Submitted:

28 December 2023

Posted:

29 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biostimulant Application

2.1.1. Microbial Inoculant

2.1.2. Seed Treatment with Microbial Inoculant

2.1.3. Estimation of Root Colonization by Bacillus sp.

2.2. Plant Material and Experimental Layout

2.3. Determination of Plant Biomass and Total Yield

2.4. Shoot Mineral Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Greenhouse Zucchini Crop

3.2. Open Field Zucchini Squash Crop

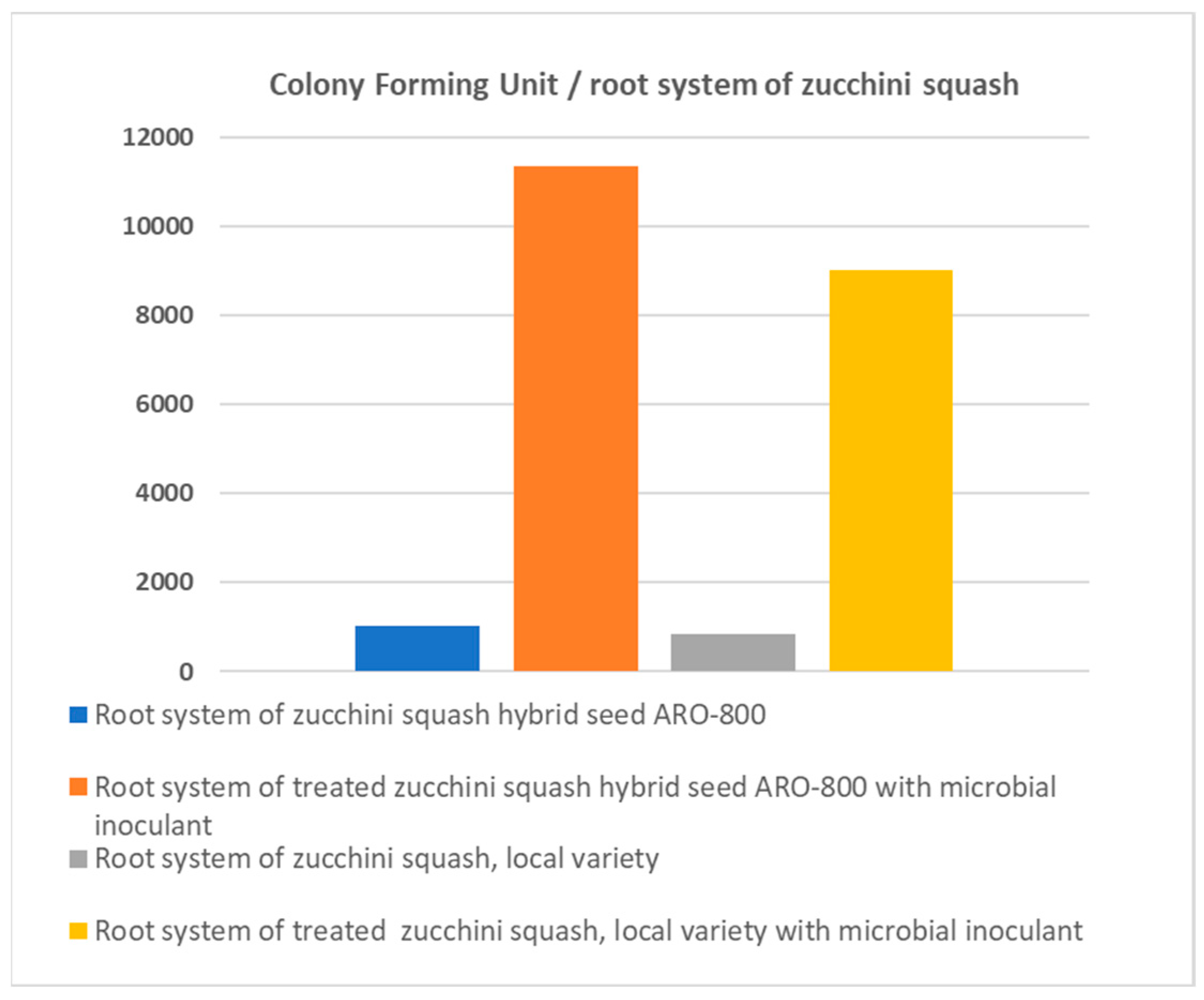

3.3. Root Colonization by PGPR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Dijk, M.; Morley, T.; Rau, M.L.; Saghai, Y. A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050. Nat Food, 2021, 2, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, T.; Chaudhary, A.; Gingrich, S.; Marques, A.; Persson, U.M.; Bidoglio, G.; Provost, G.; Schwarzmüller, F. Global agricultural trade and land system sustainability: Implications for ecosystem carbon storage, biodiversity, and human nutrition. One Earth, 2021, 4, 1425–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Parker, J.E.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Oldroyd, G.E.; Schroeder, J.I. Genetic strategies for improving crop yields. Nature, 2019, 575, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koli, P.; Bhardwaj, N.R.; Mahawer, S.K. Agrochemicals: Harmful and beneficial effects of climate changing scenarios. In Climate Change and Agricultural Ecosystems; K. K. Choudhary, A. Kumar, and A. K. Singh, Ed.; Elsevier: Duxford, 2019; pp. 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.B.; Incrocci, L.; van Ruijven, J.; Massa, D. Reducing contamination of water bodies from European vegetable production systems Agric Water Manage. 2020, 240, 106258. [Google Scholar]

- Tei, F.; De Neve, S.; de Haan, J.; Kristensen, H.L. Nitrogen management of vegetable crops. Agric Water Manage 2020, 240, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; van Gerrewey, T.; Geelen, D. A Meta-Analysis of Biostimulant Yield Effectiveness in Field Trials. Front Plant Sci, 2022, 13, 836702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci Hort, 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.C.; Smith, R.G.; Schipanski, M.E.; Atwood, L.W.; Mortensen, D.A. Agriculture in 2050: Recalibrating targets for sustainable intensification. Biosci 2017, 67, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalozoumis, P.; Savvas, D.; Aliferis, K.; Ntatsi, G.; Marakis, G.; Simou, E.; Tampakaki, A.; Karapanos, I. Impact of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria inoculation and grafting on tolerance of tomato to combined water and nutrient stress assessed via metabolomics analysis. Front Plant Sci, 2021, 12, 670236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Editorial: Biostimulants in agriculture. Front Plant Sci, 2020, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, L.; Consentino, B.B.; Ntatsi, G.; La Bella, S.; Baldassano, S.; Rouphael, Y. Stand-Alone or Combinatorial Effects of Grafting and Microbial and Non-Microbial Derived Compounds on Vigour, Yield and Nutritive and Functional Quality of Greenhouse Eggplant. Plants, 2022, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentino, B.B.; Virga, G.; La Placa, G.G.; Sabatino, L.; Rouphael, Y.; Ntatsi, G.; Iapichino, G.; La Bella, S.; Mauro, R.P.; D’Anna, F.; et al. Celery (Apium graveolens L.) Performances as Subjected to Different Sources of Protein Hydrolysates. Plants, 2020, 9, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentino, B.B.; Aprile, S.; Rouphael, Y.; Ntatsi, G.; De Pasquale, C.; Iapichino, G.; Alibrandi, P.; Sabatino, L. Application of PGPB Combined with Variable N Doses Affects Growth, Yield-Related Traits, N-Fertilizer Efficiency and Nutritional Status of Lettuce Grown under Controlled Condition. Agron, 2022, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in plant science: A global perspective. Front Plant Sci, 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzi, M.; Aroca, R. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria act as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci Hortic, 2015, 196, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, A.; Singh, H.B.; Sen, A. Nutrient use efficiency: From basics to advances; Springer: New Delhi, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wright. B.; Rowse, H.R.; Whipps, J.M. Application of beneficial microorganisms to seeds during drum priming. Biomed Sci Technol, 2003, 13, 599–614. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrini, S.; Merritt, D.; Stevens, J.; Dixon, K. Seed Coating: Science or Marketing Spin? Trends Plant Sci, 2017, 22, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Wen, Q. RNA sequencing analysis of low temperature and low light intensity-responsive transcriptomes of zucchini (Cucurbita pepo L.). Sci Hort, 2020, 265, 109263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Valdivieso, D.; Gómez, P.; Font, R.; Río-Celestino, M.D. Mineral composition and potential nutritional contribution of 34 genotypes from different summer squash morphotypes. Eur Food Res Technol, 2015, 240, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liopa-Tsakalidi, A.; Savvas, D.; Beligiannis, G.N. Modelling the Richards function using Evolutionary Algorithms on the effect of electrical conductivity of nutrient solution on zucchini growth in hydroponic culture. Simu Model Practice Theory 2010, 18, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, I.M.; Siam, H.S.; Abbas, M.H.; Mohamed, I.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Tolba, M.; Abbas, H.H.; Yang, X.; Antoniadis, V.; Rinklebe, J.; Shaheen, S.M. Co-composted biochar derived from rice straw and sugarcane bagasse improved soil properties, carbon balance, and zucchini growth in a sandy soil: A trial for enhancing the health of low fertile arid soils. Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Tullio, M.; Rivera, C.M.; Rea, E. Alleviation of salt stress by arbuscular mycorrhizal in zucchini plants grown at low and high phosphorus concentration. Biol Fertility Soils 2008, 44, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Total nitrogen. Meth Soil Anal: Part 2 chemical and microbiological properties, 1965, 9, 1149–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Toward a sustainable agriculture through plant biostimulants: From experimental data to practical applications. Agron, 2020, 10, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucki, P.; Regdos, K.; Siwek, P.; Domagała-Świątkiewicz, I.; Kaszycki, P. Impact of soil management practices on yield quality, weed infestation and soil microbiota abundance in organic zucchini production. Sci Hort, 2021, 281, 109989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. (2019). Regulation of the european parliament and of the council laying down rules on the making available on the market of EU fertilising products and amending Regulations (EC) No 1069/2009 and (EC) No 1107/2009 and repealing Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2019:170:TOC.

- Viveros, O.M.; Jorquera, M.A.; Crowley, D.E.; Gajardo, G.; Mora, M.L. Mechanisms and practical considerations involved in plant growth promotion by rhizobacteria. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr, 2010, 10, 293–319. [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon, Z.; Huang, S.; Rafique, M.; Fakhar, A.; Kamran, M.A.; Santoyo, G. Unlocking the potential of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on soil health and the sustainability of agricultural systems. J Environ Manage, 2020, 273, 111118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Violante, H.G.; Olalde-Portugal, V. Alteration of tomato fruit quality by root inoculation with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): Bacillus subtilis BEB-13bs. Sci Hort, 2007, 113, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patakioutas, G.; Dimou, D.; Yfanti, P.; Karras, G.; Ntatsi, G.; Savvas, D. Root inoculation with beneficial micro-organisms as a means to control Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici in two Greek landraces of tomato grown on perlite. Acta Hort, 2015, 1107, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, G.; Bajsa, N.; Haghjou, T.; Taulé, C.; Valverde, Á.; Igual, J.M.; Arias, A. Abundance, diversity and prospecting of culturable phosphate solubilizing bacteria on soils under crop–pasture rotations in a no-tillage regime in Uruguay. Appl Soil Ecol, 2012, 61, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, H.I.; Ahmad, F.; Babalola, O. , Inam, A. Growth, photosynthesis and yield of chickpea as influenced by urban wastewater and different levels of phosphorus. Int J Plant Res, 2012, 2, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.E.; Barea, J.M.; McNeill, A.M.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Acquisition of phosphorus and nitrogen in the rhizosphere and plant growth promotion by microorganisms. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 305–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Nazari, M.; Antar, M.; Msimbira, L.A.; Naamala, J.; Lyu, D.; Rabileh, M.; Zajonc, J.; Smith, D.L. PGPR in agriculture: A sustainable approach to increasing climate change resilience. Front Sust Food Sys, 2021, 5, 667546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S. Soil phosphorus. Adv Agron, 1967, 19, 151–210. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R.; Watanabe, F.S. Diffusion of phosphorus as related to soil texture and plant uptake. Soil Sci Soc Amer J, 1963, 27, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Growth, yield, fruit quality and nutrient uptake of hydroponically cultivated zucchini squash as affected by irrigation systems and growing seasons. Sci Hort, 2005, 105, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, D.K.; Dheeman, S. Field crops: Sustainable management by PGPR. Springer 2019, 458. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtaoui, N.; Raklami, A.; Benidire, L.; Tahiri, A.I.; Göttfert, M.; Oufdou, K. Effects of PGPR co-inoculation on growth, phosphorus nutrition and phosphatase/phytase activities of faba bean under different phosphorus availability conditions. Pol J Environ Stud, 2020, 29, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berde, C.V.; Salvi, S.P.; Kajarekar, K.V.; Joshi, S.A.; Berde, V.B. Insight into the animal models for microbiome studies. Springer, 2021, Chapter 13.

- Richardson, A.E. Prospects for using soil microorganisms to improve the acquisition of phosphorus by plants. Funct Plant Biol, 2001, 28, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravel, V.; Antoun, H.; Tweddell, R.J. Growth stimulation and fruit yield improvement of greenhouse tomato plants by inoculation with Pseudomonas putida or Trichoderma atroviride: Possible role of indole acetic acid (IAA). Soil Biol Biochem, 2007, 39, 1968–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. van RAIJ. (1996). Recomendações de adubação e calagem para o Estado de São Paulo (Vol. 100, p. 285p). Campinas: IAC.

- Batista, C.M.; da Mota, W.F.; Pegoraro, R. 9.; Gonçalves, R.E.M.; Aspiazú, I. Production of italian zucchini in response to N and P fertilization. Rev Brasileira Ciências Agr 2020, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, F.I.D.; Grangeiro, L.C.; de Souza, V.D.F.; Gonçalvez, F.D.C.; de Oliveira, F.H.; de Jesus, P.M. X Agronomic performance of Italian zucchini as a function of phosphate fertilization. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, 2018, 22, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchiaze, A.I.; Taffouo, V.D.; Fankem, H.; Kenne, M.; Baziramakenga, R.; Ekodeck, G.E.; Antoun, H. Influence of Nitrogen Sources and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Inoculation on Growth, Crude Fiber and Nutrient Uptake in Squash (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poir.) Plants. Notulae Bot Hort Agroboti Cluj-Napoca, 2016, 44, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, I.; Balaguer, L.; Rincón, A.; Pueyo, J.J. Inoculation of tomato plants with selected PGPR represents a feasible alternative to chemical fertilization under salt stress. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci, 2018, 181, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, G.; Cesaro, P.; Bona, E.; Massa, N.; Gosetti, F.; Scarafoni, A.; Todeschini, V.; Berta, G.; Lingua, G.; Gamalero, E. The effects of plant growth-promoting bacteria with biostimulant features on the growth of a local onion cultivar and a commercial zucchini variety. Agron 2021, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, F.; Fiore, A.; Campanelli, G.; Tittarelli, F.; Ledda, L.; Canali, S. Organic fertilization, green manure, and vetch mulch to improve organic zucchini yield and quality. HortSci, 2013, 48, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genotype | PGPR | Shoot Fresh Weight (kg/plant) | Shoot Dry Weight (g/Plant) | Shoot Dry Matter Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landrace | -PGPR | 1.373 | 106.4 | 7.8 |

| +PGPR | 1.699 | 130.6 | 7.8 | |

| ‘ARO-800′ | -PGPR | 1.616 | 137.8 | 8.6 |

| +PGPR | 1.983 | 160.9 | 8.2 | |

| Main Effects | ||||

| PGPR | ||||

| -PGPR | 1.494 b | 122.1 b | 8.2 | |

| +PGPR | 1.841 a | 145.8 a | 8.0 | |

| Genotype | ||||

| Landrace | 1.536 b | 118.5 b | 7.8 b | |

| ‘ARO-800′ | 1.799 a | 149.4 a | 8.4 a | |

| Significance | ||||

| PGPR | ** | ** | n.s. | |

| Genotype | * | *** | * | |

| PGPR × genotype | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Genotype | PGPR | Mean Fruit Length (cm) | Mean Fruit Weight (g) | Total Yield (kg m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landrace | -PGPR | 16.9 | 146.4 | 1.392 |

| +PGPR | 16.7 | 149.6 | 1.765 | |

| ‘ARO-800′ | -PGPR | 16.6 | 152.4 | 1.991 |

| +PGPR | 16.8 | 156.1 | 2.355 | |

| Main Effects | ||||

| PGPR | ||||

| -PGPR | 16.7 | 149.4 | 1.692 b | |

| +PGPR | 16.8 | 152.8 | 2.060 a | |

| Genotype | ||||

| Landrace | 16.8 | 147.6 b | 1.578 b | |

| ‘ARO-800′ | 16.7 | 154.3 a | 2.173 a | |

| Significance | ||||

| PGPR | n.s. | n.s. | ** | |

| Genotype | n.s. | * | *** | |

| PGPR × genotype | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Genotype | PGPR | Shoot N (mg g−1 d.wt.) |

Shoot P (mg g−1 d.wt.) |

Shoot K (mg g−1 d.wt.) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st SD | 2nd SD | 1st SD | 2nd SD | 1st SD | 2nd SD | ||||

| Landrace | -PGPR | 3.38 | 3.40 | 3.29 | 2.88 | 35.2 | 25.0 | ||

| +PGPR | 3.58 | 3.36 | 4.14 | 3.30 | 35.4 | 28.1 | |||

| ‘ARO-800′ | -PGPR | 3.52 | 3.49 | 2.73 | 3.08 | 35.4 | 29.3 | ||

| +PGPR | 3.68 | 3.51 | 2.82 | 3.33 | 37.2 | 32.9 | |||

| Main Effects | |||||||||

| PGPR | |||||||||

| -PGPR | 3.45 | 3.45 | 3.01 b | 2.98 b | 35.3 | 27.1 | |||

| +PGPR | 3.63 | 3.44 | 3.48 a | 3.32 a | 36.3 | 30.5 | |||

| Genotype | |||||||||

| Landrace | 3.48 | 3.38 | 3.71 a | 3.09 | 35.3 | 26.5 b | |||

| ‘ARO-800′ | 3.60 | 3.50 | 2.77 b | 3.20 | 36.3 | 31.1 a | |||

| Significance | |||||||||

| PGPR | n.s. | n.s. | * | * | n.s. | n.s. | |||

| Genotype | n.s. | n.s. | *** | n.s. | n.s. | * | |||

| PGPR × genotype | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |||

| Genotype | PGPR | Shoot Fresh Weight (kg/Plant) | Shoot Dry Weight (g/Plant) | Shoot Dry Matter Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landrace | -PGPR |

1.373 | 106.4 | 7.8 |

| +PGPR | 1.699 | 130.6 | 7.8 | |

| ‘ARO-800′ | -PGPR |

1.616 | 137.8 | 8.6 |

| +PGPR | 1.983 | 160.9 | 8.2 | |

| Main Effects | ||||

| PGPR | ||||

| -PGPR σπόρου |

1.494 b | 122.1 b | 8.2 | |

| +PGPR | 1.841 a | 145.8 a | 8.0 | |

| Genotype | ||||

| Landrace | 1.536 b | 118.5 b | 7.8 b | |

| ‘ARO-800′ | 1.799 a | 149.4 a | 8.4 a | |

| Significance | ||||

| PGPR σπόρου σπόρου |

** | ** | n.s. | |

| Genotype | * | *** | * | |

| PGPR × genotype σπόρου σπόρου |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Genotype | PGPR | Total Yield (kg m−2) | Fruit Number per m2 | Mean Fruit Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landrace | -PGPR |

1.592 | 14.00 | 113.5 |

| +PGPR | 1.883 | 16.36 | 115.2 | |

| ‘ARO-800′ | -PGPR |

1.601 | 13.67 | 117.2 |

| +PGPR | 2.014 | 17.00 | 118.6 | |

| Main Effects | ||||

| PGPR | ||||

| -PGPR σπόρου |

1.587 b | 13.83 b | 115.3 | |

| +PGPR | 1.942 a | 16.68 a | 116.9 | |

| Genotype | ||||

| Landrace | 1.743 | 15.18 | 114.3 | |

| ‘ARO-800′ | 1.807 | 15.33 | 117.4 | |

| Significance | ||||

| PGPR σπόρου σπόρου |

** | * | n.s. | |

| Genotype | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| PGPR × genotype σπόρου σπόρου |

n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Genotype | PGPR | Shoot N (mg g−1 d.wt.) |

Shoot P (mg g−1 d.wt.) |

Shoot K (mg g−1 d.wt.) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st SD | 2nd SD | 1st SD | 2nd SD | 1st SD | 2nd SD | ||||

| Landrace | -PGPR | 4.78 | 3.40 | 4.90 b | 3.98 | 42.0 | 34.7 | ||

| +PGPR | 5.48 | 3.66 | 6.45 a | 4.14 | 42.5 | 34.3 | |||

| ‘ARO-800′ | -PGPR | 3.99 | 2.97 | 4.32 bc | 3.35 | 33.5 | 25.0 | ||

| +PGPR | 4.08 | 3.58 | 3.69 cd | 4.49 | 36.0 | 29.3 | |||

| Main Effects | |||||||||

| PGPR | |||||||||

| -PGPR | 4.38 | 3.19 | 4.61 | 3.67 b | 37.8 | 29.1 | |||

| +PGPR | 4.78 | 3.62 | 5.07 | 4.32 a | 39.3 | 31.8 | |||

| Genotype | |||||||||

| Landrace | 5.12 | 3.53 | 5.67 | 4.06 | 42.3 a | 34.4 a | |||

| ‘ARO-800′ | 4.03 | 3.28 | 4.00 | 3.92 | 34.8 b | 27.1 b | |||

| Significance | |||||||||

| PGPR | n.s. | n.s. | ns | * | n.s. | n.s. | |||

| Genotype | n.s. | n.s. | * | n.s. | * | * | |||

| PGPR × genotype | n.s. | n.s. | * | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).