Submitted:

26 December 2023

Posted:

26 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

2.3. Analysis of Data

3. Results

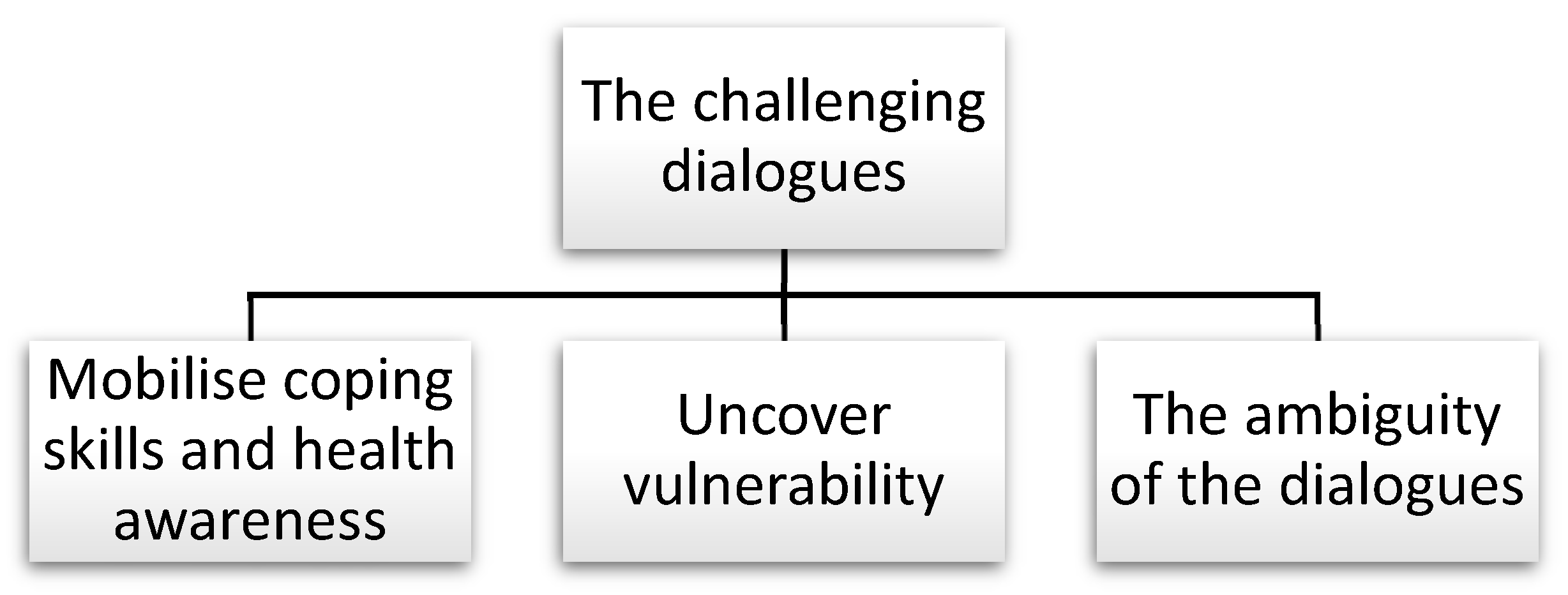

3.1. Theme: The Challenging Dialogues

3.1.1. Sub-Theme 1: Mobilise Coping Skills and Health Awareness

3.1.2. Subtheme 2: UNCOVER VULNERABILITY

3.1.3. Sub-Theme 3: The Ambiguity of the Dialogue

4. Discussion

4.1. The Health-Promotion Opportunity Space

4.2. The Health-Promotion Mandate

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statements

References

- Ministry of Health and Care. Meld. St. 24 (2022–2023) Community and Mastery — Live safely at home. Oslo: The Ministries’ Security and Service Organisation; 2023.

- Thomas MJ, Tømmerås AM. Norways´s 2022 national population projections. Results, methods and assumptions.. Statistics Norway (SSB); 2022. Contract No.: 2022/28.

- Ministry of Health and Care. Meld. St. (2017-2018) A full life - A your life - A Quality Reform for Older People. Oslo: The Ministries’ Security and Service Organisation; 2018.

- Ministry of Finance. Meld.St.29 (2016-2017) Long-term Perspectives on the Norwegian Economy 2017. Oslo: The Ministries’ Security and Service Organisation; 2017. p. 228.

- Haugan G, Rannestad T. Helsefremming i kommunehelsetjenesten. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk; 2014.

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. Styringsinformasjon til helsefellesskapene. Del 1: Skrøpelige eldre og personer med flere kroniske sykdommer. 2021. Report No.: IS-2997.

- Pani-Harreman KE, Bours GJJW, Zander I, Kempen GIJM, van Duren JMA. Definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’: a scoping review. Ageing Soc. 2021;41(9):2026-59. [CrossRef]

- Helgesen MK, Herlofsen K. Kommunenes planlegging og tiltak for en aldrende befolkning. Oslo: By- og regionforskningsinstituttet NIBR; 2017. Report No.: 2017:16.

- Johnsen HC, Evensen AE, Brataas HV. Forebyggende hjemmebesøk til eldre. Fokus på mestring, mening og trivsel i hverdagen. In: Hedlund M, Ingstad K, Moe A, editors. God helse Kunnskap for framtidens kommunehelsetjeneste. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2021. p. 115-33.

- Ministry of Health and Care. Report No. 47 to the Storting (2008-2009) The Coordination Reform — Proper treatment – at the right place and right time. Oslo: The Ministries’ Security and Service Organisation; 2009.

- Ministry of Health and Care. Public Health Act; 2012.

- Skumsnes R, Teigen S, Alvsvåg H, Førland O. Forebyggende hjemmebesøk til eldre. Idehåndbok med anbefalinger.: Senter for Omsorgsforskning Vest; 2015.

- Markle-Reid M, Browne G, Weir R, Gafni A, Roberts J, Henderson SR. The Effectiveness and Efficiency of Home-Based Nursing Health Promotion for Older People: A Review of the Literature. Medical Care Research and Review. 2006;63(5):531-69. [CrossRef]

- Dale B, Westbye B. Forebyggende og helsefremmende hjemmebesøk til eldre på Agder. En oversikt over karakteristika og sammenhenger og endringer ved oppfølgingsbesøk. Senter for omsorgsforskning Sør; 2021. Report No.: 2.

- Førland O, Skumsnes R. Forebyggende og helsefremmende hjemmebesøk til eldre. Senter for omsorgsforskning Vest; 2017.

- Skovdahl K, Blindheim K, Alnes RE. Forebyggende hjemmebesøk til eldre – erfaringer og utfordringer. Tidsskrift for omsorgsforskning. 2015;1(1):62-71. [CrossRef]

- World health Organization, Health and Welfare Canada, Canadian Public Health Association. OTTAWA CHARTER FOR HEALTH PROMOTION. Canadian Journal of Public Health 1986;77(6).

- Evans R, Atim A. HIV care and interdependence in Tanzania and Uganda. In: Barnes M, Brannelly T, Ward L, Ward N, Evans R, Atim A, editors. Ethics of Care: Critical advances in international perspective. Policy Press; 2015. p. 151-64.

- Lerdal A, Fagermoen MS. Læring og mestring - et helsefremmende perspektiv i praksis og forskning. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2011.

- Askheim, OP. Empowerment i helse- og sosialfaglig arbeid. Floskel, styringsverktøy eller frigjøringsstrategi? Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2012.

- Hansen R, Solem M-B. Sosialt arbeid. En situert praksis. Oslo: Gyldedal Akademisk; 2017.

- Tveiten, S. Helsepedagogikk. Helsekompetanse og brukermedvirkning. Oslo: Fagbokforlaget; 2020.

- Spence Laschinger HK, Gilbert S, Smith LM, Leslie K. Towards a comprehensive theory of nurse/patient empowerment: applying Kanter’s empowerment theory to patient care. J Nurs Manage. 2010;18(1):4-13. [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen K, Dihle A, Hansen C, Nordhaug M, Jerpseth H, Tveiten S, et al. Empowerment in healthcare: A thematic synthesis and critical discussion of concept analyses of empowerment. Patient Education and Counseling. 2020;103(7):1263-71. [CrossRef]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups. A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4 ed: Sage Publications Inc.; 2009.

- Halkier, B. Fokusgrupper. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2010.

- Thagaard, T. Systematikk og innlevelse. En innføring i kvalitative metoder. 5 ed. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2018.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101. [CrossRef]

- Clarke V, Braun V. Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: A critical reflection. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2018;18(2):107-10. [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2019;11(4):589-97. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Care. Care Plan 2020. Oslo: The Ministries’ Security and Service Organisation; 2015.

- Tøien M, Bjørk IT, Fagerström L. An exploration of factors associated with older persons’ perceptions of the benefits of and satisfaction with a preventive home visit service. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018;32(3):1093-107. [CrossRef]

- Tøien M, Bjørk IT, Fagerström L. ‘A longitudinal room of possibilities’ – perspectives on the benefits of long-term preventive home visits: A qualitative study of nurses’ experiences. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research. 2020;40(1):6-14. [CrossRef]

- Vass M, Avlund K, Hendriksen C, Philipson L, Riis P. Preventive home visits to older people in Denmark. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;40(4):209-16.

- Marcus-Varwijk AE, Madjdian DS, de Vet E, Mensen MWM, Visscher TLS, Ranchor AV, et al. Experiences and views of older people on their participation in a nurse-led health promotion intervention: “Community Health Consultation Offices for Seniors”. Plos One. 2019;14(5):e0216494. [CrossRef]

- Tøien M, Heggelund M, Fagerström L. How Do Older Persons Understand the Purpose and Relevance of Preventive Home Visits? A Study of Experiences after a First Visit. Nursing Research and Practice. 2014;2014:640583. [CrossRef]

- Lagerin A, Törnkvist L, Hylander I. District nurses’ experiences of preventive home visits to 75-year-olds in Stockholm: a qualitative study. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2016;17(5):464-78. [CrossRef]

- Behm L, Ivanoff SD, Zidén L. Preventive home visits and health – experiences among very old people. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):378. [CrossRef]

- Golinowska S, Groot W, Baji P, Pavlova M. Health promotion targeting older people. BMC Health Services Research. 2016;16(5):345.

- Korkmaz Aslan G, Kartal A, Özen Çınar İ, Koştu N. The relationship between attitudes toward aging and health-promoting behaviours in older adults. Int J Nurs Pract. 2017;23(6):e12594. [CrossRef]

- Gough A, Cassidy B, Rabheru K, Conn D, Canales DD, Cassidy K-L. The Fountain of Health: effective health promotion knowledge transfer in individual primary care and group community-based formats. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(2):173-80. [CrossRef]

- Lima KC, Caldas CP, Veras RP, Correa RdF, Bonfada D, de Souza DB, et al. Health Promotion and Education:A Study of the Effectiveness of Programs Focusing on the Aging Process. International Journal of Health Services. 2017;47(3):550-70. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing. A policy Framework. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

- Blix BH, Agotnes G. Aging Successfully in the Changing Norwegian Welfare State: A Policy Analysis Framed by Critical Gerontology. Gerontologist. 2023;63(7):1228-37. [CrossRef]

- Johnson KJ, Mutchler JE. The Emergence of a Positive Gerontology: From Disengagement to Social Involvement. The Gerontologist. 2013;54(1):93-100. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).