Submitted:

21 December 2023

Posted:

22 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

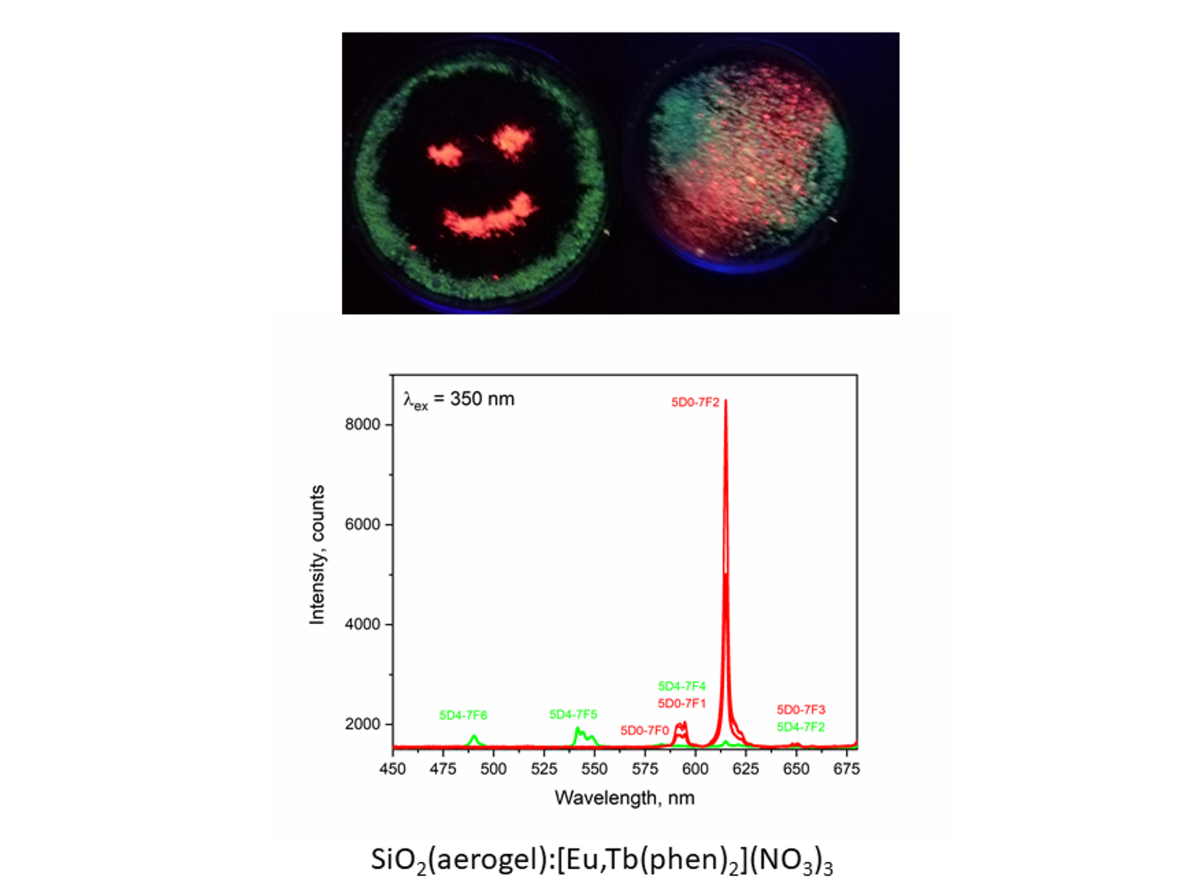

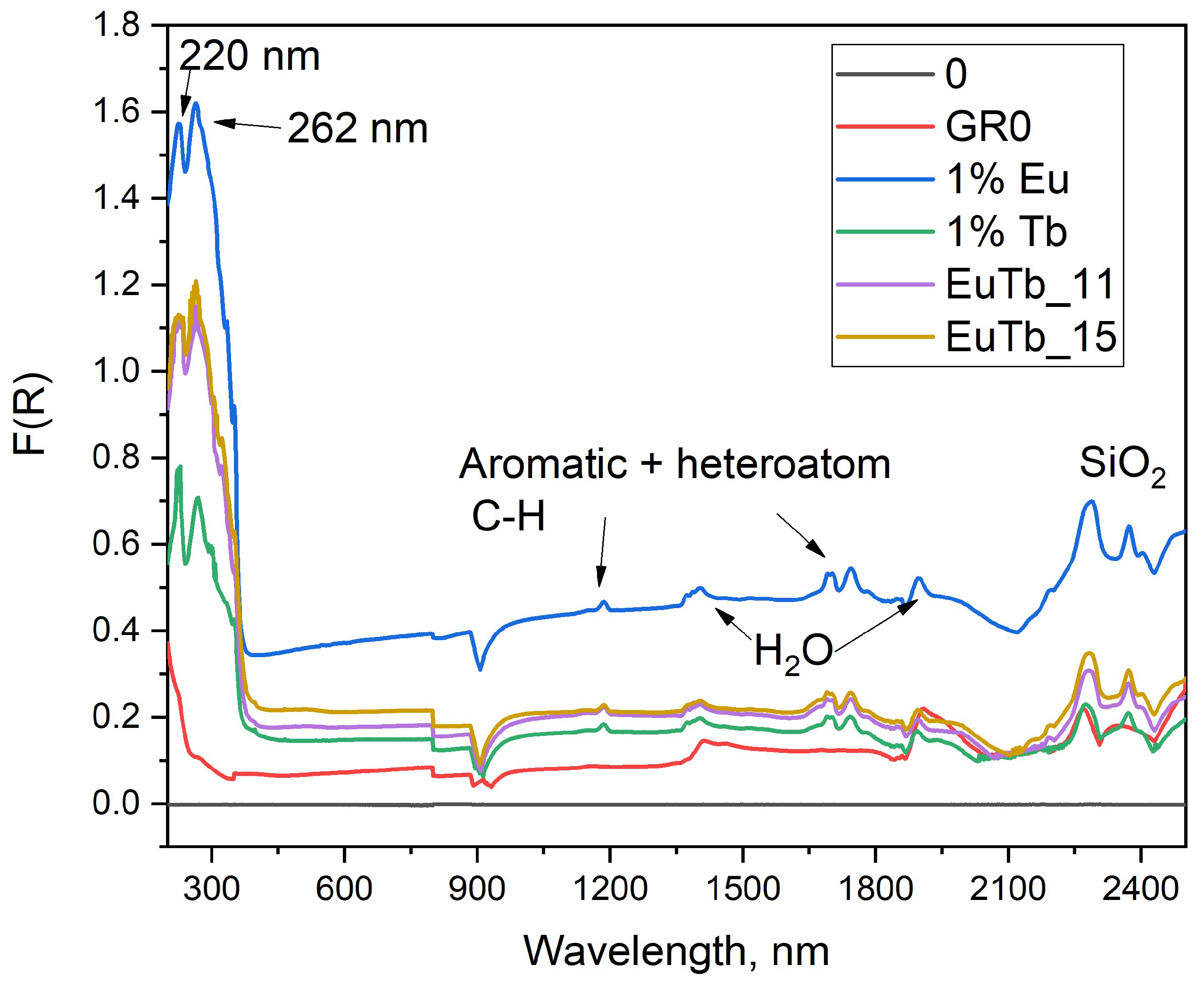

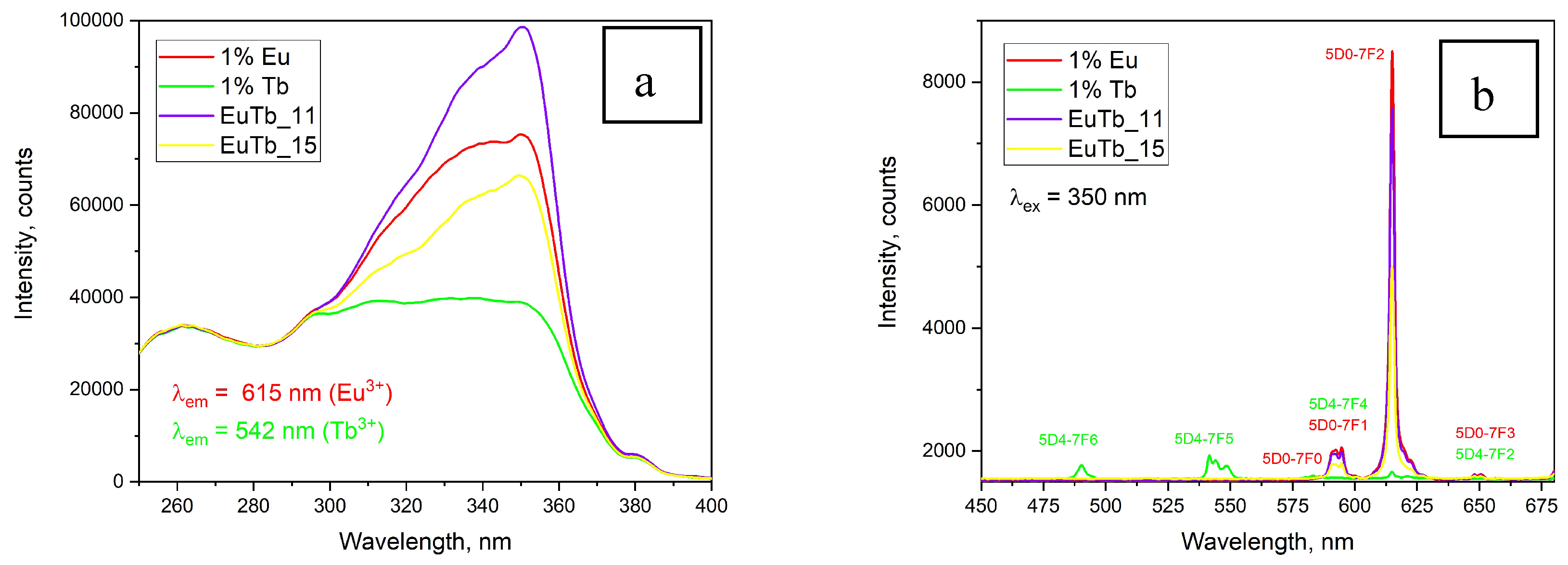

2.1. Optical properties

2.2. Thermal properties

| Sample | α | λ | Δλ | e | Δe | ρ | nLn/nSiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/m.K | W/m.K | W.s1/2/m.K | W.s1/2/m.K | g/cm3 | |||

| GR0 | 0 | 0.0640 | 0.0002 | 145.3896 | 0.8531 | 0.45 | 0 |

| 1% Eu | 1.1 | 0.0523 | 0.0001 | 95.6041 | 0.5516 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| 1% Tb | 1.1 | 0.0467 | 0.0001 | 71.2591 | 0.5505 | 0.18 | 0.01 |

| EuTb_11 | 1.1 | 0.0510 | 0.0001 | 90.2086 | 0.4896 | 0.18 | 0.01 |

| EuTb_15 | 1.1 | 0.0523 | 0.0003 | 95.5750 | 1.1232 | 0.18 | 0.01 |

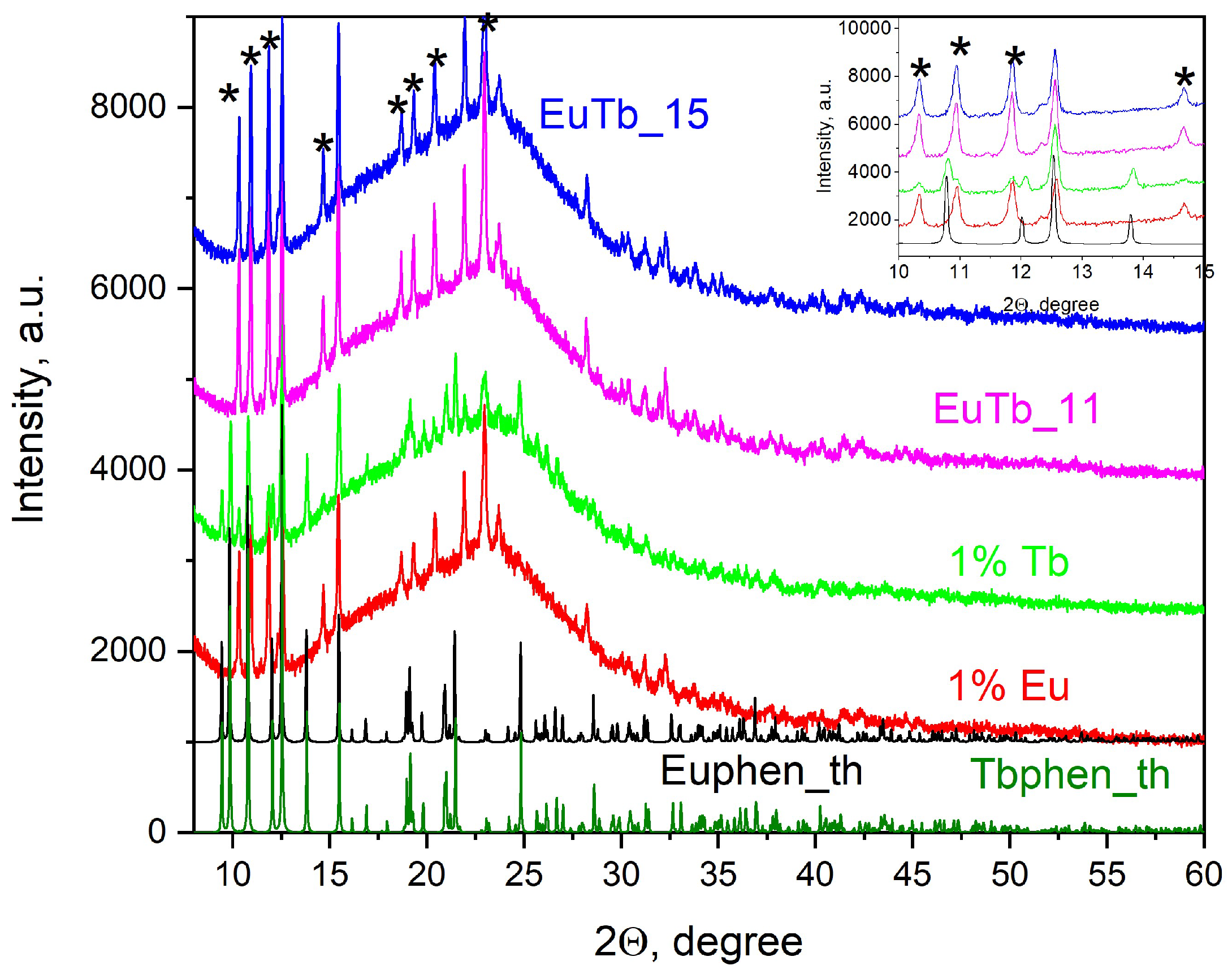

2.3. X-ray diffraction results

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- M. A. Aegerter, N. Leventis, and M. M. Koebel, Aerogels Handbook. New York: Springer, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Gutzov, N. Danchova, R. Kirilova, V. Petrov, and S. Yordanova, “Preparation and luminescence of silica aerogel composites containing an europium (III) phenanthroline nitrate complex,” J. Lumin., vol. 193, pp. 108–112, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Gutzov, D. Shandurkov, N. Danchova, V. Petrov, and T. Spassov, “Hybrid composites based on aerogels: preparation, structure and tunable luminescence,” J. Lumin., vol. 251, p. 119171, 2022.

- D. Shandurkov, P. Ignatov, I. Spassova, and S. Gutzov, “Spectral and texture properties of hydrophobic aerogel powders obtained from room temperature drying,” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 1–12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Hull, J. R. M. Osgood, J. Paris!, and H. Warlimont, Spectroscopic properties of Rare Earths in Optical Materials. Springer, 2014.

- Koseva, P. Tzvetkova, P. Ivanov, A. Yordanova, and V. Nikolova, “Terbium and europium co-doped NaAlSiO4 nano glass-ceramics for LED application,” Optik (Stuttg)., vol. 137, pp. 45–50, 2017.

- Koseva, P. Tzvetkov, P. Ivanov, A. Yordanova, and V. Nikolov, “Some investigations on Tb3+ and Eu3+ doped Na2SiO3 as a material for LED application,” Optik (Stuttg)., vol. 168, pp. 376–383, 2018.

- S. V. Kameneva et al., “Epoxide synthesis of binary rare earth oxide aerogels with high molar ratios (1:1) of Eu, Gd, and Yb,” J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, High-Entropy Materials A Brief Introduction. Springer Singapore, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Workman and L. Weyer, Practical Guide to Interpretive Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, 2008.

- T. Zahariev et al., “Phenanthroline chromophore as efficient antenna for Tb3+ green luminescence: A theoretical study,” Dye. Pigment., vol. 185, p. 108890, 2020.

- K. Binnemans, “Interpretation of europium(III) spectra,” Coord. Chem. Rev., vol. 295, pp. 1–45, 2015.

- G. Blasse and B. C. Grabmaier, Luminescent Materials. Telos: Springer-Verlag, 1994.

- Fumito FUJISHIRO, M. MURAKAMI, T. HASHIMOTO, and M. TAKAHASHI, “Orange luminescence of Eu3+ doped CuLaO2 delafossite oxide,” J. Ceram. Soc. Japan, vol. 118, no. 12, pp. 1217–1220, 2010.

- P. Gomez-Romero and C. Sanchez, Functional Hybrid Materials. Wiley-VCH, 2003. [CrossRef]

- G. H. Dieke, H. M. Crosswhite, and H. Crosswhite, Spectra and energy levels of rare earth ions in crystals. Interscience Publishers, 1968.

- S. Singh and D. Singh, “Synthesis and spectroscopic investigations of trivalent europium-doped M2SiO5 (M = Y and Gd) nanophosphor for display applications,” J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron., vol. 31, pp. 5165–5175, 2020.

- Z. Boruc, B. Fetlinski, M. Kaczkan, S. Turczynski, D. A. Pawlak, and M. Malinowski, “Temperature and Concentration Quenching of Tb3+ Emissions in Y4Al2O9 Crystals,” J. Alloys Compd., vol. 532, pp. 92–97, 2012.

- S. Culubrk, V. Lojpur, Z. Antic, and M. D. Drami, “Structural and optical properties of europium doped Y2O3 nanoparticles prepared by self-propagation room temperature reaction method,” J. Res. Phys., vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 39–45, 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. Xie, Y.-L. He, and Z.-J. Hu, “Theoretical study on thermal conductivities of silica aerogel composite insulating material,” Int J Heat Mass Transf, vol. 58, pp. 540–552, 2013.

- P. Lindenberg et al., “New insights into the crystallization of polymorphic materials:from real-time serial crystallography to luminescence analysis,” React. Chem. Eng., vol. 4, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Mirochnik, B. V. Bukvetskii, P. A. Zhikhareva, and V. E. Karasev, “Crystal Structure and Luminescence of the [Eu(Phen)2(NO3)3] Complex. The Role of the Ion-Coactivator,” Russ. J. Coord. Chem., vol. 27, pp. 443–448, 2001.

- D.-Y. Wei, J.-L. Lin, and Y.-Q. Zheng, “Note: The crystal structure of Tris(nitrato-O,O’)bis(1,10-phenanthroline-N,N’)terbium(III),” J. Coord. Chem., vol. 55, no. 11, pp. 1259–1262, 2002. [CrossRef]

- R. Yadav et al., “Preparation of Holmium Oxide Solution as a Wavelength Calibration Standard for UV–Visible Spectrophotometer,” Mapan - J. Metrol. Soc. India, vol. 37, no. 3, 2021.

- K. Suzuki et al., “Reevaluation of absolute luminescence quantum yields of standard solutions using a spectrometer with an integrating sphere and a back-thinned CCD detector,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., vol. 11, no. 42, pp. 9850–9860, 2009. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Chemistry | QY, red % |

QY, green % |

IED/IMD | x | y | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR0 | SiO2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1%Tb | SiO2:0.01Tb | - | 6.3 | 0.39 | 0.631 | 0.340 | 0.03 |

| 1%Eu | SiO2:0.01Eu | 35 | - | 5.98 | 0.358 | 0.486 | 0.156 |

| EuTb1_1 | SiO2:0.005Eu;0.005Tb | 30 | - | 5.92 | 0.626 | 0.336 | 0.038 |

| EuTb1_5 | SiO2:0.0017Eu;0.0083Tb | 32 | - | 6.06 | 0.597 | 0.322 | 0.081 |

| Euphen | [Eu(phen)2](NO3)3 | 35 | - | 7.25 | 0.309 | 0.602 | 0.089 |

| Tbphen | [Tb(phen)2](NO3)3 | - | 13 | 0.37 | 0.665 | 0.333 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).