Submitted:

28 December 2023

Posted:

29 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

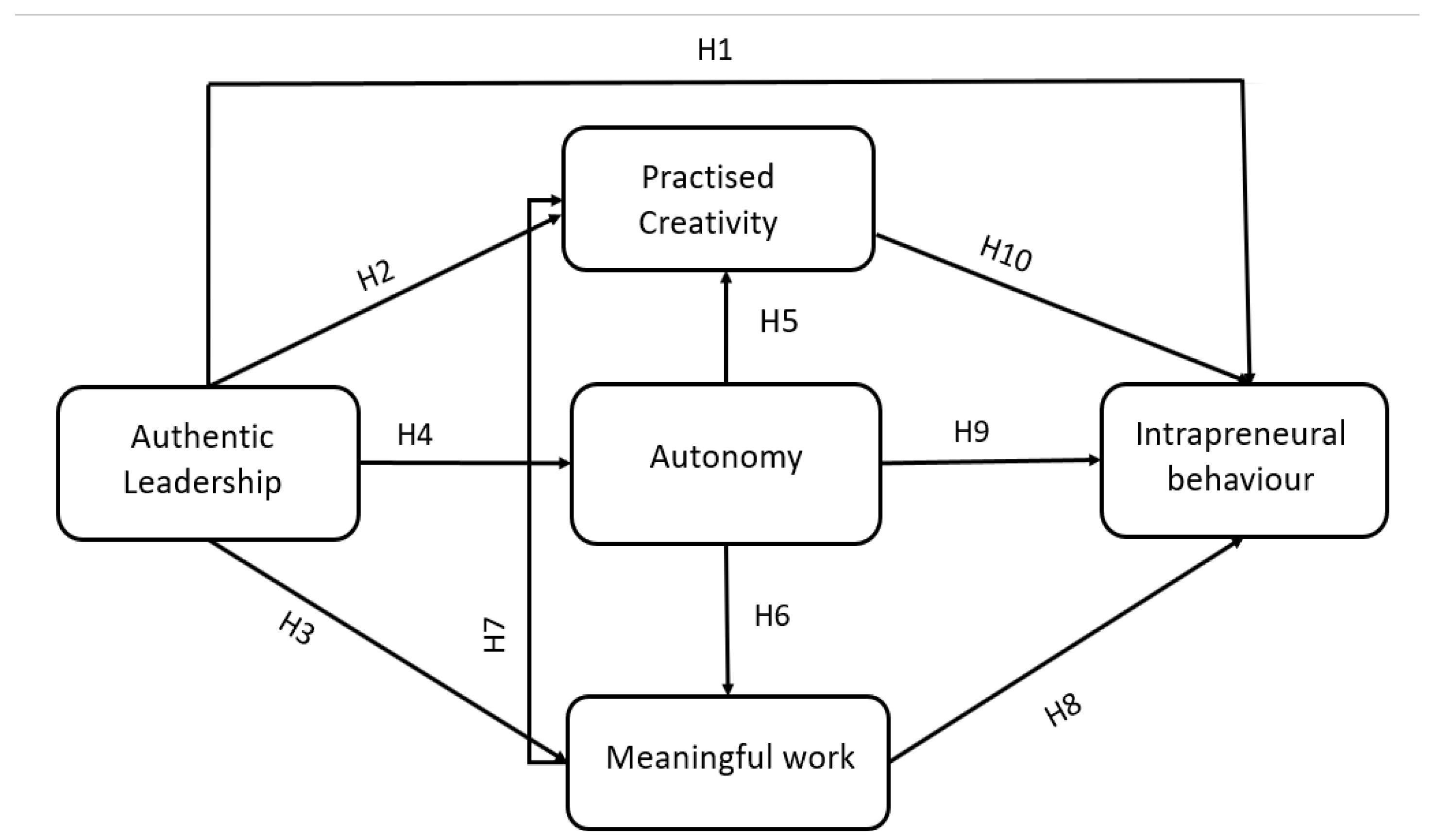

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Data Collection

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Authentic Leadership

2.2.2. Work Autonomy and Meaningful Work (MW)

2.2.3. Practised Creativity

2.2.4. Intrapreneurial Behaviour

2.3. Data Analysis

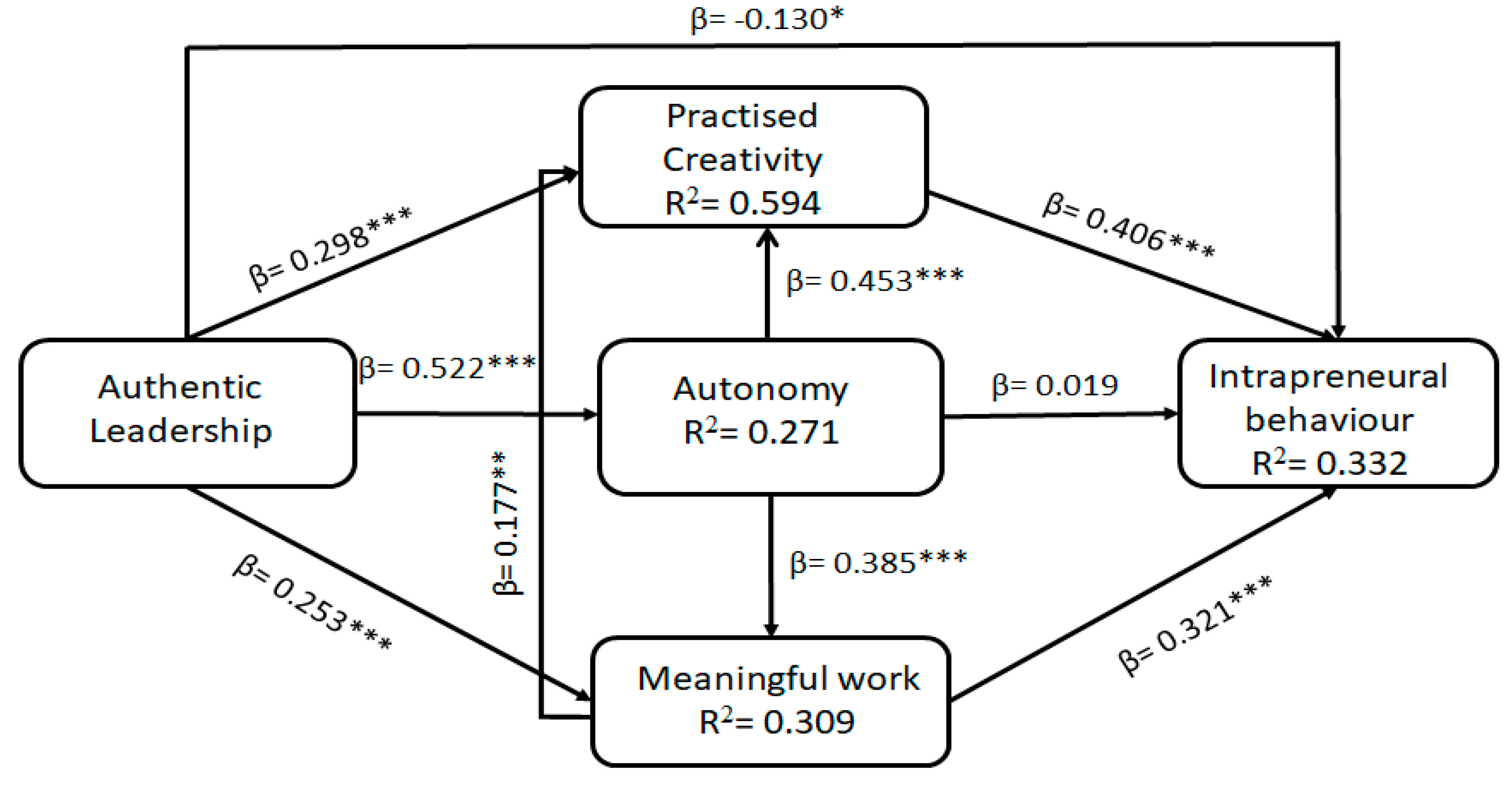

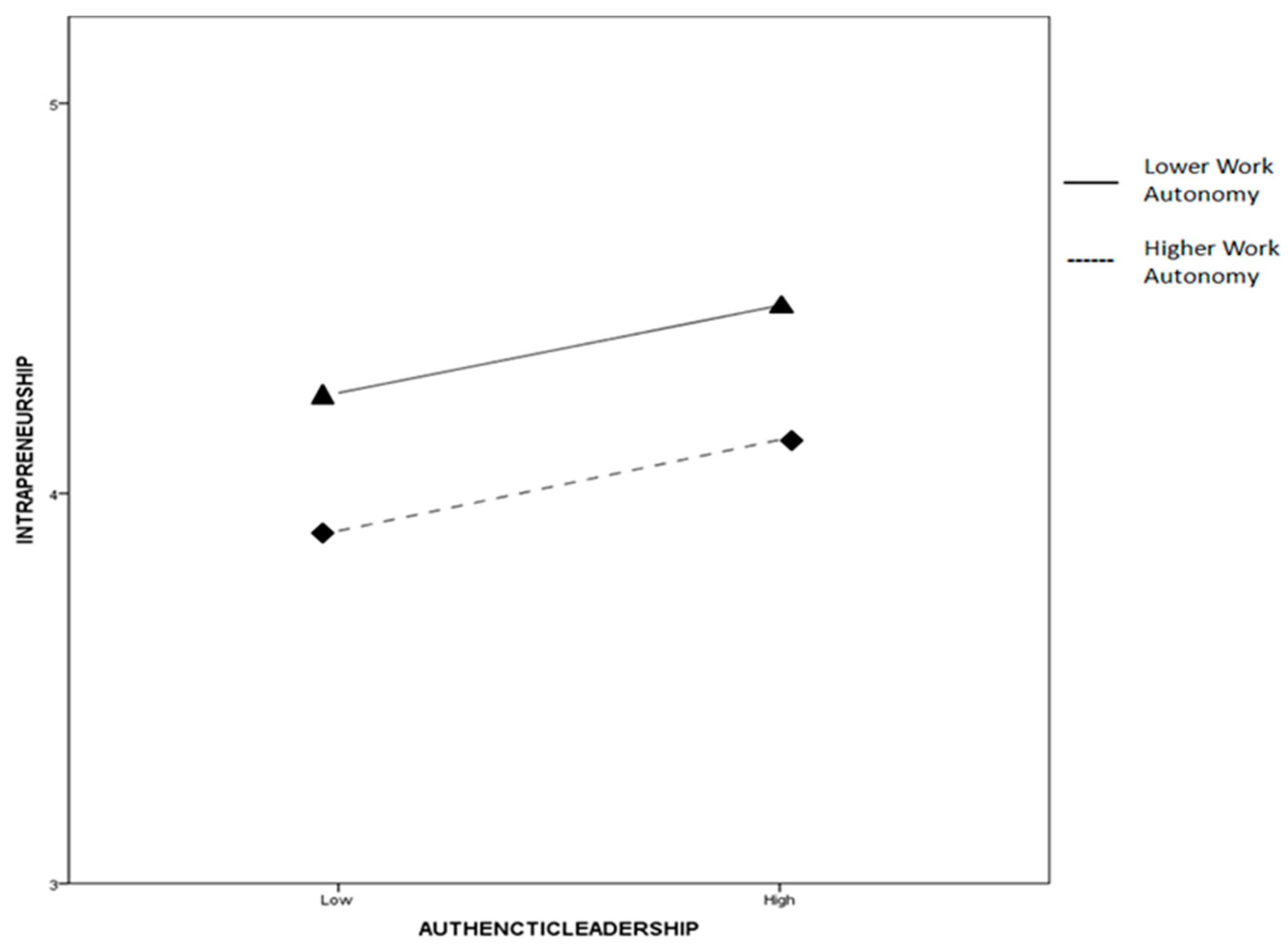

3. Results

To Evaluate the Discriminant

4. Discussion

4.2. Implications and Contributions

4.3. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bretones, F. D. Entrepreneurial employees. In Why Human Capital is Important for Organizations: People Come First; Manuti, A., De Palma P. D. (Eds.), Palgrave McMillan, London, 2014; pp. 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Portalanza-Chavarría, A.; Revuelto-Taboada, L. Driving intrapreneurial behavior through high-performance work systems. Int. Entrep. Manag. J.: 2023, 19, pp. 897-921. [CrossRef]

- Neessen, P. C.; Caniëls, M. C.; Vos, B.; De Jong, J. P. The intrapreneurial employee: toward an integrated model of intrapreneurship and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag: 2019, 15, pp. 545-571. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Blanco-González-Tejero, C. Intrapreneurship research: A comprehensive literature review. J. Bus. Res.: 2022, 153, pp. 428-444. [CrossRef]

- Sieger, P.; Zellweger, T.; Aquino, K. Turning agents into psychological principals: aligning interests of non-owners through psychological ownership. J. Manage. Stud.: 2013, 50, pp. 361-388. [CrossRef]

- Klofsten, M.; Urbano, D.; Heaton, S. Managing intrapreneurial capabilities: An overview. Technovation: 2021, 99, p. 102177. [CrossRef]

- Heinze, K. L.; Weber, K. Toward organizational pluralism: Institutional intrapreneurship in integrative medicine. Organ. Sci.: 2016, 27, pp. 157-172. [CrossRef]

- Howard-Grenville, J.; Golden-Biddle, K.; Irwin, J.;Mao, J. Liminality as cultural process for cultural change. Organ. Sci.: 2011, 22, pp. 522-539. [CrossRef]

- Blanka, C. An individual-level perspective on intrapreneurship: a review and ways forward. Rev. Manag. Sci.: 2019, 13, pp. 919-961. [CrossRef]

- Soltanifar, M.; Hughes, M.; O’Connor, G.; Covin, J. G.; Roijakkers, N. Unlocking the potential of non-managerial employees in corporate entrepreneurship: a systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. of Entrep. Behav. Res.: 2023, 29, pp. 206-24. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, F.; Barlow, P. Entrepreneurship and social capital: a multi-level analysis. Int. J. of Entrep. Behav. Res 2022, 28, pp. 492-519. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Luu, T.; Qian, D. Mediating and moderating effects of task interdependence and creative role identity behind innovation for service: evidence from China and Australia. Int. J. Manpower: 2022, 44, pp. 702-727. [CrossRef]

- Felix, C.; Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D. Leadership as a driver of entrepreneurship: an international exploratory study. J. Small Bus. Manage.: 2019, 26, pp. 397-420. [CrossRef]

- Edú, S.; Moriano, J. A.; Molero, F. Authentic leadership and intrapreneurial behavior: cross-level analysis of the mediator effect of organizational identification and empowerment. Int. Entrep. Manag. J.: 2016, 12, pp. 131-152. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E. I.; Khapova, S. N.; Bossink, B. A. Servant leadership and innovative work behavior in Chinese high-tech firms: A moderated mediation model of meaningful work and job autonomy. Front. Psychol.: 2018, 9, p. 1767. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. M.; Shin, H. C. The Effect of Small Firm CEOs’ Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Innovative Behavior. J. Korean Soc. Qual. Manag.: 2019, 47, pp. 59-74. [CrossRef]

- Mumford, M. D.; Gustafson, S. B. Creativity syndrome: Integration, applicationand innovation. Psychol. Bull.: 1988, 103, pp. 27. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. S.; Melwani, S.; Goncalo, J. A. The bias against creativity: Why people desire but reject creative ideas. Psychol. Sci.: 2012, 23, pp.13-17. [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Qin, C.; Ali, M., Freeman, S.; Shi-jie, Z. The impact of authentic leadership on individual and team creativity: a multilevel perspective. Leadership. Org. Dev. J.: 2021, 42, pp. 644-622. [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Sousa, F.; Marques, C.; Cunha, M. P. Hope and positive affect mediating the authentic leadership and creativity relationship. J. Bus. Res.: 2014, 67, pp. 200-210. [CrossRef]

- Alzghoul, A.; Elrehail, H.; Emeagwali, O. L.; Al Shboul, M. K. Knowledge management, workplace climate, creativity and performance: The role of authentic leadership. J. Workplace Learn.: 2018, 30, pp. 592-612. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback and creative personality. J. Appl. Psychol.: 2003, 88, pp. 413. [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B. D.; Dekas, K. H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav.: 2010, 30, pp. 91-127. [CrossRef]

- Lips-Wiersma, M.; Wright, S. Measuring the meaning of meaningful work: Development and validation of the Comprehensive Meaningful Work Scale (CMWS). Group Organ. Manage.: 2012, 37, pp. 655-685. [CrossRef]

- Jun, K.; Hu, Z.; Lee, J. Examining the Influence of Authentic Leadership on Follower Hope and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Follower Identification. Behav. Sci.: 2023, 13, p. 572. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Authentic leadership and meaningfulness at work: role of employees’ CSR perceptions and evaluations. Manage. Decis.: 2021, 59, pp. 2024-2039. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H.; Anseel, F.; Gardner, W. L.; Sels, L. Authentic leadership, authentic followership, basic need satisfaction and work role performance: A cross-level study. J. Manage: 2015, 41, pp. 1677-1697. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Liu, R.; Long, J. Influence of authentic leadership on employees’ taking charge behavior: the roles of subordinates’ moqi and perspective taking. Front. Psychol.: 2021, 12, p. 626877. [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R. F.; Greenbaum, R.; Hartog, D. N. D.; Folger, R. The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. J. Organ. Behav.: 2010, 31, pp 259-278. [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Dhar, R. L. Authentic leadership and its impact on extra role behaviour of nurses: The mediating role of psychological capital and the moderating role of autonomy. Pers. Rev: 2017, pp 277-296. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Dhar, R. L. Impact of human resources practices on employee creativity in the hotel industry: The impact of job autonomy. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tourism.: 2017, 16, pp 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Sia, S. K.; Appu, A. V. Work autonomy and workplace creativity: Moderating role of task complexity. Glob. Bus. Rev.: 2015, 16, pp. 772-784. [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M. C.; Rietzschel, E. F. Organizing creativity: Creativity and innovation under constraints. Create. Innov. Manag.: 2015, 24, pp. 184-196. [CrossRef]

- Baer, M. Putting creativity to work: The implementation of creative ideas in organizations. Acad. Manage. J.: 2012, 55, pp. 1102-1119. [CrossRef]

- Sia, S. K.; Appu, A.V. Work autonomy and workplace creativity: Moderating role of task complexity. Global Bus. Rev.: 2015, 16, pp. 772-784. [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, C. P.; Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the relation of autonomy to self-regulatory processes and personality development.In Handbook of Personality and Self-regulation 1st ed.; Dr Rick H., Hoyle R.H. Eds.; Wiley Blackwell, 2010, pp. 169-191. [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D. N.; Belschak, F. D. When does transformational leadership enhance employee proactive behavior? The role of autonomy and role breadth self-efficacy. J. Appl. Psychol.: 2012, 97, pp. 194. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Nesbit, P. L. Self-leadership in a Chinese context: Work outcomes and the moderating role of job autonomy. Group Organ. Manage.: 2014, 39, pp. 389-415. [CrossRef]

- Akgunduz, Y.; Alkan, C.; Gök, Ö. A. Perceived organizational support, employee creativity and proactive personality: The mediating effect of meaning of work. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tourism.: 2018, 34, pp. 105-114. [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, S.; Febrianto, Z.; Eliyana, A.; Purwohedi, U.; Anggraini, R. D.; Emur, A. P.; Zahar, M. Proactive personality and organizational support in television industry: Their roles in creativity. Plos one: 2023, 18, pp. e0280003. [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M., & Pratt, M. G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav.: (2016), 36, pp. 157-183. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y. C.; Lin, C. F. Aptitude-treatment interactions during creativity training in e-learning: How meaning-making, self-regulationand knowledge management influence creativity. J. Educ. Tech. Soc.: 2015, 18, pp. 119-131.

- May, D. R.; Gilson, R. L.; Harter, L. M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psych.: 2004, 77, pp. 11-37. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R. W. Innovative behavior in the workplace: The role of performance and image outcome expectations. Acad. Manage. J.: 2010, 53, pp. 323-342. [CrossRef]

- Wipulanusat, W.; Panuwatwanich, K.; Stewart, R. A.; Parnphumeesup, P.; Sunkpho, J. Unraveling key drivers for engineer creativity and meaningfulness of work: Bayesian network approach. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev.: 2020, 11, pp. 293-321. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Jena, L. K. Does meaningful work explains the relationship between transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour? Vikalpa: 2019, 44, pp. 30-40. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Bamel, U.; Vohra, V. The mediating effect of meaningful work between human resource practices and innovative work behavior: a study of emerging market. Emp. Relat. Int. J.: 2021, 43, pp. 459-478. [CrossRef]

- Morse, C. W. The delusion of intrapreneurship. Long. Range. Plann.: 1986, 19, pp. 92-95. [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Dhar, R. Employee service innovative behaviour: The roles of leader-member exchange (LMX), work engagement, and job autonomy. Int. J. Manpower: 2017, 38, pp. 242-258.

- Kuratko, D.F. Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Introduction and Research Review. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research. International Handbook Series on Entrepreneurship, 2 ed Acs, Z., Audretsch, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, 2010; pp. 129-163. [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M.A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav.:1988, 10, pp. 123-167.

- Wang, A. C.; Cheng, B. S. When does benevolent leadership lead to creativity? The moderating role of creative role identity and job autonomy. J. Organ. Behav.: 2010, 31, pp.106-121. [CrossRef]

- Woodman, R. W.; Sawyer, J. E.; Griffin, R. W. Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Acad. Manage. Rev.: 1993, 18, pp. 293-321. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. M.; Sardeshmukh, S. R.; Combs, G. M. Understanding gender, creativityand entrepreneurial intentions. Educ. Train.: 2016, 58, pp. 263-282. [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership. Quart.: 2005, 16, pp. 315-338. [CrossRef]

- Moriano, J. A.; Molero, F.; Lévy, J.P. Authentic leadership. Concept and validation of the ALQ in Spain. Psicothema: 2011, 23, pp 336–341.

- Spreitzer, G. M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurementand validation. Acad. Manage. J.: 1995, 38, pp. 1442-1465. [CrossRef]

- Bretones, F. D.; Jáimez, M. J. Adaptación y validación al español de la Escala de Empoderamiento Psicológico. Interdisciplinaria: 2022, 39, pp. 195-210. [CrossRef]

- DiLiello, T. C.; Houghton, J. D. Creative potential and practised creativity: Identifying untapped creativity in organizations. Creat. Innov. Manag.: 2008, 17, pp. 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Boada Grau, J.; Sánchez García, J. C.; Prizmic Kuzmica, A. J.; Vigil Colet, A. Spanish adaptation of the Creative Potential and Practised Creativity scale (CPPC-17) in the workplace and inside the organization. Psicothema: 2014, 26, pp. 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Stull, M.; Singh, J. Internal Entrepreneurship in Nonprofit Organizations: Examining the Factors that Promote Entrepreneurial Behavior Among Employees. Retrieved May, 2010, pp. 1-13.

- Moriano, J. A.; Topa, G., Valero, E.; Lévy, J. P. Organizational identification and “intrapreneurial” behaviour”. Ann. of Psyc.: 2009, 25, pp. 277-287.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Marketing Res.: 1981, 18, pp. 39-50.

- Hwang, H.; Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J. H.; Ringle, C. M. A concept analysis of methodological research on composite-based structural equation modeling: bridging PLSPM and GSCA. Behaviormetrika: 2020, 47, pp. 219-241. [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods For Business Research, Marcoulides, G. A. (ed), Erlbaum, Mahwah, 1998, pp. 295-336.

- Hair, J. F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, 2017.

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A. G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tourism Manage.: 2021, 86, p. 104330. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

- Hair, J. F.; Black, W. C.; Babin, B. J.; Anderson, R. E. Multivariate data analysis: Pearson new international edition, 7th ed. Pearson Education Limited, Essex, 2014.

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T. K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D. W.; Ketchen, D. J.; Hair, J. F.; Jr., Hult, G. T. M.; Calantone, R. J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Ronkko and Evermann. Organ. Res. Methods: 2014, 17, pp. 182–209. [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J. F.; Cheah, J. H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C. M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Marketing: 2019, 53, pp. 2322-2347. [CrossRef]

- Carrión, G. C.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C. M.; Roldán, J. L. Prediction-oriented modeling in business research by means of PLS path modeling: Introduction to a JBR special section. J. Bus. Res.: 2016, 69, pp. 4545-4551. [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A. G. Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. J. Bus. Res.: 2013, 66, pp. 463-472. [CrossRef]

- Sagbas, M.; Oktaysoy, O.; Topcuoglu, E.; Kaygin, E.; Erdogan, F.A. The Mediating Role of Innovative Behavior on the Effect of Digital Leadership on Intrapreneurship Intention and Job Performance. Behav. Sci.: 2023, 13, p. 874. [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Lee, J. W. C.; Shahzad, I. A. Intrapreneurial behavior in higher education institutes of Pakistan: The role of leadership styles and psychological empowerment. J. Appl. Res. Hig. Educ.: 2019, 11, pp. 273-294. [CrossRef]

- Černe, M.; Jaklič, M.; Škerlavaj, M. Authentic leadership, creativity, and innovation: A multilevel perspective. Leadership: 2013, 9, pp. 63-85. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S. D.; Alge, B. J.; Brown, M. E.; Jackson, C. L.; Dunford, B. B. Ethical leadership: Assessing the value of a multifoci social exchange perspective. J. Bus. Ethics: 2013, 115, pp. 435-449. [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L. G.; Knies, E. Leadership and meaningful work in the public sector. Public Admin. Rev.: 2013, 73, pp. 859-868. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, C. T.; Kavussanu, M. Authentic leadership in sport: Its relationship with athletes’ enjoyment and commitment and the mediating role of autonomy and trust. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coa.: 2018, 13, pp. 968-977. [CrossRef]

- Pashazadeh, F.; Alavinia, P. Teacher creativity in light of autonomy and emotional intelligence. Teach. Engl. Lang.:2019, 13, pp. 177-203. [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, A.; Haar, J. Organisational-based self-esteem, meaningful workand creativity behaviours: A moderated mediation model with supervisor support. New Zealand J. of Emp. Relat.: 2019, 44, pp. 11-3.

- Balková, M.; Lejsková, P.; Ližbetinová, L. The values supporting the creativity of employees. Front. Psychol.: 2022, 12, p. 805153. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Vergara, M.; Alvarez-Marin, A.; Placencio-Hidalgo, D. A bibliometric analysis of creativity in the field of business economics. J. Bus. Res.: 2018, 85, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

| Latent variables | Ítems | Outer loading | VIF | AVE | Alfa Cronbach | CR |

| Authentic leadership | AL_2 | 0.774 | 2.432 | 0.598 | 0.951 | 0.957 |

| AL_3 | 0.841 | 3.524 | ||||

| AL_4 | 0.704 | 1.902 | ||||

| AL_5 | 0.691 | 1.894 | ||||

| AL_6 | 0.816 | 3.003 | ||||

| AL_7 | 0.635 | 1.817 | ||||

| AL_8 | 0.778 | 2.316 | ||||

| AL_9 | 0.826 | 2.894 | ||||

| AL_10 | 0.779 | 2.499 | ||||

| AL_11 | 0.723 | 2.193 | ||||

| AL_12 | 0.853 | 4.599 | ||||

| AL_13 | 0.880 | 2.023 | ||||

| AL_14 | 0.653 | 3.143 | ||||

| AL_15 | 0.829 | |||||

| AL_16 | 0.770 | 2.446 | ||||

| Work Autonomy | WA_1 | 0.825 | 2.434 | 0.763 | 0.895 | 0.928 |

| WA_2 | 0.837 | 3.072 | ||||

| WA_3 | 0.894 | 4.072 | ||||

| WA_4 | 0.933 | 1.996 | ||||

| Practised creativity | PC_1 | 0.842 | 2.291 | 0.624 | 0.848 | 0.892 |

| PC_2 | 0.826 | 2.123 | ||||

| PC_3 | 0.685 | 1.498 | ||||

| PC_4 | 0.765 | 1.630 | ||||

| PC_5 | 0.823 | 1.993 | ||||

| Meaningful Work | MW_1 | 0.876 | 1.975 | 0.714 | 0.798 | 0.882 |

| MW_2 | 0.889 | 2.227 | ||||

| MW_3 | 0.764 | 1.456 | ||||

| Intrapreneurial behaviour | IB_1 | 0.739 | 1.660 | 0.580 | 0.856 | 0.892 |

| IB_2 | 0.796 | 1.917 | ||||

| IB_3 | 0.714 | 1.923 | ||||

| IB_5 | 0.726 | 2.070 | ||||

| IB_6 | 0.755 | 2.168 | ||||

| IB_7 | 0.832 | |||||

| Note:CR= composite reliability; AVE= Average variance extracted | ||||||

| Fornell- Larcker | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | WA | PC | IB | AL | MW | ||

| Work Autonomy (WA) | 5.19 | 1.165 | 0.873 | |||||

| Practised Creativity (PC) | 3.72 | 0.787 | 0.683** | 0.790 | ||||

| Intrapreneurial Behaviour (IB) | 3.74 | 0.677 | 0.385** | 0.489** | 0.761 | |||

| Authentic Leadership (AL) | 3.46 | 0.949 | 0.489** | 0.486** | 0.249** | 0.774 | ||

| Meaningful Work (MW) | 5.51 | 0.914 | 0.338** | 0.537** | 0.498** | 0.338** | 0.845 | |

| Note: Square root of AVE on diagonal; correlations between constructs are shown below the diagonal; *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01 | ||||||||

| Hypothesis | Coefficient | CI | P Values | T Statistics | F2 | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: AL-> IB | -0.130 | (-0.252; -0.004) | 0.040 | 2.054 | 0.015 | Partial |

| H2:AL -> PC | 0.298 | (0.218; 0.380) | 0.000 | 7.368 | 0.151 | Yes |

| H3: AL-> MW | 0.253 | (0.150; 0.359) | 0.000 | 4.743 | 0.068 | Yes |

| H4: AL ->WA | 0.522 | (0.448; 0.594) | 0.000 | 13.853 | 0.375 | Yes |

| H5: WA-> PC | 0.453 | (0.341;0.550) | 0.000 | 8.484 | 0.321 | Yes |

| H6: WA-> MW | 0.385 | (0.253; 0,506) | 0.000 | 5.924 | 0.157 | Yes |

| H7: MW-> PC | 0.177 | (0.062; 0.295) | 0.003 | 3.007 | 0.054 | Yes |

| H8: MW -> IB | 0.321 | (0.203; 0.429) | 0.000 | 5.513 | 0.102 | Yes |

| H9: WA-> IB | 0.019 | (-0.138;0.171) | 0.811 | 0.239 | 0.000 | No |

| H10: PC->IB | 0.406 | (0.269; 0.549) | 0.000 | 5.663 | 0.100 | Yes |

| Note: WA= Work Autonomy; Al= Authentic leadership; PC=Practised Creativity; MW= Meaningful Work; IB= Intrapreneurial behaviour | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).