Introduction

Achieving sustainable development will require effective water management, but the main framework for it, Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), lacks clarity and the acceptance needed for policy, planning, and decision making. IWRM is the best-known comprehensive approach to water management, but its ambiguities and uncertainties in applications call into question whether a unified approach can succeed [

1]. To be effective, such management approaches require assessments of the state and the uses of water, as well as their interactions with other natural resources, society, and the economy. Without clarity in IWRM or water resources assessments, the possibility to advance water resources sustainability is limited because decision makers need clear and compelling information to take appropriate actions.

Water resources assessment is a key process of IWRM [

2], but methods for it are not institutionalized and it is used in different ways. It involves different contextual situations, and assessment teams must create individual approaches, often without much guidance. Evidence can be seen by lack of a management instrument for water resources assessment in the IWRM toolbox of the Global Water Partnership [

3]. This is despite advocacy to advance water resources assessment to promote the global sustainability agenda [

4,

5,

6].

Meanwhile, climate change and human activities are causing heavy impacts on economies and societies around the world, as well as on the natural hydrologic cycle [

7]. Reports like this and their calls for action to improve sustainability of water resources are common, but progress has been difficult and this leads to pessimism about achieving most Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

8].

The challenges to improved water management are formidable and include competing demands for water resources and governance problems at a range of basin and jurisdictional scales [

9]. The assessment reports from global organizations like those in the UN system are necessarily based on aggregations of country data, which will vary markedly in quality and reliability. The country level is appropriate to prepare water resources assessments for nation scale units, but they are more complex for large countries than for smaller ones.

After the 1992 Earth Summit [

4], the seeds were planted to develop the concept of IWRM to address the economic, social, and environmental aspects of water resources sustainability. Its application should be in a cycle from establishment of national goals to water resources assessment and policy development, to implementation of necessary actions [

2]. However, as compared to the established field of environmental assessment [

10], water resources assessment lacks a distinct methodology or legal requirements.

This paper addresses this lack of a definite structure and recognition for water resources assessment, which poses a dilemma because it is essential for progress toward sustainability. The analysis is embedded in questions about the effectiveness of IWRM itself and needs for improvement in overall approaches to water resources management. The first part of the paper explains the processes and applications of water resources assessment and links them to management activities of IWRM. Examples of applications illustrate how and why water resources assessment is needed in varied situations. Based on the examples, the paper describes the nuances of applying assessments among the many scenarios possible in IWRM. The paper also outlines difficulties and challenges of performing effective assessments and offers agendas for research and development and communication to promote improved approaches. Suggestions are made for roles and responsibilities of stakeholders to confront the difficulties and advance the methods of water resources assessment toward the goals of improving IWRM and water resources sustainability.

Water Resources Sustainability, Management, and Assessment

The concept of sustainability assessment provides context to discuss water resources assessment and management. Regardless of how it is defined, sustainability is inherently a systemic notion involving a hierarchy of systems. In a practical sense, it involves the uses of resources as well as their supply and condition. This is evident from the 17 SDGs, all of which address needs such as hunger, poverty, and health, and water resources sustainability is a core issue in them. The systemic nature of sustainability is seen in the sectorial aspects of the SDGs, as examples show, such as Zero Hunger aiming at the food sector, Clean Water and Sanitation at the water sector, and Life Below Water at the fisheries sector [

11].

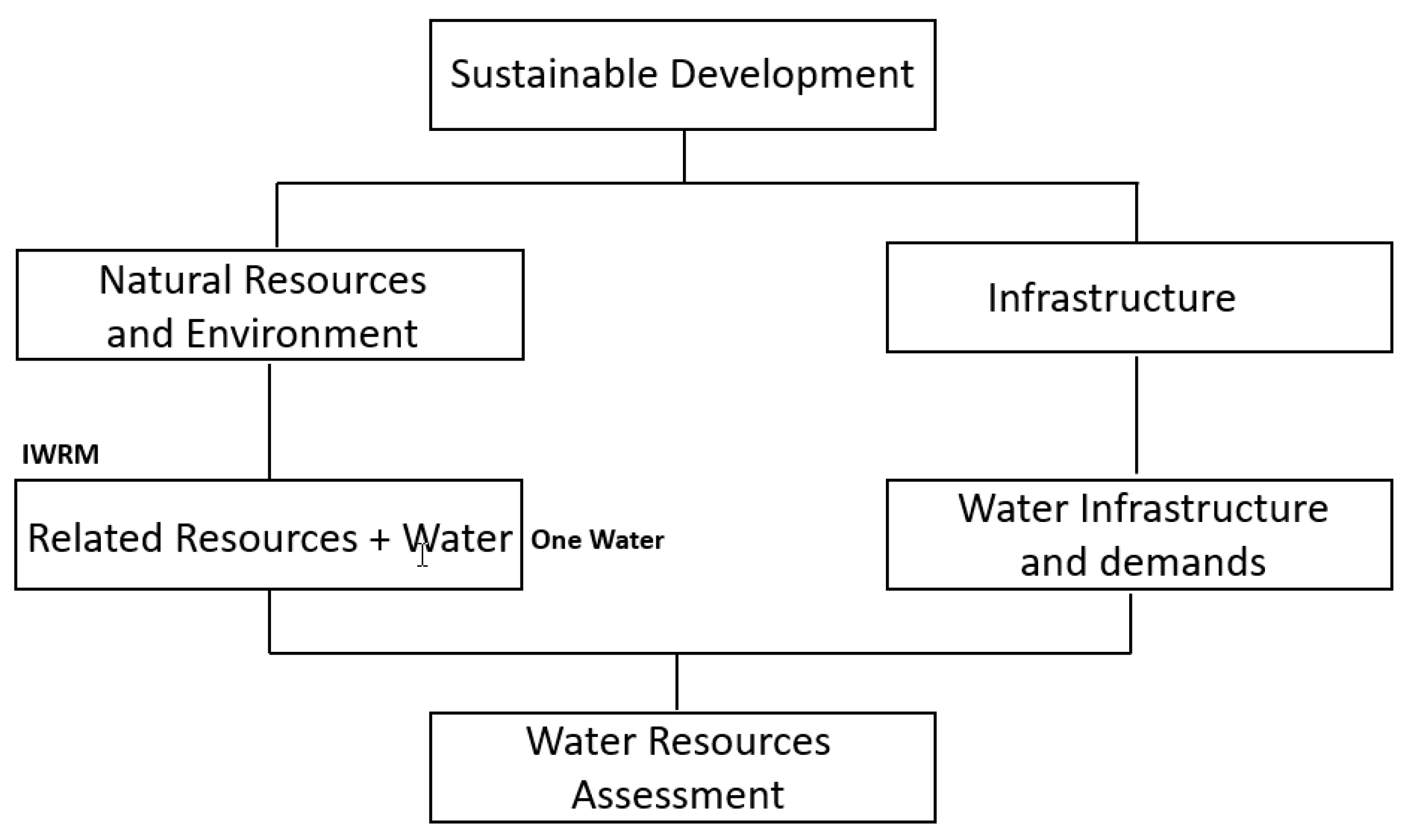

The systemic nature of sustainability lends itself to a model with a hierarchy beginning at the topic with sustainable development at the top and the 17 SDGs one level down. Each of them is cross-sectorial, as shown, for example, by Good Health and Well-Being, which are related to poverty, hunger, water and sanitation, and other SDG categories. Another level is formed if the SDG categories are parsed to show separate sectors.

Figure 1 shows this hierarchy developed for water resources and their assessment. At level two, natural resources, environment, and infrastructure are identified as categories where condition and capacity to meet needs should be assessed. The next level shows water resources and water infrastructure as distinct categories, with related resources next to water to demonstrate how IWRM addresses sustainability. The term One Water is shown next to the water box to illustrate how its community uses it to indicate all water types [

12]. The lower box illustrates how water resources assessment involves a combination of water and the status of its infrastructure and uses.

Performing assessments at each of these levels will involve complex sets of indicators. A generalized view might begin with the interacting natural and human worlds at the top [

13]. To address these and measure sustainability with indicators, the involved authority must define the boundaries of the system of interest. For example, for a state government, Western Australia has a sustainability plan for all sectors in the state [

14]. The California Department of Water Resources has a plan for water sustainability indicators within the state, which fits into an overall framework for forests, rangelands, and water [

15,

16,

17]. These indicators frame the general concept of water resources sustainability in terms of supply reliability, water quality, ecosystem health, and social equity, along with an adaptive and sustainable management system.

The parallel aspects if water as a liquid and as the provision for natural and human needs, give the term water resources a dual scope which is evident in the water cycle’s paths through water bodies and links to other renewable natural resources and to human uses of water. IWRM requires assessments of these dual aspects, the state of the water itself, as measured by extent (amount and distribution) and condition (physical, chemical, and biological attributes) in various settings, as well as whether the resources are meeting demands [

18].

Sustainability of the extent and condition of water resources and their capacity to meet needs requires successful planning, management, and regulation, and these are driven by policies that are developed within the relevant governance structures. These management processes require a comprehensive framework to organize them and provide the necessary decision information, including through water resources assessment.

Several proposals for a comprehensive framework for water resources management have been developed, and the term with most traction is IWRM. The most quoted definition of it shows its link to sustainability: “a process which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources, in order to maximize the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems” [

19].

If the broader IWRM community is thought of as an organization, it has become a holding company for many diverse water resources management programs. This creates communication problems that stem back to the broad nature of water resources. Lumping them into a single category this way serves program organization and the interests of some stakeholders, but it obscures issues that people care about like drinking water and pollution prevention.

As mentioned, the requirement for water resources assessment in IWRM comes just after national goals and policy setting [

2]. It can be defined by inserting the phrase water resources into the definition of assessment, the “act of judging or deciding the amount, value, quality, or importance of something…” [

20]. This works in other examples as well, such as educational assessment, which has its own journal [

21], and environmental assessment, which also has a large body of knowledge [

10]. The difficult part is to develop the standards against which to judge. Unless a standard is set, the observations about value, quality, and importance cannot be made. Educational and environmental assessment have clearer standards than water resources assessment has, which helps explain their greater acceptance.

Environmental assessment includes water issues, and it has a large body of literature and experience. It uses expert judgements and evidence to provide credible answers to policy-relevant questions. To provide these, it uses estimation, evaluation, or prediction of the effects of natural processes and human activities on the environment. The policy-related needs require objective evaluation of data and information to meet the needs of users and support decision making [

22].

Although water resources assessment is related to environmental assessment, it requires its own procedures. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) explained its dual aspects as the determination of sources, extent, dependability, and quality of water resources, considering their utilization and control [

23]. Whereas environmental assessment focuses on decision-making about impacts of actions on the environment, water resources assessment is not used primarily to evaluate impacts of proposed actions and focuses on the adequacy of the resource and whether it can meet all needs.

In the United States, the need for water data and assessment methods was recognized when the US Geological Survey was established before 1900 [

5,

24]. Not every nation has such a data and assessment agency, and this lack has been an international concern because national databases are vital to water resources assessment and to mitigation of the negative effects of floods, droughts, decertification, and pollution. Barriers to establishment of such agencies are due to lack of financial resources, fragmented nature of hydrologic services, and workforce limits. [

4]

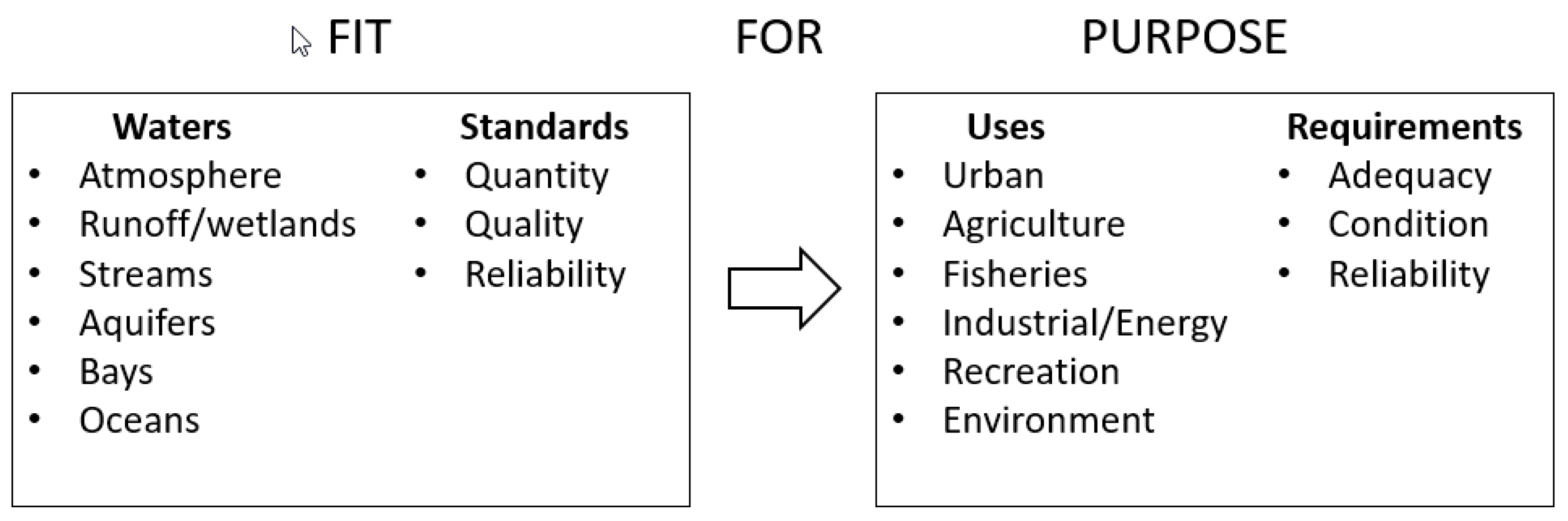

While long definitions and explanations of water resources assessment are common, the short phrase “fit for purpose” captures the concept [

25]. Fit for purpose assessments are used broadly in education and workforce management [

26], and for water resources, the comparable question is, will the water resources do what they are intended to do? The dual nature of water resources assessment is revealed by the question because the “will they do” part requires data on extent, condition, and reliability, and the “what they are intended to do” part addresses water use requirements.

A general model based on the fit for purpose concept could provide a comprehensive view of water resources assessment for use in IWRM (

Figure 2). The condition of water is in the box under “fit,” and that short word captures both the different forms of water and their condition, based on standards that should be set. The box under “purpose” indicates how the adequacy, condition, and reliability of water for the diverse uses can be measured.

IWRM focuses on coordinated management of water, land, and other resources, and the part of it concerned most directly with water will focus on the water itself and related infrastructure. This management begins with tasks to operate structures and equipment and extend upward to decisions about water allocation, diversion, and treatment [

27]. Water resources assessment will be needed at different levels and stages of governance and management, as in policy, planning, organization, implementation, operations, regulation, and renewal.

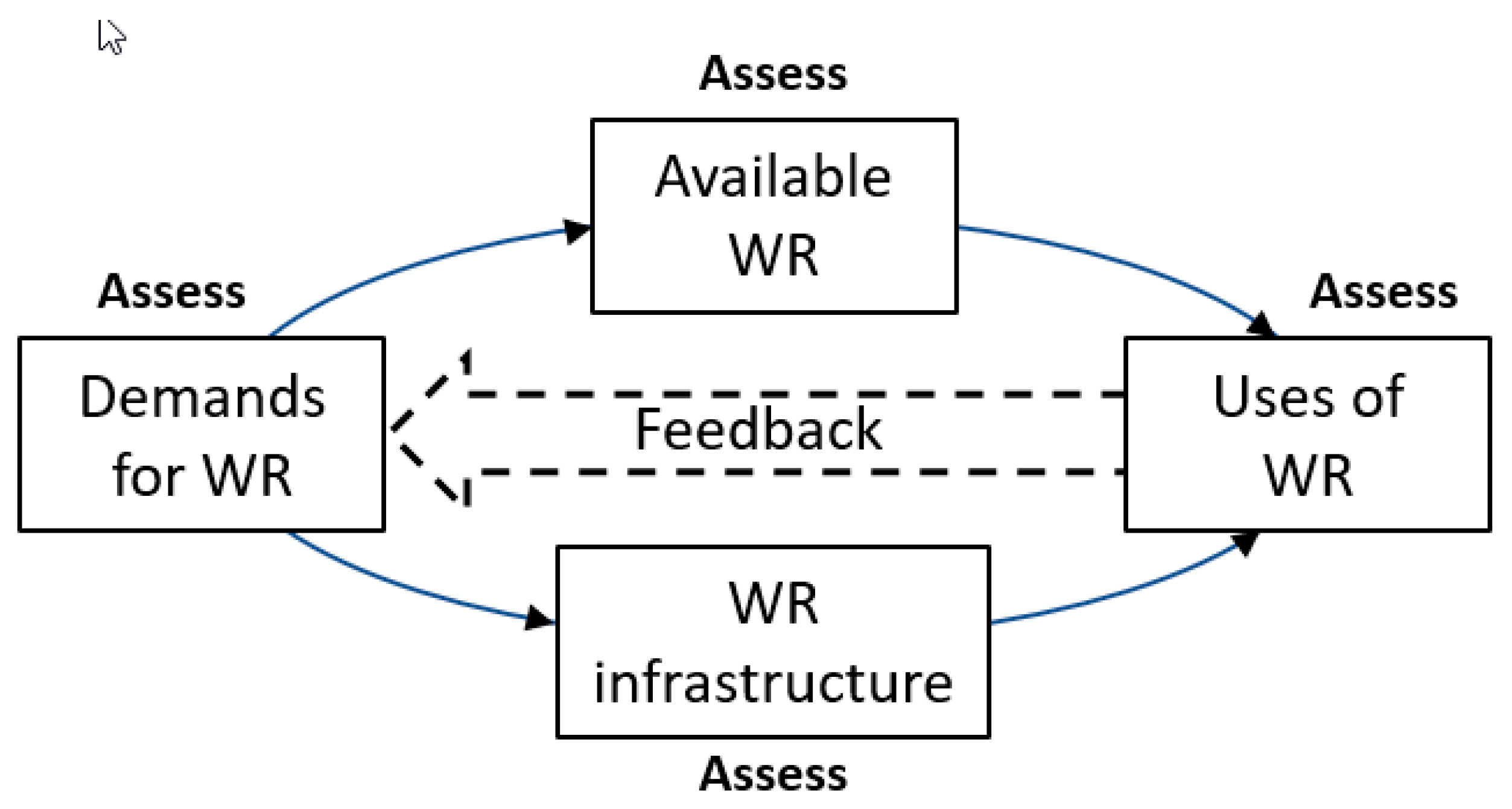

Figure 3 shows a general view of the dual nature of water resources assessment and its multifaceted roles in management. Water resources management begins with demands for water resources, whether liquid water, hydropower, or other uses for water by the various sectors. These demands and requirements must be assessed to determine their causes and priorities. The assessments of the available water resources and infrastructure must show if they can meet the demands and are sustainable. The end uses of water resources must be assessed and checked against the demands to see the balance and to determine if they meet the goals of IWRM to “… maximize the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems.” [

19] For example, if uses show losses and waste, that information should be used to modify the demands.

Water Resources Assessment across Scenarios

While as

Figure 3 illustrates, water resources assessment is used in different ways, the main dialogue about it in the IWRM arena is about use at the national level. The reason for this is that as the IWRM methodology developed, its focus was on establishing water policy, organizations, and governance structures at the national level in countries where water resources management is not well established [

4,

6]. However, IWRM involves many scenarios, which are demonstrated by the diverse case studies available. For example, the Global Water Partnership (GWP) currently lists more than 250 cases with diverse topics and governance situations [

28]. While none of the GWP cases address water resources assessment as a main subject, it is embedded in many of them. This can be shown by examples of how water resources assessment is used for different purposes at different geographic and jurisdictional scales. The examples are organized as policy, planning, project development and operations, and regulation categories.

The impact of policy on water resources sustainability is greatest at the national level, and water resources assessments are a basic and essential input in policy development. This is evident across the natural resource sectors because sustainability in all of them is a critical issue. An example is the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974, which called for assessments of renewable resources on all forests and rangelands in the US. [

29] Water is embedded in the environmental sector, and the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has a designated organization to develop the science for a range of assessments [

30]. Within this activity, USEPA scientists perform surveys of the condition of streams nationwide to track their condition.

The need for water resources assessment was institutionalized in US Water Resources Planning Act (WRPA) of 1965, which required assessments by a newly formed Water Resources Council of the adequacy of water supplies to meet requirements in each water resource region of the nation. [

31]. The assessments focused on economic concerns more than on the broad notion of sustainability, which had not developed to the extent it has today. The Water Resources Council has been dismantled, but the US Geological Survey (USGS) has since published National Water Summaries to improve public understanding, which helps to support positive policy development [

32].

Water resources policies are set at the state and local levels as well. State framework studies require assessments in the early stages of planning processes. The WRPA authorized states to prepare these, and each would have an initial section outlining its water resources, their condition, and the needs. In a more recent example, the Louisiana Statewide Water Resources Framework sponsored a water resources assessment with a focus on sustainability and energy management [

33]. The same approach is seen in framework plans of other nations. For example, countries in Latin America typically have national water framework plans, which outline needs and strategies [

34,

35].

For example, at the local level, assessing resources and their depletion is needed to set policy for supply availability and to plan for drought. Studies are conducted by water supply agencies, such as in the author’s local City of Fort Collins, which has a water supply and demand policy that was based on extensive study of supplies and demands [

36].

Use of water resources assessment is also evident in river basin planning, which establishes coordination among stakeholders in basins to determine requirements and compare them to the status of water resources. A prominent example is provided by the Mekong River Commission for Sustainable Development, which has been in operation since 1957 [

36].

Water resources assessments have multiple uses for planning, project development, and operations with a focus on needs and resources available. A recent example is the World Bank’s approval of a water and sanitation project in Cambodia [

37]. To address needs in water and sanitation, the assessment will focus on the status and condition of the resources available and the unmet needs. At the operations stage of projects, planning is needed to address results of past actions and to address future needs. Assessments are needed in the same way as in other uses of planning because any plans require knowledge of how the facilities will be operated. An example is provided by the annual operating plans of the USACE on the Missouri River [

38]. In this case, extensive assessment information is provided for the public and stakeholders as many are involved.

Regulatory policies and actions require water resources assessments because the problems to be addressed represent non-sustainable practices. An example is the ongoing stream assessments by the USEPA, which collect data from states and combine it with other surveys and studies to develop a comprehensive picture that can inform regulatory policy. State contributions to the national assessments are required by the Clean Water Act [

39]. States respond with their individual programs for water resources planning and assessment [

40].

Challenges to IWRM and Water Resources Assessment

The discussion has shown that water resources face many pressures and emerging problems, that management must be improved, and that definite roles for water resources assessment are needed to establish needs for and conditions of the resources. IWRM provides a recognized way to improve management to address the issues, but it is a broad and somewhat vague notion and not well established. This affects the messaging and acceptance by the public and policy makers [

41,

42].

Regardless of its name, the concept of a comprehensive approach to water resources management has had continuing problems of definition [

27]. This can be called a “conflicting sectors” problem and raises the question of whether water resources management merits a separate focus as opposed to other natural resources and environmental fields. IWRM is such a broad concept that it can only be clarified at the levels of its constituent parts and in examples with case studies, which can be organized to show common patterns and lessons.

If IWRM is not well accepted, the recognition of water resources assessment will also be lacking [

43,

44,

45,

46]. This lack of acceptance of IWRM and water resources assessment saps support for data collection and assessment programs. This problem was identified three decades ago in the preparation for the Earth Summit and led to its inclusion in Agenda 21 [

6]. This occurred as IWRM was in its early stages and it seems certain that today the recommendation would advocate assessment within the framework of IWRM.

Like IWRM, the ambiguity of the term water resources assessment hinders its acceptance as a distinct practice. Availability of alternative language like water balance or water accounting would only add to the problem. This challenge does not confront assessment in the educational or environmental spheres because there are definite uses for the results, often with strong legal controls. Use of the phrase fit for purpose offers a way to reduce ambiguity by asking clearly if the water resources will do what they are intended to do.

The large number of parameters involved in sustainability assessments in the natural resources and environmental sectors causes complexity. Water resources assessment has the same problem, and in addition to ambiguity, it suffers from the same problem that afflicts sustainability assessments, the complex multi-dimensionality [

47]. This creates issues in determination of standards and reaching agreement on performance indicators, which harms the application of IWRM.

The “conflicting sectors” problem exacerbates stovepipes, hinders coordination, and poses barriers to assessment becoming recognized as a distinct process. The establishment of the Water Resources Council in the US was meant to address this issue at the federal level, but the agency was abolished due to differing policy agendas [

48]. Framework studies at the state level and the national water plans of small countries provide a more manageable scale than large countries for assessing water resources sustainability. Regardless of scale, focal points for monitoring, assessing, and reporting water resources sustainability are needed to support policy and planning.

The problem of stovepipes also afflicts data collection and management. The US had a federal coordinating council for data, but it has been terminated [

49]. Coordination for water data is now centered in USGS, which is the main source of most water data among federal agencies [

50]. That agency will have a challenge to coordinate data programs across all the water subsectors.

Considering complexity, ambiguity, and stakeholder fragmentation, lack of acceptance of IWRM and water resources assessment as definite and recognized procedures is understandable. As both are essential for water resources sustainability, a path forward should indicate what it is necessary to do, how to do it, and who should be involved.

Advancing IWRM and Water Resources Assessment

Ultimately, dialogues about specialized topics like IWRM and water resources assessment will make little impact in the broader world of action without specific actions. Most important is to advance water resources management while presenting the case for action in terms that people care about, like drinking water, stream health, flood risk, food supply, and the price of housing. The public messaging must be changed, as was illustrated by the advocacy by Biswas [

41] and his dialogue with Prime Minister Gandhi of India.

In terms of nuts and bolts, water resources managers should clarify their own language about IWRM and its variants, as well as to be clear about levels and types of applications. Methods of water resources assessment should be clarified to support IWRM at all levels and to offer stakeholders methods that they can understand and apply. The fit for purpose approach offers possibilities, and it can be linked to the levels and applications of IWRM. The Global Water Partnership could help by adding water resources assessment to its list of management instruments.

Government stovepipes must be addressed to promote coordination. The different types of assessments should be integrated to focus on how water resources meet needs. The US Water Resources Council was to do that, but it has been disbanded and a new approach is needed. USGS is assigned to coordinate water data across agencies, but it lacks a mandate to prepare a comprehensive national water assessment.

Joint work between the advocates of water resources assessment and the water resources management community is needed to develop a plan. Researchers can be involved in advancement of both water resources management and assessment as interdisciplinary matters. The policy community will be a primary user of the outcomes and should have a role, along with practitioners of water resources management who will use them. Water industry media outlets have essential roles to carry the messages to the water resources community.

Conclusions

Many drivers are affecting water resources and causing severe impacts on the environment, economies, and societies globally. Despite their aspirations, progress has been difficult in achieving most sustainable development goals and improved water management is needed globally. As a framework for this, IWRM has been under development for several decades. Whether the water resources management framework is IWRM or called by another name, the process of water resources assessment must be a key component, but it lacks a definite structure and methodology.

As a subset of sustainability assessment, water resources assessment can benefit from a large body of knowledge. The difficulty is to drill down through the subprocesses of water resources management to find suitable focal points to apply assessment results. Once these are identified, standards against which to judge sustainability are needed.

The standards needed will be difficult to determine on a general basis. Globally, water resources sustainability reports are based on aggregations of country data, which will vary in type and credibility. Within countries, water resources assessments have uses for planning, project life cycles, and regulation, but its impact on policy for sustainability is greatest at their national levels. Large countries like the US have difficulty in assessment due to their heterogeneity, but smaller countries and states can provide effective reporting units.

Acceptance of IWRM and water resources assessment as definite and recognized procedures is needed, and decisions are needed about what to do, why to do it, how to do it, and who should be involved. What to do is to advance the methodologies and recognition of both IWRM and water resources assessment. The reason is to improve water management at all levels by offering stakeholders methods that they can understand and apply. The path forward is to simplify, clarify, and focus on the most important uses of water resources assessment. The fit for purpose approach offers a way to do this. Then, the concepts should be communicated to stakeholders through the appropriate channels.

Ultimately, the benefits to sustainable development from improved acceptance of IWRM and water resources assessment methods can be substantial, but clarity and better communication with stakeholders are critical if progress is to be made. Advocates of water resources assessment and management can lead in working on this. Researchers can be involved, and the policy community should have a role, along with practitioners of water resources management. Water industry media outlets also have essential roles.

Even without a major crisis, a comprehensive and coordinated approach to water resources management and assessment must take into account the incremental losses in sustainable development when fragmented approaches are taken. Effective coordination is needed to clarify problems and approaches and to improve messaging to the public.