Submitted:

25 December 2023

Posted:

28 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

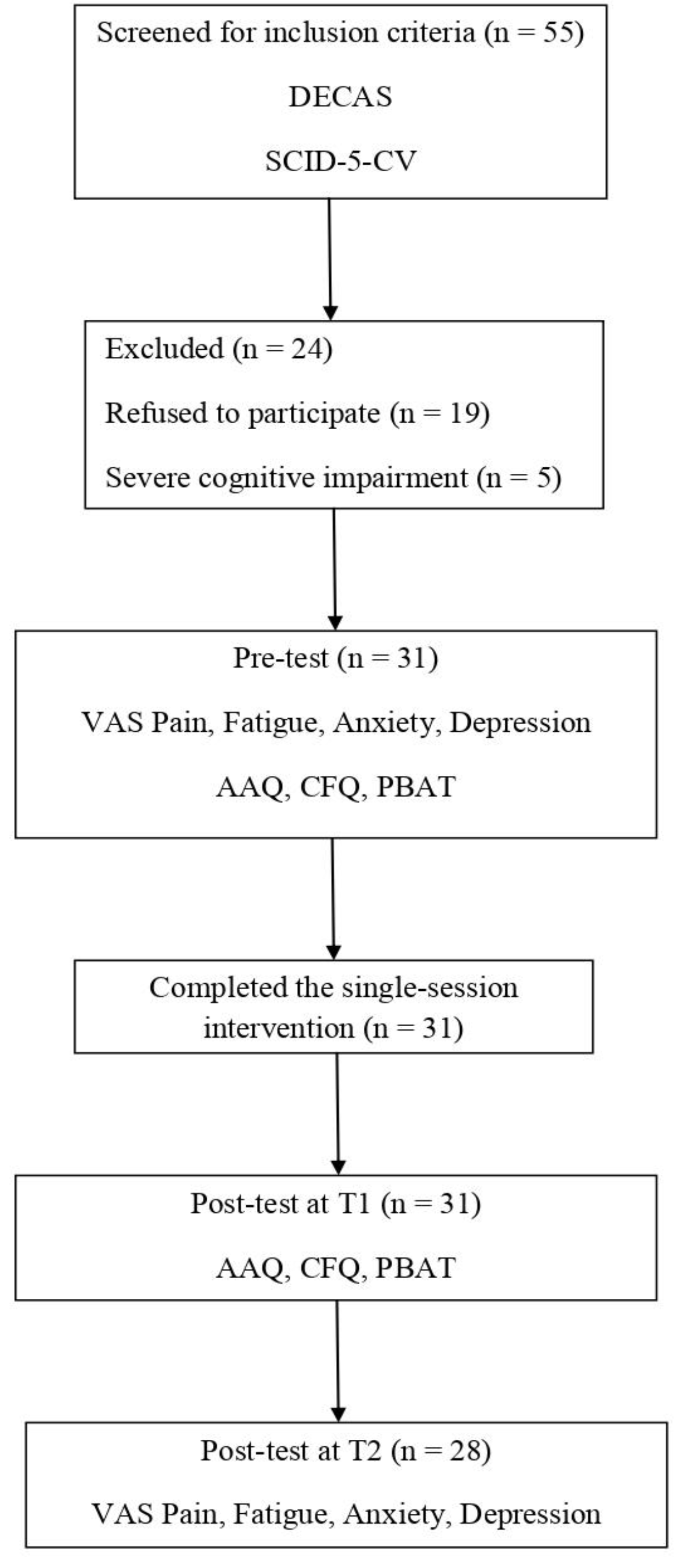

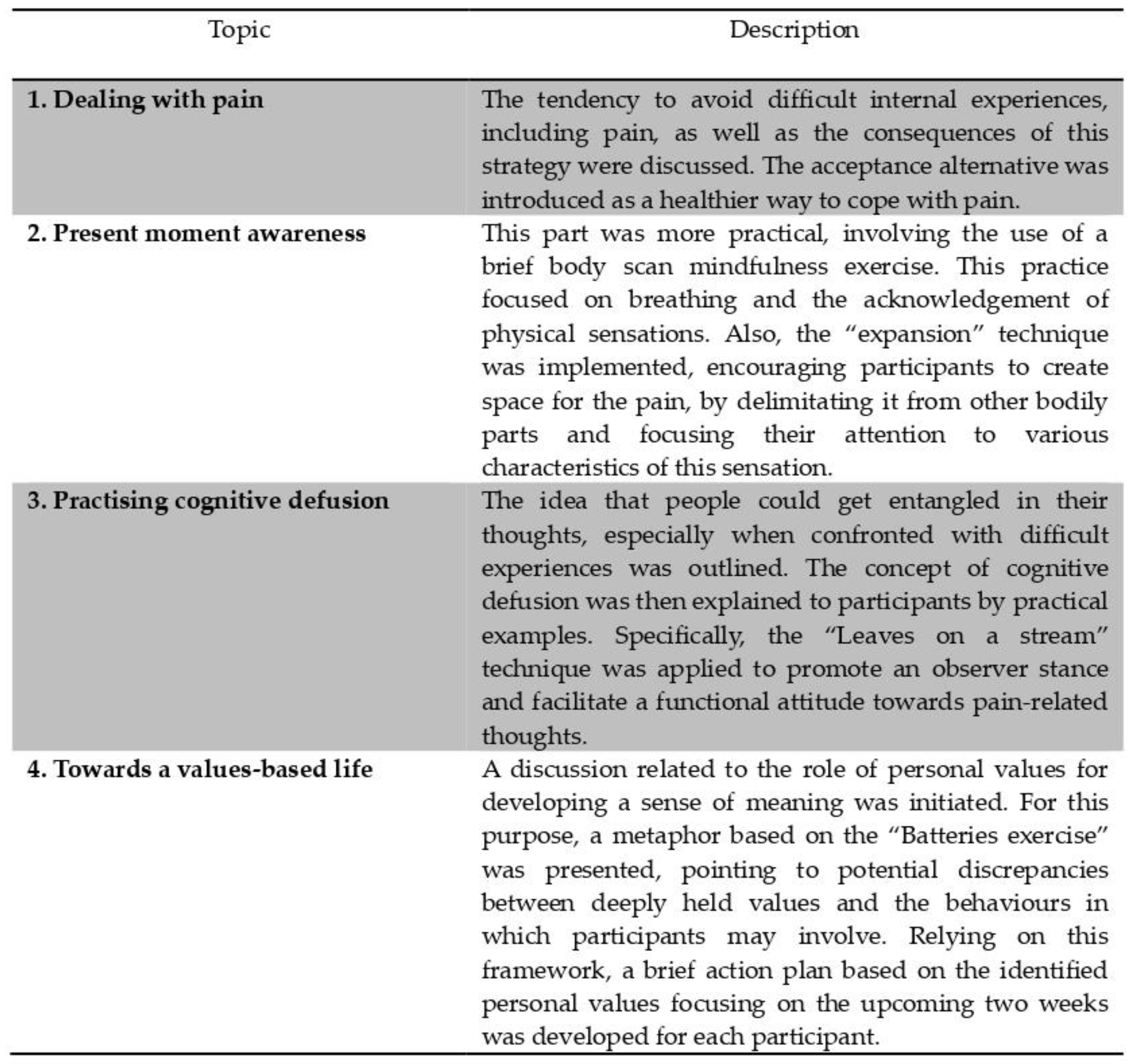

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive characteristics

3.2. Baseline measures

3.3. Intervention outcomes

3.2.1. Results at T1

| Outcome measure | Mean (SD) | t(30) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test T1 | |||

| Cognitive Fusion | 28.19 (17.77) | 17.77 (6.58) | 9.96 | <0.001 |

| Experiential avoidance | 28.06 (6.86) | 19.84 (6.38) | 7.79 | <0.001 |

| Able To Change Behaviour (PBAT_1) | 64.84 (22.19) | 81.61 (20.67) | -4.37 | <0.001 |

| Helped Health (PBAT_6) | 60.00 (24.76) | 79.68 (19.40) | -4.32 | <0.001 |

| Complying (PBAT_9) | 61.61 (27.21) | 41.94 (22.12) | 3.86 | <0.001 |

| Stuck To Working Strategies (PBAT_10) | 45.81 (29.18) | 28.39 (25.04) | 3.27 | 0.003 |

| Hurt Health (PBAT_17) | 45.16 (25.41) | 25.48 (22.03) | 4.05 | <0.001 |

3.2.2. Results at T2

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anyfanti, P.; Gavriilaki, E.; Pyrpasopoulou, A.; Triantafyllou, G.; Triantafyllou, A.; Chatzimichailidou, S.; Gkaliagkousi, E.; Aslanidis, S.; Douma, S. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in a large cohort of patients with rheumatic diseases: common, yet undertreated. Clin Rheumatol 2016, 35, 733–739. [CrossRef]

- Marchi, L.; Marzetti, F.; Orrù, G.; Lemmetti, S.; Miccoli, M.; Ciacchini, R.; Hitchcott, P.K.; Bazzicchi, L.; Gemignani, A.; Conversano, C. Alexithymia and Psychological Distress in Patients With Fibromyalgia and Rheumatic Disease. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 1735. [CrossRef]

- Matcham, F.; Rayner, L.; Steer, S.; Hotopf, M. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and me-ta-analysis. Rheumatology 2013, 52(12), 2136–2148. [CrossRef]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Atzeni, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Perrot, S. The impact of pain on systemic rheumatic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015, 29(1), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [CrossRef]

- Parks, C.G.; Pettinger, M.; de Roos, A.J.; Tindle, H.A.; Walitt, B.T.; Howard, B.V. Life Events, Caregiving, and Risk of Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arthritis Care Res 2023, 75(12), 2519-2528. [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Boelle, P.Y.; Turbelin, C.; Costantino, F.; Kerneis, S.; Said Nahal, R.; Breban, M.; Hanslik, T. Abrupt and unexpected stressful life events are followed with increased disease activity in spondyloarthritis: A two years web-based cohort study. Joint Bone Spine 2019, 86(2), 203–209. [CrossRef]

- Adnine, A.; Nadiri, K.; Soussan, I.; Coulibaly, S.; Berrada, K.; Najdi, A.; Abourazzak, F.E. Mental Health Problems Experienced by Patients with Rheumatic Diseases During COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2021, 17(3), 303–311. [CrossRef]

- Nasui, B.A.; Toth, A.; Popescu, C.A.; Penes, O.N.; Varlas, V.N.; Ungur, R.A.; Ciuciuc, N.; Silaghi, C.A.; Silaghi, H.; Pop, A.L Comparative Study on Nutrition and Lifestyle of Information Technology Workers from Romania before and during COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2022, 14(6), 1202. [CrossRef]

- Nasui, B.A.; Ungur, R.A.; Nasui, G.A.; Popescu, C.A.; Hofer, A.M.; Dersidan, S.; Popa, M.; Silaghi, H.; Silaghi, C.A. Adolescents’ Lifestyle Determinants in Relation to Their Nutritional Status during COVID-19 Pandemic Distance Learning in the North-Western Part of Romania—A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2023, 10, 922. [CrossRef]

- Daïen, C.I.; Tubery, A.; Beurai-Weber, M.; du Cailar, G.; Picot, M.C.; Jaussent, A.; Roubille, F.; Cohen, J.D.; Morel, J.; Bousquet, J.; Fesler, P.; Combe, B. Relevance and feasibility of a systematic screening of multimorbidities in patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Joint Bone Spine 2019, 86(1), 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Golenbiewski, J.T.; Pisetsky, D.S. A Holistic Approach to Pain Management in the Rheumatic Diseases. Curr Treat Options Rheumatol 2019, 5(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, L.; Bathon, J.M.; England, B.R.; St Clair, E.W.; Arayssi, T.; Carandang, K.; Deane, K.D.; Genovese, M.; Huston, K.K.; Kerr, G.; et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2021, 73(7), 924-939. [CrossRef]

- Kolasinski, S.L.; Neogi, T., Hochberg, M.C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; Callahan, L.; Copenhaver, C.; Dodge, C.; Felsonet, D.; al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee [published correction appears in Arthritis Care Res 2021, 73(5), 764]. Arthritis Care Res 2020, 72(2), 149-162. [CrossRef]

- Fashler, S.R.; Cooper, L.K.; Oosenbrug, E.D.; Burns, L.C.; Razavi, S.; Goldberg, L.; Katz, J. Systematic Review of Multidisciplinary Chronic Pain Treatment Facilities. Pain Res Manag 2016, 2016, 5960987. [CrossRef]

- APA Division 12. Psychological treatment of chronic or persistent pain. Society of Clinical Psychology. 2012. Available at: http://www.psychologicaltreatments.org (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Scott, A.J.; Bisby, M.A.; Heriseanu, A.I.; Salameh, Y.; Karin, E.; Fogliati, R.; Dudeney, J.; Gandy, M.; McLellan, L.F.; Wootton, B.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapies for depression and anxiety in people with chronic disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2023, 106, 102353. [CrossRef]

- Geenen, R.; Newman, S.; Bossema, E.R.; Vriezekolk, J.E.; Boelen, P.A. Psychological interventions for patients with rheumatic diseases and anxiety or depression. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012, 26(3), 305–319. [CrossRef]

- Ehde, D.M.; Dillworth, T.M.; Turner, J.A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: Efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol 2014, 69(2), 153–166. [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.C.; Chapman, J.E.; Forman, E.M.; Beck, A.T. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev 2006, 26(1), 17–31. [CrossRef]

- Beard, C.; Millner, A.J.; Forgeard, M.J.; Fried, E.I.; Hsu, K.J.; Treadway, M.T.; Leonard, C.V.; Kertz, S.J.; Björgvinsson, T. Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptom relationships in a psychiatric sample. Psychol Med 2016, 46(16), 3359-3369. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G. Psychotherapeutic Interventions and Processes. Cogn Behav Pract 2022, 29(3), 581–584. [CrossRef]

- Sanford, B.; Ciarrochi, J.; Hofmann, S.; Chin, F.; Gates, K.; Hayes, S. Toward empirical process-based case conceptualization: An idionomic network examination of the process-based assessment tool. J Contextual Behav Sci 2022, 25(4). [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Hofmann, S.G.; Ciarrochi, J. A process-based approach to psychological diagnosis and treatment: The conceptual and treatment utility of an extended evolutionary meta model. Clin Psychol Rev 2020, 82, 101908. [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Dong, J.; Jin, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain on functioning: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021, 131, 59–76. [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, E.; Wileman, V.; Galea Holmes, M.; McCracken, L.M.; Norton, S.; Moss-Morris, R.; Noonan, S.; Barcellona, M.; Critchley, D. Physical Therapy Informed by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (PACT) Versus Usual Care Physical Therapy for Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pain 2020, 21(1-2), 71-81. [CrossRef]

- Malins, S.; Biswas, S.; Rathbone, J., Vogt, W.; Pye, N.; Levene, J.; Moghaddam, N.; Russell, J. Reducing dropout in acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and problem-solving therapy for chronic pain and cancer patients using motivational interviewing. Br J Clin Psychol 2020, 59(3), 424-438. [CrossRef]

- Twohig, M.P.; Levin, M.E. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a Treatment for Anxiety and Depression: A Review. Psy-chiatr Clin North Am 2017, 40(4), 751-770. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.S.; Clark, J.; Colclough, J.A.; Dale, E.; McMillan, D. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Clin J Pain 2017, 33(6), 552-568. [CrossRef]

- Wetherell, J.L.; Afari, N.; Rutledge, T.; Sorrell, J.T.; Stoddard, J.A.; Petkus, A.J.; Solomon, B.C.; Lehman, D.H.; Liu, L.; Lang, A.J.; Atkinson, H.J. A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2011, 152(9), 2098-2107. [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.E.; MacLane, C.; Daflos, S.; Seeley, J.R; Hayes, S.C.; Biglan, A.; Pistorello, J. Examining psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic process across psychological disorders. J Contextual Behav Sci 2014, 3(3), 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press, USA, 2011.

- Popa, C.O.; Rus, A.V.; Lee, W.C.; Cojocaru, C.; Schenk, A.; Văcăraș, V.; Olah, P.; Mureșan, S.; Szasz, S.; Bredicean, C. The Relation between Negative Automatic Thoughts and Psychological Inflexibility in Schizophrenia. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 871. [CrossRef]

- Faustino, B.; Vasco, A.B.; Farinha-Fernandes, A.; Delgado, J. Psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic construct: relationships between cognitive fusion, psychological well-being and symptomatology. Curr Psychol 2023, 42(8), 6056–6061. [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. ACT made simple: An easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy, 2nd ed. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, USA, 2019.

- Larsson, A.; Hooper, N.; Osborne, L.A.; Bennett, P.; McHugh, L. Using brief cognitive restructuring and cognitive defusion tech-niques to cope with negative thoughts. Behav Modif 2016, 40(3), 452–482. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.; Ostafin, B. Experiential avoidance as a functional dimensional approach to psychopathology: An empirical review. J Clin Psychol 2007, 63(9), 871-890. [CrossRef]

- Kratz, A.L.; Ehde, D.M.; Bombardier, C.H.; Kalpakjian, C.Z.; Hanks, R.A. Pain acceptance decouples the momentary associations between pain, pain interference, and physical activity in the daily lives of people with chronic pain and spinal cord injury. J Pain. 2017, 18(3), 319-331. [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.A.; Wren, A.A.; Somers, T.J.; Goetz, M.C.; Fras, A.M.; Huh, B.K.; Rogers, L.L.; Keefe, F.J. Pain acceptance, hope, and optimism: relationships to pain and adjustment in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. J Pain 2011, 12(11), 1155-1162. [CrossRef]

- Branstetter-Rost, A.; Cushing, C.; Douleh, T. Personal values and pain tolerance: Does a values intervention add to acceptance? J Pain. 2009, 10(8), 887-892. [CrossRef]

- Dryden W. Single-Session One-At-A-Time Therapy: A Personal Approach. Aust N Z J Fam Ther 2020, 41, 283-301. [CrossRef]

- Campbell A. Single-Session Approaches to Therapy: Time to Review. Aust N Z J Fam Ther 2012, 33(1), 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Dochat, C.; Wooldridge, J.S.; Herbert, M.S.; Lee, M.W.; Afari, N. Single-Session Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Interventions for Patients with Chronic Health Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Contextual Behav Sci 2021, 20, 52-69. [CrossRef]

- Darnall, B.D.; Roy, A.; Chen, A.L., Ziadni, M.S.; Keane, R.T.; You, D.S.; Slater, K.; Poupore-King, H.; Mackey, I.; Kao, M.C.; et al. Comparison of a Single-Session Pain Management Skills Intervention With a Single-Session Health Education Intervention and 8 Sessions of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial [published correction appears in JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5(4), e229739]. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4(8), e2113401. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Res Methods 2007, 39(2), 175-191. [CrossRef]

- Sava, F. Inventarul de Personalitate DECAS. Timişoara: ArtPress, Romania, 2008.

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J Pers Social Psychol 1987, 52(1), 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Curreri, A.J.; Woodard, L.S. Neuroticism and Disorders of Emotion: A New Synthesis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2021, 30(5), 410–417. [CrossRef]

- Sava, F.A.; Popa, R.I. Personality types based on the Big Five model. A cluster analysis over the Romanian population. Cogn Brain Behav 2011, 15(3), 359-384.

- First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.; Karg, R.S.; Spitzer, R.L. SCID-5-CV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders: Clinician Version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, USA, 2016.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, USA, 2013.

- Shabani, A.; Masoumian, S.; Zamirinejad, S.; Hejri, M.; Pirmorad, T.; Yaghmaeezadeh, H. Psychometric properties of Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders-Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV). Brain Behav 2021, 11(5), e01894. [CrossRef]

- Osório, F.L.; Loureiro, S.R.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Machado-de-Sousa, J.P.; Ushirohira, J.M.; Baes, C.V.W.; Apolinario, T.D.; Donadon, M.F.; Bolsoni, L.M.; Guimarães, T.; et al. Clinical validity and intrarater and test-retest reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 - Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV). Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019, 73(12), 754-760. [CrossRef]

- Jollant, F.; Voegeli, G.; Kordsmeier, N.C.; Carbajal, J.M.; Richard-Devantoy, S.; Turecki, G.; Cáceda, R. A visual analog scale to measure psychological and physical pain: A preliminary validation of the PPP-VAS in two independent samples of depressed patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019, 90, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.; Hoggart, B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 2005, 14(7), 798–804. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe F. Fatigue assessments in rheumatoid arthritis: comparative performance of visual analog scales and longer fatigue questionnaires in 7760 patients. J Rheumatol 2004, 31(10), 1896–1902.

- Huang, Z.; Kohler, I.V.; Kämpfen, F. A Single-Item Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Measure for Assessing Depression Among College Students. Community Ment. Health J 2020, 56(2), 355–367. [CrossRef]

- Williams, V.S.; Morlock, R.J.; Feltner, D. Psychometric evaluation of a visual analog scale for the assessment of anxiety. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 57. [CrossRef]

- Ciarrochi, J.; Sahdra, B.; Hofmann, S.G.; Hayes, S.C. Developing an item pool to assess processes of change in psychological interventions: The Process-Based Assessment Tool (PBAT). J Contextual Behav Sci 2022, 23, 200-213. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Hofmann, S.G.; Ciarrochi, J. A process-based approach to psychological diagnosis and treatment: The conceptual and treatment utility of an extended evolutionary meta model. Clinical Psychol Rev 2020, 82, 101908. [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav Ther 2011, 42, 676–688. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, K.G.; Vargha, J.L.; Balázsi, R.; Bartalus, J.; Bogdan V. Measuring Psychological Flexibility: Preliminary Data on the Psychometric Properties of the Romanian Version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) J Cogn Behav Psychother 2011, 11, 67–82.

- Gillanders, D.; Bolderston, H.; Bond, F.W.; Dempster, M.; Flaxman, P.E.; Campbell, L.; Remington, B. The development and initial validation of the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire. Behav Ther 2014, 45, 83–101. [CrossRef]

- Vowles, K.E.; McCracken, L.M. Acceptance and values-based action in chronic pain: A study of treatment effectiveness and process. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008, 76(3), 397–407. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, J.C.; Lundgren, T.L. Living beyond your pain: Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to ease chronic pain. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, USA, 2006.

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford Press, USA, 1999.

- Sturgeon, J.A.; Finan, P.H.; Zautra, A.J. Affective disturbance in rheumatoid arthritis: psychological and disease-related pathways. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016, 12, 532–542. [CrossRef]

- Usubini, A.G.; Varallo, G.; Giusti, E.M.; Cattivelli, R.; Granese, V.; Consoli, S.; Bastoni, I.; Volpi, C.; Castelnuovo, G. The mediating role of psychological inflexibility in the relationship between anxiety, depression, and emotional eating in adult individuals with obesity. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 861341. [CrossRef]

- Crocker, L.D.; Heller, W.; Warren, S.L.; O'Hare, A.J.; Infantolino, Z.P.; Miller, G.A. Relationships among cognition, emotion, and motivation: implications for intervention and neuroplasticity in psychopathology. Front Hum Neurosci 2013, 11, 7:261. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Haigh, E.A. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2014, 10, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.T.; Chatkoff, D.K.; Maier, K.J. Couples' Relationship Satisfaction and Its Association with Depression and Spouse Responses Within the Context of Chronic Pain Adjustment. Pain Manag Nurs 2019, 19(4), 400-407. [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, S.; Becker, S.; Van der Linden, D. Tired of pain? Toward a better understanding of fatigue in chronic pain. Pain 2018, 159(1), 7-10. [CrossRef]

- Dindo, L.; Zimmerman, M.B.; Hadlandsmyth K, StMarie, B.; Embree, J.; Marchman, J.; Tripp-Reimer, T.; Rakel, B. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Prevention of Chronic Postsurgical Pain and Opioid Use in At-Risk Veterans: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. J Pain 2018, 19(10), 1211-1221. [CrossRef]

- Åkerblom, S.; Perrin, S.; Rivano Fischer, M.; McCracken, L.M. The Mediating Role of Acceptance in Multidisciplinary Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain [published correction appears in J Pain 2016, 17(10), 1135-1136]. J Pain 2015, 16(7), 606-615. [CrossRef]

- Simister, H.D.; Tkachuk, G.A.; Shay, B.L.; Vincent, N.; Pear, J.J.; Skrabek, R.Q. Randomized controlled trial of online acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia. J Pain 2018, 19(7), 741-753. [CrossRef]

- Alda, M.; Luciano, J.V.; Andrés, E.; Serrano-Blanco, A.; Rodero, B.; del Hoyo, Y.L.; Roca, M.; Moreno, S.; Magallón, R.; García-Campayo, J. Effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for the treatment of catastrophisation in patients with fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2011, 13(5), R173. [CrossRef]

- Darnall, B.D.; Sturgeon, J.A.; Kao, M.C.; Hah, J.M.; Mackey, S.C. From catastrophizing to recovery: a pilot study of a single-session treatment for pain catastrophizing. J Pain Res 2014, 7, 219-226. [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, W.P.; Schumann, M.E.; Cunningham, J.L.; Evans, M.M.; Luedtke, C.A.; Morrison, E.J.; Sperry, J.A.; Vowles, K.E. Pain catastrophizing as a treatment process variable in cognitive behavioural therapy for adults with chronic pain. Eur J Pain 2021, 25(2), 339-347. [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A.; Kazemi-Zahrani, H. The Effectiveness of Group Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Pain Intensity, Pain Catastrophizing and Pain-Associated Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Pain. Asian Soc Sci 2015, 11(26). [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; D’Hondt, E.; Clarys, P.; Deliens, T.; Polli, A.; Malfliet, A.; Coppieters, I.; Willaert, W.; Tumkaya Yilmaz, S.; Elma, Ö.; Ickmans, K. Lifestyle and Chronic Pain across the Lifespan: An Inconvenient Truth? PM R 2020, 12(4), 410–419. [CrossRef]

- Znidarsic, J.; Kirksey, K.N.; Dombrowski, S.M.; Tang, A.; Lopez, R.; Blonsky, H.; Todorov, I.; Schneeberger, D.; Doyle, J.; Libertiniet, L.; et al. “Living Well with Chronic Pain”: Integrative Pain Management via Shared Medical Appointments. Pain Med 2021, 22(1), 181–190. [CrossRef]

- Will, K.K.; Johnson, M.L.; Lamb, G. Team-Based Care and Patient Satisfaction in the Hospital Setting: A Systematic Review. J Patient Cent Res Rev 2019, 6(2), 158-171. [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.J.; Holden, M.A.; Foster, N.E.; Jinks C. Therapeutic alliance facilitates adherence to physiotherapy-led exercise and physical activity for older adults with knee pain: a longitudinal qualitative study. J Physiother 2020, 66(1), 45–53. [CrossRef]

- Vowles, K.E.; Sowden, G.; Hickman, J.; Ashworth, J. An analysis of within-treatment change trajectories in valued activity in relation to treatment outcomes following interdisciplinary Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for adults with chronic pain. Behav Res Ther 2019, 115, 46–54. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Vowles, K.E.; Johnson, L.E.; Gertz, K.J. Living Well with Pain: Development and Preliminary Evaluation of the Valued Living Scale. Pain Med 2015, 16(11), 2109–2120. [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L.M.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, O. Processes of change in psychological flexibility in an interdisciplinary group-based treatment for chronic pain based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Behav Res Ther 2011, 49(4), 267–274. [CrossRef]

- Kanzler, K.E.; Robinson, P.J.; McGeary, D.D.; Mintz, J.; Kilpela, L.S.; Finley, E.P.; McGeary, C.; Lopez, E.J.; Velligan, D.; Munante, M.; et al. Addressing chronic pain with Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in integrated primary care: findings from a mixed methods pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Prim Care 2022, 23(1), 77. [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Ng, J.Y.Y.; Prestwich, A.; Quested, E.; Hancox, J.E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Lonsdale, C.; Williams, G.C. A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychol Rev 2021, 15(2), 214–244. [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Wright, C.E.; Avishai, A.; Villegas, M.E.; Rothman, A.J.; Klein, W.M.P. Does increasing autonomous motivation or perceived competence lead to health behavior change? A meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2021, 40(10), 706–716. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.M.; Huck, G.; Iwanaga, K.; Chan, F.; Wu, J.R.; Finnicum, C.A., Brinck, E.A.; Estala-Gutierrez, V.Y.Towards an inte-gration of the health promotion models of self-determination theory and theory of planned behavior among people with chronic pain. Rehabil Psychol 2018, 63(4), 553–62. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, A.; Ascigil, E.; Turunc, G. Spousal autonomy support, need satisfaction, and well-being in individuals with chronic pain: A longitudinal study. J Behav Med 2017, 40(2), 81–92. [CrossRef]

- Vriezekolk, J.E.; Geenen, R.; van den Ende, C.H.M.; Slot, H.; van Lankveld, W.G.J.M.; van Helmond, T. Behavior change, acceptance, and coping flexibility in highly distressed patients with rheumatic diseases: Feasibility of a cognitive-behavioral therapy in multimodal rehabilitation. Patient Educ Couns 2012, 87(2), 171–7. [CrossRef]

- Hajihasani, A.; Rouhani, M.; Salavati, M.; Hedayati, R.; Kahlaee, A.H. The influence of cognitive behavioral therapy on pain, quality of life, and depression in patients receiving physical therapy for chronic low back pain: a systematic review. PM R 2019, 11(2), 167-76. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.W.; Yuen, A.S.; Yang, Z.The efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain 2023, 39(3), 147-57. [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.W.; Jense, M.P.; Thorn, B.; Lillis, T.A.; Carmody, J.; Newman, A.K.; Keefe, F. Cognitive therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and behavior therapy for the treatment of chronic pain: randomized controlled trial. Pain 2022, 163(2), 376-389. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Fernández, M.; López-López, A.; Losada, A.; González, J.L.; Wetherell, J.L. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Selective Optimization with Compensation for Institutionalized Older People with Chronic Pain. Pain Med 2016, 17(2), 264-277. [CrossRef]

- Ólason, M.; Andrason, R.H.; Jónsdóttir, I.H.; Kristbergsdóttir, H.; Jensen, M.P. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in an Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation Program for Chronic Pain: a Randomized Controlled Trial with a 3-Year Fol-low-up. Int J Behav Med 2018, 25(1), 55–66. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.P.; Poulis, N.; Moreton, B.J.; Walsh, D.A.; Lincoln, N.B. Evaluation of a group acceptance commitment therapy intervention for people with knee or hip osteoarthritis: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil 2017, 39(7), 663–670. [CrossRef]

- Trompetter, H.R.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Veehof, M.M; Schreurs, K.M. Internet-based guided self-help intervention for chronic pain based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med 2015, 38, 66-80. [CrossRef]

- Luciano, J.V.; Guallar, J.A.; Aguado, J.; López-Del-Hoyo,Y.; Olivan, B.; Magallón, R.; Alda, M.; Serrano-Blanco, A.; Gili, M.; Garcia-Campayo, J. Effectiveness of group acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: a 6-month randomized con-trolled trial (EFFIGACT study). Pain 2013, 155(4), 693–702. [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Benoist, M.; Bout, Z.; Karels, E.; Smit A. Effect of a Cognitive Behavioral Self-Help Intervention on Depression, Anxiety, and Coping Self-Efficacy in People With Rheumatic Disease. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013, 65(7), 1077–84. [CrossRef]

- Joypaul, S.; Kelly, F.S.; King, M.A. Turning pain into gain: evaluation of a multidisciplinary chronic pain management pro-gram in primary care. Pain Med. 2019, 20(5), 925-33. [CrossRef]

- Casey, M.; Smart, K.; Segurado, R.; Doody C. Multidisciplinary-based Rehabilitation (MBR) Compared With Active Physical Interventions for Pain and Disability in Adults With Chronic Pain A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin J Pain 2020, 36(11), 874–86. [CrossRef]

- Fashler, S.R.; Cooper, L.K.; Oosenbrug, E.D.; Burns, L.C.; Razavi, S.; Goldberg, L.; Katz, J. Systematic Review of Multidisci-plinary Chronic Pain Treatment Facilities. Pain Res Manag 2016, 2016, 5960987. [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.A.; IsHak, W.W.; Dang, J., Vanle, B.; Mahtani, N.; Danovitch, I. Psychological interventions in inpatient medical settings: A brief review. Int J Healthc Med Sci 2018, 4, 73-83.

- Davis, J.P.; Prindle, J.J.; Eddie, D.; Pedersen, E.R.; Dumas, T.M.; Christie, N.C. Addressing the opioid epidemic with be-havioral interventions for adolescents and young adults: A quasi-experimental design. J Consult Clin Psychol 2019, 87(10), 941–951. [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulou, E.; Efthymiou, D.; Papatriantafyllou, E.; Markopoulou, M.; Sakellariou, E.M.; Popescu, A.C. Long Term Metabolic and Inflammatory Effects of Second-Generation Antipsychotics: A Study in Mentally Disordered Offenders. J Pers Med 2021, 11(11), 1189. [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferri, S.D.; Miller, C.T.; Owen, P.J.; Mitchell, U.H.; Brisby, H.; Fitzgibbon, B.; Masse-Alarie, H.; Van Oosterwijck, J.; Belavy D.L. Domains of chronic low back pain and assessing treatment effectiveness: a clinical perspective. Pain Pract 2020, 20(2), 211-25. [CrossRef]

- Jack, K.; McLean, S.M.; Moffett, J.K.; Gardiner E. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a sys-tematic review. Man Ther 2010, 15, 220–228. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, J.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y.; Lin, X.; Hall, J., Xu, H.; Xu, J.; Xu, X. The effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on depression, anxiety, and stress in patients with COVID-19: a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 580827. [CrossRef]

| Age (M, SD) | 58.9 (12.03) |

| Gender (N,%) | |

| Female | 29 (94) |

| Male | 2 (6) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 25 (81) |

| Single | 1 (3) |

| Widowed | 5 (16) |

| Occupational status | |

| Employed | 4 (13) |

| Unemployed | 8 (26) |

| Retired | 19 (61) |

| Main diagnosis | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 1 (3) |

| Chronic post-surgical pain | 2 (7) |

| Coxarthrosis/ Gonarthrosis | 2 (7) |

| Osteoarthritis | 9 (29) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1 (3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 10 (32) |

| Spondylosis (cervical/ lumbar)Psychodiagnosis | 6 (19) |

| GAD1 | 16 |

| MDD2 | 3 |

| GAD1 + MDD2 | 12 |

| Pain intensity (M, SD) | 8.12 (1.78) |

| Fatigue | 8.09 (2) |

| State_Anxiety | 6.54 (2.89) |

| State_Depression | 6.35 (2.52) |

| Dimension | Pain | Fatigue | Anxiety | Depression | Experiential Avoidance | Cognitive Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurt Connect | .40* | -.07 | .07 | -.04 | .24 | .31 |

| Experience Range Emotions | -.31 | .06 | -.17 | -.17 | -.39* | -.36* |

| Thinking Got In Way | .22 | .09 | .42* | .13 | .33 | .30 |

| Important Challenge | -.08 | .49** | .01 | .23 | -.10 | -.10 |

| Stuck Unable Change | -.08 | -.37* | -.08 | -.21 | -.11 | -.10 |

| Thinking Helped Life | -.29 | .18 | -.13 | .04 | -.41* | -.35* |

| Struggle Connect Moments | -.23 | .27 | -.20 | -.06 | -.35* | -.30 |

| Connect To People | -.12 | .41* | -.10 | -.06 | -.29 | -.33 |

| Personal Impor | -.09 | .41* | -.09 | .13 | -.22 | -.16 |

| Hurt Health | .17 | -.01 | .11 | .11 | .45** | .60** |

| Pain | - | .34 | .40* | .24 | .29 | .43* |

| Fatigue | - | .23 | .41* | .07 | .02 | |

| State Anxiety | - | .14 | .37* | .28 | ||

| State Depression | - | .16 | .18 | |||

| Experiential Avoidance | - | .60** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).