You are currently viewing a beta version of our website. If you spot anything unusual, kindly let us know.

Preprint

Article

Exploring the Quality Statuses of Graduates’ Sustainable Core Competences Development and the Reasons behind the Identified Statuses in Universities: Applying the Core Competencies’ Model and Major Stakeholders’ Perspectives

Altmetrics

Downloads

136

Views

65

Comments

0

This version is not peer-reviewed

Abstract

This study aimed at investigating the quality statuses of graduates’ sustainable core competences development and the causes behind the identified competence statuses by applying the core competencies’ model. The study employed case study design with thematic analysis involving seven interviewees. This study used tracer study findings and national exit exam results as exhibits. The study revealed “very good” and “excellent” quality statuses for the graduates’ core competence development of College of medicine and Health Sciences (CMHS). Similarly, this study identified “Good +” statuses for the quality of graduates’ core competence development in College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences ( CAES) and College of Science (CS). Furthermore, the study identified "good" - and +” statuses for the quality of graduates’ competence development at the Faculty of Social Sciences (FSS) and Faculty of Humanities (FH). Improved instruction with a balance of theory and practice, task-oriented deans’ leadership behavior with fairness and shared vision- mission identity, handling internal conflicts, and external ethnic-based war influences were the major reasons for the identified higher competence quality statuses in CMHS, CAES, and CS, whereas the opposite direction decline of these factors were the causes for the low statuses of FSS and FH. Sustainable graduates’ core competence development leads to sustainable employability, labor force, and individual to nation-wide holistic sustainable development

Keywords:

Subject: Social Sciences - Education

1. Introduction

Tomorrow's qualified work forces are determined by the current quality of graduates’ core competences domain development in HEIs, which again play a vital role in the educational, environmental, social, and economic aspects of the sustainable development of a nation (Demeter, Jele, & Major, 2022; Rojas & Rojas, 2016). Such qualified workforces are also responsible for conducting research projects and utilizing them for the initiation and better implementation of change initiatives, as well as improving policy making and implementation for achieving the aforementioned national sustainable developments (Demeter, Jele, & Major, 2022; Ciraso-Cali et al., 2022). Therefore, the quality of graduates’ competence development in today's HEIs is a determinant issue for overall national sustainable development (Tekeste, 1990; Tekeste, 1996; MoE, 2018; Zhou, 2016).

However, the quality of graduates’ competence development in developed and developing countries deferred so much (Demeter et al., 2022) that in developing countries like Ethiopian universities, there are several conditions that cause undesired quality of qualified work force who have also direct negative impact on economic, educational, socio-cultural, and environmental sustainable developments (Nikusekela & Pallangyo, 2016). Specifically in Bahir Dar university, Kerebih et al (2020) conducted a tracer study of 2016/17 and 2017/18 cohort graduates to investigate the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in various domains of competences such as field specific subject matter knowledge, generic knowledge, research, problem solving, teamwork, time management, report writing, ICT and project management) using structured questionnaire and analyzed following quantitative design and analysis and found that, 72% grand score for all domains of core competencies indicating the graduates are at the lower limit of “very good” status of quality of graduates’ competence development. 74% graduates were employed. And they found 60% employers’ satisfaction on graduates’ competence development qualities which were applied in their job task accomplishment and institutional goal achievement. They conducted this study without addressing the reasons behind the identified statuses and they did not apply qualitative data analysis.

Likewise, Haile et al. (2019) also conducted a tracer study of the 2015/2016 cohort of graduating class students to scrutinize the graduates’ employment status using a questionnaire and quantitative design and analysis model and found out that 79% of graduates were employed, and 93% of graduates were employed in field-related occupations or jobs, without determining the graduates’ competence quality status, the reasons for the identified employment gaps, or qualitative data analysis.

The above two studies also lack university academics perspective data and analysis, which were considered as limitations. These two tracer studies were relatively more advanced and comprehensive than all other tracer studies conducted in BDU in recent decades.

Therefore, the current study addressed the above two tracer studies’ limitations that are determining the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development, the reasons behind the identified statuses, applying different design and analysis approaches, and involving academics’ perspective data, which were all different from the tracer studies. The current study is also more focused on university academics, employers, and graduates themselves perspectives on graduates’ quality status determination and the major reasons for the identified statuses, in addition to the tracer study and university exit exam result exhibits involved to make the study in-depth and comprehensive.

Moreover, many Ethiopian university graduates stayed unemployed for a long time, especially in recent decades (Semela, 2011; Haile, Zeleke, Petros, Sifelig, & Aragaw, 2019), and if they got the career opportunity, the employers’ satisfaction with them was moderate (60%). Kerebih (2020). These implies that competence gaps appeared between university graduates’ competence development and the career competence requirements of employers for the specific occupations and jobs (Dunne, Bennett, & Carré, 2000; QCA, 2001).

Accordingly to the employment requirements made by HRM experts, both government and non-governmental organizations can hire employees relying on the regulations with fairness and transparency so that these employees are expected to accomplish tasks well and achieve goals, then contribute to the nations’ holistic developments, which are also vital for the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) (Abelha, Fernandes, Mesquita, & Ferreira-Oliveira, 2020; Zhou, 2016).

However, in developing countries like Ethiopia, such nation developments are minimal due to the fact that many indicators such as (poverty, antisocial behaviours, poor health, poor education, insecurity, and other risk issues in the nation disclose the presence of a poor quality workforce, lower performance, and underdevelopment as outcomes, symptoms, and ill effects of the existing universities in producing constructive, pro-social, collaborative, innovative, and problem-solving graduates in the country.

Moreover, the incidences of over-education and under-education qualification mismatches or matched employments can appear in terms of the qualification level demanded by the job and actually achieved qualifications by the employees. But, in all three employment incidences, underskilling (undercompetence) can appear, and currently, in developing countries like Ethiopia, it is a problem in many civil service organisations (Kerebih et al., 2020; McGuinness, Pouliakas, & Redmond, 2017). Indeed, the majority of these employees were university graduates who indicated skill mismatches on one side due to graduates’ competence development (skill) gap on the other side due to employers’ inadequate hiring.

Therefore, identifying the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development using various stakeholders’ perspectives and investigating the major causes for such identified gaps were the aims of this study in general.

Having in mind the above aims, this study attempted to answer the following basic research questions:

RQ1. How academics, employers and the graduates themselves do perceived the quality statuses of graduates’ core competence domains development using personal or public point of reference in their respective colleges for the last 6 years at BDU?

RQ2. What did the tracer study finding and exit exam result exhibits entail about the quality statuses of graduates’ core competence domain development at BDU?

RQ3. What was/were the major causes for the identified quality statuses of graduates’ core competences domain development may be in favor or against the normative public/personal point of reference?

2. Review of Related Literature and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptualization of Graduates’ Competence Development

In university contexts, employability is conceptualized as more than simply obtaining a career. Harvey (2003), because it infers various attainments—skills, cognitions, and personal qualities—that enable graduates to be successful in attaining desired career employments, which benefit themselves, the labour force, the nation, and the national or global economy (Yorke, 2006). This perspective supports the notion that the concept of employability involves competence in different dimensions (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert, 2019). The focus is on the identification and development of knowledge, skills, and attributes that enhance students’ active competence for performance improvement in the labour force. This perspective also reinforces the responsibility of universities in sustaining the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development actually acquired by their graduates.

Many studies perceive the concept of competence from different perspectives and using different words, such as abilities, knowledge, and skills (Hoffmann, 1999). This idea is reinforced by Ashworth and Saxton (1990), who state that ‘it is not clear whether competence is a personal attribute, an act, or an outcome of action’ (p. 3). Thus, competence is a problematic concept (Westera, 2001). This discussion is not new, but it is necessary when inquiring about the concept of competences in the context of universities. This is the reason behind the strong relationships between competence and employability concepts in many investigations.

Having this in mind, scholars worldwide provide a broad perspective definition for the concept of competence and graduates’ competence development, following five main conceptual dimensions as follows: (1) Competence refers to people who have the quality or state of being functionally adequate or of having sufficient knowledge, judgment, skill, or strength for doing a particular duty based on previous background (knowledge, skills, abilities, past experiences, beliefs, values, etc.) (Webster, 2000). (2) Competence implies the mobilization of those resources (knowledge, skills, and dispositional values) in a specific context (e.g., solving a problem) (Webster, 2000). (3) Competence is visible within a particular context in which it is possible to identify which competences people need to develop (Stoof, Martens, Van Merrien Boer, & Bastiaens, 2002). (4) Competence requires more than the acquisition of knowledge. It is also more than a skill; it is something that a person is able to do (Rychen & Salganik, 2003). (5) Competence is a complex term, and some authors organize it into categories to provide a greater understanding of methodological issues (Wittorski, 2012). For instance, the graduates' knowledge, skills, and grit or perseverance skills are the main components of graduate competence development.

Graduates’ competence development fits with the occupational position competence requirement if the university graduates have acquired the necessary knowledge, skills, and values that enable the individual to do all or the majority of tasks in the required job so that production function is enhanced at the desired personal, institutional, or public standard point of reference. Qualification level fit with occupational position (job) qualification requirement is also the usually adopted match, especially for the recruitment process or purpose (McGuinness, Pouliakas, & Redmond, 2017). On the other hand, graduates’ competence mismatch with occupational competence in the form of vertical mismatch (usually measured in terms of over-education, under-education, over-skilling, and under-skilling), competence gaps, competence shortages (usually measured in terms of unfilled and hard-to-fill vacancies), field of study and position or job type difference (horizontal) mismatch, and skill obsolescence due to dynamic changes occurring in time that the new thought replaces the old (McGuinness, Pouliakas, & Redmond, 2017; Abelha et al., 2020).

2.2. Theoretical Framework

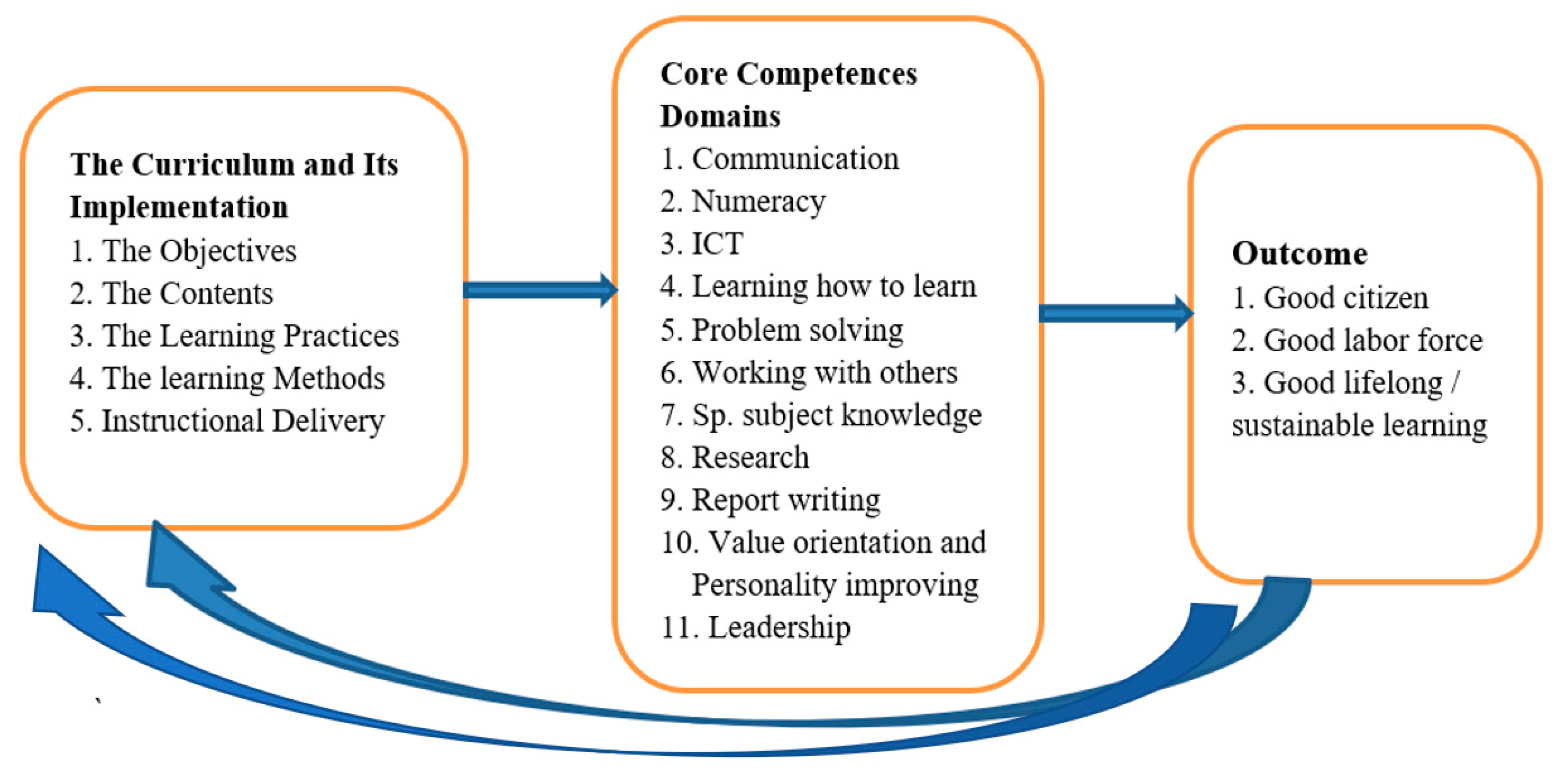

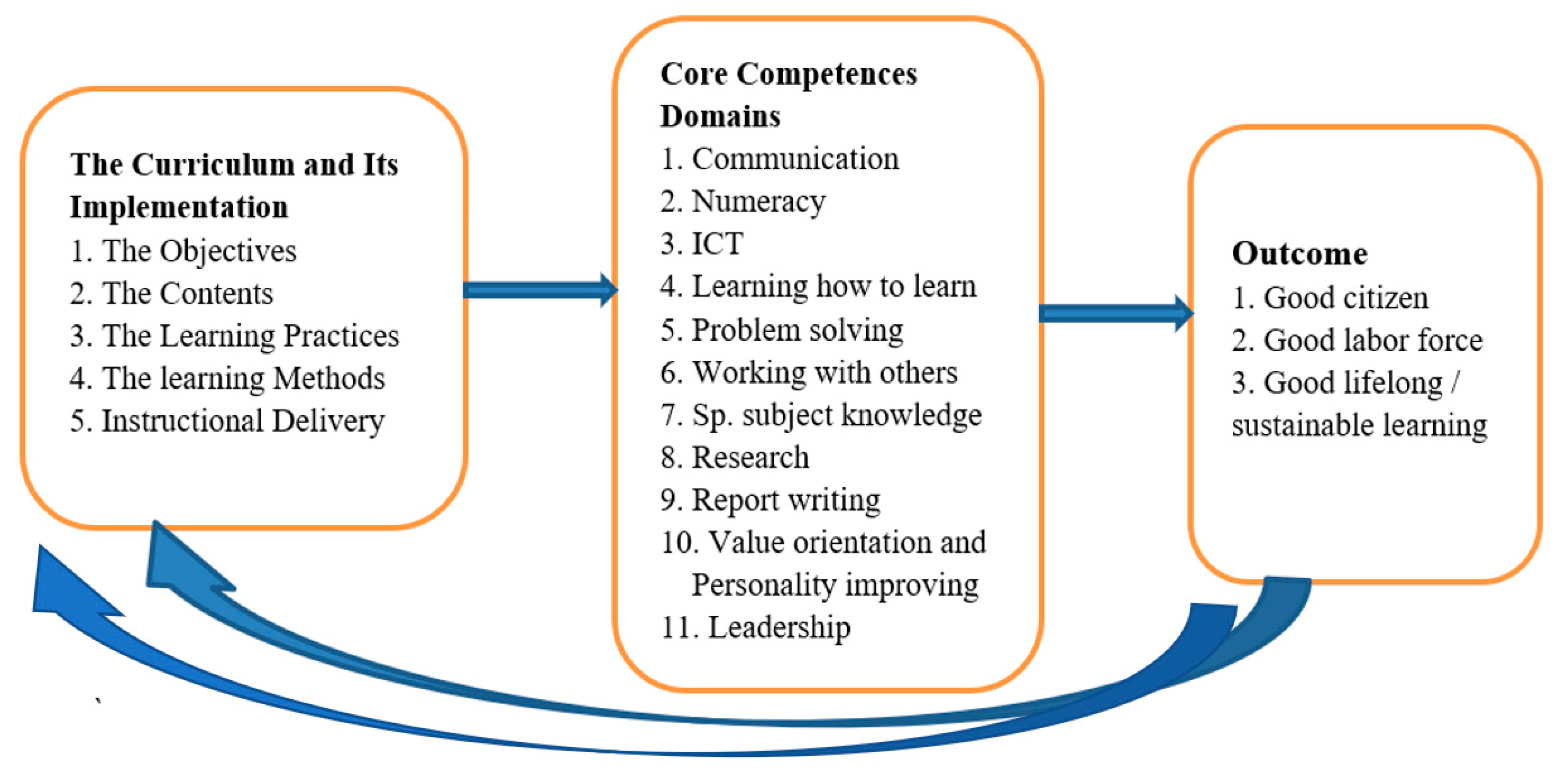

This study specifically built on the core competencies model adapted from Dunne, Bennet & Carre (2000); QCA (2002); Washer (2007); Hadiyanto (2010) and Kerebih et al. (2020) which it focuses on the curriculum, domains of graduates’ core competences and the outcome of core competencies.

2.2.1. The Curriculum and Its Implementation in Universities Match with Core Competencies

The curriculum and its implementation are important input factors for graduates' core competency development. The curriculum is the planned and structured set of learning outcomes, content, and activities that guide the teaching and learning process (CRSC, 2004; Hadiyanto, 2010). ⁷. Implementation is the actual delivery and enactment of the curriculum in the classroom and beyond. Both the curriculum and the implementation should be aligned with the core competencies that the university aims to foster in its students (European Commission, 2018; Hadiyanto, 2010).

One way to achieve this alignment is to adopt a competency-based curriculum, which is a curriculum that emphasizes what learners are expected to do rather than mainly focusing on what they are expected to know (Dunne, Bennett, & Carré, 2000; QCA, 2001). A competency-based curriculum defines the core competencies that students should acquire and demonstrate by the end of their studies and organizes the learning outcomes, content, and assessment around these competencies (Brauer, 2021; Zhang et al., 2023). This way, the curriculum becomes more relevant, flexible, and personalized to the needs and interests of the students and society.

In conclusion, the curriculum and its implementation are key input factors for graduates' core competency development. By adopting a competency-based curriculum and using pedagogical approaches that support the development of core competencies, universities can prepare their students for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century employability, good citizenship and sustainable learning and change adaptation (Zhang et al., 2023; Hadiyanto, 2010; Abelha, 2020).

2.2.2. Graduates’ Core Competencies Description

- Communication Skills: The skill that allows graduates to convey their idea as an individual or as a group member and to include a variety of backgrounds in order to reach a good decision, solution, and negotiation (Chauhan, Begum & Saiyad, 2023)). Communication skills mean one’s ability to apply active listening, writing skills, oral communication, presentation skills, questioning, and feedback skills to achieve effective communication (QCA, 2002; SQA, 2003; Washer, 2007; and Jones, 2009).

- Numeracy: Numeracy is one of the core competence domains that are essential for conducting clinical research. Numeracy refers to the ability to use and understand numbers, data, and mathematical concepts in various contexts and situations (Washer, 2007; Zalizan Mohammad Jelas et al., 2006). Numeracy skills include calculating, interpreting, analyzing, and presenting quantitative information. Numeracy is important for designing, conducting, and evaluating clinical trials, as well as for communicating the results and implications of the research. Numeracy can also help researchers critically appraise the quality and validity of existing evidence and apply it to their own practice (Washer, 2007).

- Information Technology: Information technology is one of the core competence domains that are essential for many professions and fields of study. Information technology refers to the use and development of computer systems, software, networks, and devices to create, store, process, and communicate information. Information technology skills include the ability to use various hardware and software tools, such as operating systems, applications, databases, programming languages, web design, cyber-security, and cloud computing (SQA, 2003; Washer, 2007). Information technology is important for enhancing productivity, efficiency, innovation, and collaboration in various domains and contexts. Information technology can also help professionals and learners to access, analyze, and evaluate information from various sources and to create and share knowledge (Hadiyanto, 2010).

- Learning how to learn: Learning how to learn is a core competence domain that involves the ability to seek, acquire, retain, and apply knowledge and skills in various contexts (Washer, 2007; Zalizan Mohammad Jelas et al., 2006). It is also the ability to understand how one learns best and to use effective strategies and techniques to enhance one’s own learning process. Learning how to learn can help one achieve personal, academic, and professional goals, as well as adapt to changing situations and challenges (European Commission, 2018; QCA, 2002).

- Problem Solving: Problem solving is a core competence domain that involves the ability of the individual, group, or nation to think in depth and perform well to achieve a goal by overcoming obstacles using various unusual strategies and techniques (QCA, 2002; SQA, 2003; Dunne,;Bennett, & Carre, 2000; Washer, 2007; Zalizan Mohamad Jelas et al., 2006). It is also the ability to analyze a problem, identify its cause, and evaluate and select the best solution. Problem solving is a frequent part of most activities, as humans exert control over their environment through solutions. Problem solving can be applied to simple personal tasks or complex issues in business and technical fields.

- Working with Others: Working with Others is a core competence domain that involves the ability to effectively interact, cooperate, collaborate, and manage conflicts with other people in order to complete tasks and achieve shared goals (QCA, 2002; Washer, 2007; Zalizan Mohammad Jelas et al., 2006). It is also the ability to understand and work within a team or organization’s culture, rules, and values (QCA, 2002; SQA, 2003). Working with others requires many skills, such as communication, conflict management, consensus building, problem solving, decision-making, and respect for diversity.

- Subject-Specific Competencies: Subject-Specific Competencies is a core competence domain that involves the knowledge of theories, concepts, and techniques as well as their application to specific fields (Chauhan, Begum, & Saiyad, 2023). It is also the ability to demonstrate proficiency and excellence in one’s chosen subject area. Subject-specific competenciess are essential for academic and professional success, as they enable one to master the content and methods of a discipline, and contribute to its advancement (Washer, 2007)

-

Research Competence: Research competence is one of the core competence domains that are essential for conducting and disseminating high-quality research in any field (Ciraso-Calí et al., 2022). According to the European Commission, (2018), research competence is defined as "the ability to create new scientific and technological knowledge, products, processes, methods and systems, and to design and manage complex projects and research activities in a systematic and ethical manner" (Yu et al 2020). Research competence can be divided into seven sub-areas, each with its own set of learning outcomes and proficiency levels (Yu et al., 2020; Jamieson & Saunders, 2020). These are: (1) Cognitive abilities: the ability to apply critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving, and analytical skills to research problems; (2) Doing research: the ability to design, plan, implement, and evaluate research projects using appropriate methods, tools, and techniques. (3) Managing research: the ability to manage research activities, resources, data, and risks in compliance with ethical and legal standards and regulations. (4) Managing research tools: the ability to use and develop research tools, such as software, hardware, databases, and instruments, to support research processes and outputs; (5) Making an impact: the ability to communicate, disseminate, and exploit research results, and to foster innovation and social change through research. (6) Working with others: the ability to collaborate and network with other researchers, stakeholders, and users and to respect diversity and intercultural differences; (7) Self-management: the ability to manage one’s own professional development, learning, and well-being, and to cope with uncertainty and ambiguity in research.Research competence can be developed through various means, such as formal education, training, mentoring, and practice (Rao, 2013, Ciraso-Calí et al., 2022). Some examples of activities that can enhance research competence are: participating in research projects, workshops, seminars, and conferences; Reading and reviewing scientific literature and publications; writing and publishing research papers, reports, and proposals; applying for research grants and funding; Engaging in peer review and feedback processes; developing and maintaining a research portfolio and a personal research plan; Seeking and providing guidance and support from and to other researchers; exploring and exploiting research opportunities and collaborations; using and creating research tools and platforms; Communicating and disseminating research findings and implications to various audiences and media; Translating and applying research knowledge and skills to real-world problems and contexts.

-

Report writing skills: Report writing skills are one of the core competence domains that are essential for creating and presenting high-quality reports in any field. Report writing skills are “abilities that help professionals write brief documents about a topic." These skills are applicable for several jobs that may require writing, editing, and researching(Cer, 2019; Kim, Yang, Reyes & Conner, 2021). To write an effective report, one should identify the readers, define the scope, craft a thesis statement, group information logically, use headings, bullets, charts, photos, and other tools, write an enticing introduction and a compelling conclusion, and apply the rules of Standard English. The report should adhere to the specifications of the report brief analyze relevant information, structure material in a coherent order, present in a consistent manner, and draw appropriate conclusions.Report-writing skills can be divided into five sub-areas, each with its own set of learning outcomes and proficiency levels (Graham, & Alves, 2021). These are: (1) Research: the ability to find, evaluate, and use relevant and reliable sources and data to support the report topic and purpose. (2) Planning: the ability to organize the report content and structure and to create an outline and a timeline for the writing process. (3) Writing: the ability to communicate effectively with words, using clear and concise language, appropriate tone and style, and correct grammar and spelling. (4) Visual aids: the ability to use and create charts, tables, graphs, and other visual elements to illustrate and enhance the report content and message. (5) Editing and revising: the ability to review and improve the report draft, checking for accuracy, clarity, coherence, and consistency, and incorporating feedback from others.Report-writing skills can be developed through various means, such as formal education, training, mentoring, and practice. Some examples of activities that can enhance report-writing skills are: Reading and reviewing examples of reports from different fields and purposes Writing and publishing reports for different audiences and contexts, such as academic, professional, or personal. Applying for report writing grants and awards; participating in report writing competitions and challenges; Engaging in peer review and feedback processes, both as a reviewer and a writer; Seeking and providing guidance and support from and to other report writers, such as mentors, tutors, or colleagues; and Exploring and exploiting report writing opportunities and collaborations, such as online platforms, communities, or networks (Solomon et al., 2021; Chauhan, Begum & Saiyad, 2023).

-

Value-semantic orientation and personality improvement competence: Value-semantic and personality improvement competence is one of the core competence domains that is essential for developing and enhancing one’s personal values, meanings, and goals in life. According to Epanchintseva, Bukhtiyarova, & Panich (2021), value semantic and personality improvement competence is defined as "the ability to form and realize one’s own value-semantic orientations, to overcome value-semantic barriers and conflicts, to achieve personal growth and self-actualization."Value, semantics, and personality improvement competence can be divided into four sub-areas, each with its own set of learning outcomes and proficiency levels (Madin et al., 2022; Nikolenko et al., 2020). These are: (1) Value awareness: the ability to identify, understand, and appreciate one’s own and others’ values, beliefs, and motivations, and to recognize how they influence one’s behaviour and choices. (2) Value development: the ability to critically evaluate, revise, and create one’s own value system and to align one’s actions and goals with one’s values. (3) Value communication: the ability to express, share, and negotiate one’s values with others and to respect and tolerate different value perspectives and worldviews. (4) Value integration: the ability to integrate one’s values into one’s personality, identity, and life purpose and to achieve harmony and balance between one’s values and one’s environment.Value-semantic and personality-improvement competence can be developed through various means, such as formal education, training, mentoring, and practice. Some examples of activities that can enhance value-semantic and personality-improvement competence are: Reading and reflecting on philosophical, ethical, and spiritual texts and literature; Writing and presenting essays, speeches, and stories about one’s values and life experiences; Participating in value clarification and value education programmes and workshops; Engaging in self-assessment and feedback processes, such as personality tests, value inventories, and coaching sessions; Seeking and providing guidance and support from and to other value seekers, such as mentors, counsellors, or engineers, Exploring and exploiting value-added semantic and personality improvement opportunities and collaborations, such as online platforms, communities, or networks, Grit and perseverance, self-control, motivation and goal setting, and personal identity development are also part of this core competence domain.

-

Leadership competence: is one of the core competency domains for graduates’ competence development in universities. Leadership is the ability to guide, influence, and inspires others to accomplish tasks and achieve a common goal. Leadership competencies are the specific skills and attributes that make a graduate an effective leader (Kragt & Day, 2020). Some of the leadership competencies that are important for graduates to develop are: (1) Integrity: This is the quality of being honest, ethical, and consistent in one’s actions and decisions. Integrity helps leaders build trust and credibility with their followers, peers, and stakeholders. Leaders with integrity uphold the values and beliefs of their organization, admit their mistakes, and prioritize the well-being of others. (2) Self-discipline: This is the ability to control one’s emotions, impulses, and behaviors, and to overcome any personal challenges. Self-discipline helps leaders to focus on their goals, manage their time and energy, and commit to self-improvement. Leaders with self-discipline are aware of their strengths and areas for development and seek out feedback and opportunities to learn. The foundation on behalf of the entire set of leadership competencies is good self-leadership. (3) Empowerment: This is the ability to delegate authority and responsibility to others and to support them in achieving their potential. Empowerment helps leaders foster a culture of collaboration, innovation, and accountability. Leaders who empower others encourage them to self-organize, promote connection and belonging, and provide them with the resources and guidance they need. (4) Experimentation: This is the ability to embrace change, uncertainty, and ambiguity and to try new ideas and approaches. Experimentation helps leaders to adapt to the changing environment, solve problems creatively, and learn from failures. Leaders who experiment are open to feedback, willing to take risks, and committed to the professional and intellectual growth of themselves and others. (5)Teamwork: This is the ability to form and organize small supplementary and complimentary groups with delegating specified authority and responsibility for accomplishing the assigned tasks or innovative initiatives and achieving their goals that leads the organization or the nation towards competitiveness and success. Leaders need to have the skill of working with others while maintaining respect, dignity, transparency, participation, openness, and being people-oriented. (6) Project management: This is the ability of the leader to plan, organize, direct, staff, coordinate, review, and budget strategic initiatives with large or small-scale investments within the organization or nationwide. Risk-taking and handling various source conflicts in the process of project design, implementation, and evaluation of outcomes are also crucial competencies of leadership and project managers.Developing the eleven core competencies in the classroom and outside the classroom will help students become more effective and independent learners during their studies, as well as enhance their employment prospects upon graduation. As a result, the graduate of a university comes out with three major outcomes: employability, life-long learning, and good citizenship (QCA, 2002; Hadiyanto, 2006; Star & Hamer, 2007; Washer, 2007).

2.2.3. Desired Outcomes of the Model in the Nation and the World

Good citizenship and nation: Good citizenship is an outcome of the competence domains’ model, which is a framework that identifies the key competencies that citizens need to participate effectively in democratic societies. The competence domains’ model is based on the idea that citizenship is not only a legal status but also a set of desired skills, attitudes, values, and behaviors that enable individuals to contribute to the common good and to respect the rights and dignity of others. According to the European Commission (2018), good citizenship consists of four main domains: civic literacy, civic identity, civic agency, and civic virtue. (1) Civic literacy: the ability to acquire, understand, and use knowledge about the political and social systems, the history and culture, and the current issues and challenges of one’s own and other communities, countries, and regions. (2) Civic identity: the ability to develop and express a sense of belonging and commitment to one’s own and other groups, and to recognize and appreciate the diversity and interdependence of people and cultures. (3) Civic agency: the ability to act individually and collectively to address public issues and problems and to influence and shape the decisions and policies that affect one’s own and others’ lives. (4) Civic virtue: the ability to demonstrate ethical and moral reasoning, respect for human rights and dignity, and responsibility for the common good and the environment.

Good citizenship is the result of developing and applying these competencies in various contexts and situations, such as in the family, school, workplace, community, and online. Good citizens are not only informed and involved, but also respectful and responsible. They strive to do the right thing for their broader communities and for society and take an interest in working for the betterment of community and society (Mucinskas, Biller, Wajda, Gardner, & Yuen, 2023). Good citizens are also adaptable and resilient, able to cope with the challenges and opportunities of a changing and interconnected world.

Good labour force (human capital): A good labour force can be defined as an outcome of the core competencies model, which is a strategic tool that identifies the unique and important skills, knowledge, and behaviors that give an organization a sustainable competitive advantage (Hadiyanto, 2010; Zhou, 2016; Abelha et al., 2020; Ciraso-Cali et al., 2022). Therefore, a good labour force is one that has the capability and the motivation to use the core competencies of the organization to achieve superior performance and customer satisfaction (Zhou, 2016; Abelha et al., 2020).

Good lifelong learning culture: A good lifelong learning culture can be discussed as an outcome of the core competencies model, which is a strategic tool that identifies the unique and important skills, knowledge, and behaviors that give an organization a sustainable competitive advantage (González-Pérez & Ramírez-Montoya, 2022; Goodwill & Shen-Hsing, 2021).

According to the model, a good lifelong learning culture should have the following characteristics: It should foster the development of core competencies that are relevant to the organization’s goals and values and that are difficult for competitors to imitate or replicate (Hadiyanto, 2010). These core competencies should reflect the baseline behaviors and skills required by the organization, such as communication, teamwork, innovation, etc. (González-Pérez et al., 2022) It should encourage the application of core competencies to create unique and competitive products or services in the marketplace that meet the current and future needs of customers. These products or services should be aligned with the organization’s vision and mission and should provide value for money (González-Pérez, 2022). It should support the adaptation and learning of new skills and competencies as needed in response to the changing environment and customer demands. It should also facilitate the transfer and sharing of core competencies across different roles and functions within the organization and leverage them for continuous improvement and growth (González-Pérez et al., 2022).

Therefore, a good lifelong learning culture is one that enables and motivates the employees to use the core competencies of the organization to achieve superior performance and customer satisfaction and to acquire new competencies for personal and professional development. A good lifelong learning culture can also contribute to the outcome of the core competencies model by enhancing the organization’s ability to innovate and compete in the global market and by creating a positive and engaging work environment (González-Pérez et al., 2022; Goodwill & Shen-Hsing, 2021).

Figure 1.

Summary of the Graduates’ Core Competences Model. Source: Adapted from Hadiyanto, 2010; Kerebih et al., 2019.

Figure 1.

Summary of the Graduates’ Core Competences Model. Source: Adapted from Hadiyanto, 2010; Kerebih et al., 2019.

The model depicted the dynamic continuous interrelationship among the curriculum and its practice as vital input for developing sustainable graduates’ core competence domains which they in turn enhanced sustainable labor force that leads to sustainable holistic individual and nationwide developments which are also required for designing and investing on a quality curriculum and learning environments.

3. Design and Methods

3.1. Research Design

Qualitative research approach was used since this study explored the quality statuses of university graduates’ competence development using qualitative data and qualitative techniques. Qualitative research produces large amounts of contextually laden, subjective and rich details data (Byrne, 2001; Nugulube, Patrick, 2015). The researchers employed case study design as a guide for designing and conducting this study focusing on logical structure, plan and strategy (De Vaus, 2001, Croswell, 2014). Case study offers researchers an option to use information from many data sources.

3.2. Data Sources of the Study

Interviews, personal dialogues, researcher personal observations, tracer study finding exhibits, university exit exam result exhibits, and empirical evidence from literature reviews were required sources soliciting data for the study.

3.3. Sampling Techniques and Sample size determination

3.3.1. Interviewees

Five university academics, four graduates, two employers were Key informants consulted using purposive sampling technique on the assumption that they would provide me better data. Words, phrases, sentences, and articles of the interview transcript documents and informants were used as units of analysis to be involved in the analysis.

3.3.2. Tracer Study Finding Exhibits

The researchers used Kerebih et al. (2019) tracer study findings as exhibits to be analyzed integrated with other findings.

3.3.3. University Exit-Exam Result Exhibits

We used the 2022/23 cohort graduating class students’ national exit exam results as exhibits.

3.4. Instruments

3.4.1. Interviews

Evidences relevant to the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development from academics perspective RQ1, and the causes behind identified status RQ3, were collected using semi structured interviews with purposefully selected key informants. The researcher conducted 15 minutes interview with each individual academics and 10 minutes interview with graduating class student informants for each. Likewise, 20 minutes interview was carried out for each employer interviewee. For instance, “How do you judge the quality statuses of graduates’ core competence domain development in the last 6 years at BDU?” “What were the major reasons for the statuses you have identified?” …were some of the semi structured items.

3.4.2. Document Analysis

To gather reliable and valid data from the sample tracer study documents (i.e. 3 tracer study documents), the researcher used document analysis supported with coding sheet prepared to investigate the 2nd research basic question.

3.4.3. Exit exam results

Researchers used exit exam result data for the 2022/2023 cohort graduating class students as exhibit or demonstration to analyze its witness for the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in BDU for the last 6 years. This data was vital for scrutinizing RQ2.

3.5. Analysis Techniques

The data were analyzed using qualitative approach and design by organizing words, phrases, sentences and figures to represent desired facts, competences, and qualities for answering the RQs.

Content analysis, case study analysis and thematic analysis were the main analysis tools. Description of interview item to participants Quote participant responses prepare interview transcript interpret contextually discuss with literature and researcher ideas then suggest valid conclusion and recommendation were sequentially applied analysis frameworks in the study.

4. Findings

Based on the purpose and research questions of the study, this section presents the results collected through designed qualitative data gathering tools such as interviews, personal observation, documents, exhibits (tracer study findings, exit exam results).

4.1. Examining the Quality Statuses of Graduates’ Core Competences Domain Development

RQ1. How do stakeholders’ perceived statuses of graduates’ core competence domain development at BDU?

In the semi-structured interview, academics were asked to disclose their perception to the quality status of graduates’ competence development in their respective college for the last 5 years (2017 to 2022. Interviewees from CMHS, CAES, CS and FSS) reported in the same way judging moderately good to very good status of graduates’ competence development especially in terms of Production of competent graduates in knowledge of the discipline, affective behaviors, social relationships, time management and technological skills which can be considered as more pronounced outcomes for such status. In support of this finding, Ahmed in CS at BDU explained graduates competence development in his respective college saying:

The quality of graduates is generally very good except few graduates lack desired quality due to joining a department or college without their interest, background, area of ability and so on. Our college is very good in terms of instruction, using technology, laboratory and internship or practicum fieldworks. Of course, our deans showed less intervention in terms of deciding practicum field work sites or places comfortable to both students and instructors. The quality of graduates were also threatened in the last 5 years by the unsolved debates of the two colleges(CS and CEBSs) for owning responsibility and power to manage college of science teaching profession graduates (17 April 2022, 1:20).

From the findings of Ahmed, Y. we can argue that the respective universities prepared their students accordingly to public expectations or standards set by academics so that academics perceived the graduates’ core competence development as rationally sound and acceptable. This quality of graduates in the college was achieved through adequate synergy of the respective college deans, academics and students in the entire production function so that the already identified success was observable in the real ground as also confirmed by the graduates’ exit exam result exhibit analysis in this study. As reported by Ahmed Y., academics handled well regular classroom instructional activities in the way students able to internalize the subject matter including associated core competence domain skills and behaviors. In addition, academics support their classroom instruction with adequate laboratory demonstrations and fieldwork internships which were vital programmed activities for students to acquire more practical competence than theoretical dominated competence development.

Ahmed also affirmed that there were adequate and relatively faire resource provisions for academic purpose in the college although some procedural, interactional and benefit related injustices appeared occasionally in the deans leadership behaviors in the college. For instance, many academics feel discomfort during internship program placements and placement cites determination.

Likewise, Aemro M. from CMHS stated the quality statuses of his respective college graduates’ core competence domain development saying as follow: “Our College deserved very good to excellent performance of graduates’ competence development. They well-practiced field work.” In the same way, Azmeraw L. explained his respective college graduates’ competence development quality statuses in his own words and expression including the reasons for the identified statuses as:

Our college graduates acquired adequate knowledge, skill and values that fit program standards and community expectations. They demonstrate such competences in their field work practices and publication of research articles in reputable journals especially for post graduate programs. Our graduates showed better competence relatively to other universities as employers and alumni witnessed via the colleges’ tracer study documents. Their achievement test results for the majority are large scores which imply more internalization and competence, and they contributed valuable thesis research findings which cause improvement of crop and animal production in the last 5 years. Hence, the status of our graduates can be categorized as very good status in general. Exit exams were not administered regularly in each year due to lack of such system in the college (18 April 2022).

From Azmeraw’s expression of competence status and the factors for the identified statuses, the researchers understand that the college prepared its graduates with desired theoretical and practical competence. The post graduate program graduates have developed the skills to conduct research and suggest practical solutions for community problems of both crop production and animal rearing practices in the study time or abroad. Many post graduates also able to publish their research projects with in indexed journals in WoS or Scopus databases. Moreover instructions were supported by field work projects and internship programs which provided adequate practical competence for graduates that made ease employment opportunities as well as workplace performances.

A participant in CMHS at BDU also noted such reports about the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in the respective college.

Our graduates learn more and more practice based competence for each desired competence areas such as the field specific knowledge, skills and values for both undergraduate and post graduate programs especially the post graduate programs strictly follow every day learning activities in medical field works with their course instructors within hospitals. Every student assessments are done based on practical fieldwork operation applying their field specific or generic knowledge or skill with personal value developments. Therefore, no doubt that our college prepared graduates with best quality statuses. Even though, the college was accompanied with occasional intragroup conflicts among academics and the leaders could be for position or privilege competitions (20 Appril 2023)

From this interviewee’s evidence, we can understand that the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development could be generally best status and received best employment opportunity in the labor market.

In general the researchers can conclude that these colleges devoted ample rigors for the improvement of the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in the last 6 years.

For the same interview question, Habtu M in faculty of humanities (FH), reported that the status of graduates’ competence development a little bit different from Aemro M, Ahmed Y., Azmeraw L. and Mizanu B. judging generally good to satisfactory quality statuses in terms of professional expertise, desired skills and dispositional values. He justified the major reasons for the identified quality statuses as: the last 5 years’ time were dominated by war, leadership weaknesses at different levels in the college, insecurity and budget deficits. In support of these status judgments, Habtu in FH at BDU responded to the interview item: How do you judge your respective college quality statuses of graduates' core competence domain development in the last 5 years? Saying:

To me it is died. …Because I believe that the quality status of our graduates are below our expectations or standards such as: They lack future oriented thinking so that they showed limitation in terms of maintaining nature, shortage of preserving social values and wisdom for upcoming generation. Our college instructions did not significantly promote the connection between local and global events (values). Our instruction focus on lecturing and memorizing rather than searching and finding the new wisdom, Graduates lack critical and creative thinking to solve problems with in the institution and the community. Internship and practicum field works and their feedbacks were not genuinely well practiced, in the last 5 years (9 April 2022, 0:20).

Habtu M. further noted in the interview report as follow:

The poor quality of graduates may have some degree of association with the status of inputs used in graduates’ production process such as instructors’ and students’ identity(capacity, competence, interest…), instructional technology and infrastructure availability, Moreover, the production system or the process part such as instruction, curriculum, program management, internship fieldworks, practicum and other feedbacks have also considerable influence on the quality of the graduates in our college (9 April 2022, 0:20).

From Habtu’s finding, we can say that certain limitations (gaps) exist among the integrated functions of input resources, system perspectives and outcome standards (expectations) for determining graduates’ core competence domain development in the respective colleges. The participants expect the university graduates to have the core competences that enable them different from the non-graduate employees or other members in the population in terms of various competence domains or expertise areas or at least his or her expertise areas, various skills and various dispositional values acceptable by the community using the standards raised by Habtu M. or using other organized standard reference points.

Therefore, the colleges in their university need to use these findings to be aware of their graduates’ quality statuses of core competence domains development and accordingly apply the suggestions recommended to alleviate or at least reduce the problem so as to improve holistic sustainability alongside graduates’ quality, the labor force and nation developments.

To confirm these findings as valid, the researchers triangulated it with the previous study findings as discussed below

The contemporary educational paradigms revealed a shift from finally observable educational outcomes to initially observable practice based competences (Liu, Chu, Fang, Elyas, 2021). Competence-based training in universities and its evaluation system although get a scant attention recently, yet did not become adequately practical especially in universities from developing countries (An & Loe, 2022). There were many factors for this low practice of competence-based training and moderate graduates’ competence development in Ethiopian universities, specifically Bahir Dar University (BDU). A considerable university graduates in developing countries remained unemployed for long may be due to the fact that they lack the competences demanded by the labor market (employers) or lack the career opportunity for different reasons such as the labor market may be unable to absorb the available supply labor force or the labor market system problems (Semela, 2011). The quality statuses of graduates’ core competence domain development in many colleges at BDU were “good” to “very good” so that majority secured sustainable employment, (Kerebih et al., 2019).

4.2. University Exit-Exam Results as Indicator of Graduates’ Competence Development

RQ3.What does the university exit exam achievements infer about the quality of graduates’ competence development in the last 6 years (2017-2022) at BDU?

Scholars in the area have investigated the links between graduates’ achievement scores and the quality of competence the graduates actually displayed in the real work or life environment (Leithwood et al., 2004; Gomes et al., 2023). Scholars believed that graduates became more competent in their field specific competence areas (subject matter knowledge, skill and values) than generic/soft competence areas such as reasoning, problem solving, interpersonal relationship, conflict resolving… skills or competences,( McKay, 2005; Woods & King, 2002). Although, nationally prepared and administered university exit exam results unable to indicate distinguished and specific competence domains, it generally revealed quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in their stay at the university. For instance, the four colleges’ university national exit exam results were presented in Table 1, exhibit 1 for further interpretation in relation to quality statuses of graduates’ competence development.

Interpretation

The university exit exam result is a vital indicator for the graduates’ mastery of the core competencies domain as articulated in the specified curriculum and ensures the degree of readiness that the graduates satisfy the labor market requirements for employability and the quality of the labor force (Lo presti et al., 2022; De Vos & De Hauw, 10). The national exit exam of universities is a type of standardized assessment tool for measuring the graduates’ core competence domain development after its validity and quality have been tested and approved by professionals in the area (Belay, 2022). It is used for university students leaving and transitioning to the labor market.

As indicated in Table 1, Exhibit 1, 88.44% of the graduates of the three colleges and two faculties in BDU scored a pass mark of 50 or above on the national exit exam that was prepared and administered by MOE. It implies that the majority of the graduates are able to score above the minimum threshold of 50% as a requirement to pass and engage in the labor market and labor force in the country or abroad. This percentage can entail a general highlight about the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in the core competence domains that satisfy the minimum threshold, while for few students’ (11.56%), status was unsatisfactory.

Furthermore, the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development can be explained by applying more advanced statistics using the mean value and percent of graduates in each status rank, such as "satisfactory," "good," “very good” and “excellent” values. For instance, 93 (80.17%) graduates of the school of medicine scored marks within the range of 70–84 and 85 and above, which implies the majority of graduates achieved “very good” and “excellent” quality statuses in terms of their’ core competence domain development. The mean of graduates’ exit exam achievement value of 75.22 also indicated that the mean value fell in the middle of “very good” scale values, which implies that many graduates, even those who scored below the mean, are involved in the “very good” quality status of graduates’ competence development. Only 23 (19.83%) graduates scored exit exam results within a 50–69 scale interval, which implies these graduates achieved “good” quality status. There was no a graduate who scored below the “good” quality status, which implies that, the college generally prepared graduates who deserved desired quality standards and expectations satisfying the labor market requirements. Hence, the college had contributed a quality workforce who contributed a lot to the nation-wide developments in line with their occupations (Tekeste, 1990; Yorke, 2006; Gomes et al., 2023).

Likewise, the college of science at BDU trained 170 graduates, of whom 94.7% passed the exit exam prepared and administered by MoE, scoring 50 and above scores, which served as a cut-off point for passing and failing the labor market system for employment. The mean score value of 69.012 falls within the upper limit of the top value of the analysis scale, "50-69,” implying the quality status of the mean value, and those who scored above the mean of 93 (54.7%) are “very good” and "excellent," who deserve adequate graduates’ competence development that enables the graduates to receive better employment opportunities as well as such labor forces able to contribute substantial nation-wide developments in their occupational areas (Rychen & Salganik, 2003). In CS, 68 (40%) graduates also fell in the analysis scale interval of "50-69,” implying “good” quality status of graduates’ competence development, which inferred such graduates are also involved in the labor market system and may get the opportunity to be part of the labor force and contribute a lot to the nation's development. CS involved only 9 (5.2%) graduates who scored below the 50% cut-off point, which implies their competence development quality status was unsatisfactory or poor, inferring that such graduates did not deserve employment and unable to be part of the labor force in the country or abroad, as well as did not accomplish tasks well and contributed lower performance in their organization.

In addition, in the faculty of humanities, the university exit exam results indicated that 70% of graduates passed to the labor market system, acquiring at least the minimum threshold of a 50% university exit exam score and above, while a considerable number of graduates 49 (29.2%) failed due to obtaining a raw score below 50, which indicated these graduates achieved lower quality statuses in terms of their’ competence development, such as unsatisfactory and poor—and that the labor market system or employers were less likely to permit them employment opportunities. However, FH at BDU produced well-trained graduates (66, or 39.27%) who scored within the analysis scale interval of 70 and above, implying higher quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in the respective college. The remaining 53 (31.6%) graduates received a raw score within the analysis scale interval of 50–69, which implies a “good” quality status of the graduates’ competence development, which entailed the labor market that they acquired moderate competence in various competence domains, which enabled them to carry out tasks and perform well in the workplace.

4.3. Quality Statuses of Graduates’ Core Competence Domains

As indicated in Table 3, the majority of stakeholders (academics, graduates, and employers) in the interview data affirmed that the graduates deserved “very good” quality status in terms of communication skills, working with others, and subject-specific knowledge and skill core competence domains, while the tracer study findings from the questionnaire ratings of both graduates themselves and employers satisfaction judged these competence domains at “good” quality status. All the participant stakeholders also identified the remaining six core competence domains with a “good” competence status. Last, value-semantic and leadership core competencies were categorized into “Satisfactory to Good” status by the majority of the stakeholders and data sources, as demonstrated in Table 3.

From these evidences, we can suggest that the quality statuses of core competencies development of the graduates after completing a programme of study for 3 to 7 years stay in university belong to "good to very good” statuses, which imply that although the graduates acquired considerable magnitude of competence in each core competence domain that enabled them for employability, there would be substantial strategic improvements of the curriculum, the core competence learning activities and measurement standards., This model outcomes enable nation or citizens achieve holistic sustainable development(Gomes et al., 2023).

Table 3.

Summary of graduates’ core competence development statuses from major stake-holders’ and tracer study document perspectives.

Table 3.

Summary of graduates’ core competence development statuses from major stake-holders’ and tracer study document perspectives.

| Core competencies from the adapted model | Academics’ interview | Graduates’ interview | Employers’ interview | Kerebih et al, 2020 Tr. Study | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graduates rating | Employer view | Emp. sati sfaction | ||||

| Communication skill | Very good | Very good | Very good | 67 | 82 | 62 |

| Numeracy skill | Good | Good | Good | - | 80 | 59 |

| IT skill | Good | Good | Good | - | 76 | 58 |

| Learning how to learn | Good | Good | Good | - | 79 | - |

| Problem solving skills | Good | Good | Good | 68 | 81 | 59 |

| Working with others | Very good | Good | Very good | 76 | 85 | 63 |

| Subject specific knowledge and skill | Very good | Very good | Very good | 78 | 84 | 63 |

| Research and innovation skill | Satisfactory | satisfactory | Good | 69, 64 | 79 | 60 |

| Report writing and presentation skill | Good | Good | Good | 74 | 80 | 60 |

| Value-semantic and personality improving skill |

Satisfactory | Good | Good | 71 | 83 | 63 |

| Leadership competence | Satisfactory | Good | Good | 69 | 79 | 59 |

| Grand | Good-+ | Good+ | Good+ | 72 | 80 | 60 |

Note: Emp= Employers’, Tr= Tracer study. Tracer study findings were results of questionnaire scale items.

4.4. Major Causes for the Identified Statuses of Graduates’ Core Competence Domains

RQ3. What was/were the major causes for the identified quality statuses of graduates’ competence development may be in favor or against the normative public/personal point of reference?

The participants stated the major causes for the increasing or declining quality statuses of graduates’ core competence development in their respective colleges. For instance, the researchers identified the following from the interview transcript protocol document.

4.4.1. Practice versus Theory Based Training

Graduates’ pre-job fieldwork-based training or adequate internship experiences are linked with more practice-oriented graduates’ core competence development than theoretically focused competence (Zopiatis, 2007). It leads to better soft or generic skills (communication, report writing, emotional intelligence, analysis, reasoning, etc.) (McKay, 2005; Woods & King, 2002) and expertise skills (technical and field-specific subject-matter knowledge) (Harvey et al., 1997; Laker & Powell, 2011; Rosenberg, Heimler, & Morote, 2012), which determine the graduates’ career employability. Therefore, scholars claimed that students’ participation in internship programs or pre-job fieldwork-based training provides them with the opportunity to test their core competencies, dispositions, and attitudes towards specific career tasks or job pathways (Miller, 1990). Similarly, it permits the graduates to solve the gap between theoretical and practical competency development (Zopiatis, 2007).

4.4.2. Leadership quality

the respective college deans’ leadership behaviors and styles influence the synergy of academics, the graduates, the leaders', and the college’s resources in the process of accomplishing tasks and achieving overall goals (quality graduates, research productivity, etc.) that leads the college towards success, MDG4 and MDG8 (Abelha et al., 2020; UrRahman, Bhatti & Chaudhry, 2019; Ekmekcioglu, Aydintan & Celebi, 2018). Such influences can be both positive and negative, depending on the deans’ strong and weak leadership behaviors, the practice of leadership contingent contexts, and the leadership styles followed (UrRahman et al., 2019). The interviewees’ responses from CMHS, CS, and CAES indicated that their college deans often practice strong leadership behaviors of transformational and reward- or punishment-based styles accompanied by fairness and shared responsibilities, which are vital for the best quality statuses of graduates’ core competence development (Tang &Yeh, 2015). On the other hand, interviewees in the FSS and FH reported that their college deans’ frequently practiced weak leadership behaviors such as transactional or non-leadership styles, accompanied by relative injustice and unshared mission-vision-strategy core values of the colleges, which are determinants of the negative impact and low-quality graduates’ competence development (Zangoueinezhad & Moshabaki, 2011). Indeed, these college deans occasionally practice desired leadership behaviors with fairness and shared values that positively influence the respective colleges’ quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in the last 6 years from 2017 to 2022.

4.4.3. External Environmental Influence

The political context of the country, that is, the regional ethnic (race)-based group conflicts or wars between ethnic groups in the Ethiopian nation, influenced the education system at all levels by creating security problems in schools and HEIs. The wars between Tigray and Amhara ethnic groups, supported by the federal military force, continued for a year in 2020–21 and seriously affected the Amhara regional state educational institutions, even causing all schools in the region to close. In addition, the war between the Amhara ethnic group nation force and the Ethiopian federal military force, which began after the previous war in 2022/2023, also adversely affected the education system of ARS specifically and the country’s HEI system in general. Therefore, security problems, budget deficiency, and several psychological and social problems resulted from these wars, which were also negatively affecting the overall education performance in terms of the quality of graduates’ competence development and the academics’ research productivity in general (Kumilachew, Gubaye, Mohamed, & Abebe, 2021; Ibreck & Alex, 2022).

Even though, the sample university and the colleges in it are still able to achieve the desired quality status of graduates’ competence development by controlling and handling the stated environmental threats.

4.4.4. Employers’ Recruitment Problems

Students of higher education institutions became motivated to learn if the labor market systems had adequate capacity to absorb university graduates at the time. In addition, the labor market of the country needs to provide equal opportunity for various university and other education-level graduates regardless of ethnicity, gender, SES, religious affairs, age, color, and so on. However, interviewees reported that biased employment was common in our nation; even graduates were asked to pay beyond their family capacity to get employment with some employers, such as banking, education officials, etc. Moreover, some employers and institutions recruit graduates out of their specialization although the relevant specialization graduates are available in the labor market, which causes lowered workplace performance due to a horizontal skill mismatch (McGuinness, Pouliakas, & Redmond, 2017). In line with this, Kerebih et al. (2020) reported that 74% of the graduates were employed in jobs or positions related to their field of study and specialization, and 72.7% were employed in various government offices, while 21.8% were in private institutions, in addition to 5.4% being self-employed. This evidence implies that 26% of graduates were employed in jobs and positions unrelated to their area of specialization and field of study.

4.4.5. Instructional Variable Problems: (the graduates themselves, academics’ competence, program and curriculum relevance, resource and budget deficiency)

The students’ (graduates’) variables (goal-setting, effort, motivation, intelligence, readiness, etc.) during class room instruction in particular and their university life in general are important determinants for the achievement of desired quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in the respective college. In this regard, an interviewee (Eyasu, M.) in CMHS reported that “I have a dream to be a well-known medical doctor, a reputed, acknowledged, and respected physician in my country or abroad." This evidence implies that medicine students’ level of goal setting for their education is high and that they exert adequate effort and motivation for acquiring new knowledge and skills in their field-specific or generic competence development in their university education life. Likewise, a graduating class student in CS (Birhanu, B.) reported saying, “I have a plan to be a good scientist; I need to be a researcher in science... and contribute an innovation useful for the community." From what this student is saying about university education and science learning, researchers can understand that this student has a vision to achieve higher learning goals and is motivated now and then in his university life.

Another student from FSS opined about his university education and aspirations: “I am in doubt that I can succeed in my education. Many clever students who graduated from university in my residence were unemployed; therefore, I am afraid that I may also encounter such problems. Anyway, I need to complete my university education on time since time value is important for life." From this student's evidence, we can understand that his vision, mission, and goal setting were not clearly internalized and that his motivation, effort, and self-efficacy levels became moderate to low, which caused relatively lower performance and caused him to be less successful in academic life.

In line with these interviewees, scholars generally support their findings that students’ prior knowledge, motivation, goal-setting, effort, and readiness are very important determinants for their academic achievement and the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in core competence domains (Zhao et al., 2021; Brauer, 2021).

Academics’ competence in teaching graduates in BDU was adequate to enable the graduates to achieve the best quality statuses of competence development, as graduates and academic staff interviewees affirmed. Academics in the school of medicine deserved special thanks for their genuine competence-based instruction with an equal focus on practice and theory, especially for postgraduate programs. Next, academics who taught in CS, CAES, FSS, and FH played a larger role in producing quality graduates who acquired desired competence statuses in their respective colleges, although quality status differences were observed among colleges in favour of CMHS, CS, and CAES (Kerebih et al., 2020; Abelha et al., 2020; Kragt & Day, 2020).

The Program, the curriculum, the student needs, and the labor-market demand match or mismatch affect the quality status of graduates’ competence development in the respective colleges in the last 6 years (Kerebih et al., 2020; Brauer, 2021). The specialization areas and the curriculum designed to achieve desired specialization knowledge, skills, and values get more and more fitness if contemporary-oriented global and local contents are involved, theory and practice get balance, and adequate learner-educator interaction is designed in the curriculum. Furthermore, the curriculum and the specialization shall be designed considering the student needs and the labour market demands so that employment and competence fitness increase, then employer satisfaction increases, and ultimately nation-wide and worldwide developments such as SDG4, SDG8, etc. can be achieved (Abelha et al., 2020; McGuinnes et al., 2017).

5. Conclusions and recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

The quality statuses of graduates’ sustainable core competence development in various competence domains and the causes behind the identified statuses were investigated using data from the major stakeholders (academics, the graduates, and employers) perspectives, exit exam result and tracer study finding exhibits altogether in the respective colleges at BDU and the findings demonstrated that in CMHS, the quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in most core competence domains were judged as “very good and excellent” by all participated stakeholders for the last 6 years. The major reasons for this status were: better students’ commitment and effort to achieve planned goal; higher academics’ professional responsibility and competence; higher instructional delivery of balanced theory and practice; relatively better task oriented leadership behaviors practiced with fairness and shared vision-mission-strategy identities. The quality statuses of graduates’ competence development in CAES and CS were also judged as “Good+” while FSS and FH were judged as “Good -+” by all participated stakeholders. The major reasons for the quality statuses of CAES and CS were relatively closer to the stated causes for CMHS except magnitude vary to some extent in favor of CMHS. However the major reasons vary for FSS and FH that the magnitude of the previous causes substantially declined and additionally, these faculties received relatively less budget grant than the three colleges in BDU or abroad. The graduates’ sustainable core competence domain development leads to sustainable employability and sustainable labor force and sustainable holistic developments.

5.2. Recommendations

- The quality statuses of graduates’ competence developments in various competence domains across colleges shall be investigated regularly in the college or institutional level so that interventions shall be given accordingly.

- The top level leaders shall give the desired attention to the faculties relative to the three colleges in terms of budget and other supports needed.

- Whatever leadership theory or style the deans (leaders) followed, leaders’ leadership behavior practice and the control of the leadership contingent contexts (justice, culture, …) shall develop relatively shared identity to adequately direct the staff and students effort toward achieving desired common goal (quality of graduates’ core competences development).

- College instructions shall be improved towards equal attention to both theory and practice and also focus on core competences domains more demanded by employers such as teamwork skills, innovative ability, research skills, problem solving skill, critical thinking, field specific subject matter knowledge, generic skills … School of medicine can be taken as best practices that shall be shared for other colleges

- The external environment influence especially the political context influence in terms of ethnic group conflicts and wars created security problems for universities even some universities were closed their regular teaching learning process. Therefore, the government shall alleviate ethnic concerns and build peace and security for affected universities.

- Employers both government and private shall recruit candidates based on genuine and fair selection criteria free from biasedness, and merit based employment shall be reinforced.

Author Contributions

The first author conceived the research idea, developed the background, the problem, the methods, analysis and discussion with conclusion and recommendation. He wrote the research project report. The second and third authors conducted editing and advising services at each stage.

Funding

The authors did not receive funds from any funding organization.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate and provide thanks for the sample universities and the participants for their cooperation and support at the time of collecting data and throughout the entire investigation processes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared that there is no known conflict of interest referring this study.

Ethical Clearance Approval

Bahirdar University College of Education and Behavioral Sciences Research Ethics Approval Committee (BDUCEBSREAC) had approved this study using protocol reference No. CEBS-0054/04/03/2022 and CEBSV/D1.3/06/022/22 on March 05/2022. The researchers also received the participants’ consent through asking them voluntarily cooperate.

References

- Abelha, M.; Fernandes, S.; Mesquita DSeabra, F.; Ferreira-Oliveira, A.T. Graduate employability and competence development in higher education—A systematic literature review using PRISMA. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- An, B.P.; Loes, C.N. Participation in High-Impact Practices: Considering the Role of Institutional Context and a Person-Centered Approach. Res High Educ. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Billet, S. Integrating Practice-Based Experiences into Higher Education; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, S. Towards competence-oriented higher education: a systematic literature review of the different perspectives on successful exit profiles; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cer, E. The instruction of writing strategies: The effect of the metacognitive strategy on the writing skills of pupils in secondary education; SAGE Open, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciraso-Calí, A.; Martínez-Fernández, J.R.; París-Mañas, G.; Sánchez-Martí, A.; García-Ravidá, L.B. The Research competence: acquisition and development among undergraduates in Education Sciences. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 836165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Begum, J.; Saiyad, S. Validated checklist for assessing communication skills in undergraduate medical students: bridging the gap for effective doctor-patient intera-ctions. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2023, 47, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CRSC [Core Renewal Steering Committee]. Learning Outcomes for the University Core Curriculum: Final Report; Loyola University: Chicago, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Croswell, J. W. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 4th ed.; Sage publications Inc.:: Los Angeles, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter, M; Jele, A.; Major, Z.B. The model of maximum productivity for research universities SciVal author ranks, productivity, university rankings, and their implications. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 4335–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; De Hauw, S. Linking competency development to career success: exploring the mediating role of employability, Vlerick Leuven Gent Working Paper Series, 2010. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.

- Divine, R.; Linrud, J.; Miller RWilson, J.H. Required internship programs in, marketing: Benefits, challenges and determinants of fit. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2007, 17, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, E.; Bennett, N.; Carre, C. Skill Development in Higher Education and Employment. In Differing Visions of Learning Society; Coffield, F., Ed.; Bristol: Policy Press: 2000.

- Ekmekcioglu, W.E.B.; Aydintan, B.; Celebi, M. The effect of charismatic leadership on coordinated teamwork: A Study in Turkey. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 1051–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epanchintseva, G.; Bukhtiyarova, I.; Panich, N. Comparative Analysis of Perfectionism and Value-Semantic Barriers of the Student's Personality. TEM Journal 2021, 10, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Alves, R.A. Research and teaching writing. Reading and Writing 2021, 34, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.; de Jesus Gomes, M.; da Cunha Moniz, A.; Américo, J.; Afonso, A.; Marçal, J. A Study of the Attribute of Graduates and Employer Satisfaction—A Structured Elements Approach to Competence and Loyalty. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies 2023, 11, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]