Submitted:

26 December 2023

Posted:

26 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meineke, E. K., Davis, C. C., & Davies, T. J. The unrealized potential of herbaria in global change biology. Ecological Monographs. 2018. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a9ff80c5417fc256c80033e/t/5b157d34f950b782f2709844/1528134965344/Meineke_et_al-2018-Ecological_Monographs.pdf.

- Wheeler Q.D., Knapp S., Stevenson D.W. Mapping the biosphere: exploring species to understand the origin, organization and sustainability of biodiversity. Systematics and Biodiversity. 2012. 10, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Thiers, B. The World’s Herbaria 2021: A Summary Report Based on Data from Index Herbariorum. 2021. 6, published February 2022. http:// sweetgum.nybg.org/science/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/The_Worlds_ Herbaria_Jan_2022.pdf.

- Heberling, J.M. Herbaria as Big Data Sources of Plant Traits. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2022. 183, 87–118. [CrossRef]

- Gasper, A. L. de, Stehmann, J. R., Roque, N., Narcísio, C. B., Sartori, Â. L. B., & Grittz, G. S. Brazilian herbaria: An overview. Acta Botanica Brasilica. 2020. 34(2), 352–359. [CrossRef]

- Stefanaki A., Porck H., Grimaldi I.M., Thurn N., Pugliano V., Kardinaal A. Breaking the silence of the 500-year-old smiling garden of everlasting flowers: The En Tibi book herbarium. PLoS ONE. 2019. 14(6): e0217779. [CrossRef]

- Funk V.A. Collections-based science in the 21st Century. J. Syst. Evol. 2018. 56, 175–193. 10.1111/jse.12315.

- Nelson, G., Ellis, S.The history and impact of digitization and digital data mobilization on biodiversity research. Philosophical Transactions Royal Society. 2018. B 374: 20170391. [CrossRef]

- Park D.S,. Xie Y., Ellison A.M., Lyra G.M., & Davis C.C. Complex climate-mediated effects of urbanization on plant reproductive phenology and frost risk. New Phytologist .2023. 239: 2153–2165.

- Nualart, N., Ibáñez, N., Soriano, I. Assessing the Relevance of Herbarium Collections as Tools for Conservation Biology. Bot. Rev. 2017. 83, 303–325. [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. D., Zimmer, E. A., Olsen, M. T., Foote, A. D., Gilbert, M. T. P., & Brush, G. S. Herbarium specimens reveal a historical shift in phylogeographic structure of common ragweed during native range disturbance. Molecular Ecology. 2014. 23(7), 1701–1716. https://doi. org/10.1111/mec.12675.

- Beck, J. B., & J. C. Semple. Data from: Next-generation sampling: Pairing genomics with herbarium specimens provides species-level signal in Solidago (Asteraceae). 2015. Dryad Digital Repository, http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.16pj5.

- Lavoie, C. Biological collections in an ever changing world: Herbaria as tools for biogeographical and environmental studies. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 2013. 15(1): 68–76. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, R.C., & Andrino, C. Herbário UB: 60 anos de história. 1 ed.; Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, 2023. 201p.

- JBRJ. 2023. Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Jabot - Banco de Dados da Flora Brasileira. Disponível em: [http://jabot.jbrj.gov.br/]. Acesso em 20/12/2023.

- INSTITUTO DE BOTÂNICA-SP. Projeto do Instituto de Botânica sobre briófitas. Estudo do IBT sobre as briófitas nas áreas das Formações Pioneiras. 2015. Disponível em: https://www.infraestruturameioambiente.sp.gov.br/institutodebotanica/2015/09/projeto-do-instituto-de-botanica-sobre-briofitas.

- Carvalho Silva, M. & Câmara, P.E.A.S. O herbário de briófitas da Universidade de Brasília. In Herbário UB: 60 anos de história.; 1 ed.; De Oliveira, R.C., & Andrino, C. Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, 2023; pp. 172-176.

- Cavalvante T.B. & Amaral-Lopes A.C. Flora do Distrito Federal, Brasil. 2017. First edition. Embrapa, Brasília.

- Thiers B. 2021. (continuously updated) Index Herbariorum: A global directory of public herbaria and associated staff. 2021. New York Botanical Garden’s Virtual Herbarium. http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/.

- IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Manual técnico da vegetação brasileira: sistema fitogeográfico : inventário das formações florestais e campestres : técnicas e manejo de coleções botânicas : procedimentos para mapeamentos. Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. 2012. 272p.

- Fiaschi, P., & Pirani, J.R. Review of plant biogeographic studies in Brazil. Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 2009. 47: 477-496. [CrossRef]

- QGIS.org. - Geographic Information System. Open-Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2023. http://qgis.org”.

- CNCFlora - Centro Nacional de Conservação da Flora. Lista Vermelha da flora brasileira versão 2012.2. 2012. Disponível em < http://cncflora.jbrj.gov.br/portal >.

- Bischler-Causse, H., Gradstein, S.R., Jovet-Ast, S., Long, D.G. & Allen, N.S. Marchantiidae. Flora Neotropica Monograph .2005. 97: 1-262.

- Flora e Funga do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. 2023. Disponível em: < http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/ >. Acesso em: 23 Dez 2023.

- Delgadillo-Moya, C., Ecolástico, D.A., Herrera-Panigua, E., Peña-Retis, P., Juárez-Martínez, C. 2022. Manual de Briófitas. ed. 3. Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. pp. 1-163.

- Correia, R.P., Nascimento, J.A., Batista, J.P.S., Silva, M.P.P., Valente, E.B. 2015. Composição e aspectos de comunidades de briófitas da região da Chapada Diamantina, Brasil. Pesquisas Botânica 67: 243-254.

- Gradstein, S.R, Churchill, S.P., & Salazar, A.N. Guide to the Bryophytes of Tropical America. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden. 2001. 86, 577 p.

- Vanderpoorten, A. & Goffinet, B. Introduction to Bryophytes. 2009. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

- Gradstein, S.R. & Pocs, T. 1989. Bryophytes. in: Lieth, H. & Werger, M.J.H. Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystems .2009. Elsevies Science Publishers B. V. pp. 311-325.

- Canestraro, B.K. & Peralta, D. F. Sinopse do gênero Brachymenium Schwägr. (Bryaceae) no Brasil. Hoehnea 2022. 49: e752021.

- Amélio, L. De Almeida, Peralta, D.F. The genus Notothylas (Notothyladaceae, Anthocerotophyta) in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Botany. 2020. v. 44, pp. 1-10.

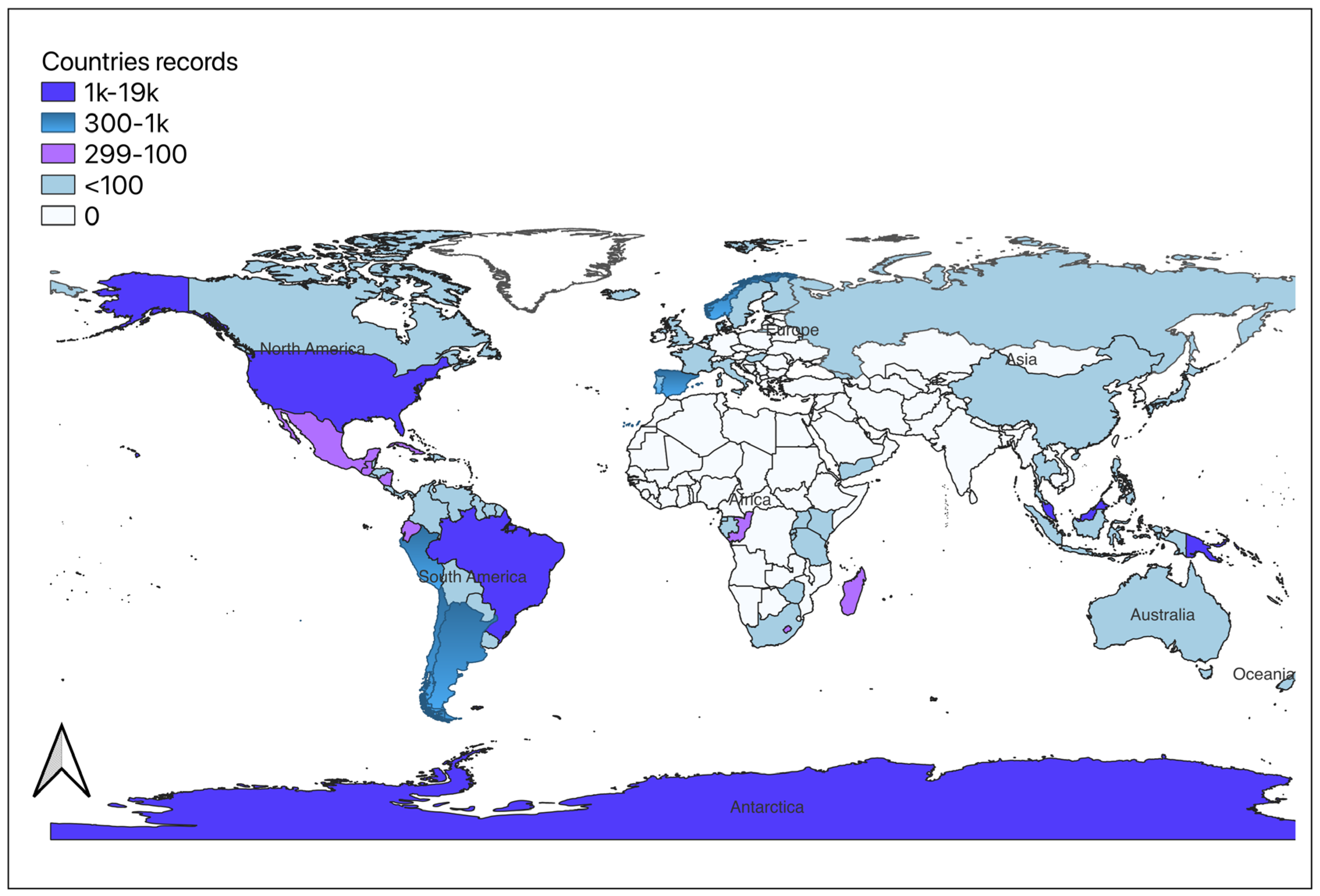

| Continents | Records |

|---|---|

| South America | 14,081 |

| Antarctica | 5,871 |

| Asia | 1,298 |

| Oceania | 1,032 |

| Africa | 502 |

| North America | 454 |

| Europe | 381 |

| Country | Records |

|---|---|

|

19,553 |

|

1,032 |

|

791 |

|

710 |

|

577 |

|

565 |

|

108 |

|

107 |

|

50 |

|

40 |

| Country | Records |

|---|---|

|

1,011 |

|

743 |

|

674 |

|

601 |

|

558 |

| Collectors | Records |

|---|---|

|

3,866 |

|

2,079 |

|

1,616 |

|

1,204 |

|

934 |

|

837 |

|

827 |

|

687 |

|

523 |

|

338 |

| Determiners | Records |

|---|---|

| 1. CÂMARA, PEAS | 3,332 |

| 2. PERALTA, DF | 2,074 |

| 3. SOUSA, RV | 1,342 |

| 4. FARIA, ALA | 820 |

| 5. SOARES, AER | 740 |

| 6. EVANGELISTA, M | 483 |

| 7. CUNHA, MJ | 389 |

| 8. SOUZA, RV | 149 |

| 9. CARVALHO-SILVA, M | 109 |

| 10. STEERE, WC | 80 |

| Species | Collector | Collection date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bracrythecium plumosum Hedw.) Schimp. | Pringle, CG 394. | 2-X-1880 | USA, Vermont Brooks |

| Ptilium crista-castrensis (Hedw.) De Not. | Pringle, CG s.n. | 2-X-1880 | USA, Vermont Underwill |

| Thuidium subserratum Renauld & Cordot | Humblot, L s.n. | 1890 | Monaco |

| Haplocladium riograndense Mull. Hal. | Ule, E 96 | 1890 | Brazil, Santa Catarina |

| Braunia andrieuxii Lorentz | Pringle, CG 742 | 09-XI-1890 | México, Michocoan |

| Rhaphidorrhynchium cyparissoides (Hornsch.) Broth. | Ule, E 64 | VI-1890 | Brazil, Santa Catarina Serra Geral |

| Jungermannia grandiretis Lindb. | Tolf, R 34 | 13-VI-1890 | Sweden Östergötland |

| Mnium intermedium Kindb. | Holzinger, JM s.n. | V-1890 | USA, Bear Creek Minessota |

| Jungermannia guttulata Lindb. & Arnell | Arnell, HW 34 Gestri; | 04-VIII-1900 | Sweden |

| Thuidium liliputanum Broth | Watts, WW s.n | V-1900 | Australia New South Wales |

| Acroporium pungens (Hedw.) | Britton, NL 703 | 08-IX-1901 | Saint Kitts Nevi St. Kitts |

| Thuidium schistocalyx (Mull. Hal. Mitt) | Ule, E 282 | VII-1901 | Brazil, Jurua |

| Thuidium subdelicatulum Hampe & Broth | Schiffner 479 | 12-IX-1901 | Brazil, Rio de Janeiro |

| Polytrichastrum alpinum G.L. Smith | Peary, RE 13 | 1902 | Fort Conger, Greenland |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).