Submitted:

25 December 2023

Posted:

26 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Instruments Assessing Attachment Disorders

- Disturbance Attachment Interview (DAI): The DAI, developed by Smyke and Zeanah in 1999 [15], is a semi-structured interview consisting of 12 items administered to a primary caregiver or someone well-acquainted with the child. It aims to assess signs related to disordered attachment and symptoms of both RAD and DSED. The items cover inhibited behaviors for RAD diagnosis, such as the absence of a preferred adult, lack of comfort-seeking, and limited social reciprocity. For DAI diagnosis, disinhibited behaviors are evaluated, including a lack of caution with strangers and a willingness to go with unknown adults. Scoring for the DAI ranges from 0 to 10 for RAD and 0 to 8 for DSED [16].

- The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA): Seim (2019) [17] developed the PAPA, a caregiver-reported questionnaire designed for preschoolers aged 2-8 years. This assessment evaluates RAD and DSED based on DSM-5 criteria. RAD classification requires meeting RAD criteria A1 and one or more criteria B. For DSED, participants must meet at least two DSED criteria [18].

- Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder Assessment (RADA): Developed by Lehmann et al. in 2018 [21], the RADA assessment follows DSM-5 criteria. It features 11 items for RAD and 9 for DSED. TAR includes two factors: incapacity to seek/accept comfort and low socioemotional responsiveness/emotional dysregulation, while DSED has one factor related to indiscriminate behaviors [22].

- Development and Well-Being Assessment RAD/DSED (DAWBA RAD/DSED): A section within the DAWBA interview [23] comprises 14 items derived from the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment for RAD/DSED. These items assess social behaviors of concern to caregivers, scoring from 0 to 10 for TAR and 0 to 18 for DSED [24].

- RAD Questionnaire (Questionnaire Disorder Attachment Reactive): The RAD Questionnaire, developed by Minnis in 2002 [25], consists of 17 items evaluating both reactive and disinhibited attachment disorders concurrently. Scores on this questionnaire range from 0 to 51, with higher scores indicating more severe attachment disorder symptoms [26].

1.2. The current study

2. Materials and Methods

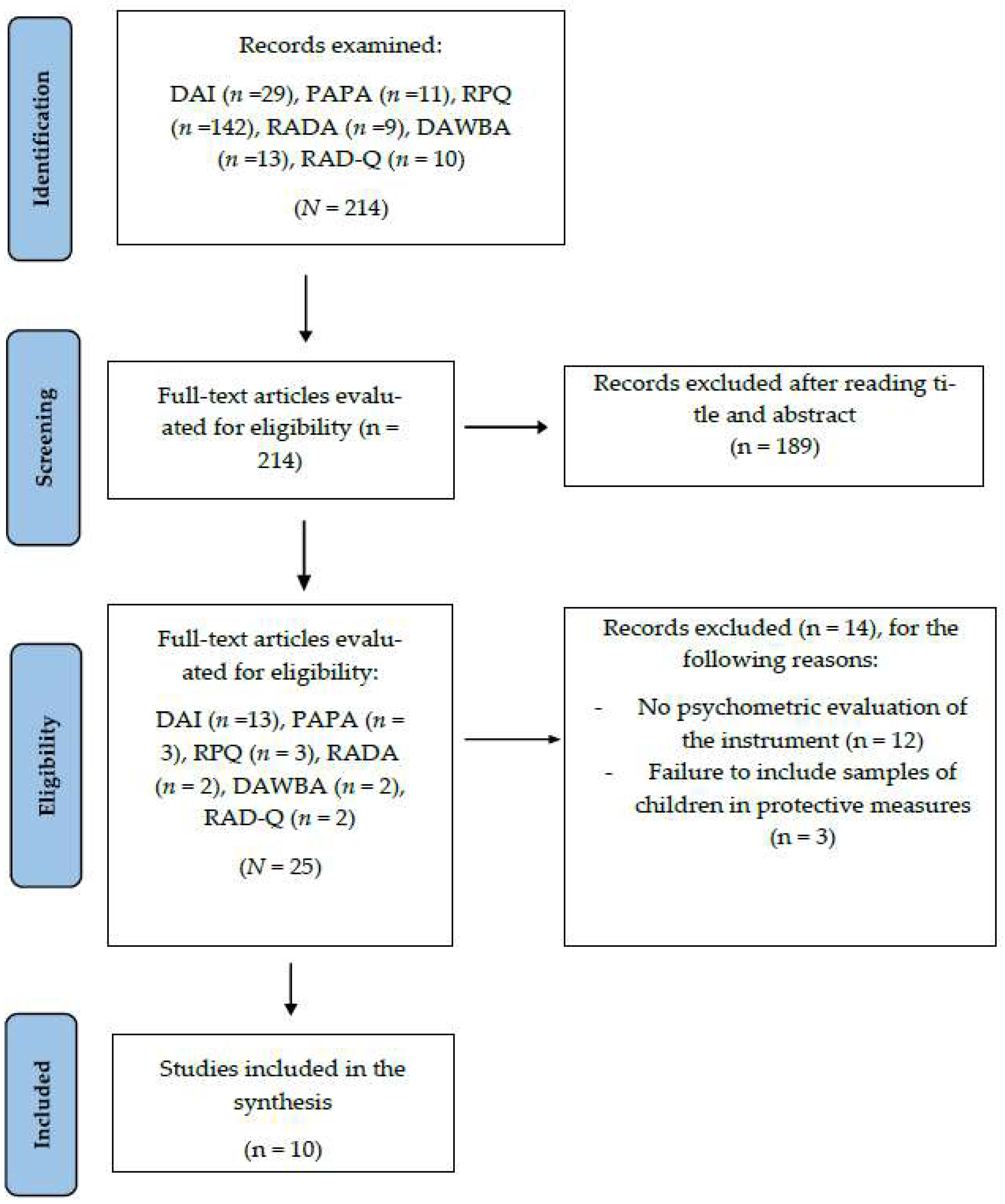

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Procedure

2.4. COSMIN Checklist for Systematic Reviews of PROMs

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the samples of the studies analyzed

3.2. Methodological and measurement quality of the results of the instruments

- Disturbance Attachment Interview (DAI): In most cases, the focus is on structural validity and internal consistency. In this regard, two out of the four studies conducted structural validity analyses, with both employing confirmatory factor analysis. However, one of them (Kliewer-Neumann, et al., 2015) had a small sample size (< 5 times the number of items). Regarding criterion validity, one study examined it (Kliewer Neumann, et al., 2015). Concerning hypothesis testing and construct validity, various tests were conducted, but without establishing a priori hypotheses.

- The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assesment (PAPA): A study conducted by Seim et al. (2020) assessed the psychometric properties of the PAPA, focusing on criterion validity, measurement error, and discriminant validity. The study yielded favorable results regarding the two-factor factorial structure (inhibited and disinhibited) as well as discriminant validity. It was observed that RAD and DSED were distinct constructs from each other and from other mental health issues.

- Relationship Patterns Questionnaire (RPQ): A study conducted by Schöder et al. (2019) assessed the internal consistency and measurement error of the RPQ. The study reported adequate values for internal consistency (overall scale α = .82; inhibition subscale α = .75; disinhibition subscale α = .81). In terms of criterion validity analysis and responsiveness, calculations were performed in the study by Schröder et al. (2019). Significant Area Under the Curve (AUC) values were obtained, indicating diagnostic accuracy, with lower accuracy observed in boys compared to girls. The study also proposed diagnostic cut-off points.

- Reactive Attachment Disorder and Deshinhibited Social Engagement Disorder Assessment (RADA): One study assessed the psychometric properties of the RADA (Lehmann, Monette et al., 2020). It was focused on analyzing its factorial structure by proposing a three-construct factorial solution (DSED: indiscriminate behaviors with strangers; RAD1: inability to seek/accept comfort; RAD2: withdrawal/hypervigilance). The study also examined internal consistency and criterion and construct validity.

- Developmental and Well-Being Assessment RAD/DSED (DAWBA RAD/DSED): Lehmann et al. (2016) examines structural validity through a confirmatory factor analysis with two factors, consistent with the DSM-5 definition. Regarding construct validity, the study aimed to differentiate difficulties between SDQ, DSED, and RAD.

- RAD Questionnarie: Minnis et al. (2002) assessed structural validity, internal consistency, temporal consistency, measurement error, and criterion validity. Adequate indicators were obtained in all cases. Therefore, satisfactory internal consistency for the tool's use in research settings (α= 0.7) was achieved. The relationship between the questionnaire and the SDQ was tested, yielding very high correlations, which, in general terms, may not necessarily be positive.

3.3. Criteria measurement: quality of the instruments

| Study and Instrument | Structural validity | Internal consistency | Crosscultural validity Measurement invariance |

Reliability | Measurement error | Criterion validity | Hypothesis testing for content validity |

Responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kliewer Neumann, et al. (2018) – DAI | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? | + | ? |

| Kliewer Neumann, et al. (2015) – DAI | ? | + | - | ? | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Smyke et al. (2002) - DAI | ? | + | ? | + | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Elovainio et al. (2015) - DAI | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Seim et al. (2019) - PAPA | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Schröder et al. (2019) - RPQ | + | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? | |

| Lehhmann et al. (2020) – RADA | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Lehmann et al. (2015) - DAWBA | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Kliewer-Neumann, et al. (2018) – RAD | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | ? |

| Minnis et al. (2002) - RAD | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Note: | ||||||||

| ||||||||

3.4. Strength of evidence

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowlby, J. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Psychological Disorders in Childhood. Health Education Journal 1954, 12, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeanah CH, Gleason, MM. Annual Research Review: Attachment disorders in early childhood - clinical presentation, causes, correlates, and treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015, 56, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Main, M. Introduction to the special section on attachment and psychopathology: 2. Overview of the field of attachment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996, 64, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresno, A.; Spencer, R.; Retamal, T. Maltrato infantil y representaciones de apego: defensas, memoria y estrategias, una revisión. Universitas Psychologica 2012, 11, 829–838. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, E. E.; Yilanli, M.;Saadabadi, A. Reactive Attachment Disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, 2023.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders(5-TR ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2022.

- Moran K, Dyas R, Kelly C; et al. Reactive Attachment Disorder, Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder, adverse childhood experiences, and mental health in an imprisoned young offender population. Psychiatry Research 2023, 115597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, S; Breivik, K; Monette, S; Minnis, H. Potentially traumatic events in foster youth, and association with DSM-5 trauma- and stressor related symptoms. Child Abuse Negl 2020, 101, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M; Beckwith, H; Duschinsky, R; Forslund, T; Foster, SL.; Coughlan, B.; Pal, S.; Schuengel, C. Attachment difficulties and disorders. InnovAiT 2019, 12, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, 1994.

- Jorjadze N, Bovenschen I, Spangler G. Attachment Representations, and Symptoms of Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder in Foster Children With Different Preplacement Experiences. Devel child welf 2023, 5, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberstein, K. Clarifying core characteristics of attachment disorders. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2006, 76, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, MM.; Fox, NA.; Drury, S.; Smyke, A.; Egger, HL.; Nelson, CA.; Gregas, MC.; Zeanah, CH. Validity of evidence-derived criteria for Reactive Attachment Disorder: Indiscriminately Social/Disinhibited and Emotionally Withdrawn/Inhibited types. J Am Aca Child Adol Psychiatry 2011, 50, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S.; Breivik, K.; Heiervang, ER.; Havik, T.; Havik, OE. Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder in school-aged foster children - a confirmatory approach to dimensional measures. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2016, 44, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberstein, K. One piece of the puzzle: Treatment of fostered and adopted children with RAD and DSED. Adoption & Fostering 2023, 47, 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, C.; Green, J.; Sharma, K. Disinhibited Attachment Disorder in UK adopted children during middle childhood: Prevalence, validity and possible developmental rigin. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2016, 44, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan B, Woolgar M, Van Ijzendoorn M.H, Duschinsky R. Socioemotional profiles of autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and disinhibited and reactive attachment disorders: A symptom comparison and network approach. Development and psychopathology 2023, 35, 1026-1035. [CrossRef]

- Kroupina MG, Dahl C.M, Nakitende AJ, Elison KC. Reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED) symptomatology in a high-risk clinical sample. Clinical pediatrics 2023, 62, 760-768. [CrossRef]

- Muzi S, Pace CS. Attachment and alexithymia predict emotional–behavioural problems of institutionalized, late-adopted and community adolescents: An explorative multi-informant mixed-method study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J; Glinn, L; Osborne, LA; Reed, P. Exploratory study of parenting differences for autism spectrum disorder and attachment disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2023, 53, 2143–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira PS, Fearon P, Belsky J; et al. Neural correlates of face familiarity in institutionalised children and links to attachment disordered behaviour. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 2023, 64, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, MJ.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, PM.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, TC.; Mulrow, CD.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, JM.; Akl, EA.; Brennan, SE.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, CM.; Pimenta, CA.; Nobre, MR. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Latino-am Enfermagem 2007, 15, 508–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. https://www.covidence.org. Accessed 22 Feb 2023.

- Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines From a Detailed Consensus Process. J Nurs Care Qual 2016, 31, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Orwin, R. G. Evaluating coding decisions. In The handbook of research synthesis; Russell Sage Foundation, EEUU, 2018. pp. 95-107.

- Hernández-Nieto, RA. Contributions to Statistical Analysis: The Coefficients of Proportional Variance, Content Validity and Kappa. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2002.

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH. Disturbances of attachment interview. New Orleans: Tulane University; 1999 (Unpublished Manual).

- Angold, A.; Prendergast, M.; Cox, A.; Harrington, R.; Simonoff, E.; Rutter, M. The child and adolescent psychiatric assessment (CAPA). Psychol Med 1995, 25, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnis, H.; Green, J.; O’Connor, T.; Liew, A.; Glaser, D.; Taylor, E.; Follan, M.; Young, D.; Barnes, J.; Gillberg, C.; Pelosi, A.; Arthur, J.; Burston, A.; Connolly, B.; Sadiq, F.A. An exploratory study of the association between reactive attachment disorder and attachment narratives in early school-age children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2009, 50, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S.; Monette, S.; Egger, H.; Breivik, K.; Young, D.; Davidson, C.; Minnis, H. Development and examination of the reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder assessment interview. Assessment 2020, 27, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, R.A.; Körner, A.; Geyer, M.; Pokorny, D. Relationship Patterns Questionnaire (RPQ): Psychometric properties and clinical applications. Psychotherapy Research 2004, 14, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corval, R.; Baptista, J.; Fachada, I.; Soares, I. Rating of inhibited attachment disordered behavior. Unpublished manuscript, Universidade do Minho, 2016.

- Elovainio, M.; Raaska, H.; Sinkkonen, J.; Makipaa, S.; Lapinleimu, H. Associations between attachment-related symptoms and later psychological problems among international adoptees: results from the FinAdo study. Scand J Psychol 2015, 56, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, B.; Woolgar, M.; Van Ijzendoorn, MH.; Duschinsky, R. Socioemotional profiles of autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and disinhibited and reactive attachment disorders: a symptom comparison and network approach. Dev Psychopathol 2021, 35, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giltaij, HP.; Sterkenburg, PS.; Schuengel, C. Psychiatric diagnostic screening of social maladaptive behaviour in children with mild intellectual disability: differentiating disordered attachment and pervasive developmental disorder behaviour. J Intellec Disabil Res 2015, 59, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Moon, DS.; Chang, H.; Lee, SY.; Cho, SW.; Lee, K.; Bahn, GH. Incidence and comorbidity of Reactive Attachment Disorder: Based on national health insurance claims data, 2010–2012 in Korea. Psychiatry Investig 2018, 15, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, FA.; Slator, L.; Skuse, D.; Law, J.; Gillberg, C.; Minnis, H. Social use of language in children with reactive attachment disorder and autism spectrum disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012, 21, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmans, G.; Spilt, J.; Vervoort, E.; Verschueren, K. Inhibited symptoms of Reactive Attachment Disorder: links with working models of significant others and the self. Attach Hum Dev 2019, 21, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M.; Young, D.; Turnbull, S.; Rooksby, M.; Chadwick, G.; Oates, C.; et al. Reactive Attachment Disorder in maltreated young children in foster care. Attach Hum Dev 2019, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.; O’Hare, A.; Mactaggart, F.; Green, J.; Young, D.; Gillberg, C.; et al. Social relationship difficulties in autism and reactive attachment disorder: Improving diagnostic validity through structured assessment. Res Dev Disabil 2015, 40, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon-Harris, KL.; Humphreys, KL.; Fox, NA.; Nelson, CA.; Zeanah, CH. Signs of attachment disorders and social functioning among early adolescents with a history of institutional care. Child Abuse Negl 2019, 88, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, CS.; Oosterman, M.; Schuengel, C.; Bolle, EA.; Boer, F.; Lindauer, RJ. Disturbances in attachment: inhibited and disinhibited symptoms in foster children. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2014, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocovska, E.; Puckering, C.; Follan, M.; Smillie, M.; Gorski, C.; Lidstone, E.; Pritchett, R.; Hockaday, H.; Minnis, H. Neurodevelopmental problems in maltreated children referred with indiscriminate friendliness. Res Dev Disabil 2012, 33, 1560–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, SD.; Calhoun, SL.; Waschbusch, DA.; Breaux, RP.; Baweja, R. Reactive attachment/disinhibited social engagement disorders: Callous-unemotional traits and comorbid disorders. Res Dev Disabil 2017, 63, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, K.; McDonald, J.; Jackson, A.; Turnbull, S.; Minnis, H. A study of Attachment Disorders of young offenders attending specialist services. Child Abuse Negl 2017, 65, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaska, H.; Lapinleimu, H.; Sinkkonen, J.; Salmivalli, C.; Matomäki, J.; Mäkipää, S.; et al. Experiences of School Bullying Among Internationally Adopted Children: Results from the Finnish Adoption (FINADO) Study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2012, 43, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seim, AR.; Jozefiak, T.; Wichstrøm, L.; Lydersen, S.; Kayed, NS. Self-esteem in adolescents with reactive attachment disorder or disinhibited social engagement disorder. Child Abuse Negl 2021, 118, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seim, AR.; Jozefiak, T.; Wichstrøm, L.; Lydersen, S.; Kayed, NS. Reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder in adolescence: co-occurring psychopathology and psychosocial problems. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2022, 31, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Takiguchi, S.; Mizushima, S.; Fujisawa, TX.; Saito, DN.; Kosaka, H.; et al. Reduced visual cortex grey matter volume in children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder. NeuroImage Clinical 2015, 9, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Iwanski, A. Attachment Disorder behavior in early and middle childhood: associations with children's self-concept and observed signs of negative internal working models. Attach Hum Dev 2019, 21, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchett, R.; Pritchett, J.; Marshall, E.; Davidson, C.; Minnis, H. Reactive Attachment Disorder in the general population: A hidden ESSENCE disorder. Scientific World Journal 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, T.; Trost, Z.; Van Ryckeghem, D. M. L. Children’s selective attention to pain and avoidance behaviour: The role of child and parental catastrophizing about pain. Pain 2013, 154, 1979–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, E.; Bosmans, G.; Doumen, S.; Minnis, H.; Verschueren, K. Perceptions of self, significant others, and teacher–child relationships in indiscriminately friendly children. Res Dev Disabil 2014, 35, 2802–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, HL.; Erkanli, A.; Keeler, G.; Potts, E.; Walter, BK.; Angold, A. Test-Retest Reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006, 45, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10: Version 2010. Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva. 2010.

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1992.

- World Health Organisation. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. World Health Organisation, Geneva. 1993.

- Vasquez, M.; Miller, N. Aggression in Children With Reactive Attachment Disorder: A sign of deficits in emotional regulatory processes? J Aggress, Maltreat Trauma 2018, 27, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J. Reactive Attachment Disorder: A biopsychosocial Disturbance of Attachment. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 2007, 24, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, JR.; Schore, AN. Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clin Soc Work J 2008, 36, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questionnaires | Psychometric Properties | Samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disturbance Attachment Interview OR DAI The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment OR PAPA Relationship Patterns Questionnaire OR RPQ Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder Assessment OR RADA Developmental and Well-Being Assessment RAD/DSED OR DAWBA RAD/DSED Questionnaire Disorder Attachment Reactive OR RAD Questionnaire |

AND | validity OR measurement error OR reliability OR invariance OR cross OR retest OR consistence OR responsive |

AND | foster* OR adopt* OR residential foster care |

| Article & Instrument | N | Characteristics of samples |

| Kliewer et al. (2018) – DAI | 55 | Foster children from German youth welfare programs. The children ranged in age from 12 to 82 months (M=35.87; SD=18.37), with 50.9% being female (n=28). These children had been in foster care for an average of 78 days, and some of them had experienced up to 5 changes in placement or families. |

| Kliewer et al. (2015) – DAI | 50 | Foster children aged between 34 and 104 months (M=68.32; SD=19.29), with 48% being female (n=24). The children had been living with their foster families for an average of 45.36 months. |

| Smyke et al. (2002) – DAI | 94 | Children residing in a large institution in Bucharest (n=32), young children residing in the same institution but in a pilot unit (n=29), and young children living in foster care who had never been institutionalized (n=33). All children ranged in age from 4 months to 68 months. |

| Elovainio et al. (2015) - DAI | 853 | Boys and girls adopted as part of a Finnish adoption study (FinAdo), involving international adoption. The participants' ages ranged from 6 to 15 years (M=8.5; SD=2.9), and they had been adopted for an average of 2.4 years (SD=1.3). Prior to adoption, they had experienced various placement resources, including foster care, residential care, among others. An adapted version of the DAI was administered. |

| Seim et al. (2020) - PAPA | 400 | Adolescents aged between 12 and 23 years, residing in Norwegian residential centers. The participants had a mean age of M=16.7 (SD=3.9), an average of 3.3 out-of-home placements (SD=2.4), and the mean age of their first out-of-home placement was 12.5 years (SD=3.9). |

| Schröder et al. (2019) – RPQ | 135 | The sample comprised a total of 135 children, with a mean age of 7.17 years (SD=1.40). The sample divided participants into three groups: general population (n=34), with a mean age of 6.36 years (SD=1.06); hospitalized and outpatient patients (n=69), with a mean age of 7.39 years (SD=1.42); and the foster care group (n=32), with a mean age of 7.52 years (SD=1.42). |

| Lehhmann, Monette et al. (2020) - RADA | 320 | Youth living in foster care for an average of 6.6 years (SD=4.3), aged between 11 and 17 years (M=14.8, SD=2.0), with 56.8% being boys. |

| Lehmann et al. (2015) - DAWBA | 122 | Adopted children aged between 0 and 10 years in Norway, of which 57% were girls. |

| Kliewer et al. (2018) – RAD Questionnaire | 55 | Foster children from German youth welfare programs. The children ranged in age from 12 to 82 months (M=35.87; SD=18.37), with 50.9% being female (n=28). These children had been with their foster families for an average of 78 days, and some of them had experienced up to 5 changes in placement or families. |

| Minnis et al. (2002) – RAD Questionnaire | 182 | Scottish children residing in foster homes aged between five and sixteen years (M=11) and had spent an average of 2.5 years with their current foster caregivers. |

| Psychometric property | Articles | Psychometric property | Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural validity | Measurement error | ||

| Excellent | 4,5,7,8,10 | Excellent | |

| Good | Good | ||

| Fair | Fair | ||

| Poor | Poor | ||

| Unknown/NA | 1,3,10 | Unknown/NA | 1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9,10 |

| Internal consistency | Criterion validity | ||

| Excellent | 2,3,5,6,7,10 | Excellent | 2,4,5,6,7,10 |

| Good | Good | ||

| Fair | Fair | ||

| Poor | Poor | ||

| Unknown/NA | 1,4,8 | Unknown/NA | 1,3,8,11 |

|

Cross-cultural validity/ measurement invariance |

Hypothesis testing for construct validity | ||

| Excellent | Excellent | 1 | |

| Good | Good | 9 | |

| Fair | Fair | ||

| Poor | Poor | ||

| Unknown/NA | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | Unknown/NA | 2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 |

| Reliability | Responsiveness | ||

| Excellent | 1,3,10 | Excellent | |

| Good | Good | ||

| Fair | Fair | ||

| Poor | Poor | ||

| Unknown/NA | 1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 | Unknown/NA | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 |

| Study and Instrument | Structural validity | Internal consistency | Crosscultural validity/ Measurement invariance |

Reliability | Measurement error | Criterion validity | Hypothesis testing for content validity |

Responsi veness |

% strong- moderate evidence |

Average percentage evidence of instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kliewer Neumann, et al. (2018) – DAI | U | U | U | S | U | U | S | U | 25% | 28.13% |

| Kliewer Neumann, et al. (2015) – DAI | U | S | M | U | U | S | U | U | 37.5% | |

| Smyke et al. (2002) - DAI | U | S | U | S | U | U | U | U | 25% | |

| Elovainio et al. (2015) - DAI | S | U | U | U | U | S | U | U | 25% | |

| Seim et al. (2019) - PAPA | S | S | U | U | U | S | U | U | 37.5% | 37.5% |

| Schröder et al. (2019) - RPQ | U | S | U | U | U | S | U | U | 25% | 25% |

| Lehmann, Breivik et al. (2020) – RADA | S | S | U | U | U | S | U | U | 37.5% | 37.5% |

| Lehmann et al. (2015) - DAWBA | S | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | 12.5% | 12.5% |

| Kliewer Neumann, et al. (2018) – RAD | U | U | U | U | U | U | S | U | 12.5% | 18.7% |

| Minnis et al. (2002) - RAD | S | U | U | U | U | S | U | U | 25% | |

| % strong-moderate evidence |

40% | 50% | 0% | 20% | 0% | 60% | 20% | 0% | ||

| % limited conflicting evidence |

0% | 0% | 0% | 80% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| % unknown evidence | 50% | 50% | 90% | 80% | 100% | 40% | 80% | 100% | ||

| ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).