4. Discussion

In captivity, female Julia Creek dunnarts become sexually mature between 17-27 weeks and males between 28-31 weeks [

4]. Similar to other dasyurids, dunnarts have evolved reproductive strategies to maximize fitness within their short life spans (2-3 years) such as: being seasonally polyestrous, avoidance of semelparity (rapid senescence and death after first breeding season as in Antechinus sp.), having a spontaneous ovulation, multiparity and the ability to store sperm; unique amongst marsupials [

12,

13]. In addition, in situ surveys have also found that Julia Creek dunnarts can raise two litters in an extended breeding season, which is a common reproductive trait in species inhabiting semi-arid ecosystems where food availability is unpredictable [

4]. Despite these adaptations, captive dunnarts unable to breed rapidly attain senescence, increasing their vulnerability to aging-associated conditions as observed in this study. Photoperiod cues could offer some insight into reproductive failure particularly in male dasyurids. As photoperiod increases in the southern hemisphere, plasma cortisol levels do so as well, negatively influencing spermatogenesis [

14]. Mortality coincides in certain dasyurids with elevated post-mating plasma cortisol levels as well as a testosterone-dependent, post-mating decrease in plasma corticosteroid-binding globulin. Such reproductive strategy might bring positive, short-term reproductive effort benefits for species evolved to have few mating encounters, via increasing energy mobilisation. However, it can also induce fatal syndromes resulting in anaemia, anorexia, hippocampal neuronal apoptosis, increased vulnerability to parasitic and bacterial infections, decreased splenic follicle size, amongst other issues. The role of reproduction in post-mating morbidity and mortality is further supported by the significant increase in lifespan upon castration or pre-mating removal of males [

14].

Susceptibility to age- and non-age-related hyperplasias, benign and malignant tumors vary considerably between marsupials or dasyurids. Interestingly and according to the literature, dasyurids are overrepresented in terms of neoplastic disease compared to other mammals, with one study reporting an incidence of 46% in this family [

10] compared to 2-10% reported for other mammals [

15]. None of the reported tumors of high incidence in dasyurids or other marsupials such as adenocarcinomas, mammary carcinomas, trichoepitheliomas, squamous cell carcinomas, hemangiomas or hemangiosarcomas, and hepatic adenomas were observed in this study, with the exception of lymphoma [

14,

16] and one case of a fibrosarcoma in a hind limb (not included in this study). Neoplasia in Julia Creek dunnarts was only represented by multiple cutaneous lymphomas and a uterine adenoma. Additionally, the literature reports degenerative conditions in geriatric dasyurids primarily affecting nervous or musculoskeletal system. Aged quolls (Dasyurus sp.) and Tasmanian devils, Sarcophilus harrisii (>3 years old) acquire progressive leukoencephalopathies, myelopathies and intervertebral disc disease [

17]; these were not observed in the dunnarts in this study.

It is important to note that the present study had a relatively small sample size and unfortunately not all dunnarts received a thorough postmortem examination with histopathology. These factors could have negatively influenced our ability to have a more accurate demonstration of geriatric dunnart diseases. Nonetheless, the literature on dunnart diseases is very limited compared to other marsupials. This fact is not surprising as diseases are not considered a significant threat to dunnart conservation, compared to other dasyurids with well-studied diseases such as the case with Tasmanian devils, [

18] or other marsupials, such as koalas, Phascolarctos cinereus [

19]. This fact has understandably re-directed research efforts into mapping conservation-priority habitat or answering ecology or biology questions [

4,

7,

12,

20]. A few studies regarding naturally-occurring disease in captive fat-tailed dunnarts (S. crassicaudata) documented dermal spindle cell tumors, splenic lymphomas, squamous cell carcinomas and round cell sarcomas of the upper limb [

10], whilst others stressed the vulnerability of captive dunnarts to reverse transmission of zoonotic pathogens, when human-derived Helicobacter pylori infection resulted in an outbreak of gastric bleeding and weight loss [

21]. The cause of the high incidence of neoplasia is currently unknown but genetic predisposition to lymphoma has been suggested in fat-tailed dunnarts, which grants further exploration of this question in dunnart species [

10].

Little information is available in peer-review literature on ovarian tumors in marsupials or more specifically, dasyurids, with scattered reports of ovarian hemangiomas and adenocarcinomas in quolls and koalas [

22,

23]. Most of the lesions found in the female reproductive tract of these dunnarts are considered degenerative changes, namely CEH and cystic oviduct which, as in other species, is associated to long-term exposure to female reproductive hormones in non-castrated animals [

24]. Interestingly, this prolonged exposure is also a risk factor for mammary neoplasia, which was not observed in this study despite being reported in other marsupials [

16,

25]. The reasons behind this discrepancy are unknown. It is worth noting that in our study, there were 5 of 11 female dunnarts that did not meet the inclusion criteria (autopsy at NWT&R with no histopathology) also had gross ovarian lesions (dunnarts 134, 159, 170, 200), illustrating the high frequency of reproductive lesions in this colony.

As reported elsewhere in possums [

16,

23], CGH was the most common disorder of growth in aged female dunnarts, as in aged rabbits, mice, rats and dogs [

26,

27,

28]. Uterine cysts and uterine metaplasia has also been reported in mature grey short-tailed possums (Monodelphis domestica) [

29]. Malignant neoplasia appears to be of common occurrence in marsupial literature [

10,

30] and from these, carcinomas occur but are more often associated to other tissues (e.g. pulmonary, mammary gland) rather than endometrium [

16,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Interestingly, primary malignant reproductive neoplasia was not observed in this study and likewise, it was found to not be the major cause of death in a captive colony of endangered mountain pygmy-possum (Burramys parvus), the report focusing instead on progressive renal disease [

25]. Endometrial carcinomas are uncommon in animals except for the rabbit, cattle and certain rat strains. Multiple parallels regarding reproduction have been identified between rabbits and dunnarts which might provide insights into the pathogenesis of reproductive disorders in dunnarts. The two most common uterine disorders in rabbits are adenocarcinomas – affecting rabbits at any age and commonly resulting in pulmonary metastases - and CGH, with endometrial inflammation being uncommon [

34,

35]. CGH was the only entity frequently observed in this study. Notably, vaginal serosanguineous discharge and abdominal distension were frequent clinical findings in captive Julia Creek dunnarts with CGH and are also observed in rabbits with adenocarcinoma [

35,

36]; thus, it is recommended that any future captive breeding attempt in the species incorporates frequent checkups for either of these two clinical signs, with culling being a suitable endpoint. Ovariohysterectomy is the only successful treatment to date, with an overall post-surgical survival of 80% in rabbits [

35]; however, this would not be a viable treatment option for a captive breeding colony, where fertility is important. In rabbits with endometrial adenocarcinoma, the non-carcinomatous foci in the endometrium have evidence of CGH, suggesting an association with hyperestrogenism. As induced ovulators, both rabbits and dunnarts can have quite prolonged estrus and experience little luteal activity, bringing a persisting estrogen:progesterone ratio favoring estrogens [

37]. At least in the rabbit, there is evidence of CGH evolving to malignant anaplastic carcinoma [

36] so it is unknown if given sufficient time, the CGH dunnart cases would have turned malignant. Future research in this area evaluating the degree of hormone dependence of endometrial carcinomas and CGH could help in understanding the pathogenesis of spontaneous proliferative reproductive disorders in dunnarts.

Both cases of neutrophilic infiltration in cervix and vagina could suggest an acute ascending bacterial infection - despite bacteria not observed on histopathology – or alternatively, their presence is possibly contingent to the phase of the ovarian cycle. Vaginal and cervical inflammation have been reported before in marsupials, mostly due to ascending bacterial infections from the cloaca (site of convergence for urogenital and alimentary tract) or due to tears during mating with an overly aggressive male [

38]. Equally, the presence of granulocytes/neutrophils – along cornified and nucleated epithelial cells – in vaginal and cervical segments is a normal finding in mice and rats during metestrus and diestrus, serving as an arm of localised innate immunity and assisting when staging vaginal smears [

39,

40]. It is unknown to the authors if the dasyurid ovarian cycle behaves similarly to rodents. Literature on the cellular reproductive profile in other marsupials (e.g. Tasmanian rat-kangaroo (Potorus tridmtylus) [

41], Common brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) [

42] suggests the ovarian cyclic phase might influence rodents and marsupials in a similar fashion. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that both female dunnarts in which neutrophilic infiltration was observed had concurrent CGH and evidence of anovulatory ovaries, which may favour a pathologic cause for neutrophilic recruitment.

Cases of testicular degeneration are consistent with advanced age as reported elsewhere in other aged male marsupials [

29]. In one case (dunnart 9), the left testicle was unilaterally enlarged, necrotic, and with a diffusely edematous tunica albuginea, suggesting that the necrosis was secondary to impaired thermoregulation [

43]. Testicular atrophy is seen as an advanced state of degeneration, with mineralization and fibrosis. Causes are multiple, however intrinsically, aging is a well-recognized predisposing factor in all species, probably due to degenerative vascular lesions in testis or pampiniform plexus [

43]. Aggregates of interstitial (Leydig) cells were observed in one case of testicular degeneration with concurrent seminiferous tubular loss and replacement by granulomas within a background of autolysis. It is possible that the loss of tubular profiles mimicked interstitial cell hyperplasia, a recognized phenomenon in aged animals with or without atrophied testes. If the cellular proliferation was a real change, hyperplasia would have been the more likely interpretation instead of adenoma, as the diameter of the proliferating foci was less than three seminiferous tubules [

44]. It is also worth noting that testicular interstitial cells are prominent in marsupials, particularly in American marsupial families (and Australian bandicoots), where the proportion of testicular volume occupied by the interstitial cells can reach up to 20%, known as a type 3 organization [

45]. Although most Australian marsupials are documented to have a type 2 organization, occupying about 5% of testicular volume [

45], some dasyurids such as Antechinus artuartii are known to have two separate interstitial cell populations, one forming peritubular clusters thought to correspond to renewed cells in adulthood [

46]. It is unknown if this characteristic is shared by all dasyurid males [

47], but once again, such peritubular clustering could have mimicked hyperplasia. Although the functional significance and phylogenetic connotations of such changes are not unknown, familiarity of the anatomic pathologist with such anatomical variations is of utmost importance to perform adequate histological examinations in non-conventional species.

Prostatitis has been reported in sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps) and Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana) mostly associated with urinary tract infection resulting in hematuria, constipation and local pain, none of which were observed in this study perhaps due to the mild nature of the inflammation observed in dunnart 11 [

31,

38]. Venerally-transmitted, cytomegalovirus-associated prostatitis has been reported in other Australian dasyurids, the brush-tailed phascogale (Phascogale tapoatafa), the brown antechinus (Antechinus stuartii), and the dusky antechinus (A. swainsonii; [

48,

49]). As with other cytomegaloviruses, lesions were most frequent during stressful periods. If the inflammation observed in dunnart 11 was virally-induced, it is unlikely that viable virions would still be observable in the tissue due to chronicity. Nonetheless, future studies should consider a potential cytomegalovirus infection in dasyurid cases showing prostatic compromise. Prostatic mineralization is considered a senile change lacking clinical significance.

Cutaneous lymphoma was frequent in male dunnarts. There were two females in which both gross and histopathology findings could support a putative diagnosis of lymphoma; however, this diagnosis could not be confirmed due to the severe artefact present in the tissue impeding confirmatory testing. Thus, we will only discuss cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma in the male cohort. Dunnarts with cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphomas presented with extensive alopecia with crusting and ulcerative lesions in the skin. Interestingly, lesions were remarkably similar in distribution and severity, which could indicate a viral etiology. Oncogenic viruses, specifically those of the retroviral lineage, such as the Koala Retrovirus and Gunnison’s Prairie Dog Retrovirus are associated with lymphoid neoplasia in wildlife in Australia and elsewhere [

50,

51]. This hypothesis might be worth exploring in future studies. Cutaneous epitheliotropic T-cell lymphoma (ETL) is primarily a disease of aged animals and has been reported in a variety of marsupials [

52,

53] and dasyurids, including Tasmanian devils [

54]. In dogs, lesions develop from a patch displaying significant epitheliotropism into a tumour stage with metastasis in as little time as 5.5 months [

55] with cutaneous forms (as the dunnarts in this study) considered independent predictors of poor survival compared to mucocutaneous/mucosal forms [

56]. The ETL disease spectrum is divided into mycosis fungoides (MF; most common form, strong tropism for epidermis and adnexa), pagetoid reticulosis (MF with lymphadenopathy and circulating neoplastic lymphocytes) and Sézary syndrome (solitary plaque; [

57]). According to this classification, the three ETL cases in this study correspond to MF due to the presence of: 1) intraepidermal vesicles containing pleomorphic neoplastic lymphocytes (Pautrier’s microabscesses), 2) infiltration of follicles and adnexa (epitheliotropism), 3) pleomorphic infiltrate predominantly comprised of lymphocytes with occasional histiocytes and granulocytes. Predisposing factors to cutaneous ETL are not known, however, chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation, as it occurs in atopic dermatitis cases, is noted as a risk factor for dogs [

58]. It remains to be determined if chronic dermatitis, as diagnosed in one male excluded from the study, predisposes aged dunnarts to cutaneous ETL. Although speculative, another possible risk factor for dunnart lymphoma occurrence is the male sex, as indicated by previous studies in neutered dogs, and humans [

59,

60] suggesting an endocrine dysregulation component. Interestingly and perhaps unsurprisingly, 2 of the 3 dunnarts with ETL also had concurrent testicular degeneration, which would lead to low circulating testosterone levels and subsequently, supraphysiologic luteinizing hormone (LH) levels due to the absence of negative feedback to the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary axis as would happen in gonadectomized animals. LH has receptors in reproductive and non-reproductive tissues such as lymphocytes and lymphoid tissue (thymic medulla); the function of these receptors is still not fully understood but appears to relate to induction of cell function and division [

61], the latter, via an ERK-dependent pathway [

62]. High LH would lead to a constant activation and magnification of LH effects in non-reproductive tissues, including T lymphocytes [

63]. LH-receptor positive T lymphocytes have been shown to circulate in higher numbers in gonadectomized dogs compared to intact individuals [

64] plausibly stimulating cell division through T-lymphocyte bound LH receptor activation. These findings correspond to outcomes of in vitro experiments and thus, prospective case-control trials are required to further verify a causative association [

63,

65]. Nonetheless, if dunnarts with testicular degeneration have comparable endocrine profiles to gonadectomized dogs, it could potentially lead to similar pathophysiological effects of sustained supraphysiologic LH levels. It is also unknown, however, if the onset of testicular degeneration in the male dunnarts included in this study occurred earlier or later in life. We speculate testicular degeneration is likely to be a consequence of aging, as its occurrence in younger or pre-pubertal dunnarts would likely have led to other significant health issues, due to the loss of negative feedback to the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary. In dogs and humans, sustained supraphysiologic levels of LH have been documented to lead to metabolic (hypothyroidism), musculoskeletal issues (increased ligament laxity) or urinary issues (incontinence); [

63,

65]. Lesions compatible with these health issues were not observed in the dunnarts included in this study.

The insufficient leukocytic marker immunolabeling observed in nodal control tissue hampered our ability to utilise IHC to definitively immunophenotype the cutaneous lymphomas observed. Possible issues that could have negatively impacted IHC immunolabeling quality include poor preservation of sample prior to freezing, age of samples (nearly a decade old), preservation artefact (freezing), lack of proper validation procedures in the species, and prolonged or variable formalin fixation time between samples [

66]. Pan-cytokeratin did provide adequate diagnostic immunolabeling in control tissue facing the same preservation and fixation challenges. However, being pan-cytokeratin a different epitope, it is unlikely to be equally negatively influenced by the aforementioned challenges that did affect leukocytic and hematopoietic markers.

Hair loss has been extensively documented in captive wildlife and can be caused by stress, excessive grooming, parasites, integument diseases, dietary deficiencies, and infections (fungal and bacterial) amongst others. The alopecia observed could have some similarity with telogen effluvium, a well-described condition in domestic animals in which there is pelage loss associated with extrinsic physical, physiological, or mental stressors or improper diets. With telogen effluvium, there is excessive generalised hair shedding with reduction in hair volume that does not render complete baldness. The pattern of alopecia observed in the three males affected were similar to what has been reported in macaques [

67] and bats [

68] where stress has been detected as an important cause. Further, comedone formation, although infrequently observed, could support underlying stress or endocrinopathies as it has been documented in small animals [

69].

Barbering – the act of plucking whiskers and fur in mice due to excessive grooming – would be an important differential diagnosis in these cases if it is confirmed that captive dunnarts can replicate such behaviour responding to social dominance [

70]. Excessive hair pulling (trichotillomania) is different and has also been observed in macaques and can be partially corrected with environmental enrichment [

71]. Despite whiskers being intact in this study, males were overrepresented with alopecia which may grant the exploration of hierarchical conflicts with females as a cause, as female mice are more likely to apply this behavior than males. As chronic stress is a well-recognized issue in captive wildlife and has been found to be associated with conditions observed in this study, future attempts at establishing captive breeding dunnart colonies could benefit from exploring environmental enrichment as well as the incorporation of non-invasive fecal glucocorticoid metabolite testing or hair cortisol levels as biomarkers to monitor stress levels [

72].

Senescence is a risk factor for cancer development. Both mature age and cancer share disease mechanisms such as genomic instability, epigenetic changes, altered nutrient sensing metabolism and are fundamentally divergent in others, such as telomere attrition in geriatric cells in contrast to the ability to perform rapid cell division and high energy consumption of neoplastic cells [

73]. The lifespan of captive Julia Creek dunnarts was increased by approximately one year and so the molecular mechanisms associated with aging are suggested as the underlying mechanisms for the interconnectedness of aging and neoplasia observed in this study. Nonetheless, future studies should aim at investigating other potential etiologies including oncogenic viruses.

Reproductive aging is a crucial phenomenon of concern in any conservation breeding program, particularly for genetically valuable wildlife as research has shown long-term captivity can lead to prolonged exposure to endogenous sex steroids and long non-reproductive intervals resulting in asymmetric reproductive aging and low reproductive performance [

74]. In asymmetric reproductive aging, females in which first breeding attempts and pregnancies are substantially delayed result in frequent cyclic fluctuations of estrogen subsequently causing reproductive disease as tested in cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) [

75]. The theory is interesting and could be applied to dasyurids although its veracity remains to be tested. To avoid asymmetric reproductive aging, reduced fertility and irreversible acyclicity especially in short-lived wildlife, captive breeding programs can benefit from incorporating basic cytological assessment of reproductive cycle phases (e.g. urogenital/vaginal mucus or urine smears [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80] to monitor fertility and perform early and regular selective breeding of young and genetically valued females. Alternatively, captive breeding programs could benefit from the use of pioneered assisted reproductive technologies to induce pregnancies as early as possible [

74,

81,

82], or monitoring for behavioural signals (e.g. wheel running activity, [

83]).

Figure 1.

Gross Female Reproductive Lesions in geriatric Julia Creek dunnarts. a) Cystic glandular hyperplasia (CGH), dunnart 14. A 2.5 cm diameter, pale pink to tan, firm abdominal cyst filled by a pale tan fluid is expanding the cavity and displacing abdominal viscera. b) CGH, dunnart 11. The right uterus measures 3.5 cm in diameter, is diffusely dark purple, firm and is found expanding the abdominal cavity displacing and compressing the abdominal viscera cranially as well as compressing the thoracic cavity causing pulmonary collapse. The uterine mass is filled with approx. 5 mL of dark red, inspissated fluid. c) CGH and endometrial papillary adenoma, dunnart 13. Rarely, a single uterus was expanded by two separate masses; the largest mass measures 2.5 cm diameter (arrowhead) and corresponds to CEH. The second mass (asterisk) is an endometrial papillary adenoma, measuring about 2 cm diameter and filled by viscous dark brown-orange material. d) Ovarian cyst, Not Otherwise Specified - NOS, dunnart 6. The ovary appears to be expanded by a single, unilocular mass filled by light yellow-pink fluid; bilaterally the uteri are appreciated below the mass. Photo credit: Peter Moore. e) Vaginal neutrophilic infiltrates, dunnart 10. Grossly, the lateral vaginas (arrowhead) were discolored off-white and moderately expanded, possibly indicating underlying pathologic inflammation. However, physiologic neutrophilic infiltrates that occur in certain small mammal species during metestrus and diestrus cannot fully be ruled out. This dunnart also had CGH and a cystic oviduct (not on image).

Figure 1.

Gross Female Reproductive Lesions in geriatric Julia Creek dunnarts. a) Cystic glandular hyperplasia (CGH), dunnart 14. A 2.5 cm diameter, pale pink to tan, firm abdominal cyst filled by a pale tan fluid is expanding the cavity and displacing abdominal viscera. b) CGH, dunnart 11. The right uterus measures 3.5 cm in diameter, is diffusely dark purple, firm and is found expanding the abdominal cavity displacing and compressing the abdominal viscera cranially as well as compressing the thoracic cavity causing pulmonary collapse. The uterine mass is filled with approx. 5 mL of dark red, inspissated fluid. c) CGH and endometrial papillary adenoma, dunnart 13. Rarely, a single uterus was expanded by two separate masses; the largest mass measures 2.5 cm diameter (arrowhead) and corresponds to CEH. The second mass (asterisk) is an endometrial papillary adenoma, measuring about 2 cm diameter and filled by viscous dark brown-orange material. d) Ovarian cyst, Not Otherwise Specified - NOS, dunnart 6. The ovary appears to be expanded by a single, unilocular mass filled by light yellow-pink fluid; bilaterally the uteri are appreciated below the mass. Photo credit: Peter Moore. e) Vaginal neutrophilic infiltrates, dunnart 10. Grossly, the lateral vaginas (arrowhead) were discolored off-white and moderately expanded, possibly indicating underlying pathologic inflammation. However, physiologic neutrophilic infiltrates that occur in certain small mammal species during metestrus and diestrus cannot fully be ruled out. This dunnart also had CGH and a cystic oviduct (not on image).

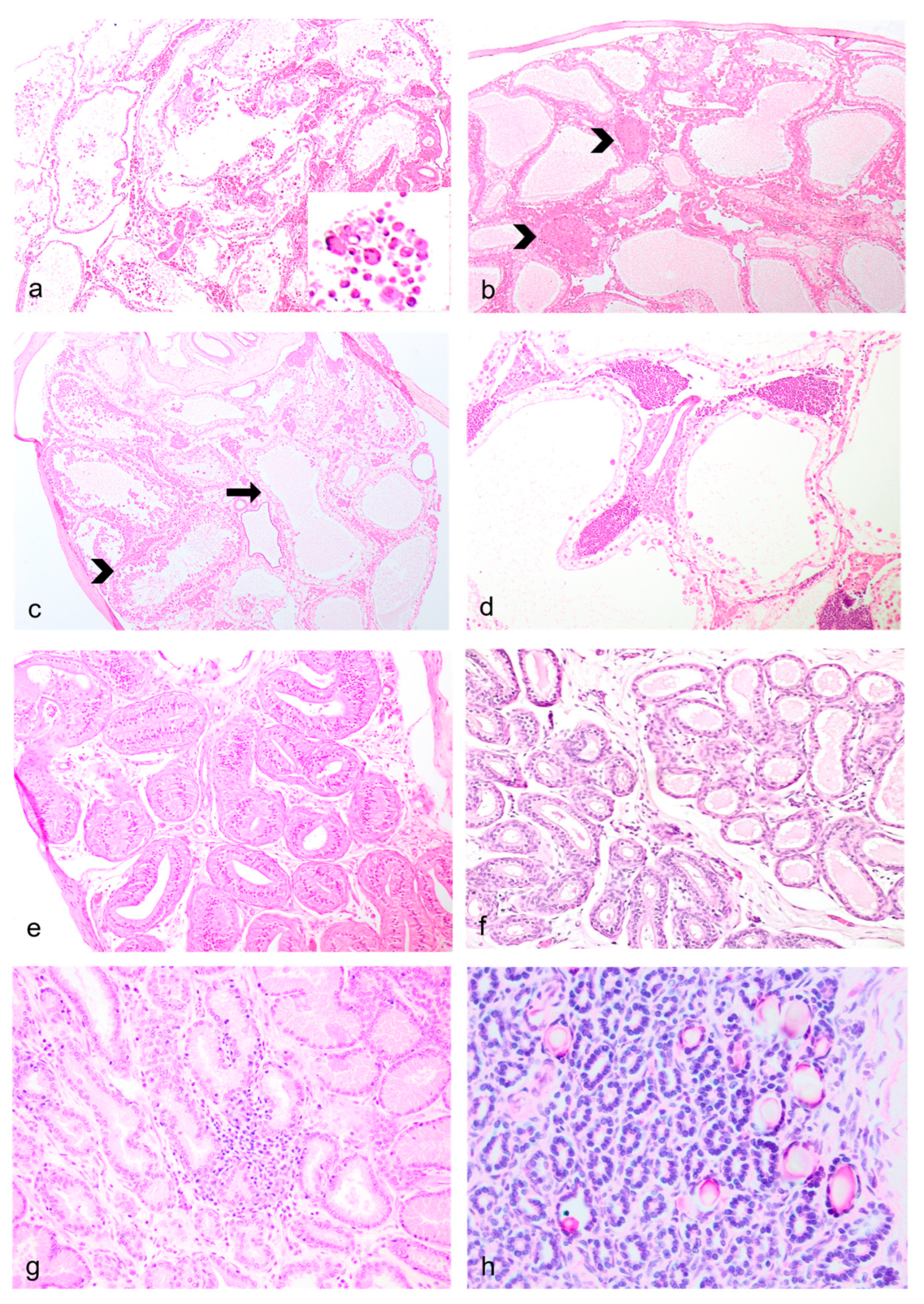

Figure 2.

Female Reproductive Lesions in Geriatric Julia Creek Dunnarts. a) Age-related ovarian atrophy, dunnart 8. Low numbers of primordial or primary follicles, few secondary follicles and 2 corpora albicans are observed. No corpora lutea are present, potentially indicating acyclic state. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, 10X. b) Cystic oviduct, dunnart 9. The proximal end of the oviduct (ampulla or isthmus region) is expanded by a single, 5-7 mm diameter, fluid filled cyst lined by a single layer of ciliated attenuated columnar epithelium, H&E stain, 40X. c) Cystic glandular hyperplasia (CGH), dunnart 3. Subgross view of the uterine wall with diffusely, actively proliferating, tortuous, dilated, and often cystic endometrial glands. Hyperplastic glands lie back-to-back supported by stromal bands of variably width and segmentally contain papillae covered by columnar, stratified to pseudostratified epithelium. H&E stain, 4X. d) CGH with mucin, dunnart 7. High magnification view into one of the cystic structures found expanding the endometrium formed by anastomosing trabeculae of thin fibrous connective tissue septa lined by a single line of ciliated columnar secretory epithelium, with abundant goblet cells, H&E stain, 20X. e) CGH with squamous metaplasia, dunnart 11. The endometrium is expanded by numerous islands and anastomosing trabeculae forming cysts filled by fluid and necrotic debris lined by tall columnar cells. Foci of metaplastic, stratified, squamous, non-keratizining epithelium are observed (asterisk). H&E stain, 20X. f) Endometrial (glandular) polyp, dunnart 14. A polypoid mass protrudes into the uterine lumen comprised of numerous glands lined by predominantly hyperplastic/dysplastic columnar glandular epithelium, mimicking endometrial mucosa, and supported by a stroma comprised of spindle cells with variable amounts of collagen and scattered small-caliber vasculature. Focal squamous metaplasia (asterisk) is also observed. H&E stain, 4X. g-h) Endometrial adenoma, papillary, with focal squamous metaplasia, dunnart 13. A neoplastic mass supported by a broad-base formed by well-differentiated columnar, pseudostratified, mucus secreting epithelial cells arranged in a papillary pattern (Figure F) mimicking endometrial epithelium is observed replacing the uterine stroma. No invasion to the endometrium or myometrium is observed. Focal squamous stratified and pseudostratified non-keratinising epithelium is also observed forming fronds, covered by large amounts of necrotic debris. H&E stain, 20X. i) Vaginal neutrophilic infiltrates, dunnart 10. Florid neutrophilic infiltrates are observed multifocally exocytosing into the vagina mucosa and infiltrating the lamina propria, possibly supporting a pathologic vaginitis over those granulocytic infiltrates of physiological origin that infiltrate during metestrus or diestrus. H&E stain, 10X.

Figure 2.

Female Reproductive Lesions in Geriatric Julia Creek Dunnarts. a) Age-related ovarian atrophy, dunnart 8. Low numbers of primordial or primary follicles, few secondary follicles and 2 corpora albicans are observed. No corpora lutea are present, potentially indicating acyclic state. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, 10X. b) Cystic oviduct, dunnart 9. The proximal end of the oviduct (ampulla or isthmus region) is expanded by a single, 5-7 mm diameter, fluid filled cyst lined by a single layer of ciliated attenuated columnar epithelium, H&E stain, 40X. c) Cystic glandular hyperplasia (CGH), dunnart 3. Subgross view of the uterine wall with diffusely, actively proliferating, tortuous, dilated, and often cystic endometrial glands. Hyperplastic glands lie back-to-back supported by stromal bands of variably width and segmentally contain papillae covered by columnar, stratified to pseudostratified epithelium. H&E stain, 4X. d) CGH with mucin, dunnart 7. High magnification view into one of the cystic structures found expanding the endometrium formed by anastomosing trabeculae of thin fibrous connective tissue septa lined by a single line of ciliated columnar secretory epithelium, with abundant goblet cells, H&E stain, 20X. e) CGH with squamous metaplasia, dunnart 11. The endometrium is expanded by numerous islands and anastomosing trabeculae forming cysts filled by fluid and necrotic debris lined by tall columnar cells. Foci of metaplastic, stratified, squamous, non-keratizining epithelium are observed (asterisk). H&E stain, 20X. f) Endometrial (glandular) polyp, dunnart 14. A polypoid mass protrudes into the uterine lumen comprised of numerous glands lined by predominantly hyperplastic/dysplastic columnar glandular epithelium, mimicking endometrial mucosa, and supported by a stroma comprised of spindle cells with variable amounts of collagen and scattered small-caliber vasculature. Focal squamous metaplasia (asterisk) is also observed. H&E stain, 4X. g-h) Endometrial adenoma, papillary, with focal squamous metaplasia, dunnart 13. A neoplastic mass supported by a broad-base formed by well-differentiated columnar, pseudostratified, mucus secreting epithelial cells arranged in a papillary pattern (Figure F) mimicking endometrial epithelium is observed replacing the uterine stroma. No invasion to the endometrium or myometrium is observed. Focal squamous stratified and pseudostratified non-keratinising epithelium is also observed forming fronds, covered by large amounts of necrotic debris. H&E stain, 20X. i) Vaginal neutrophilic infiltrates, dunnart 10. Florid neutrophilic infiltrates are observed multifocally exocytosing into the vagina mucosa and infiltrating the lamina propria, possibly supporting a pathologic vaginitis over those granulocytic infiltrates of physiological origin that infiltrate during metestrus or diestrus. H&E stain, 10X.

Figure 3.

Gross Male Reproductive and Non-reproductive Lesions in Geriatric Julia Creek Dunnarts. a) Testicular degeneration/atrophy, dunnart 9. The scrotal sac has a markedly shortened inguinal canal turning it into a sessile structure with no obvious palpable testes, easily exposing the urogenital sinus (arrowhead) and bulbourethral glands (asterisks). b) Normal testes and scrotum, control dunnart. Scrotum contains palpable testes and is suspended from the abdomen by a regular stalk with the inguinal canal containing the spermatic cord, completely covering the urogenital sinus and partially the bulbourethral glands. c) Bilateral testicular degeneration/atrophy, dunnart 4. The left testicle (arrowhead) is around 1.5 times smaller in globally larger right testicle, indicating a unilateral testicular tubular degeneration/atrophy in this dunnart. d-e) Cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma, dunnart 4. Extensive areas of alopecia affecting 90% of the body with diffusely markedly thickened skin that is mottled pink, red and with multiple scabs and flaking in the caudo-dorsal region. The coat is maintained in the distal cervical and proximal dorsal and flank region. f) Dermatitis with alopecia, dunnart not included in study included for comparison. An approx. 2 cm band of circumferential alopecia is observed in the cranial abdomen. Follicular atrophy was noticed on histopathology. Note the skin is smooth, not crusty, ulcerated nor thickened as in the epitheliotropic lymphoma cases. g) Telogen alopecia, dunnart 25. Lateral view. Regionally extensive areas of alopecia are observed predominantly affecting the lateral thighs and rump region in this view. The skin appears thickened and focally wrinkly. h) Telogen alopecia, dunnart 25. Dorsal view. About 50% of the body presents a bilaterally symmetrical alopecia, particularly focused in the head, lateral thighs and rump region. i) Telogen alopecia, dunnart 31. There is bilaterally symmetrical alopecia affecting the lateral thighs, rump and cranio-dorsal abdominal region. Inset: Alopecia was occasionally observed along comedone formation. The right pinna has been removed post-mortem from all dunnarts in the photographs for DNA analysis.

Figure 3.

Gross Male Reproductive and Non-reproductive Lesions in Geriatric Julia Creek Dunnarts. a) Testicular degeneration/atrophy, dunnart 9. The scrotal sac has a markedly shortened inguinal canal turning it into a sessile structure with no obvious palpable testes, easily exposing the urogenital sinus (arrowhead) and bulbourethral glands (asterisks). b) Normal testes and scrotum, control dunnart. Scrotum contains palpable testes and is suspended from the abdomen by a regular stalk with the inguinal canal containing the spermatic cord, completely covering the urogenital sinus and partially the bulbourethral glands. c) Bilateral testicular degeneration/atrophy, dunnart 4. The left testicle (arrowhead) is around 1.5 times smaller in globally larger right testicle, indicating a unilateral testicular tubular degeneration/atrophy in this dunnart. d-e) Cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma, dunnart 4. Extensive areas of alopecia affecting 90% of the body with diffusely markedly thickened skin that is mottled pink, red and with multiple scabs and flaking in the caudo-dorsal region. The coat is maintained in the distal cervical and proximal dorsal and flank region. f) Dermatitis with alopecia, dunnart not included in study included for comparison. An approx. 2 cm band of circumferential alopecia is observed in the cranial abdomen. Follicular atrophy was noticed on histopathology. Note the skin is smooth, not crusty, ulcerated nor thickened as in the epitheliotropic lymphoma cases. g) Telogen alopecia, dunnart 25. Lateral view. Regionally extensive areas of alopecia are observed predominantly affecting the lateral thighs and rump region in this view. The skin appears thickened and focally wrinkly. h) Telogen alopecia, dunnart 25. Dorsal view. About 50% of the body presents a bilaterally symmetrical alopecia, particularly focused in the head, lateral thighs and rump region. i) Telogen alopecia, dunnart 31. There is bilaterally symmetrical alopecia affecting the lateral thighs, rump and cranio-dorsal abdominal region. Inset: Alopecia was occasionally observed along comedone formation. The right pinna has been removed post-mortem from all dunnarts in the photographs for DNA analysis.

Figure 4.

Male Reproductive Lesions in Geriatric Julia Creek dunnarts. a) Testicular diffuse testicular tubular degeneration/atrophy with azoospermia, left testis, dunnart 4. Despite autolytic artefact which has removed the germinal epithelium and Sertolli cells from the seminiferous tubular lining, there are multiple, rounded, variably sized-cells that are observed floating within the tubular lumina. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, 4X. Inset: Small aggregates of large, rounded multiple germ cell nuclei of similar maturity are observed within degenerated seminiferous tubular lumina, interpreted as multinucleated giant cells of germ cell origin. b) Testicular degeneration with azoospermia, right testis, dunnart 4. The seminiferous tubules are devoid of early and late spermatids; no spermatogenesis is observed. Supporting basement membrane is wavy, buckled and thickened. Few granulomas are observed replacing seminiferous tubules (arrowheads), likely resulting from tubular shrinkage and collapse and/or spermiostasis. Numerous peritubular interstitial (Leydig) cells aggregates are observed forming non-compressive clusters, likely enhanced by the disappearing tubules. Increased numbers of interstitial cells are a normal finding in multiple marsupial species. H&E stain, 4X. c) Segmental tubular degeneration/atrophy, dunnart 4. Degeneration/atrophy also affected segments of seminiferous tubules, resulting in the visualization of tubules still containing germ cells in various stages of maturation (arrowhead) abutting others virtually devoid of germ cell epithelium but with a few remaining Sertolli cells (arrow). H&E stain, 4X. d) Metastatic testicular lymphoma, dunnart 5. The interstitium is unilaterally expanded by dense aggregates of lymphocytes, mainly within vasculature. H&E stain, 10X. e) Epididymal segmental ductal atrophy, dunnart 5. Segmental narrowing of the ductal lumina is observed with normal appearing epithelium, along occasionally lower epithelial height, likely due to testicular degeneration/atrophy in ipsilateral testis. H&E stain, 10X. f) Severe bilateral testicular atrophy, dunnart 8. No identifiable testicular tissue was found within the scrotum, only a portion of the epididymis. Some of these tubules contain protein however epithelium is attenuated and no sperm is visualized. H&E stain, 20X. g) Prostatitis, dunnart 12. The interstitium is multifocally expanded by small aggregates of lymphocytes and occasional plasma cells. H&E stain, 20X. h) Calcified prostatic concretions, dunnart 9. Multifocally within glandular lumina are variably-sized, irregularly-shaped mineral deposits. H&E stain, 40X.

Figure 4.

Male Reproductive Lesions in Geriatric Julia Creek dunnarts. a) Testicular diffuse testicular tubular degeneration/atrophy with azoospermia, left testis, dunnart 4. Despite autolytic artefact which has removed the germinal epithelium and Sertolli cells from the seminiferous tubular lining, there are multiple, rounded, variably sized-cells that are observed floating within the tubular lumina. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, 4X. Inset: Small aggregates of large, rounded multiple germ cell nuclei of similar maturity are observed within degenerated seminiferous tubular lumina, interpreted as multinucleated giant cells of germ cell origin. b) Testicular degeneration with azoospermia, right testis, dunnart 4. The seminiferous tubules are devoid of early and late spermatids; no spermatogenesis is observed. Supporting basement membrane is wavy, buckled and thickened. Few granulomas are observed replacing seminiferous tubules (arrowheads), likely resulting from tubular shrinkage and collapse and/or spermiostasis. Numerous peritubular interstitial (Leydig) cells aggregates are observed forming non-compressive clusters, likely enhanced by the disappearing tubules. Increased numbers of interstitial cells are a normal finding in multiple marsupial species. H&E stain, 4X. c) Segmental tubular degeneration/atrophy, dunnart 4. Degeneration/atrophy also affected segments of seminiferous tubules, resulting in the visualization of tubules still containing germ cells in various stages of maturation (arrowhead) abutting others virtually devoid of germ cell epithelium but with a few remaining Sertolli cells (arrow). H&E stain, 4X. d) Metastatic testicular lymphoma, dunnart 5. The interstitium is unilaterally expanded by dense aggregates of lymphocytes, mainly within vasculature. H&E stain, 10X. e) Epididymal segmental ductal atrophy, dunnart 5. Segmental narrowing of the ductal lumina is observed with normal appearing epithelium, along occasionally lower epithelial height, likely due to testicular degeneration/atrophy in ipsilateral testis. H&E stain, 10X. f) Severe bilateral testicular atrophy, dunnart 8. No identifiable testicular tissue was found within the scrotum, only a portion of the epididymis. Some of these tubules contain protein however epithelium is attenuated and no sperm is visualized. H&E stain, 20X. g) Prostatitis, dunnart 12. The interstitium is multifocally expanded by small aggregates of lymphocytes and occasional plasma cells. H&E stain, 20X. h) Calcified prostatic concretions, dunnart 9. Multifocally within glandular lumina are variably-sized, irregularly-shaped mineral deposits. H&E stain, 40X.

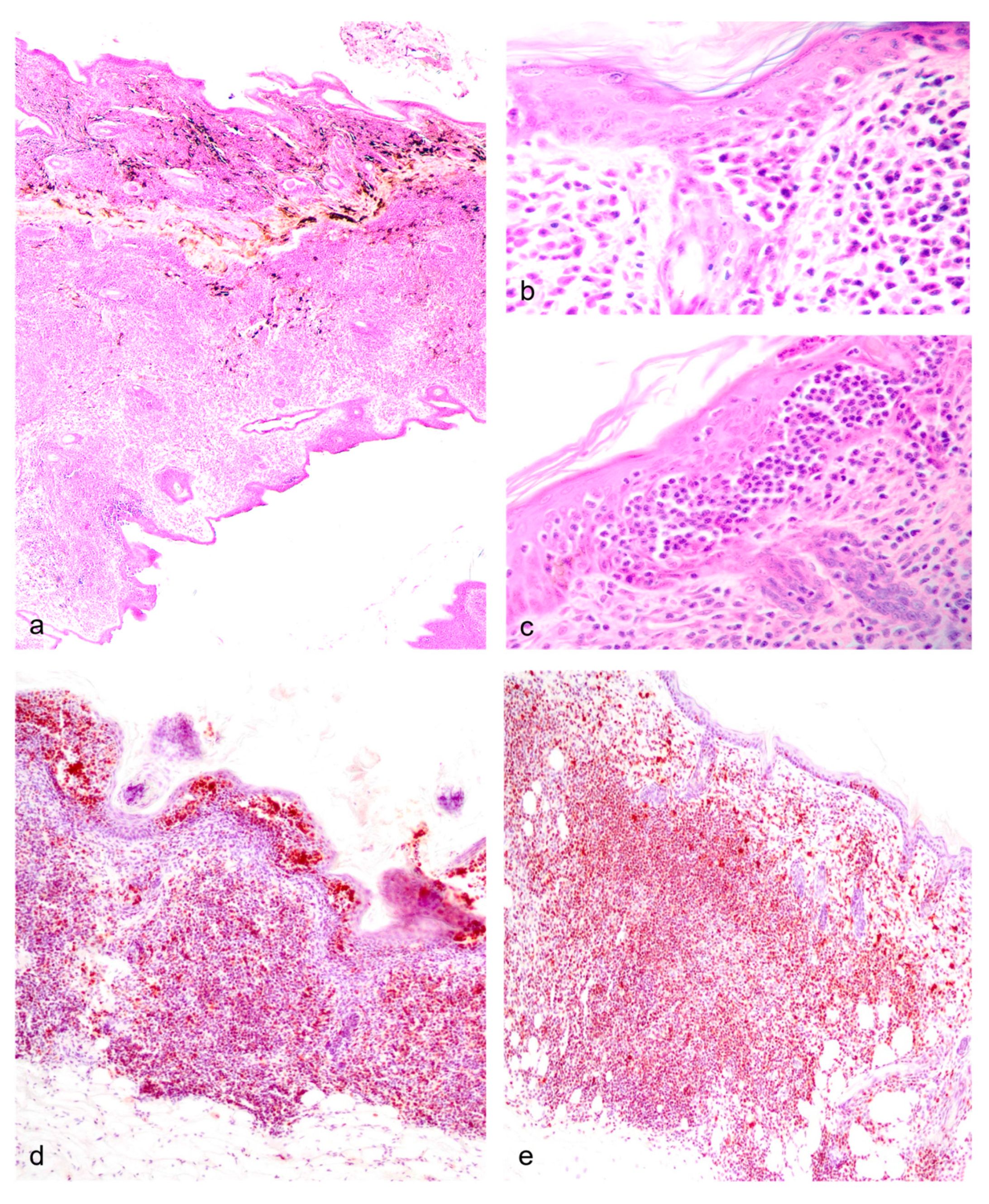

Figure 5.

Non-Reproductive Lesions of Geriatric Male Julia Creek Dunnarts. a) Primary cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), dunnart 5. The dermis is infiltrated and replaced by a non-encapsulated and densely cellular neoplasm arranged in sheets. In multiple areas, the subcutis is also infiltrated. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, 4X. b) Primary cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), dunnart 4. Dermal infiltrate is predominantly comprised of lymphocytes with hyperchromatic, convoluted or cerebriform nuclei admixed with occasional histiocytes and granulocytes. Multifocally, hair follicles are effaced by the infiltration of low numbers of neoplastic cells within the outer root sheath. H&E, 40X. c) Primary cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), dunnart 5. Multiple intraepidermal vesicles are filled with pleomorphic lymphoid cells (Pautrier’s microabscesses) and occasionally by solitary cells surrounded by a clear halo. H&E, 40X. d) Peripheral diffuse cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma, dunnart 1. Sheets of neoplastic lymphocytes are observed expanding the dermis, displacing adnexa and infiltrating and expanding the epidermis forming discrete and often coalescing Pautrier’s microabscesses. CD3 immunohistochemistry – IHC, 20X. e) Peripheral diffuse cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma, dunnart 1. Neoplastic lymphocytes also reached into and isolated adipocytes. CD3 IHC, 10X.

Figure 5.

Non-Reproductive Lesions of Geriatric Male Julia Creek Dunnarts. a) Primary cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), dunnart 5. The dermis is infiltrated and replaced by a non-encapsulated and densely cellular neoplasm arranged in sheets. In multiple areas, the subcutis is also infiltrated. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, 4X. b) Primary cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), dunnart 4. Dermal infiltrate is predominantly comprised of lymphocytes with hyperchromatic, convoluted or cerebriform nuclei admixed with occasional histiocytes and granulocytes. Multifocally, hair follicles are effaced by the infiltration of low numbers of neoplastic cells within the outer root sheath. H&E, 40X. c) Primary cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), dunnart 5. Multiple intraepidermal vesicles are filled with pleomorphic lymphoid cells (Pautrier’s microabscesses) and occasionally by solitary cells surrounded by a clear halo. H&E, 40X. d) Peripheral diffuse cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma, dunnart 1. Sheets of neoplastic lymphocytes are observed expanding the dermis, displacing adnexa and infiltrating and expanding the epidermis forming discrete and often coalescing Pautrier’s microabscesses. CD3 immunohistochemistry – IHC, 20X. e) Peripheral diffuse cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma, dunnart 1. Neoplastic lymphocytes also reached into and isolated adipocytes. CD3 IHC, 10X.

Table 1.

Female reproductive and non-reproductive tract lesions in endangered geriatric Julia Creek dunnarts from a captive breeding colony.

Table 1.

Female reproductive and non-reproductive tract lesions in endangered geriatric Julia Creek dunnarts from a captive breeding colony.

| Diagnoses |

Dunnart ID |

Age (months) |

| Ovaries |

|

|

| Cystic ovary (possibly bursal) |

6 |

25 |

| Age-related ovarian atrophy |

8 |

25 |

| Age-related ovarian atrophy |

10 |

42 |

| Oviduct |

|

|

| Cystic oviduct |

10 |

42 |

| Uterus |

|

|

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia |

3 |

27 |

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia/dysplasia, squamous metaplasia |

7 |

25 |

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia with mucin |

8 |

25 |

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia |

2 |

24 |

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia |

10 |

42 |

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia |

24 |

24 |

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia, polyp (glandular) |

27 |

24 |

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia |

11 |

20 |

| Cystic glandular hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, polyp (glandular) |

14 |

42 |

| Endometrial polyp (glandular) |

23 |

12 |

| Endometrial polyp (glandular), cystic |

30 |

24 |

| Endometrial polyp (glandular), cystic |

32 |

24 |

| Endometrial adenoma, papillary, focal squamous metaplasia |

13 |

42 |

| Cervix and vagina |

|

|

| Neutrophilic infiltrates in cervix and vagina with fibrosis |

8 |

25 |

| Neutrophilic infiltrates in vagina |

10 |

42 |

| Skin |

|

|

| Round cell infiltrates, superficial dermis, non-epitheliotropic |

30 |

24 |

| Round cell infiltrates, mid-to-deep dermal, epitheliotropic |

33 |

12 |

Table 2.

Male reproductive and non-reproductive tract lesions in endangered geriatric Julia Creek dunnarts from a captive breeding colony.

Table 2.

Male reproductive and non-reproductive tract lesions in endangered geriatric Julia Creek dunnarts from a captive breeding colony.

| Diagnoses |

Dunnart ID |

Age (months) |

| Testes |

|

|

| Testicular tubular degeneration/atrophy with aspermatogenesis |

4 |

42 |

| Testicular tubular degeneration/atrophy with aspermatogenesis and metastatic lymphoma |

5 |

42 |

| Testicular tubular degeneration/atrophy |

9 |

42 |

| Prostate |

|

|

| Prostatic mineralization, multifocal |

9 |

42 |

| Lymphoplasmacytic prostatitis |

12 |

42 |

| Skin |

|

|

| Cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides) |

1 |

24 |

| Cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), with splenic and pulmonary metastasis |

4 |

42 |

| Cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), with splenic, pulmonary, and testicular metastasis |

5 |

42 |

| Cutaneous round cell infiltrates, telogen alopecia |

25 |

48 |

| Cutaneous round cell infiltrates |

31 |

48 |

| Telogen alopecia, hyperkeratosis |

20 |

36 |

| Telogen alopecia |

28 |

24 |

| Telogen alopecia |

29 |

24 |