1. Introduction

Since the introduction of the first antibiotics, in the early 1900s, the modern medicine has greatly changed, positively affecting and extending the average human lifespan. The period between 1950 and 1960 has been a golden age for antibiotics discovery and, till to year 2000, antibiotics’ production has significantly increased [

1], due to their use for the treatment of several pathologies other than infectious diseases, such as cancer treatment, organ transplants and open-heart surgery [

2]. Besides human use, antibacterial drugs have also been adopted for nontherapeutic applications, such as growth promoters for animals to improve feed efficiency [

3]. Their extending use for both human and animal purposes has resulted in the rapid rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), leading to the impossibility to effectively treat numerous infections [

4]. AMR is defined as the presence of a genetically acquired or mutated resistance mechanism, categorizing the pathogen as resistant or susceptible based on the application of a set cut-off in a phenotypic laboratory test [

5]. To date, antimicrobial resistance is a significant global health concern, as it could cause prolonged illnesses as well as higher mortality rates and increased healthcare costs. Due to these challenges, multifaced national and international strategies are recommended to improve infection prevention and control practices, thus reducing the antibiotics request and improving the production of new ones. The development of new active molecules raises the question related to the need to identify target compounds either with new modes of action or with new target interactions and established mechanism of action [

6]. Among the several solutions available, one of the options is the synthesis of new pharmacophores starting from piperazine or morpholine core units.

Piperazine ranks as the third most common

N-heterocycle appearing in small pharmaceutical molecules and it still continues to be a privileged structural motif in drug discovery [

7]. It consists of a six-membered ring with two nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 4 in the ring. Piperazine is a freely water and ethylene glycol soluble compound and the presence of two nitrogen atoms confers weak basic properties (pK

b of 5.3 and 9.7 at 25 °C) [

8]. Most of the drugs containing piperazine scaffold are substituted either on both or on a single nitrogen atom. Moreover, piperazine often serves as a connecting moiety, linking two segments of a drug, or as an additional component to fine-tune the physicochemical characteristics of the drug. In general, its high polar surface area and relative structural rigidity allow to improve absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties [

9]. As regard to morpholine, it is structurally related to piperazine by the substitution of one

N atom with oxygen in the six-membered ring. Although morpholine is a relatively strong base (pK

b of 5.3), ring substitution could increase compound basicity as pK

b could varies between 8.0 and 6.1 [

10]. While the lipophilicity of molecules containing morpholine scaffold primarily relies on their specific substitutions, the ring itself exhibits well-balanced lipophilic-hydrophilic properties, demonstrating desirable characteristics for pharmaceutical applications. Both piperazine and morpholine are versatile building blocks that can be easily modified and functionalized to create several chemical structures, with enhanced efficacy, specificity, and pharmacokinetic properties. Their derivatives have been recognized for a wide array of therapeutical effects, encompassing analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antihyperlipidemic properties, as well as exhibiting anticancer and antimicrobial properties [

11,

12]. Therefore, they can serve as starting point for designing new antibiotics with improved potency and expanded spectrum of activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

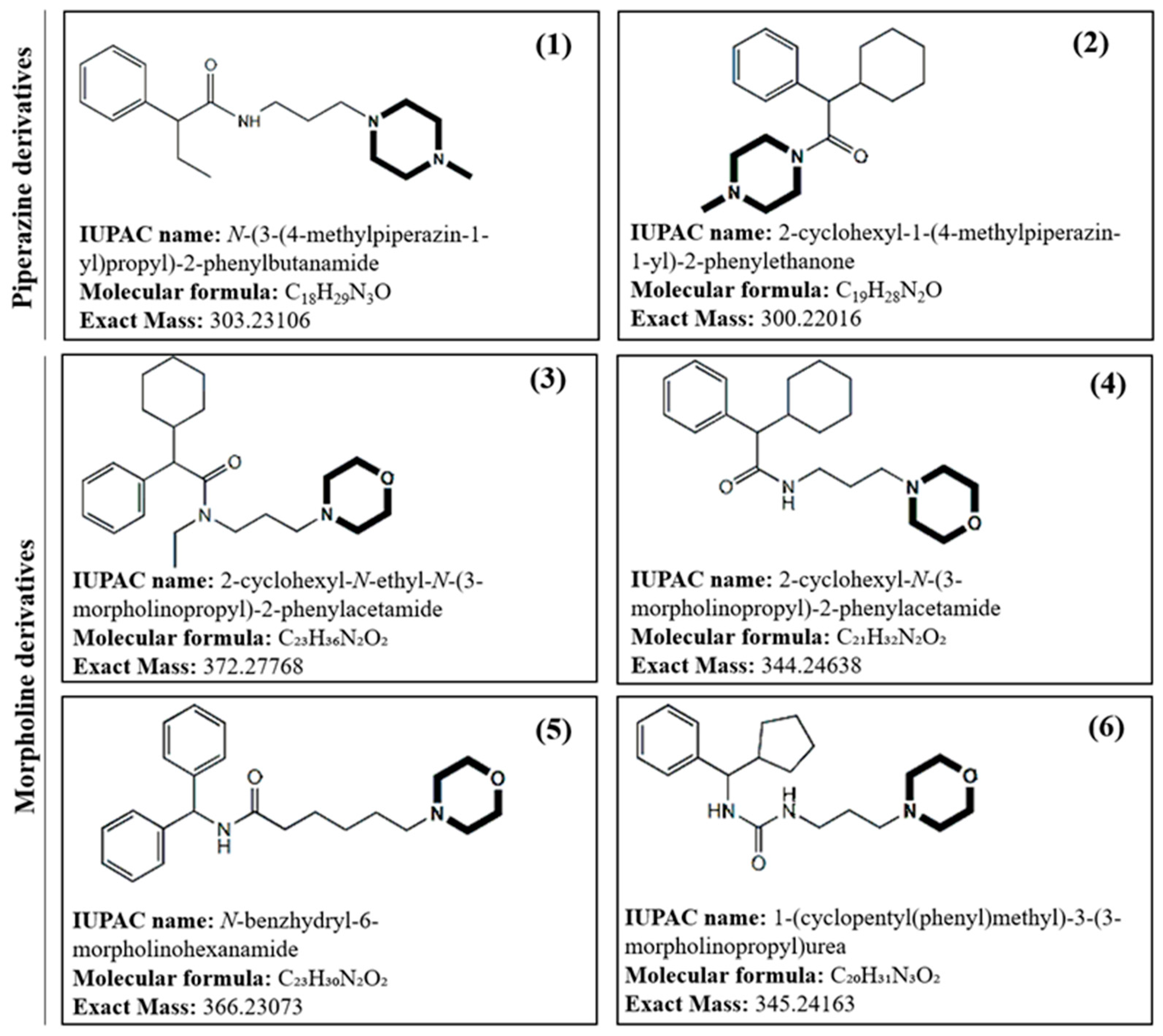

Due to the current demand for new antimicrobials able to address life-threatening infections caused by the worldwide dissemination of multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens, in this work new piperazine and morpholine derivatives (

Figure 1) with potential antibacterial activity have been synthetized, structurally characterized by mass spectrometry, both low and high-resolution MS, and evaluated for their antibacterial activity.

2. Results

2.1. Mass Spectrometric characterization of Piperazine derivatives

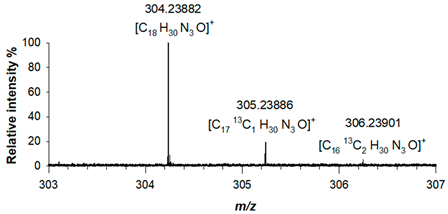

ESI (+)-FT ICR MS spectra acquired for piperazine derivative (1) showed a protonated adduct, [M+H]

+, at

m/z 304.23882 (C

18H

30N

3O

+, RMS error 1.6 ppm), alongside with two other mass signals corresponding to the two isotopologues, A+1 and A+2 at

m/z 305.23886 (C

1713C

1H

30N

3O

+, RMS error 1.7 ppm) and

m/z 306.23901 (C

1613C

2H

30N

3O

+, RMS error 2.2 ppm), respectively, due to the presence of

13C isotopes. The correctness of this assignment was verified both in terms of mass accuracy and relative intensity of isotopologues signals (

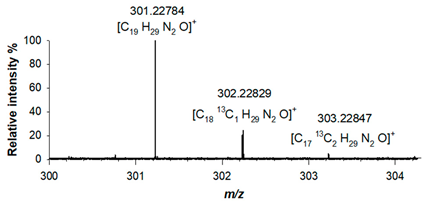

Table 1). For derivative (2), the elemental composition was confirmed by its accurate mass, as a protonated adduct was observed at

m/z 301.22784 (C

19H

29N

2O

+; RMS error 1.3 ppm), alongside with signals related to isotopologues A+1 at

m/z 302.22829 (C

1813C

1H

29N

2O

+; RMS error 2.8 ppm) and A+2 at

m/z 303.22847 (C

1713C

2H

29N

2O

+; RMS error 3.4ppm) (

Table 1).

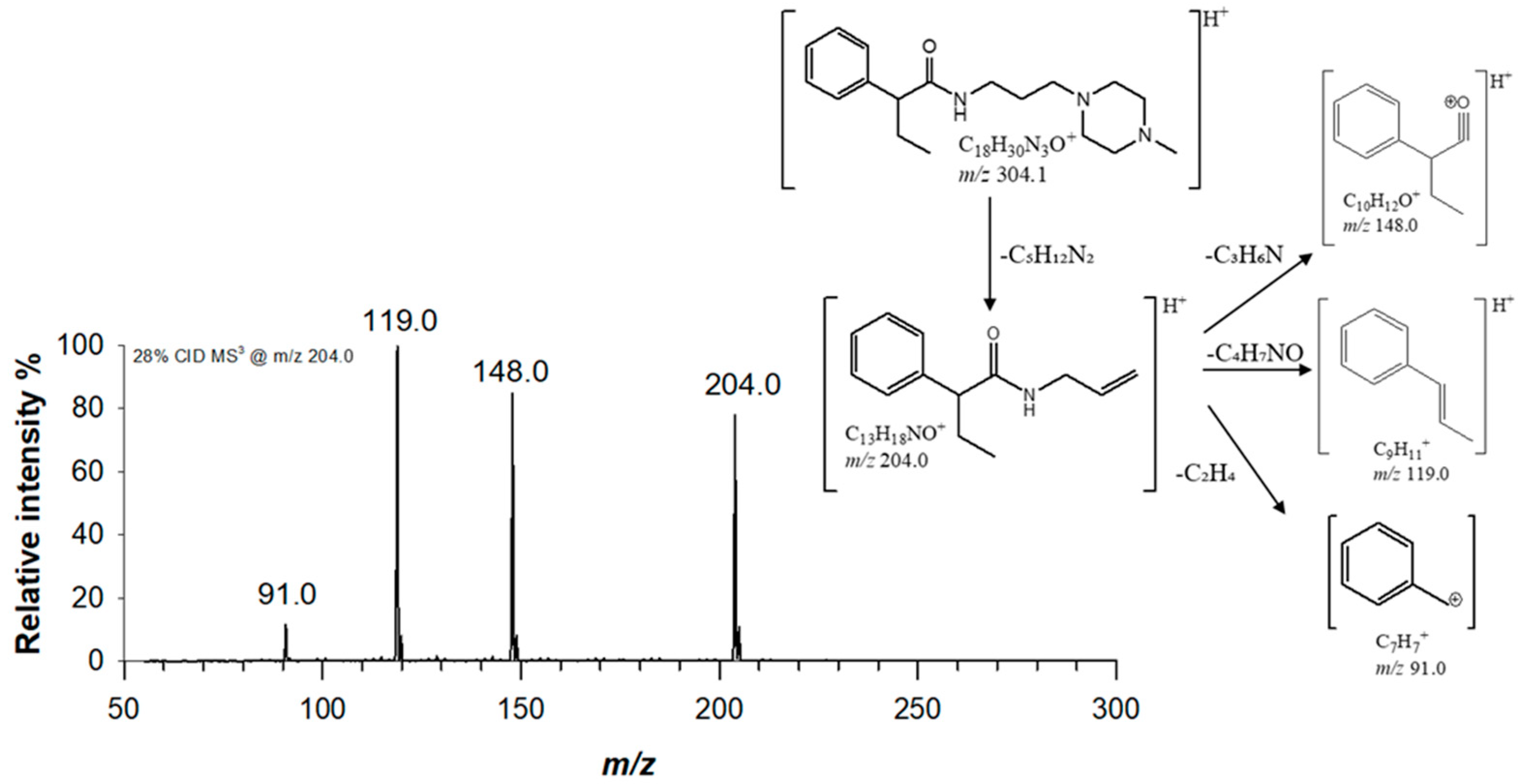

The fragmentation behaviour of both piperazine compounds was studied by collision induced dissociation (CID) using a linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ-MS), thus facilitating structure elucidation based on MS

n scans. For derivative (1), a single signal at

m/z 204.0 was obtained by fragmenting precursor ion at

m/z 304.1, which was isolated with a window of 6

m/z in order to include the whole isotopologue cluster of the protonated molecule. A collision energy of 7.4 eV was applied for MS/MS studies. Base peak at

m/z 204.0 ([C

13H

18NO]

+) was due to the characteristic neutral loss of

N-methylpiperazine (−100 Da, C

5H

12N

2) [

13]. (1) structure was confirmed by MS

3 experiments, by fragmenting ion at

m/z 204.0 with a collision energy of 9.8 eV. The obtained MS

3 spectra is reported in

Figure 2, alongside with the proposed fragmentation scheme. Two major fragments were observed at

m/z 119.0 (C

9H

11+) and

m/z 148.0 (C

10H

12O

+), due to the cleavage of the bond with α-carbon and amide bond, respectively.

In order to confirm the structure of the novel piperazine derivative (2), precursor ion at

m/z 301.1 was isolated and fragmentated by CID with a collision energy of 7.4 eV, thus obtaining a base peak at

m/z 101.0 corresponding to protonated methyl piperazine (C

5H

13N

2+). A signal at

m/z 173.0 (C

13H

17+), obtained from the loss of a C

6H

12N

2O unit by intramolecular elimination and formation of a new π bond in the detected product ion, was observed. Furthermore, a neutral loss of a C

2H

5N unit through the opening of the cyclic structure of

N-methylpiperazine generated a fragment ion at

m/z 258.0 (C

17H

24NO

+). Product ion at

m/z 101.0 was further fragmented by applying a collision energy of 10.5 eV. Three major fragments were obtained at

m/z 84.0 (C

5H

10N

+), due to the loss of NH

3 following the opening of the piperazine ring,

m/z 70.0 (C

4H

8N

+), due to the loss of a CH

5N unit and

m/z 58.0 (C

3H

8N

+) obtained from the loss of a C

2H

5N unit (

Figure S1). The acquisition in the ion trap of the MS

3 spectra of the precursor ion at

m/z 173.0 with a collision energy of 7.7 eV gave five product ions, namely ion at

m/z 117.0 (C

9H

9+),

m/z 105.0 (C

8H

9+),

m/z 95.0 (C

7H

11+),

m/z 91.0 (C

7H

7+) and

m/z 81.0 (C

6H

9+), whose proposed structures are reported in

Figure S1. Precursor ion at

m/z 258.0 was isolated and further fragmented with a collision energy of 8.7 eV. The obtained MS

3 spectra showed the presence of a signal at

m/z 176.0 (C

11H

14NO

+), which was assigned to fragment obtained by the loss of a C

6H

10 unit following the cleavage of the bond between the cyclohexyl ring and the carbon skeleton.

Table 1. Accurate mass values, relative intensity and mass accuracy, expressed as RMS errors in ppm, of the protonated adducts and isotopologues of new synthetized piperazine ((1) and (2)) derivatives.

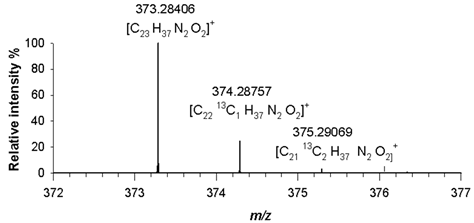

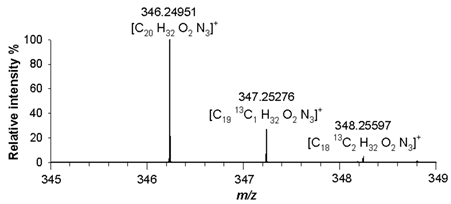

2.2. Mass Spectrometric characterization of Morpholine derivatives

For morpholine derivatives (3), (4), (5) and (6), the FT ICR MS spectra were acquired in positive ion mode (ESI +) due to their reduced p

Ka value [

14]. For compound (3), a dominant molecular ion signal at

m/z 373.28406 ([M+H]

+, C

25H

37N

2O

2+) with only 2.4 ppm difference from the theoretical value, was observed. The observed isotopic pattern of [C

25H

37N

2O

2]

+ was in good agreement with the predicted one, as the signals at

m/z 374.28757 and

m/z 375.29069, related to A+1 and A+2 isotopologues, i.e. [C

2413CH

37N

2O

2]

+ and [C

2313C

2H

37N

2O

2]

+, had mass errors in RMS not exceeding 2.6 ppm (

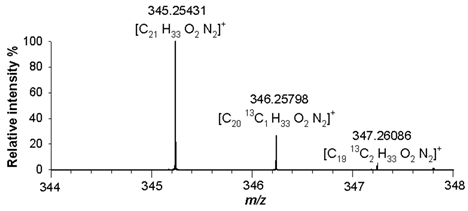

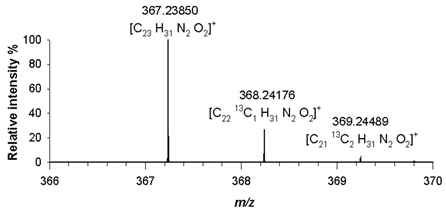

Table 2). A detailed analysis of isotopologue pattern was needed to confirm the elemental composition of (4), (5) and (6) derivatives, whose molecular ion signals were observed in the FT ICR MS spectra at

m/z 345.25431 ([M+H]

+, C

21H

33N

2O

2+, RMS error 1.9 ppm),

m/z 367.23850 ([M+H]

+, C

23H

31N

2O

2+, RMS error 1.4 ppm) and

m/z 346.25091([M+H]

+, C

20H

32N

3O

2+, RMS error 1.8 ppm), respectively. The agreement between the experimental and theoretical values relating to isotopologues A+1 at

m/z 346.25798 ([C

2013CH

33N

2O

2]

+),

m/z 368.24176 ([C

2213CH

31N

2O

2]

+) and

m/z 347.25276 ([C

1913C H

32N

3O

2]

+), and A+2 at

m/z 347.26086 ([C

1913C

2H

33N

2O

2]

+),

m/z 369.24489 ([C

2113C

2H

31N

2O

2]

+) and

m/z 348.25597 ([C

1813C

2H

32N

3O

2]

+), was found with mass errors not exceeding 2.8 ppm (

Table 2).

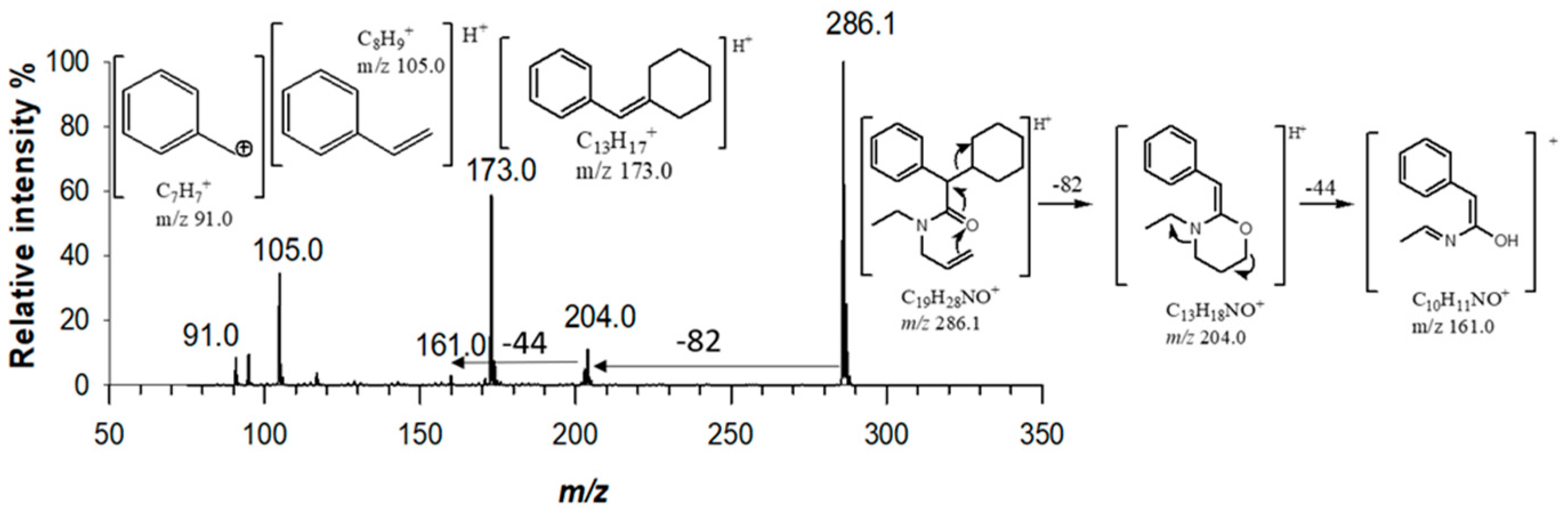

For MS

n operation, tandem mass spectra were generated by optimizing collision energies according to the precursor ion (

Table S1). For derivatives (3) and (4), MS/MS mass spectra exhibited a single fragment ion due to the loss of the morpholine unit (−87.0 Da, C

4H

9NO) [

15], at

m/z 286.1 and

m/z 258.0, respectively. By fragmenting precursor ion at

m/z 286.1 with a collision energy of 8.8 eV, five major fragments were generated at

m/z 204.0 (C

13H

18NO

+),

m/z 173.0 (C

13H

17+)

, m/z 161.0 (C

10H

11NO

+)

, m/z 105.0 (C

8H

9+)

, and

m/z 91.0 (C

7H

7+) (

Figure 3). A cyclic rearrangement following the loss of cyclohexyl moiety has been proposed to explain the presence of fragment ion at

m/z 204.0. Such a fragment ion was not detected in the MS

3 spectra of compound (4), obtained by fragmenting precursor at

m/z 258.0. For this derivative, the loss of 153 Da and 85 Da allowed to confirm the

N-ethyl substituent (

Table S1). The substitution of the cyclohexyl unit with a benzene ring let (5) derivative to fragment according to a different scheme (

Table S1), as a base peak at

m/z 167.0 (C

13H

11+) was observed in the MS/MS spectra, corresponding to a stable diphenylmethane cation [

16], further fragmented by CID-MS

3 experiments. In this case, the loss of the morpholine core gave a signal at

m/z 280.0 (C

19H

22NO

+) with a relative intensity of around 5% compared to base peak. Also, for derivative (6), signal at

m/z 259.0 (C

16H

23N

2O

+), due to the loss of morpholine, had a relative intensity of 5%, while base peak being signal at

m/z 171.0. Such a signal was assigned to fragment ion obtained by amide bond cleavage and was further fragmented with a collision energy of 10.5 eV in order to confirm its identity (

Table S1).

2.3. Antimicrobial activity evaluation

The results obtained in terms of the diameter of the inhibition zone (expressed in mm) and MIC are reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Morpholine derivative

(3) (

Table 3) exhibited a broad spectrum of action, showing a high inhibitory action against 82.83% of the bacterial strains tested, with an inhibition zone between 16 and 31 mm, except for

Micrococcus flavus against which it showed medium inhibitory activity. Particularly,

Enterococcus hirae, Enterococcus faecium,

Enterococcus durans and

Enterococcus gallinarum species were inhibited at a low concentration (3.125 mg/mL) after treatment with compound

(3); the 44.81% of the bacterial strains was inhibited at a concentration of 6.25 mg/ml;

Escherichia coli,

Listeria innocua,

Planococcus psychrotoleratus and

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens showed sensitivity to this compound at a concentration of 12.5 mg/ml, while the remaining strains (

Listeria monocytogenes and

Micrococcus flavus) required a higher inhibition concentration.

The morpholine derivatives

(4) and

(6) (

Table 3) showed a middle-high inhibitory action against all bacterial strains tested, except for the Brochothrix thermosphacta strain which proved a low sensitivity to compound

(4).

A high inhibitory activity of derivative

(4) was observed against 79.3% of the bacterial strains tested, with an inhibition zone between 17 and 26 mm, while a middle inhibitory activity against

Pseudomonas fragi,

Hafnia alvei,

Enterococcus faecalis,

Listeria innocua and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. The 38% of the inhibited strains required a concentration of 12.5 mg/ml, while 34.4% a concentration of 6.25 mg/ml. Only

Enterococcus faecium and

Enterococcus gallinarum species were inhibited at a low concentration of 3.125 mg/ml of this compound (

Table 3).

The derivative

(6) showed a high inhibitory activity against 89.61% of the bacterial strains tested, while a middle action was observed against

Hafnia alvei,

Pseudomonas proteamaculans and

Enterococcus gallinarum. The 48% of strains tested was sensitive at a concentration of 12.5 mg/ml, whereas three

Enterococcus species,

Micrococcus flavus,

Bacillus anthracis and

Pseudomonas orientalis showed sensitivity to compound

(6) at a concentration of 6.25 mg/ml (

Table 3).

The fourth morpholine derivative tested (compound

(5)) was active against the 34.40% of the bacterial strains with a high inhibitory activity observed towards the 20.7% of strains (inhibition zone between 21 and 29 mm). The most of sensitive strains required a low concentration of 3.125 mg/ml (

Table 3).

Moreover, the antimicrobial activity of two piperazine derivatives was evaluated. The derivative

(2) showed a broad action spectrum, with a high inhibitory activity against all bacterial strains tested. In particular, the 44.83% of strains showed sensitivity to this compound at a concentration of 12.5 mg/ml, the 48.27% of strains was inhibited at a concentration of 6.25 mg/ml, while the remaining strains (

Enterococcus casselliflavus and

Bacillus subtilis) required a lower inhibition concentration (

Table 4).

The other piperazine derivative

(1) exhibited an inhibitory activity only against some environment-borne strains;

Bacillus subtilis,

Bacillus anthracis,

Pseudomonas orientalis and

Bacillus cereus strains demonstrated a low sensitivity to the compound at a concentration of 25 mg/ml, while

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain required a lower inhibition concentration of 12.5 mg/ml (

Table 4).

3. Discussion

In the search for effective antimicrobial agents, the literature provides information on a number of heterocyclic compounds, including piperazine derivatives, that showed a broad spectrum of pharmacological effects, including antimicrobial activity. Medicinal chemists have had great success in modifying the basic chemical structures of known antibiotics, both natural and synthetic, where the heterocyclic nucleus forms part of the pharmacophore necessary for specific pharmacological activity. Piperazine is a medically important heterocyclic nucleus consisting of a six-membered ring containing two nitrogen atoms in opposite positions in the ring and it’s frequently found in biologically active compounds in many different therapeutic areas [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

In this work, results showed that compounds demonstrated antimicrobial activity against many tested bacterial species, providing a different inhibitory effect probably linked to different chemical structure. Some of the tested bacteria are foodborne, the most of them comes from meat/naturally fermented meat products and others from milk/milk products; of these, some strains are food spoilage bacteria and other strains are selected autochthonous starter cultures. The rest of the tested bacterial strains come from an environmental matrix; some are destructive, while others are beneficial and responsible of different processes.

The results observed in this study underline the importance and the fundamental role of the derivatives structure in their biological activity. As already known in the literature, compounds containing the morpholine ring have a wide spectrum of biological activity, including the inhibition of microbial protein synthesis [

26,

27,

28]. The compound (4) has the morpholine ring, two heterocyclic rings, a three-membered alkyl chain (n=3) and a retro-amide (NH

2CO) which enhance biological activity [

29,

30]. Compound (5) showed a minor but selective antimicrobial activity, despite having a five-membered alkyl chain (n=5), as the literature reports that a greater length of the alkyl chain corresponds to greater antibacterial activity. Birnie et al. [

31] reported that the presence of long alkyl chains promotes the biological activity of derivatives by increasing lipophilicity and the ability of the compounds to destroy the cell wall of microorganisms. Compounds (4) and (6), with antibacterial activity against all bacterial strains tested, have a three-membered alkyl chain (n=3); the antibacterial action of the compound (4) is enhanced by the presence of the amide group (CONH

2) [

32], while the activity of the compound (6) is enhanced by the presence of urea [

19,

31]. Some studies have shown that the heterocyclic ring is the target of many reactions, leading to the obtaining of biologically active compounds with antimicrobial effects due to the modifications of chemical structure [

33,

34].

For structural characterization of piperazine and morpholine derivatives, High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry with electrospray ionization in positive ion mode (ESI +) using a Fourier Transform Cyclotron Ion Resonance (FT ICR) analyser has been employed. FT-ICR MS is capable of achieving low ppm mass accuracy and high resolving power as the detection signal in the analyzer cell typically lasts for several seconds, resulting in numerous cycles of cyclotron motion [

35]. Therefore, a significant limitation in the number of empirical formulas that can be associated with a m/z could be reached [

36,

37,

38]. As with FT-ICR MS just MS/MS experiments can be conducted, in this work a comprehensive structural characterization of all newly synthesized drugs has been supported by MS

n analysis performed with a positive-mode electrospray ionization mass spectrometer with a quadrupole linear ion trap analyzer (ESI-(+)-LTQ-MS/MS).

Mass spectrometric techniques play a crucial role in the structural characterization of newly synthesized compounds, as they allow to confirm the success of the synthesis by accurate mass measurements, isotopic distribution evaluation, and tandem mass spectrometric data (MS

n). The overall structure of the potential drugs, including atoms arrangements, can be elucidated by MS

n experiments. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) is a well-established and widely accepted analytical technique for novel drugs characterization, due to higher resolving power and higher mass accuracy, and to the possibility to isolate and observe ions for extended periods [

39]. Using HRMS can help meet regulatory requirements, ensuring compound’s safety and efficacy, thus significantly enhances drug development process and helping bring safer and more effective pharmaceuticals to the market.

In conclusion, six new derivatives with a piperazine and morpholine core unit, respectively, have been synthetized in this work. ESI-LTQ-MS in combination with ESI-FT-ICR-MS was proved to play a significant role in the structural characterization of novel piperazine and morpholine derivatives and for the study of fragmentation pathways. Accurate mass measurements, isotope distributions and characteristic fragment ions obtained by MSn experiments were consistent with the basic molecular structure. Results of antimicrobial activity assay showed that the different chemical structure of derivatives seems to play an important role in the width of the action spectrum of each compound on bacterial strains, revealing that the new-synthesized derivatives could be promising candidates to be used as antimicrobial agents.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of derivative (1)

For the synthesis of piperazine derivative (1), an equivalent of 2-phenylbutanoyl chloride was dissolved in toluene at 110.6 °C under continuous stirring. Then, an equivalent of Na2CO3 and 3-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)propan-1-amine were added. The reaction mixture was left for 3 hours under continuous stirring. The product was purified by crystallization in acetonitrile.

4.2. Synthesis of derivative (2)

For the synthesis of piperazine derivative (2), an equivalent of 2-cyclohexyl-2-phenylacetyl chloride was dissolved in toluene at 110.6 °C under continuous stirring. Then, an equivalent of Na2CO3 and N-methylpiperazine were added. The reaction mixture was left for 3 hours under continuous stirring. The product was purified by crystallization in acetonitrile.

4.3. Synthesis of derivatives (3), (4), (5) and (6)

For morpholine derivatives, a previous optimized synthesis was used [

40]. Briefly, a suitable carboxylic acid was refluxed with SOCl

2 in benzene for 4 h and then evaporated in vacuo to yield the crude acyl chloride which then reacted with N-(3-aminopropyl)morpholine in benzene in presence of Na

2CO

3 for 4—5 h to give morpholine derivatives.

4.4. Mass spectrometric analysis

For each piperazine and morpholine derivative, a stock solution at a concentration of 1 mg/mL in MeOH was prepared. For a complete solubilization of the compounds, all prepared solutions were sonicated for 15 minutes (T = 25°C) with a Sonorex Super RK 100/H sonicator (Bandelin electronic, Berlin, Germany). Then, stock solutions were diluted to a final concentration of 1 µg/mL, filtered with 0.2 µm PTFE filters (Whatman Puradisc Syringe Filter) and injected directly into the mass spectrometers. High-resolution ESI mass spectra were acquired in positive ion mode with a 7 T solariX XR FT-ICR MS (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). The capillary voltage was set to 3.9 kV, with a nebulizer gas pressure of 1.2 bar and dry gas flow rate of 4 L/min at 200 °C. Mass spectra were acquired in a mass range of 100–2000 m/z using a time-domain ion signal size of 16 mega-words. and an ion accumulation time of 0.1 s. The number of scans was set to 50. Before the analysis, the mass spectrometer was externally calibrated with NaTFA. In order to study the fragmentation pathway of each derivative, MSn experiments were conducted by using a linear trap quadrupole (LTQ) mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). For ESI(+)-MSn spectra acquisition, source voltage was set to 4.5 kV, temperature of the heated capillary was set to 350 °C, the capillary voltage was set to + 45 V, and the tube lens’ voltage was set to − 75 V. The sheath gas (N2) flow rate was 5 arbitrary units (a.u). Collision energies were optimized for each precursor ion. Mass spectrometric data were imported, elaborated, and plotted by SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software, London, UK).

4.5. Antimicrobial activity

2.5.1. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The different derivatives were tested against a panel of bacterial strains shown in

Table 4. A total of twenty-nine strains of the culture collection of the Department of Sciences, University of Basilicata, Potenza, Italy, were employed as screening microorganisms for this study. All strains were maintained as freeze-dried stocks in reconstituted (11% w/v) skim milk, containing 0.1% w/v ascorbic acid and routinely cultivated in optimal growth conditions [

22] (

Table 5). These bacteria were chosen in order to represent the diversity of food-borne (label from 1 to 20) and environment-borne (label from 21 to 29)

Gram-positive and

Gram-negative species.

2.5.2. Agar Well Diffusion Assay and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

Antimicrobial activity was determined by standard agar well diffusion assay as described by Bonomo et al. [

30]. For each strain, a subculture in a specific broth was obtained from the active stock culture by 1% (v/v) inoculum and incubated overnight at the corresponding culture temperature. 200 μl of each subculture was used to inoculate the agar media (to achieve a final concentration of 10

6 CFU/ml) and distributed into Petri plates. 50 μl of each extract was poured into wells (6 mm diameter) bored in the agar plates and then the plates were incubated at optimal growth conditions for each strain. Organic solvent was used as negative control while chloramphenicol antibiotic was used as positive control. The experiment was performed in triplicate and the antimicrobial activity of each extract was expressed in terms of zone of inhibition diameter mean (in mm) produced by the respective extract after 24 h of incubation. An inhibition zone <10 mm indicated a low antimicrobial activity; 10< zone of inhibition <15 mm, a middle antimicrobial activity; a zone of inhibition >15 mm, a high antimicrobial activity.

Then, each compound was screened to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in order to evaluate the antimicrobial effectiveness of each compound against different bacterial strains by the agar well diffusion method [

30]. Each specific medium inoculated with the strain subculture was distributed into Petri plates and different concentrations of compounds, ranging from 1.562 mg/ml to 50 mg/ml, were poured into wells bored in the agar plates and the plates were incubated for 24 h. After incubation, the MIC was calculated as the lowest concentration of the compound inhibiting the growth of bacterial strains. The MIC values were done in triplicate.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Proposed fragmentation scheme and fragment ions observed in the MSn spectra acquired by collision induced dissociation for piperazine derivative (2); Table S1: Main fragmentation schemes proposed for morpholine derivatives following CID-MS2 and MS3 experiments.

Author Contributions

M.A.A: writing—original draft preparation; data curation; investigation; M.G.B.: methodology, writing—review and editing, supervision; G.B.: methodology, visualization, writing—review and editing, supervision; G.S.: data curation, formal analysis; C.G.: data curation, formal analysis; P.I.: data curation, formal analysis, A.D.C.: data curation, formal analysis, investigation; F.G.: investigation, data curation; C.S.: writing—review and editing, visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Graziana Cardone and Barbara Emanuela Scalese for their support in mass spectrometric data elaboration and antimicrobial activity assay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davies, J. Where have all the raises gone? Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 17, 287–290.

- Hutchings, M.; Truman, A.; Wilkinson, B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 72–80. [CrossRef]

- Gaskins, H.R.; Collier, C.T.; Anderson, D.B. Antibiotics as growth promotants: Mode of action. Anim. Biotechnol. 2002, 13, 29–42. [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.F. The resistance tsunami, antimicrobial stewardship, and the golden age of microbiology. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 171, 273–278. [CrossRef]

- Macgowan, A. Antibiotic resistance. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017, 45, 622–628. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.B.; Young, K.; Silver, L.L. What is an “ideal” antibiotic? Discovery challenges and path forward. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 133, 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Gettys, K.E.; Ye, Z.; Dai, M. Recent Advances in Piperazine Synthesis. Synth. 2017, 49, 2589–2604. [CrossRef]

- Al-Neaimy, U.I.S.; Saeed, Z.F.; Shehab, S.M. A Review on Analytical Methods for Piperazine Determination. NTU J. Pure Sci. 2022, 1, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.A. Novel tactics for designing water-soluble molecules in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2014, 9, 1421–1433. [CrossRef]

- Kourounakis, A.P.; Xanthopoulos, D.; Tzara, A. Morpholine as a privileged structure: A review on the medicinal chemistry and pharmacological activity of morpholine containing bioactive molecules. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 709–752. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghorbani, M.; Begum, B.; Zabiulla; Mamatha, V.S.; Khanum, S.A. Piperazine and morpholine: Synthetic preview and pharmaceutical applications. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2015, 7, 281–301.

- Kumar Rupak , Srinivasa R Vulichi, K.S. Emphasizing morpholine and its derivatives (MAID): a typical candidates of pharmaceutical importance. Int. J. Chem. Sci. 2016, 14, 1777–1788.

- Welz, A.; Koba, M.; Kośliński, P.; Siódmiak, J. Rapid targeted method of detecting abused piperazine designer drugs. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kőnig, B.; Sztanó, G.; Holczbauer, T.; Soós, T. Syntheses of 2- and 3-Substituted Morpholine Congeners via Ring Opening of 2-Tosyl-1,2-Oxazetidine. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 6182–6191. [CrossRef]

- Niessen, W.M.A.; Rosing, H.; Beijnen, J.H. Interpretation of MS–MS spectra of small-molecule signal transduction inhibitors using accurate-m/z data and m/z-shifts with stable-isotope-labeled analogues and metabolites. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 464, 116559. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Seo, H.S.; Ki, N.Y.; Park, N.H.; Lee, W.; Do, J.A.; Park, S.; Baek, S.Y.; Moon, B.; Oh, H. Bin; et al. Reliable screening and confirmation of 156 multi-class illegal adulterants in dietary supplements based on extracted common ion chromatograms by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole/time of flight-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1491, 43–56. [CrossRef]

- Paneth, A.; Trotsko, N.; Popiołek, Ł.; Grzegorczyk, A.; Krzanowski, T.; Janowska, S.; Malm, A.; Wujec, M. Synthesis and Antibacterial Evaluation of Mannich Bases Derived from 1,2,4-Triazole. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16. [CrossRef]

- Turan-Zitouni, G.; Kaplancikli, Z.A.; Yildiz, M.T.; Chevallet, P.; Kaya, D. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of 4-phenyl/cyclohexyl-5-(1- phenoxyethyl)-3-[N-(2-thiazolyl)acetamido]thio-4H-1,2,4-triazole derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 40, 607–613. [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.; Noonikara-Poyil, A.; Joshi, S.D.; Patil, S.A.; Patil, S.A.; Bugarin, A. New urea derivatives as potential antimicrobial agents: Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies. Antibiotics 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kosikowska, U.; Wujec, M.; Trotsko, N.; Płonka, W.; Paneth, P.; Paneth, A. Antibacterial activity of fluorobenzoylthiosemicarbazides and their cyclic analogues with 1,2,4-triazole scaffold. Molecules 2021, 26, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Wujec, M.; Kosikowska, U.; Siwek, A.; Malm, A. New Derivatives of Thiosemicarbazide and 1,2,4-Triazoline-5-thione with Potential Antimicrobial Activity. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2009, 184, 559–567. [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, M.G.; Cafaro, C.; Russo, D.; Calabrone, L.; Milella, L.; Saturnino, C.; Capasso, A.; Salzano, G. Antimicrobial Activity, Antioxidant Properties and Phytochemical Screening of Aesculus hippocastanum Mother Tincture against Food-borne Bacteria. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2018, 17, 48–56. [CrossRef]

- Siwek, A.; Wujec, M.; Dobosz, M.; Jagiełło-Wójtowicz, E.; Chodkowska, A.; Kleinrok, A.; Paneth, P. Synthesis and pharmacological properties of 3-(2-methyl-furan-3-yl)-4-substituted-Δ 2 - 1,2,4-triazoline-5-thiones. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2008, 6, 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Kharb, R.; Bansal, K.; Sharma, A.K. A valuable insight into recent advances on antimicrobial activity of piperazine derivatives. Der Pharma Chem. 2012, 4, 2470–2488.

- Lukin, A.; Chudinov, M.; Vedekhina, T.; Rogacheva, E.; Kraeva, L.; Bakulina, O.; Krasavin, M. Exploration of Spirocyclic Derivatives of Ciprofloxacin as Antibacterial Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, S.M.R.; Farhadi, T.; Ganjparvar, M. Linezolid: A review of its properties, function, and use in critical care. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2018, 12, 1759–1767. [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; Bonomo, M.G.; Vassallo, A.; Palma, G.; Calabrone, L.; Bimonte, S.; Silvestris, N.; Amruthraj, N.J.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Salzano, G.; et al. Linezolid and its derivatives: The promising therapeutic challenge to multidrug-resistant pathogens. Pharmacologyonline 2018, 2, 134–148.

- Bonomo, M.G.; Calabrone, L.; Saturnino, C.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Capasso, A.; Salzano, G. Antibacterial activity of new β-lactam compound. Pharmacologyonline 2019, 3, 185–194.

- Lee, S.K.; Choi, K.H.; Lee, S.J.; Suh, S.W.; Kim, B.M.; Lee, B.J. Peptide deformylase inhibitors with retro-amide scaffold: Synthesis and structure-activity relationships. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4317–4319. [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, M.G.; Giura, T.; Salzano, G.; Longo, P.; Mariconda, A.; Catalano, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Saturnino, C. Bis-Thiourea Quaternary Ammonium Salts as Potential Agents against Bacterial Strains from Food and Environmental Matrices. Antibiotics 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Birnie, C.R.; Malamud, D.; Schnaare, R.L. Antimicrobial evaluation of N-Alkyl betaines and N-Alkyl-N,N-dimethylamine oxides with variations in chain length. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2514–2517. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.J.; Rao, X.P.; Shang, S. Bin; Song, Z.Q.; Shen, M.G.; Liu, H. Synthesis, structure analysis and antibacterial activity of N-[5-dehydroabietyl-[1,3,4]thiadiazol-2-yl]-aromatic amide derivatives. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, S258–S263. [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, H.; Demirbas, A.; Karaoglu, S.A.; Demirbas, N. Synthesis of some new 1,2,4-triazoles, their Mannich and Schiff bases and evaluation of their antimicrobial activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 1057–1066. [CrossRef]

- Saturnino, C.; Grande, F.; Aquaro, S.; Caruso, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Bonomo, M.G.; Longo, P.; Schols, D.; Sinicropi, M.S. Chloro-1,4-dimethyl-9H-carbazole derivatives displaying anti-HIV activity. Molecules 2018, 23. [CrossRef]

- Adamson, J.T.; Hakansson, K. Electrospray Ionization Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry for Lectin Analysis. Lectins Anal. Technol. 2007, 343–371. [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, J.S.D.; Monroe, M.E.; Qian, W.J.; Smith, R.D. Advances in proteomics data analysis and display using an accurate mass and time tag approach. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2006, 25, 450–482. [CrossRef]

- Onzo, A.; Acquavia, M.A.; Pascale, R.; Iannece, P.; Gaeta, C.; Nagornov, K.O.; Tsybin, Y.O.; Bianco, G. Metabolic profiling of Peperoni di Senise PGI bell peppers with ultra-high resolution absorption mode Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 470, 116722. [CrossRef]

- Onzo, A.; Acquavia, M.A.; Pascale, R.; Iannece, P.; Gaeta, C.; Lelario, F.; Ciriello, R.; Tesoro, C.; Bianco, G.; Di Capua, A. Untargeted metabolomic analysis by ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry for the profiling of new Italian wine varieties. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 7805–7812. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhu, C.; Xia, H. HRMS studies on the fragmentation pathways of metallapentalyne. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 136, 906–910. [CrossRef]

- Saturnino, C.; Capasso, A.; Lancelot, J.C.; Rault, S.; Buonerba, M.; De Martino, G. Pharmacological studies and synthesis of morpholino alkyl derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 1151–1154. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).