Submitted:

22 December 2023

Posted:

26 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

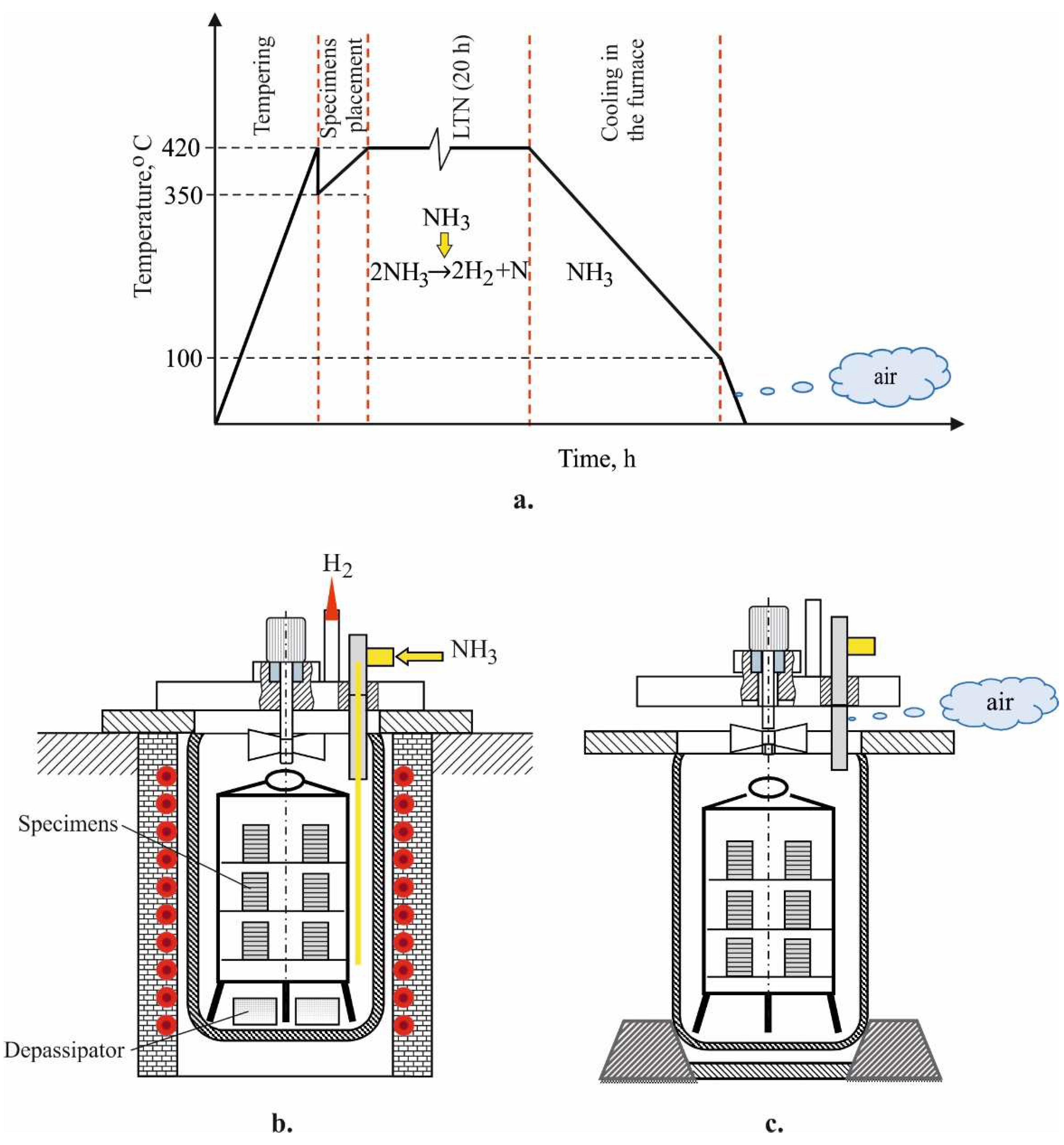

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

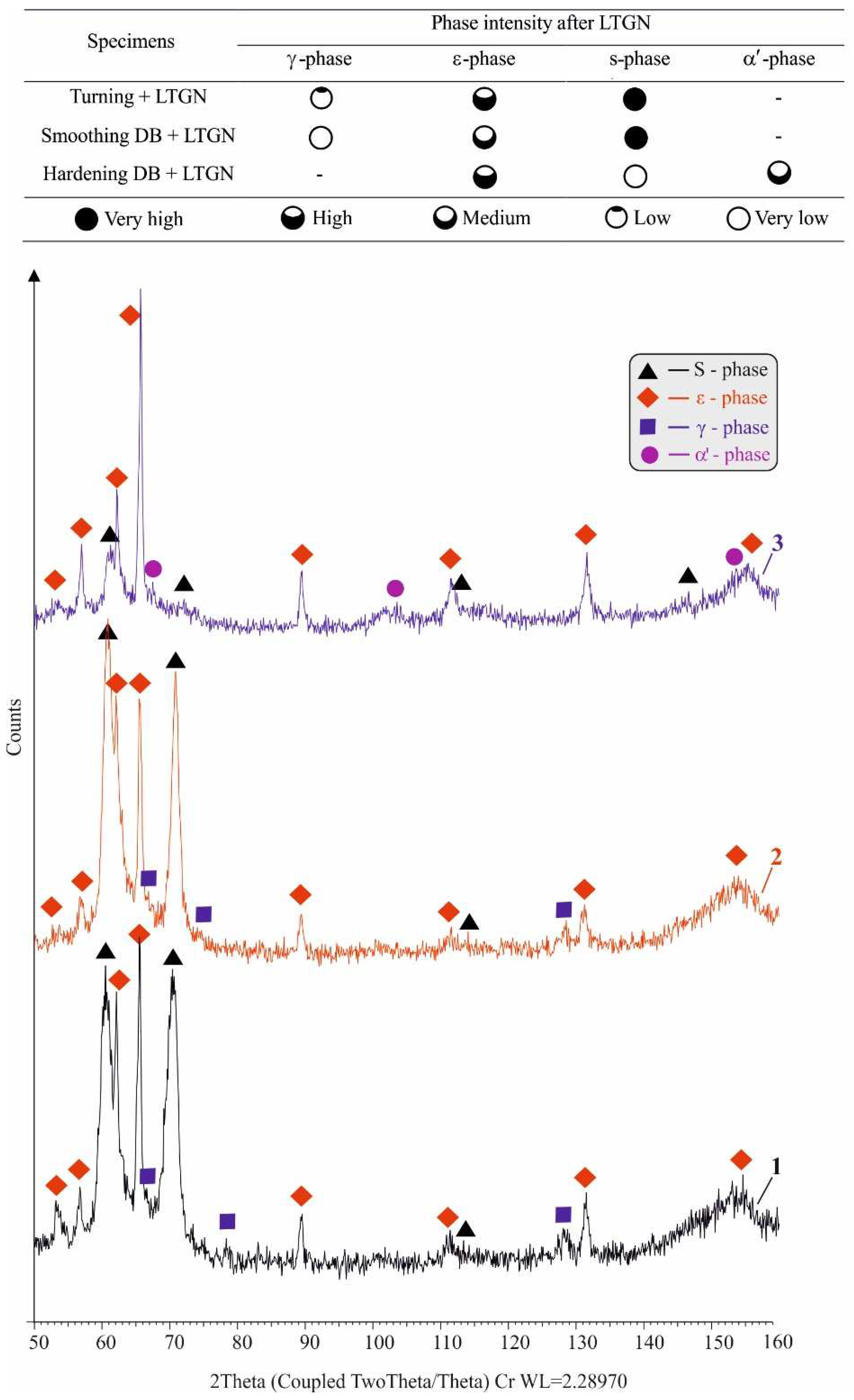

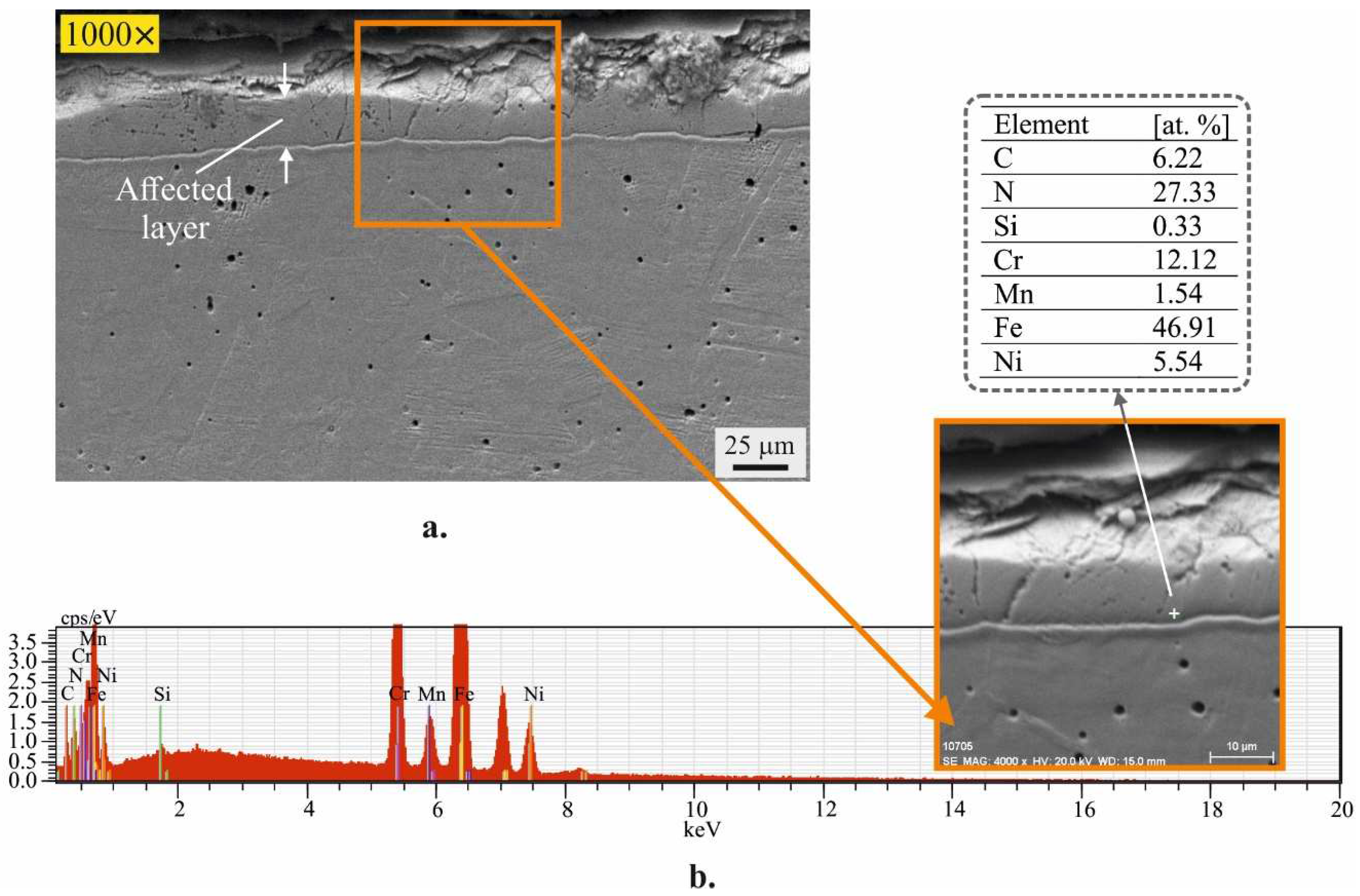

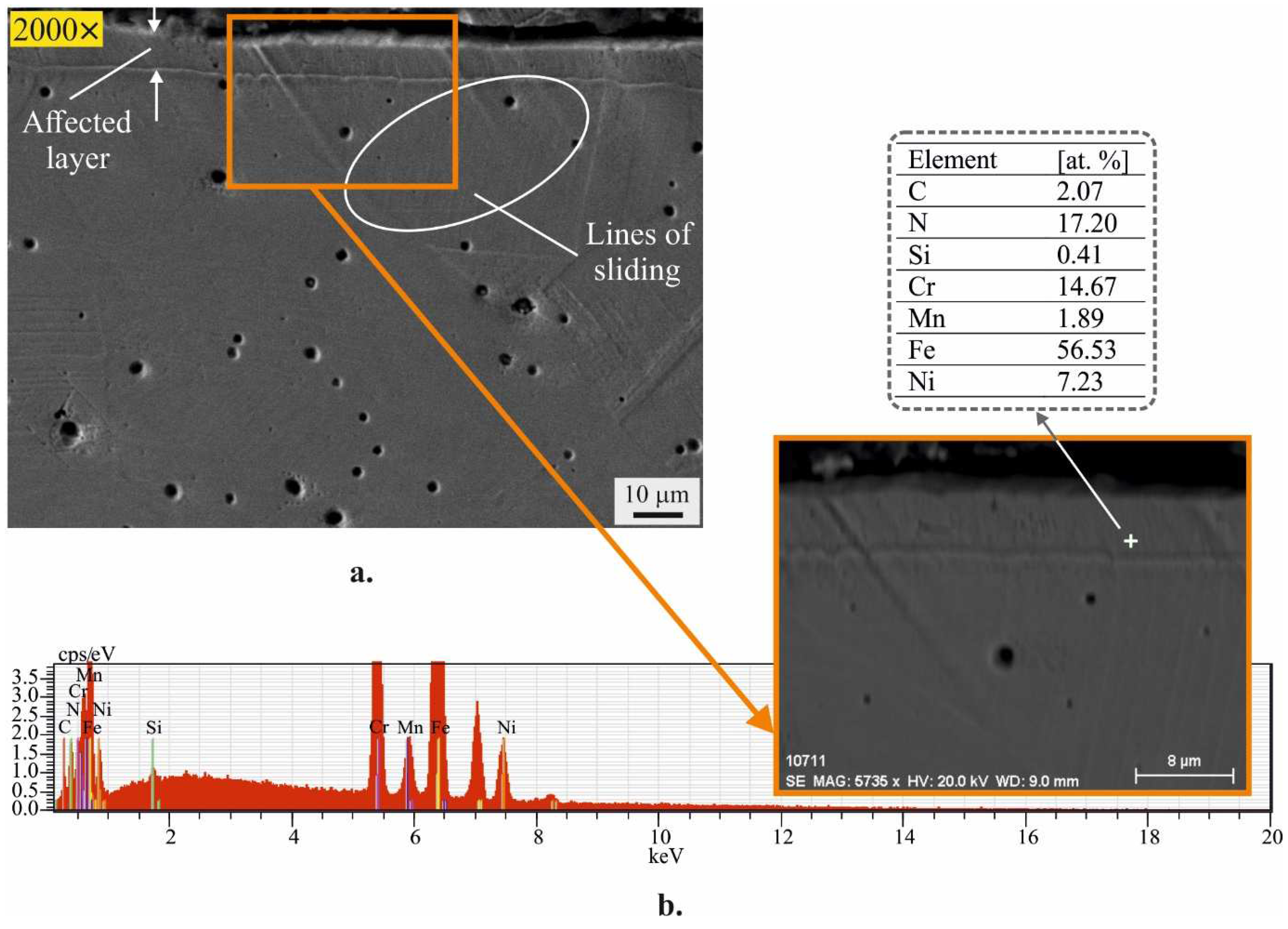

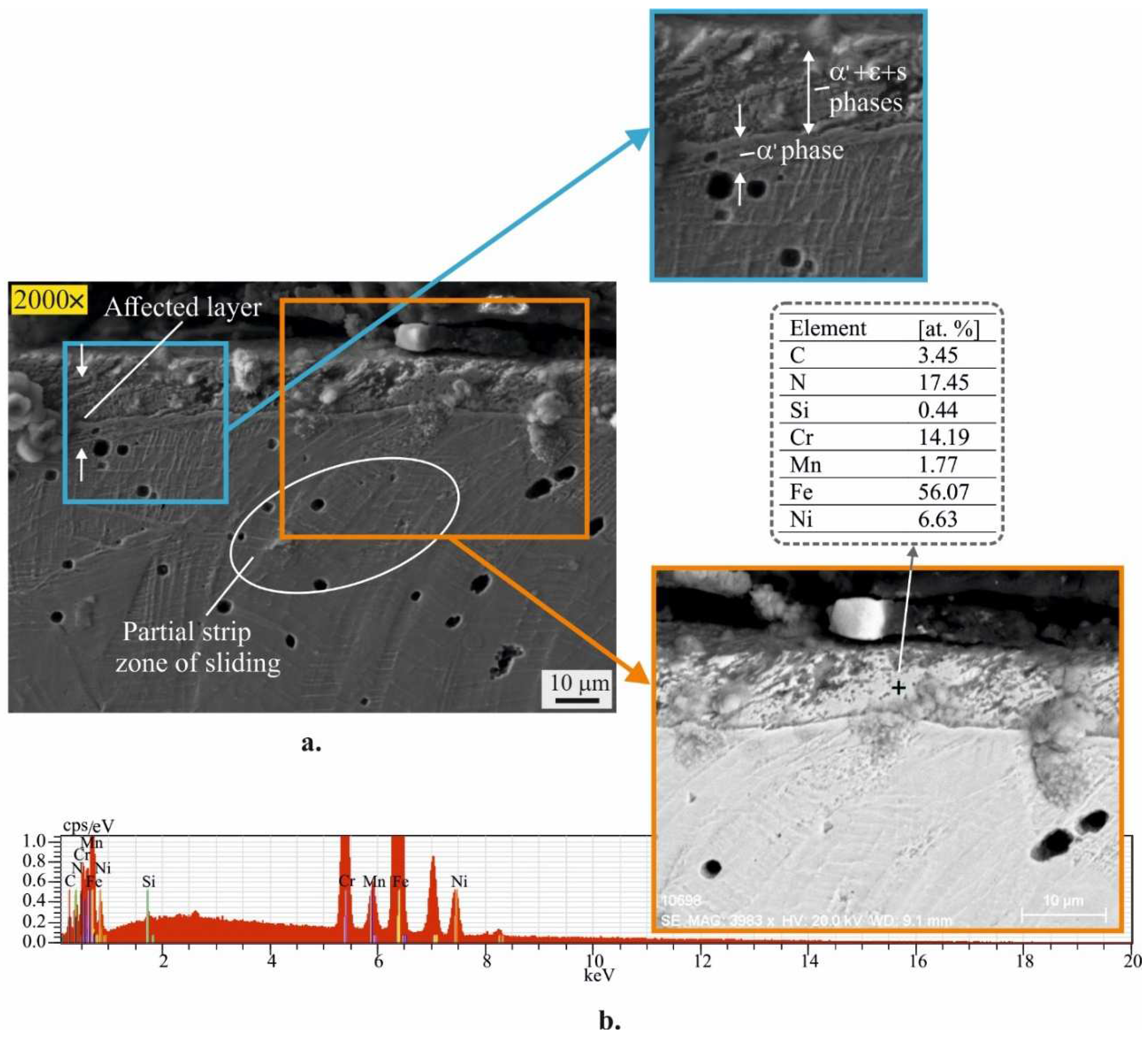

3.1. Effect of DB and LTGN on the Microstructure

- The plastic deformation of the surface layer introduced before LTGN by static cold working with sliding friction contact (i.e., by DB) diminishes the diffusion process aiming at nitrogen enrichment of the surface layer and the closely located subsurface layers, which is confirmed by EDX the analyses. Thus, as the degree of surface plastic deformation increases, the quality of the S-phase formed by LTGN deteriorates. The preliminary impact through severe surface plastic deformation reduces the intensity of the S-phase, but increases the intensity of the ε-phase, and leads to the appearance of a new (also hard) phase: stabilized nitrogen-bearing martensite.

- This conclusion is generally supported by Proust et al. [47] who, for 316L steel, found that the average depth of the nitrogen-rich layer is 24.8 μm (425°C/20 h plasma nitriding), but after preliminary surface mechanical attrition treatment is only 5 μm.

- Ignoring the negligible amount of γ-phase in the first two samples, the ALs of all three samples contain hard phases in different proportions. A significant increase in microhardness and surface residual stresses can be anticipated for each of the three processes: 1) turning andLTGN; 2) smoothing DB and LTGN; and 3) hardening DB and LTGN.

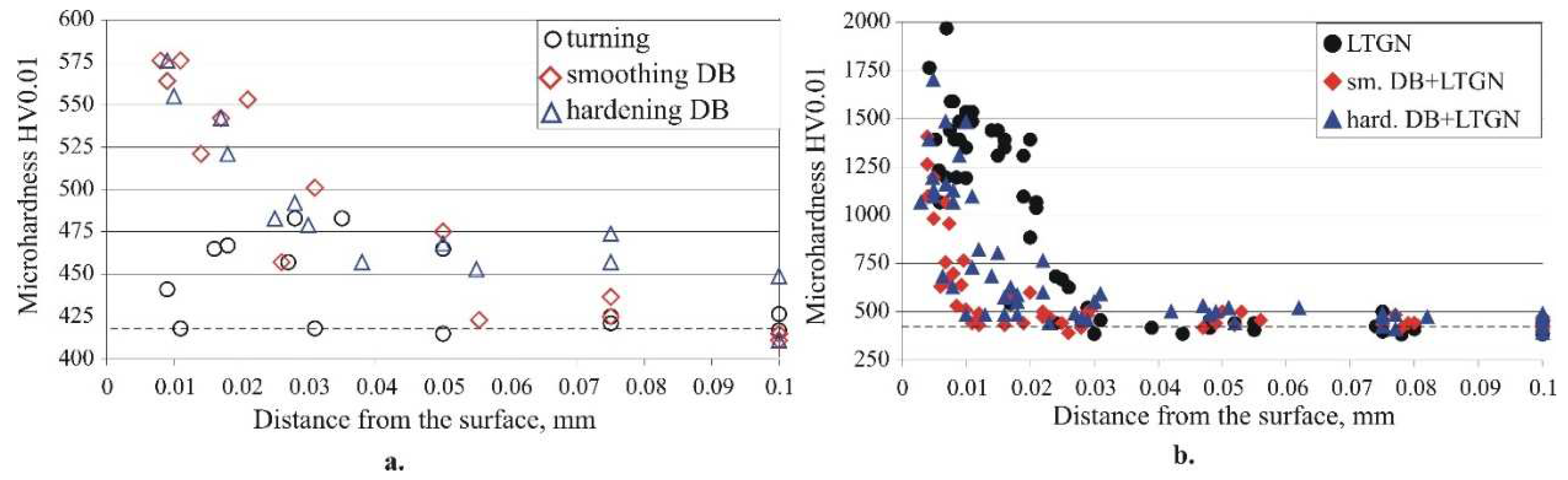

3.2. Effect of DB and LTGN on the SI Physical-Mechanical Characteristics

3.2.1. Microhardness

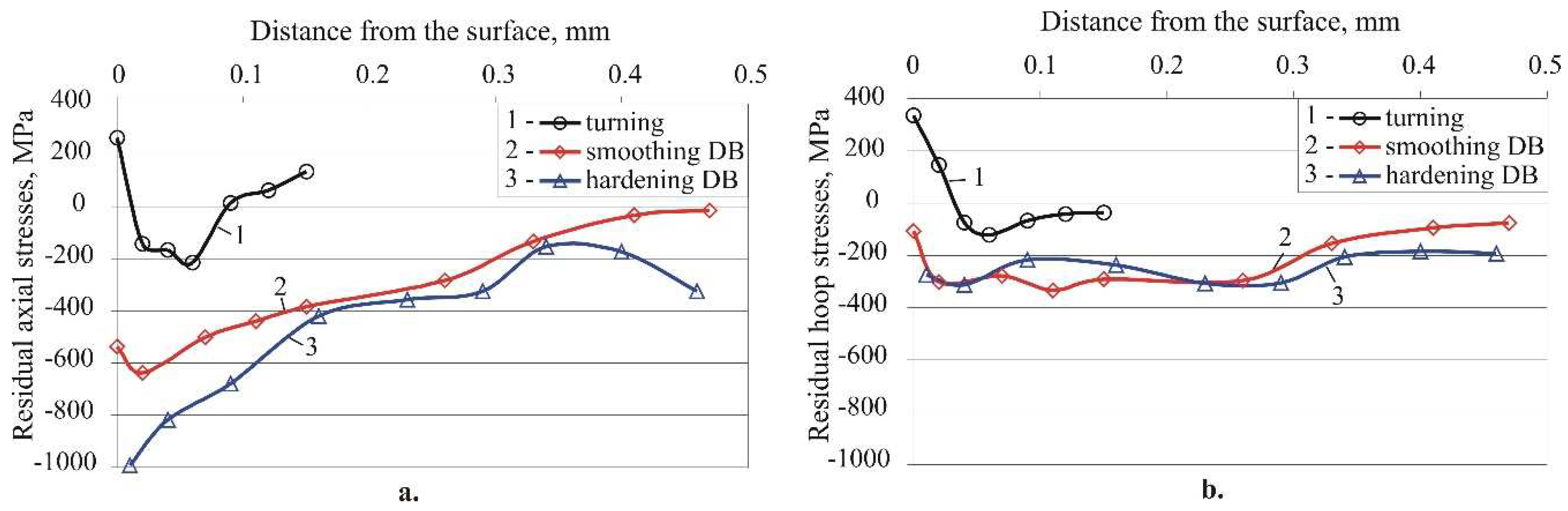

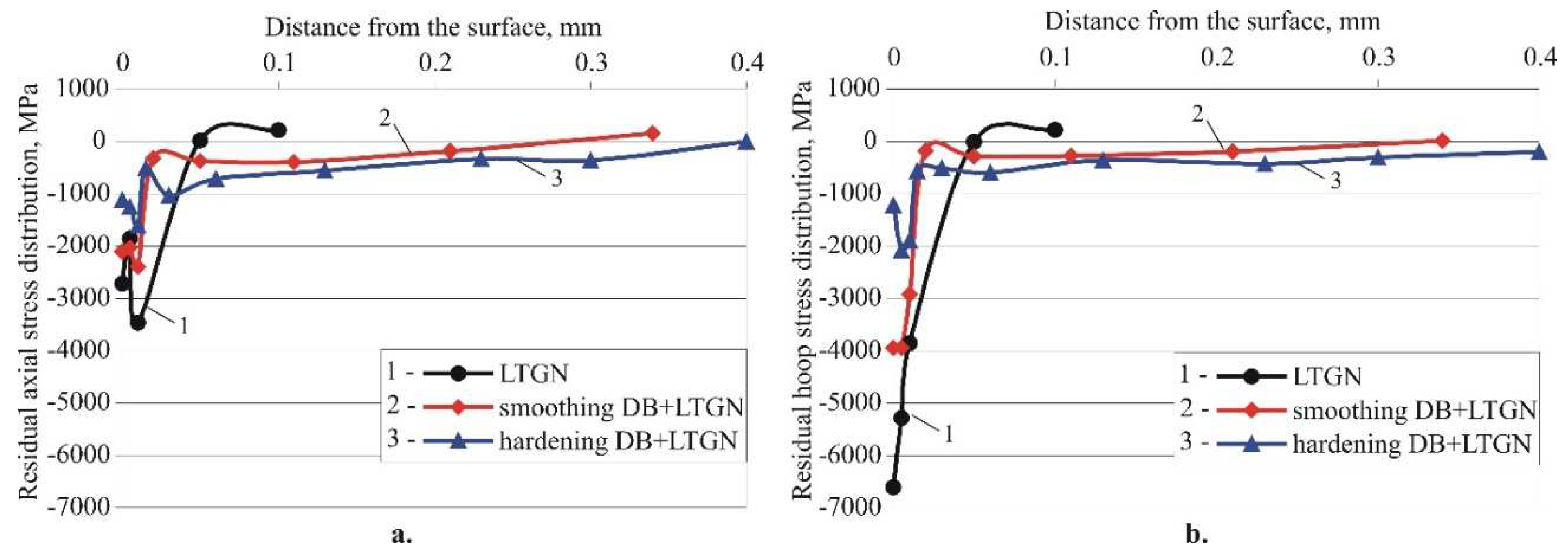

3.2.2. Residual Stresses

3.3. Effect of DB and LTGN on Fatigue Behaviour of 304 CNASS

3.3.1. S-N Curves

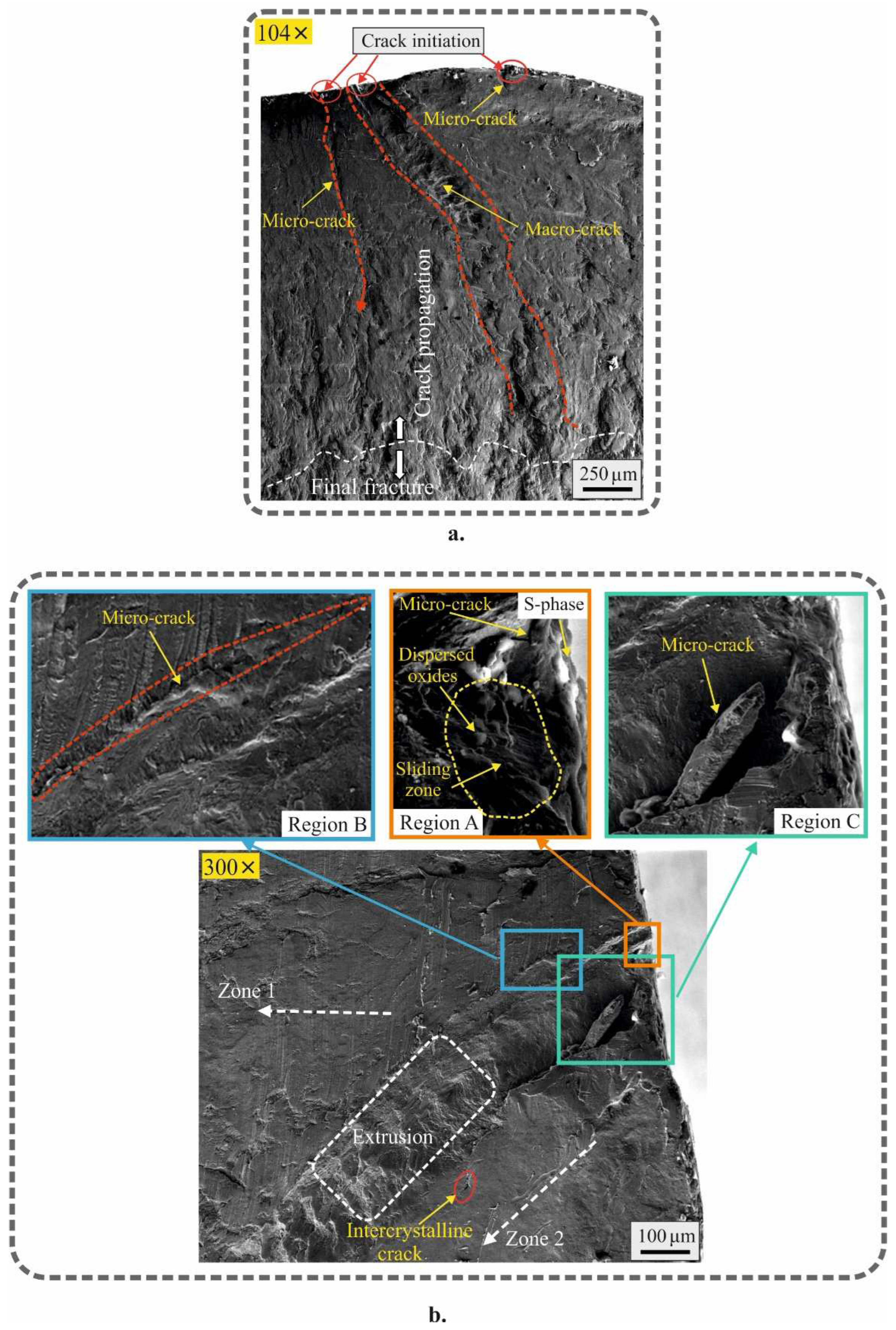

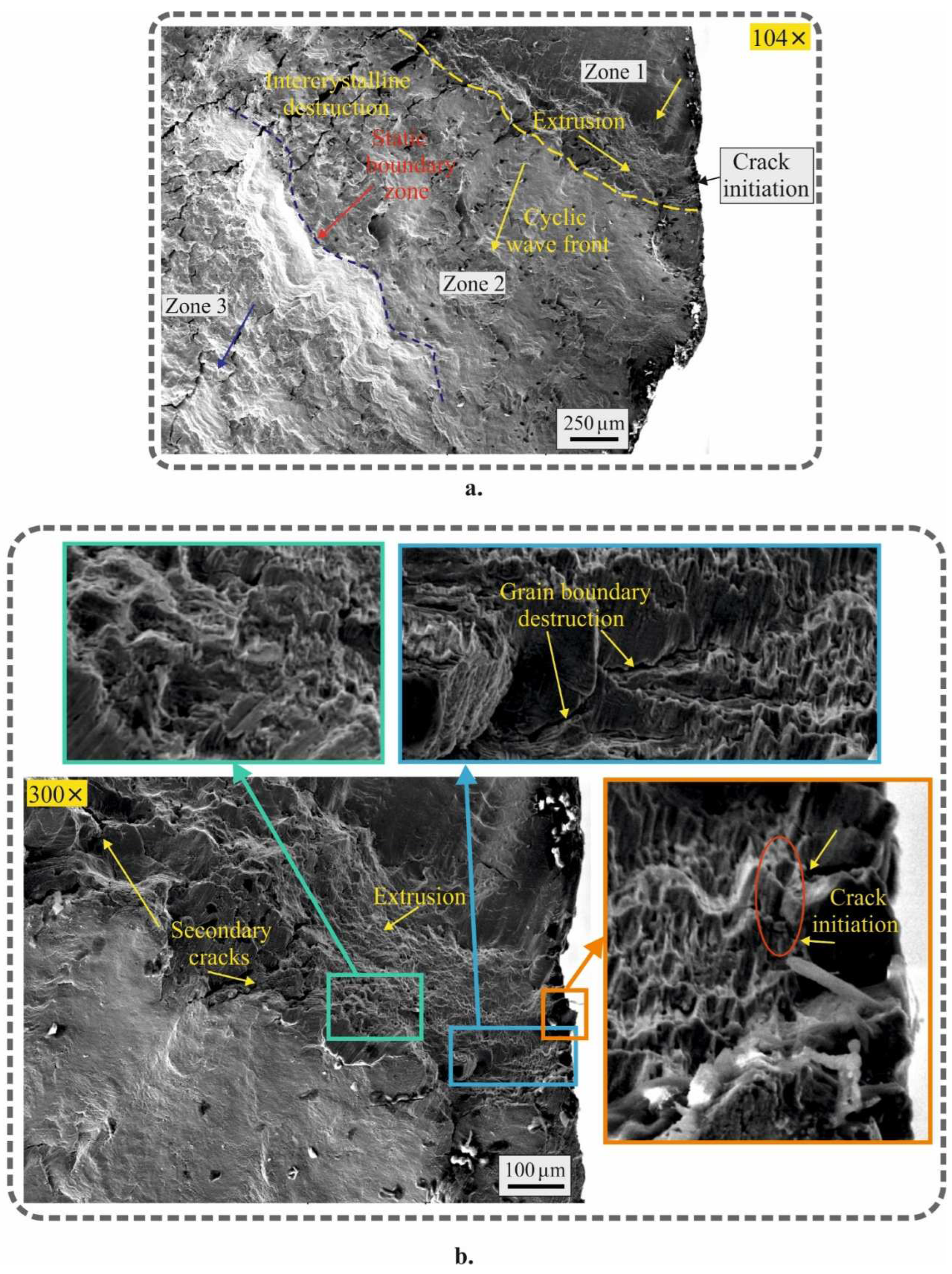

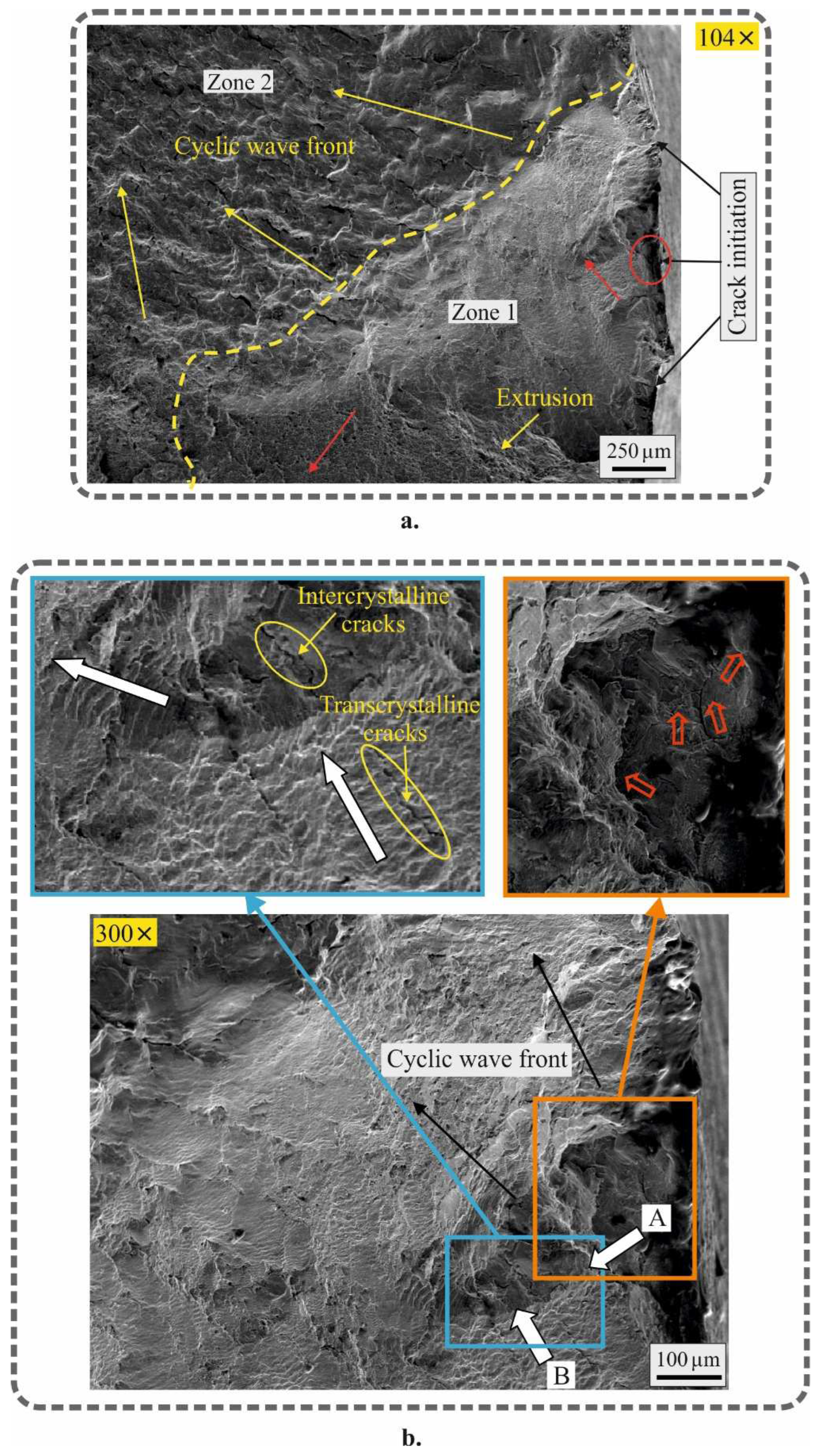

3.3.2. Fractography

4. Conclusions

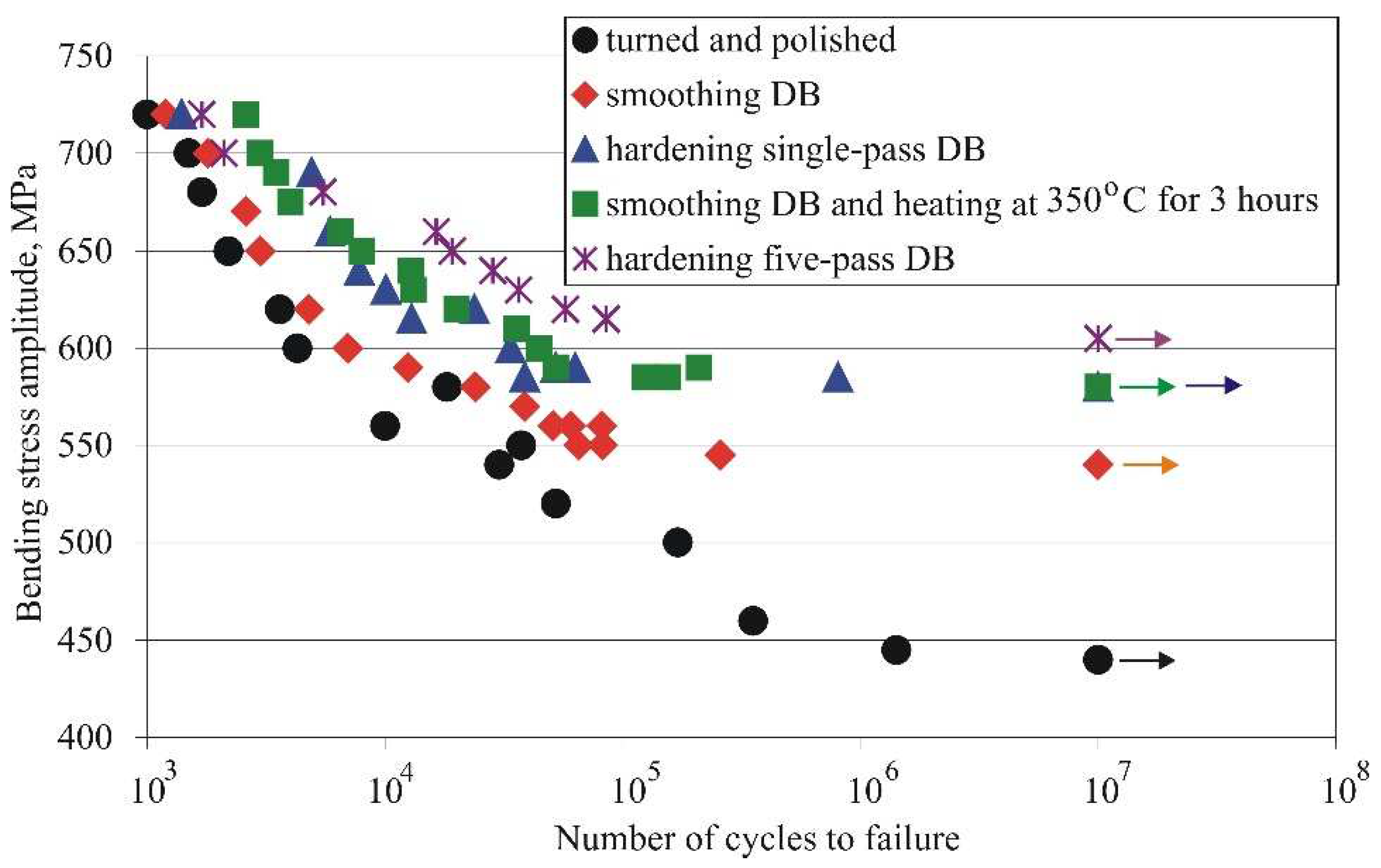

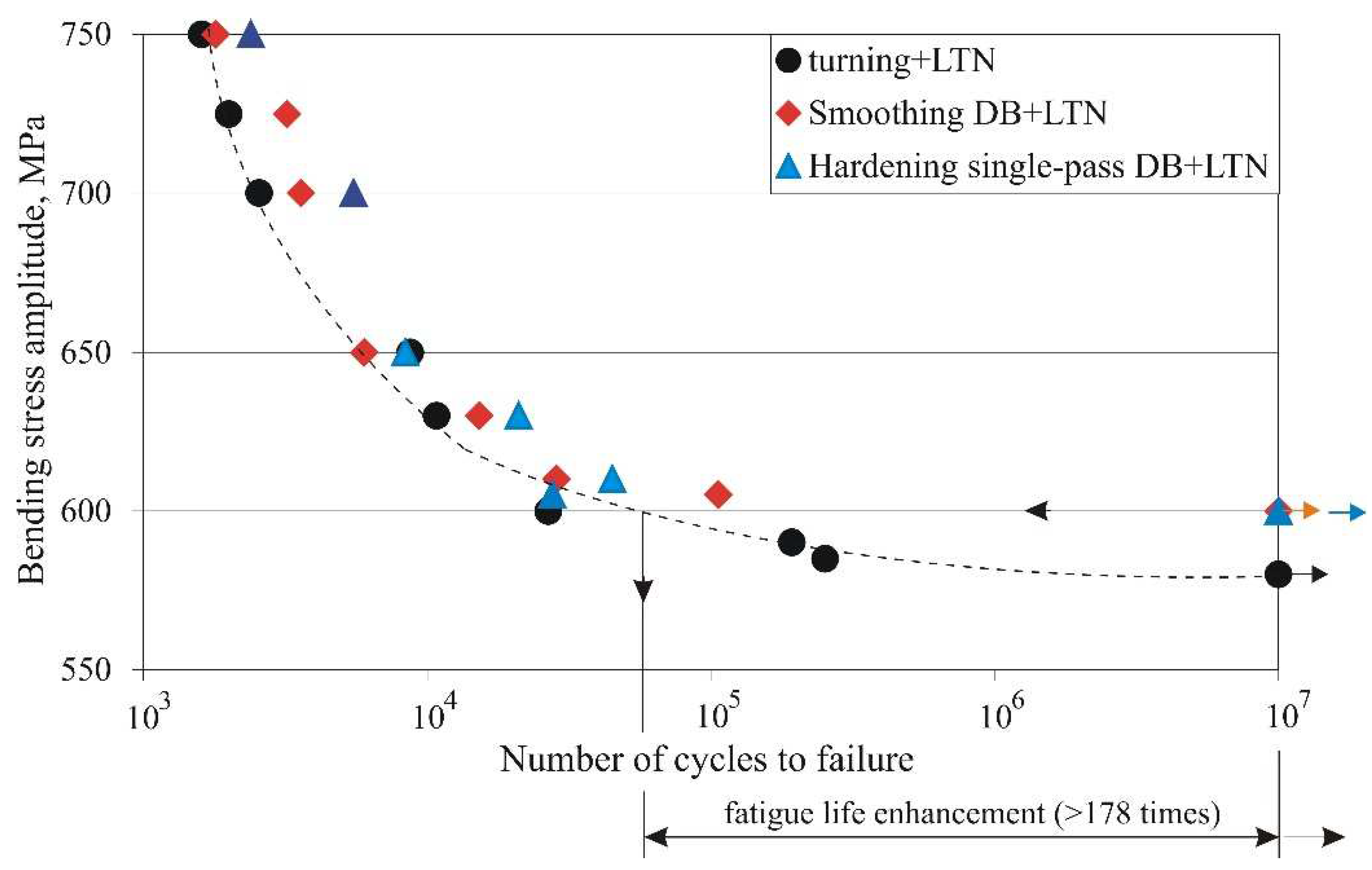

- The approach generates a synergistic effect, as the obtained fatigue limit (600 MPa) is greater than that achieved by DB (540 MPa for smoothing, or 580 MPa for single-pass hardening processes) or LTGN (580 MPa) alone. The synergistic effect is the result of the superimposition of two consecutive effects – strain hardening via DB and transformation hardening via LTGN as a result of the formation of new solid phases with an increased volume of the crystal lattice. It is advisable to use smoothing DB (instead of hardening) in combination with LTGN, as lower roughness height parameters are obtained.

- As the degree of plastic deformation of the surface layer (introduced by DB) increases, the content of the S-phase in the nitrogen-rich layer formed by LTGN decreases, with resultant increased content of the ε-phase, and a new (also hard) phase: stabilized nitrogen-bearing martensite.

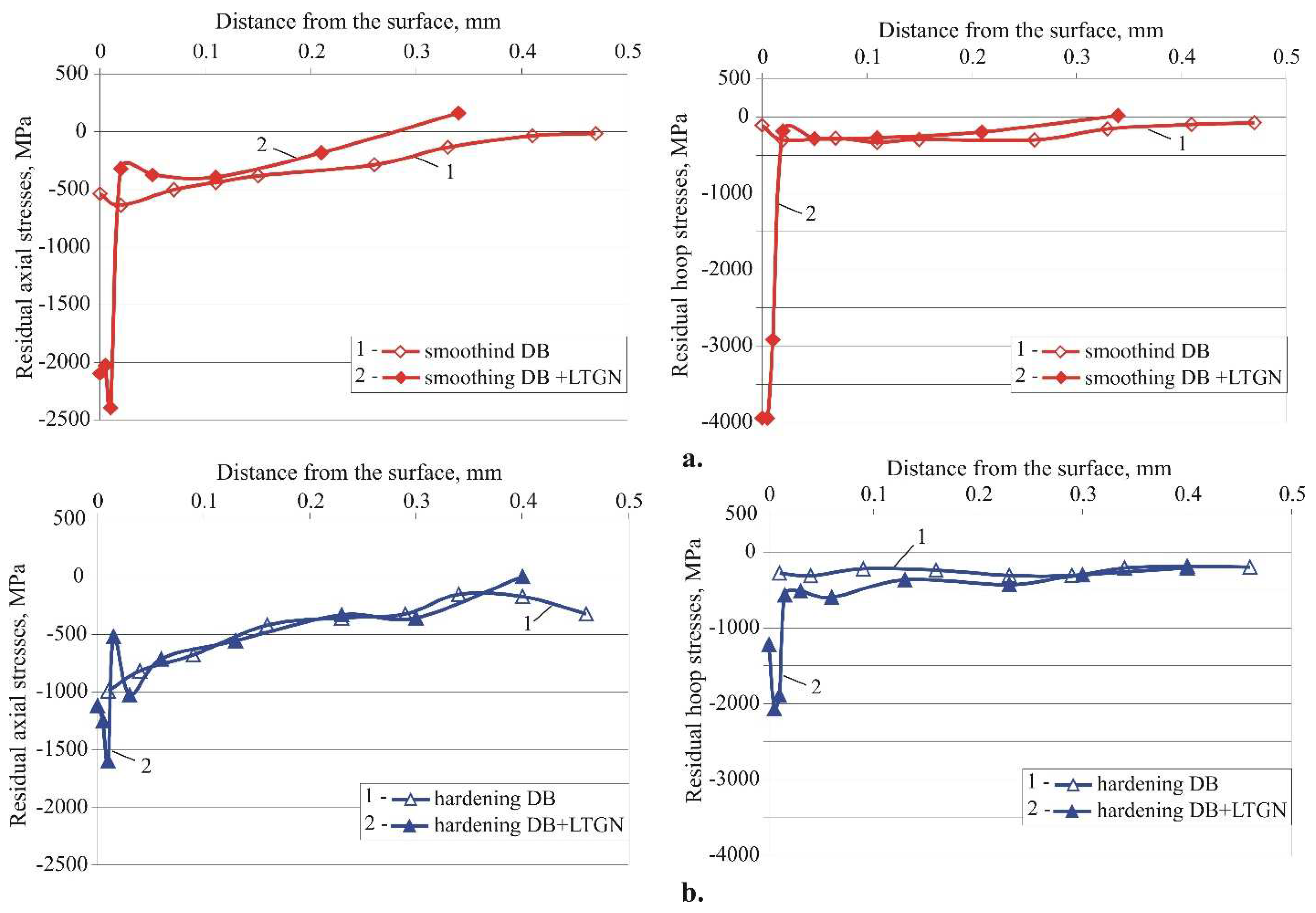

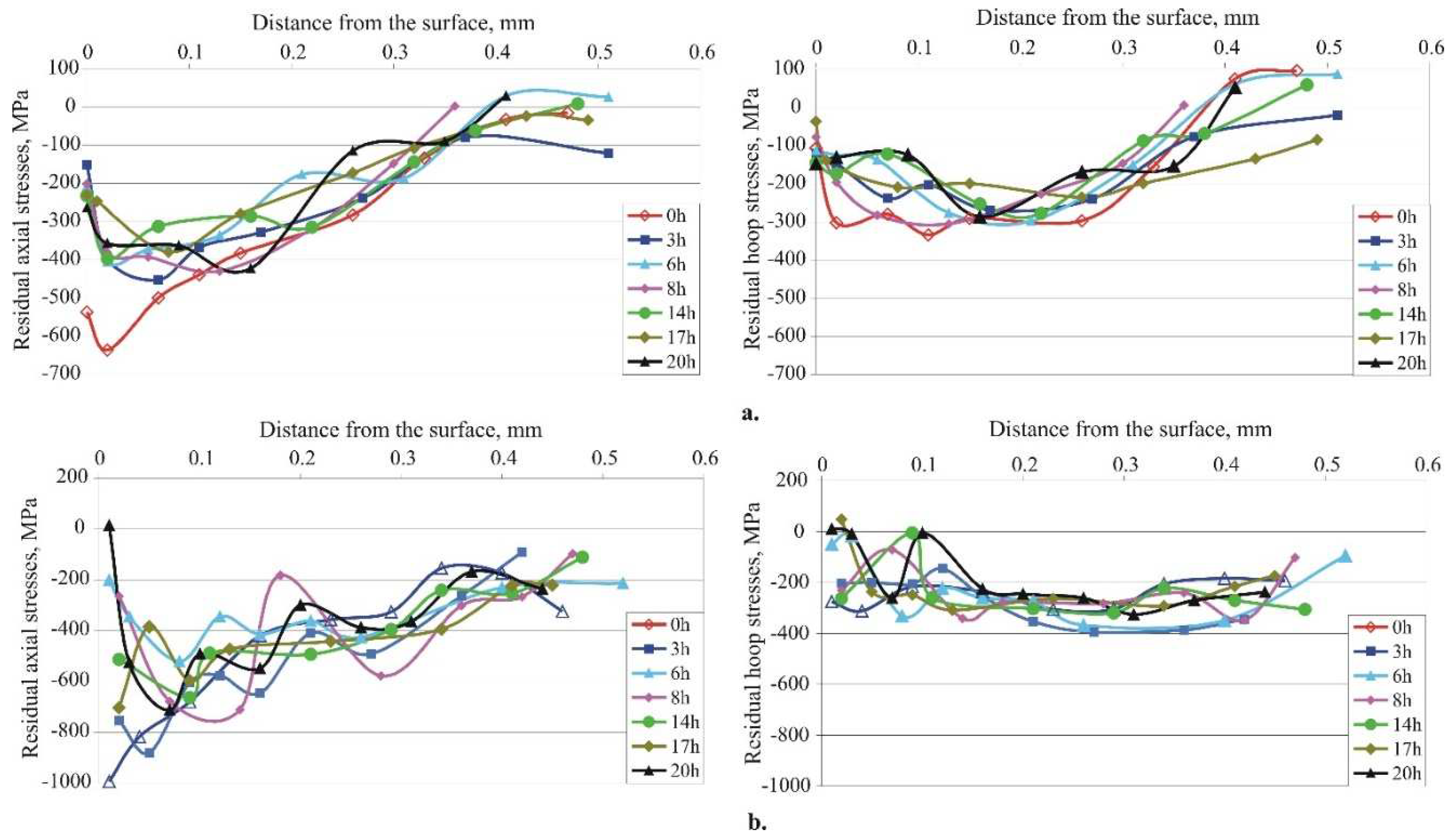

- It was found that axial residual stresses introduced into external cylindrical surfaces by LTGN are 2.43 times smaller compared to the hoop stresses, whose absolute value reaches 6.6 GPa. This trend is opposite to the typical nature of distribution of the two types of residual stresses after the static SCW method.

- The application of a combined process including DB and subsequent LTGN results in many times greater depth of the zone with compressive residual stresses, and significantly surface axial and hoop residual stresses compared to turning and LTGN. At the same time, the hoop surface residual stresses decrease at the expense of the axial ones. These trends are more pronounced with an increase in the degree of preliminary plastic deformation.

- The two combined processes (smoothing DB and LTGN, and single-pass hardening DB and LTGN) were found to achieve the same fatigue limit of 600 MPa, an improvement of 3.45% compared to the turning and LTGN process. However, the two combined processes increase the fatigue life more than 178 times compared to the turning and LTGN process. The main reason for this improvement is the reduced residual stress distribution gradient and deeper compression zone obtained by these processes.

- The formation of a fatigue macrocrack for all three groups of samples (turning+polishing+LTGN, smoothing DB+LTGN and single-pass hardening DB+LTGN) in the high-cycle fatigue field takes place at the boundary between the nitrogen-rich layer and the bulk material, which determines the similar mechanism of destruction of the three samples.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balevski A. Metal Science. Technika, Sofia, 1988.

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V.; Anchev, A.P.; Dunchev, V.P.; Argirov, Y.B. Effect of Diamond Burnishing on Fatigue Behaviour of AISI 304 Chromium-Nickel Austenitic Stainless Steel. Materials 2022, 15, 4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V.; Anchev, A.P.; Dunchev, V.P.; Argirov, Y.B.; Nikolova, M.P. Effects of heat treatment and diamond burnishing on fatigue behaviour and corrosion resistance of AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T. , Duncheva, G.V., Anchev, A.P., Ganev, N., Amudjev, I.M., Dunchev, V.P. Effect of slide burnishing method on the surface integrity of AISI 316Ti chromium-nickel steel. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng 2018, 40, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, E.H.; Nerad, A.J. Irregular diamond burnishing tool. United States patent 2966722, patented Jan, vol 3, p 1961.

- Shi, Y.L.; Shen, X.H.; Xu, G.F.; Xu, C.H.; Wang, B.L.; Su, G.S. Surface integrity enhancement of austenitic stainless steel treated by ultrasonic burnishing with two burnishing tips. Archiv Civ Mech Eng 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D.A.; Martins, A.M.; de Castro, M.F.; Abrao, A.M. Characterization of the topography generated by low plasticity burnishing using advanced techniques. Surf Coat Technol 2022, 448, 128891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juijerm, P.; Altenberger, I. Fatigue performance enhancement of steels using mechanical surface treatments. J Met Mater Miner 2007, 17, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Juijerm, P.; Altenberger, I. Fatigue performance of high-temperature deep-rolled metallic materials. J Met Mater Miner 2007, 17, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Cubillos, J.; Coronado, J.J.; Rodriguez, S.A. Deep rolling effect on fatigue behaviour of austenitic stainless steels. Int J Fatigue 2017, 95, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, I.; Altenberger, I.; Scholtes, B. Effects of deep rolling at elevated and low temperatures on the isothermal fatigue of AlSl304. Alternative Processes 2005, 70, 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin, I.; Altenberger, I. Comparison of the fatigue behaviour and residual stress stability of laser-shock peened and deep rolled austenitic stainless steel AISI 304 in the temperature range 25–600oC. Mater Sci Eng A 2007, 465, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, I.; Scholtes, B.; Maier, H.J.; Altenberger, I. High temperature fatigue behaviour and residual stress stability of laser-shock peened and deep rolled austenitic steel AISI 304. Scripta Materialia 2004, 50, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenberger, I.; Scholtes, B.; Martin, U.; Oettel, H. Cyclic deformation and near surface microstructures of shot peened or deep rolled austenitic stainless steel AISI 304. Mater Sci Eng A 1999, 264, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, I.; Besel, M. Residual stress relaxation of deep-rolled austenitic steel. Scripta Materialia 2008, 58, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, G.; Saelzer, J.; Biermann, D. Finite element analysis of the surface finishing of additively manufactured 316L stainless steel by ball burnishing. Procedia CIRP 2023, 117, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.G.; Tam, S.C.; Loh, N.H. Ball burnishing of 316L stainless steel. J Mater Process Technol 1993, 37, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.; Sadeler, R. Effect of ball burnishing treatment on the fatigue behavior of 316L stainless steel operating under anodic and cathodic polarization potentials. Metall Mater Trans A 2018, 49, 5393–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.; Sadeler, R. Impact wear behaviour of ball burnished 316L stainless steel. Surf Coat Technol 2019, 363, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanakulwattana, W.; Nakkiew, W. Residual stress analysis in deep rolling process on gas tungsten arc weld of stainless steel AISI 316L. Key Eng Mater 2021, 880, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadi, A.J.; Hosseini, S.R.; Naderi, S.M. Formation of surface nano/ultrafine structure using deep rolling process on the AISI 316L stainless steel. MaterSci Eng Int J 2017, I, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkurt, A. Comparison of roller burnishing method with other hole surface finishing processes applied on AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel. J Mater Eng Perform 2011, 20, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Moussa, N.; Gharbi, K.; Chaieb, I.; Ben Fredj, N. Improvement of AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel low-cycle fatigue life by initial and intermittent deep rolling. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2019, 101, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, K.; Ben Moussa, N.; Ben Rhouma, A.; Ben Fredj, N. Improvement of the corrosion behavior of AISI 304L stainless steel by deep rolling treatment under cryogenic cooling. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2021, 117, 3841–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugay, I.O.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Yapici, G.G. Hardness and wear resistance of roller burnished 316L stainless steel. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 47, 2405–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga. G.; Ferencsik, V. Experimental examination of surface micro-hardness improvement ratio in burnishing of external cylindrical workpieces. Cutting & Tools in Technological System 2020, 93, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Felho, C.; Varga, G. 2D FEM investigation of residual stress in diamond burnishing. J Manuf Mater Process, 2022, 6, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, V.; Makarov, A.; Skorobogatov, A.; Skorinina, P.; Luchko, S.; Sirosh, V.; Chekan, N. Influence of normal force on smoothing and hardening of the surface layer of steel 03X16N15M3T1 during dry diamond smoothing with a spherical indenter. Metal Processing 2022, 24, 6–22. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Konefal, K.; Korzynski, M.; Byczkowska, Z.; Korzynska, K. Improved corrosion resistance of stainless steel X6CrNiMoTi17-12-2 by slide diamond burnishing. J Mater Process Technol 2013, 213, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Shinya, M.; Matsubara, H.; Kozuka, H.; Tachiya, H.; Asakawa, N.; Otsu, M. Development and characterization of diamond tip burnishing with a rotary tool. J Mater ProcessTechnol 2017, 244, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Ishii, W.; Yanagi, K. Optimal Burnishing Conditions and Mechanical Properties of Surface Layer by Surface Modification Effect Induced of Applying Burnishing Process to Stainless Steel and Aluminum Alloy. Journal of the Japan Society for Technology of Plasticity 2011, 52, 726–730. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzynski, M.; Dudek, K.; Kruczek, B.; Kocurek, P. Equilibrium surface texture of valve stems and burnishing method to obtain it. Tribology International 2018, 124, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzynski, M.; Dudek, K.; Palczak, A.; Kruczek, B.; Kocurek, P. Experimental models and correlations between surface parameters after slide diamond burnishing. Measurement Science Review 2018, 18, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczylas, A.; Zaleski, K.; Matuszal, J.; Ciecielag, K.; Zaleski, R.; Gorgol, M. Influence of slide burnishing parameters on the surface layer properties of stainless steel and mean positron lifetime. Materials 2022, 15, 8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V. The correlation between surface integrity and operating behaviour of slide burnished components – a review and prospects. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgioli, F. From austenitic stainless steel to expanded austenite – S phase: formation, characteristics and properties of an elusive metastable phase. Metals 2020, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H. S-phase surface engineering of Fe-Cr, Co-Cr and Ni-Cr alloys. Int Mater Rev 2010, 55, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshiyama, Y.; Mizobata, R.; Miyake, H. Mechanical properties of austenitic stainless steel treated by active screen plasma nitriding. Surf Coat Technol 2016, 307, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshiyama, Y.; Takatera, R.; Maruoka, T. Effect of active screen plasma nitriding on fatigue characteristics of austenitic stainless steel. Materials Transactions 2019, 60, 1638–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschini, L.; Minak, G. Fatigue behaviour of low temperature carburised AISI 316L austenitic stainless steel. Surf Coat Technol 2008, 202, 1778–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Gong, J.; Somers, M.A.J. Effect of low-temperature surface hardening by carburization on the fatigue behavior of AISI 316L austenitic stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A 2020, 769, 138524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinville, J.C.; Villechaise, P.; Templier, C.; Riviere, J.P.; Drouet, M. Plasma nitriding of316L austenitic stainless steel: Experimental investigation of fatigue life and surface evolution. Surf Coat Technol 2010, 204, 1947–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaiwatthana, S.; Li, X.Y.; Dong, H.; Bell, T. Comparison studies on properties of nitrogen and carbon S-phase on low temperature plasma alloyed AISI 316 stainless steel. Surf Eng 2002, 18, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.S.; Che, H.L.; Lei, M.K. Corrosion-fatigue properties of plasma-based low-energy nitrogen ion implanted AISI 304L austenitic stainless steel in borate buffer solution. Surf Coat Technol 2016, 288, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, T.; Xue, Q. Surface nanocrystalization by surface mechanical attrition treatment and its effect on structure and properties of plasma nitrided AISI 321 stainless steel. Acta Materialia 2006, 54, 5599–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemkhi, M.; Retraint, D.; Roos, A.; Garnier, C.; Waltz, L.; Demangel, C.; Proust, G. The effect of surface mechanical attrition treatment on low temperature plasma nitriding of an austenitic stainless steel. Surf Coat Techol 2013, 221, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proust, G.; Retraint, D.; Chemkhi, M.; Roos, A.; Demangel, C. Electron Backscatter Diffraction and Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction Analysis of an Austenitic Stainless Steel Subjected to Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment and Plasma Nitriding. Microscopy and Microanalysis 2015, 21, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).