Submitted:

13 December 2023

Posted:

27 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

2. The Chinese Legal Framework of Regulating Artificial Intelligence

2.1. Why Artificial Intelligence Need to be Regulated

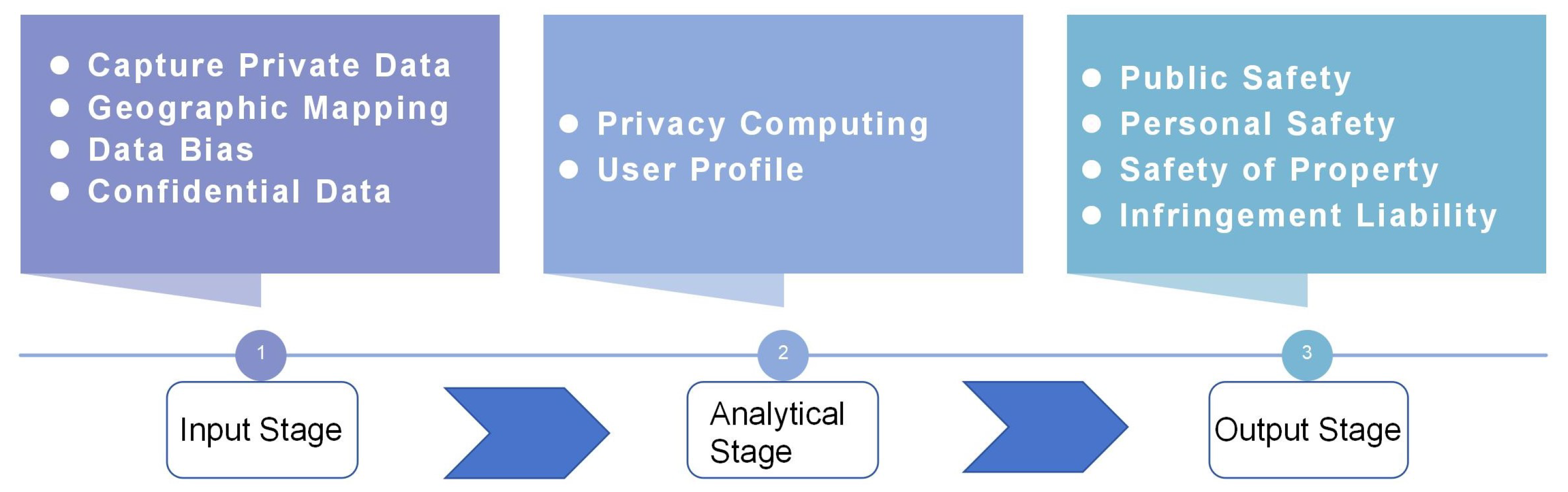

2.1.1. Challenges to Security

2.1.2. Challenges to the protection of intellectual property

2.2. How China Regulates Artificial Intelligence

2.2.1. Differentiated Regulation Based on the Size of the AI Company

2.2.2. Establishing a Regulatory Framework with the Participation of Multiple Subjects

2.2.3. Decentralized Regulatory Norms Based on Differential Industry Application Scenarios

3. Regulatory Rationality in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: a Cost-Benefit Analysis in the Framework of Cooperation

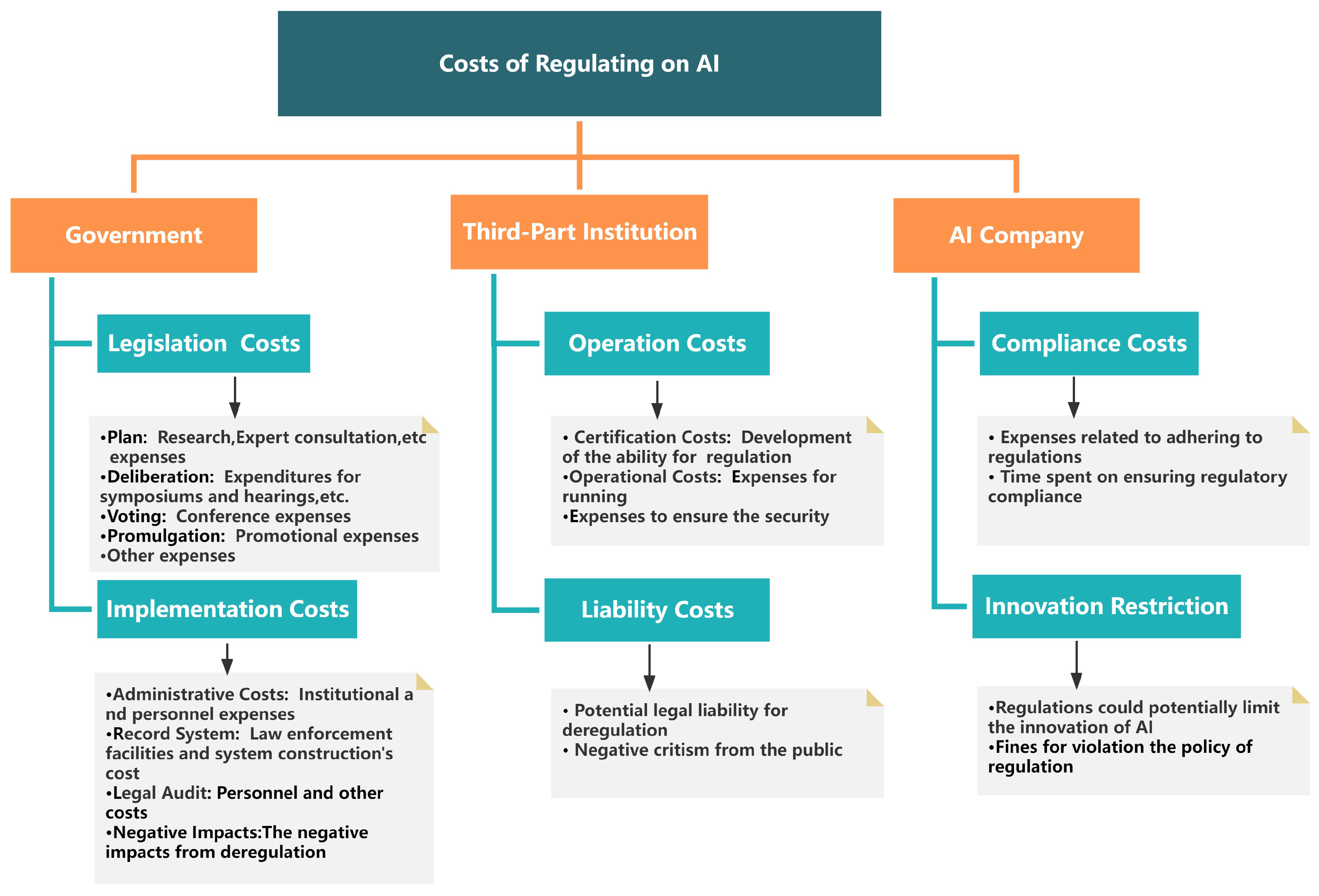

3.1. The Costs of Regulating AI

3.1.1. Regulatory Cost of the Government

3.1.2. Cost of the Third-Party Institution

3.1.3. Cost of the Artificial Intelligence Company

3.2. The Benefits of Regulating Artificial Intelligence

4. Behavioural Evolution in the Regulatory Framework

4.1. Legal Behavior and Expected Payoff

4.2. Stability of different subjects’behavior

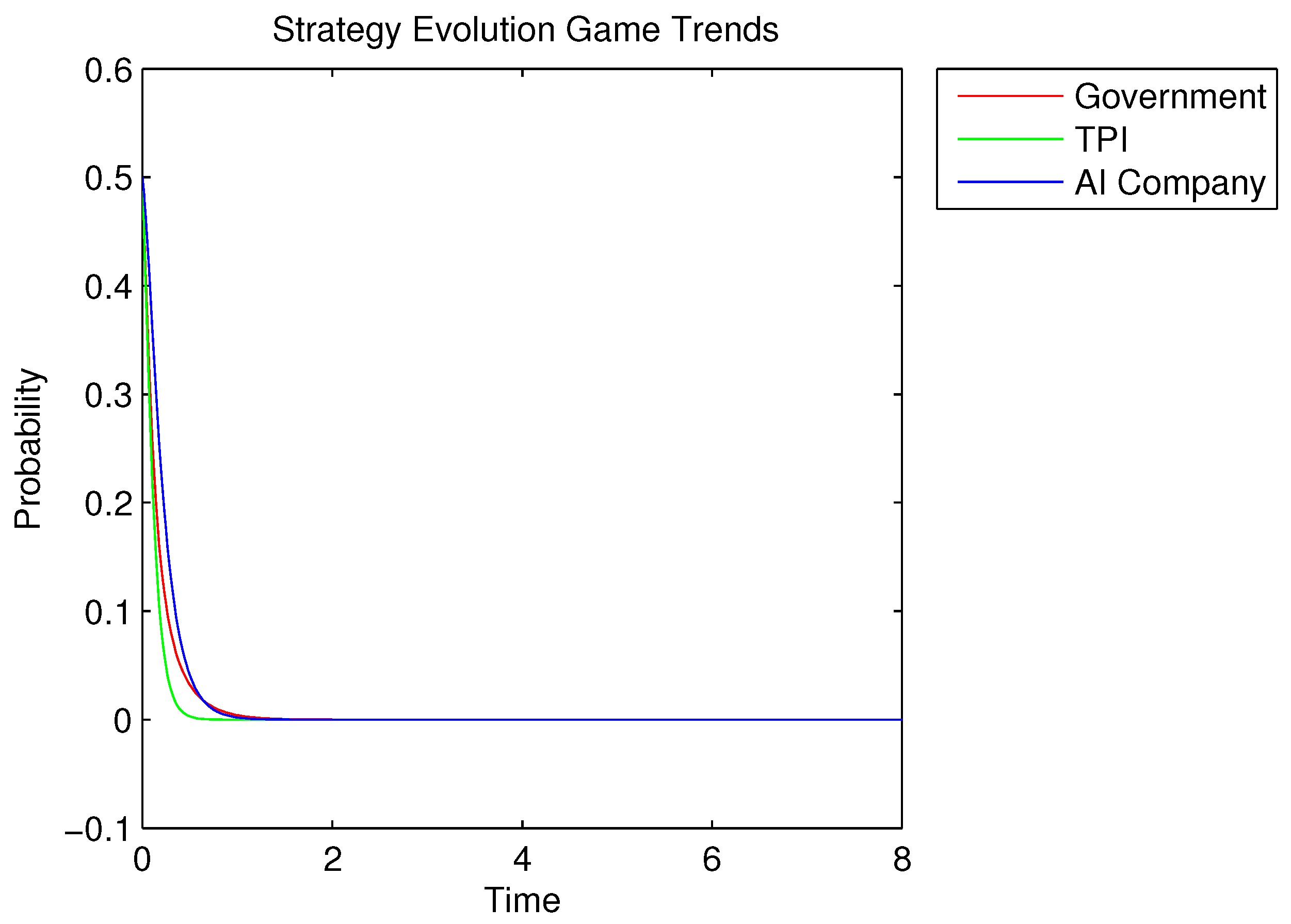

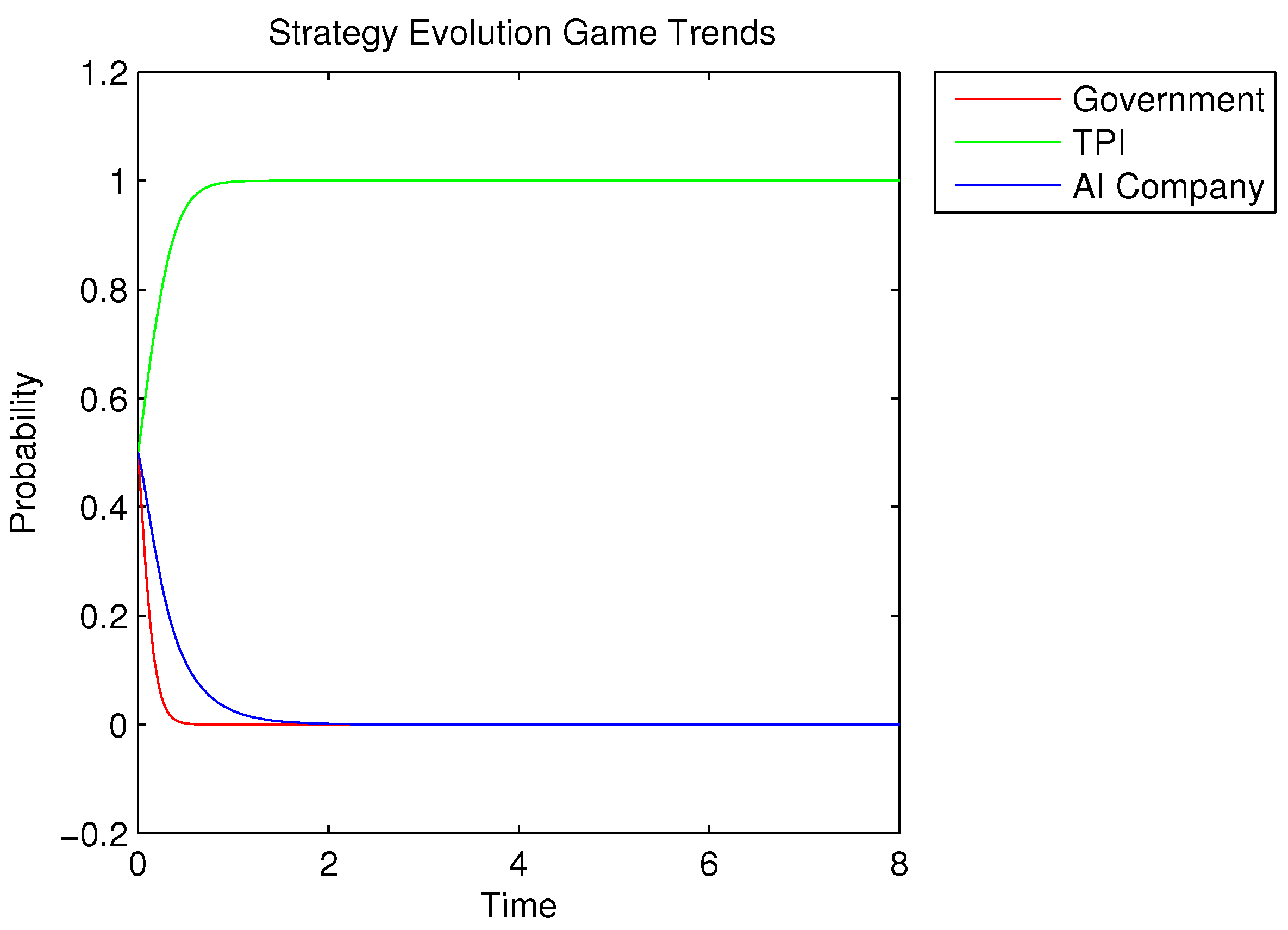

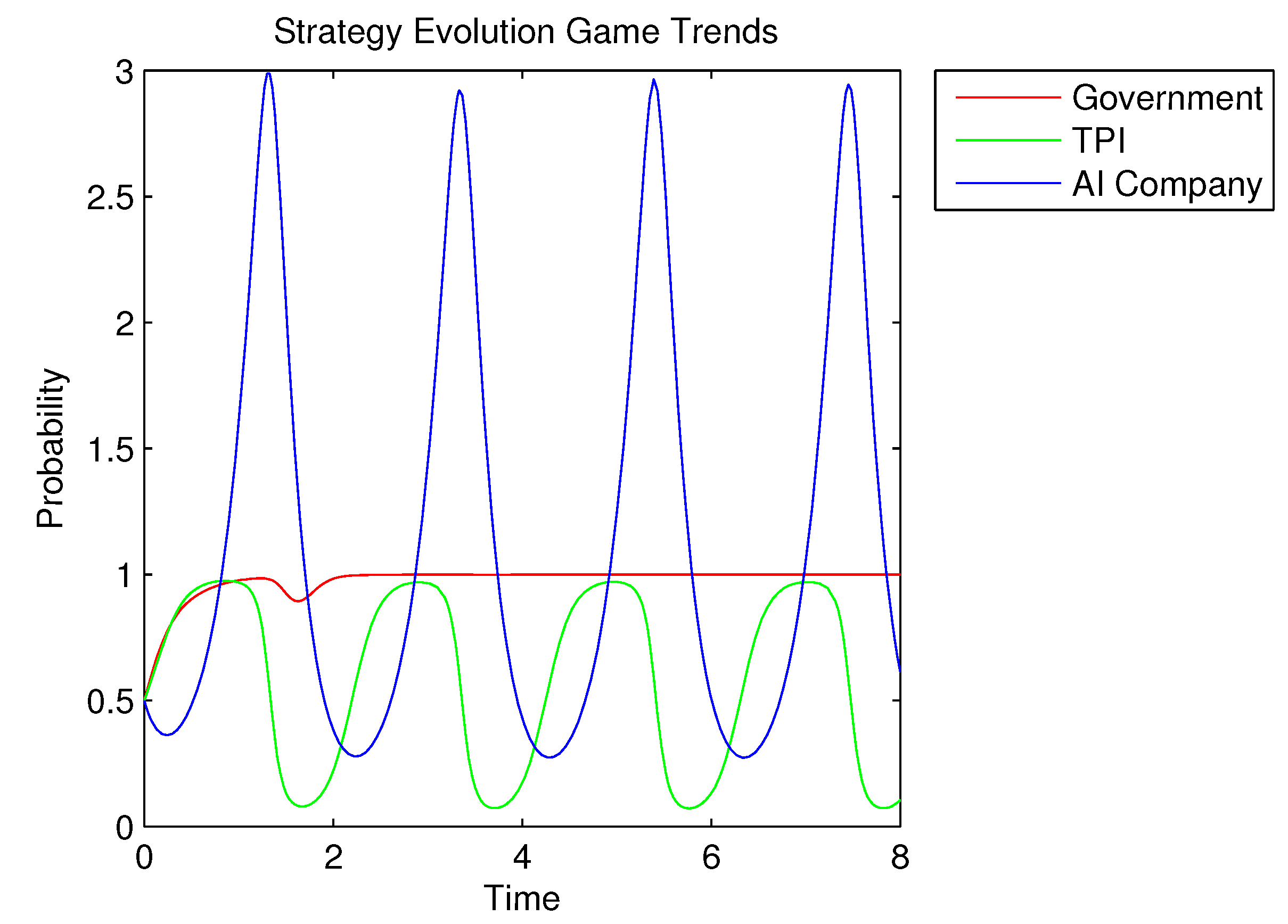

4.3. Simulation Results of the Behavior of Three Subjects

5. Discussion And Conclusion

References

- S. M. J., The Case Against Perfection: Ethics in the Age of Genetic Engineering. Cambrige: Harvard University Press, 2007. [CrossRef]

- T. Kristensen, Artificial Intelligence: Models, Algorithms and Applications. Bentham Science Publishers, 2021. [Online]. Available online: https://books.google.com.tr/books?id=DDY0EAAAQBAJ.

- Price Waterhouse Coopers (2017), ‘Sizing the Prize’. Available online: www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/analytics/assets/pwc-ai-analysis-sizing-the-prize-report.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- A. Sarabi, P. Naghizadeh, Y. Liu, and M. Liu, “Risky business: Fine-grained data breach prediction using business profiles,” Journal of Cybersecurity, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 15–28, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Future of Life Institute,Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter. Available online: https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/ (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Sam Altman,Planning for AGI and beyond. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/planning-for-agi-and-beyond (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- C. Calleja, H. Drukarch, and E. Fosch-Villaronga, “Harnessing robot experimentation to optimize the regulatory framing of emerging robot technologies,” Data & Policy, vol. 4, p. e20, 2022. [CrossRef]

- DPC,Case Studies 2018-2013 booklet. Available online: https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2023-09/DPC_CS_2023_EN_Final.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- IAPP,PRIVACY RISKS STUDY 2023: Five highest, Additional priority privacy, top-ranked compliance risks, and emerging risks. Available online: https://iapp.org/media/pdf/resource_center/privacy_risk_study_infographic_2023.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- M. Saemann, D. Theis, T. Urban, and M. Degeling, “Investigating gdpr fines in the light of data flows,” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, vol. 4, pp. 314–331, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Barnett, Google’s $400m penalty and impact of the 5 heftiest data privacy fines on 2023 ad plans. Available online: https://www.thedrum.com/news/2022/11/15/googles-400m-penalty-the-impact-the-5-heftiest-data-privacy-fines-2023-ad-plans (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Cyberspace Administraion of China, National Cyber Enforcement Efforts Continue to Grow in Effectiveness In 2022. Available online: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2023-01/19/c_1675676681798302.htm (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Fanny Potkin, Supantha Mukherjee,Exclusive: Southeast Asia eyes hands-off AI rules, defying EU ambitions. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/technology/southeast-asia-eyes-hands-off-ai-rules-defying-eu-ambitions-2023-10-11/ (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- J. M. Balkin, “The path of robotics law,” Calif. L. Rev. Circuit, vol. 6, p. 45, 2015.

- T. Wischmeyer and T. Rademacher, Regulating artificial intelligence. Springer, 2020, vol. 1, no. 1.

- COE,What’s AI? Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/artificial-intelligence/what-is-ai (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- N. Nilsson, Artificial Intelligence: A New Synthesis, Elsevier Science,1998.

- European Commission,A definition of AI: Main capabilities and disciplines, Independent High Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence set up by the European Commission, Brussels.

- Inga Ulnicane,Artificial intelligence in the European Union: Policy, ethics and regulation. [CrossRef]

- Pei Wang,What do you mean by ’AI’, Artificial General Intelligence 2008-Proceedings of the First AGI Conference.Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp.362-372,2008.

- S. Hadzovic, S. S. Hadzovic, S. Mrdovic, and M. Radonjic, “A path towards an internet of things and artificial intelligence regulatory framework,” IEEE Communications Magazine, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Manap and A. Abdullah, “Regulating artificial intelligence in malaysia: The two-tier approach,” UUM Journal of Legal Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 183–201, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G.-Z. Yang, J. G.-Z. Yang, J. Bellingham, P. E. Dupont, P. Fischer, L. Floridi, R. Full, N. Jacobstein, V. Kumar, M. McNutt, R. Merrifield et al., “The grand challenges of science robotics,” Science robotics, vol. 3, no. 14, p. eaar7650, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Tschopp and H. Salam, “Spot on sdg 5: Addressing gender (in-) equality within and with ai,” in Technology and Sustainable Development. Routledge, pp. 109–126,2023.

- R. Rayhan and S. Rayhan, “Ai and human rights: Balancing innovation and privacy in the digital age,” 2023.

- A.C. Pigou,The Economics of Welfare,4th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1938). [CrossRef]

- CAHAI, Ad hoc Committee on Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/possible-elements-of-a-legal-framework-on-artificial-intelligence/1680a5ae6b (accessed on 07 November 2023).

- E. Fosch-Villaronga and M. A. Heldeweg, ““meet me halfway,” said the robot to the regulation: Linking ex-ante technology impact assessments to legislative ex-post evaluations via shared data repositories for robot governance,” in Inclusive Robotics for a Better Society: Selected Papers from INBOTS Conference 2018, 16-18 October, 2018, Pisa, Italy. Springer, pp. 113–119, 2020.

- J. Zhao and B. Gómez Fariñas, “Artificial intelligence and sustainable decisions,” European Business Organization Law Review, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 1–39, 2023.

- S. Chatterjee, “Impact of ai regulation on intention to use robots: From citizens and government perspective,” International Journal of Intelligent Unmanned Systems, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 97–114, 2019.

- H. Sheikh, C. H. Sheikh, C. Prins, and E. Schrijvers, Mission AI: The New System Technology. Springer Nature, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Buiten, “Towards intelligent regulation of artificial intelligence,” European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 41–59, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Y. Lau, P. A. Y. Lau, P. Staccini et al., “Artificial intelligence in health: new opportunities, challenges, and practical implications,” Yearbook of medical informatics, vol. 28, no. 01, pp. 174–178, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Reed, “How to make bad law: lessons from cyberspace,” The Modern Law Review, vol. 73, no. 6, pp. 903–932, 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. O’Sullivan and A. Thierer, “Counterpoint: regulators should allow the greatest space for ai innovation,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 33–35, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Hoffmann and B. Hahn, “Decentered ethics in the machine era and guidance for ai regulation,” AI & society, vol. 35, pp. 635–644, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Reed, “How should we regulate artificial intelligence?” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 376, no. 2128, p. 20170360, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. T. Marsden, Net neutrality: Towards a co-regulatory solution. Bloomsbury Academic, 2010.

- A. Shleifer, “Understanding regulation,” European Financial Management, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 439–451, 2005.

- R. Nozick, Anarchy, state, and utopia. John Wiley & Sons, 1974.

- S. Djankov, R. S. Djankov, R. La Porta, F. Lopez-de Silanes, and A. Shleifer, “Courts,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 118, no. 2, pp. 453–517, 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. Djankov, E. S. Djankov, E. Glaeser, R. La Porta, F. Lopez-de Silanes, and A. Shleifer, “The new comparative economics,” Journal of comparative economics, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 595–619, 2003. [CrossRef]

- D. Zimmer, “Property rights regarding data?” p. 101, 2017.

- C. Bloom, J. C. Bloom, J. Tan, J. Ramjohn, and L. Bauer, “Self-driving cars and data collection: Privacy perceptions of networked autonomous vehicles,” in Thirteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, pp.357–375,2017.

- A. Winograd, “Loose-lipped large language models spill your secrets: The privacy implications of large language models,” Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, vol. 36, no. 2, 2023.

- R. Zahid, A. R. Zahid, A. Altaf, T. Ahmad, F. Iqbal, Y. A. M. Vera, M. A. L. Flores, and I. Ashraf, “Secure data management life cycle for government big-data ecosystem: Design and development perspective,” Systems, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 380, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Peck, “The coming connected-products liability revolution,” Hastings LJ, vol. 73, p. 1305, 2022.

- C. R. Sunstein, “The cost-benefit state: the future of regulatory protection.” American Bar Association, 2002.

- D. Baracskay, “Cost-benefit analysis: Concepts and practice,” 1998.

- A. Renda, L. A. Renda, L. Schrefler, G. Luchetta, and R. Zavatta, “Assessing the costs and benefits of regulation,” Brussels: European Commission, 2013.

- R. Axelrod and W. D. Hamilton, “The evolution of cooperation,” science, vol. 211, no. 4489, pp. 1390–1396, 1981. [CrossRef]

- D. Friedman, “Evolutionary games in economics,” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, pp. 637–666, 1991. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Taylor and L. B. Jonker, “Evolutionary stable strategies and game dynamics,” Mathematical biosciences, vol. 40, no. 1-2, pp. 145–156, 1978. [CrossRef]

- A. Tallón-Ballesteros and P. Santana-Morales, “Policy regulation of artificial intelligence: A review of the literature,” Digitalization and Management Innovation: Proceedings of DMI 2022, vol. 367, p. 407, 2023.

- A. Smith, The wealth of nations [1776]. NA, vol. 11937,1937.

- Hirt, E.J.; Clarkson, J.J.; Jia, L. Self-regulation and ego control; Academic Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Subject | Behavior | Parameter | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government | Regulation | y1 | The probability of government regulation |

| U1 | Positive social benefits for government when the TPI proactively regulate | ||

| U2 | Partial social benefits for government | ||

| C1 | The regulatory cost of government | ||

| Deregulation | 1-y1 | Probability that the government will not regulate | |

| N | The negative social impact on the government becomes apparent when the government and the TPI both deregulate | ||

| Third-Party Institution (TPI) | Regulation | C2 | The comprehensive cost of the TPI’s own regulatory costs |

| I1 | The eds from compliance operation when the TPI regulates | ||

| y2 | The probability of the TPI adopting a regulatory strategy | ||

| Deregulation | I2 | Short-term gains obtained when the TPI does not regulate | |

| F | The TPI ’s fine by the government for AI company’ violations | ||

| S | The total loss due to the TPI’s failure to fulfil its regulatory obligations | ||

| 1-y2 | The probability that the TPI does not regulate on AI company | ||

| AI Company | Compliance with regulations | W | Basic income of the compliance operation of the AI company |

| C3 | The cost of running a compliance operation for AI company | ||

| W1 | Surplus revenue generated by AI company’s compliance activities | ||

| y3 | Probability of the AI company’s compliance operation | ||

| Violate regulations | W2 | The additional economic benefits of the illegal activities of the AI company | |

| F2 | the TPI’s punishment on illegal AI company | ||

| 1-y3 | Possibility of the AI company violating regulations |

| Government | Regulation | No Regulation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI Company | ||||

| TPI | ||||

| Regulation, Compliance | U1-C1, I1-C2, W-C3+W1 | U2, I1-C2, W-C3+W1 | ||

| Regulation, Violation | U1-C1, I1-C2+F2, W-C3+W2-F2 | U2, I1-C2+F2, W-C3+W2-F2 | ||

| No Regulation, Compliance | U1-C1, I2, W-C3+W1 | U2, I2, W-C3+W1 | ||

| No Regulation, Violation | U1-C1+F, I2-F-S, W-C3+W2-F2 | -N, I2-S, W-C3+W2 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).