1. Introduction

Nepal’s forefathers created cultural heritage to preserve Nepal’s cultural identity and history. From the Lichchhavi era, a plethora of civic, social, religious, and cultural institutions, known as guthis, emerged in Nepal to manage and preserve the nation’s cultural heritage. These institutions were deeply rooted in ancient legal systems and cultural beliefs. However, during the Lichchhavi period, there were no specific guidelines for the systematic preservation of history (Amatya, 1988, 2007; Bajracharya, 1978; Greer, 1994; Tandon, 1995). The term "guthi" comes from the Sanskrit word "gosthi," which means "gathering" or "association," with a particular emphasis on religious and socio-cultural values (Dangol, 2010; Regmi, 1978; Toffin, 2005). A guthi is a collective formed by an individual or members of a family united by common caste, patrilineal lineage, or specific geographical characteristics (Corporation, 2015; Nepali, 1965).

According to Harvey (2015), The lack of consensus on the definition of cultural heritage persists, despite its significant presence in academic inquiry, research, and media discussions of preservation (de la Torre, 2013; Harvey, 2015; Shakya & Drechsler, 2019b). "Conservation" includes actions to preserve the cultural significance of a site (KC et al., 2018, 2019; Truscott & Young, 2000; Truscott, 2014). UNESCO distinguishes "heritage" from "cultural heritage," which refers to irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration, including monuments, architectural works, archaeological elements, inscriptions, and more (Besana, 2019; Conference & Educational, 2003; Council, 2012; Hassani, 2015).

In Europe, heritage sites were often managed by trusts, foundations, or government agencies that owned land or assets. However, available information doesn’t explicitly mention land donation systems dedicated to heritage conservation from the time monuments were established (Martínez, 2016). In addition, many countries use public-private partnerships to preserve their cultural heritage. In these collaborations, organizations offer financial support in exchange for exclusive rights or benefits (Throsby, 2016). There are various situations in Africa where the management and conservation of cultural heritage are linked to land or natural resources. For example, community-based conservation strategies may involve local people owning or managing property in a way that supports both the conservation of cultural sites and their livelihoods (DeGeorges & Reilly, 2009; Galvin et al., 2018; Jugmohan et al., 2016; Turner, 2013; Wasonga et al., 2010).

Guthi is a longstanding framework rooted in social cooperation that aims to impart moral teachings, promote religious values, preserve traditional methods, and foster discipline. It introduces an ancient approach that effectively preserves history through authentic designs, local resources, and a technology approach that is relevant even in the absence of modern engineering education or technology. Through cooperative land ownership, guthi contributed to the development of both social and material wealth. It supported the maintenance of culturally important structures and artifacts while involving the local community in rituals and festivals (Shaha, 1992; Tandon, 1995, 2020). The government’s implementation of land nationalization policies since 1960 poses a significant threat to the essential functions of traditional community guthis (Regmi, 1978; Toffin, 2005). This paper seeks to fill a current gap by highlighting the importance of ancient heritage conservation methods that show increased effectiveness through greater community involvement and the use of indigenous knowledge linked to financial aspects through land connections. This approach contrasts with the current trend in heritage conservation and management.

Guthi founders contributed property, often in the form of land, to ensure the enduring sustainability of the institution. For many generations, land was considered the most valuable and enduring asset, funding all of the organization’s activities. As custodians of our cultural heritage, the guthi system oversees over 12,000 significant religious structures, about half of which are under its jurisdiction, according to Guthi Corporation records. The Corporation manages and preserves approximately 2,300 government-registered monuments, while there are numerous other families, individual, and organizational guthi. Under the Guthi Corporation Act of 1976, government-managed guthis are categorized as Rajguthi and take three forms: Amanat guthi (directly managed by the Guthi Corporation), Chhut guthi (supervised by the head of the shrine, appointed by the Guthi Corporation), and Private guthi (not under the supervision of the Guthi Corporation). Rajguthi refers to designated land or its income that is specifically earmarked for the maintenance of temples, riverbanks (ghats), or both. These funds support charitable endeavors, including aid to Brahmins and the underprivileged, under the wishes of the benefactors (Corporation, 2015).

Nepal has an enduring cultural legacy left by its ancestors, but piecing together our rich heritage is challenging due to a lack of historical understanding. After the destruction of the Buddhist civilization at Kapilavastu in the late 6th century BC, a new civilization took root in Nepal. From literary and archaeological evidence, it’s clear that various groups who migrated from northern India in Buddha’s later days played a pivotal role in shaping Nepal’s distinct civilization (Amatya, 2007; Dulal & Bhattarai, 2023).

Between 1950 and 1951, social values, interests, and preferences changed. The advent of democracy had a profound effect on our way of life, allowing the nation to modernize. As a result, the inclination of individuals to allocate excess resources and savings to spiritual, cultural, and religious endeavors has diminished. This trend has led to the decline of traditional institutions such as the guthi. From 1950 to 1951, our social goals, attitudes, and tastes evolved. The advancement of democracy had a significant impact on our established way of life and facilitated the modernization of the country. Over time, people began to devote fewer resources and savings to religious, cultural, and pious activities. These changes contributed to the decline of long-standing institutions such as the guthi (Amatya, 1988, 1994, 1999, 2007, 2011a, 2011b; Corporation, 2015; S. R. Subedi, 2022).

This study examines the extensive history of the guthi and its role in preserving Nepal’s cultural heritage with an emphasis on sustainability. It aims to preserve Nepal’s cultural heritage, which includes historical sites, monuments, and traditions, by encouraging community participation, financial support, and the promotion of indigenous knowledge within the guthi system. The primary goal is to strengthen and empower the guthi system, which is essential for the preservation of Nepal’s cultural heritage. Using a qualitative approach, the methodology integrates case studies, observations, and discussions involving historians, elders, archaeologists, government agencies, and local communities, with a focus on analyzing these managed heritage conservation systems.

A significant amount of secondary data was collected from the Scopus database using keywords from journal titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles, as detailed in

Table 1. This resource serves as a comprehensive repository, collecting materials essential for in-depth research efforts, whether general or specialized (Togia & Malliari, 2017).

The guthi system plays a central role in the preservation and management of cultural heritage, and 107 relevant papers were identified for a systematic review.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Function of Guthi

The Guthi Corporation Act of 1976 defines a "guthi" as a socio-religious institution established by a philanthropist through the donation of movable or immovable property, income-producing assets, or funds. This dedication is for the support of shrines, festivals, temples, construction, maintenance of various facilities, or religious and philanthropic purposes (GoN, 1976).

According to Tiwari (2002, 2013), A body known as the guthi fulfills social and religious duties within the Newar society. The functions of the guthi are intertwined with the life cycle events of clan groups and various aspects of social, religious, and cultural life. It’s emphasized that the guthi plays a crucial role in ensuring financial stability within the community, as asserted by Tiwari. "The Lichchhavi inscriptions illustrate the well-established practice of managing, operating, and preserving religious, social, and cultural elements in urban areas. These inscriptions, found in places such as Patan within the valley, highlight the gosthi system - a corporate organization sustained by continuous land grants or fixed deposits. Both government agencies and private individuals established these entities to ensure the continued operation and maintenance of community-serving elements and activities. This was done to protect them from future financial challenges or decline. The permanence in both institutional and financial aspects ensured their continuity and evolved into the present-day "guthi system" (Tiwari, 2002, 2013).

According to Panta (2002) and Pant and Shrestha (2016), each inhabitant of the town joins community associations known as guthi, which is one of the Newar, community’s most significant characteristics. Guthi are organizations set up to keep an eye on communal, social, and religious events including musical performances, ancestral worship, burial ceremonies, and caring for and performing daily rituals for temples and their upkeep. Although the guthi community vc associated with temple rituals are socio-religious and festivals are territorial, ancestor worship and funeral rites are organized based on caste and part-lineal groupings (Pant & Shrestha, 2016; Pant & Pant, 2002).

Tandon (2020) defense since the beginning of recorded Nepalese history, Nepalese have been familiar with the Nepali model trust, a type of cooperative devoted to religious and secular communal activities for which property is allotted to create income. Inscriptions at Changunarayan from the time of King Manadeva in 578 first refer guthi. This system has been in continuous operation ever since, despite experiencing numerous ups and downs throughout time. Tandon continued by saying that guthi is the endowment of income-producing assets for perpetuity to fund certain religious, philanthropic, or benevolent endeavors (Tandon, 2020).

Guthis was originally established to promote public welfare through religious endeavors such as the erection of idols, the construction of temples, and the performance of rituals. Currently, guthi lands that have economic value are attracting interest from buyers or cultivators who wish to convert them into raikar property. There is ongoing uncertainty about the merits of selling or converting all guthi holdings in the Kathmandu Valley and Nepal into raikar lands. Rumors are circulating in the Valley that the government may soon end dual land ownership (Corporation, 2015, 2019, 2020, 2021; Shrestha, 2016a; S. R. Subedi, 2022; Tandon, 1995, 2020).

Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the historical development of the guthi system in Nepal, highlighting its important role in preserving cultural riches throughout the ages (Gellner, 1996; Gellner, 1994; Gellner & Letizia, 2019; Maharjan, 2021; M. B. F. T. Maharjan, 2018; Nepal & Marasini, 2018; Pradhananga et al., 2010; Sarveswar & Shakya, 2021; Scott, 2019; R. S. Subedi, 2022a; Toffin, 2005, 2021; Vajracharya, 1998).

2.2. Contribution of Cultural Heritage Via the Guthi System Across Various Eras

The guthi system contributes to the preservation of Nepal’s cultural heritage in the following ways (Amatya, 1988, 1999; Chapagain, 2008; M. Maharjan, 2018; M. B. F. T. Maharjan, 2018; Scott, 2019; S. R. Subedi, 2022):

Temple and Monument Preservation: Guthis often take on the responsibility of maintaining temples, monasteries, and historical landmarks, playing an important role in preserving their architectural and artistic heritage.

Cultural Celebrations: Guthis organizes and sponsors cultural festivals and events that are crucial to preserving ancient customs, rituals, and artistic expressions. These events serve as a bridge to pass on cultural traditions to future generations.

Education and cultural awareness: Many guthis are involved in educational initiatives, supporting schools and institutions that teach traditional arts, crafts, and religious practices. This promotes awareness of the importance of cultural heritage among younger generations.

Community Development: Guthi-managed funds often support community development projects that include infrastructure improvements, health care, and social welfare. This holistic approach indirectly supports heritage conservation by empowering the community.

Resource Sustainability: Certain guthis oversee land, forests, and natural resources, implementing sustainable practices to actively conserve the environment. These efforts are critical to protecting the surroundings of heritage sites.

Guardianship of Sacred Sites: Guthis often serve as guardians of revered sites and artifacts, tasked with protecting these areas, maintaining reverence, and preventing unauthorized activities or intrusions.

While historically beneficial for heritage conservation, the guthi system faces modern challenges. Current discussions revolve around its modernization and regulation to address transparency, accountability, and adaptation to changing social and economic contexts. Below are explanations of different Nepalese eras (Chapagain, 2008; Pradhananga et al., 2010; Silva, 2016; Siwakoti & Adhikari, 2018):

2.2.1. Lichchhavi Period

The Lichchhavi era (400-750) marked an era of exceptional tranquility, prosperity, and cultural progress. It was during this time that the guthi system, a distinctive approach to conservation, emerged. The earliest written records mentioning the guthi system date back to the Lichchhavi period. The Panchali, a council of monks and village priests, also existed during this period (Shrestha, 2016b). The inscription on the Chabahil chaitya, believed to date from the reign of the Lichchhavi king Manadeva I (5th century AD), records the donation of arable land. This land was not only for the daily worship at the Chaitya but also to support the Bhikshu Sangha, the group of monks who perform these rituals. Similarly, King Jayalambha allotted land to ensure the continued worship of the Jayaswor Shiva linga that he had dedicated. An inscription at Pashupati in 491 mentions the worship of the deity on certain days, using the Sanskrit term karana puja for occasional worship. The inscription emphasizes the importance of sustainability with the phrase "yanarthandattam ksheyaniyam". King Manadeva I’s inscription at Pashupati Chhatrachandeshwor mentions a donation of land for deity worship and emphasizes the donor’s explicit instructions to ensure its longevity and proper care. Remarkable for its warning against the selfish use of the guthi, this inscription underscores the responsibilities associated with its use (Bajracharya, 1996). A Bharavi inscription in Mangal Bazar records the construction of a water tap and the provision of land for ongoing funding to maintain it (Bajracharya & Malla, 1985; Bajracharya, 1996; Malla, 2005).

Shivadev Amshuvarma’s Lele inscription of 604 mentions the guthi and shows different types: Brahma gosthi (Brahmin association), Pradeepa gosthi (lighting lamps in temples), Paniya gosthi (providing water to remote areas), Malla Youddha gosthi (managing entertainment), Dhup gosthi (managing incense), Indra gosthi (overseeing the festival of God Indra), Baditra gosthi (managing music), Archa gosthi (carving images), and Archaniya gosthi (managing worship). These gosthi were initially divided into two types: the first managed by family members and the second by a collective of individuals from the same clan, similar to the later division into ghar guthi and institutional guthi (Amatya, 2007; Bajracharya, 1996).

Narendradev, a Lichchhavi monarch, noted in an inscription that the guthi of local users were responsible for the maintenance and cleaning of the temple, funded entirely by the proceeds of donated land. Brahmins and Pashupat were supported by the surplus funds. This arrangement fostered a sense of ownership and responsibility within the community for its heritage. The Acharyas of the Vamsha Pashupat sect were entrusted with the management, maintenance, and restoration of the Shrishivadeveshwor Mahadev temple, using the entire income from the donated land. Here are key facets of the guthi system that made it highly effective for conservation during the Lichchhavi era (Bajracharya, 1978, 1996):

Community ownership and responsibility: The guthi system is based on community ownership and accountability. This means that every member of the guthi has a stake in its prosperity and shares responsibility for maintaining the assets under the guthi’s care.

Financial Stability: Supported by membership fees, user fees, and investment income, the guthi system ensures a steady cash flow. This secure funding enables the guthi to reliably cover maintenance and repair costs.

Adaptability: The guthi system demonstrates flexibility by adapting to circumstances. For example, when guarding a temple, it can modify its activities to meet the needs of the community, such as organizing festivals or providing religious instruction.

The guthi system stands out as a unique and effective approach to heritage conservation. Its continued use in preserving Nepal’s cultural riches today is a testament to the innovation and forward thinking of the Lichchhavi era.

2.2.2. Malla Period

Nepal reached its cultural and architectural zenith during the Malla period (1200-1768). This period witnessed the preservation of various cultural sites such as temples, monasteries, stupas, water facilities, and irrigation systems through the guthi approach. Evidence of the presence of this system during the Malla or medieval period is evident in numerous inscriptions from that era. In addition, records from the late Malla period refer to several guthis, highlighting their importance in the medieval social landscape including the Guthilok, Gosthisayeba, Gosthi Samuhana, Chintayak Gosthi, Desh Samuchchayena, Ngakuri Dharma Samuha, Panch Samuha, Chaturdashi Guthi Samuha, Dharma Gosthi, Sankranti Guthi Samuha, Sanath Guthi Samuha (Bajracharya, 1999; Shrestha, 2007). In addition, the Panchamahapatak oath included the guthi land grant among its topics, along with five heinous crimes, including the murder of Brahmins or children, adultery, and theft. Most inscriptions emphasize a deep commitment to preserving monuments and historical sites for posterity. In addition, the community was warned that anyone caught stealing land donated by the guthi, whether by themselves or others, would face eternal damnation in hell”(Bajracharya, 1999; Shrestha, 2007).

According to the 1172 Valtol Lalitpur inscription, Lichchhavi customs persisted through the medieval era, especially the practice of safeguarding and maintaining cultural artifacts. The inscription credits Jayachandra, a wise man, with the construction of a resting place, a water spring called Tutedhara or Jaladroni, and a guest house (Pati). Jayachandra contributed funds for the roof of the guesthouse and the maintenance of the road. The locals then requested Agnishala to use the remaining guthi funds for the restoration of the Dakshinvihara Thambu Shribramhapuristhan monastery, according to a 1403 inscription from Thambutol Lalitpur (Bajracharya, 2011)

During the Malla period, the guthi system exhibited significantly higher effectiveness compared to the Lichchhavi period. This was influenced by several factors, including (Chapagain, 2008; Toffin, 1994):

Expansion of the Newar community: The indigenous Newar community of the Kathmandu Valley traditionally managed the guthi system, and their growth in numbers and influence during the Malla era directly affected the size and quantity of guthis.

Rise of urbanism: During the Malla era, the Kathmandu Valley experienced a surge in urbanization. As individuals sought to display their growing wealth and status by constructing temples and monasteries, the demand for cultural objects increased. The guthi system, known for financing and overseeing the maintenance of these buildings, became the perfect solution to meet this demand.

Innovations in Technology: During the Malla era, new technologies such as improved stone-cutting and brickmaking emerged. These advances made it easier to build more elaborate and durable heritage structures. The guthi system’s ability to employ these innovative methods played a key role in ensuring the longevity of the structures it administered.

Overall, the guthi system played a pivotal role in the preservation of cultural heritage throughout the Malla era. Many of the temples, monasteries, and stupas that grace the Kathmandu Valley today owe their survival or renovation to this system, with numerous structures built or restored during this period.

2.2.3. Shah (Modern) Period

The guthi system of safeguarding cultural treasures continued throughout the Shah’s era (1768-present) but underwent specific changes in its implementation. While it originated in the Lichchhavi period and continued through the Malla era, no official guthi offices were established at that time. The Shah era marked the introduction of formalized guthi and government institutions dedicated to heritage management. The establishment of the Guthi Janch Kachahari occurred during King Prithvi Narayan Shah’s unification of Nepal in 1769 and was responsible for overseeing the guthi within the Newar communities. Throughout the Shah era, the guthi land system established by the Malla rulers remained intact (Amatya, 2007; Corporation, 2015; Karki & Singh, 2011; Tandon, 1995, 2020).

The Chhenbhadel Adda, responsible for the preservation of monuments, was officially established in 1798 during the reign of King Rana Bahadur Shah. However, its informal existence dates back to the Malla era in Nepalese culture and was formally recognized and established under the Shah dynasty (Amatya, 2007; Corporation, 2015; Karki & Singh, 2011; Shrestha, 2010; Shrestha, 2008, 2016a; Tandon, 1995, 2020).

Prime Minister Jung Bahadur Rana established the Guthi Bandovasta Adda (Management Office) replacing the Guthi Janch Kachahari, which was responsible for maintaining records of guthi land during their rule. In addition, the Guthi Corporation was established under the Guthi Corporation Act 1976, recognizing the continued existence of the guthi system since ancient times. Notably, the increased involvement of the state in the management of the guthi system marked a significant historical shift, influenced by various factors, including (Amatya, 2007; Tandon, 1995, 2020):

Unification of Nepal: This led to a greater degree of central control over all aspects of society, including the guthi system.

Growth of the bureaucracy: The Shahs created a large bureaucracy to administer their kingdom. This bureaucracy included a department that was responsible for overseeing the guthi system.

Involvement of Newar Community: During the Shah period, the Newar community, historically responsible for managing the guthi system, declined in size and influence, creating a power gap that was filled by the state. As a result, the guthi system became increasingly centralized and bureaucratic, with both positive and negative consequences for heritage conservation.

2.3. Newar, Heritage, and Guthi

Historian Baburam Acharya suggests that the terms "Nevar," "Neval," and "Nevah" share a common origin, "Nepal," linking the etymology of "Newar" to the name of Nepal. Many believe that the Newar community was the original inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley. They stand out as a distinct cultural group in Nepal, speaking a language formally referred to as Nepal Bhasa but commonly known as Newari (Sarveswar & Shakya, 2021). Contrary to popular belief, the Newars are diverse, with most practicing Buddhism, Hinduism, or both. During the Lichchhavi and Malla reigns, Nepal Mandala operated under a system in which community involvement shaped the affairs of the state, facilitated by guthi - a form of self-government. The guthi system has played different roles within the Newar society and has evolved into different types. They are generally classified into three groups based on the goals or purposes of each guthi (Cominelli & Greffe, 2012; Dangol, 2010; Sarveswar & Shakya, 2021; Shakya & Drechsler, 2019a; Toffin, 2005, 2013):

Organizing ceremonial events, religious festivals, caste gatherings, workshops, music, maintenance of water systems, maintenance of rest houses, roads and canals, and other initiatives;

Activities related to the deceased, including managing funerals and related tasks;

Focusing solely on religious activities.

In the Newar community; guthis often unite groups based on caste or family ties, although this isn’t universal. Sometimes they’re formed solely based on geographic proximity (Gerard, 2008; Regmi, 1988; Toffin, 2005). As documented in the literature, these festivals and rituals continue in the very temples, shrines, public spaces, and traditional venues they’ve occupied for centuries. Temples, monuments, stairways, chaityas, courtyards, and stages remain central spaces where art and human interaction converge. In the Newar culture, the guthi system primarily facilitates religious and social engagements (M. Maharjan, 2018; Slusser, 1998).

Cultural heritage encompasses both its products and its ongoing process, providing societies with a rich legacy inherited from the past, created in the present, and passed on for the benefit of the future. Crucially, it encompasses not only tangible aspects but also natural and intangible elements. However, our diverse creativity reminds us that these treasures are fragile and irreplaceable. Therefore, policies and development approaches that protect and celebrate their diversity and distinctiveness are crucial, because once lost, they cannot be recovered (Cominelli & Greffe, 2012; Convention et al., 2019; Maharjan, 2021; Scovazzi, 2019; Sustainability, 2015; Weise, 2012). Today, cultural heritage is intertwined with the critical global issues facing humanity, including climate change, natural disasters (such as biodiversity loss or ensuring access to safe water and food), community conflicts, education, health, migration, urbanization, marginalization, and economic disparities. Therefore, cultural heritage is seen as critical to promoting peace and sustainable social, environmental, and economic progress”(Sustainability, 2015).

In Kathmandu, festivals are held almost daily, and many buildings serve as sacred shrines. Festivals, known as jatras, are deeply woven into daily life here, attracting large local audiences and following the lunar calendar. Each festival has its purpose and style of celebration. Traditional Newari music includes sacred, devotional, seasonal, and folk songs, accompanied by various classical instruments. Various dances, often depicting deities, form an important part of these rituals and festivals. Recognized for its rich cultural, historical, social, and economic facets, Kathmandu Valley is revered as a vibrant city. The local guthi communities play a pivotal role in managing these traditions, underscoring the crucial role of the guthi in preserving this living heritage.

Guthi activities often involve the utilization of caste and regional structures. Until recent decades, a significant portion of employment in Nepal was based on caste (Toffin, 2005, 2007). In the past, people had surnames that reflected their occupation, such as carpenter, farmer, priest, or goldsmith. While these names may still signify past occupations, modern times allow individuals to pursue any profession of their choosing. Although many live outside the historic city walls of the Kathmandu Valley, the guthi continue to maintain family customs. Amidst geographic and occupational shifts based on caste, the guthi system has remained largely consistent, with individuals maintaining their distinct castes and fulfilling their responsibilities accordingly. Numerous guthis required members to perform specific duties for social acceptance. For example, the sana guthi administered funeral rites, while the twa guthi taught music to young men and helped them integrate into the community. Due to the strict nature of these guthis and the modern, independent lifestyles of younger generations, many are distancing themselves from these traditions. Although some guthis continue to maintain substantial membership, several others are adapting their strict membership criteria to the changing times.

Donations were made for a variety of purposes, ranging from minor rituals such as the offering of betel nuts to temples to the staging of major celebrations. The act of donating property was believed to bestow blessings on families for seven generations, illustrating a deep religious commitment. In times of political turmoil, endowments served as a deterrent against land encroachment, which was considered a grave transgression against the guthi. Despite the lack of explicit participant obligations or compensation, the guthi system persisted for generations. Each guthi recognized his or her responsibility in organizing events or maintaining temples. While some guthi have disappeared, the dynamics within these groups continue to evolve. Significant changes occurred around 1769 when the Malla kingdoms allied with the Shah dynasty, reshaping the trajectory of guthi practices. Studies reveal a deep interrelationship between Newar communities, heritage, and the guthi system. Each caste maintains its guthi, preserving its traditions, culture, art, and architecture.

2.4. Heritage conservation responsibilities pre- and post-establishment of the Guthi Corporation

Before the establishment of Guthi Corporation, the overall management, and operation of the entire Kathmandu Valley’s monument/heritage were managed by different 15 offices (Shree 5 Sarkar Guthi Tahasil Paila, Shree 5 Sarkar Guthi Management, Shri 5 Sarkar Guthi Tahasil Doshra, Shree 5 Sarkar Guthi Expenditure, Shree 5 Sarkar Guthi Lagat Check, Shree 3 Sarkar Guthi Management, Shree 3 Sarkar Guthi Tahasil, Shree 3 Sarkar Guthi Making, Shree 3 Sarkar Guthi Dhukuti, Pashupati Goshwara, Pashupati Bhandar Tahawill, Shree 5 Sarkar Guthi Check, Shree 5 Sarkar Guthi Tahabill Section, Machhindra guthi, and Bhaktapur Guthi Expenses) under the different Valley Regional Commissioner and District Offices in the Kathmandu Valley. Each guthi oversees one or more monuments such as temples, Sattals, Patis, and Dharmashala. Each of these monuments has its guthi, which uses donated land to generate financial resources. All tangible and intangible activities are supported by the income generated from the respective guthi lands. In cases where a guthi lacks donated land, its members are responsible for managing financial resources to support its activities (Corporation, 2015; GoN, 1976). These activities illustrate how roles and responsibilities serve as keys to unlock doors. Thus, all guthis have served as the backbone of Nepal’s cultural heritage.

Currently, there are about 2300 state-run (Rajguthi) monuments registered in the Guthi Corporation among the 12000 guthi monuments. Among them are Amanat guthi, which is run by the Guthi Corporation, and Chhut guthi which is run by the respective Matha (Corporation, 2015). Based on the record of Guthi Corporation, there are 69 districts with different types of guthi lands, monasteries, temples, pati, Pauwas, and ponds of different types. Similarly, there are 159 ponds, 647 pati Pauwas, and 717 temples. Rajguthi is present in 650, 301, and 161 Rajguthi in the districts of Kathmandu, Lalitpur, and Bhaktapur respectively. There are 1282 jatras in Kathmandu, 309 in Bhaktapur, and 422 in Lalitpur, all under the supervision of the Guthi Corporation. Guthi Raitan’s designated land is slated for transfer to Guthi Corporation solely as the landowner, comprising 315,472 ropani in the hills and 62,256 bighas in the Terai. Land categorized as guthi Adhinastha, designated for payment to the guthi as Mohi, encompasses 243,607 ropani in the hills and 2,196 bighas in the Terai. Guthi Tainathi land, entirely owned by the corporation, comprises 2,911 ropani in the hills and 1,878 bighas in the Terai region (Corporation, 2015, 2019, 2020, 2021; GoN, 1976; S. R. Subedi, 2022; Subedi & Shrestha, 2023).

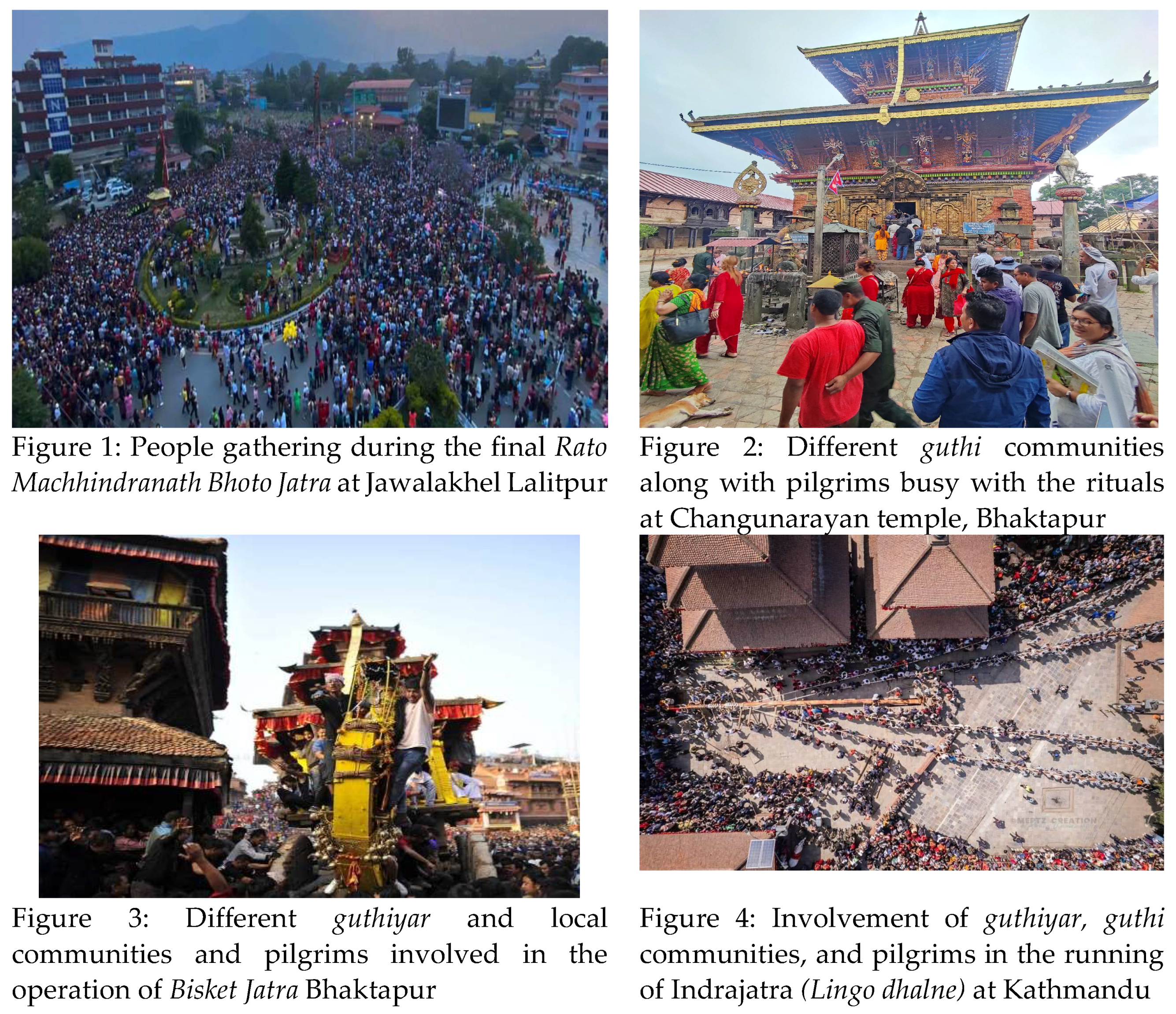

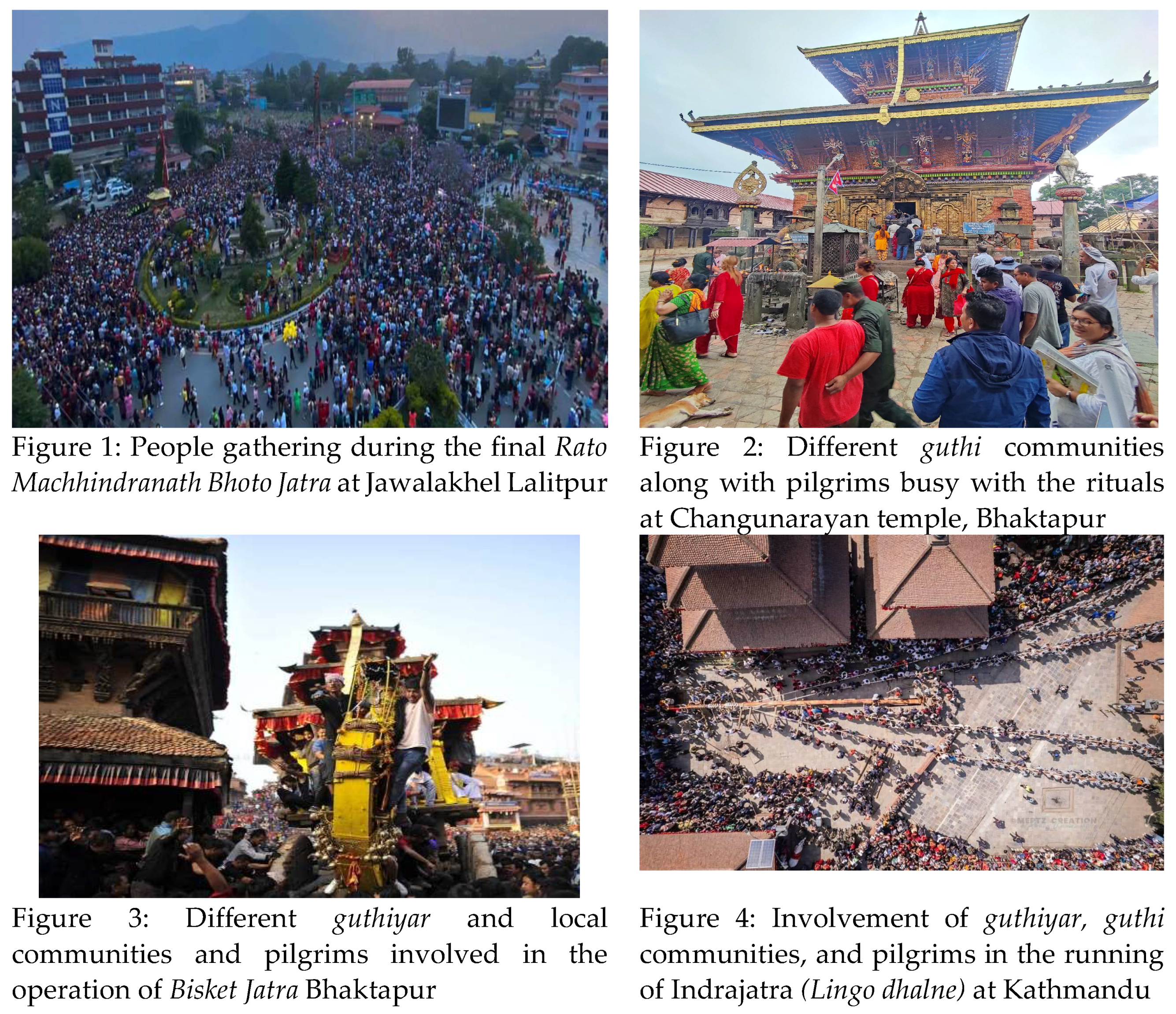

The conservation and management of these Jatras and festivals (Figures 1-4) are carried out by the respective guthis, who, whenever possible, align their activities with the principles of the guthi system (Corporation, 2015; Pujari, 2014). According to the Guthi Corporation’s records, the major list of intangible heritage and guthis function as a case study in the research are given below: Bhimsen Jatra, Pilgrimage of Harisiddhi, Indrajatra, Harisiddhi’s 12-year journey, Khadga Jatra, Thecho Navadurga Jatra, Twelve-year-old Thecho Navadurga Jatra, Khokna Rupayani Jatra, Bhola Ganesh Jatra, Jatra of Bungamati Hygriv Bhairava and Manakamana, Sunakothi Balakumari Jatra, Pilgrimage of Thecho Vramhayani, Lubhu Mahalakshmi Jatra, Vajravarahi Jatra, Bisket Jatra, Gaijatra, Mupatra Indrajatra, Changunarayan Jatra, Bibaha Panchami, Shaileshwori Mela, Bhairavi Jatra,Chame Mela, Chaitra ashain Mela,Planchawok Bhagabati Jatra, Baraha Chhetra Mela, Galeshwor Mela, Hadigaon’s Jatra of Choktenarayan, A journey to find Hadigaon’s jewels, Jatra of Seto Machindranath, Sankhu Vajrayogini pilgrimage, Pharping Harishankar Jatra, Tokha’s Chandeswari Jatra, Journey to Gangamai, Terri Jatra, Guheshwori Jatra, Jatra of Rato Machindranath Jatra, Atal Jatra of Balakumari, Khat Jatra of Balakumari, Chaitra Mahasnan, Sri Taleju Bhavani’s Khat Jatra, and Indrayani Jatra (Corporation, 2015).

In the early days of the guthi system, the focus was on conserving and managing monuments with the income from guthi lands, which serve as a perpetual source of income for Nepal’s cultural heritage. Unfortunately, approximately 65% of the guthi lands have been taken over by various government and non-government agencies without the consent of the Guthi Corporation. According to the records of the Guthi Corporation Act of 1976, the unauthorized use of these lands by the Nepalese government has resulted in unpaid compensation of over thirty billion rupees. Despite this, the compensation remains unpaid. This unpaid amount, coupled with limited income and rising maintenance costs, has created a difficult situation. As a result, the Guthi Corporation faces significant difficulties in properly preserving and managing state-owned monuments (Corporation, 2015, 2019, 2020, 2021; S. R. Subedi, 2022).

The Kathmandu Valley is the most densely populated urban region and one of the fastest-growing urban clusters in South Asia (Muzzini & Aparicio, 2015). The diversity of guthi types throughout history, the impact of government policies, and the evolving interpretations of the term guthi present challenges to their classification. However, for this article, guthi communities will be categorized into three groups based on ownership and management: (a) family-level guthi, (b) private/community guthi, and (c) public guthi (state-run or Rajguthi). Family-level guthis are managed by specific families, while decisions within private guthis involve discussions among senior guthi members (Bajracharya, 1978; Gerard, 2008; March, 2015; Regmi, 2007a; Regmi, 1969; Regmi, 1978; Regmi, 1988; Studies & Studies, 2007; Toffin, 1975; Toffin, 1996, 2005, 2007, 2013).

In each scenario, the administration of the guthi falls under the purview of a select group known as the guthiyar. Designated by specific castes or communities, guthiyars are responsible for overseeing guthi grants, which often involve mystical or confidential rituals in addition to the religious and charitable duties mentioned in the guthi land grants. The main difference between guthiyars and temple officials lies in their roles: while the latter handle and execute the assigned guthi tasks, guthiyars focus solely on administrative and managerial aspects (Gillekens et al., 2017; Kayastha, 2020; March, 2015; Sarveswar & Shakya, 2021; S. R. Subedi, 2022; Subedi & Shrestha, 2023; Von Furer-Haimendorf, 1956). Guthiyars are responsible for collecting rent, selling goods, and procuring supplies needed for religious rituals. They also oversee ongoing guthi events, maintain financial records, handle surplus funds, and facilitate the maintenance of structures such as temples and monuments. Public-level guthis involve a wider range of caste groups in management (Pradhananga et al., 2010). Often, the Guthi Corporation has nationalized public guthis under the Guthi Corporation Act of 1976. Thus, guthis can be described as corporations formed for the establishment and maintenance of charitable and religious institutions, including temples, monasteries, schools, hospitals, orphanages, and homes, along with the observance of religious rites and social traditions (Regmi, 1978; Regmi, 1977).

The link between land ownership and guthis is still strong for proper conservation. Historically, royalty and villagers have donated money, land, and various possessions to guthis seeking spiritual liberation for seven generations (Karki, 2002; Toffin, 2005). Donating land to the guthi was highly valued and considered a social status symbol. In addition, due to the seriousness of confiscating guthi land, such donations have been used throughout Nepal’s history, especially in times of political turmoil, to prevent unilateral state seizure of property (Regmi, 1978). Guthi trusts were established to provide financial stability for successors. They earmarked a portion of the land’s income for charitable and religious purposes, while the rest supported the donor’s family and discouraged future generations from selling the property. In cases where the endowment was financial, the accrued interest was used for religious and charitable obligations. In particular, this included the use of the unpaid labor of cultivators and the collection of rents in goods essential to the prescribed guthi duties (Regmi, 2007a, 2007b; Regmi, 1978).

In addition, the guthi system promoted economic stability by involving the local community in the cultivation of the land and by providing skilled laborers, such as masons and carpenters, for restoration and conservation tasks, thus maintaining and preserving valuable skills essential to the conservation of both tangible and intangible cultural heritage. As described in the previous definition, the continuity of the guthi depended on their access to land. The expansion of religious and charitable groups in the Kathmandu Valley continues to be significantly influenced by these same endowments. By guaranteeing perpetual ownership, prohibiting alienation, ensuring irrevocability, and granting tax exemptions, guthi land ownership became a method for the state to protect religion and ensure a steady, non-transferable flow of funds for various endeavors. These activities included the construction and maintenance of Hindu temples, Buddhist monasteries, rest houses, bridges, roads, libraries, schools, wells, drinking water facilities, and religious institutions (D’Ayala & Bajracharya, 2003; Gerard, 2008; M. C. Regmi, 1976; Mahesh Chandra Regmi, 1976; Regmi, 1988; Toffin, 2005, 2007; Vajracharya, 1998)

3. Result and Discussion

Research shows that the guthi system in Nepal is facing increasing challenges due to government policies that don’t support the traditional land tenure system. To remain relevant, the guthi system must adapt to the changing cultural landscape. Initially, urban life prioritized the preservation of cultural heritage, with socio-religious and political systems focusing on the construction and maintenance of monuments. These practices have now become ingrained in the current lifestyles and rituals of the population (Maharjan, 2021; Nepal & Marasini, 2018; Regmi, 1965; Regmi, 1968; R. S. Subedi, 2022a, 2022b; S. R. Subedi, 2022; Subedi & Shrestha, 2023).

The creation of local "guthi" groups was a wise move to protect monuments. While traditional festivals continue in the Kathmandu Valley and guthi members are dedicated to maintaining temples, Nepal’s official heritage preservation doesn’t fully recognize these ancient practices. The guthi system has a long history of community involvement in historic preservation, suggesting the importance of improving current methods rather than introducing entirely new conservation efforts (Gillekens et al., 2017; Kayastha, 2020; March, 2015; Sarveswar & Shakya, 2021; S. R. Subedi, 2022; Subedi & Shrestha, 2023; Toffin, 2014; Von Furer-Haimendorf, 1956).

A key observation highlights the separation between traditional community-driven conservation and formal heritage conservation, signaling a lack of full integration. The key issue revolves around the timely recognition of the intrinsic value of the guthi system, especially in the face of the evolving Nepali culture. Urgent measures are needed to recognize and protect the guthi system to prevent its erosion amidst the waves of modernization (Chapagain, 2008; Dangol, 2010; Nations, 2013; Scott, 2019).

Numerous guthi communities and various stakeholders have been actively involved in the preservation and monitoring of the cultural heritage of the Kathmandu Valley and surrounding regions. Throughout the Lichchhavi to Malla periods, the lack of written rules or regulations resulted in many communities losing indigenous systems, inscriptions, traditions, and customs due to inadequate mechanisms and human resources. To preserve these invaluable cultural legacies, the government must establish rules and procedures.

Discussions with guthiyars, residents, and stakeholders highlight the indispensable role of various guthi communities in preserving all facets of the intangible heritage. Field studies indicate the involvement of over a dozen different guthi groups in various roles and responsibilities outlined by the guthi archive for initiating rituals and traditions during various festivals like Indrajatra, Biska Jatra, Rato/Seto Machhindranath Chariot, Hadigaun Jatra, Shivaratri, among others. The financial support for these chariots, festivals, rituals, and customs comes from the related guthi revenue, which underlines the pivotal role of guthi in the effective preservation and management of cultural heritage.

The research results show that to successfully conserve and maintain cultural assets through traditional management systems like guthi, it is necessary to assess current regulations and coordinate efforts. Analysis of systems in various continents, including Europe, America, and Africa, shows how special it is for ancestors to provide resources, such as donated land, for the upkeep and preservation of cultural landmarks (DeGeorges & Reilly, 2009; Martínez, 2016; Throsby, 2016; Turner, 2013). In the end, the study confirms that guthi plays a significant role in guaranteeing the sustainability of cultural property management and protection.