Submitted:

20 December 2023

Posted:

25 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Multi-Modal Cancer Rehabilitation

The Cancer Landscape in Sheffield

Development of the Active Together Service

| Professional role category 1 (clinical) | Number |

|---|---|

| Anaesthetist | 4 |

| Surgeon | 6 |

| Clinical nurse specialist | 4 |

| Oncologist | 4 |

| Exercise medicine consultant | 2 |

| Physiotherapist | 5 |

| Occupational therapist | 1 |

| Dietitian | 4 |

| Clinical psychologist | 3 |

| Total | 29 |

| Professional role category 2 (non clinical) | |

| Researcher | 2 |

| Fitness professional | 3 |

| Charitable sector (Cancer Support Centre, Cavendish Centre) | 2 |

| Other (cancer alliance, prehabilitation lead) | 4 |

| Total | 11 |

The Content of the Active Together Service

Referral

The Initial Patient Needs’ Assessment

| Rehabilitation discipline | Measure |

|---|---|

| Physical activity needs criteria |

|

| Nutritional needs criteria |

|

| Psychological needs criteria |

|

|

Patient need (Support provided) |

Intervention for each level of need (What?, Who?, Where?) |

|

Low complexity/need (Universal) Patient is healthy, with no additional physical, nutritional and/or psychological risk factors and requires no specialist support. |

What? |

Physical activity

| |

| Who? | |

Physical activity

| |

| Where? | |

| |

|

Moderate complexity/need (Targeted) Patient has some physical, nutritional and/or psychological risk factors and requires monitoring and some specialist support and monitoring. |

What? |

Physical activity

| |

| Who? | |

Physical activity

| |

| Where? | |

| |

|

High complexity/need (Specialist) Patient has significant physical, nutritional and/or psychological risk factors and requires frequent specialist support. |

What? |

Physical activity

Access to dietitian 1 x per week telephone or face-face) Psychological Alleviate distress from cancer and prepare patients psychologically for treatment | |

| Who? | |

Physical activity

| |

| Where? | |

|

Active Together Service Delivery Style and Behaviour Change Approach

| Intervention function | Behaviour Change Technique (BCT no. (BCTTv1)) | Example of application within the multi-modal Active Together service |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Information about emotional consequences (5.6) |

|

| Feedback on behaviour (2.2) |

|

|

| Self-monitoring of behaviour (2.3) |

|

|

| Reduce negative emotions (11.2) |

|

|

| Information about health consequences (5.1) |

|

|

| Persuasion | Credible source (9.1) |

|

| Information about emotional consequences (5.6) |

|

|

| Feedback on behaviour (2.2) |

|

|

| Verbal persuasion and capability (15.1) |

|

|

| Training | Demonstration of the behaviour (6.1) |

|

| Instruction on how to perform a behaviour (4.1) |

|

|

| Feedback on behaviour (2.2) |

|

|

| Self-monitoring of behaviour (2.3) |

|

|

| Graded tasks (8.7) |

|

|

| Behavioural practice/rehearsal (8.1) |

|

|

| Biofeedback (2.6) |

|

|

| Environmental restructuring | Adding objects to the environment (12.5) |

|

| Reduce negative emotions (11.2) |

|

|

| Modelling | Demonstration of the behaviour (6.1) |

|

| Enablement | Goal setting (behaviour) (1.1) |

|

| Goal setting (outcome) (1.3) |

|

|

| Adding objects to the environment (12.5) |

|

|

| Problem-solving (1.2) |

|

|

| Action planning (1.4) |

|

|

| Self-monitoring of behaviour (2.3) |

|

|

| Generalisation of target behaviour (8.6) |

|

|

| Review behaviour goal(s) (1.5) |

|

|

| Review outcome goal(s) (1.7) |

|

|

| Social support (emotional) (3.3) |

|

Phases of the Rehabilitation Continuum

Phase 1: Prehabilitation

Phase 2: Maintenance Rehabilitation

Phase 3: Restorative Rehabilitation

Phase 4: Supportive Rehabilitation

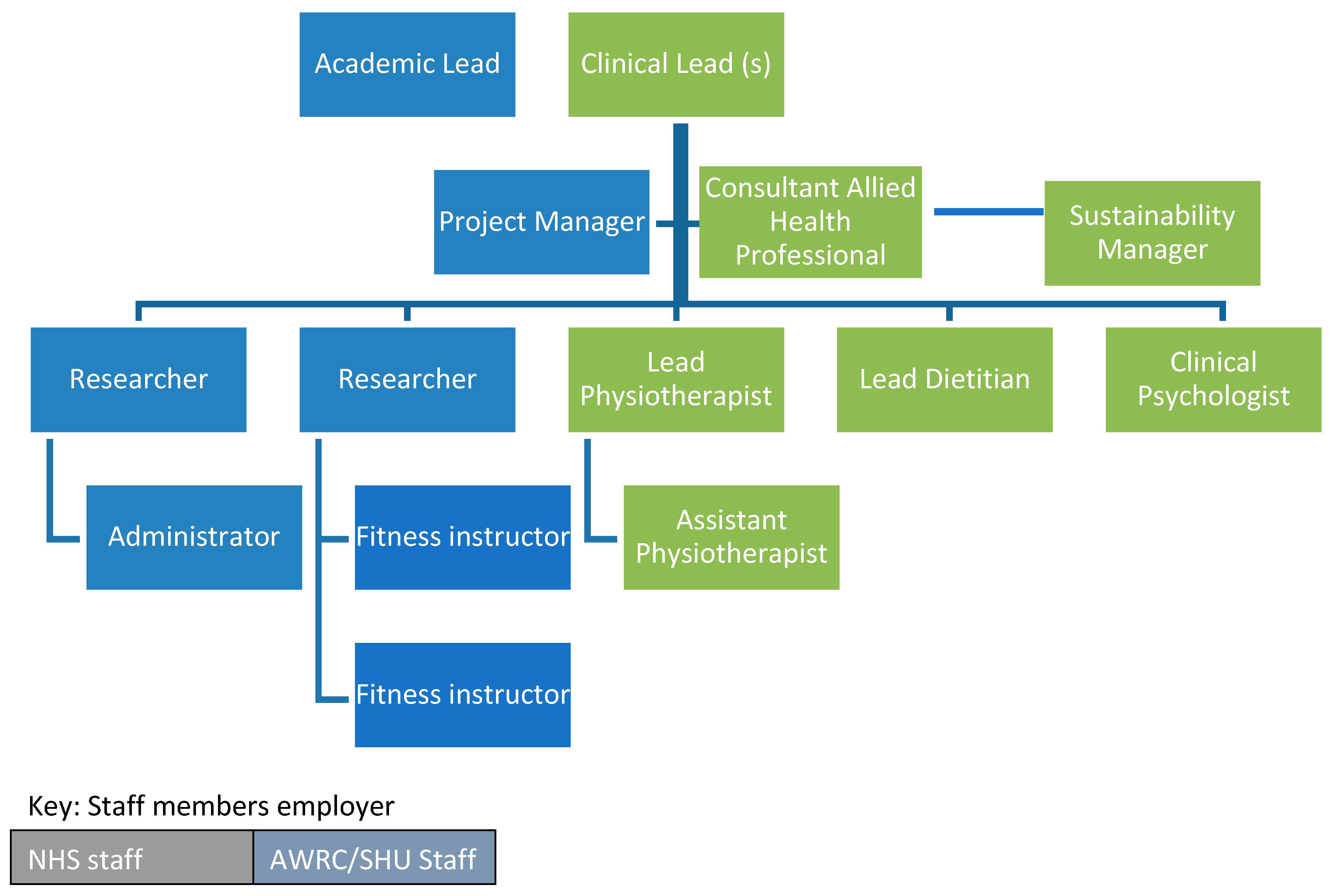

Active Together Workforce

Pilot Phase

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Integrated care system guidance for cancer rehabilitation A guide to reducing variation and improving outcomes in cancer rehabilitation in london. 2019.

- Rehabilitation. www.who.int Web site. Updated 2021. Accessed 01/07/, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation.

- Pizzoli, S.F.M.; Renzi, C.; Arnaboldi, P.; Russell-Edu, W.; Pravettoni, G. From life-threatening to chronic disease: Is this the case of cancers? A systematic review. Cogent psychology 2019, 6(1). Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23311908.2019.1577593. [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.K. Integrating rehabilitation into the cancer care continuum. PM & R 2017, 9 (9 Suppl 2), S291–S296. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.07.075. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormie, P.; Trevaskis, M.; Thornton-Benko, E.; Zopf, E.M. Exercise medicine in cancer care. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2020, 49, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, N.L.; Brown, J.C.; Schwartz, A.L.; et al. An exercise oncology clinical pathway: Screening and referral for personalized interventions. Cancer. 2020, 126, 2750–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishita, S.; Hamaue, Y.; Fukushima, T.; Tanaka, T.; Fu, J.B.; Nakano, J. Effect of exercise on mortality and recurrence in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integrative Cancer Therapies 2020, 19, 153473542091746–1534735420917462. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1534735420917462. [CrossRef]

- Schwedhelm, C.; Boeing, H.; Hoffmann, G.; Aleksandrova, K.; Schwingshackl, L. Effect of diet on mortality and cancer recurrence among cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutrition Reviews. 2016, 74, 737–748. Available online: https://wwwncbinlmnihgov/pubmed/27864535. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormie, P.; Atkinson, M.; Bucci, L.; et al. Clinical oncology society of australia position statement on exercise in cancer care. Medical Journal of Australia. 2018, 209, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormie, P.; Trevaskis, M.; Thornton-Benko, E.; Zopf, E.M. Exercise medicine in cancer care. Australian journal of general practice. 2020, 49, 169–174. Available online: https://search.informit.org/documentSummary;dn=053010821856031;res=IELIAC. [CrossRef]

- Achieving world-class cancer outcomes: Taking the strategy forward.. 2016. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/cancer-strategy.pdf.

- NHS. The NHS long term plan.. 2019:61.

- Silver, J.K.; Raj, V.S.; Fu, J.B.; Wisotzky, E.M.; Smith, S.R.; Kirch, R.A. Cancer rehabilitation and palliative care: Critical components in the delivery of high-quality oncology services. Support Cancer Care 23, 3633–3643. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, J.H. Adaptive rehabilitation in cancer. Postgraduate medicine. 1980, 68, 145–153. Available online: http://wwwtandfonlinecom/doi/abs/101080/00325481198011715495. [CrossRef]

- Sleight, A.G.; Gerber, L.H.; Marshall, T.F. A systematic review of functional outcomes in cancer rehabilitation research. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35104445. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julie KSilver Nicole LStout Jack Fu Mandi Pratt-Chapman Pamela, J. Hajlock, Raman Sharma. The state of cancer rehabilitation in the united states. Journal of Cancer Rehabilitation 2018, 1, 1–8. Available online: https://doaj.org/article/51b8ea8ec4ac4199a905469fa35c5394.

- Smith, S.R.; Zheng, J.Y.; Silver, J.; Haig, A.J.; Cheville, A. Cancer rehabilitation as an essential component of quality care and survivorship from an international perspective. Disability and rehabilitation. 2020, 42, 8–13. Available online: https://wwwtandfonlinecom/doi/abs/101080/0963828820181514662. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennett, A.; Peiris, C.; Shields, N.; Taylor, N. From cancer rehabilitation to recreation: A coordinated approach to increasing physical activity. Physical Therapy. 2020, 100, 2049–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimmett, C.; Bates, A.; West, M. SafeFit trial: Virtual clinics to deliver a multimodal intervention to improve psychological and physical well-being in people with cancer. protocol of a COVID-19 targeted non-randomised phase III trial. BMJ Open, 2021; 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Merchant, Z.; Rowlinson, K. Implementing a system-wide cancer prehabilitation programme: The journey of greater manchester's ‘Prehab4cancer’. European journal of surgical oncology. 2021, 47, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer incidence. Cancer Data Web site. Accessed 16/02/, 2022. Available online: https://www.cancerdata.nhs.uk/incidence_and_mortality.

- Local Cancer Intelligence. Survival in NHS sheffield CCG. Macmillan Cancer Support Web site. Available online: https://lci.macmillan.org.uk/England/03n/survival.

- Charles, A. Integrated care systems explained: Making sense of systems, places and neighbourhoods. Kings Fund. 2021.

- Humphreys, L.; Crank, H.; Frith, G.; Speake, H.; Reece, L.J. Bright spots, physical activity investments that work: Active everyday, sheffield’s physical activity service for all people living with and beyond cancer. British journal of sports medicine. 2019, 53, 837–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys, L.; Frith, G.; Humphreys, H. Evaluation of a city-wide physical activity pathway for people affected by cancer: The active everyday service. Support Care Cancer. 2023, 31, 101. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00520-022-07560-y. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys, L.; Crank, H.; Dixey, J.; Greenfield, D.M. An integrated model of exercise support for people affected by cancer: Consensus through scoping. Disability and rehabilitation. 2020, 44, 1113–1122. Available online: http://wwwtandfonlinecom/doi/abs/101080/0963828820201795280. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.; Crank, H.; Humphreys, H.; Fisher, P.; Greenfield, D.M. Time to embed physical activity within usual care in cancer services: A qualitative study of cancer healthcare professionals’ views at a single centre in england. Disability and Rehabilitation 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.; Crank, H.; Humphreys, H.; Fisher, P.; Greenfield, D.M. Allied health professional's self-reported competences and confidence to deliver physical activity advice to cancer patients at a single centre in england. Disability and rehabilitation 2022, 1–7. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09638288.2022.2143580. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennett, A.M.; Zappa, B.; Wong, R.; Ting, S.B.; Williams, K.; Peiris, C.L. Bridging the gap: A pre-post feasibility study of embedding exercise therapy into a co-located cancer unit. Support Care Cancer. 2021, 29, 6701–6711 https://linkspringercom/article/101007/s00520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, R.M.; Street, R.L. The values and value of patient-centered care. Annals of family medicine. 2011, 9, 100–103. Available online: https://www.clinicalkey.es/playcontent/1-s2.0-S1544170911600450. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Wong, M.L.; Hayhurst, C.; Watson, P.; Morrison, C. Designing services for frequent attenders to the emergency department: A characterisation of this population to inform service design. Clinical medicine (London, England). 2016, 16, 325–329. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27481374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, J.; Foster, J.; Poulter, E. Increasing the frequency of physical activity very brief advice for cancer patients. development of an intervention using the behaviour change wheel. Public Health. 2016, 133, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macmillan Cancer Support, Royal College of Anaesthetists, National Institute for Health Research. Principles and guidance for prehabilitation within the management and support of people with cancer.. 2019.

- Ormel, H.L.; van der Schoot, G.G.F.; Sluiter, W.J.; Jalving, M.; Gietema, J.A.; Walenkamp, A.M.E. Predictors of adherence to exercise interventions during and after cancer treatment: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology. 2018, 27, 713–724. Available online: https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:pure.rug.nl:publications%2F1846a8d8-34b6-4f97-a2ba-27499602a66a. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of medical research council guidance. BMJ, 2021; 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmett, C.; Bradbury, K.; Dalton, S.O. The role of behavioral science in personalized multimodal prehabilitation in cancer. Frontiers in psychology 2021, 12, 634223. Available online: https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:tilburguniversity.edu:publications%2F98562b1f-7b34-4e73-8abf-64d8d5ed2419. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCourt, O.; Fisher, A.; Ramdharry, G. PERCEPT myeloma: A protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial of exercise prehabilitation before and during autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. BMJ Open. 2020, 10, e033176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.R.; Steed, L.; Quirk, H. Interventions for promoting habitual exercise in people living with and beyond cancer. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018, 2018, CD010192. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010192.pub3. [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science : IS. 2011, 6, 42. Available online: https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl:publications%2F1f2b8c2a-86b8-42b3-b106-2f2a5387283d. [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. ann behav med. 2013, 46, 81–95. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6. [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Breckons, M.; Cotterell, P. Cancer survivors’ self-efficacy to self-manage in the year following primary treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 11–19. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11764-014-0384-0. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, S.; Fu, M.R.; Lyons, K.; Wood, K.C.; Wood Magee, L.J. The role of exercise self-efficacy in exercise participation among women with persistent fatigue after breast cancer: A mixed-methods study. Physical therapy. 2023, 103, 1. Available online: https://wwwncbinlmnihgov/pubmed/36222153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, E.; Larsen, J.; Schempp, T.; Jonsson, L.; Winterling, J. Patients' goals related to health and function in the first 13 months after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Support Care Cancer. 2012, 20, 2025–2032. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00520-011-1310-x. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.; Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. New York: Guildford; 2002.

- Olsen, C.F.; Debesay, J.; Bergland, A.; Bye, A.; Langaas, A.G. What matters when asking, “what matters to you?” — perceptions and experiences of health care providers on involving older people in transitional care. BMC Health Services Research. 2020, 20, 317. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32299424. [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.; Baima, J. Cancer prehabilitation: An opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2013, 92, 715–727. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23756434. [CrossRef]

- Ormel, H.L.; van der Schoot, G.G.F.; Sluiter, W.J.; Jalving, M.; Gietema, J.A.; Walenkamp, A.M.E. Predictors of adherence to exercise interventions during and after cancer treatment: A systematic review. Psycho-oncology (Chichester, England). 2018, 27, 713–724. Available online: https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:pure.rug.nl:publications%2F1846a8d8-34b6-4f97-a2ba-27499602a66a. [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.N.; McAuley, E.; Trinh, L. Physical activity programming and counseling preferences among cancer survivors: A systematic review. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2018, 15, 48. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29879993. [CrossRef]

- Parke, S.C.; Ng, A.; Martone, P. Translating 2019 ACSM cancer exercise recommendations for a physiatric practice: Derived recommendations from an international expert panel. PM & R 2548. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2548409171. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, C.A.; Farragher, J.F.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Ding, Q.; Mckinnon, G.P.; Cheung, W.Y. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: A systematic review and evaluation of intervention content and theories. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, R.J. The move more plan - A framework for increasing physical activity in sheffield 2015-2020. 2020.

- Speake, H.; Copeland, R.J.; Till, S.H.; Breckon, J.D.; Haake, S.; Hart, O. Embedding physical activity in the heart of the NHS: The need for a whole-system approach. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 939–946. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-016-0488-y. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, R.J.; Lowe, A. How our pioneering new healthcare model is helping people stay active. Available online: https://www.shu.ac.uk/research/in-action/projects/move-moreUpdated 2021. Accessed 01/07/, 2023.

- Speake, H.; Copeland, R.J.; Till, S.H.; Breckon, J.D.; Haake, S.; Hart, O. Embedding physical activity in the heart of the NHS: The need for a whole-system approach. Sports Medicine. 2016, 46, 939–946. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40279-016-0488-y. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).