| Training/Seminars | 27 | 55.1% | 39 | 60.0% |

| Gaining experience | 10 | 20.4% | 24 | 36.9% |

| Participate in Scientific Conferences | 19 | 38.8% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Postgraduate studies | 17 | 34.7% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Marketing | 13 | 26.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| B | S.E. | Wald | Df | p | OR | 95% C.I. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Industriousness | -1.085 | .503 | 4.652 | 1 | .031 | .338 | .126 | .906 | |

| Personal traits (strengths) | 1.072 | .433 | 6.130 | 1 | .013 | 2.922 | 1.250 | 6.828 | |

| Economic instability | .767 | .515 | 2.216 | 1 | .137 | 2.152 | .784 | 5.905 | |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | .008 | .430 | .000 | 1 | .986 | 1.008 | .433 | 2.342 | |

| Constant | -1.012 | .752 | 1.812 | 1 | .178 | .364 | |||

| Mindset category | Profile | Actions taken by the person | Educational approaches from dental schools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed mindset | "Well, that’s it. I’m stuck” | Mistakes equate to failure | Lack of receptivity to feedback, aversion to risk, and stagnant self-perception |

| Growth mindset | “Interesting. What can I learn from this?” | Mistakes seen as opportunities for growth | Openness to feedback, actively seeks learning opportunities, values self-growth |

| Evolutionary mindset | “What does this say about me: how can I grow myself?” | Mistakes seen as a pathway to self-knowledge | Introspection, continuous self-learning, and a deep commitment to personal growth |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).