Submitted:

30 December 2023

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Device Fabrication

2.3. Device Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

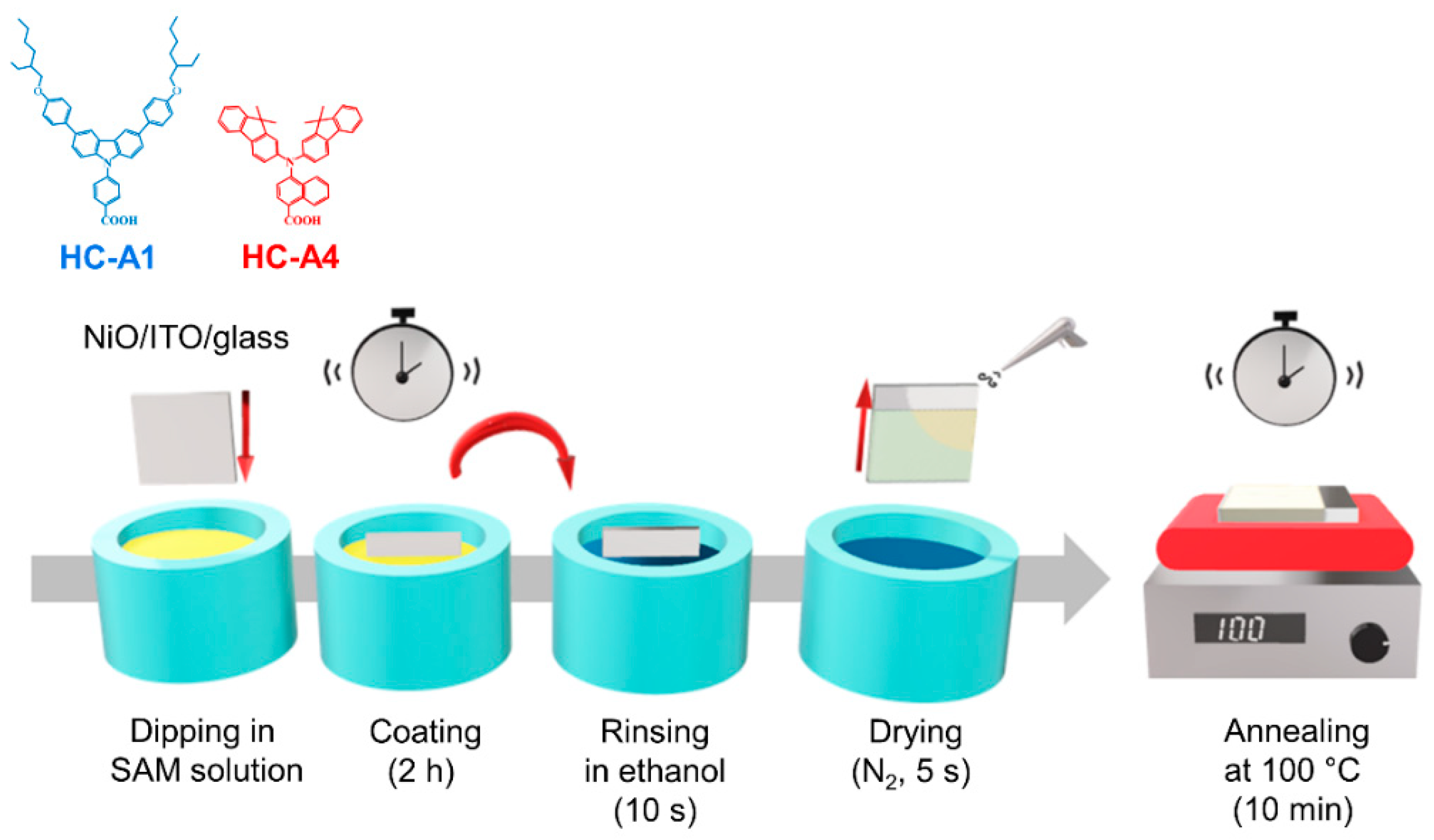

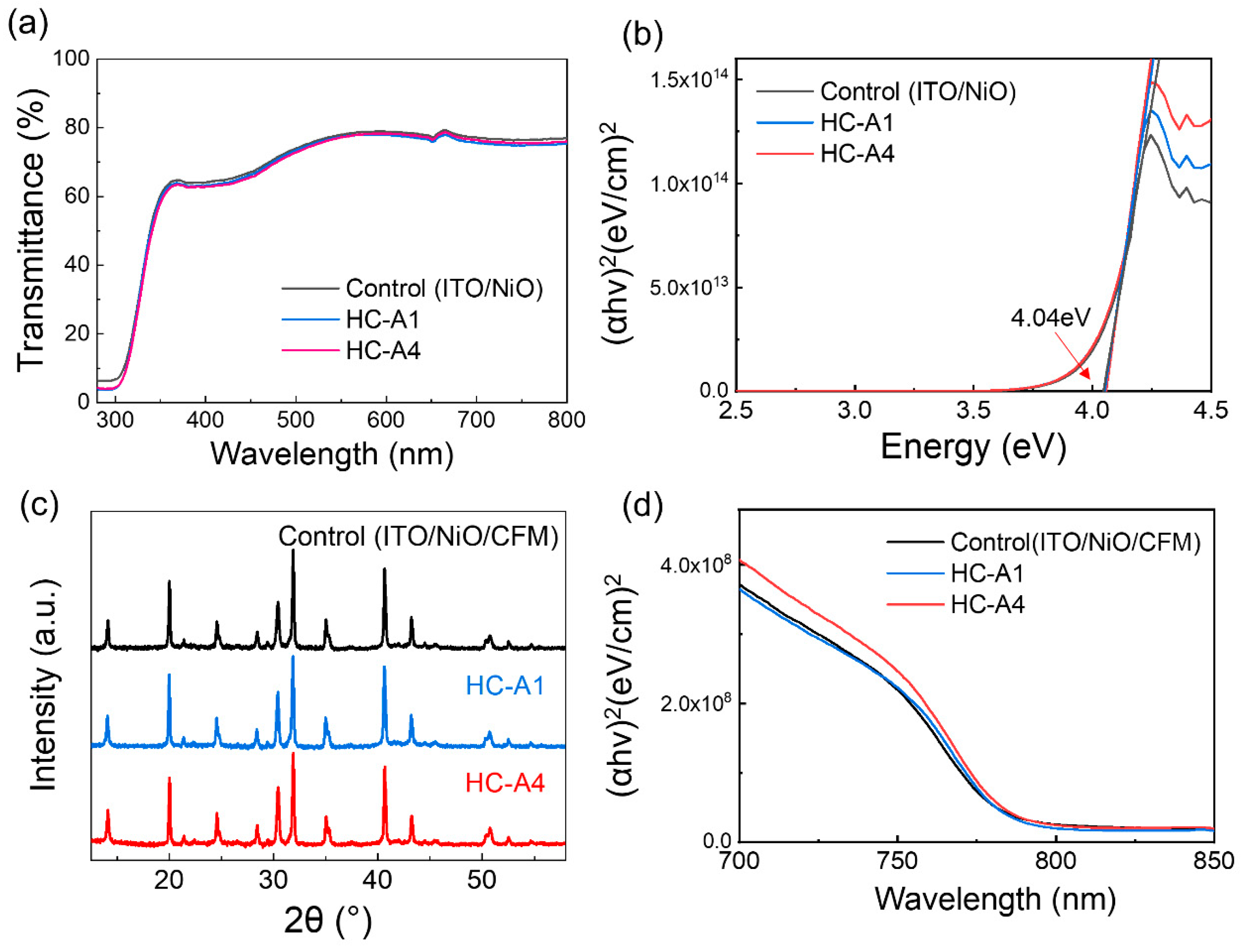

3.1. Fabrication and Characterization of SAM

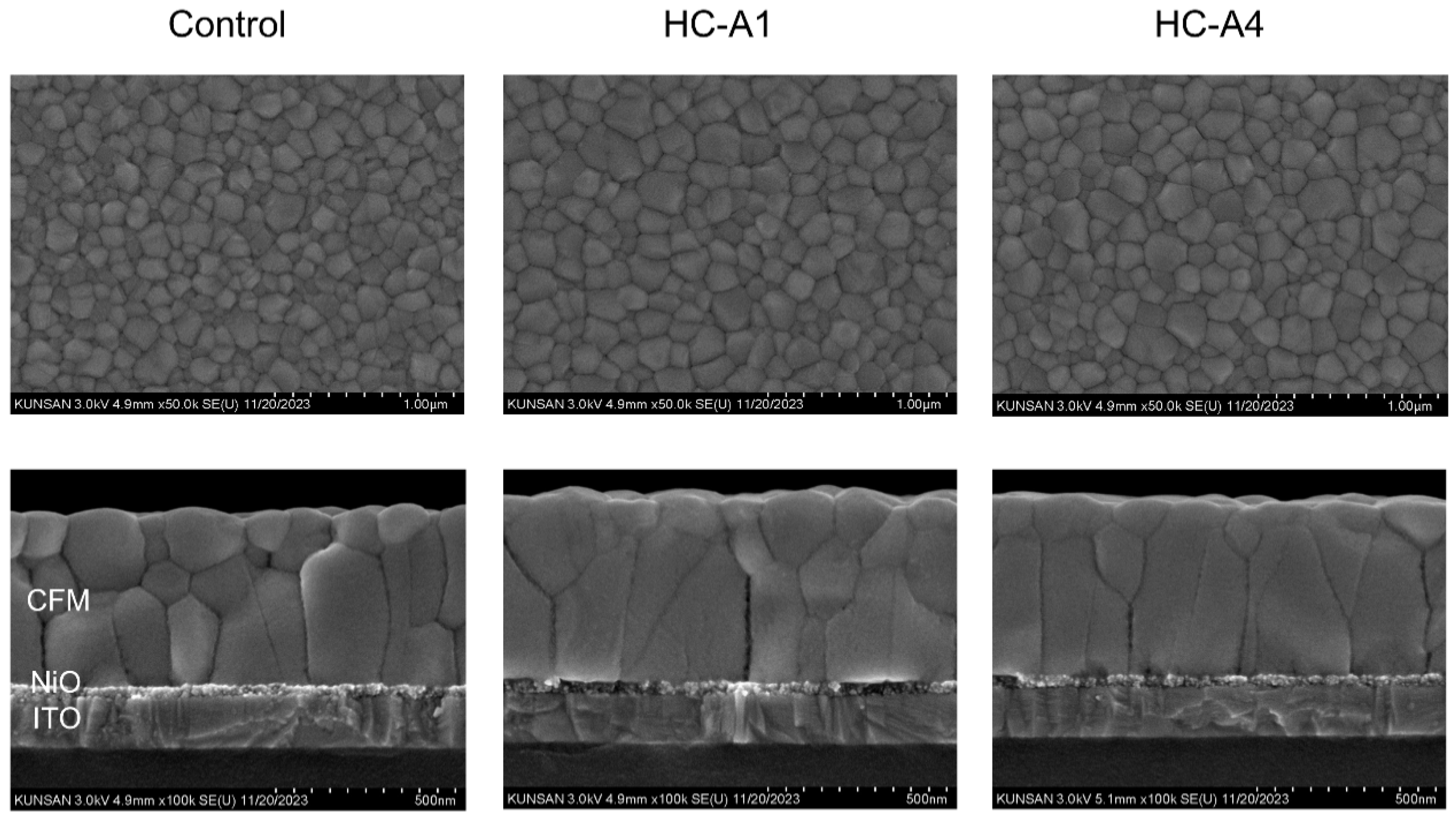

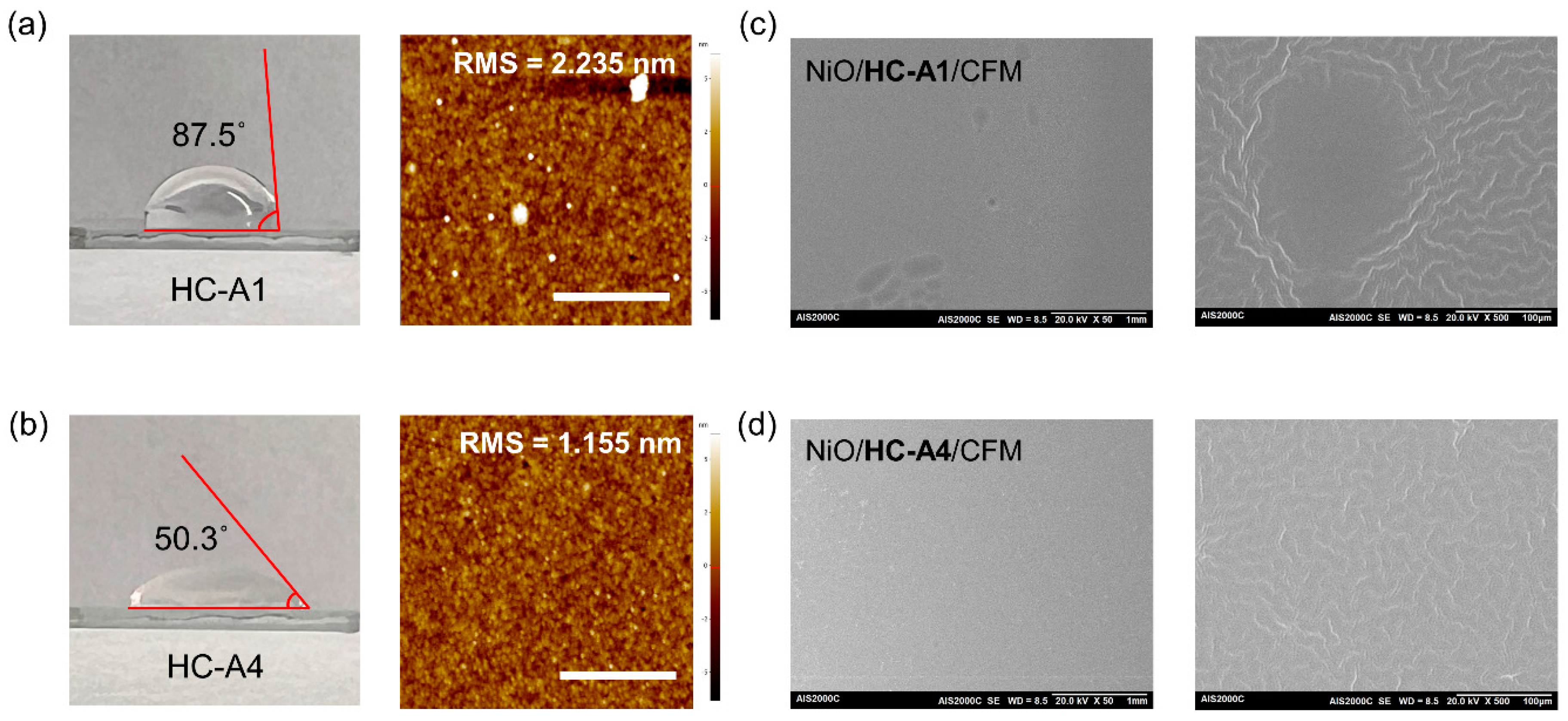

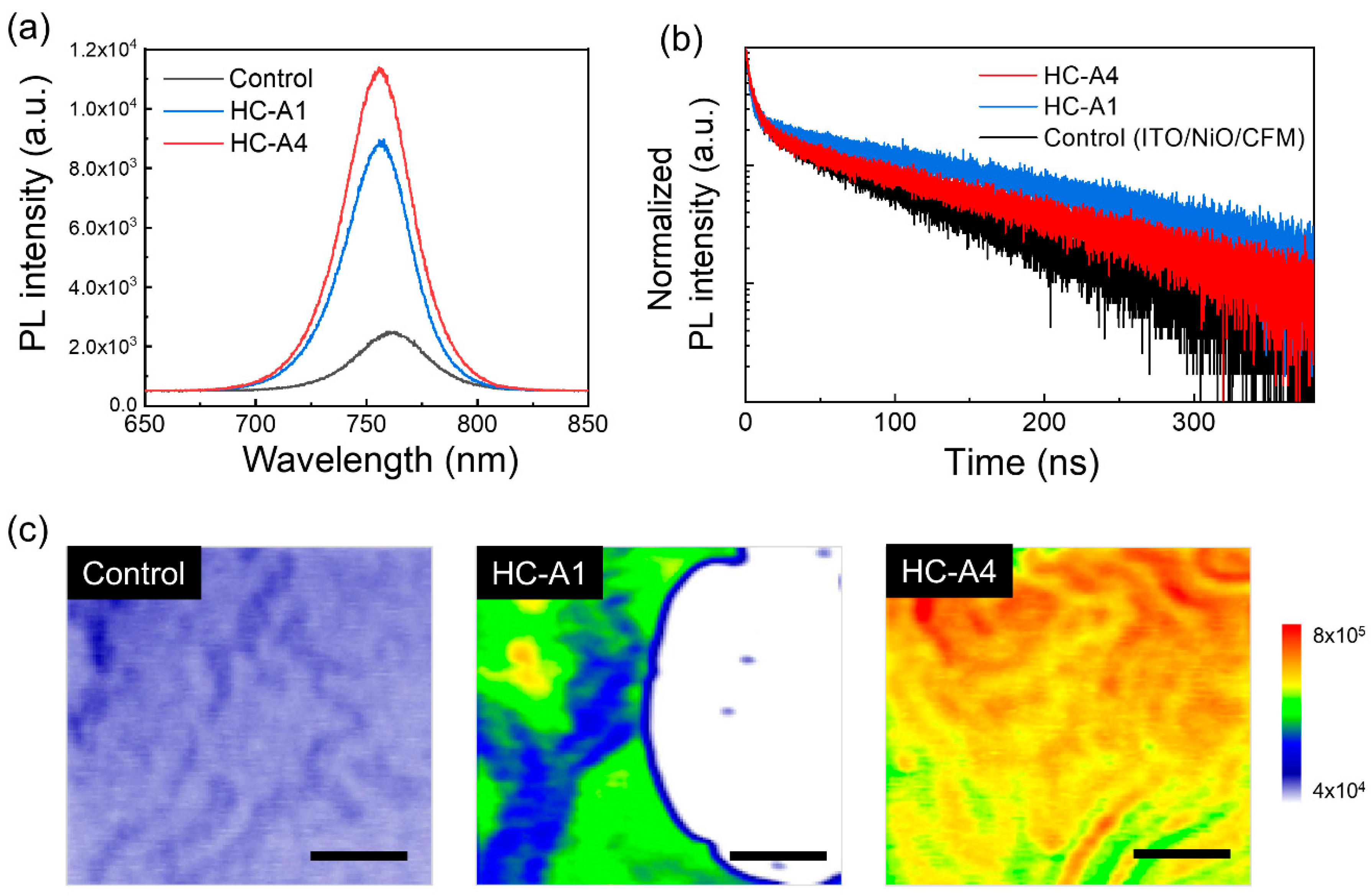

3.2. Surface Modification via SAM Molecules

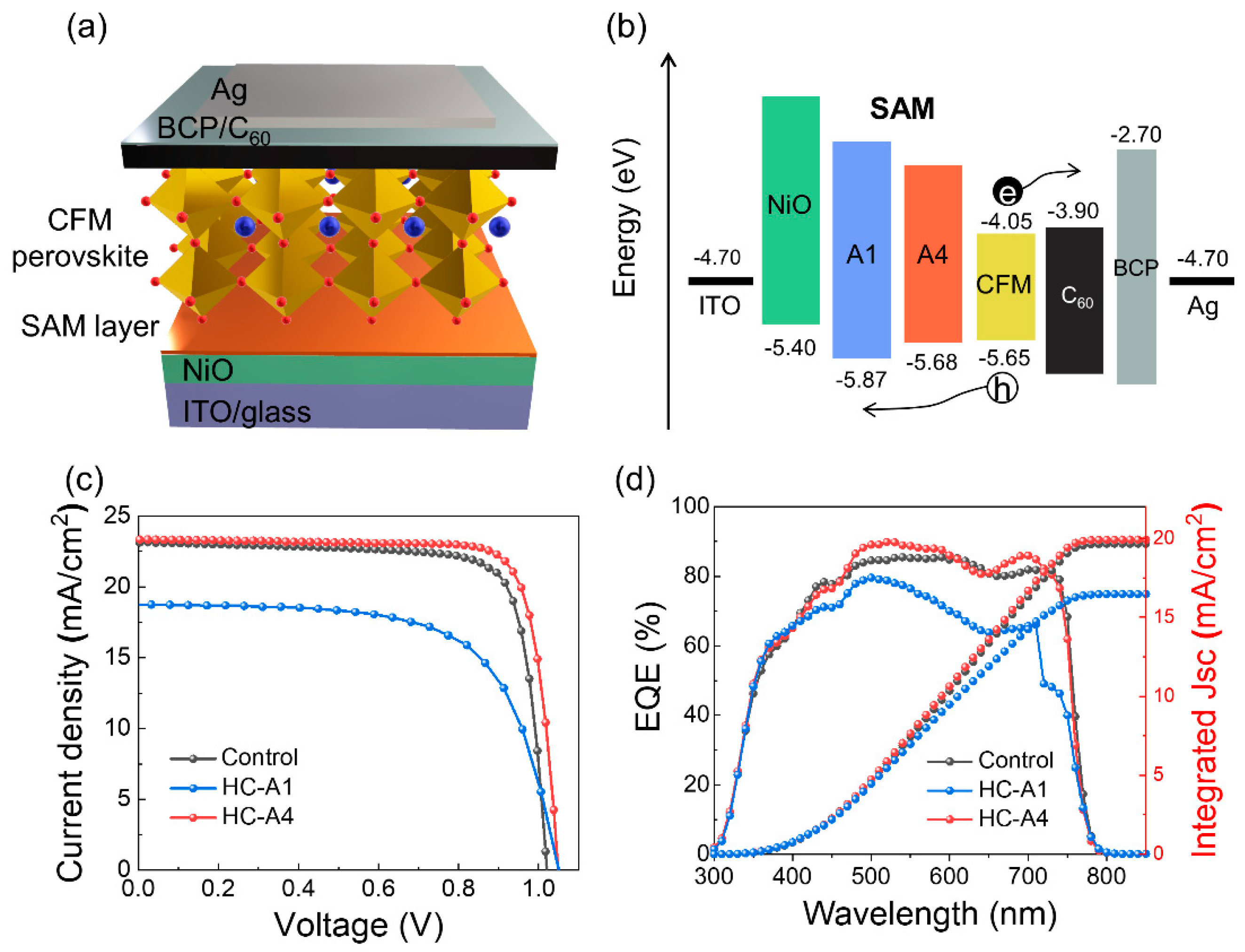

3.3. Carrier Extraction via SAM Molecules

3.4. Device Characterization with SAM Molecules

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kojima, A.; Teshima, K.; Shirai, Y.; Miyasaka, T. Organometal Halide Perovskites as Visible-Light Sensitizers for Photovoltaic Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6050–6051. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J., et al., Pseudo-halide anion engineering for α-FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells. Nature, 2021. 592(7854): p. 381-385.

- Meng, L.; You, J.; Guo, T.-F.; Yang, Y. Recent Advances in the Inverted Planar Structure of Perovskite Solar Cells. Accounts Chem. Res. 2015, 49, 155–165. [CrossRef]

- Aina, S.; Villacampa, B.; Bernechea, M. Earth-abundant non-toxic perovskite nanocrystals for solution processed solar cells. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4140–4151. [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, M.; Vesce, L.; Di Carlo, A. Upscaling of Carbon-Based Perovskite Solar Module. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 313. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-H.; Yum, J.-H.; Moon, S.-J.; Chen, P. Inorganic p-Type Semiconductors: Their Applications and Progress in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells and Perovskite Solar Cells. Energies 2016, 9, 331. [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Nishitani, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; Kusumoto, S.; Uchida, R.; Matsui, T.; Kawano, K.; Sekiguchi, T.; Kaneko, Y. Improving the Open-Circuit Voltage of Sn-Based Perovskite Solar Cells by Band Alignment at the Electron Transport Layer/Perovskite Layer Interface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 27131–27139. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.C.; Kim, M.; Lee, M.; Yang, J. Phenoxazine-benzimidazolium ionic hole transport material for perovskite solar cells. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2023, 44, 827–830. [CrossRef]

- Schloemer, T.H.; Christians, J.A.; Luther, J.M.; Sellinger, A. Doping strategies for small molecule organic hole-transport materials: impacts on perovskite solar cell performance and stability. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 1904–1935. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Chen, L.; Guo, Z.; Ma, T. Strategic improvement of the long-term stability of perovskite materials and perovskite solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 27026–27050. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y., et al., Silver Iodide Formation in Methyl Ammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite Solar Cells with Silver Top Electrodes. Advanced Materials Interfaces, 2015. 2(13): p. 1500195. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C., et al., Oxidized Nickel to Prepare an Inorganic Hole Transport Layer for High-Efficiency and Stability of CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells. Energies, 2022. 15(3): p. 919. [CrossRef]

- Aboulsaad, M.; El Tahan, A.; Soliman, M.; El-Sheikh, S.; Ebrahim, S. Thermal oxidation of sputtered nickel nano-film as hole transport layer for high performance perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 19792–19803. [CrossRef]

- Di Girolamo, D., et al., Progress, highlights and perspectives on NiO in perovskite photovoltaics. Chemical Science, 2020. 11(30): p. 7746-7759.

- Zhang, B.; Su, J.; Guo, X.; Zhou, L.; Lin, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhang, J.; Chang, J.; Hao, Y. NiO/Perovskite Heterojunction Contact Engineering for Highly Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1903044. [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; He, K.; Zhao, X.; Li, B. Defect Passivation Scheme toward High-Performance Halide Perovskite Solar Cells. Polymers 2023, 15, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Chu, Z.; Ye, Q.; Li, X.; Yin, Z.; You, J. Surface passivation of perovskite film for efficient solar cells. Nat. Photon- 2019, 13, 460–466. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, K. Additive Engineering for Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Liao, C.; Chueh, C.; Zuo, F.; Williams, S.T.; Xin, X.; Lin, J.; Jen, A.K. Additive Enhanced Crystallization of Solution-Processed Perovskite for Highly Efficient Planar-Heterojunction Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 3748–3754. [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, M.; Shi, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Liao, L. Controllable Perovskite Crystallization by Water Additive for High-Performance Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 6671–6678. [CrossRef]

- Guarnera, S., et al., Improving the Long-Term Stability of Perovskite Solar Cells with a Porous Al2O3 Buffer Layer. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 2015. 6(3): p. 432-437.

- Shibayama, N.; Kanda, H.; Kim, T.W.; Segawa, H.; Ito, S. Design of BCP buffer layer for inverted perovskite solar cells using ideal factor. APL Mater. 2019, 7, 031117. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Cho, S.J.; Byeon, S.E.; He, X.; Yoon, H.J. Self-Assembled Monolayers as Interface Engineering Nanomaterials in Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Roldán-Carmona, C.; Sohail, M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K. Applications of Self-Assembled Monolayers for Perovskite Solar Cells Interface Engineering to Address Efficiency and Stability. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yin, J.; Yuan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, N. Thiols as interfacial modifiers to enhance the performance and stability of perovskite solar cells. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 9443–9447. [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Yuan, R.; Pfalzgraff, W.C.; Nishida, J.; Wang, L.; Markland, T.E.; Fayer, M.D. Unraveling the dynamics and structure of functionalized self-assembled monolayers on gold using 2D IR spectroscopy and MD simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 4929–4934. [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.T.; You, B.S.; Eom, Y.K.; Ju, M.J.; Choi, W.S.; Kang, S.H.; Kang, M.S.; Seo, K.D.; Hong, J.Y.; Song, S.H.; et al. Triarylamine-based dual-function coadsorbents with extended π-conjugation aryl linkers for organic dye-sensitized solar cells. Org. Electron. 2014, 15, 3316–3326. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S., et al., Novel D–π–A structured Zn(ii)–porphyrin dyes with bulky fluorenyl substituted electron donor moieties for dye-sensitized solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2013. 1(34): p. 9848-9852.

- Nasiri-Tabrizi, B. Thermal treatment effect on structural features of mechano-synthesized fluorapatite-titania nanocomposite: A comparative study. J. Adv. Ceram. 2014, 3, 31–42. [CrossRef]

| Sample | A1 (%) | τ1 (ns) | A2 (%) | τ2 (ns) | A3 (%) | τ3 (ns) | τavg (ns) |

| Control | 0.61 | 2.537 | 0.15 | 14.402 | 0.19 | 88.072 | 73.81 |

| HC-A1 | 0.77 | 2.236 | 0.10 | 13.647 | 0.23 | 213.303 | 201.11 |

| HC-A4 | 0.61 | 2.938 | 0.21 | 11.438 | 0.17 | 137.043 | 117.33 |

| VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | |

| Control | 1.02 | 23.13 | 79.81 | 18.81 |

| HC-A1 | 1.05 | 18.79 | 66.06 | 13.04 |

| HC-A4 | 1.05 | 23.34 | 81.80 | 20.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).