1. Introduction

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM) and phaeohyphomycosis (PHM) are fungal infections primarily instigated by dematiaceous fungi, predominantly classified under the

Herpotrichiellaceae family [

1,

2]. CBM is categorized by the World Health Organization as a neglected tropical disease, primarily due to its higher prevalence in economically disadvantaged or developing countries situated within tropical or subtropical regions [

3,

4,

5].

CBM prevails endemically in countries spanning Latin America, Central America, Africa, and Asia, with a notable predilection for rural laborers [

2,

3,

6,

7]. In contrast, PHM is reported in diverse nations globally and exhibits a similar affinity for tropical and subtropical climates, predominantly affecting immunocompromised individuals, thus denoting it as an opportunistic infection [

1,

8,

9].

Chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis are both mycoses primarily transmitted through direct contact with contaminated materials, often resulting from traumatic injuries. These materials may encompass plant thorns, branches, soil, and various other organic components [

1,

2].

The clinical manifestations of both infections are intricate, often mirroring other maladies, thereby complicating the process of differential diagnosis. Consequently, laboratory support is frequently imperative [

8,

10,

11]. In this context, the prevailing diagnostic gold standard for both infections are the identification of muriform cells in the case of chromoblastomycosis and dematiaceous hyphae in the case of phaeohyphomycosis through direct mycological examination [

1,

2,

12].

In the presumptive species-level identification, morphological analyses are conducted based on the macrocolony's appearance and the arrangement and structure of conidial and hyphal elements [

2,

13,

14]. However, due to the phenotypic similarities between the species responsible for CBM and PHM, such analyses become notably subjective [

8,

14].

Owing to this subjectivity, genetic sequencing of the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region has emerged as the most widely employed molecular technique for identifying agents of chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, this methodology is associated with high costs and is relatively inaccessible in regions where these infections are more endemic. Consequently, there is a pressing need for new, cost-effective molecular approaches suitable for resource-limited laboratories, enabling rapid and specific species identification [

15].

In light of these considerations, the present study aimed to develop a molecular approach based on restriction fragment length polymorphism of the ITS region for the identification of species among the primary causative agents of chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis in the Northern region of Brazil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Strains

The isolates from chromoblastomycosis (N=22) and phaeohyphomycosis (n=2) examined in the present study are maintained in the mycoteca of superficial and systemic mycoses at the Instituto Evandro Chagas (IEC) in the state of Pará, Brazil. The representative fungal agents were originally obtained from clinical samples sourced from healthcare units and hospitals within the state of Pará, as evidenced in

Table 1. These agents have already been molecularly identified, and their sequences have been deposited in the GenBank platform of NCBI.

2.2. Morphological Identification

The morphological characteristics of the isolates were assessed through microcultivation on slides, employing lactrimel agar medium, and incubated at 37°C for 14 days. Subsequently, the slides were scrutinized with lactophenol cotton blue staining, utilizing 40x objectives, for the documentation of conidial arrangement organization [

14,

16].

2.3. DNA Extraction

The cultures were subcultured in a tube containing YPD Agar and incubated at 30°C for 14 days for DNA extraction. The extraction process involved collecting approximately 400 mg of fungal mass, which was then added to a 2 mL containing a 450 μL solution composed of 150 μL lysis buffer (SDS), 150 μL homogenization buffer, and 150 μL TE buffer. Glass beads were added, and the microtube was vortexed for 30 minutes. Subsequently, 15 μL of proteinase K were added, and the microtube was incubated in a water bath at 57°C for one hour. Following this, 200 μL of 5 mol/L sodium chloride were added, and the microtube was incubated again at 67°C for 10 minutes.

After incubation, 600 μL of the liquid was transferred to a new microtube and purified using the phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol protocol described by Campos in 2017 [

17]. To achieve enhanced DNA purity, the Bioflux DNA purification kit (Hangzhou Bioer Technology Co. Ltd, Hangzhou, China) was employed in conjunction with the product obtained through the phenol-chloroform methodology, adhering to the procedures delineated in the manufacturer's protocol.

The extracted DNA was quantified using the NanoDrop 2000© spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.®, Waltham, MA, USA). We used the standard value of 1 OD = 50 µg/ml to determine the double-stranded DNA concentration. Only samples with an OD260/280 ratio between 1.7 and 2.0 were included in the study.

2.4. Molecular Identification through Sequencing

Molecular sequencing of the isolates was performed to confirm the previously identified species, focusing on the ITS region, which includes ITS1, 5.8S, and ITS2, using ITS1(F) TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG and ITS4(R) TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC primers. The PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, primer annealing at 55.5°C for 2 minutes, and extension at 72°C for 2 minutes. Finally, a 10-minute extension phase at 72°C was conducted [

18].

The amplification reaction was carried out with 4 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM of each dNTP (deoxynucleotide triphosphate), 1 mM of the primers, 0.1 μL of Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.®, Waltham, MA, USA), 2.5 μL of 10mM/L BSA, and 2 μL of DNA, in a final volume of 25 μL. PCR was performed using a PX2 Thermo Hybaid thermocycler (Artisan Technology Group, Champaign, IL, USA). The amplification product was visualized by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Following electrophoresis, amplicon purification was carried out using the ExoSAP-IT™ PCR Product Cleanup Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.®, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer's recommendations. Sequencing was performed using the BigDye™ Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.®, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions, and the samples were sequenced on an ABI 3130/3130XL Automatic Genetic Analyzer using the dideoxnucleotide chain termination method (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.®, Waltham, MA, USA).

Identification was accomplished by aligning the sequences with those deposited in the GenBank and ISHAM databases, referencing type strains and considering a similarity value greater than 99% for species determination.

2.5. In Silico ITS-RFLP

In order to identify enzymes with the potential for species differentiation among the etiological agents of chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis, an in silico screening was conducted using sequences from the ITS region of the study's target species (N=60) available in the GenBank database. These sequences were downloaded and compiled into a MultiFasta file and aligned with the online software Mafft 7 (

https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/index.html) [

19].

Subsequently, the presence of restriction sites for commercially available enzymes was analyzed using the CLC Sequence Viewer software 8.0

® [

20], with the goal of generating fragments of distinct sizes suitable for species differentiation while ensuring the consistency of restriction sites within the same species. Following the screening and identification of potential enzymes, the online tool NEBcutter v.3

® from New England Biolabs (

https://nc3.neb.com/NEBcutter/) was employed for visualizing the fragmentation pattern in a virtual agarose gel [

21].

2.6. ITS-RFLP

The Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) fragments were amplified using the primer pair ITS1F (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4R 5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′), as previously described. The negative control for the reaction contained all PCR components except the DNA of the agents responsible for chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. PCR products were visualized through electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel using a UV transilluminator. Subsequently, restriction enzyme digestion was conducted in a final volume of 40 μl, following the reaction conditions recommended by the manufacturer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.®, Waltham, MA, USA).

In the single enzymatic digestion, a mixture of 3 μl of Red Buffer (10x) and 1 μl of HhaI enzyme (10U/μl) was added for every 20 μl of PCR product. In the double digestion reaction, 1 μl of HaeIII enzyme (10U/μl), 1 μl of HhaI enzyme (10U/μl), and 3 μl of Red Buffer (10x) were added for every 20 μl of PCR product. A negative control reaction was also performed for each digestion, containing all reagents except the PCR product.

Both reactions were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. The digestion products were then subjected to electrophoresis on a 3% (w/v) agarose gel for 120 minutes, and the fragments were visualized under a UV transilluminator.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Identification and Sequencing of the Isolates

In this study, a total of 24 isolates originating from chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis were utilized. Morphologic identification through micro cultivation analysis allowed for the determination of their genus-level classification, resulting in 21 isolates belonging to the genus Fonsecaea sp., 1 to the genus Exophiala sp., and 1 to the genus Cladophialophora sp.

Molecular identification through sequencing of the ITS region revealed that out of the 24 isolates, 18 were identified as Fonsecaea pedrosoi, 4 as Fonsecaea monophora, 1 as Exophiala dermatitidis, and 1 as Cladophialophora bantiana.

3.2. In Silico Analyses

Through in silico analyses, we have concluded that the enzymes

HhaI and

HaeIII are capable of distinguishing between the species in this study through the restriction of the ITS region. These enzymes can be used in two different assays, the first being a single digestion with

HhaI and the second being a double digestion with

HhaI and

HaeIII. The two proposed assays differ in fragmentation patterns and their ability to distinguish between the species, as shown in

Table 2.

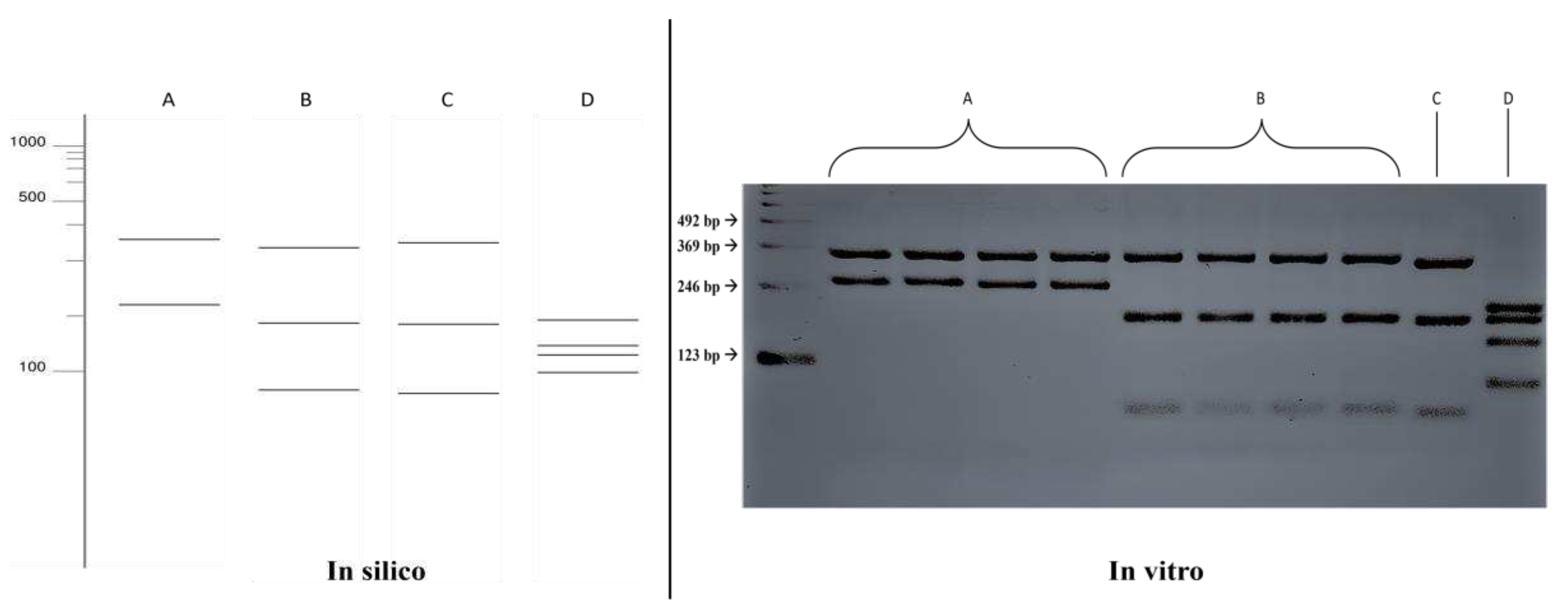

3.3. ITS-RFLP with HhaI

The in silico results of the single digestion with the

HhaI enzyme were compared with the fragmentation patterns obtained in vitro (

Figure 1), where the results were confirmed, allowing for the differentiation between the species

Fonsecaea pedrosoi (352, 219 bp) and

Fonsecaea monophora (330, 188, 53 bp). Fragmentation patterns also differed for the species

Exophiala dermatitidis (193, 193, 135, 98 bp). However, it was not possible to distinguish between the species

Fonsecaea monophora and

Cladophialophora bantiana in the single digestion.

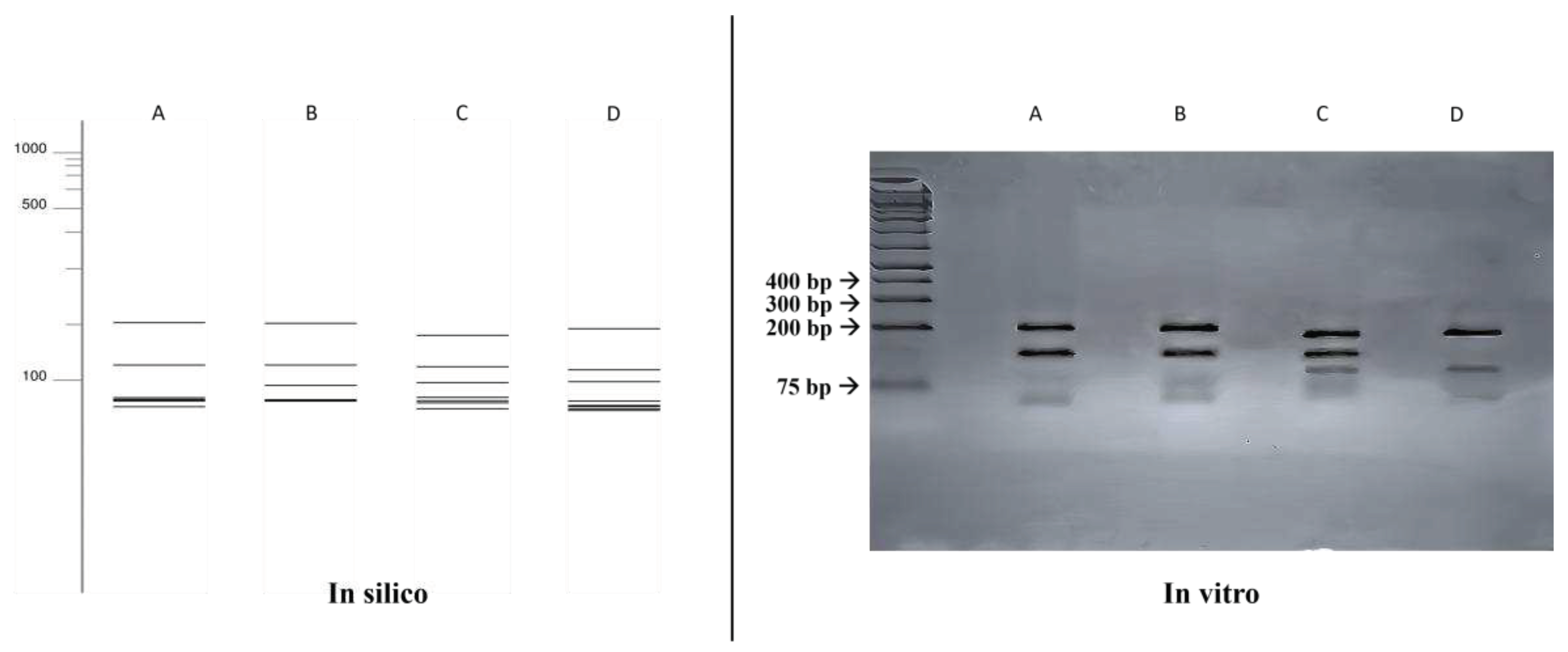

3.4. ITS-RFLP com HhaI e HaeIII

A comparison was made between the double digestion fragmentation patterns obtained in silico and in vitro (

Figure 2), where a similar results to that obtained with the single digestion was achieved for all species, but with a greater power of distinction between the species Fonsecaea monophora (203, 130, 58, 53, 52, 48, 27 bp) and Cladophialophora bantiana (182, 127, 95, 59, 49, 42, 17 bp).

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Identification Methods

The results obtained in both enzyme restriction assays were compared to other identification methods employed in this study (Morphologic and Sequencing). It was observed that the ITS-RFLP method exhibited a higher species identification capability compared to the phenotypic method. Furthermore, the ITS-RFLP method demonstrated a species identification capacity similar to sequencing, as described in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

Infections caused by melanized fungi can significantly impact people's quality of life, leading to discomfort, pain, and, in severe cases, disfigurement. Both chromoblastomycosis (CBM) and phaeohyphomycosis (FEO), when affecting the skin and subcutaneous tissues, can be persistent and challenging to treat, often requiring prolonged therapies and, in some cases, surgical interventions [

1,

8,

22,

23,

24]. In immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS, uncontrolled diabetes, or transplant recipients, agents causing phaeohyphomycosis can disseminate to internal organs and the central nervous system, posing a severe life-threatening risk [

1,

25,

26].

Diagnosing both infections is notoriously challenging and difficult, with chromoblastomycosis typically taking an average of nine years to be correctly identified. In many cases, the causative species remains unidentified [

3] , a crucial concern since recent studies have highlighted variations in pathogenicity, virulence, tropism, and susceptibility to antifungals among these species [

1,

2,

27]. Therefore, identifying the causative agent is essential for a more accurate prognosis [

28].

The lack of identification of these agents in many cases occurs due to the phenotypic and morphological similarity of the species associated with these infections, rendering conventional morphological analysis methods nonspecific. For that reason, applying sequencing and other molecular biology techniques is necessary in most cases [

1,

8,

14,

28].

It is evident that the identification of species causing CBM and FEO poses a challenge to overcome, and the use of molecular techniques can help overcome this barrier. In this context, RFLP emerges as a simple and promising technique for the identification of CBM and FEO agents. Recent studies have shown that this technique serves as a valuable tool for identifying a variety of pathogenic fungal species, such as

Cryptococcus sp., Dermatophytes,

Paracoccidioides sp., and

Candida sp. [

20,

29,

30,

31].

Currently, there is no existing literature on assays for the identification of CBM and FEO agents using RFLP, with only isolated studies of specific primers either do not encompass all currently identified agents or lack sensitivity and specificity [

32].

Due to this gap, the methodology proposed in this study aimed to contribute to the standardization of a species-specific diagnostic method using RFLP of the ribosomal DNA ITS region, known for its high conservation in fungi and currently considered a pan-fungal barcode [

33,

34,

35]. This region is also frequently used for the identification of fungi from the order Chaetothyriales, where the predominant agents of chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis are found [

1,

2,

36,

37].

Furthermore, a recent study published by Fonseca in 2022 [

30], highlighted the efficiency of the ITS region in a simple digestion RFLP assay for identifying species of dermatophytes of the genera

Trichophyton sp. and

Microsporum sp. A comparison between the results obtained through enzymatic restriction and morphological identification showed the greater precision of the molecular technique compared to macroscopic and microscopic analyses, emphasizing the importance of this technique in distinguishing cryptic species of filamentous fungi.

In this context, the molecular identification assays by ITS-RFLP conducted in this study have proven to accurately identify the main species responsible for CBM and FEO, showing greater specificity when compared to morphological analyzes methods. When we compare the RFLP results with those obtained by sequencing, we observe that simple digestion was able to accurately identify 95.8% of the species used in this study, while double digestion accurately identified 100% of the agents, making this technique promising for the molecular identification of these species without the need for sequencing.

Therefore, the use of multiple enzymes resulted in more precise outcomes, attributed to increased fragmentation of the target region, providing better differentiation of genetically close species such as

Fonsecaea monophora,

Fonsecaea pedrosoi, and

Cladophialophora bantiana, all belonging to the same phylogenetic clade [

2].

In this context, ITS-RFLP accurately identified two significant species responsible for chromoblastomycosis:

F. pedrosoi and

F. monophora, both belonging to the genus

Fonsecaea [

2,

38].

Fonsecaea sp. is responsible for over 80% of chromoblastomycosis cases worldwide

3. Specifically,

Fonsecaea pedrosoi is responsible for 84.1% of registered cases in Latin America and the Caribbean [

7].

Besides the agents of chromoblastomycosis, it is possible to identify two species responsible for phaeohyphomycosis. The first is

Exophiala dermatitidis, a causative agent of cutaneous, subcutaneous, and invasive infections [

26,

39,

40], which, in severe cases, can affect the central nervous system [

41]. The second identifiable species is

Cladophialophora bantiana, a causative agent of PHM with high lethality due to invasive infections, mainly affecting the central nervous system of immunocompromised and post-transplant patients [

25,

40,

41,

42].

5. Conclusions

Our results introduce a novel molecular identification method based on ITS-RFLP for the two major causative agents of chromoblastomycosis worldwide and for two significant agents causing opportunistic and invasive phaeohyphomycosis.

As the causative agents of these infections differ in terms of virulence, pathogenicity, tropism, and susceptibility to antifungals, necessitating their identification for a more accurate prognosis of the infection and guide appropriate therapy, preventing serious complications such as infection dissemination or an inadequate treatment response.

In this context, the identification of these species through ITS-RFLP expands the range of molecular identification possibilities for these agents, providing rapid results at a lower cost compared to sequencing. This enables the improvement of accuracy and speed in diagnosis, ensuring proper management of these fungal infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.M.S., R.O., R.C.S. and S.H.M.S.; data curation E.P.T.E.S. and G.S.M.S.; formal analysis, G.S.M.S. and A.B.S.; supervision, S.H.M.S.; writing—original draft, G.S.M.S.; writing—review & editing, R.O., L.F.F. and S.H.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Evandro Chagas Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data were reporetd in this study.

Acknowledgments

We express gratitude to the Evandro Chagas Institute, Ananindeua, PA, Brazil, for providing the necessary supplies, laboratory infrastructure, and strains of interest for the execution of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arcobello, J.T.; Revankar, S.G. Phaeohyphomycosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Telles, F.; de Hoog, S.; Santos, D.W.C.L.; Salgado, C.G.; Vicente, V.A.; Bonifaz, A.; Roilides, E.; Xi, L.; Azevedo, C.d.M.P.e.S.; da Silva, M.B.; et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 233–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.W.C.L.; Azevedo, C.d.M.P.e.S.d.; Vicente, V.A.; Queiroz-Telles, F.; Rodrigues, A.M.; de Hoog, G.S.; Denning, D.W.; Colombo, A.L. The global burden of chromoblastomycosis. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enbiale, W.; Bekele, A.; Manaye, N.; Seife, F.; Kebede, Z.; Gebremeskel, F.; van Griensven, J. Subcutaneous mycoses: Endemic but neglected among the Neglected Tropical Diseases in Ethiopia. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Who. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A strategic framework for integratedcontrol and management of skin-related neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2022.

- Agarwal, R.; Singh, G.; Ghosh, A.; Verma, K.K.; Pandey, M.; Xess, I. Chromoblastomycosis in India: Review of 169 cases. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, A.; Siqueira, N.P.; Nery, A.F.; Cavalcante, L.R.d.S.; Hagen, F.; Hahn, R.C. Chromoblastomycosis in Latin America and the Caribbean: Epidemiology over the Past 50 Years. Medical Mycology. Oxford University Press December 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zheng, H.-L.; Mei, H.; Lv, G.-X.; Liu, W.-D.; Li, X.-F. Phaeohyphomycosis in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 895329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Bertolotti, A.; Barreau, A.; Klisnick, J.; Tournebize, P.; Borgherini, G.; Zemali, N.; Jaubert, J.; Jouvion, G.; Bretagne, S.; et al. From Phaeohyphomycosis to Disseminated Chromoblastomycosis: A Retrospective Study of Infections Caused by Dematiaceous Fungi. Med Mal Infect 2018, 48, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhi, H.; Shen, H.; Lv, W.; Sang, B.; Li, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xia, X. Chromoblastomycosis: A case series from Eastern China. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passero, L.F.D.; Cavallone, I.N.; Belda, W. Reviewing the Etiologic Agents, Microbe-Host Relationship, Immune Response, Diagnosis, and Treatment in Chromoblastomycosis. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, A.C.; Bittencourt, M.d.J.S. Chromoblastomycosis: An etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An. Bras. de Dermatol. 2018, 93, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revankar, S.G.; Sutton, D.A. Melanized Fungi in Human Disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 884–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, O.C.; León-Cachón, R.B.R.; Pérez-Maya, A.A.; Aguirre-Garza, M.; Moreno-Treviño, M.G.; González, G.M. Phenotypic and molecular identification of Fonsecaea pedrosoi strains isolated from chromoblastomycosis patients in Mexico and Venezuela. Mycoses 2015, 58, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienvenu, A.-L.; Picot, S. Mycetoma and Chromoblastomycosis: Perspective for Diagnosis Improvement Using Biomarkers. Molecules 2020, 25, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoog, G.S.; Guarro, J.; Gené, J.; Figueras, M.J. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2°ed.; Utrech, The Netherlands and Universitat Rovira i Virgili Reus, Spain, 2000, pp. 560-680.

- Monteiro, R.C. Epidemiologia Molecular e Caracterização fenotípica de Fungos Demáceos Agentes de Cromoblastomicose no Estado do Pará, com Relato de Fungos Neurotrópicos na Região Amazônica. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Pará, Brasil, 2017.

- Sun, J.; Najafzadeh, M.J.; Ende, A.H.G.G.v.D.; Vicente, V.A.; Feng, P.; Xi, L.; De Hoog, G.S. Molecular Characterization of Pathogenic Members of the Genus Fonsecaea Using Multilocus Analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings Bioinform. 2018, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, T.N.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Hahn, R.C.; de Camargo, Z.P. Identifying Paracoccidioides Phylogenetic Species by PCR-RFLP of the Alpha-Tubulin Gene. Med Mycol. 2016, 54, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, T.; Posfai, J.; Roberts, R.J. NEBcutter: A program to cleave DNA with restriction enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3688–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, A.M.; Fraser, M.; Patterson, Z.; Linton, C.J.; Palmer, M.; Johnson, E.M. Fungal Infections of Implantation: More Than Five Years of Cases of Subcutaneous Fungal Infections Seen at the UK Mycology Reference Laboratory. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendrasoa, F.A.; Razanakoto, N.H.; Rakotoarisaona, M.F.; Andrianarison, M.; Raharolahy, O.; Rasamoelina, T.; Ranaivo, I.M.; Sata, M.; Ratovonjanahary, V.; Maubon, D.; et al. Clinical aspects of previously treated chromoblastomycosis: A case series from Madagascar. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariani, T.; Rizal, Y.; Ledika Veroci, R. Clinical and Mycological Spectrum of Chromoblastomycosis; 2023; Vol. 33.

- Revankar, S.G. Phaeohyphomycosis in Transplant Patients. J. Fungi 2016, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Xu, J.; Su, Q.; Chen, Y. Exophiala dermatitis and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2019, 112, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, L.; Jia, G.; Tan, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, L. Analysis of the synergistic antifungal activity of everolimus and antifungal drugs against dematiaceous fungi. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1131416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, R.A.; Brito-Santos, F.; Figueiredo-Carvalho, M.H.G.; Silva, J.V.d.S.; Gutierrez-Galhardo, M.C.; Valle, A.C.F.D.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M.; Trilles, L.; Meyer, W.; Freitas, D.F.S.; et al. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility profiles of clinical strains of Fonsecaea spp. isolated from patients with chromoblastomycosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, E.; Barião, P.H.G.; Kress, M.R.v.Z.; Vilar, F.C.; Santana, R.d.C.; Gaspar, G.G.; Martinez, R. Cryptococcosis by Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii Species Complexes in non-HIV-Infected Patients in Southeastern Brazil. Rev. da Soc. Bras. de Med. Trop. 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, L.A.V.; Araújo, M.A.S.; Silva, D.M.W.; Maranhão, F.C.D.A. ITS-RFLP optimization for dermatophyte identification from clinical sources in Alagoas (Brazil) versus phenotypic methods. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 16, 1773–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecha, G.; Montes, K.; Ortiz, B.; Galindo, C.; Braham, S. Identification of Cryptic Species of Four Candida Complexes in a Culture Collection. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maubon, D.; Garnaud, C.; Ramarozatovo, L.S.; Fahafahantsoa, R.R.; Cornet, M.; Rasamoelina, T. Molecular Diagnosis of Two Major Implantation Mycoses: Chromoblastomycosis and Sporotrichosis. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajarningsih, N.D. Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) as Dna Barcoding to Identify Fungal Species: A Review. Squalen Bull. Mar. Fish. Postharvest Biotechnol. 2016, 11, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.T.V.; Irinyi, L.; Chen, S.C.A.; Sorrell, T.C.; Meyer, W. The ISHAM Barcoding of Medical Fungi Working Group Dual DNA Barcoding for the Molecular Identification of the Agents of Invasive Fungal Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Adamowicz, S.J.; Chain, F.J.; Clare, E.L.; Deiner, K.; Dincă, V.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M.; Hausmann, A.; Hogg, I.D.; Kekkonen, M.; et al. Fungal DNA barcoding. Genome 2016, 59, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réblová, M.; Untereiner, W.A.; Réblová, K. Novel Evolutionary Lineages Revealed in the Chaetothyriales (Fungi) Based on Multigene Phylogenetic Analyses and Comparison of ITS Secondary Structure. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, M.M.; Moreno, L.F.; Stielow, B.; Muszewska, A.; Hainaut, M.; Gonzaga, L.; Abouelleil, A.; Patané, J.S.L.; Priest, M.; Souza, R.; et al. Exploring the genomic diversity of black yeasts and relatives (Chaetothyriales, Ascomycota). Stud. Mycol. 2017, 86, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafzadeh, M.J.; Gueidan, C.; Badali, H.; Ende, A.H.G.G.V.D.; Xi, L.; De Hoog, G.S. Genetic Diversity and Species Delimitation in the Opportunistic Genus Fonsecaea. Med Mycol. 2009, 47, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usuda, D.; Higashikawa, T.; Hotchi, Y.; Usami, K.; Shimozawa, S.; Tokunaga, S.; Osugi, I.; Katou, R.; Ito, S.; Yoshizawa, T.; et al. Exophiala dermatitidis. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 7963–7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejarano, J.I.C.; Santos, A.M.d.L.; Saldaña, D.C.; Lucio, M.Z.; Cavazos, S.P.; Villaseñor, F.E.; de la O Cavazos, M.E.; Aparicio, D.N.V. Pediatric Phaeohyphomycosis: A 44-Year Systematic Review of Reported Cases. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2022, 12, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Govic, Y.; Demey, B.; Cassereau, J.; Bahn, Y.-S.; Papon, N. Pathogens infecting the central nervous system. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, V.; Hallur, V.; Velvizhi, S.; Rajendran, T. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis due to Cladophialophora bantiana: Case report and systematic review of cases. Infection 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).