1. Introduction

Travel and tourism is one of the world’s most relevant industries [

1] and international tourism receipts reached USD 1 trillion in 2022 on the world scale, growing 50% compared to 2021, representing 64% of the pre-COVID pandemic levels. More than 900 million tourists travelled in 2022 doubling the numbers recorded in 2021 and Europe was the largest destination region with 585 million arrivals in 2022 [

1]. In the first three months of 2023, the trend continued to rise and 235 million tourists travelled internationally, i.e. 80% of the pre-pandemic levels and more than double those in the same period of 2022.

In 2022 Spain, with 71.6 million visitors, recorded a 129.5% growth in tourist arrivals respect to 2021, and visitors spent 87,061 million Euros, i.e. 95% of tourism incomes recorded in 2019 [

2,

3]. Tourist sector receipts recorded the same trend and accounted for 12.6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2019, 5.8% in 2020, 8% in 2021 and 12.2% in 2022 [

3]. During the first seven months of 2023, 47.6 million international tourists visited Spain recording ca. 21% increase with respect to the same months of 2022 [

4] and predictions claim that a full recuperation of pre-pandemic tourism visitors and incomes will take place in 2023 (

https://www.mincotur.gob.es/es-es/, September 2023).

International tourists are mostly interested in coastal areas especially because of the “Sun, Sea and Sand (the 3S)” market [

5,

6,

7]. Therefore, beaches and associated tourism worth billions of US dollars and represent a very powerful socio-economic driver that generates investment opportunities and associated employment and income growth [

1,

8,

9]. This is especially observed along the Mediterranean coastal areas that host almost a third of international tourist arrivals [

1]. In Spain, 75% of international visitors are interested in coastal areas and the most visited regions are Catalonia, Balearic and Canarias Islands and Andalusia. Andalusia was visited by 10 million international tourists in 2022 and in the first months of 2023, the trend of incoming tourists increased by 26% with respect to 2022 recording 6.8 million visitors and 12 million visitors are expected for 2023 [

3,

4]. Andalusia is an attractive 3S destination for national tourists too and was visited by a total amount of 23 million of national and international tourists in 2022, a trend confirmed during the first semester of 2023. The most visited provinces were Malaga and Cadiz, the latter recorded 5.4 million in 2022 and 2.4 million visitors in the first semester of 2023 (

https://www.juntadeandalucia.es, September 2023).

Williams (2011), who carried out >4000 questionnaire surveys to beach users in many countries regarding their preferences and priorities, affirmed that visitors are especially interested in five main parameters: safety, water quality, no litter, facilities and scenery, known as the “Big Five” [

10]. In Mediterranean countries and in the Caribbean, users are especially interested in bathing and, therefore, in water quality, safety and no litter [

11], and the latter is the topic of this paper.

Marine litter presents social and economic impacts in coastal and marine areas that include the aesthetic deterioration of scenery and the rejection reactions of beach visitors (that prefer to visit other beaches producing a loss of tourist days), damages to fishing activities and recreational boats, and the safety of bathers that can record injuries because of cutting and sharp objects. Marine litter may produce entanglement, suffocation and ingestion in marine organisms, favors non-native species dispersal and litter plastic items record the adsorption of heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants [

12,

13,

14]. The above-mentioned issues acquire special relevance along the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea, one of the zones most affected by marine litter in the world and this is a topic of concern discussed since the 1970s within the framework of the Barcelona Convention [

15]. According to such report, efforts have to be devoted to the reduction in the production and use of plastics: it is estimated that 6‒10% of the global annual plastic production (ca. 391 million metric tons in 2021,

https://www.statista.com/statistics, September 2023), finally finishes in marine environments where plastics represent the most abundant (ca. 80% of all litter items found along the coast) and potential pollutants [

16] being glass, processed wood, metal, rubber, textiles, and paper other frequent materials [

14,

16]. An important step to reduce coastal pollution consists also in the determination of beach litter sources that can be related to: i) land-based activities, which are responsible for ca. 80% of all beach litter amount and ii) marine-based activities, which account for ca. 20% of beach litter amount [

17,

18]. In the former case, items are discharged on land and are then transported to the marine/coastal environment by winds, rivers, run-off waters, etc., or are directly abandoned on the beach by visitors; in the latter case, items arrive from the sea and are essentially related to maritime transport, fishing activities and off-shore gas/oil extraction [

18]. Finally, efforts have to be devoted to regular and, at times and places, special beach clean-up operations to maintain tourist beaches free of litter [

16] and to the development of sound educational programs at different school levels [

19].

Despite the presence of litter on beaches is an issue of worldwide interest, few papers present the result of beach monitoring programs and relate litter content and abundance with variables such as marine climate, number of visitors, clean-up operations, etc. [

11]. The present paper deals with a beach litter monitoring program carried out during the week-ends of May and June 2021 at two tourist beaches in Cadiz coast (SW Spain) to characterize beach litter items and relationships between beach litter content and the number of visitors and evaluate the efficiency of clean-up operations.

The methodology used in this work can be easily applied in other similar areas and the results obtained employed to promote sound management actions to reduce beach litter pollution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study area

The Cadiz province, on the Atlantic side of Andalusia (Southwestern Spain,

Figure 1), is a densely populated area with 1,246,781 inhabitants recorded in 2022, ca. 9% of them located in the town of Cadiz. In 2022, the province of Cadiz recorded 8 million stay-night visitors, 80% of them located within 30 km from the shoreline [

20] because especially interested in coastal tourism since bathing is possible for several months per year [

21,

22].

The coast shows NW‒SE orientation and is a mesotidal environment with mean neap and spring tides of 1.0 and 3.5m, respectively. It is exposed to both westerly and easterly winds. Westerly winds are associated with Atlantic low-pressure systems and easterly winds, blowing from E to SE directions, are originally formed in the Mediterranean Sea. Concerning morphological beach state, the two investigated coastal sectors are characterized by fine quartz-rich sediments that give rise to dissipative conditions reflected by wide foreshore zones [

23,

24,

25]. Regular beach cleaning operations are daily manually and mechanically carried out early in the morning by local authorities at the investigated beaches from April to October [

25].

Two coastal sectors 100 m in width were investigated in Cadiz town (

Figure 1), both of them being urban beaches according to the terminology of Williams and Micallef [

26]. One sector was located in La Victoria, a very frequented urban beach backed by a promenade with houses, restaurants, hotels, etc., and the other in La Cortadura, a less urbanized area with a smaller number of visitors and backed along the study sector, in the northern part of the beach, by defense walls of an ancient military fort constructed at the beginnings of 1800 and by well-developed dunes ridges in the central and southern area (

Figure 1).

2.2. Data analysis

To study relationships among beach litter, the number of beach visitors and weather conditions, 22 surveys per site were carried out two times per day every Saturday and Sunday from May 2

nd to June 13

th, 2021 at La Victoria and La Cortadura beaches in Cadiz (SW Spain). Following the EA/NALG [

27] technique, surveys were carried out during low tide conditions covering a shore parallel 100-metre long coastal sector and extended to the low water strandline (

Figure 1). The observer reported litter data whilst moving along 5 m apart transects parallel to the coastline in order to cover the dry beach and the foreshore, i.e. from the landward limit of the beach up to the shoreline. Surveys were carried out during the morning usually around 9:00 a.m., which is after beach clean-up operations, and in the evening usually around 9:00 p.m., to assess beach litter content abandoned/left by beach users during the day. During each survey, the number of beach visitors within the investigated areas was counted at 1:00 p.m., i.e. when sites showed the maximum number of visitors.

A wide list of litter items was obtained [

16] by combining three litter classifications from different entities, i.e. the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), OSPAR Commission and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) [

28,

29,

30]. Data gathered were also grouped into 7 categories according to the EA/NALG (2000) methodology [

27] that enables a beach to be graded on four intervals scale ranging from “A” (excellent grade) to “D” (poor grade,

Table 1), taking in consideration that the final score of each site corresponds to the lowest grade obtained, i.e. if any one category scored “D” and all the rest “A”, the overall beach grade is “D”. As an advantage, this method allows to give beach managers a quick view on of the severity of litter impact at a beach site.

Concerning weather conditions, i.e. daily maximum and minimum atmospheric temperature, cloud cover (i.e. sunny, cloudy and rainy days) and wind intensity, were obtained by the Spanish Meteorological State Agency (AEMET).

Statistical analyses were performed with “R” computer program (

http://www.rproject.org/, January 2022) to assess differences in litter abundance between the two sites, litter temporal evolution and evaluate clean-up management efforts. For each data set, the requirements of analysis of variance (ANOVA), i.e. normality and homogeneity of variance, were checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) and Bartlett’s tests, respectively. A square root data transformation was applied and all statistical tests were conducted with a significance level of α = 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

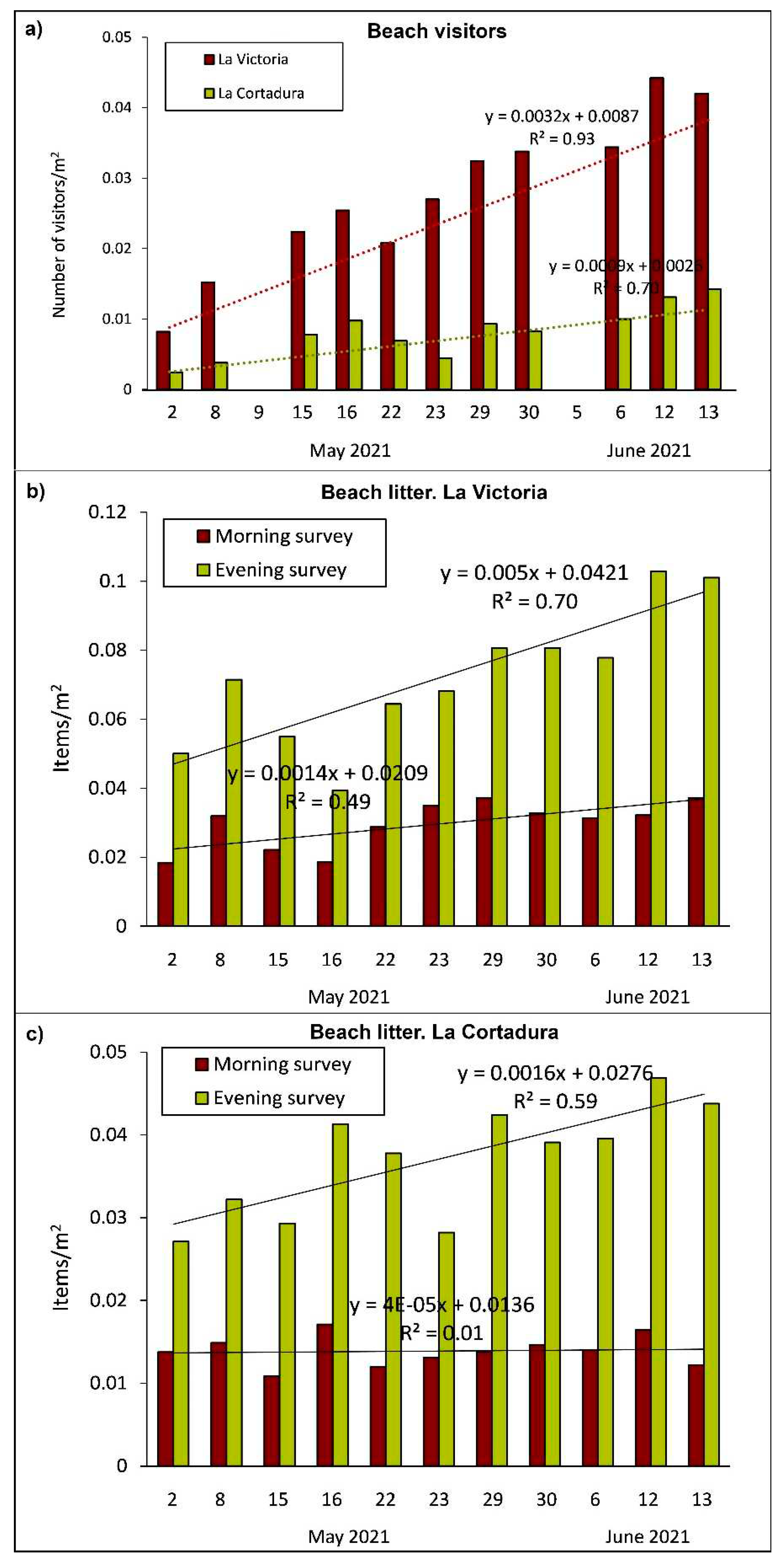

3.1. Beach users’ numbers and weather conditions

Numbers of visitors ranged from 0 to 221 at the beach sector investigated in La Victoria and from 0 to 64 in La Cortadura sector with an average value of 139 (0.028 visitors/m

2) and 36 (0.008 visitors/m

2) visitors for La Victoria and La Cortadura, respectively (

Figure A1a). The days with zero affluence were not considered to calculate the above-presented average values. The number of visitors at La Victoria increased during the study period whereas at La Cortadura the increasing trend was less evident (

Figure A1a). The elevated number of visitors (and their increase) during the study period was related to the good weather conditions recorded characterized by an average maximum temperature of 23°C and an average minimum temperature of 17°C. The weather conditions were always sunny and only two cloudy days were recorded on May, 8

th and June, 12

th and two rainy days took place on May, 9

th and June, 5

th – during such days no beach visitors were recorded (

Figure A1a). During the study period wind velocity ranged from 15 to 37 m s

-1 and approached from both western and eastern directions and negatively influenced the number of visitors at both study sectors only on the 22

nd and 23

rd of May when blew at 37 km/hr.

3.2. Beach litter spatial and temporal distribution

Surveyed beach width (i.e. in the cross-shore direction) not ranged a lot at the two investigated beaches along the study period, i.e. varied from 40 to 50 m at La Victoria beach sector and from 35 to 45 m at La Cortadura. An amount of 8108 items were collected at the two investigated sectors during the study period: 5585 items were recorded at La Victoria from a total of 5000 m2 of surveyed beach surface and 2523 items at La Cortadura from a total of 4500 m2.

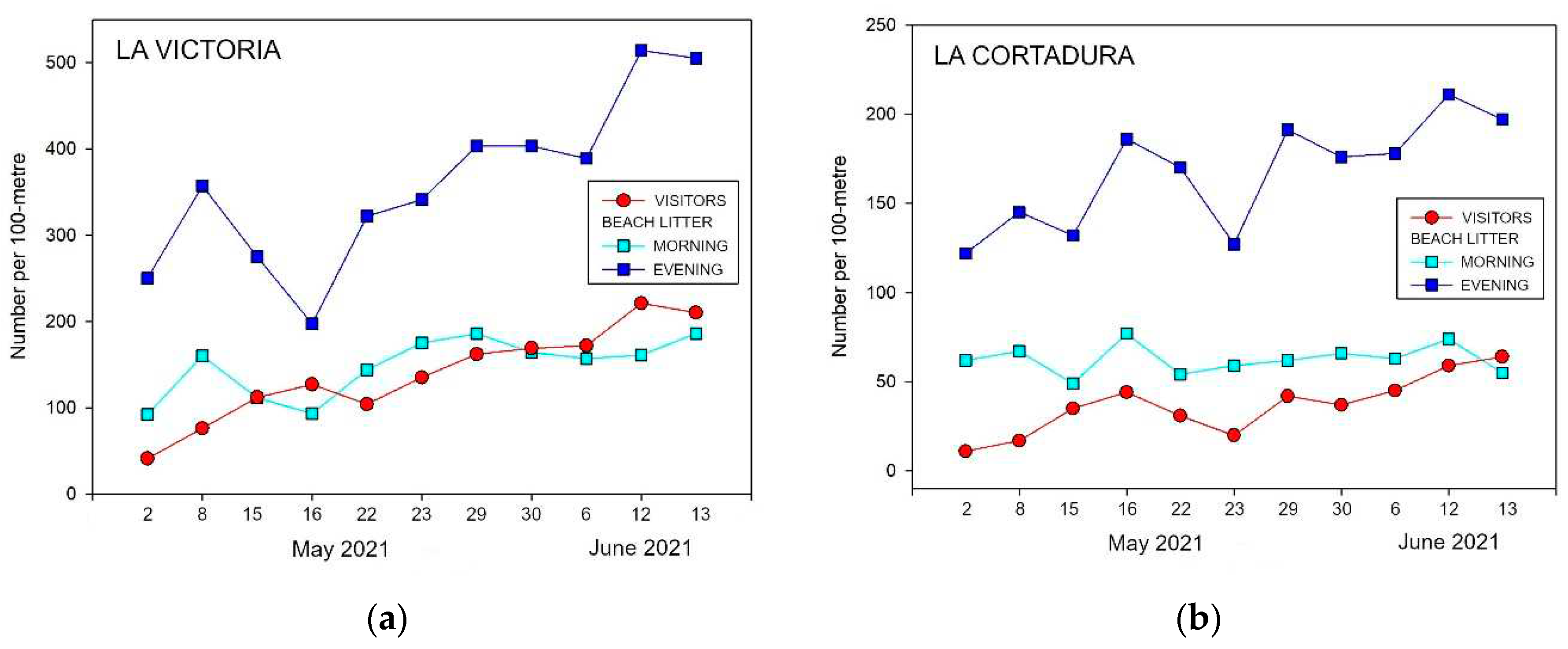

Beach litter abundance at the two study sectors recorded during the morning and evening surveys was presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The amount of litter recorded at the morning beach litter survey represented the quantity of litter observed after the clean-up operations that were daily carried out very early in the morning and the amount recorded at the evening beach survey reflected the number of litter items abandoned/left by beach users during the day.

Concerning La Victoria beach sector, an increase in litter amount was observed for the morning and (especially) the evening survey (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The beach litter amount recorded at the morning survey showed a small and not clear (R

2=0.49) trend with a final increase of litter content of 102.17%. The data collected at the evening survey showed a constant and evident (R

2=0.70) increasing trend and litter amount recorded a 50.5% increase during the study period. Further, for the morning survey, litter amount ranged from 0.018 items m

-2 (or 0.115 items m

-1) on May, 2

nd to 0.037 items m

-2 (or 0.233 items m

-1) on May, 29

th and June, 13

th, with an average value of 0.019 items m

-2 (or 0.118 items m

-1). For the evening survey, litter amount ranged from 0.039 items m

-2 (or 0.246 items m

-1) on May, 16

th to 0.103 items m

-2 (or 0.643 items m

-1) on June, 12

th, with an average value of 0.064 items m

-2 (or 0.397 items m

-1) (

Figure A1b).

Concerning La Cortadura beach sector (

Figure 2 and

Figure A1c), litter content recorded at the evening survey presented a certain (72.95%) and constant (R

2= 0.60) increase. Litter content ranged from 0.027 items m

-2 (0.152 items m

-1) on May, 2

nd to 0.047 items m

-2 (0.264 items m

-1) on June, 12

th, with an average value of 0.020 items m

-2 (0.112 items m

-1). The amount of beach litter observed during the morning survey not greatly changed during the investigated period and ranged from 0.011 items m

-2 (0.061 items m

-1) on May, 15

th, to 0.017 items m

-2 (0.096 items m

-1) on May, 16

th, with an average value of 0.006 items m

-2 (0.035 items m

-1,

Figure A1c).

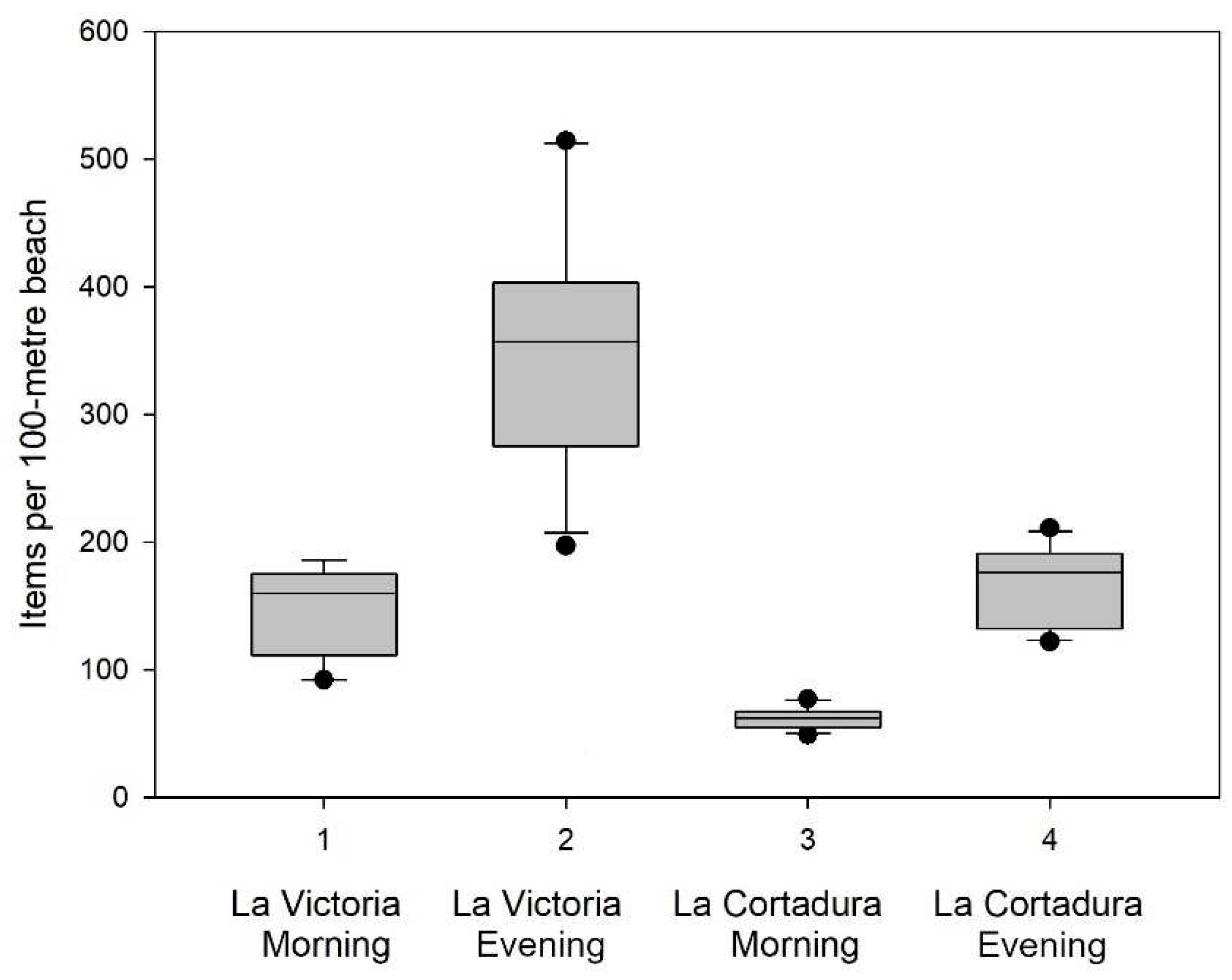

Box plots, which enclose 50% of data, were drawn to represent the abundance of litter: the median value, represented by a single black line, reflects the midpoint of data distribution. Concerning litter density evolution, the amount of litter was higher in the evening than in the morning (

Figure 2). At La Victoria beach, the average number of litter items per beach was 148 items in the morning and 360 in the evening. At La Cortadura beach, the average values were lower, with 62 items in the morning and 167 in the evening (

Figure 2). Statistical analyses revealed that the observed differences in litter abundance at the two beaches do not depend on sampling time (P=0.5). However, there are significant differences in litter abundance between both beaches and also for sampling time (p values<0.001).

An increase of beach litter can be observed during the study period that covered the beginning of the summer season due to the increase of beachgoers. Concerning seasonal trends in litter abundance, greater quantities of litter related to beach users are especially observed during summer compared to other seasons [

31]. This increase in litter on beaches is noticeable, especially in tourist areas. For example, in Alicante (SE Spain), some litter items related to beach users tripled their abundance in summer, such as cigarette butts [

16] despite the increase of the cleaning efforts performed during the summer season. Beach litter in Sarayköy Beach (SE Black Sea) also recorded higher litter densities during summer than the rest of the year [

32].

3.3. Litter Grade

The EA/NALG [

27] protocol (

Table 1) was used to determine Litter Grade for the two investigated sites and for the 22 surveys carried out at each site (

Table 2).

Despite La Victoria beach scored “A” (i.e. “Very good” conditions) for almost all litter categories and surveys, the total score “B” (i.e. “Good”) was obtained for most of the surveys (17 out of 22) and “C” (“Fair”) for the rest of surveys, all of them (but one) being evening litter data (

Table 2). It is interesting to highlight that “B” score was always related to “General litter” and “C” to “Harmful litter” such as broken glass. Summing up, the overall Litter Grade for La Victoria was “C” essentially related to “General litter” and especially to “Harmful litter” categories, this way confirming the important effect of beach visitors on litter amount recorded, e.g. the last two “C” values were observed in correspondence of a high number of visitors recorded on 12

th and 13

th June 2021, and also evidence the relevance of beach clean-up programs that allow to considerably reduce beach pollution, as confirmed because “B” scores were recorded after clean-up operations.

La Cortadura beach presented a very similar trend to La Victoria. Despite “A” was the most observed score, “B” (“i.e. “Good”) and “C” (“Fair”) scores were essentially recorded for “General litter” and “Harmful litter” (Broken glass), respectively. Overall Litter Grade for La Cortadura was “C” and it is interesting to highlight that this negative score was not only exclusively reordered in the evening but also during the morning surveys (

Table 2) evidencing the low efficiency of clean-up operations, especially for the category “Harmful litter”.

In the study elaborated in 2018 by Asensio-Montesinos et al. [

33], La Victoria and La Cortadura beaches also obtained a Grade “C” using the EA/NALG [

27] protocol. In the case of La Victoria, this was due to sewage-related debris, general litter and broken glass. In the case of La Cortadura, it was due to broken glass [

33]. The main reasons for poor scores for these two beaches are still present and are the same as when they were first assessed: the abundance of general and harmful litter.

3.4. Beach litter composition

The most numerous litter items at each one of the investigated sites are presented in

Table 3. At both sites, Cigarette butts were the most abundant items accounting for 42.61% and 20.53% of the total amount for La Victoria and La Cortadura, respectively. They were followed by Hard plastic pieces (0−2.5 cm) that constituted 16.01% of all items at La Victoria and 13.83% at La Cortadura. Other items common to both sites represented less than 5% and included Hard (2.5−50 cm) and Film (0−2.5 cm) plastic pieces (

Table 3). Concerning less frequent items, La Victoria recorded plastic cups (2.20%), plastic bags (1.15%) and glass bottles (0.98%) and La Cortadura presented cloths (4.88%), foamed plastic pieces (0−2.5 cm, 4.43%), aluminum foil wrappers (3.80%) and glass fragments (0−2.5 cm, 3.53%).

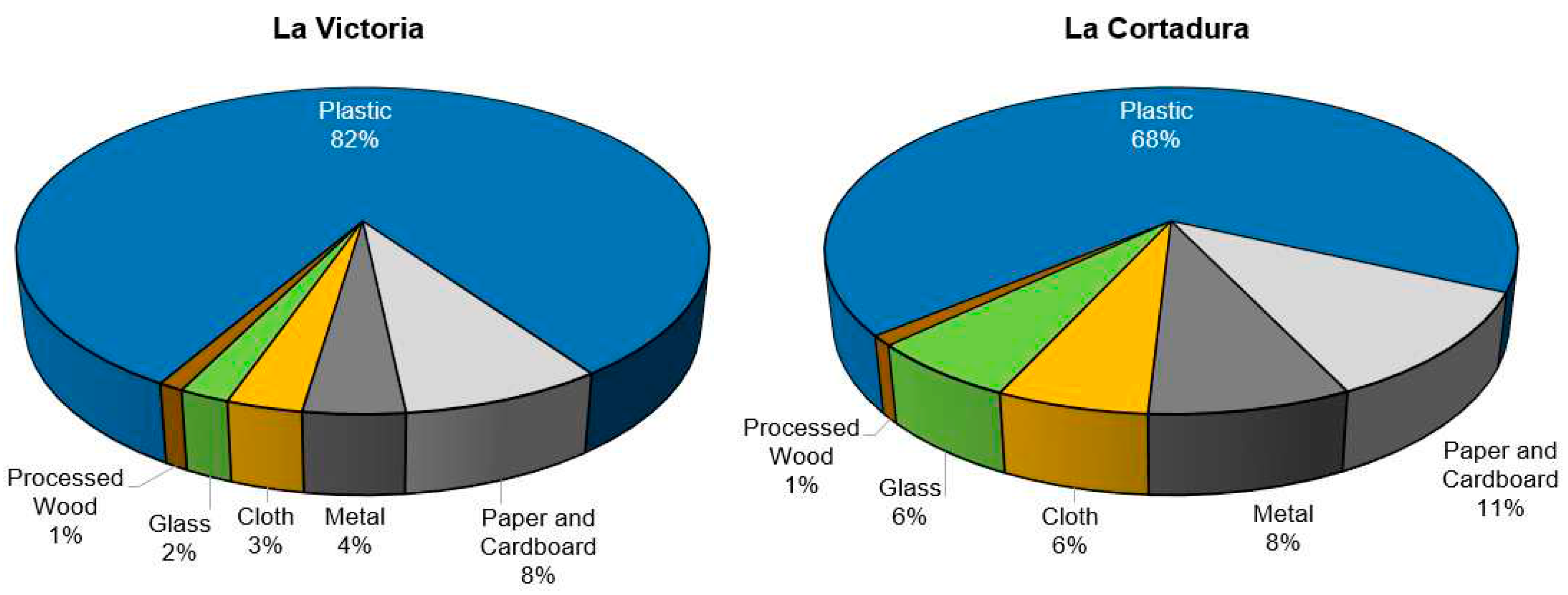

Considering all surveys carried out at each site, litter composition per type of material was similar at La Victoria and La Cortadura beaches (

Figure 4). Plastic items were the most abundant and accounted for 82% at La Victoria and 68% at La Cortadura, followed by paper/cardboard, metal and cloth (that were more abundant at La Cortadura) and glass and wood processed items (

Figure 4).

Three plastic items were the most abundant, and in the same order, at each beach. Cigarette butts accounted for 51.87% and 30.03% of all plastics at La Victoria and La Cortadura sectors, respectively, followed by Hard plastic pieces (0−2.5 cm) with ca. 20% at each beach sector and Hard plastic pieces (between 2.5 cm‒50 cm), which amount ranged from 5 to 7%. They were followed by different items which amount was lower than ca. 4% and 7% of all items at La Victoria and La Cortadura sectors, respectively, i.e. Film Plastic pieces between 0 and 50 cm, Hard plastic cups and Foamed plastic food containers. Followed by caps/lids (2.5%) in La Cortadura, bags (1.4%) in La Victoria and Crisp /sweet packets and lolly sticks, which are found in smaller proportions in both beaches (

Table 4).

The type and quantity of litter varies according to the distance from the shoreline. For example, in La Cortadura, it was observed as in the areas closest to the shore, items such as ropes and nets predominate.

Results obtained in this paper confirmed data recorded in previous studies in Cadiz beaches that observed as plastic was the most abundant material followed by cigarette butts and hard plastic pieces [

25,

33]. In Morocco, Mediterranean beaches also have plastic as the main material abandoned and other common items were bottle caps, crisps packets/sweets wrappers and cigarettes butts [

34].

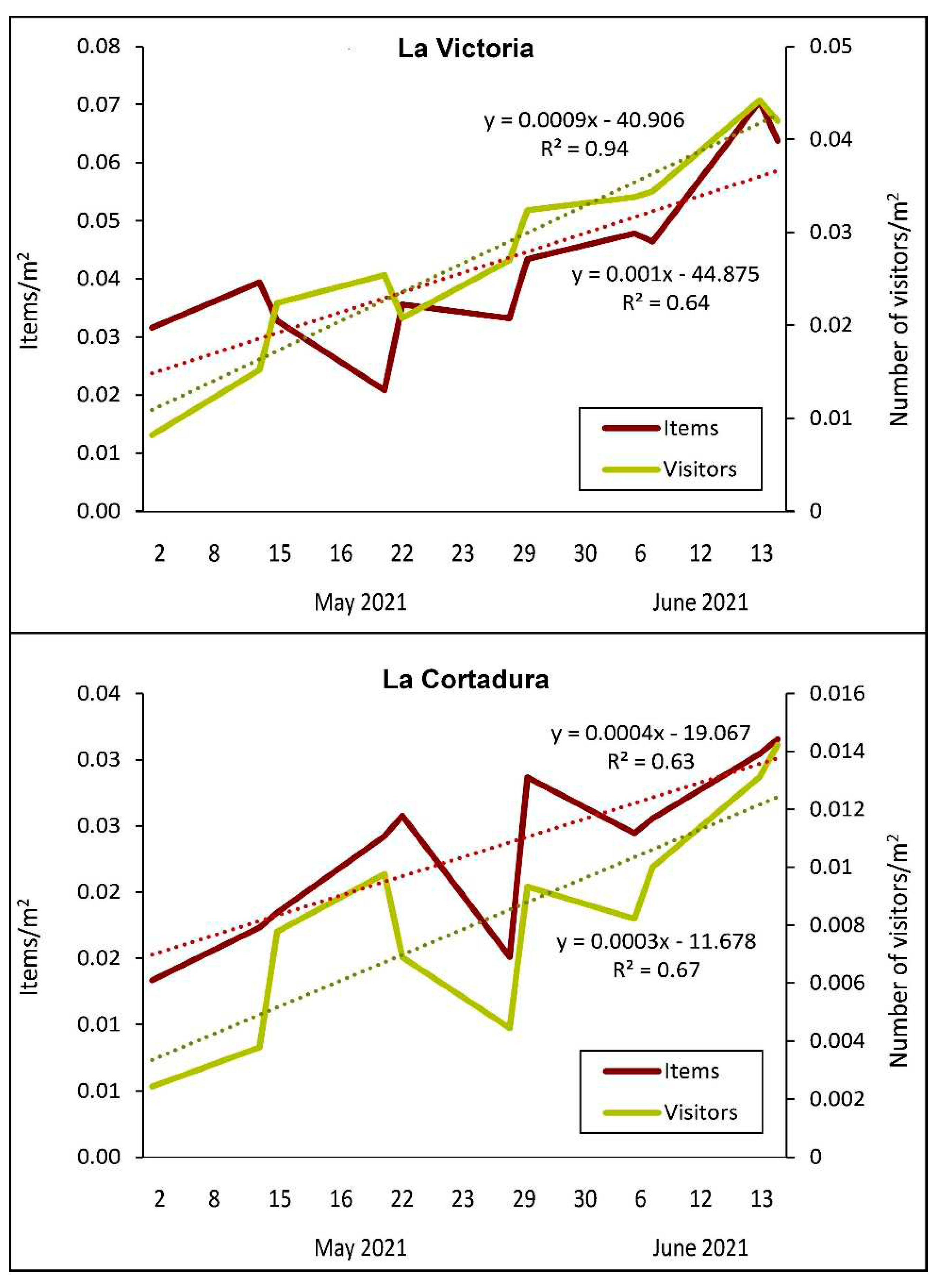

3.5. Litter content versus beach visitors and clean-up operations

The progressive enhancement of beach litter content recorded at the evening survey reflected the progressive increase in the number of beach visitors during the study period (

Figure A2 and

Figure 3) due to the improvement of good weather conditions and the beginning of summer holidays.

In La Victoria sector (

Figure A2 and

Figure 3), beach litter content observed during the study period at both morning and evening surveys recorded an increasing trend but with different values. At La Cortadura (

Figure A2b and

Figure 3), an increase in litter amount during the study period was only showed by the evening data. Such behavior evidenced as, despite the increase in litter amount recorded during the evening survey, clean-up operations were able to keep almost constant the quantity of litter at La Cortadura but it was not the case for La Victoria where it seems that clean-up efforts were less effective especially when litter content was > 0.06 items m

-2 (

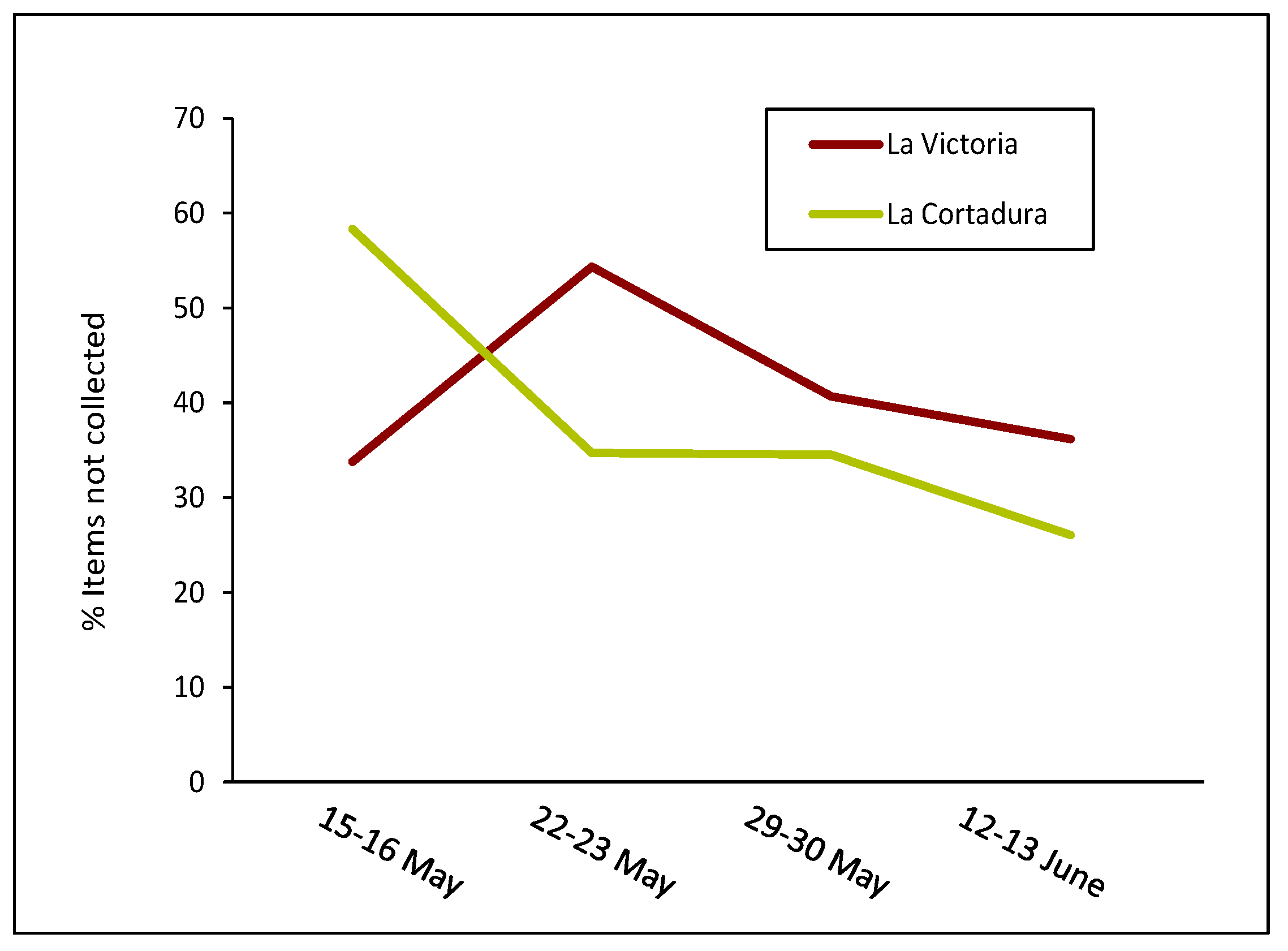

Figure A2). The percentage of items not collected presented different and opposite values for the two beaches investigated for the 15-16 and 22-23 May surveys and then decreased in both sectors with La Victoria showing higher values than La Cortadura (

Figure 5).

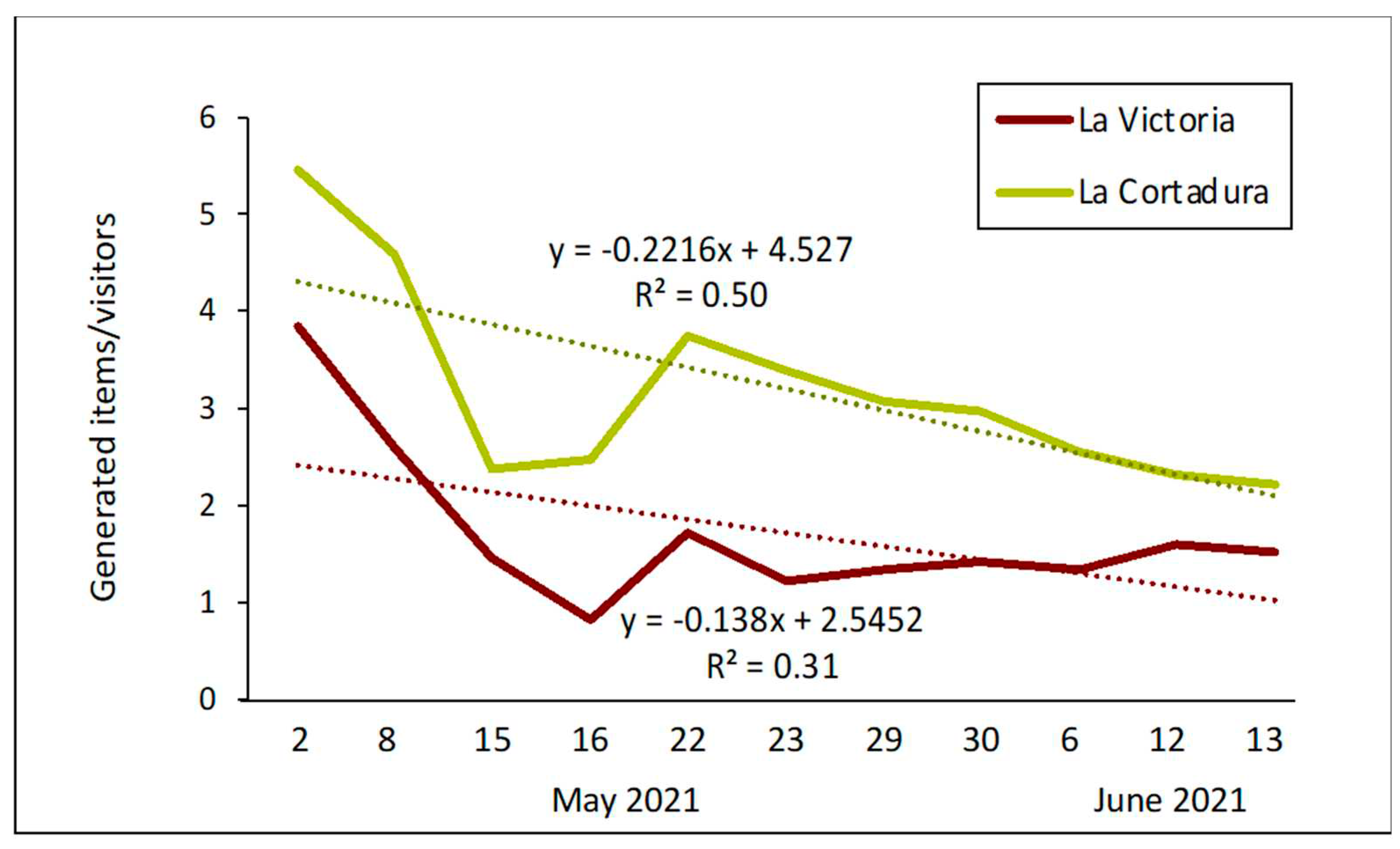

The litter daily generated in the beach, i.e. the litter amount recorded at the evening sampling

minus the amount recorded at the morning sampling, was divided by the number of users observed on the considered day (

Figure 6). It can be observed that, at La Victoria, each user was responsible for 1 to 4 daily accumulated litter items during the study period, while at La Cortadura, each user is responsible for 2 to 6 litter items approximately. In both cases this trend decreased due to an increase in the efficiency of cleaning operations (

Figure 5).

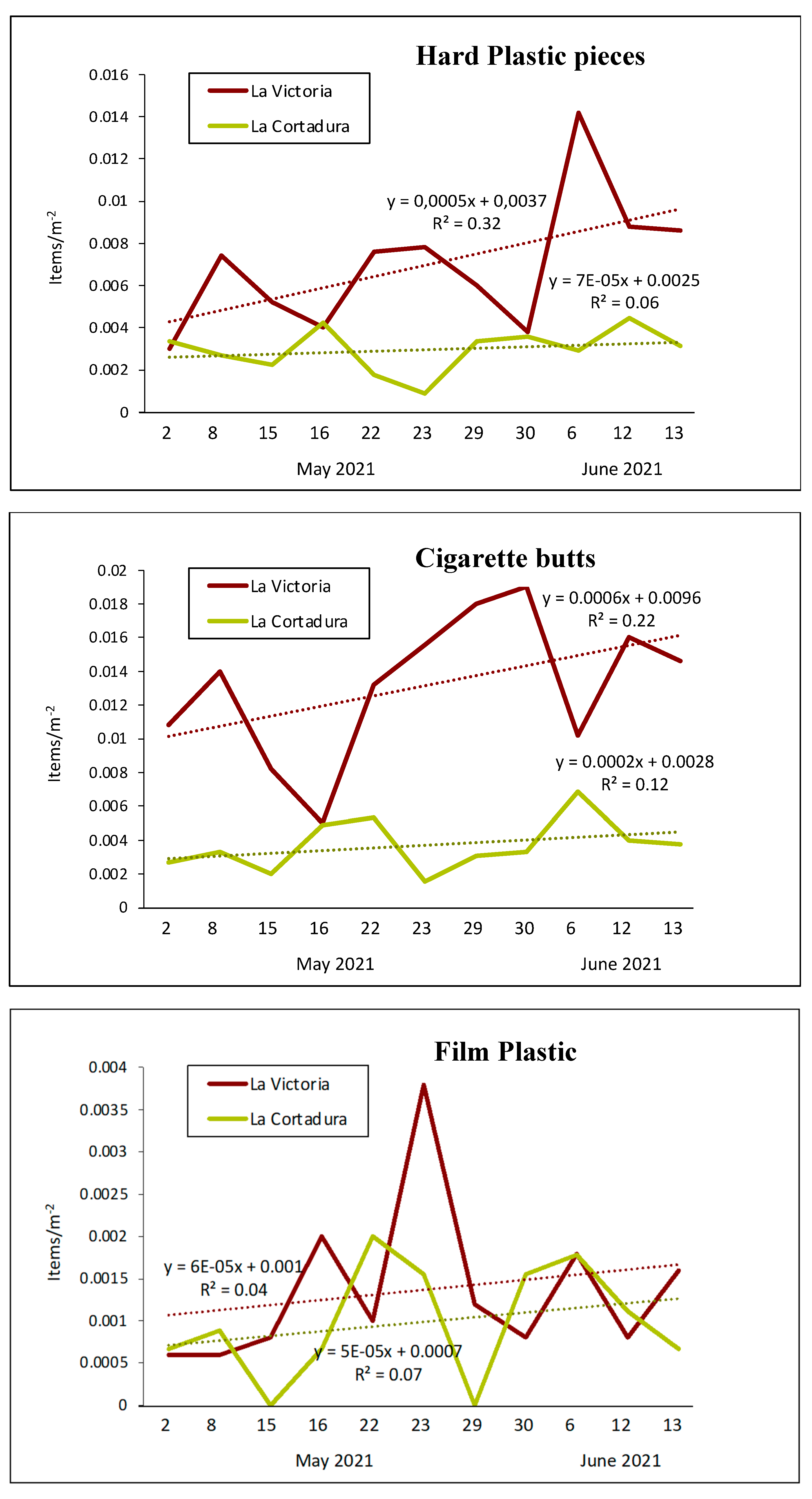

The increase in beach litter content recorded in La Victoria sector (

Figure A3) was related to the increase of small litter items such as Hard and Film plastic pieces (0‒2.5 cm) and Cigarette butts that probably pass through the meshes of the beach cleaning machines that had a mesh size of 2 cm, permitting some but not all cigarette butts to be picked up [

25], therefore the present efficiency of mechanical operations in collecting small items is low [

35]. Further, results obtained have a certain level of inaccuracy since there is a margin of error in counting small items that can be easily buried and may remain for several months on the same beach or even move to other beaches [

36].

As previously demonstrated by Williams et al. (2016) and Asensio-Montesinos et al. (2020), the bulk of litter in Cadiz beaches generally is distributed in the high-tide water level and the backshore area [

25,

33]. This spatial distribution of litter on beaches has also been observed in other countries such as Korea [

37] and Japan [

38]. The final part of the beach usually always accumulates a lot of litter (

Figure A4). It has been observed by Williams et al. (2016) that this litter accumulation may be due to the fact that cleaning machines are not able to move close to walls and pathways so items accumulated there were not collected [

25]. In addition, as previously observed, cleaning machines are less effective for small litter items than for general-sized litter [

35].

Differences between surveys were also documented in other Mediterranean beaches, linked to marine storms and river discharges, frequency and modalities of clean-up operations, beach user abundance and beach typology [

39]. Numerous researchers have related litter amount recorded in urban beaches to local population density. Some of them were Ariza et al. [

35], Williams et al. [

25] and Asensio-Montesinos et al. [

16] on different coasts of Spain, Maziane et al. (2018) in beaches from Morocco [

40], Topçu et al. (2013) in Turkish Western Black Sea Coast [

41] or Katsanevakis and Katsarou (2004) in Greece [

42]. Generally, litter amount is directly related to the number of beach users and inversely related to its geographical distance to a population center [

43,

44]. Last, changes in the number of beach visitors due to seasonality increase the amount of litter and such seasonal variability makes it difficult to establish a proper waste management plans that includes facilities aimed at prevention and recycling [

35].

4. Conclusions

The differences recorded between the two beaches investigated were remarkable, both in terms of abundance and type of litter. The amount of litter present at La Victoria doubled from the beginning to the end of the study, while at La Cortadura the increase was not so significant. This was due to the difference in the number of visitors and the activities carried out in each beach. In addition, differences in litter amount recorded at the morning and the evening surveys were very remarkable and related to the number of users that visited the beach.

The presence of litter is linked to the presence of users and, in turn, the presence of users is linked to favorable meteorological conditions. On days with worse weather conditions (e.g. windy, rainy or cloudy days), the absence/decrease of users was evident. On the contrary, sunny days resulted in a higher number of visitors, which evidently increased the number of beach litter items.

In terms of litter composition, as observed in previous studies, plastic was the most common material identified (80% at La Victoria and 68% at La Cortadura) and was mostly represented by cigarette butts and small fragments of hard plastic pieces.

The cleaning services on both beaches are very effective against medium and large size items however, most of the small fragments (regardless of the material) remain in the beach surface or buried in the sand after beach cleaning operations. For this reason, one of the main problems in these areas is the presence of cigarette butts and glass fragments. Concerning the Litter Grade, category “C” (“Fair”) was mainly due to the presence of hazardous items. This highlights a certain degree of mismanagement during past years that allowed the accumulation of hazardous items. Therefore, efforts must be devoted to make beaches less dangerous for users and consequently improve Litter Grade scores. Probably, the removing of small hazardous items, such as glass fragments, and in general of small items, has to be carried out manually because it seems that cleaning machines are presently unable. The large amount of small items left behind by cleaning machines is a real problem because such items persist on beaches during long times. This study shows that even if beaches are cleaned every day, they are still contaminated by different litter typologies, especially small sized items.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A. and P.A.; methodology, G.A.; software, F. A.−M.; validation, G.F.G. and F. A.−M.; formal analysis, G.F.G.; investigation, G.F.G.; resources, P.A.; data curation, G.F.G. and F. A.−M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.F.G.; writing—review and editing, G.A. and P.A.; visualization, F. A.−M.; supervision, G.A.; project administration, P.A.; funding acquisition, G.A. and P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided on request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work is a contribution to the “Geosciences” PAI Andalusia (Spain) Research Group RNM-373.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

(a) Numbers of beach visitors during the study period at the investigated sectors in La Victoria and La Cortadura beaches. Regression lines and R2 values are also presented. Beach litter amount at La Victoria (b) and La Cortadura (c) recorded at the morning and the evening surveys. Regression lines and R2 values are also presented.

Figure A1.

(a) Numbers of beach visitors during the study period at the investigated sectors in La Victoria and La Cortadura beaches. Regression lines and R2 values are also presented. Beach litter amount at La Victoria (b) and La Cortadura (c) recorded at the morning and the evening surveys. Regression lines and R2 values are also presented.

Figure A2.

Figure A2. Normalised beach litter content recorded during the evening survey versus normalised number of visitors at La Victoria and La Cortadura beach sectors.

Figure A2.

Figure A2. Normalised beach litter content recorded during the evening survey versus normalised number of visitors at La Victoria and La Cortadura beach sectors.

Figure A3.

Figure A3. Evolution during the study period in the content of different small litter items at la Victoria and La Cortadura beaches. Hard plastic pieces (between 0−2.5 cm), Cigarette butts and Film plastic pieces (0−2.5 cm).

Figure A3.

Figure A3. Evolution during the study period in the content of different small litter items at la Victoria and La Cortadura beaches. Hard plastic pieces (between 0−2.5 cm), Cigarette butts and Film plastic pieces (0−2.5 cm).

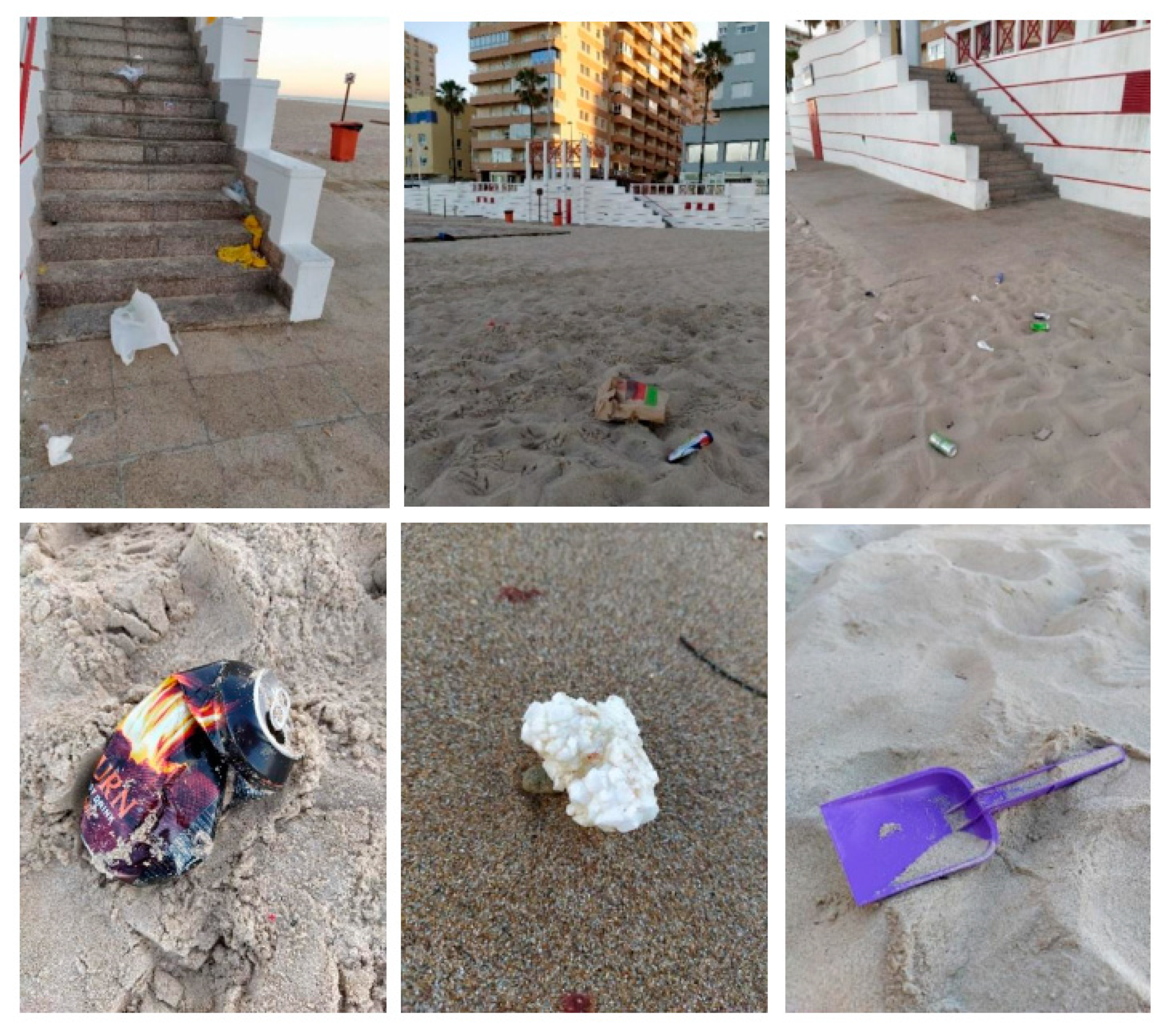

Figure A4.

Figure A4. Some of the most common litter items observed during the study.

Figure A4.

Figure A4. Some of the most common litter items observed during the study.

References

- World Tourism Organization (2023), International Tourism Highlights, 2023 Edition – The impact of COVID-19 on tourism (2020–2022), October 2023, UNWTO, Madrid, DOI: https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284424986. [CrossRef]

- INE, 2022. Cuenta Satélite del Turismo de España (CSTE) Serie 2016 – 2021. Notas de Prensa 22 diciembre de 2022, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Madrid. 4p.

- INE, 2023a. Estadística de Movimientos Turísticos en Fronteras (FRONTUR), Diciembre 2022 y año 2022. Notas de Prensa 2 febrero de 2023, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Madrid. 11p.

- INE, 2023b. Estadística de Movimientos Turísticos en Fronteras (FRONTUR), Julio 2023. Notas de Prensa 1 septiembre de 2023, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Madrid. 6p.

- Dodds, R.; Kelman, I. How climate change is considered in sustainable tourism policies: A case of the Mediterranean islands of Malta and Mallorca. Tour. Rev. Int. 2008, 12, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.R. The economic value of America’s beaches—a 2018 update. Shore & Beach 2018, 86(2), 3–13.

- Alipour, H.; Olya, H.G.; Maleki, P.; Dalir, S. Behavioral responses of 3S tourism visitors: Evidence from a Mediterranean Island destination. Tour. Manag. Perspec. 2020, 33, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.B. Marine Pollution, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Pranzini, E.; Anfuso, G.; Botero, C.M.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A.; Mooser, A. An Attempt to Characterize the “3S” (Sea, Sun, and Sand) Parameters: Application to the Galapagos Islands and Continental Ecuadorian Beaches. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. Definitions and typologies of coastal tourism beach destinations. In Disappearing destinations: Climate change and future challenges for coastal tourism Wallingford UK: Cabi. 2011, pp. 47-65.

- Botero, C.M., Anfuso, A., Williams, A.T., Zielinski, S., Silva, C.P., Cervantes, O., Silva, L., Cabrera, J.A. Reasons for beach choice: European and Caribbean perspectives. Journal of Coastal Research, 2013, Special Issue No. 65, pp. 880-885, ISSN 0749-0208. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Lebreton, L.C.M.; Carson, H.S.; Thiel, M.; Moore, C.J.; Borerro, J.C.; Galgani, F.; Ryan, P.G.; Reisser, J. Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans: More than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krelling, A.P.; Williams, A.T.; Turra, A. Differences in perception and reaction of tourist groups to beach marine debris that can influence a loss of tourism revenue in coastal areas. Mar. Policy 2017, 85, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Stöfen, O. Marine litter. In Handbook on Marine Environment Protection; Salomon, M., Markus, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 447–461. ISBN 9789944245326. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP/MAP. Updated Report on Marine Litter Assessment in the Mediterranean, 2015. Agenda item 4: Enhanced knowledge on amounts, sources and impacts of Marine Litter, including micro-plastics. UNEP(DEPI)/MED WG.424/Inf.6, 19–20 July 2016, p. 90.

- Asensio-Montesinos, F.; Anfuso, G.; Randerson, P.; Williams, A.T. Seasonal comparison of beach litter on Mediterranean coastal sites (Alicante, SE Spain). Ocean & Coastal Management, 2019, 181, 104914. [CrossRef]

- Allsopp, M.; Walters, A.; Santillo, D.; Johnston, P. Plastic Debris in the World's Oceans. Greenpeace, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2006, pp. 44.

- Bergmann, M.; Gutow, L.; Klages, M. (Eds.) Marine Anthropogenic Litter. Springer. 2015.

- Bettencourt, S.; Costa, S.; Caeiro, S. Marine litter: A review of educative interventions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INE, 2023c. Coyuntura Turística Hotelera (EOH/IPH/IRSH). Notas de Prensa 22 septiembre de 2023, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Madrid. 12p.

- Anfuso, G.; Gracia, F.J. Morphodynamic characteristics and short-term evolution of a coastal sector in SW Spain: implications for coastal erosion management. J. Coast. Res. 2005, 21(6), 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. T.; Pond, K.; Ergin, A.; Cullis, M. J. The hazards of beach litter. In Coastal hazards, 2013, 753-780.

- Wright, L.D.; Short, A.D. Morphodynamic variability of beaches and surfzones: a synthesis. Mar. Geol. 1984, 56, 92–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masselink, G., Short, A.D. The effect of tide range on beach morphodynamics and morphology: a conceptual beach model. J. Coast. Res. 1993, 9, 785–800.

- Williams A.T.; Randerson, P.; Di Giacomo, C.; Anfuso, G.; Macias, A.; Perales, J.A. Distribution of beach litter along the coastline of Cádiz, Spain. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 107(1): 77–87. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T.; Micallef, A. (eds). Beach Management: Principles and practices. Earthscan, London, 2009, pp. 480. 2009.

- EA/NALG. Assessment of Aesthetic Quality of Coastal and Bathing Beaches. Monitoring Protocol and Classification Scheme. Environment Agency and The National Aquatic Litter Group, London, 2000, p. 15.

- Cheshire, A.; Adler, E. UNEP/IOC guidelines on survey and monitoring of marine litter. 2009.

- OSPAR Commission. Guideline for Monitoring Marine Litter on the Beaches in the OSPAR Maritime Area; OSPAR: London, UK. 2010.

- Opfer, S.; Arthur, C.; Lippiatt, S. NOAA Marine Debris Shoreline Survey Field Guide; US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program: Washington, DC, USA. 2012.

- Watts, A. J.; Porter, A.; Hembrow, N.; Sharpe, J.; Galloway, T.S.; Lewis, C. Through the sands of time: beach litter trends from nine cleaned North Cornish beaches. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 228, 416-424. [CrossRef]

- Aytan, U.; Sahin, F.B.E.; Karacan, F. Beach litter on Sarayköy Beach (SE Black Sea): density, composition, possible sources and associated organisms. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2019, 20(2), 137-145. [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Montesinos, F.; Anfuso, G.; Oliva Ramírez, M.; Smolka, R.; García Sanabria, J.; Fernández Enríquez, A.; Arenas, P.; Macías Bedoya, A. Beach litter composition and distribution on the Atlantic coast of Cádiz (SW Spain). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 34, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachite, D.; Maziane, F.; Anfuso, G.; Williams, A.T. Spatial and temporal variations of litter at the Mediterranean beaches of Morocco mainly due to beach users. Ocean & Coastal Management, 2019, 179, 104846. [CrossRef]

- Ariza, E.; Jiménez, J.A.; Sardá, R. Seasonal evolution of beach waste and litter during the bathing season on the Catalan coast. Waste Management, 2008, 28(12), 2604-2613. [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Montesinos, F.; Anfuso, G.; Williams, A.T.; Sanz-Lázaro, C. Litter behaviour on Mediterranean cobble beaches, SE Spain. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Hong, S.H.; Shim, W.J.; Eo, S. Characteristics of meso-sized plastic marine debris on 20 beaches in Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 123(1-2), 92-96. [CrossRef]

- Kei, K. Beach Litter in Amami Islands, Japan. South Pacific Studies, 2005, 26(1), 15-24.

- Asensio-Montesinos, F.; Anfuso, G.; Aguilar-Torrelo, M.T.; Oliva Ramírez, M. Abundance and temporal distribution of beach litter on the coast of Ceuta (north Africa, Gibraltar strait). Water, 2021, 13(19), 2739. [CrossRef]

- Maziane, F.; Nachite, D.; Anfuso, G. Artificial polymer materials debris characteristics along the Moroccan Mediterranean coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 128, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topçu, E. N.; Tonay, A. M., Dede, A., Öztürk, A. A., & Öztürk, B. (2013). Origin and abundance of marine litter along sandy beaches of the Turkish Western Black Sea Coast. Marine Environmental Research 85, 21–28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Katsarou, A. Influences on the distribution of marine debris on the seafloor of shallow coastal areas in Greece (Eastern Mediterranean). Water, air, and soil pollution, 2004, 159, 325-337. [CrossRef]

- Gabrielides, G.P.; Golik, A.; Loizides, L.; Marino, M.G.; Bingel, F.; Torregrossa, M.V. Man-made garbage pollution on the mediterranean coastline. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1991, 23, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, A.; Cullen, M. Marine debris on northern New South Wales beaches (Australia): sources and the role of beach usage. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1997, 34(5), 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).