Submitted:

21 December 2023

Posted:

22 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study areas and bird data

2.2. Assessing human perception on urban birds

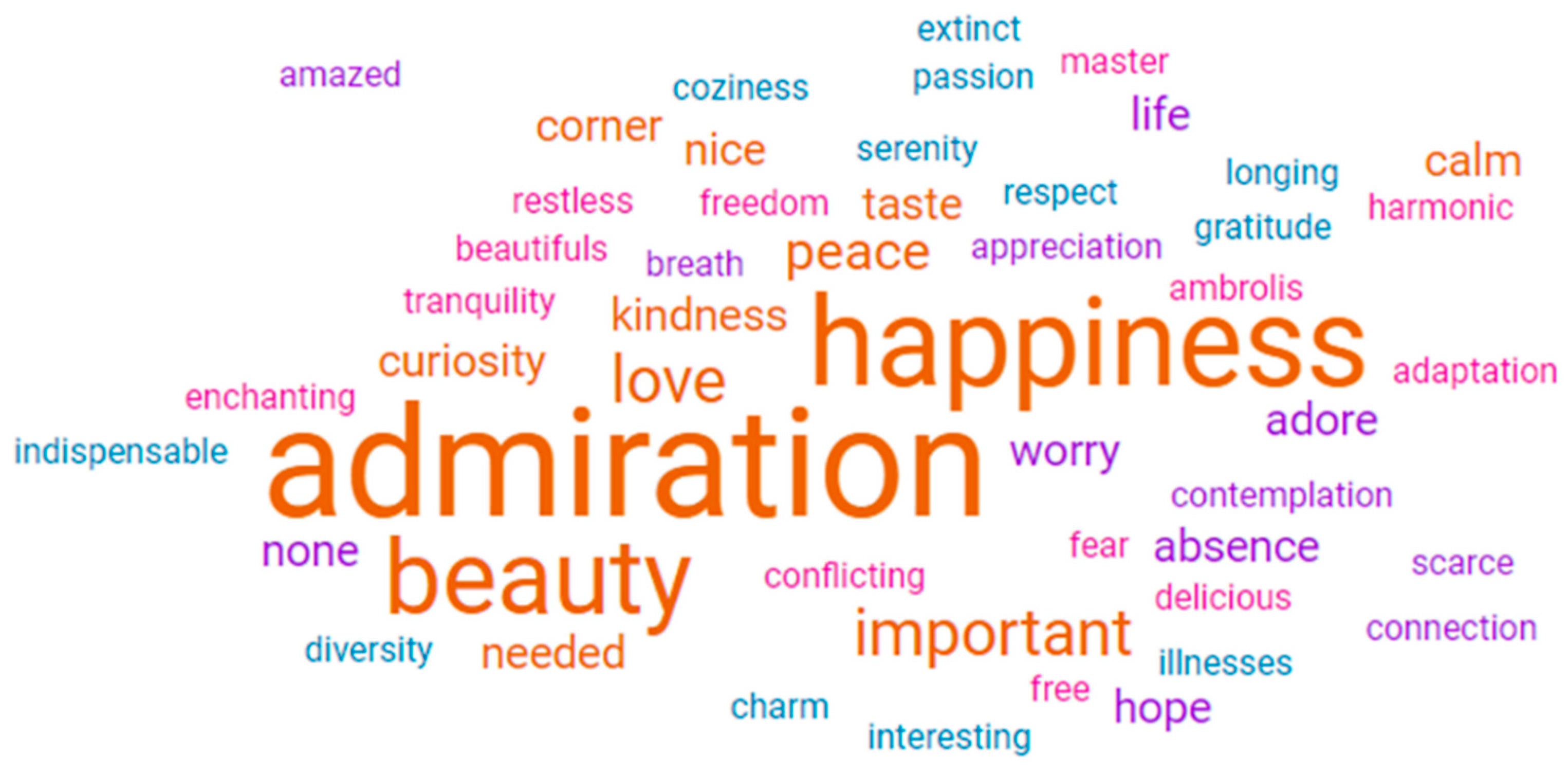

- Describe in one word how you feel about urban birds

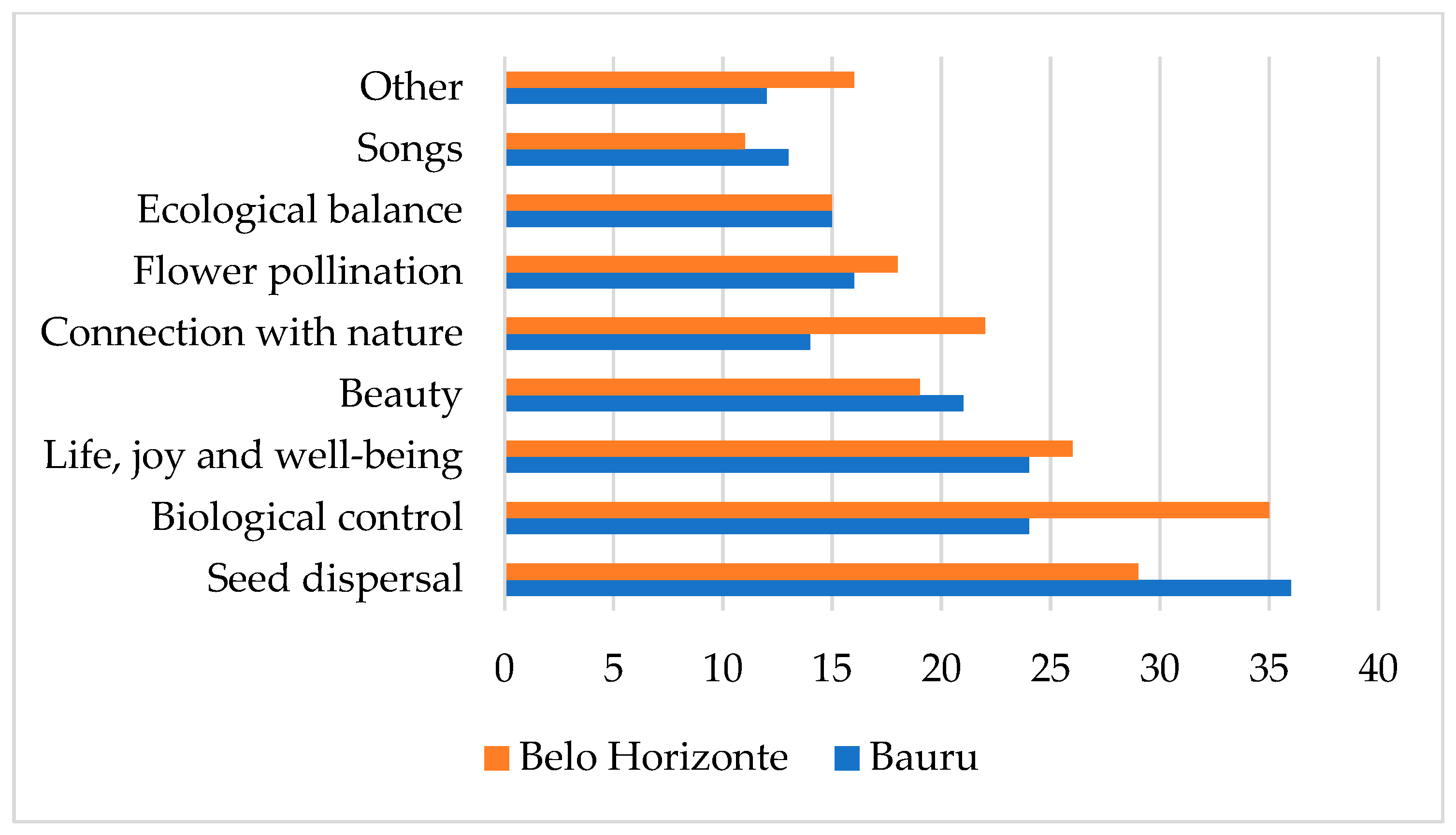

- What do you believe is a benefit of birds in cities?

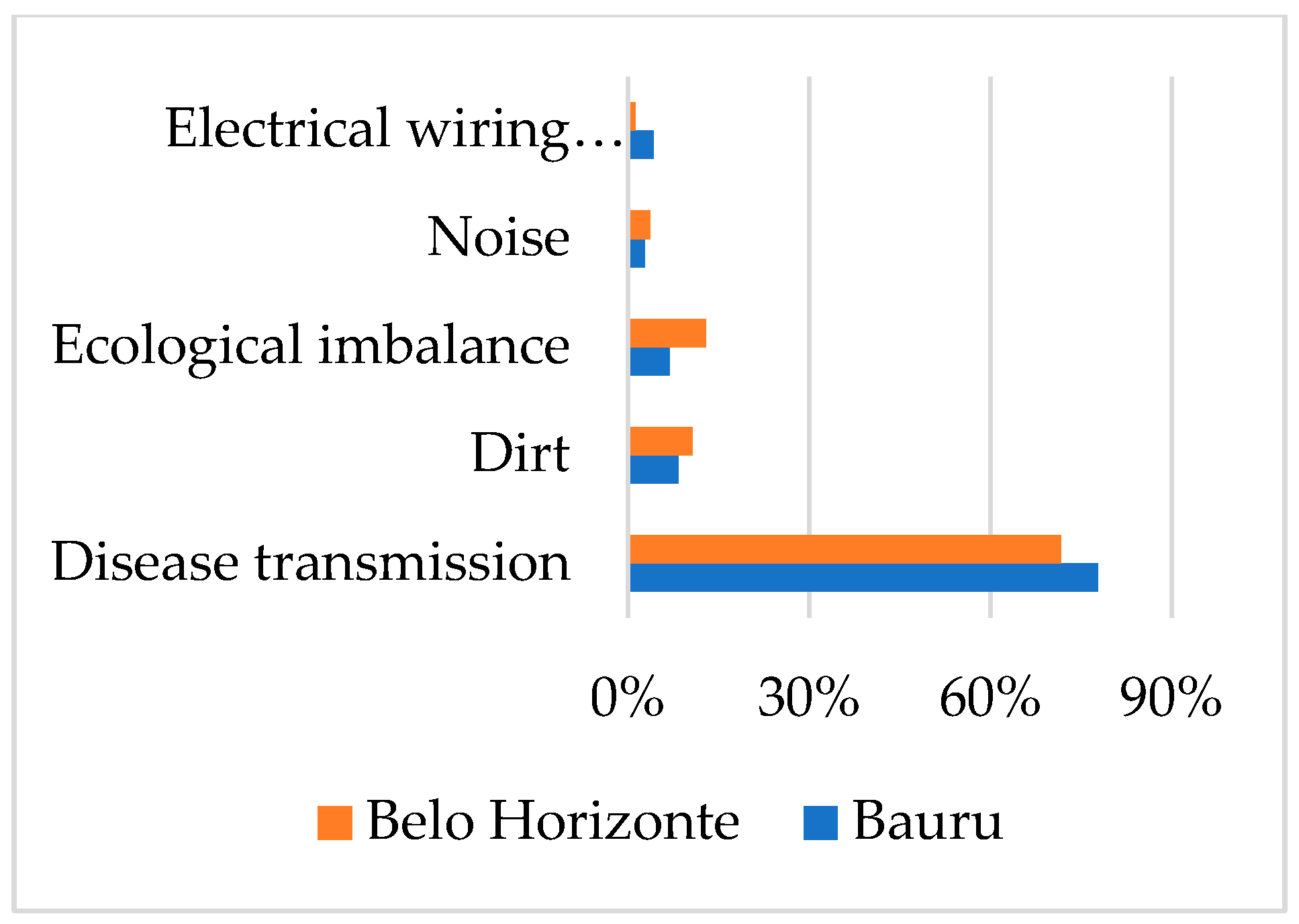

- Do you believe that there is a harm caused by birds in cities?

- 4.

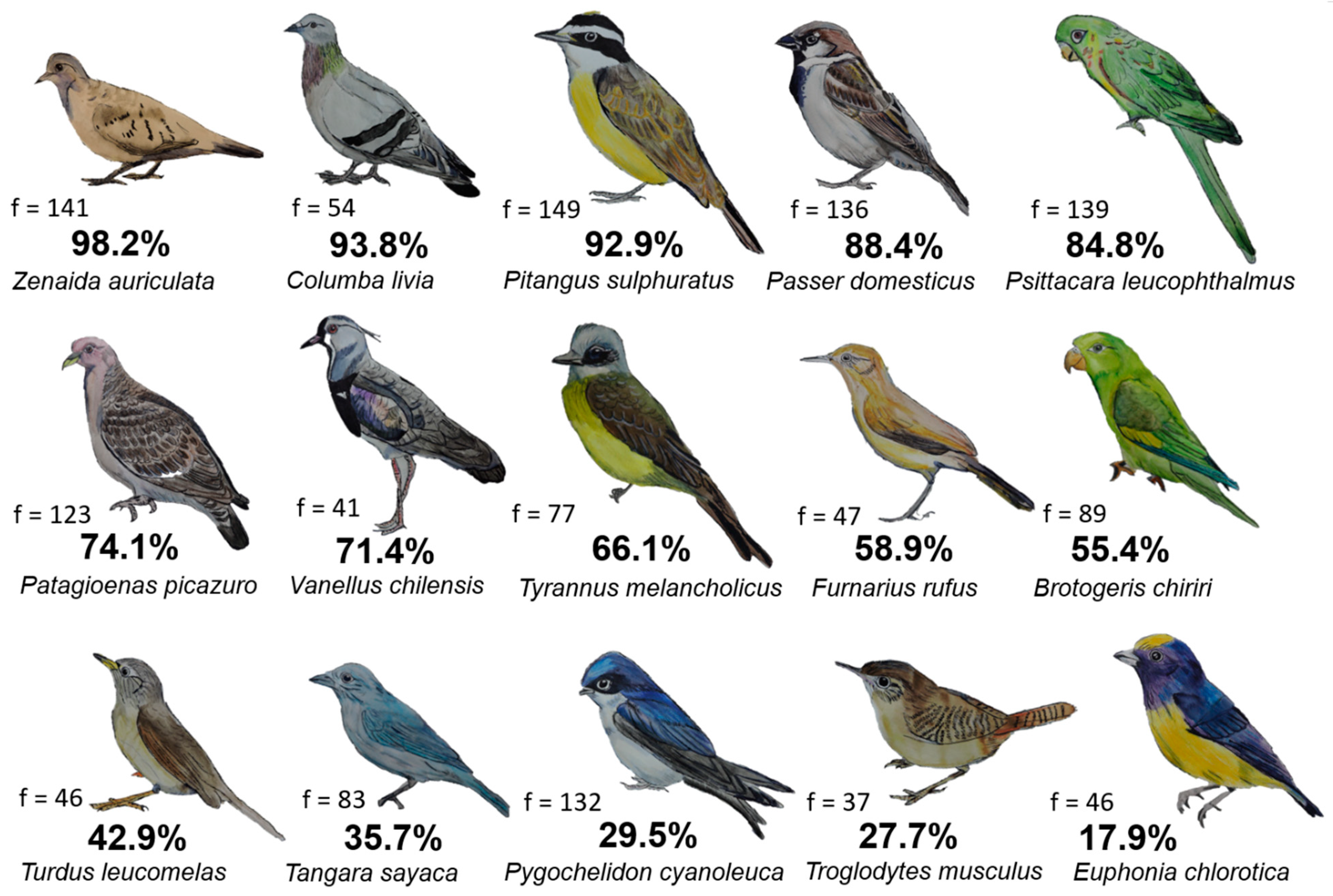

- How many different birds do you think you have seen within the urban area of Bauru?

- 5.

- 371 bird species have already been recorded within the entire territory of Belo Horizonte (which includes forested, rural and urban areas)/ 276 bird species have already been recorded within the entire territory of Bauru (which includes forested, rural and urban areas). How many do you believe are capable of living in the urban area?

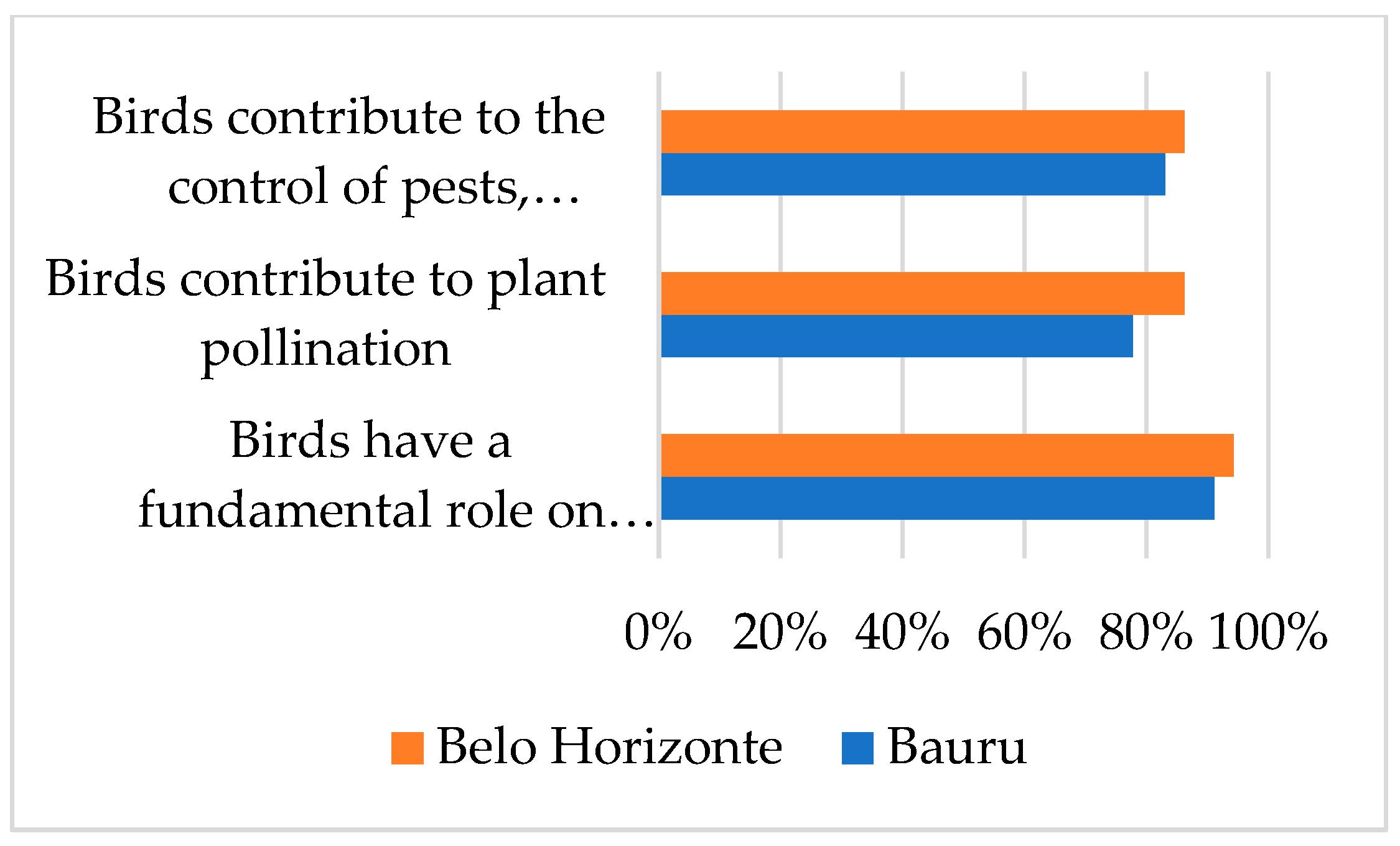

- Birds contribute to seed dispersal

- Birds contribute to plant pollination

- Birds contribute to the control of pests, insects and other animals.

- Birds contribute to the prevention of the incidence of diseases

2.3. Analyzing peoples’ perceptions towards birds

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soulsbury, C.D., White, P.C.L. Human–wildlife interactions in urban areas: a review of conflicts, benefits and opportunities. Wildl. Res. 2015. 42, 541. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.K., Magle, S.B., Gallo, T. Global trends in urban wildlife ecology and conservation. Biol. Conserv. 261, 2021. 109236. [CrossRef]

- Maddox, D.; Nagendra, H.; Elmqvist, T.; Russ A. Chapter 1: Advancing Urbanization. In: Cornell University. Urban Environmental Education. 2017. Cornell University.

- Schwarz, N.; Moretti, M.; Bugalho, M.N.; Davies, Z.G.; Haase, D.; Hack, J.; Hof, A.; Melero, Y.; Pettf, T.J. & Knappk, S. Understanding biodiversity-ecosystem service relationships in urban areas: A comprehensive literature review. Ecosystem Services, 2017. 27: 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Vailshery, L.S.; Jaganmohan, M. & Nagendra, H. Effect of street trees on microclimate and air pollution in a tropical city. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 2013. 12(3), 408–415. [CrossRef]

- Derr, V.; Chawla, L.; Pevec, I. Chapter 16: Early Childhood. In: Cornell University. Urban Environmental Education. 2017, Cornell University.

- Sandifer, P. A., Sutton-Grier, A. E., Ward, B. P. Exploring connections among nature, biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human health and well-being: Opportunities to enhance health and biodiversity conservation. Ecosystem Services, 2015, 12, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., De Vries, S., Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annual Review of Public Health, 2014. 35(1), 207–228. [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Hardcover, United States, April, 2005.

- Sweet, F.S.T.; Noack, P.; Hauck, T.E.; Weisser, W.W. The relationship between knowing and liking for 91 urban animal species among students. Animals, 2023, 13(3), 488. [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.M.; Rostovskaya, E.; Birks, J. & Wierzbowska, I.A. Perceptions and attitudes to understand human-wildlife conflict in an urban landscape – A systematic review. Ecological Indicators, 2023 151. [CrossRef]

- Elliot, E.E., Vallance, S., Molles, L.E. Coexisting with coyotes (Canis latrans) in an urban environment. Urban Ecosyst, 2016, 19, 1335–1350. [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, T., & Østdahl, T. Animal-related attitudes and activities in an urban population. Anthrozoos, 17(2), 2004, 109– 129. [CrossRef]

- Hosaka, T., Sugimoto, K., & Numata, S. Childhood experience of nature influences the willingness to coexist with biodiversity in cities. Palgrave Communications, 2017, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y. Space and Place: the perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1996.

- Bennett, N.J., Using perceptions as evidence to improve conservation and environmental management. Conserv Biol 2016, 30, 582–592. [CrossRef]

- Dickman, A.J. Complexities of conflict: the importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human–wildlife conflict. Anim. Conserv. 2010, 13, 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Pejchar, L.; Pringlea, R.M.; Ranganathana, J.; Zookb, J.R.; Duranc, G.; Oviedoc, F.; Daily, G.C. Birds as agents of seed dispersal in a human-dominated landscape in southern Costa Rica. Biological Conservation, 2008, 141: p. 536-544. [CrossRef]

- Sick, H. Ornitologia Brasileira. Nova Fronteira., Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 1997.

- Wenny, D.G.; Sekercioglu, Ç.H.; Cordeiro, N.J.; Rogers, H.S. & Kelly, D. Chapter five: Seed Dispersal by Fruit-Eating Birds. In: Sekercioglu, Ç.H.; Wenny, D.G. & Whelan, C.J. Why Birds Matter - Avian Ecological Function and Ecosystem Services. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Whelan, C.J.; Sekercioglu, Ç.H.; Wenny, D.G. Why birds matter: from economic ornithology to ecosystem services. Journal of Ornithology, July 2015. 20 July. [CrossRef]

- Unterweger, P., Schrode, N., & Betz, O. Urban Nature: Perception and Acceptance of Alternative Green Space Management and the Change of Awareness after Provision of Environmental Information. A Chance for Biodiversity Protection. Urban Science, 2017, 1(3), 24. [CrossRef]

- Pena, J. C., Martello, F., Ribeiro, M. C., Armitage, R. A., Young, R. J., & Rodrigues, M. Street trees reduce the negative effects of urbanization on birds. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12(3), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiro. 2022. ftp://ftp.ibge.go.

- SEMMA. Plano Municipal de Conservação e Recuperação da Mata Atlântica e do Cerrado., 2015. SEMMA - Secretaria Municipal do Meio Ambiente, Prefeitura de Bauru.

- Pena, J.C.C.; Magalhães, D.M.; Moura, A.C.M.; Young, R.J. & Rodrigues, M. The Green Infrastructure of a Highly Urbanized Neotropical City: the Role of the Urban Vegetation in Preserving Native Biodiversity. Revista Da Sociedade Brasileira de Arborização Urbana, 2016, 11(4), 66. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, H.; Cahill, A.; Jones, M.; Marsden, S. Estimating Bird Densities Using Distance Sampling. In: Lloyd, M.; Jones; S. Marsden. (Eds). Bird surveys - Expedition Field Techniques, 2000, pp. 34-55.

- Gregory, R. D., Gibbons, D. W., & Donald, P. F. Bird Census And Survey Techniques. In W. J. Sutherland, I. Newton, & R. Green (Eds.), Bird Ecology and Conservation: A Handbook of Techniques, 2004, pp. 17–56. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Pena, J.C.; Ovaskainen, O.; Macgregor-Fors, I.; Teixeira, C.P.; Ribeiro, M.C. The relationships between urbanization and bird functional traits across The streetscape. Landscape and Urban Planning, 2023, vol. 232. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.R.G. Para entender a pesquisa qualitativa. Bauru: Unesp-FAAC, 2017.

- Farinha, B.S. Árvores para quem? Um estudo sobre percepção ambiental e distribuição socioeconômica da floresta urbana na cidade de São Paulo. Dissertação de Mestrado em Conservação em Ecossistemas Florestais, Escola Superior de Agricultura "Luiz de Queiroz" (ESALQ), Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Piracicaba, SP, 70p. 2022. https://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/11/11150/tde-06042022-141809/publico/Barbara_Saeta_Farinha_versao_revisada.pdf.

- Mota, M.D.S.; Régis, M.D.M. & Nascimento, A.P.B. (2019). Perfil e e percepção ambiental dos frequentadores do Parque Tenente Siqueira Campos (Trianon), no Município de São Paulo/SP. Periódico Eletrônico Fórum Ambiental da Alta Paulista, 2019. v.15. n. 2, p. 95-110.

- Régis, M.D.M.; Lamano-Ferreira, A.P.N.; Ramos, H.R. Relato Técnico: percepção de frequentadores sobre espaço, estrutura e gestão do Parque da Água Branca, SP. Periódico Técnico e Científico Cidades Verdes, v. 3, n. 6, p. 43-54, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Frankenthal, R. Entenda a escala Likert e como aplicá-la em sua pesquisa, 2017. https://mindminers.com/blog/entenda-o-que-e-escala-likert/.

- Borysiak, J.; Stepniewska, M. Perception of the Vegetation Cover PatternPromoting Biodiversity in Urban Parks by Future Greenery Managers. Land, 2022, 11, 341. [CrossRef]

- Harris, E., De Crom, E., Wilson, A., Pigeons and people: mortal enemies or lifelong companions? A case study on staff perceptions of the pigeons on the University of South Africa, Muckleneuk campus. J. Public Aff. 2016, 16, 331–340. [CrossRef]

- Lovasi, G.S.; Quinn, J.W.; Neckerman, K.M.; Perzanowski, M.S. & Rundle, A. Children living in areas with more street trees have lower prevalence of asthma, Short Report, United States, 2008.

- Adams, J.D; Greenwood, D.A.; Thomashow, M.; Russ, A. (2017) Chapter 7: Sense of place. In: Cornell University. Urban Environmental Education. Cornell University, 2017.

- Graviola, G.R.; Ribeiro, M.C.; Pena, J.C. Reconciling humans and birds when designing ecological corridors and parks within urban landscapes. Ambio, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bhakti, T.; Lodi, M.L.; Marujo, L.S.; Pena, J.C. & Rodrigues, M. Beyond birds’ conservation: Engaging communities for the conservation of urban green spaces. El Hornero 38 (1), 2023 ·. [CrossRef]

- Pett, T. J., Shwartz, A., Irvine, K. N., Dallimer, M.,; Davies, Z. G. Unpacking the people-biodiversity paradox: A conceptual framework. Bio Scienc, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Konig, H.J., Kiffner, C., Kramer-Schadt, S., Fürst, C., Keuling, O., Ford, A.T., Human–wildlife coexistence in a changing world. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 786–794. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. A imagem da cidade. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1960.

- Rosa, G. Por uma ressignificação do Rio Tietê no Oeste Paulista: Barra Bonita e Pederneiras. Dissertação de Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação (FAAC), UNESP (Universidade Estadual Paulista "Júlio de Mesquita Filho"), Bauru, SP, 212p. 2020.

- Foloni, F.M. Rios sobre o asfalto: conhecendo a paisagem para entender as enchentes, 210p. Dissertação de Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade Estadual Paulista. Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação, Bauru, 2018.

- Hurlbert, S. Pseudoreplication and the Design of Ecological Field Experiments. Ecological Monographs, Vol. 54, No. 2., pp. 187-211, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Marzluff, J.M.; Shulenberger, E.; Endlicher, W.; Simon, U.; Brunnen C. Z.; Alberti, M.; Bradley, G.; Ryan, C. An introduction to Urban Ecology as an interaction between humans and nature. In:___. (Org.) Urban Ecology: an International Perspective on the Interaction Between Humans and Nature. Springer, New York, 2008.

- Pallasmaa, J. Os Olhos da Pele: a Arquitetura e os Sentidos. Bookman, 1ed., 2011Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196.

| Variable | Cities | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bauru | Belo Horizonte | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 41 (36.6%) | 55 (44.7%) | |

| Female | 71 (63.4%) | 66 (53.7%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| Age | |||

| Until 25 years | 33 (29.5%) | 16 (13.0%) | |

| 26 to 35 years | 36 (32.1%) | 44 (35.8%) | |

| 36 to 45 years | 12 (10.7%) | 32 (26%) | |

| 46 to 60 years | 22 (19.6%) | 17 (13.8%) | |

| 61 to 74 years | 8 (7.1%) | 14 (11.4%) | |

| More than 75 years | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Education | |||

| Elementary and middle school | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| High school | 9 (8.0%) | 4 (3.3%) | |

| Bachelor study incomplete | 29 (25.9) | 12 (9.8%) | |

| Bachelor study complete | 24 (21.4%) | 36 (29.3%) | |

| Master ans doctarate degree | 47 (42.0%) | 71 (57.6%) | |

| Post-doctoral degree | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Family Income | |||

| Untill 1000 reais | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| 1001 to 3000 reais | 36 (32.1%) | 18 (14.6%) | |

| 3001 to 5000 reais | 29 (25.9%) | 20 (16.3%) | |

| 5001 to 10000 reais | 25 (22.3%) | 31 (25.2%) | |

| More than 10000 reais | 16 (14.3%) | 47 (38.2%) | |

| No anwser | 4 (3.6%) | 6 (4.9%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).