1. Introduction

The modern healthcare landscape faces a significant challenge: the rising prevalence of chronic diseases influenced by dietary factors. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, and other conditions pose a global health threat. Good nutrition is increasingly recognized as a critical tool for preventing non-communicable disease (NCDs) [

1]. Recent evidence has underscored the profound impact of dietary habits on individual’s health, linking poor diet and obesity to heightened disease risk [

2]. As public awareness grows regarding the role of nutrition in disease etiology, healthcare professionals (HCPs) are expected to deliver a comprehensive care that bridges diet and disease. However, it is a common perception that they often face challenges such as insufficient skills, confidence, and time to deliver such comprehensive care.

High-quality nutrition in disease management necessitates not only in-depth nutritional assessment but also an emphasis on various other aspects. This includes impactful, resource-efficient interventions, policy measures, and community and clinical initiatives [

3]. Educational programs, particularly those focused on culinary medicine (CM), offer a promising solution. CM, an evidence-based approach that integrates cooking skills with medical knowledge, empowers individuals to use food and beverages as a primary therapeutic tool [

4]. Systematic reviews (28 from January 1980 to December 2011[

5], and 34 studies from January 2011 to March 2016) [

6], have shown positive outcomes of cooking programs on dietary habits, health status, and psychosocial outcomes in adults, highlighting the importance of these approaches [

4,

7]. Research also suggests that interventions targeted at patients and medical students, which involve home food preparation and hands-on experience in meal preparation, can lead to favorable changes in dietary habits, food choices, and related factors among adults [

5,

6,

8]. Further studies like PREDIMED-Plus emphasize the benefits of a healthy Mediterranean Diet (MD) in managing comorbidities [

9], and CM trainings also aim to equip HCPs with strategies and skills to enhance adherence to such diets.

Moreover, Nutrition care is increasingly recognized as a pivotal tool for enhancing patient experience [

10]. Malnutrition-related disorders are well-documented to adversely impact various aspects of life, including social interactions, family caregiving, mood, sleep, cognitive and physical functions, sense of self, and overall quality of life [

11,

12]. This understanding aligns with the evolving perception of healthcare quality and value. Michael E. Porter posits that high-quality healthcare is defined by its ability to enhance value from the patient or caregiver’s perspective [

13]. Consequently, initiatives that improve patient experience should be prioritized, particularly those like CM, which are cost-effective and straightforward to implement [

7]. The social dimension of nutrition, including concepts like "mindful eating" [

14] emphasizes choosing foods based on personal preferences and taste, reducing food waste, and adopting sustainable practices [

15]. The goal is not to advocate for drastic alterations in dietary habits but to gradually integrate minor changes into daily routines, fostering sustainable, health-conscious culinary habits.

With this background, we hypothesized that HCPs receiving training in CM - encompassing healthy eating, cooking, meal preparation, selection of locally sourced and seasonal products, and strategies for habit change - would be more likely to adopt and share these practices with their peers and patients. This transfer of knowledge and skills represents a critical step in accomplishing the objectives of CM.

The primary goal of this project was to endow different types of HCPs with educational strategies focusing on healthier diets that would improve their skills and confidence on nutritional management of their patients.

Therefore, our aim was to examine the impact of the intervention not only for HCPs but also on their ability to transfer knowledge and practices to their patients and the broader healthcare community by assessing their increased adherence to the Mediterranean diet, beliefs in the efficacy of nutrition counseling, confidence on counseling, food management abilities, and culinary skills, and bolstering their capacity to guide, coach, and instruct patients requiring dietary guidance.

2. Materials and Methods

We executed a four-day pilot implementation program (PIP) with a cohort of 20 HCPs from Hospital Clinic Barcelona. The program was held at Alícia Foundation (ALICIA) facilities; a local private non-profit foundation dedicated to culinary innovation, healthier eating habits, reducing food waste, and promoting gastronomic heritage. The educational curriculum -designed jointly by dietitians and chefs- combined nutritional and culinary education. The program included sessions on CM, food management, culinary skills, and culinary diet therapy, focusing on prevalent diseases, their prevention, treatment, and care.

Table 1 shows a detailed list of the activities carried out.

For evaluation, given the lack of specific surveys to assess the acquisition of knowledge of this particular skill set, we conducted pre- and post-program surveys among participants combining existing surveys with

ad hoc questions. These surveys aimed to evaluate their perceived nutrition knowledge and counseling skills, as well as their personal dietary choices. The pre-program survey served as the baseline, gauging the professionals’ perspective, expectation, and initial knowledge, and comprised socio-demographic questions plus two other differentiated sections. Socio-demographic items collected information about sex, age range, profession, and if any prior training in nutrition or cooking. The first section included the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS-14) [

16]. This semi-quantitative questionnaire assessed adherence on a continuous 0–14-point scale, categorizing participants into low (<5 points), medium (6 to 8 points), and high (>9 points) adherence levels. The second section evaluated culinary knowledge across four domains: food and diet therapy, food management, culinary skills, and confidence around food and cooking. In the food and diet therapy domain, we use a 1-to-5 scale (1, for strongly agree and 5 for strongly disagree) to measure perceptions of diet therapy knowledge and its expectations and the perceived importance of nutrition. For food management, participants rated their proficiency in various skills on a 1-to-7 scale, with 1 being the lowest and 7 the highest skill level. Culinary skills were assessed by asking about their frequency of cooking (per week) and proficiency in specific skills, again rated on a 1-to-7 scale, with "never / rarely" as an option for unpracticed skills. Confidence in nutrition and cooking was measured on a 0-to-7 scale, with 0 being the lowest and 7 the highest level of confidence.

Two months after the conclusion of the training course, a post-program survey was conducted to gauge the effects of the course on the participants in time. This time span was selected as an effort to avoid recalling bias as possible. This survey revisited topics covered in the pre-program survey, focusing on culinary knowledge and adherence to the Mediterranean diet. It also included a comprehensive evaluation of the course itself, aiming to understand if and how the training had altered the professional's perspective and practices. The survey’s assessment on the training activity was primarily qualitative, utilizing a series of open-ended questions. The following questions sought to capture the participants’ reflections on the course’s impact on their attitude toward nutrition and patient care: ‘Has this course changed your attitude in relation to nutrition and patient care? If so, how? And “How do you see yourself integrating any of the skills learned in the course with your patients? Additionally, participants were encouraged to share their thoughts on the strengths of the course and any suggestions for improvement with the following questions:, “What do you think has been the strong point of the course? And “What proposals for improvement do you propose in relation to the course?

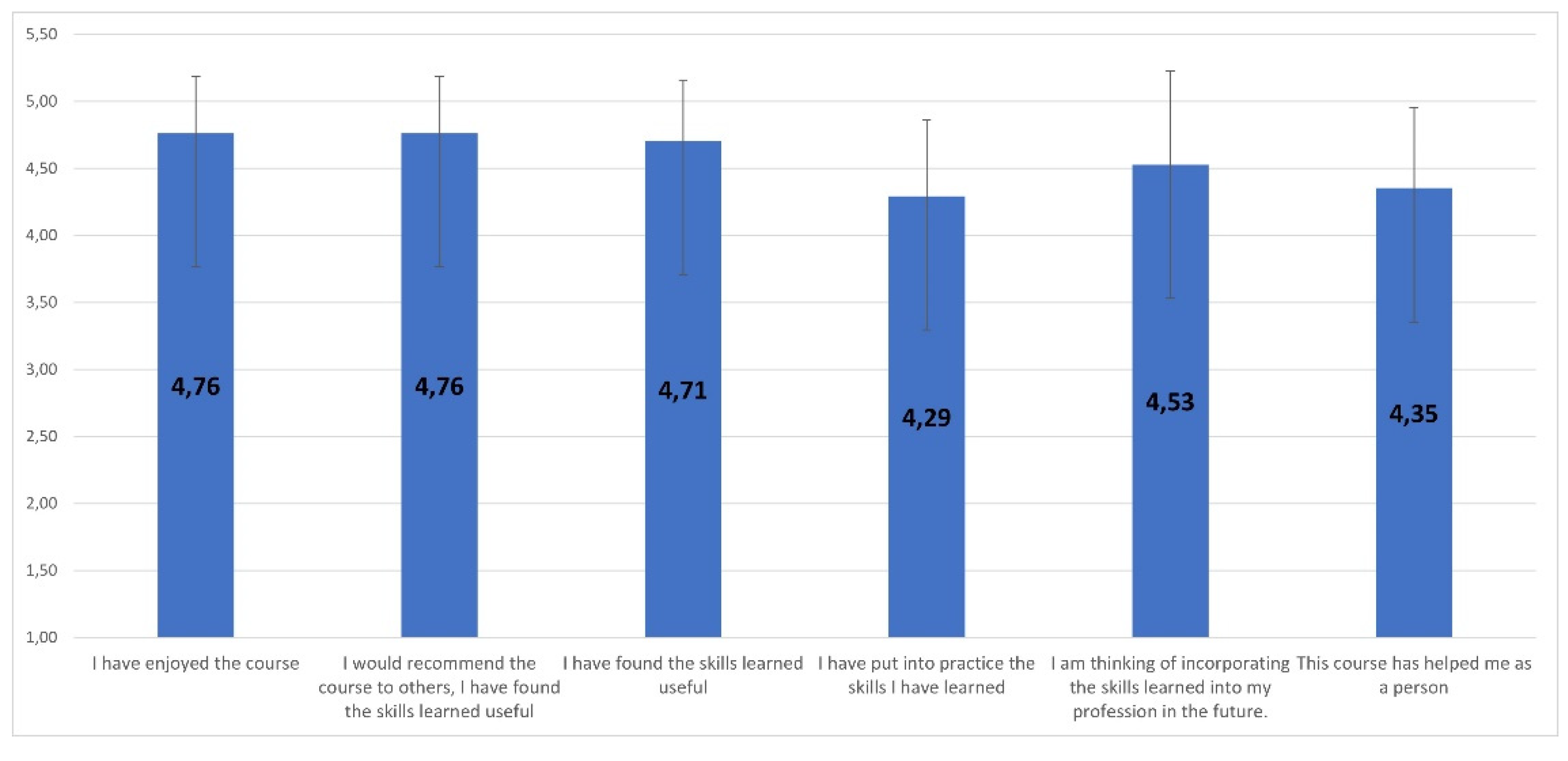

To further qualify their experience, participants were asked to mark their responses to statements as “I have enjoyed the course,” “I would recommend the course to others”, “I have found the skills learned useful”, “I have put the skills I have learned into practice”, “I am thinking about incorporating the skills learned into my profession in the future”, and “This course has helped me as a person”. These statements were designed to capture the overall satisfaction with the course, the perceived utility of the skills learned, and the integration of these skills into both their professional and personal lives.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

To analyze the reported change in variables post-program, we employed the Mann-Whitney U test. This non-parametric test was chosen for its suitability in comparing differences between two independent groups when the dependent variable is either ordinal or continuous, but not normally distributed. The use of the Mann-Whitney U test allowed us to assess whether the ranks of the two groups differed significantly. We utilized Chi-square analysis to examine the relationship between participation in the course and a positive response to each survey item. This helped us determine if there was a statistically significant association between course participation and the likelihood of a positive survey response. Additionally, we conducted two-tailed paired Student’s t-tests to compare the means between two groups. This test was particularly relevant for assessing differences between pre- and post-program responses, as it accounts for the paired nature of our data, where the same subjects were surveyed before and after the program. For the description of results, we calculated means and standard deviations (SDs) using Microsoft Excel. These descriptive statistics provided an overview of the central tendency and variability within our data set.

While free-text comments from the surveys provided valuable insights, they were not subjected to formal qualitative analysis. Instead, these comments served as complementary data, enriching our understanding of the quantitative findings, and providing context and depth to statistical results.

2.2. Study Limitations

While our study sought to comprehensively assess the impact of a Culinary Medicine (CM) training program on healthcare professionals (HCPs) and their subsequent ability to transfer knowledge to their patients and the broader healthcare community, certain limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size of our study, comprising 20 HCPs from Hospital Clinic Barcelona, may limit the generalizability of our findings to broader healthcare settings. This sample size was due to the facility constraints of Alicia Foundation, where the program was conducted. Although suit for a PIP, the sample size it was bound to might have ebbed the potency for statistical analysis to distinguish differences in some cases. Moreover, the homogeneity of the sample, with participants drawn from a single institution, may influence the diversity of perspectives and experiences, potentially limiting the external validity of our results. Additionally, our reliance on a self-reported survey methodology, while practical for capturing participants' perceptions, introduces the possibility of response or recall bias, as participants may have provided socially desirable responses or may recall their pre-program attitudes and practices partially. Furthermore, the absence of a control group hinders our ability to establish a direct causal link between the CM training and observed changes, as external factors could also contribute to some of the reported outcomes. Finally, the short-term nature of our post-program survey, conducted two months after the conclusion of the training, may not capture longer-term effects, and a more extended follow-up period could provide a more comprehensive understanding of sustained changes in HCPs' practices and attitudes. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and planning future research endeavors in the field of culinary medicine education for healthcare professionals.

3. Results

Sociodemographic profile: Of the initial HCP that completed the training program, 70% completed both surveys. Participants were composed by 86% female participants, and 71% were nurses. Training in nutrition was stated by 86% of participants and culinary training was declared by 14% of participants (

Table 2).

Mediterranean Diet Adherence: There was a statistically significant improvement in overall adherence to the Mediterranean diet, as MEDAS-14 scores improved from 9.8 (SD=2.0) to 10.8 (SD=1.9) (p<0.01). However, when improvements in food management skills, culinary skills, or counseling confidence were evaluated no significant improvements were noted (

Table 3).

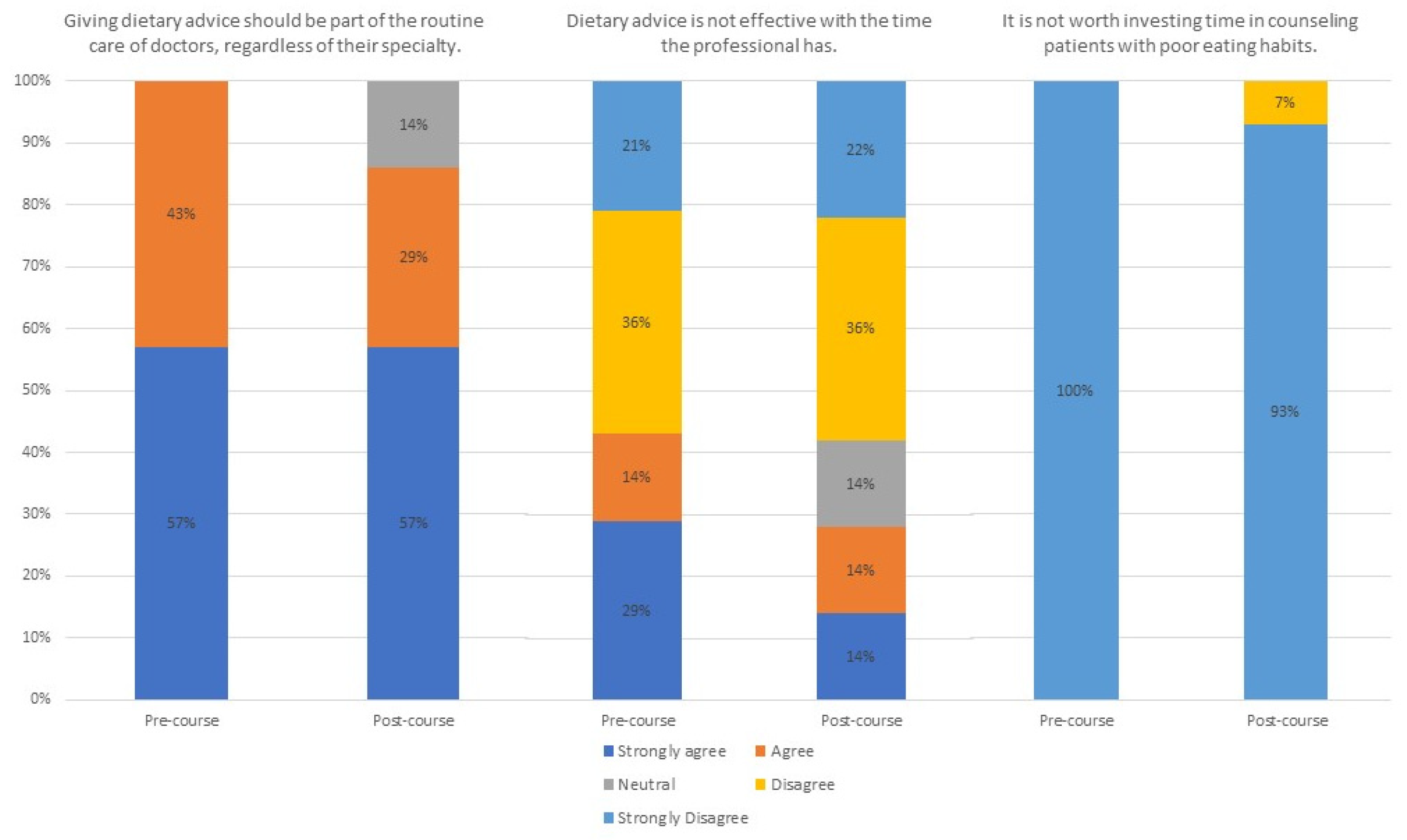

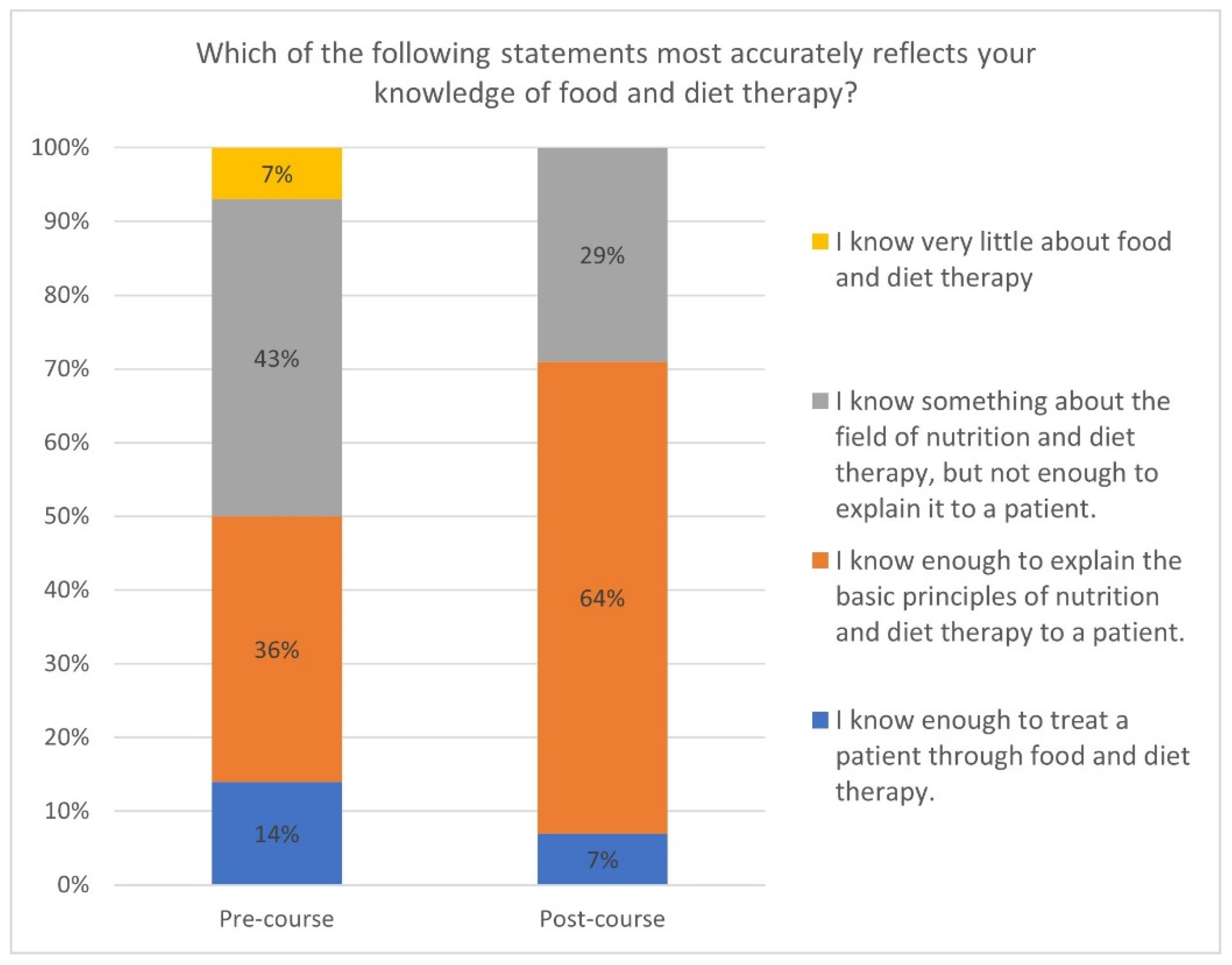

Food and Diet Therapy Knowledge: When comparing pre- and post- surveys, agreement on the relevance of giving dietary advice (regardless of specialty) and the worthiness of investing time in eating habits counseling were maintained. However, previously to the pilot 29% of professionals strongly agreed that dietary advice is ineffective due to time constraints and this percentage was diminished to 14% two months after the course (

Figure 1). A perceived increase in knowledge about food and diet therapy post-program was also detected switching from 36% of the pre-course respondents to 64% (

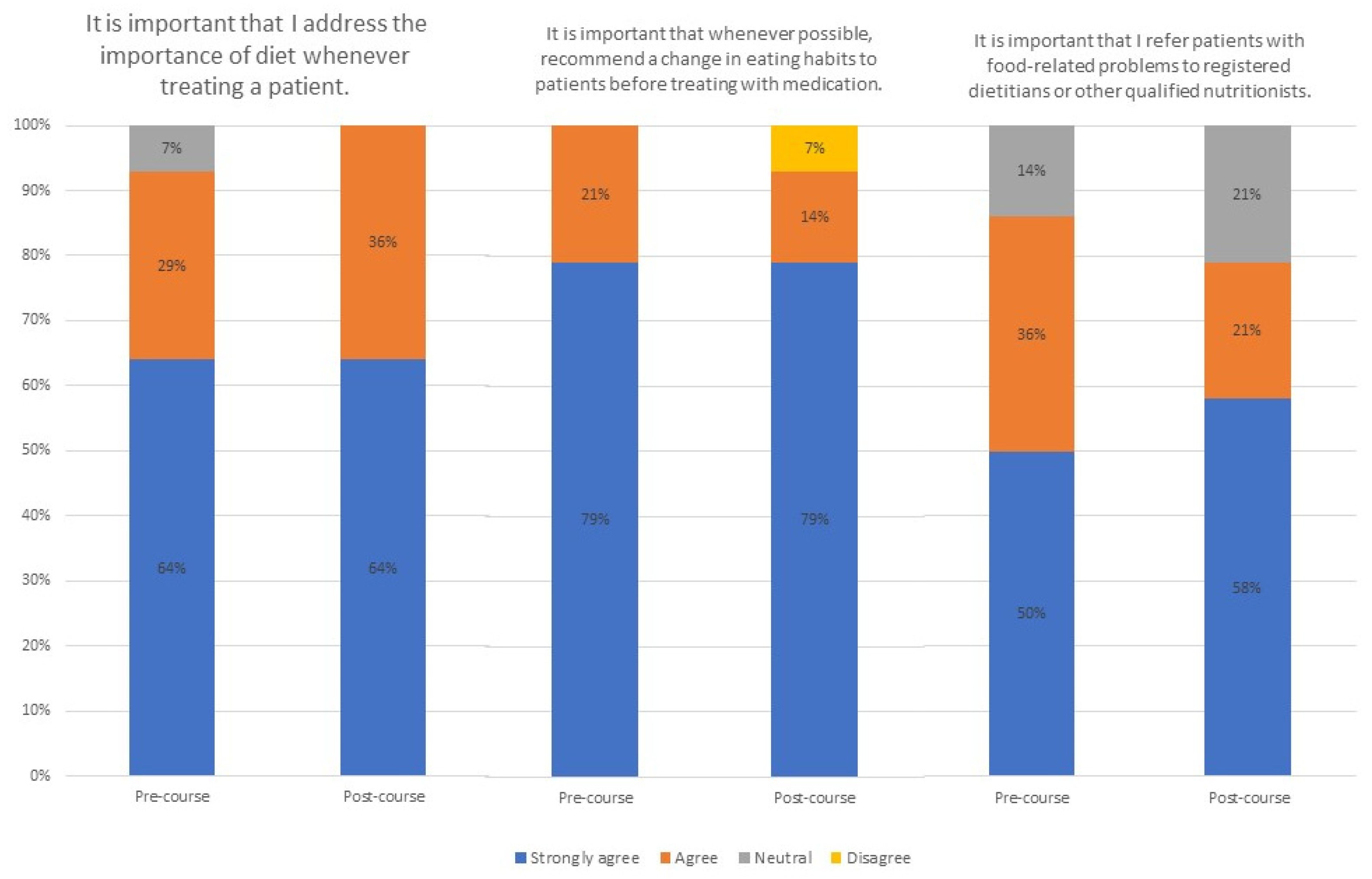

Figure 2). No relevant changes were found in the participants’ perceptions about the value of nutrition counseling. However, there was a noticeable improvement in the endorsement of dietary habit changes before resorting to medication and a slight rise in the likelihood of referring patients to registered dietitians or other qualified nutritionist, increasing from 50% to 58% of the participants strongly agreeing with this statement, after completing the course (

Figure 3).

Food Management Skills: Participants showed notable improvements in various aspects in food management, such as using a shopping list, buying seasonal products, understanding, and using nutritional information, preparing meals in advance, and efficiently using leftovers. Despite these positive developments, statistical significance could not be firmly established (

Table 4).

Culinary skills: Participants indicated marked improvements in their self-perception about certain cooking techniques like steaming; improving from the mean punctuation going from 4.79 (SD=2.26) to 5.93 (SD=1.86), frying; increasing from 3.43 (SD=2.38) to 4.64 (SD=2.35), and microwave cooking; mounting from 3.71 (SD=2.76) to 4.64 (SD=2.21) (p<0.05) (

Table 5).

Counseling Confidence: There was an increase in confidence across all items, with a statistically significant improvement noted in confidence regarding personal culinary skills raising from 4.21 (SD=1.76) to 5.29 (SD=1.68) (p<0.001) (

Table 6).

Qualitative analysis: Remarkably, on the responses to open-ended questions in the survey, only one participant reported not having changed his/her attitude following the course. The remaining participants indicated that the course had enriched their knowledge, particularly in helping patients to modify their dietary habits. When asked about integrating the skills acquired from the course into their professional practice with patients, the responses were consistent: Participants reported that the application of these skills was straight forward, emphasizing that they could now provide more effective information to assist patients in adopting healthier habits. Moreover, we inquired about the most impactful aspect of the course, which was the value of hands-on practice in learning new culinary skills. Finally, The last open-ended question was related to some aspects we could improve. Most answers were related to the extension of the course (

Table 7,

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

As per our knowledge, at the time of the study, no scientific articles were identified that specifically explored hands-on culinary medicine education for healthcare professionals. To fill this gap, a mixed-methods pilot implementation program was designed and implemented, engaging healthcare professionals which encompassed a series of interactive, hands-on sessions that merged the know-how of experts’ gastronomy, food management, culinary skills, and culinary diet therapy, with a specific focus on prevalent diseases and their prevention, treatment, and care. The ultimate goal of this intervention was to evaluate the impact of participation in a CM program on Mediterranean diet adherence, food management skills, culinary proficiency, and counseling confidence among HCPs.

Our findings align with other parallel online interventions [

17,

18]. After the completion of the course, there was a noticeable increase in adherence to the Mediterranean diet, which was associated with increased confidence levels and culinary skills [

19].

After completing the course, a reduced number of professionals concurred that dietary advice lacks efficacy given the time constraints faced by professionals, possibly indicating a belief that even with limited time, effective communication can lead to meaningful patient behavior change. In this sense, the course also helped them consider that it is worth counseling patients with poor eating habits. Although before and after the course the vast majority of participants considered that dispensing dietary advice should constitute a routine aspect of all physicians' care, after the course a few of them sowed neutral response, likely reflecting a belief that this task requires specific training, and this responsibility falls within the purview of registered dietitians. No investigations were identified that delved into these particular facets, boosting our interest to assess the consolidation this results in studies of higher depth. On the other hand, our intervention demonstrated a perceived augmentation in understanding of food and diet therapy that was indeed in line with other results from similar studies [

20,

21,

22].

Participants showed notable improvements in various aspects in food management skills such as cooking healthy meals with few ingredients and culinary skills like microwave cooking and using herbs and spices. Other changes in dietary habits may occur more slowly in the months after the course and therefore may not be captured in the immediate post-pilot surveys. Beyond that, as there is also a growing body of literature supporting the fact that when physicians consolidate healthy lifestyle choices in their personal lives, they are much more likely to promote these choices to their patients [

23,

24,

25], we reckon that our findings have a clear potential for potentially improving patient care.

Our findings align consistently with the outcomes observed in other studies assessing the impact of CM courses on medical students where targeted educational initiatives have been shown to be effective in developing practical cooking skills with the goal of expanding nutritional knowledge and promoting the effective preparation of diverse food groups in order to optimize cooking times [

17,

18].

An investigation conducted on the Australian population through a cross-sectional study delved into the perceived barriers and advantages associated with plant-based foods, encompassing vegetables, cereals, pulses, nuts, and seeds. Their findings underscored that, participants regarded the incorporation of pulses into their diet as challenging, citing issues such as taste, perceived time-intensive preparation, and a lack of knowledge regarding palatable cooking recipes [

26]. These results serve as an example to emphasize the importance of -autonomous- meal preparation to reduce reliance on ready-to eat and processed foods, and how this should be an important aspect to consider when HCPs give nutritional advice and, consequently, when receiving nutritional education to do so. Convergently, other studies have consistently shown strong correlations between proficiency in healthy food preparation skills and improved dietary quality [

27], as well as between time spent cooking and mortality [

28]. Besides, in alignment with the results on the Australian cohort, a comprehensive review in 2015 reported practical tools aimed both professionals and patients to facilitate the integration of legumes into cooking practices and enhance overall eating habits [

29].

In the light of these results, our holistic educational approach could also contribute to the creation of nutritionally balanced yet appealing dishes, thereby serving as an effective strategy to encourage the adoption of healthy eating habits, as HCPs have the capacity to impart knowledge, tools, and attitudes that empower individuals to develop the skills necessary for behavioral change, as studies have demonstrated how HCPs who have undergone culinary and nutritional courses have demonstrated heightened confidence in advising patients on maintaining a healthy diet [

8,

30,

31], as also seen in the results from our PIP.

Findings described in the literature also support our proposed potential correlation between non-specialized HCP with better culinary skills and better dietary and nutritional advice during their clinical practice. Dietary counseling has been described to encompass a skill set that comprises proficiencies in assessment, communication style, implementation, and background knowledge [

32]. Practical, hands-on instruction in cooking and nutrition has been proven to be more efficacious in enhancing the dietary habits of professionals compared to traditional clinical nutrition education [

31,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Moreover, present research also underscores the correlation between the personal health practices of medical students and their subsequent patient counseling practices [

25,

37,

38,

39,

40] and the significance of healthcare providers actively engaging in their own health behaviors as a fundamental component in augmenting patient adherence to healthier lifestyles and overall experience, as shown in other studies [

5,

6,

8,

9,

10].

As described in the methods sections, this study has limitations bound to being a PIP, and also others identified in other CM studies, starting with the vague definition that is often pinned to the concept of “culinary medicine”. While this term has a recognized definition in academic literature, there is a noticeable absence of standardized guidelines specifying the content, duration, delivery methods, structure, or educational goal of associated programs [

41]. This gap raises questions about the extent to which this standardized definition is universally understood and whether HCPs share a consistent interpretation when using this term. The lack of standardization approach in CM’s methodology could imply that the health benefits often attributed to CM may not be as substantial or consistent as previously reported. Moreover, lack of a control group in our PIP design limits our ability to establish a benchmark for assessing changes in knowledge or attitudes resulting from the program. The gender distribution of participants presents another limitation, with a predominant female presentation and only two male participants. This imbalance could affect the applicability of our findings across genders. Furthermore, the professional background of the majority of participants was in nursing. This concentration in one field reduces diversity of healthcare perspectives and may limit the extrapolation of our findings to other healthcare disciplines.

For future assessment, there is a crucial need for more robust study designs to overcome the PIP-related limitations, including the use of control groups, to strengthen the reliability of findings. In our following explorations, recruitment strategies will be refined to mitigate sampling biases, and the implementation of standard, valid and reliable data collection instruments will be established. An initial assessment of culinary skills tailored to individual participants will lead to more personalized and effective training programs. Moreover, future interventions will also target potentially underrepresented socio-demographics straits, to ensure a more inclusive understanding of the benefits of CM training.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our findings highlight the vital role of CM training as an integral component of nutrition education for HCPs. Our PIP demonstrated its potential to positively influence attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors related to healthy cooking and eating for HCPs. To fully appreciate the public health benefits of CM training and its impact on HCPs, further research with larger, more diverse samples is essential. This pilot study lays the groundwork for future exploration in the field of culinary medicine, indicating its value contribution to the broader context of health and wellness. With refined methodologies and expanded research efforts, the full potential of CM training can be realized, ultimately enhancing healthcare delivery and patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

L.A., I.P.G., and V.M. equally contributed to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Di Daniele, N. The Role of Preventive Nutrition in Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Aldaz, D.; Cucalon, G.; Ordonez, C. Food insecurity as a risk factor for obesity: A review. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 1012734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, B.A.; Mokdad, A.H. Addressing Nutrition and Chronic Disease: Past, Present, and Future Research Directions. Food Nutr Bull. 2020, 41, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Puma, J. What Is Culinary Medicine and What Does It Do? Popul Health Manag. 2016, 19, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicks, M.; Trofholz, A.C.; Stang, J.S.; Laska, M.N. Impact of cooking and home food preparation interventions among adults: outcomes and implications for future programs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014, 46, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicks, M.; Kocher, M.; Reeder, J. Impact of Cooking and Home Food Preparation Interventions Among Adults: A Systematic Review (2011-2016). J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018, 50, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irl, B.H.; Evert, A.; Fleming, A.; Gaudiani, L.M.; Guggenmos, K.J.; Kaufer, D.I.; McGill, J.B.; Verderese, C.A.; Martinez, J. Culinary Medicine: Advancing a Framework for Healthier Eating to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Prevention. Clin Ther. 2019, 41, 2184–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, J.M.; Bilici, N.; Mergler, B.; Schumacher, R.; Mataraza-Desmond, T.; Booth, M.; Olshan, M.; Bailey, M.; Mascarenhas, M.; Duffy, W.; Virudachalam, S.; DeLisser, H.M. A Culinary Medicine Elective for Clinically Experienced Medical Students: A Pilot Study. J Altern Complement Med. 2020, 26, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayón-Orea, C.; Razquin, C.; Bulló, M.; Corella, D.; Fitó, M.; Romaguera, D.; Vioque, J.; Alonso-Gómez, Á.M.; Wärnberg, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Serra-Majem, L.; Estruch, R.; Tinahones, F.J.; Lapetra, J.; Pintó, X.; Tur, J.A.; López-Miranda, J.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Matía-Martín, P.; Daimiel, L.; Sánchez, V.M.; Vidal, J.; Vázquez, C.; Ros, E.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Sorlí, J.V.; Castañer, O.; Fiol, M.; Navarrete-Muñoz, E.M.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Zulet, M.A.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Casas, R.; Bernal-López, R.; Santos-Lozano, J.M.; Corbella, E.; Bouzas, C.; García-Arellano, A.; Basora, J.; Asensio, E.M.; Schröder, H.; Moñino, M.; García de la Hera, M.; Tojal-Sierra, L.; Toledo, E.; Díaz-López, A.; Goday, A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Martínez-González, M.A. Effect of a Nutritional and Behavioral Intervention on Energy-Reduced Mediterranean Diet Adherence Among Patients With Metabolic Syndrome: Interim Analysis of the PREDIMED-Plus Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019, 322, 1486–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozica-Olenski, S.; Treleaven, E.; Hewitt, M.; McRae, P.; Young, A.; Walsh, Z.; Mudge, A. Patient-reported experiences of mealtime care and food access in acute and rehabilitation hospital settings: a cross-sectional survey. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2021, 34, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritlove, C.; Capone, G.; Kita, H.; Gladman, S.; Maganti, M.; Jones, J.M. Cooking for Vitality: Pilot Study of an Innovative Culinary Nutrition Intervention for Cancer-Related Fatigue in Cancer Survivors. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Recommended Dietary Allowances: 10th Edition; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010, 363, 2477–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massanés T. (22 Sept 2019). ¿Es comer bien una cosa de ricos?. La Vanguardia. https://www.lavanguardia.com/comer/opinion/20190922/47500133505/comer-bien-lujo-producto-ricos-toni-massanes.html.

- Massanés T. (06 Oct 2019). Sentido común para que el mundo siga girando. La Vanguardia. https://www.lavanguardia.com/comer/opinion/20191006/47799102601/sentido-comun-cienciaalimentaria-carne-procesada-despilfarro-alimentario-cambio-climatico.html.

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; Vinyoles, E.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Lahoz, C.; Serra-Majem, L.; Pintó, X.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.; Covas, M.I. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfert, M.D.; Wattick, R.A.; Hagedorn, R.L. Experiential Application of a Culinary Medicine Cultural Immersion Program for Health Professionals. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020, 7, 2382120520927396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, A.C.; Latoff, A.; Dyer, A.; Albin, J.L.; Artz, K.; Babcock, A.; Cimino, F.; Daghigh, F.; Dollinger, B.; Fiellin, M.; Johnston, E.A.; Jones, G.M.; Karch, R.D.; Keller, E.T.; Nace, H.; Parekh, N.K.; Petrosky, S.N.; Robinson, A.; Rosen, J.; Sheridan, E.M.; Warner, S.W.; Willis, J.L.; Harlan, T.S. Virtual teaching kitchen classes and cardiovascular disease prevention counselling among medical trainees. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. 2023, 6, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalán, Àlex MD; Gastaldo, Isabella MSc; Roura, Elena PhD, RD; Massanes, Toni; Escarrabill, Joan PhD, MD; Moizé, Violeta PhD, RD. Influence of Nutrition Training, Eating Habits, and Culinary Skills of Health Care Professionals and Its Impact in the Promotion of Healthy Eating Habits. Topics in Clinical Nutrition 2023, 38, 66-76. [CrossRef]

- Hashimi, H.; Boggs, K.; Harada, C.N. Cooking demonstrations to teach nutrition counseling and social determinants of health. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2020, 33, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, B.; Memel, Z.; Diamant, C.; Clarke, E.; Chou, S.; Gregory, H. Culinary medicine and community partnership: hands-on culinary skills training to empower medical students to provide patient-centered nutrition education. Med Educ Online. 2019, 24, 1630238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, N.I.; Gleit, R.D.; Levine, D.L. Culinary nutrition course equips future physicians to educate patients on a healthy diet: an interventional pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2021, 21, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, E.; Breyan, J.; Elon, L. Physician disclosure of healthy personal behaviors improves credibility and ability to motivate. Arch. Fam. Med. 2000, 9, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer EH, Frank E, Elon LK, et al. Predictors of nutrition counseling behaviors and attitudes in US medical students. Am J Clin Nutr 2006, 84, 655–662. [CrossRef]

- Oberg, E.B.; Frank, E. Physicians’ health practices strongly influence patient health practices. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2009, 39, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueira, N.; Curtain, F.; Beck, E.; Grafenauer, S. Consumer Understanding and Culinary Use of Legumes in Australia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, N.I.; Perry, C.L.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Food preparation by young adults is associated with better diet quality. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 2001–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.C.; Lee, M.S.; Chang, Y.H.; Wahlqvist, M.L. Cooking frequency may enhance survival in Taiwanese elderly. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, R.; Phillips, E.M.; Campbell, A. Legumes: Health Benefits and Culinary Approaches to Increase Intake. Clin. Diabetes 2015, 33, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandon Pang, Zoe Memel, Carmel Diamant, Emily Clarke, Sherene Chou & Gregory Harlan (2019) Culinary medicine and community partnership: hands-on culinary skills training to empower medical students to provide patient-centered nutrition education, Medical Education Online, 24:1, 1630238. [CrossRef]

- Razavi, A.C.; Monlezun, D.J.; Sapin, A.; Stauber, Z.; Schradle, K.; Schlag, E.; Dyer, A.; Gagen, B.; McCormack, I.G.; Akhiwu, O.; et al. Multisite culinary medicine curriculum is associated with cardioprotective dietary patterns and lifestyle medicine competencies among medical trainees. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 14, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, B.R.; Beals, K.A.; Burns, R.D.; Chow, C.J.; Locke, A.B.; Petzold, M.P.; Dvorak, T.E. Impact of Culinary Medicine Course on Confidence and Competence in Diet and Lifestyle Counseling, Interprofessional Communication, and Health Behaviors and Advocacy. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monlezun, D.J.; Dart, L.; Vanbeber, A.; Smith-Barbaro, P.; Costilla, V.; Samuel, C.; Terregino, C.A.; Abali, E.E.; Dollinger, B.; Baumgartner, N.; et al. Machine learning-augmented propensity score-adjusted multilevel mixed effects panel analysis of hands-on cooking and nutrition education versus traditional curriculum for medical students as preventive cardiology: Multisite cohort study of 3,248 trainees over 5 years. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5051289. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, M.; Cheung, E.; Mahadevan, R.; Folkens, S.; Edens, N. Cooking up health: A novel culinary medicine and service learning elective for health professional students. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2019, 25, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monlezun, D.J.; Leong, B.; Joo, E.; Birkhead, A.G.; Sarris, L.; Harlan, T.S. Novel longitudinal and propensity score matched analysis of hands-on cooking and nutrition education versus traditional clinical education among 627 medical students. Adv. Prev. Med. 2015, 2015, 656780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallanes, E.; Sen, A.; Siler, M.; Albin, J. Nutrition from the kitchen: Culinary medicine impacts students’ counseling confidence. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.; Carrera, J.S.; Elon, L.; Hertzberg, V.S. Predictors of US medical students’ prevention counseling practices. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, E.; Rothenberg, R.; Lewis, C.; Belodoff, B.F. Correlates of physicians’ prevention-related practices. Findings from the Women Physicians’ Health Study. Arch. Fam. Med. 2000, 9, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobelo, F.; Duperly, J.; Frank, E. Physical activity habits of doctors and medical students influence their counselling practices. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, S.; Stein, J.; Schaufele, M.; Frates, E.; Rogan, S. Personal exercise habits and counseling practices of primary care physicians: A national survey. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 2000, 10, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, R.; Phillips, E.M.; Nordgren, J.; La Puma, J.; La Barba, J.; Cucuzzella, M.; Graham, R.; Harlan, T.S.; Burg, T.; Eisenberg, D. Health-related Culinary Education: A Summary of Representative Emerging Programs for Health Professionals and Patients. Glob Adv Health Med. 2016, 5, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).